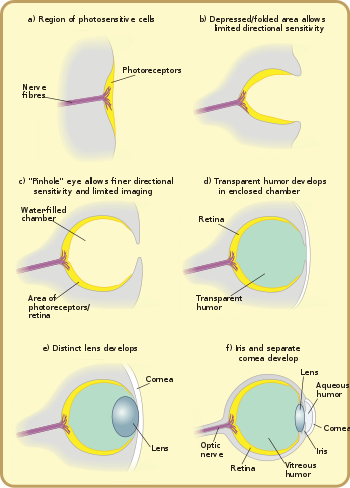

Major stages in the evolution of the eye in vertebrates.

The evolution of the eye is attractive to study, because the eye distinctively exemplifies an analogous organ found in many animal forms. Complex, image-forming eyes have evolved independently between 50 to 100 times.[1]

Complex eyes appeared first within the few million years of the Cambrian explosion. From before the Cambrian, no evidence of eyes has survived, but diverse eyes are known from the Burgess shale of the Middle Cambrian, and from the slightly older Emu Bay Shale.[2] Eyes are adapted to the various requirements of their owners. They vary in their visual acuity, the range of wavelengths they can detect, their sensitivity in low light, their ability to detect motion or to resolve objects, and whether they can discriminate colours.

History of research

The human eye, showing the iris

In 1802, philosopher William Paley called it a miracle of "design". Charles Darwin himself wrote in his Origin of Species, that the evolution of the eye by natural selection seemed at first glance "absurd in the highest possible degree". However, he went on that despite the difficulty in imagining it, its evolution was perfectly feasible:

...if numerous gradations from a simple and imperfect eye to one complex and perfect can be shown to exist, each grade being useful to its possessor, as is certainly the case; if further, the eye ever varies and the variations be inherited, as is likewise certainly the case and if such variations should be useful to any animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, should not be considered as subversive of the theory.[3]He suggested a stepwise evolution from "an optic nerve merely coated with pigment, and without any other mechanism" to "a moderately high stage of perfection", and gave examples of existing intermediate steps.[3] Darwin's suggestions were soon shown to be correct, and current research is investigating the genetic mechanisms underlying eye development and evolution.[4]

Biologist D.E. Nilsson has independently theorized about four general stages in the evolution of a vertebrate eye from a patch of photoreceptors.[5] Nilsson and S. Pelger estimated in a classical paper how many generations are needed to evolve a complex eye in vertebrates.[6] Another researcher, G.C. Young, has used the fossil record to infer evolutionary conclusions, based on the structure of eye orbits and openings in fossilized skulls for blood vessels and nerves to go through.[7] All this adds to the growing amount of evidence that supports Darwin's theory.

Rate of evolution

The first fossils of eyes found to date are from the lower Cambrian period (about 540 million years ago).[8] The lower Cambrian had a burst of apparently rapid evolution, called the "Cambrian explosion". One of the many hypotheses for "causes" of the Cambrian explosion is the "Light Switch" theory of Andrew Parker: It holds that the evolution of eyes started an arms race that accelerated evolution.[9] Before the Cambrian explosion, animals may have sensed light, but did not use it for fast locomotion or navigation by vision.The rate of eye evolution is difficult to estimate, because the fossil record, particularly of the lower Cambrian, is poor. How fast a circular patch of photoreceptor cells evolve into a fully functional vertebrate eye has been estimated based on rates of mutation, relative advantage to the organism, and natural selection. However, the time needed for each state was consistently overestimated and the generation time was set to one year, which is common in small animals. Even with these pessimistic values, the vertebrate eye would still evolve from a patch of photoreceptor cells in less than 364,000 years.[10][note 1]

One origin or many?

Whether the eye evolved once or many times depends on the definition of an eye. All eyed animals share much of the genetic machinery for eye development. This suggests that the ancestor of eyed animals had some form of light-sensitive machinery – even if it was not a dedicated optical organ. However, even photoreceptor cells may have evolved more than once from molecularly similar chemoreceptor cells. Probably, photoreceptor cells existed long before the Cambrian explosion.[11] Higher-level similarities – such as the use of the protein crystallin in the independently derived cephalopod and vertebrate lenses[12] – reflect the co-option of a more fundamental protein to a new function within the eye.[13]A shared trait common to all light-sensitive organs are opsins. Opsins belong to a family of photo-sensitive proteins and fall into nine groups, which already existed in the urbilaterian, the last common ancestor of all bilateral symmetrical animals.[14] Additionally, the genetic toolkit for positioning eyes is shared by all animals: The PAX6 gene controls where eyes develop in animals ranging from octopuses[15] to mice and fruit flies.[16][17][18] Such high-level genes are, by implication, much older than many of the structures that they control today; they must originally have served a different purpose, before they were co-opted for eye development.[13]

Eyes and other sensory organs probably evolved before the brain: There is no need for an information-processing organ (brain) before there is information to process.[19]

Stages of eye evolution

The stigma (2) of the euglena hides a light-sensitive spot.

The earliest predecessors of the eye were photoreceptor proteins that sense light, found even in unicellular organisms, called "eyespots". Eyespots can only sense ambient brightness: they can distinguish light from dark, sufficient for photoperiodism and daily synchronization of circadian rhythms. They are insufficient for vision, as they cannot distinguish shapes or determine the direction light is coming from. Eyespots are found in nearly all major animal groups, and are common among unicellular organisms, including euglena. The euglena's eyespot, called a stigma, is located at its anterior end. It is a small splotch of red pigment which shades a collection of light sensitive crystals. Together with the leading flagellum, the eyespot allows the organism to move in response to light, often toward the light to assist in photosynthesis,[20] and to predict day and night, the primary function of circadian rhythms. Visual pigments are located in the brains of more complex organisms, and are thought to have a role in synchronising spawning with lunar cycles. By detecting the subtle changes in night-time illumination, organisms could synchronise the release of sperm and eggs to maximise the probability of fertilisation.[citation needed]

Vision itself relies on a basic biochemistry which is common to all eyes. However, how this biochemical toolkit is used to interpret an organism's environment varies widely: eyes have a wide range of structures and forms, all of which have evolved quite late relative to the underlying proteins and molecules.[20]

At a cellular level, there appear to be two main "designs" of eyes, one possessed by the protostomes (molluscs, annelid worms and arthropods), the other by the deuterostomes (chordates and echinoderms).[20]

The functional unit of the eye is the photoreceptor cell, which contains the opsin proteins and responds to light by initiating a nerve impulse. The light sensitive opsins are borne on a hairy layer, to maximise the surface area. The nature of these "hairs" differs, with two basic forms underlying photoreceptor structure: microvilli and cilia.[21] In the eyes of protostomes, they are microvilli: extensions or protrusions of the cellular membrane. But in the eyes of deuterostomes, they are derived from cilia, which are separate structures.[20] However, outside the eyes an organism may use the other type of photoreceptor cells, for instance the clamworm Platynereis dumerilii uses microvilliar cells in the eyes but has additionally deep brain ciliary photoreceptor cells.[22] The actual derivation may be more complicated, as some microvilli contain traces of cilia — but other observations appear to support a fundamental difference between protostomes and deuterostomes.[20] These considerations centre on the response of the cells to light – some use sodium to cause the electric signal that will form a nerve impulse, and others use potassium; further, protostomes on the whole construct a signal by allowing more sodium to pass through their cell walls, whereas deuterostomes allow less through.[20]

This suggests that when the two lineages diverged in the Precambrian, they had only very primitive light receptors, which developed into more complex eyes independently.

Early eyes

The basic light-processing unit of eyes is the photoreceptor cell, a specialized cell containing two types of molecules in a membrane: the opsin, a light-sensitive protein, surrounding the chromophore, a pigment that distinguishes colors. Groups of such cells are termed "eyespots", and have evolved independently somewhere between 40 and 65 times. These eyespots permit animals to gain only a very basic sense of the direction and intensity of light, but not enough to discriminate an object from its surroundings.[20]Developing an optical system that can discriminate the direction of light to within a few degrees is apparently much more difficult, and only six of the thirty-some phyla[note 2] possess such a system. However, these phyla account for 96% of living species.[20]

The planarian has "cup" eyespots that can slightly distinguish light direction.

These complex optical systems started out as the multicellular eyepatch gradually depressed into a cup, which first granted the ability to discriminate brightness in directions, then in finer and finer directions as the pit deepened. While flat eyepatches were ineffective at determining the direction of light, as a beam of light would activate exactly the same patch of photo-sensitive cells regardless of its direction, the "cup" shape of the pit eyes allowed limited directional differentiation by changing which cells the lights would hit depending upon the light's angle. Pit eyes, which had arisen by the Cambrian period, were seen in ancient snails,[clarification needed] and are found in some snails and other invertebrates living today, such as planaria. Planaria can slightly differentiate the direction and intensity of light because of their cup-shaped, heavily pigmented retina cells, which shield the light-sensitive cells from exposure in all directions except for the single opening for the light. However, this proto-eye is still much more useful for detecting the absence or presence of light than its direction; this gradually changes as the eye's pit deepens and the number of photoreceptive cells grows, allowing for increasingly precise visual information.[23]

When a photon is absorbed by the chromophore, a chemical reaction causes the photon's energy to be transduced into electrical energy and relayed, in higher animals, to the nervous system. These photoreceptor cells form part of the retina, a thin layer of cells that relays visual information,[24] including the light and day-length information needed by the circadian rhythm system, to the brain. However, some jellyfish, such as Cladonema, have elaborate eyes but no brain. Their eyes transmit a message directly to the muscles without the intermediate processing provided by a brain.[19]

During the Cambrian explosion, the development of the eye accelerated rapidly, with radical improvements in image-processing and detection of light direction.[25]

The primitive nautilus eye functions similarly to a pinhole camera.

After the photosensitive cell region invaginated, there came a point when reducing the width of the light opening became more efficient at increasing visual resolution than continued deepening of the cup.[10] By reducing the size of the opening, organisms achieved true imaging, allowing for fine directional sensing and even some shape-sensing. Eyes of this nature are currently found in the nautilus. Lacking a cornea or lens, they provide poor resolution and dim imaging, but are still, for the purpose of vision, a major improvement over the early eyepatches.[26]

Overgrowths of transparent cells prevented contamination and parasitic infestation. The chamber contents, now segregated, could slowly specialize into a transparent humour, for optimizations such as colour filtering, higher refractive index, blocking of ultraviolet radiation, or the ability to operate in and out of water. The layer may, in certain classes, be related to the moulting of the organism's shell or skin. An example of this can be observed in Onychophorans where the cuticula of the shell continues to the cornea. The cornea is composed of either one or two cuticular layers depending on how recently the animal has moulted.[27] Along with the lens and two humors, the cornea is responsible for converging light and aiding the focusing of it on the back of the retina. The cornea protects the eyeball while at the same time accounting for approximately 2/3 of the eye’s total refractive power.[28]

It is likely that a key reason eyes specialize in detecting a specific, narrow range of wavelengths on the electromagnetic spectrum—the visible spectrum—is because the earliest species to develop photosensitivity were aquatic, and only two specific wavelength ranges of electromagnetic radiation, blue and green visible light, can travel through water. This same light-filtering property of water also influenced the photosensitivity of plants.[29][30][31]

Lens formation and diversification

Light from a distant object and a near object being focused by changing the curvature of the lens

In a lensless eye, the light emanating from a distant point hits the back of the eye with about the same size as the eye's aperture. With the addition of a lens this incoming light is concentrated on a smaller surface area, without reducing the overall intensity of the stimulus.[6] The focal length of an early lobopod with lens-containing simple eyes focused the image behind the retina, so while no part of the image could be brought into focus, the intensity of light allowed the organism to see in deeper (and therefore darker) waters.[27] A subsequent increase of the lens's refractive index probably resulted in an in-focus image being formed.[27]

The development of the lens in camera-type eyes probably followed a different trajectory. The transparent cells over a pinhole eye's aperture split into two layers, with liquid in between.[citation needed] The liquid originally served as a circulatory fluid for oxygen, nutrients, wastes, and immune functions, allowing greater total thickness and higher mechanical protection. In addition, multiple interfaces between solids and liquids increase optical power, allowing wider viewing angles and greater imaging resolution. Again, the division of layers may have originated with the shedding of skin; intracellular fluid may infill naturally depending on layer depth.[citation needed]

Note that this optical layout has not been found, nor is it expected to be found. Fossilization rarely preserves soft tissues, and even if it did, the new humour would almost certainly close as the remains desiccated, or as sediment overburden forced the layers together, making the fossilized eye resemble the previous layout.

Compound eye of Antarctic krill

Vertebrate lenses are composed of adapted epithelial cells which have high concentrations of the protein crystallin. These crystallins belong to two major families, the α-crystallins and the βγ-crystallins. Both were categories of proteins originally used for other functions in organisms, but eventually were adapted for the sole purpose of vision in animal eyes.[32] In the embryo, the lens is living tissue, but the cellular machinery is not transparent so must be removed before the organism can see. Removing the machinery means the lens is composed of dead cells, packed with crystallins. These crystallins are special because they have the unique characteristics required for transparency and function in the lens such as tight packing, resistance to crystallization, and extreme longevity, as they must survive for the entirety of the organism’s life.[32] The refractive index gradient which makes the lens useful is caused by the radial shift in crystallin concentration in different parts of the lens, rather than by the specific type of protein: it is not the presence of crystallin, but the relative distribution of it, that renders the lens useful.[33]

It is biologically difficult to maintain a transparent layer of cells. Deposition of transparent, nonliving, material eased the need for nutrient supply and waste removal. Trilobites used calcite, a mineral which today is known to be used for vision only in a single species of brittle star.[34] In other compound eyes[verification needed] and camera eyes, the material is crystallin. A gap between tissue layers naturally forms a biconvex shape, which is optically and mechanically ideal for substances of normal[clarification needed] refractive index. A biconvex lens confers not only optical resolution, but aperture and low-light ability, as resolution is now decoupled from hole size – which slowly increases again, free from the circulatory constraints.

Independently, a transparent layer and a nontransparent layer may split forward from the lens: a separate cornea and iris. (These may happen before or after crystal deposition, or not at all.) Separation of the forward layer again forms a humour, the aqueous humour. This increases refractive power and again eases circulatory problems. Formation of a nontransparent ring allows more blood vessels, more circulation, and larger eye sizes. This flap around the perimeter of the lens also masks optical imperfections, which are more common at lens edges. The need to mask lens imperfections gradually increases with lens curvature and power, overall lens and eye size, and the resolution and aperture needs of the organism, driven by hunting or survival requirements. This type is now functionally identical to the eye of most vertebrates, including humans. Indeed, "the basic pattern of all vertebrate eyes is similar."[35]

Other developments

Color vision

Five classes of visual pigmentation are found in vertebrates. All but one of these developed prior to the divergence of cyclometers and fish.[36] Various adaptations within these five classes give rise to suitable eyes depending on the spectrum encountered. As light travels through water, longer wavelengths, such as reds and yellows, are absorbed more quickly than the shorter wavelengths of the greens and blues. This can create a gradient of light types as the depth of water increases. The visual receptors in fish are more sensitive to the range of light present in their habitat level. However, this phenomenon does not occur in land environments, creating little variation in pigment sensitivities among terrestrial vertebrates. The homogeneous nature of the pigment sensitivities directly contributes to the significant presence of communication colors.[36] This presents distinct selective advantages, such as better recognition of predators, food, and mates. Indeed, it is thought[by whom?] that simple sensory-neural mechanisms may selectively control general behavior patterns, such as escape, foraging, and hiding. Many examples of wavelength-specific behavior patterns have been identified, in two primary groups: less than 450 nm, associated with natural light sources, and greater than 450 nm, associated with reflected light sources.[37] As opsin molecules were subtly fine-tuned to detect different wavelengths of light, at some point color vision developed when photo-receptor cells developed multiple pigments.[24] As a chemical adaptation rather than a mechanical one, this may have occurred at any of the early stages of the eye's evolution, and the capability may have disappeared and reappeared as organisms became predator or prey. Similarly, night and day vision emerged when receptors differentiated into rods and cones, respectively.[citation needed]Polarization vision

As discussed earlier, the properties of light under water differ from those in air. One example of this is the polarization of light. Polarization is the organization of originally disordered light, from the sun, into linear arrangements. This occurs when light passes through slit like filters, as well as when passing into a new medium. Sensitivity to polarized light is especially useful for organisms whose habitats are located more than a few meters under water. In this environment, color vision is less dependable, and therefore a weaker selective factor. While most photoreceptors have the ability to distinguish partially polarized light, terrestrial vertebrates’ membranes are orientated perpendicularly, such that they are insensitive to polarized light.[38] However, some fish can discern polarized light, demonstrating that they possess some linear photoreceptors. Additionally, cuttlefish are capable of perceiving the polarization of light with high visual fidelity, although they appear to lack any significant capacity for color differentiation.[39] Like color vision, sensitivity to polarization can aid in an organism's ability to differentiate surrounding objects and individuals. Because of the marginal reflective interference of polarized light, it is often used for orientation and navigation, as well as distinguishing concealed objects, such as disguised prey.[38]Focusing mechanism

By utilizing the iris sphincter muscle, some species move the lens back and forth, some stretch the lens flatter. Another mechanism regulates focusing chemically and independently of these two, by controlling growth of the eye and maintaining focal length. In addition, the pupil shape can be used to predict the focal system being utilized. A slit pupil can indicate the common multifocal system, while a circular pupil usually specifies a monofocal system. When using a circular form, the pupil will constrict under bright light, increasing the focal length, and will dilate when dark in order to decrease the depth of focus.[40] Note that a focusing method is not a requirement. As photographers know, focal errors increase as aperture increases. Thus, countless organisms with small eyes are active in direct sunlight and survive with no focus mechanism at all. As a species grows larger, or transitions to dimmer environments, a means of focusing need only appear gradually.Location

Prey generally have eyes on the sides of their head so to have a larger field of view, from which to avoid predators. Predators, however, have eyes in front of their head in order to have better depth perception.[41][42] Flatfish are predators which lie on their side on the bottom, and have eyes placed asymmetrically on the same side of the head. A transitional fossil from the common symmetric position is Amphistium.Evolutionary baggage

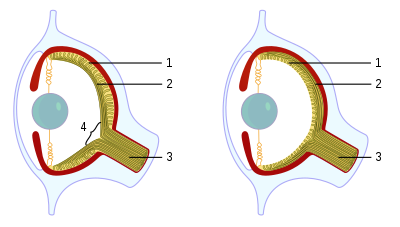

The eyes of many animals record their evolutionary history in their contemporary anatomy. The vertebrate eye, for instance, is built "backwards and upside down", requiring "photons of light to travel through the cornea, lens, aqueous fluid, blood vessels, ganglion cells, amacrine cells, horizontal cells, and bipolar cells before they reach the light-sensitive rods and cones that transduce the light signal into neural impulses, which are then sent to the visual cortex at the back of the brain for processing into meaningful patterns."[43] While such a construct has some drawbacks, it also allows the outer retina of the vertebrates to sustain higher metabolic activities as compared to the non-inverted design.[44] It also allowed for the evolution of the choroid layer, including the retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, which play an important role in protecting the photoreceptive cells from photo-oxidative damage.[45][46]

The camera eyes of cephalopods, in contrast, are constructed the "right way out", with the nerves attached to the rear of the retina. This means that they do not have a blind spot. This difference may be accounted for by the origins of eyes; in cephalopods they develop as an invagination of the head surface whereas in vertebrates they originate as an extension of the brain.[47]