Ebola virus

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Species Zaire ebolavirus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group V ((-)ssRNA) |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Filoviridae |

| Genus: | Ebolavirus |

| Species: | Zaire ebolavirus |

| Member virus (Abbreviation) | |

| Ebola virus (EBOV) | |

Ebola virus (formerly officially designated Zaire ebolavirus, or EBOV) is a virological taxon species included in the genus Ebolavirus, family Filoviridae, members are called Filovirus,[1] the order is Mononegavirales.[2] The Zaire ebolavirus is the most dangerous of the five species of Ebola viruses of the Ebolavirus genus which are the causative agents of Ebola virus disease.[2] The virus causes an extremely severe hemorrhagic fever in humans and other primates. EBOV is a select agent, World Health Organization Risk Group 4 Pathogen (requiring Biosafety Level 4-equivalent containment), a U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Category A Priority Pathogen, U.S. CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Category A Bioterrorism Agent, and listed as a Biological Agent for Export Control by the Australia Group.

The name Zaire ebolavirus is derived from Zaire, the country (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in which the Ebola virus was first discovered, and the taxonomic suffix ebolavirus (which denotes an ebolavirus species).[2]

The EBOV genome is approximately 19 kb in length. It encodes seven structural proteins: nucleoprotein (NP), polymerase cofactor (VP35), (VP40), GP, transcription activator (VP30), VP24, and RNA polymerase (L).[3]

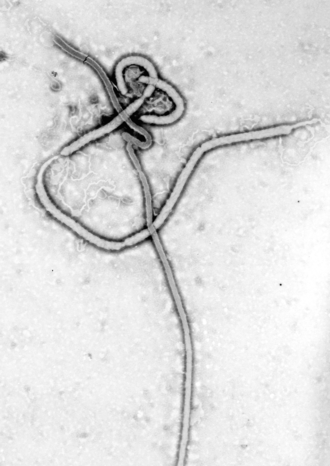

Structure

EBOV carries a negative-sense RNA genome in virions that are cylindrical/tubular, and contain viral envelope, matrix, and nucleocapsid components. The overall cylinders are generally approx. 80 nm in diameter, and having a virally encoded glycoprotein (GP) projecting as 7-10 nm long spikes from its lipid bilayer surface.[4] The cylinders are of variable length, typically 800 nm, but sometimes up to 1000 nm long. The outer viral envelope of the virion is derived by budding from domains of host cell membrane into which the GP spikes have been inserted during their biosynthesis.[citation needed] Individual GP molecules appear with spacings of about 10 nm.[citation needed] Viral proteins VP40 and VP24 are located between the envelope and the nucleocapsid (see following), in the matrix space.[5]

At the center of the virion structure is the nucleocapsid, which is composed of a series of viral proteins attached to a 18-19 kb linear, negative-sense RNA without 3′-polyadenylation or 5′-capping (see following);[citation needed] the RNA is helically wound and complexed with the NP, VP35, VP30, and L proteins;[6][better source needed] this helix has a diameter of 80 nm and contains a central channel of 20–30 nm in diameter.

The overall shape of the virions after purification and visualization (e.g., by ultracentrifugation and electron microscopy, respectively) varies considerably; simple cylinders are far less prevalent than structures showing reversed direction, branches, and loops (i.e., U-, shepherd's crook-, 9- or eye bolt-shapes, or other or circular/coiled appearances), the origin of which may be in the laboratory techniques applied.[7] The characteristic "threadlike" structure is, however, a more general morphologic characteristic of filoviruses (alongside their GP-decorated viral envelope, RNA nucleocapsid, etc.).[8]

Genome |

Each virion contains one molecule of linear, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA, 18,959 to 18,961 nucleotides in length. The 3′ terminus is not polyadenylated and the 5′ end is not capped. It was found that 472 nucleotides from the 3' end and 731 nucleotides from the 5' end are sufficient for replication.[9] It codes for seven structural proteins and one non-structural protein. The gene order is 3′ – leader – NP – VP35 – VP40 – GP/sGP – VP30 – VP24 – L – trailer – 5′; with the leader and trailer being non-transcribed regions, which carry important signals to control transcription, replication, and packaging of the viral genomes into new virions. The genomic material by itself is not infectious, because viral proteins, among them the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, are necessary to transcribe the viral genome into mRNAs because it is a negative sense RNA virus, as well as for replication of the viral genome. Sections of the NP and the L genes from filoviruses have been identified as endogenous in the genomes of several groups of small mammals.[10]

Entry |

Host-encoded Niemann–Pick C1 (NPC1), a cholesterol transporter protein, appears to be essential for entry of Ebola virions into the host cell, and for its ultimate replication.[11][12] In one study, mice that were heterozygous for NPC1 were shown to be protected from lethal challenge with mouse-adapted Ebola virus.[ambiguous][jargon][11] In another study, small molecules were shown to inhibit Ebola virus infection by preventing viral envelope glycoprotein (GP) from binding to NPC1.[12][13] Hence, NPC1 was shown to be critical to entry of this filovirus, because it mediates infection by binding directly to viral GP.[12]

When cells from Niemann Pick Type C patients lacking this transporter were exposed to Ebola virus in the laboratory, the cells survived and appeared impervious to the virus, further indicating that Ebola relies on NPC1 to enter cells;[citation needed] mutations in the NPC1 gene in humans were conjectured as a possible mode to make some individuals resistant to this deadly viral disease.[citation needed][speculation?] The same studies[which?] described similar results regarding NPC1's role in virus entry for Marburg virus, a related filovirus. A further study has also presented evidence that NPC1 is critical receptor mediating Ebola infection via its direct binding to the viral GP, and that it is the second "lysosomal" domain of NPC1 that mediates this binding.[14] Together, these studies suggest NPC1 may be potential therapeutic target for an Ebola anti-viral drug.[citation needed]

Replication |

Being acellular, viruses such as Ebola do not replicate through any type of cell division; rather, they use a combination of host- and virally encoded enzymes, alongside host cell structures, to produce multiple copies of themselves; these then self-assemble into viral macromolecular structures in the host cell.[6][better source needed] Specific steps for Ebola virus include:[citation needed]

- The virus attaches to host receptors through the glycoprotein (GP) surface peplomer and is endocytosed into macropinosomes in the host cell.[15][non-primary source needed]

- Viral membrane fuses with vesicle membrane, nucleocapsid is released into the cytoplasm.

- Encapsidated, negative-sense genomic ssRNA is used as a template for the synthesis (3'-5') of polyadenylated, monocistronic mRNAs.[jargon]

- Using the host cell's ribosomes, tRNA molecules, etc., the mRNA is translated into individual viral proteins.

- Viral proteins are processed, glycoprotein precursor (GP0) is cleaved to GP1 and GP2, which are then heavily glycosylated using cellular enzymes and substrates. These two molecules assemble, first into heterodimers, and then into trimers to give the surface peplomers. Secreted glycoprotein (sGP) precursor is cleaved to sGP and delta peptide, both of which are released from the cell.[citation needed]

- As viral protein levels rise, a switch occurs from translation to replication. Using the negative-sense genomic RNA as a template, a complementary +ssRNA is synthesized; this is then used as a template for the synthesis of new genomic (-)ssRNA, which is rapidly encapsidated.

- The newly formed nucleocapsids and envelope proteins associate at the host cell's plasma membrane; budding occurs, destroying the cell.

Types

The five characterised Ebola species are:

- Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV; previously ZEBOV)

- Also known simply as the Zaire virus, ZEBOV has the highest case-fatality rate of the ebolaviruses, up to 90% in some epidemics, with an average case fatality rate of approximately 83% over 27 years. There have been more outbreaks of Zaire ebolavirus than of any other species. The first outbreak occurred on 26 August 1976 in Yambuku.[16] The first recorded case was Mabalo Lokela, a 44‑year-old schoolteacher. The symptoms resembled malaria, and subsequent patients received quinine. Transmission has been attributed to reuse of unsterilized needles and close personal contact.

- Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV; previously SEBOV)

- Like the Zaire virus, SEBOV emerged in 1976; it was at first assumed identical with the Zaire species.[17] SEBOV is believed to have broken out first among cotton factory workers in Nzara, Sudan (now South Sudan), with the first case reported as a worker exposed to a potential natural reservoir. The virus was not found in any of the local animals and insects that were tested in response. The carrier is still unknown. The lack of barrier nursing (or "bedside isolation") facilitated the spread of the disease. The most recent outbreak occurred in May, 2004. Twenty confirmed cases were reported in Yambio County, Sudan (now South Sudan), with five deaths resulting. The average fatality rates for SEBOV were 54% in 1976, 68% in 1979, and 53% in 2000 and 2001.

- Reston ebolavirus (RESTV; previously REBOV)

- Discovered during an outbreak of simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) in crab-eating macaques from Hazleton Laboratories (now Covance) in 1989. Since the initial outbreak in Reston, Virginia, it has since been found in non-human primates in Pennsylvania, Texas and Siena, Italy. In each case, the affected animals had been imported from a facility in the Philippines,[18] where the virus has also infected pigs.[19] Despite having a Biosafety status of Level‑4 and its apparent pathogenicity in monkeys, REBOV did not cause disease in exposed human laboratory workers.[20]

- Côte d'Ivoire ebolavirus (TAFV; previously CIEBOV)

- Also referred to as Taï Forest ebolavirus and by the English place name, "Ivory Coast", it was first discovered among chimpanzees from the Taï Forest in Côte d'Ivoire, Africa, in 1994. Necropsies showed blood within the heart was brown, no obvious marks were seen on the organs, and one necropsy showed lungs filled with blood. Studies of tissue taken from the chimpanzees showed results similar to human cases during the 1976 Ebola outbreaks in Zaire and Sudan. As more dead chimpanzees were discovered, many tested positive for Ebola using molecular techniques. Experts believed the source of the virus was the meat of infected Western Red Colobus monkeys, upon which the chimpanzees preyed. One of the scientists performing the necropsies on the infected chimpanzees contracted Ebola. She developed symptoms similar to those of dengue fever approximately a week after the necropsy, and was transported to Switzerland for treatment. She was discharged from the hospital after two weeks and had fully recovered six weeks after the infection.[21]

- Bundibugyo ebolavirus (BDBV; previously BEBOV)

- On 24 November 2007, the Uganda Ministry of Health confirmed an outbreak of Ebolavirus in the Bundibugyo District. After confirmation of samples tested by the United States National Reference Laboratories and the CDC, the World Health Organization confirmed the presence of the new species. On 20 February 2008, the Uganda Ministry officially announced the end of the epidemic in Bundibugyo, with the last infected person discharged on 8 January 2008.[22] An epidemiological study conducted by WHO and Uganda Ministry of Health scientists determined there were 116 confirmed and probable cases of the new Ebola species, and that the outbreak had a mortality rate of 34% (39 deaths). In 2012, there was an outbreak of Bundibugyo ebolavirus in a northeastern province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. There were 15 confirmed cases and 10 fatalities.[23]

History

Zaire ebolavirus is pronounced /zɑːˈɪər iːˈboʊləvaɪərəs/ (zah-EER ee-BOH-lə-vy-rəs). Strictly speaking, the pronunciation of "Ebola virus" (/iːˌboʊlə ˈvaɪərəs/) should be distinct from that of the genus-level taxonomic designation "ebolavirus/Ebolavirus/ebolavirus", as "Ebola" is named for the tributary of the Congo River that is pronounced "Ébola" in French,[24] whereas "ebola-virus" is an "artificial contraction" of the words "Ebola" and "virus," written without a diacritical mark for ease of use by scientific databases and English speakers. According to the rules for taxon naming established by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), the name Zaire ebolavirus is always to be capitalized, italicized, and to be preceded by the word "species". The names of its members (Zaire ebolaviruses) are to be capitalized, are not italicized, and used without articles.[2]Ebola virus (abbreviated EBOV) was first described in 1976.[25][26][27] Today, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses lists the virus is the single member of the species Zaire ebolavirus, which is included into the genus Ebolavirus, family Filoviridae, order Mononegavirales.

The name Ebola virus is derived from the Ebola River - a river that was at first thought to be in close proximity to the area in Democratic Republic of Congo, previously called Zaire, where the first recorded Ebola virus disease outbreak occurred - and the taxonomic suffix virus.[2]

The species was introduced in 1998 as Zaire Ebola virus.[28][29] In 2002, the name was changed to Zaire ebolavirus.[30][31]

Previous names

Ebola virus was first introduced as a possible new "strain" of Marburg virus in 1977 by two different research teams.[25][26] At the same time, a third team introduced the name Ebola virus.[27] In 2000, the virus name was changed to Zaire Ebola virus,[32][33] and in 2005 to Zaire ebolavirus.[30][34] However, most scientific articles continued to refer to Ebola virus or used the terms Ebola virus and Zaire ebolavirus in parallel. Consequently, in 2010, the name Ebola virus was reinstated.[2] Previous abbreviations for the virus were EBOV-Z (for Ebola virus Zaire) and most recently ZEBOV (for Zaire Ebola virus or Zaire ebolavirus). In 2010, EBOV was reinstated as the abbreviation for the virus.[2]Species inclusion criteria

- it is found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, or the Republic of the Congo

- it has a genome with two or three gene overlaps (VP35/VP40, GP/VP30, VP24/L)

- it has a genomic sequence that differs from the type virus by less than 30%

Epidemiology

| Year | Geographic location | Human cases/deaths (case-fatality rate) |

|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Yambuku, Zaire | 318/280 (88%) |

| 1976 | Sudan, Sudan | 284/151 (53%) |

| 1977 | Bonduni, Zaire | 1/1 (100%) |

| 1988 | Porton Down, United Kingdom | 1/0 (0%) [laboratory accident] |

| 1994–1995- | Woleu-Ntem and Ogooué-Ivindo Provinces, Gabon | 52/32 (62%) |

| 1995 | Kikwit, Zaire | 317/245 (77%) |

| 1996 | Mayibout 2, Gabon | 31/21 (68%) |

| 1996 | Sergiyev Posad, Russia | 1/1 (100%) [laboratory accident] |

| 1996–1997 | Ogooué-Ivindo Province, Gabon; Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | 62/46 (74%) |

| 2001–2002 | Ogooué-Ivindo Province, Gabon; Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | 124/97 (78%) |

| 2002 | Ogooué-Ivindo Province, Gabon; Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | 11/10 (91%) |

| 2002–2003 | Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo; Ogooué-Ivindo Province, Gabon | 143/128 (90%) |

| 2003–2004 | Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | 35/29 (83%) |

| 2004 | Koltsovo, Russia | 1/1 (100%) [laboratory accident] |

| 2005 | Cuvette-Ouest Department, Republic of the Congo | 11/9 (82%) |

| 2008–2009 | Kasai Occidental Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo | 32/15 (47%) |

| 2014 | Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia (2014 West Africa Ebola outbreak) | 1711/932 (54%) (6 August 2014) |