| Psychosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Psychotic break |

| |

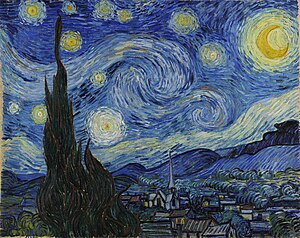

| Van Gogh's The Starry Night, from 1889, shows changes in light and color as can appear with psychosis. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, psychology |

| Symptoms | False beliefs, seeing or hearing things that others do not see or hear, incoherent speech |

| Complications | Self-harm, suicide |

| Causes | Mental illness (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), sleep deprivation, some medical conditions, certain medications, drugs (including alcohol and cannabis) |

| Treatment | Antipsychotics, counselling, social support |

| Prognosis | Depends on cause |

| Frequency | 3% of people at some point in time (US) |

Psychosis is an abnormal condition of the mind that results in difficulties determining what is real and what is not. Symptoms may include false beliefs (delusions) and seeing or hearing things that others do not see or hear (hallucinations). Other symptoms may include incoherent speech and behavior that is inappropriate for the situation. There may also be sleep problems, social withdrawal, lack of motivation, and difficulties carrying out daily activities.

Psychosis has many different causes. These include mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, sleep deprivation, some medical conditions, certain medications, and drugs such as alcohol or cannabis. One type, known as postpartum psychosis, can occur after giving birth. The neurotransmitter dopamine is believed to play a role. Acute psychosis is considered primary if it results from a psychiatric condition and secondary if it is caused by a medical condition. The diagnosis of a mental illness requires excluding other potential causes. Testing may be done to check for central nervous system diseases, toxins, or other health problems as a cause.

Treatment may include antipsychotic medication, counselling, and social support. Early treatment appears to improve outcomes. Medications appear to have a moderate effect. Outcomes depend on the underlying cause. In the United States about 3% of people develop psychosis at some point in their lives. The condition has been described since at least the 4th century BCE by Hippocrates and possibly as early as 1,500 BCE in the Egyptian Ebers Papyrus.

Signs and symptoms

Hallucinations

A hallucination is defined as sensory perception in the absence of external stimuli. Hallucinations are different from illusions,

or perceptual distortions which are the misperception of external

stimuli. Hallucinations may occur in any of the senses and take on

almost any form, which may include simple sensations (such as lights,

colors, tastes, and smells) to experiences such as seeing and

interacting with fully formed animals and people, hearing voices, and

having complex tactile sensations. Hallucinations are generally

characterized as being vivid, and uncontrollable.

Auditory hallucinations,

particularly experiences of hearing voices, are the most common and

often prominent feature of psychosis.

Up to 15% of the general population may experience auditory

hallucinations. The prevalence in schizophrenia is generally put around

70%, but may go as high as 98%. During the early 20th century auditory

hallucinations were second to visual hallucinations in frequency, but

they are now the most common manifestation of schizophrenia, although

rates vary throughout cultures and regions. Auditory hallucinations are

most commonly intelligible voices. When voices are present, the

average number has been estimated at three. Content, like frequency,

differs significantly, especially across cultures and demographics.

People who experience auditory hallucinations can frequently identify

the loudness, location of origin, and may settle on identities for

voices. Western cultures are associated with auditory experiences

concerning religious content, frequently related to sin. Hallucinations

may command a person to do something which may be dangerous when

combined with delusions.

Extracampine hallucinations are auditory hallucinations

originating from a particular body part (e.g. a voice coming from a

person's knee).

Visual hallucinations occur in roughly a third of people with

schizophrenia, although rates as high as 55% are reported. Content

frequently involves animate objects, although perceptual abnormalities

such as changes in lighting, shading, streaks, or lines may be seen.

Visual abnormalities may conflict with proprioceptive information, and visions may include experiences such as the ground tilting. Lilliputian hallucinations are less common in schizophrenia, and occur more frequently in various types of encephalopathy (e.g. Peduncular hallucinosis).

A visceral hallucination, also called a cenesthetic

hallucination, is characterized by visceral sensations in the absence of

stimuli. Cenesthetic hallucinations may include sensations of burning,

or re-arrangement of internal organs.

Delusions

Psychosis may involve delusional

beliefs. Delusions are strong beliefs against reality or held despite

contradictory evidence. Delusions are necessarily incongruent with

societal norms, as some beliefs may constitute a delusion in certain

cultures where they impact functioning, while they may be a perfectly

normal belief in others. The distinguishing feature between delusional

thinking and full-blown delusions is the degree with which they impact

functioning. Multiple themes are common in delusions, although cultural

norms are highly influential (e.g. religious content differing

significantly across countries). The most common type of delusion is a persecutory delusion,

where a person believes that an individual, organization or group is

attempting to harm them. Other delusions include delusions of reference

(beliefs that a particular stimulus has a special meaning that is

directed at the holder of belief), grandiose delusions (delusions that a

person has a special power or importance), thought broadcasting (the

belief that one's thoughts are audible) and thought insertion (the

belief that one's thoughts are not one's own). The DSM-5 characterizes

certain delusions as "bizarre" if they are clearly implausible, or are

incompatible within the cultural context. The concept of bizarre

delusions has been criticized as excessively subjective.

Historically, Karl Jaspers has classified psychotic delusions into primary and secondary

types. Primary delusions are defined as arising suddenly and not being

comprehensible in terms of normal mental processes, whereas secondary

delusions are typically understood as being influenced by the person's

background or current situation (e.g., ethnicity; also religious,

superstitious, or political beliefs).

Disorganization

Disorganization

is split into disorganized speech or thinking, and grossly disorganized

motor behavior. Disorganized speech, also called formal thought

disorder, is disorganization of thinking that is inferred from speech.

Characteristics of disorganized speech include rapidly switching topics,

called derailment or loose association; switching to topics that are

unrelated, called tangential thinking; incomprehensible speech, called

word salad or incoherence. Disorganized motor behavior includes

repetitive, odd, or sometimes purposeless movement. Disorganized motor

behavior rarely includes catatonia, and although it was a historically

prominent symptom, it is rarely seen today. Whether this is due to

historically used treatments or the lack thereof is unknown.

Catatonia

describes a profoundly agitated state in which the experience of

reality is generally considered impaired. There are two primary

manifestations of catatonic behavior. The classic presentation is a

person who does not move or interact with the world in any way while

awake. This type of catatonia presents with waxy flexibility.

Waxy flexibility is when someone physically moves part of a catatonic

person's body and the person stays in the position even if it is bizarre

and otherwise nonfunctional (such as moving a person's arm straight up

in the air and the arm staying there).

The other type of catatonia is more of an outward presentation of

the profoundly agitated state described above. It involves excessive

and purposeless motor behaviour, as well as extreme mental preoccupation

that prevents an intact experience of reality. An example is someone

walking very fast in circles to the exclusion of anything else with a

level of mental preoccupation (meaning not focused on anything relevant

to the situation) that was not typical of the person prior to the

symptom onset. In both types of catatonia there is generally no

reaction to anything that happens outside of them. It is important to

distinguish catatonic agitation from severe bipolar mania, although

someone could have both.

Negative symptoms

Negative symptoms include reduced emotional expression, decreased motivation and reduced spontaneous speech. They lack interest and spontaneity, and have the inability to feel pleasure.

Causes

Normal states

Brief hallucinations are not uncommon in those without any psychiatric disease. Causes or triggers include:

- Falling asleep and waking: hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations, which are entirely normal

- Bereavement, in which hallucinations of a deceased loved one are common

- Severe sleep deprivation

Trauma

Traumatic life events have been linked with elevated risk in developing psychotic symptoms. Childhood trauma has specifically been shown to be a predictor of adolescent and adult psychosis.

Approximately 65% of individuals with psychotic symptoms have

experienced childhood trauma (e.g., physical or sexual abuse, physical

or emotional neglect).

Increased individual vulnerability toward psychosis may interact with

traumatic experiences promoting onset of future psychotic symptoms,

particularly during sensitive developmental periods.

Importantly, the relationship between traumatic life events and

psychotic symptoms appears to be dose-dependent in which multiple

traumatic life events accumulate, compounding symptom expression and

severity.

This suggests trauma prevention and early intervention may be an

important target for decreasing the incidence of psychotic disorders and

ameliorating its effects.

Psychiatric disorder

From

a diagnostic standpoint, organic disorders were believed to be caused

by physical illness affecting the brain (that is, psychiatric disorders

secondary to other conditions) while functional disorders were

considered disorders of the functioning of the mind in the absence of

physical disorders (that is, primary psychological or psychiatric

disorders). Subtle physical abnormalities have been found in illnesses

traditionally considered functional, such as schizophrenia. The DSM-IV-TR

avoids the functional/organic distinction, and instead lists

traditional psychotic illnesses, psychosis due to general medical

conditions, and substance-induced psychosis.

Primary psychiatric causes of psychosis include the following:

- schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder

- affective (mood) disorders, including major depression, and severe depression or mania in bipolar disorder (manic depression). People experiencing a psychotic episode in the context of depression may experience persecutory or self-blaming delusions or hallucinations, while people experiencing a psychotic episode in the context of mania may form grandiose delusions.

- schizoaffective disorder, involving symptoms of both schizophrenia and mood disorders

- brief psychotic disorder, or acute/transient psychotic disorder

- delusional disorder (persistent delusional disorder)

- chronic hallucinatory psychosis

Psychotic symptoms may also be seen in:

- schizotypal personality disorder

- certain personality disorders at times of stress (including paranoid personality disorder, schizoid personality disorder, and borderline personality disorder)

- major depressive disorder in its severe form, although it is possible and more likely to have severe depression without psychosis

- bipolar disorder in the manic and mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder and depressive episodes of both bipolar I and bipolar II; however, it is possible to experience such states without psychotic symptoms.

- post-traumatic stress disorder

- induced delusional disorder

- Sometimes in obsessive–compulsive disorder

- Dissociative disorders, due to many overlapping symptoms, careful differential diagnosis includes especially dissociative identity disorder.

Stress is known to contribute to and trigger psychotic states. A

history of psychologically traumatic events, and the recent experience

of a stressful event, can both contribute to the development of

psychosis. Short-lived psychosis triggered by stress is known as brief reactive psychosis, and patients may spontaneously recover normal functioning within two weeks.

In some rare cases, individuals may remain in a state of full-blown

psychosis for many years, or perhaps have attenuated psychotic symptoms

(such as low intensity hallucinations) present at most times.

Neuroticism is an independent predictor of the development of psychosis.

Subtypes

Subtypes of psychosis include:

- Menstrual psychosis, including circa-mensual (approximately monthly) periodicity, in rhythm with the menstrual cycle.

- Postpartum psychosis, occurring shortly after giving birth

- Monothematic delusions

- Myxedematous psychosis

- Stimulant psychosis

- Tardive psychosis

- Shared psychosis

Cycloid psychosis

Cycloid

psychosis is a psychosis that progresses from normal to full-blown,

usually between a few hours to days, not related to drug intake or brain injury.

The cycloid psychosis has a long history in European psychiatry

diagnosis. The term "cycloid psychosis" was first used by Karl Kleist in

1926. Despite the significant clinical relevance, this diagnosis is

neglected both in literature as in nosology. The cycloid psychosis has

attracted much interest in the international literature of the past 50

years, but the number of scientific studies have greatly decreased over

the past 15 years, possibly partly explained by the misconception that

the diagnosis has been incorporated in current diagnostic classification

systems. The cycloid psychosis is therefore only partially described in

the diagnostic classification systems used. Cycloid psychosis is

nevertheless its own specific disease that is distinct from both the

manic-depressive disorder, and from schizophrenia, and this despite the

fact that the cycloid psychosis can include both bipolar (basic mood

shifts) as well as schizophrenic symptoms. The disease is an acute,

usually self-limiting, functionally psychotic state, with a very diverse

clinical picture that almost consistently is characterized by the

existence of some degree of confusion or distressing perplexity, but

above all, of the multifaceted and diverse expressions the disease

takes. The main features of the disease is thus that the onset is acute,

the multifaceted picture of symptoms and typically reverses to a normal

state and that the long-term prognosis is good. In addition, diagnostic criteria include at least four of the following symptoms:

- Confusion

- Mood-incongruent delusions

- Hallucinations

- Pan-anxiety, a severe anxiety not bound to particular situations or circumstances

- Happiness or ecstasy of high degree

- Motility disturbances of akinetic or hyperkinetic type

- Concern with death

- Mood swings to some degree, but less than what is needed for diagnosis of an affective disorder

Cycloid psychosis occurs in people of generally 15–50 years of age.

Medical conditions

A very large number of medical conditions can cause psychosis, sometimes called secondary psychosis. Examples include:

- disorders causing delirium (toxic psychosis), in which consciousness is disturbed

- neurodevelopmental disorders and chromosomal abnormalities, including velocardiofacial syndrome

- neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and Parkinson's disease

- focal neurological disease, such as stroke, brain tumors, multiple sclerosis, and some forms of epilepsy

- malignancy (typically via masses in the brain, paraneoplastic syndromes)

- infectious and postinfectious syndromes, including infections causing delirium, viral encephalitis, HIV/AIDS, malaria, syphilis

- endocrine disease, such as hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, Cushing's syndrome, hypoparathyroidism and hyperparathyroidism; sex hormones also affect psychotic symptoms and sometimes giving birth can provoke psychosis, termed postpartum psychosis

- inborn errors of metabolism, such as Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency, porphyria and metachromatic leukodystrophy

- nutritional deficiency, such as vitamin B12 deficiency

- other acquired metabolic disorders, including electrolyte disturbances such as hypocalcemia, hypernatremia, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypermagnesemia, hypercalcemia, and hypophosphatemia, but also hypoglycemia, hypoxia, and failure of the liver or kidneys

- autoimmune and related disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus, SLE), sarcoidosis, Hashimoto's encephalopathy, anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis, and non-celiac gluten sensitivity

- poisoning, by therapeutic drugs (see below), recreational drugs (see below), and a range of plants, fungi, metals, organic compounds, and a few animal toxins

- sleep disorders, such as in narcolepsy (in which REM sleep intrudes into wakefulness)

- parasitic diseases, such as neurocysticercosis

Psychoactive drugs

Various psychoactive substances

(both legal and illegal) have been implicated in causing, exacerbating,

or precipitating psychotic states or disorders in users, with varying

levels of evidence. This may be upon intoxication for a more prolonged

period after use, or upon withdrawal.

Individuals who have a substance induced psychosis tend to have a

greater awareness of their psychosis and tend to have higher levels of suicidal thinking compared to individuals who have a primary psychotic illness. Drugs commonly alleged to induce psychotic symptoms include alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, cathinones, psychedelic drugs (such as LSD and psilocybin), κ-opioid receptor agonists (such as enadoline and salvinorin A) and NMDA receptor antagonists (such as phencyclidine and ketamine). Caffeine may worsen symptoms in those with schizophrenia and cause psychosis at very high doses in people without the condition.

Alcohol

Approximately three percent of people who are suffering from alcoholism experience psychosis during acute intoxication or withdrawal. Alcohol related psychosis may manifest itself through a kindling mechanism. The mechanism of alcohol-related psychosis is due to the long-term effects of alcohol resulting in distortions to neuronal membranes, gene expression, as well as thiamin

deficiency. It is possible in some cases that alcohol abuse via a

kindling mechanism can cause the development of a chronic substance

induced psychotic disorder, i.e. schizophrenia. The effects of an

alcohol-related psychosis include an increased risk of depression and

suicide as well as causing psychosocial impairments.

Cannabis

According to some studies, the more often cannabis is used the more likely a person is to develop a psychotic illness, with frequent use being correlated with twice the risk of psychosis and schizophrenia. While cannabis use is accepted as a contributory cause of schizophrenia by some,

it remains controversial, with pre-existing vulnerability to psychosis

emerging as the key factor that influences the link between cannabis use

and psychosis. Some studies indicate that the effects of two active compounds in cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol

(CBD), have opposite effects with respect to psychosis. While THC can

induce psychotic symptoms in healthy individuals, CBD may reduce the

symptoms caused by cannabis.

Cannabis use has increased dramatically over the past few decades

whereas the rate of psychosis has not increased. Together, these

findings suggest that cannabis use may hasten the onset of psychosis in

those who may already be predisposed to psychosis. High-potency cannabis use indeed seems to accelerate the onset of psychosis in predisposed patients.

A 2012 study concluded that cannabis plays an important role in the

development of psychosis in vulnerable individuals, and that cannabis

use in early adolescence should be discouraged.

Methamphetamine

Methamphetamine

induces a psychosis in 26–46 percent of heavy users. Some of these

people develop a long-lasting psychosis that can persist for longer than

six months. Those who have had a short-lived psychosis from

methamphetamine can have a relapse of the methamphetamine psychosis

years later after a stress event such as severe insomnia or a period of

heavy alcohol abuse despite not relapsing back to methamphetamine.

Individuals who have long history of methamphetamine abuse and who have

experienced psychosis in the past from methamphetamine abuse are highly

likely to rapidly relapse back into a methamphetamine psychosis within a

week or so of going back onto methamphetamine.

Medication

Administration, or sometimes withdrawal, of a large number of medications may provoke psychotic symptoms. Drugs that can induce psychosis experimentally or in a significant proportion of people include amphetamine and other sympathomimetics, dopamine agonists, ketamine, corticosteroids (often with mood changes in addition), and some anticonvulsants such as vigabatrin. Stimulants that may cause this include lisdexamfetamine.

Meditation may induce psychological side effects, including depersonalization, derealization and psychotic symptoms like hallucinations as well as mood disturbances.

Pathophysiology

Neuroimaging

The first brain image of an individual with psychosis was completed as far back as 1935 using a technique called pneumoencephalography (a painful and now obsolete procedure where cerebrospinal fluid is drained from around the brain and replaced with air to allow the structure of the brain to show up more clearly on an X-ray picture).

Both first episode psychosis, and high risk status is associated

with reductions in grey matter volume. First episode psychotic and high

risk populations are associated with similar but distinct abnormalities

in GMV. Reductions in the right middle temporal gyrus, right superior temporal gyrus, right parahippocampus, right hippocampus, right middle frontal gyrus, and left anterior cingulate cortex

are observed in high risk populations. Reductions in first episode

psychosis span a region from the right STG to the right insula, left

insula, and cerebellum, and are more severe in the right ACC, right STG,

insula and cerebellum.

Another meta analysis reported similar reductions in temporal, medial

frontal, and insular regions, but also reported increased GMV in the

right lingual gyrus and left precentral gyrus.

The Kraeplinian dichotomy is made questionable by grey matter

abnormalities in bipolar and schizophrenia; schizophrenia is

distinguishable from bipolar in that regions of grey matter reduction

are generally larger in magnitude, although adjusting for gender

differences reduces the difference to the left dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

During attentional tasks, first episode psychosis is associated

with hypoactivation in the right middle frontal gyrus, a region

generally described as encompassing the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC).

In congruence with studies on grey matter volume, hypoactivity in the

right insula, and right inferior parietal lobe is also reported.

With the exceptions of reduced deactivation of the inferior frontal

gyrus during cognitive tasks(i.e. hyperactivation), highly consistent

and replicable hypoactivity in the right insula, dACC, and precuneus, as

well as hyperactivity in the right basal ganglia and thalamus is observed.

Decreased grey matter volume in conjunction with hypoactivity is

observed in the dorsal ACC, right anterior/middle insula, and left

middle insula. Decreased grey matter volume and hyperactivity is

reported in the ventral ACC(i.e. the pgACC and sgACC), and more

posterior regions of the insula.

Hallucinations

Studies

during acute experience of hallucinations demonstrate increased

activity in primary or secondary sensory cortices. As auditory

hallucinations are most common in psychosis, most robust evidence exists

for increased activity in the left middle temporal gyrus, left superior temporal gyrus, and left inferior frontal gyrus (i.e. Broca's area). Activity in the ventral striatum, hippocampus,

and ACC are related to the lucidity of hallucinations, and indicate

that activation or involvement of emotional circuitry are key to the

impact of abnormal activity in sensory cortices. Together, these

findings indicate abnormal processing of internally generated sensory

experiences, coupled with abnormal emotional processing, results in

hallucinations. One proposed model involves a failure of feedforward

networks from sensory cortices to the inferior frontal cortex, which

normally cancel out sensory cortex activity during internally generated

speech. The resulting disruption in expected and perceived speech is

thought to produce lucid hallucinatory experiences.

Delusions

The

two factor model of delusions posits that dysfunction in both belief

formation systems and belief evaluation systems are necessary for

delusions. Dysfunction in evaluations systems localized to the right

lateral prefrontal cortex, regardless of delusion content, is supported

by neuroimaging studies and is congruent with its role in conflict

monitoring in healthy persons. Abnormal activation and reduced volume

is seen in people with delusions, as well as in disorders associated

with delusions such as frontotemporal dementia, psychosis and Lewy body dementia.

Furthermore, lesions to this region are associated with "jumping to

conclusions", damage to this region is associated with post-stroke

delusions, and hypometabolism this region associated with caudate

strokes presenting with delusions.

The aberrant salience model suggests that delusions are a result

of people assigning excessive importance to irrelevant stimuli. In

support of this hypothesis, regions normally associated with the salience network demonstrate reduced grey matter in people with delusions, and the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is widely implicated in salience processing, is also widely implicated in psychotic disorders.

Specific regions have been associated with specific types of

delusions. The volume of the hippocampus and parahippocampus is related

to paranoid delusions in Alzheimer's disease,

and has been reported to be abnormal post mortem in one person with

delusions. Capragas delusions have been associated with

occipito-temporal damage, and may be related to failure to elicit normal

emotions or memories in response to faces.

Negative symptoms

Psychosis is associated with ventral striatal

hypoactivity during reward anticipation and feedback. Hypoactivity in

the left ventral striatum is correlated with the severity of negative

symptoms. While anhedonia is a commonly reported symptom in psychosis, hedonic

experiences are actually intact in most people with schizophrenia. The

impairment that may present itself as anhedonia probably actually lies

in the inability to identify goals, and to identify and engage in the

behaviors necessary to achieve goals.

Studies support a deficiency in the neural representation of goals and

goal directed behavior by demonstrating that receipt (not anticipation)

of reward is associated with robust response in the ventral striatum;

reinforcement learning is intact when contingencies are implicit, but

not when they require explicit processing; reward prediction errors

(during functional neuroimaging studies), particularly positive PEs are

abnormal; ACC response, taken as an indicator of effort allocation, does

not increase with reward or reward probability increase, and is

associated with negative symptoms; deficits in dlPFC activity and

failure to improve performance on cognitive tasks when offered monetary

incentives are present; and dopamine mediated functions are abnormal.

Neurobiology

Psychosis has been traditionally linked to the neurotransmitter dopamine. In particular, the dopamine hypothesis of psychosis

has been influential and states that psychosis results from an

overactivity of dopamine function in the brain, particularly in the mesolimbic pathway. The two major sources of evidence given to support this theory are that dopamine receptor D2 blocking drugs (i.e., antipsychotics)

tend to reduce the intensity of psychotic symptoms, and that drugs that

accentuate dopamine release, or inhibit its reuptake (such as amphetamines and cocaine) can trigger psychosis in some people.

NMDA receptor dysfunction has been proposed as a mechanism in psychosis. This theory is reinforced by the fact that dissociative NMDA receptor antagonists such as ketamine, PCP and dextromethorphan (at large overdoses) induce a psychotic state. The symptoms of dissociative intoxication are also considered to mirror the symptoms of schizophrenia, including negative psychotic symptoms.

NMDA receptor antagonism, in addition to producing symptoms

reminiscent of psychosis, mimics the neurophysiological aspects, such as

reduction in the amplitude of P50, P300, and MMN evoked potentials.

Hierarchical Bayesian neurocomputational models of sensory feedback,

in agreement with neuroimaging literature, link NMDA receptor

hypofunction to delusional or hallucinatory symptoms via proposing a

failure of NMDA mediated top down predictions to adequately cancel out

enhanced bottom up AMPA mediated predictions errors.

Excessive prediction errors in response to stimuli that would normally

not produce such as response is thought to confer excessive salience to

otherwise mundane events. Dsyfunction higher up in the hierarchy, where representation is more abstract, could result in delusions. The common finding of reduced GAD67 expression in psychotic disorders may explain enhanced AMPA mediated signaling, caused by reduced GABAergic inhibition.

The connection between dopamine and psychosis is generally believed complex. While dopamine receptor D2 suppresses adenylate cyclase activity, the D1

receptor increases it. If D2-blocking drugs are administered the

blocked dopamine spills over to the D1 receptors. The increased

adenylate cyclase activity affects genetic expression

in the nerve cell, which takes time. Hence antipsychotic drugs take a

week or two to reduce the symptoms of psychosis. Moreover, newer and

equally effective antipsychotic drugs actually block slightly less

dopamine in the brain than older drugs whilst also blocking 5-HT2A

receptors, suggesting the 'dopamine hypothesis' may be oversimplified. Soyka and colleagues found no evidence of dopaminergic dysfunction in people with alcohol-induced psychosis and Zoldan et al. reported moderately successful use of ondansetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, in the treatment of levodopa psychosis in Parkinson's disease patients.

A review found an association between a first-episode of psychosis and prediabetes.

Prolonged or high dose use of psychostimulants can alter normal functioning, making it similar to the manic phase of bipolar disorder. NMDA antagonists replicate some of the so-called "negative" symptoms like thought disorder in subanesthetic doses (doses insufficient to induce anesthesia), and catatonia

in high doses. Psychostimulants, especially in one already prone to

psychotic thinking, can cause some "positive" symptoms, such as

delusional beliefs, particularly those persecutory in nature.

Diagnosis

To make a diagnosis of a mental illness in someone with psychosis other potential causes must be excluded.

An initial assessment includes a comprehensive history and physical

examination by a health care provider. Tests may be done to exclude

substance use, medication, toxins, surgical complications, or other

medical illnesses. A person with psychosis is referred to as psychotic.

Delirium

should be ruled out, which can be distinguished by visual

hallucinations, acute onset and fluctuating level of consciousness,

indicating other underlying factors, including medical illnesses. Excluding medical illnesses associated with psychosis is performed by using blood tests to measure:

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone to exclude hypo- or hyperthyroidism,

- Basic electrolytes and serum calcium to rule out a metabolic disturbance,

- Full blood count including ESR to rule out a systemic infection or chronic disease, and

- Serology to exclude syphilis or HIV infection.

Other investigations include:

Because psychosis may be precipitated or exacerbated by common classes of medications, medication-induced psychosis should be ruled out, particularly for first-episode psychosis. Both substance- and medication-induced psychosis can be excluded to a high level of certainty, using toxicology screening.

Because some dietary supplements

may also induce psychosis or mania, but cannot be ruled out with

laboratory tests, a psychotic individual's family, partner, or friends

should be asked whether the patient is currently taking any dietary

supplements.

Common mistakes made when diagnosing people who are psychotic include:

- Not properly excluding delirium,

- Not appreciating medical abnormalities (e.g., vital signs),

- Not obtaining a medical history and family history,

- Indiscriminate screening without an organizing framework,

- Missing a toxic psychosis by not screening for substances and medications,

- Not asking family or others about dietary supplements,

- Premature diagnostic closure, and

- Not revisiting or questioning the initial diagnostic impression of primary psychiatric disorder.

Only after relevant and known causes of psychosis are excluded, a mental health clinician may make a psychiatric differential diagnosis

using a person's family history, incorporating information from the

person with psychosis, and information from family, friends, or

significant others.

Types of psychosis in psychiatric disorders may be established by formal rating scales. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) assesses the level of 18 symptom constructs of psychosis such as hostility, suspicion, hallucination, and grandiosity.

It is based on the clinician's interview with the patient and

observations of the patient's behavior over the previous 2–3 days. The

patient's family can also answer questions on the behavior report.

During the initial assessment and the follow-up, both positive and

negative symptoms of psychosis can be assessed using the 30 item

Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS).

The DSM-5

characterizes disorders as psychotic or on the schizophrenia spectrum

if they involve hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking,

grossly disorganized motor behavior, or negative symptoms.

The DSM-5 does not include psychosis as a definition in the glossary,

although it defines "psychotic features", as well as "psychoticism" with

respect to personality disorder. The ICD-10 has no specific definition of psychosis.

Factor analysis

of symptoms generally regarded as psychosis frequently yields a five

factor solution, albeit five factors that are distinct from the five

domains defined by the DSM-5 to encompass psychotic or schizophrenia

spectrum disorders. The five factors are frequently labeled as

hallucinations, delusions, disorganization, excitement, and emotional

distress.

The DSM-5 emphasizes a psychotic spectrum, wherein the low end is

characterized by schizoid personality disorder, and the high end is

characterized by schizophrenia.

Prevention

The evidence for the effectiveness of early interventions to prevent psychosis appeared inconclusive. But psychosis caused by drugs can be prevented.

Whilst early intervention in those with a psychotic episode might

improve short term outcomes, little benefit was seen from these measures

after five years. However, there is evidence that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may reduce the risk of becoming psychotic in those at high risk, and in 2014 the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended preventive CBT for people at risk of psychosis.

Treatment

The

treatment of psychosis depends on the specific diagnosis (such as

schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or substance intoxication). The

first-line treatment for many psychotic disorders is antipsychotic

medication, which can reduce the positive symptoms of psychosis in about 7 to 14 days.

Medication

The choice of which antipsychotic to use is based on benefits, risks, and costs. It is debatable whether, as a class, typical or atypical antipsychotics are better. Tentative evidence supports that amisulpride, olanzapine, risperidone and clozapine may be more effective for positive symptoms but result in more side effects. Typical antipsychotics have equal drop-out and symptom relapse rates to atypicals when used at low to moderate dosages.

There is a good response in 40–50%, a partial response in 30–40%, and

treatment resistance (failure of symptoms to respond satisfactorily

after six weeks to two or three different antipsychotics) in 20% of

people.

Clozapine is an effective treatment for those who respond poorly to

other drugs ("treatment-resistant" or "refractory" schizophrenia), but it has the potentially serious side effect of agranulocytosis (lowered white blood cell count) in less than 4% of people.

Most people on antipsychotics get side effects. People on typical antipsychotics tend to have a higher rate of extrapyramidal side effects while some atypicals are associated with considerable weight gain, diabetes and risk of metabolic syndrome; this is most pronounced with olanzapine, while risperidone and quetiapine are also associated with weight gain. Risperidone has a similar rate of extrapyramidal symptoms to haloperidol.

Counseling

Psychological treatments such as acceptance and commitment therapy

(ACT) are possibly useful in the treatment of psychosis, helping people

to focus more on what they can do in terms of valued life directions

despite challenging symptomology.

Early intervention

Early intervention in psychosis

is based on the observation that identifying and treating someone in

the early stages of a psychosis can improve their longer term outcome. This approach advocates the use of an intensive multi-disciplinary approach during what is known as the critical period, where intervention is the most effective, and prevents the long term morbidity associated with chronic psychotic illness.

History

Etymology

The word psychosis was introduced to the psychiatric literature in 1841 by Karl Friedrich Canstatt in his work Handbuch der Medizinischen Klinik. He used it as a shorthand for 'psychic neurosis'. At that time neurosis meant any disease of the nervous system, and Canstatt was thus referring to what was considered a psychological manifestation of brain disease. Ernst von Feuchtersleben is also widely credited as introducing the term in 1845, as an alternative to insanity and mania.

The term stems from Modern Latin psychosis, "a giving soul or life to, animating, quickening" and that from Ancient Greek ψυχή (psyche), "soul" and the suffix -ωσις (-osis), in this case "abnormal condition".

In its adjective form "psychotic", references to psychosis can be found in both clinical and non-clinical discussions.

Classification

The word was also used to distinguish a condition considered a disorder of the mind, as opposed to neurosis, which was considered a disorder of the nervous system. The psychoses thus became the modern equivalent of the old notion of madness, and hence there was much debate on whether there was only one (unitary) or many forms of the new disease. One type of broad usage would later be narrowed down by Koch in 1891 to the 'psychopathic inferiorities'—later renamed abnormal personalities by Schneider.

The division of the major psychoses into manic depressive illness (now called bipolar disorder) and dementia praecox (now called schizophrenia) was made by Emil Kraepelin, who attempted to create a synthesis of the various mental disorders identified by 19th century psychiatrists,

by grouping diseases together based on classification of common

symptoms. Kraepelin used the term 'manic depressive insanity' to

describe the whole spectrum of mood disorders, in a far wider sense than it is usually used today.

In Kraepelin's classification this would include 'unipolar' clinical depression, as well as bipolar disorder and other mood disorders such as cyclothymia.

These are characterised by problems with mood control and the psychotic

episodes appear associated with disturbances in mood, and patients

often have periods of normal functioning between psychotic episodes even

without medication. Schizophrenia

is characterized by psychotic episodes that appear unrelated to

disturbances in mood, and most non-medicated patients show signs of

disturbance between psychotic episodes.

Treatment

Early

civilizations considered madness a supernaturally inflicted phenomenon.

Archaeologists have unearthed skulls with clearly visible drillings,

some datable back to 5000 BC suggesting that trepanning was a common treatment for psychosis in ancient times. Written record of supernatural causes and resultant treatments can be traced back to the New Testament. Mark 5:8–13 describes a man displaying what would today be described as psychotic symptoms. Christ cured this "demonic

madness" by casting out the demons and hurling them into a herd of

swine. Exorcism is still utilized in some religious circles as a

treatment for psychosis presumed to be demonic possession.

A research study of out-patients in psychiatric clinics found that 30

percent of religious patients attributed the cause of their psychotic

symptoms to evil spirits. Many of these patients underwent exorcistic

healing rituals that, though largely regarded as positive experiences by

the patients, had no effect on symptomology. Results did, however, show

a significant worsening of psychotic symptoms associated with exclusion

of medical treatment for coercive forms of exorcism.

The medical teachings of the fourth-century philosopher and physician Hippocrates of Cos proposed a natural, rather than supernatural, cause of human illness. In Hippocrates' work, the Hippocratic corpus, a holistic explanation for health and disease was developed to include madness and other "diseases of the mind." Hippocrates writes:

Men ought to know that from the brain, and from the brain only, arise our pleasures, joys, laughter, and jests, as well as our sorrows, pains, griefs and tears. Through it, in particular, we think, see, hear, and distinguish the ugly from the beautiful, the bad from the good, the pleasant from the unpleasant…. It is the same thing which makes us mad or delirious, inspires us with dread and fear, whether by night or by day, brings sleeplessness, inopportune mistakes, aimless anxieties, absentmindedness, and acts that are contrary to habit.

Hippocrates espoused a theory of humoralism wherein disease is resultant of a shifting balance in bodily fluids including blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. According to humoralism, each fluid or "humour"

has temperamental or behavioral correlates. In the case of psychosis,

symptoms are thought to be caused by an excess of both blood and yellow

bile. Thus, the proposed surgical intervention for psychotic or manic

behavior was bloodletting.

18th century physician, educator, and widely considered "founder

of American psychiatry", Benjamin Rush, also prescribed bloodletting as a

first-line treatment for psychosis. Although not a proponent of

humoralism, Rush believed that active purging and bloodletting were

efficacious corrections for disruptions in the circulatory system, a

complication he believed was the primary cause of "insanity".

Although Rush's treatment modalities are now considered antiquated and

brutish, his contributions to psychiatry, namely the biological

underpinnings of psychiatric phenomenon including psychosis, have been

invaluable to the field. In honor of such contributions, Benjamin

Rush's image is in the official seal of the American Psychiatric Association.

Early 20th century treatments for severe and persisting psychosis

were characterized by an emphasis on shocking the nervous system. Such

therapies include insulin shock therapy, cardiazol shock therapy, and electroconvulsive therapy. Despite considerable risk, shock therapy was considered highly efficacious in the treatment of psychosis including schizophrenia. The acceptance of high-risk treatments led to more invasive medical interventions including psychosurgery.

In 1888, Swiss psychiatrist Gottlieb Burckhardt performed the first medically sanctioned psychosurgery in which the cerebral cortex

was excised. Although some patients showed improvement of symptoms and

became more subdued, one patient died and several developed aphasia or seizure disorders.

Burckhardt would go on to publish his clinical outcomes in a scholarly

paper. This procedure was met with criticism from the medical

community and his academic and surgical endeavors were largely ignored. In the late 1930s, Egas Moniz conceived the leucotomy (AKA prefrontal lobotomy) in which the fibers connecting the frontal lobes

to the rest of the brain were severed. Moniz’s primary inspiration

stemmed from a demonstration by neuroscientists John Fulton and

Carlyle’s 1935 experiment in which two chimpanzees were given

leucotomies and pre and post surgical behavior was compared. Prior to

the leucotomy, the chimps engaged in typical behavior including throwing

feces and fighting. After the procedure, both chimps were pacified and

less violent. During the Q&A, Moniz asked if such a procedure

could be extended to human subjects, a question that Fulton admitted was

quite startling.

Moniz would go on to extend the controversial practice to humans

suffering from various psychotic disorders, an endeavor for which he

received a Nobel Prize in 1949. Between the late 1930s and early 1970s, the leucotomy was a widely accepted practice, often performed in non-sterile environments such as small outpatient clinics and patient homes. Psychosurgery remained standard practice until the discovery of antipsychotic pharmacology in the 1950s.

The first clinical trial of antipsychotics (also commonly known as neuroleptics) for the treatment of psychosis took place in 1952. Chlorpromazine

(brand name: Thorazine) passed clinical trials and became the first

antipsychotic medication approved for the treatment of both acute and

chronic psychosis. Although the mechanism of action was not discovered

until 1963, the administration of chlorpromazine marked the advent of

the dopamine antagonist, or first generation antipsychotic. While clinical trials showed a high response rate for both acute psychosis and disorders with psychotic features, the side-effects were particularly harsh, which included high rates of often irreversible Parkinsonian symptoms such as tardive dyskinesia. With the advent of atypical antipsychotics

(also known as second generation antipsychotics) came a dopamine

antagonist with a comparable response rate but a far different, though

still extensive, side-effect profile that included a lower risk of

Parkinsonian symptoms but a higher risk of cardiovascular disease. Atypical antipsychotics remain the first-line treatment for psychosis associated with various psychiatric and neurological disorders including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, dementia, and some autism spectrum disorders.

It is now known that dopamine is the primary neurotransmitter

implicated in psychotic symptomology. Thus, blocking dopamine receptors

(namely, the dopamine D2 receptors) and decreasing dopaminergic

activity continues to be an effective but highly unrefined pharmacologic

goal of antipsychotics. Recent pharmacological research suggests that

the decrease in dopaminergic activity does not eradicate psychotic delusions or hallucinations,

but rather attenuates the reward mechanisms involved in the development

of delusional thinking; that is, connecting or finding meaningful

relationships between unrelated stimuli or ideas. The author of this research paper acknowledges the importance of future investigation:

The model presented here is based on incomplete knowledge related to dopamine, schizophrenia, and antipsychotics—and as such will need to evolve as more is known about these.

— Shitij Kapur, From dopamine to salience to psychosis—linking biology, pharmacology and phenomenology of psychosis

Freud´s former student Wilhelm Reich explored independent insights

into the physical effects of neurotic and traumatic upbringing, and

published his holistic psychoanalytic treatment with a schizophrenic.

With his incorporation of breathwork and insight with the patient, a

young woman, she achieved sufficient self-management skills to end the

therapy.

Society

Psychiatrist David Healy

has criticised pharmaceutical companies for promoting simplified

biological theories of mental illness that seem to imply the primacy of

pharmaceutical treatments while ignoring social and developmental

factors that are known important influences in the aetiology of

psychosis.