Leviathan (book)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

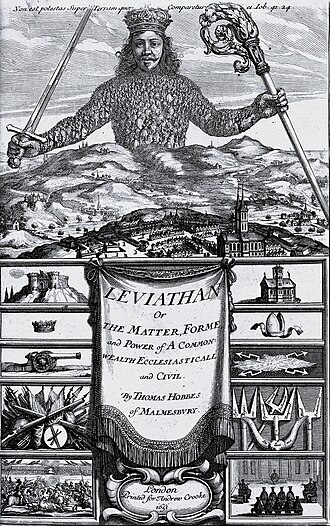

Frontispiece of "Leviathan," by Abraham Bosse, with input from Hobbes.

| |

| Author | Thomas Hobbes |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English, Latin |

Publication date

| 1651 |

| ISBN | 978-1439297254 |

Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil—commonly referred to as Leviathan—is a book written by Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and published in 1651. Its name derives from the biblical Leviathan. The work concerns the structure of society and legitimate government, and is regarded as one of the earliest and most influential examples of social contract theory.[1] Leviathan ranks as a classic western work on statecraft comparable to Machiavelli's The Prince. Written during the English Civil War (1642–1651), Leviathan argues for a social contract and rule by an absolute sovereign. Hobbes wrote that civil war and the brute situation of a state of nature ("the war of all against all") could only be avoided by strong undivided government.

Content

Frontispiece

After lengthy discussion with Hobbes, the Parisian Abraham Bosse created the etching for the book's famous frontispiece in the géometrique style which Bosse himself had refined. It is similar in organisation to the frontispiece of Hobbes' De Cive (1642), created by Jean Matheus. The frontispiece has two main elements, of which the upper part is by far the more striking.In it, a giant crowned figure is seen emerging from the landscape, clutching a sword and a crosier, beneath a quote from the Book of Job—"Non est potestas Super Terram quae Comparetur ei. Iob. 41 . 24" ("There is no power on earth to be compared to him. Job 41 . 24")—linking the figure to the monster of that book. (Because of disagreement over where chapters begin, the verse Hobbes quotes is usually given as Job 41:33 in modern Christian translations into English, Job 41:25 in the Masoretic text, Septuagint, and the Luther Bible; it is 41:24 in the Vulgate.) The torso and arms of the figure are composed of over three hundred persons, in the style of Giuseppe Arcimboldo; all are facing inwards with just the giant's head having visible features. (A manuscript of Leviathan created for Charles II in 1651 has notable differences – a different main head but significantly the body is also composed of many faces, all looking outwards from the body and with a range of expressions.)

The lower portion is a triptych, framed in a wooden border. The centre form contains the title on an ornate curtain. The two sides reflect the sword and crosier of the main figure – earthly power on the left and the powers of the church on the right. Each side element reflects the equivalent power – castle to church, crown to mitre, cannon to excommunication, weapons to logic, and the battlefield to the religious courts. The giant holds the symbols of both sides, reflecting the union of secular and spiritual in the sovereign, but the construction of the torso also makes the figure the state.

Part I: Of Man

Hobbes begins his treatise on politics with an account of human nature. He presents an image of man as matter in motion, attempting to show through example how everything about humanity can be explained materialistically, that is, without recourse to an incorporeal, immaterial soul or a faculty for understanding ideas that are external to the human mind. Hobbes proceeds by defining terms clearly, and in an unsentimental way. Good and evil are nothing more than terms used to denote an individual's appetites and desires, while these appetites and desires are nothing more than the tendency to move toward or away from an object. Hope is nothing more than an appetite for a thing combined with opinion that it can be had. He suggests the dominant political theology of the time, Scholasticism, thrives on confused definitions of everyday words, such as incorporeal substance, which for Hobbes is a contradiction in terms.Hobbes describes human psychology without any reference to the summum bonum, or greatest good, as previous thought had done. Not only is the concept of a summum bonum superfluous, but given the variability of human desires, there could be no such thing. Consequently, any political community that sought to provide the greatest good to its members would find itself driven by competing conceptions of that good with no way to decide among them. The result would be civil war.

There is, however, Hobbes states, a summum malum, or greatest evil. This is the fear of violent death. A political community can be oriented around this fear.

Since there is no summum bonum, the natural state of man is not to be found in a political community that pursues the greatest good. But to be outside of a political community is to be in an anarchic condition. Given human nature, the variability of human desires, and need for scarce resources to fulfill those desires, the state of nature, as Hobbes calls this anarchic condition, must be a war of all against all. Even when two men are not fighting, there is no guarantee that the other will not try to kill him for his property or just out of an aggrieved sense of honour, and so they must constantly be on guard against one another. It is even reasonable to preemptively attack one's neighbour.

In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently, not culture of the earth, no navigation, nor the use of commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth, no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.[2]The desire to avoid the state of nature, as the place where the summum malum of violent death is most likely to occur, forms the polestar of political reasoning. It suggests a number of laws of nature, although Hobbes is quick to point out that they cannot properly speaking be called "laws," since there is no one to enforce them. The first thing that reason suggests is to seek peace, but that where peace cannot be had, to use all of the advantages of war.[3] Hobbes is explicit that in the state of nature nothing can be considered just or unjust, and every man must be considered to have a right to all things.[4] The second law of nature is that one ought to be willing to renounce one's right to all things where others are willing to do the same, to quit the state of nature, and to erect a commonwealth with the authority to command them in all things. Hobbes concludes Part One by articulating an additional seventeen laws of nature that make the performance of the first two possible and by explaining what it would mean for a sovereign to represent the people even when they disagree with the sovereign.

Part II: Of Common-wealth

The purpose of a commonwealth is given at the start of Part II:THE final cause, end, or design of men (who naturally love liberty, and dominion over others) in the introduction of that restraint upon themselves, in which we see them live in Commonwealths, is the foresight of their own preservation, and of a more contented life thereby; that is to say, of getting themselves out from that miserable condition of war which is necessarily consequent, as hath been shown, to the natural passions of men when there is no visible power to keep them in awe, and tie them by fear of punishment to the performance of their covenants...The commonwealth is instituted when all agree in the following manner: I authorise and give up my right of governing myself to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition; that thou give up, thy right to him, and authorise all his actions in like manner.

The sovereign has twelve principal rights:

- because a successive covenant cannot override a prior one, the subjects cannot (lawfully) change the form of government.

- because the covenant forming the commonwealth results from subjects giving to the sovereign the right to act for them, the sovereign cannot possibly breach the covenant; and therefore the subjects can never argue to be freed from the covenant because of the actions of the sovereign.

- the sovereign exists because the majority has consented to his rule; the minority have agreed to abide by this arrangement and must then assent to the sovereign's actions.

- every subject is author of the acts of the sovereign: hence the sovereign cannot injure any of his subjects and cannot be accused of injustice.

- following this, the sovereign cannot justly be put to death by the subjects.

- because the purpose of the commonwealth is peace, and the sovereign has the right to do whatever he thinks necessary for the preserving of peace and security and prevention of discord. Therefore, the sovereign may judge what opinions and doctrines are averse, who shall be allowed to speak to multitudes, and who shall examine the doctrines of all books before they are published.

- to prescribe the rules of civil law and property.

- to be judge in all cases.

- to make war and peace as he sees fit and to command the army.

- to choose counsellors, ministers, magistrates and officers.

- to reward with riches and honour or to punish with corporal or pecuniary punishment or ignominy.

- to establish laws about honour and a scale of worth.

Types of commonwealth[edit]

There are three (monarchy, aristocracy and democracy):The difference of Commonwealths consisted in the difference of the sovereign, or the person representative of all and every one of the multitude. And because the sovereignty is either in one man, or in an assembly of more than one; and into that assembly either every man hath right to enter, or not every one, but certain men distinguished from the rest; it is manifest there can be but three kinds of Commonwealth. For the representative must needs be one man, or more; and if more, then it is the assembly of all, or but of a part. When the representative is one man, then is the Commonwealth a monarchy; when an assembly of all that will come together, then it is a democracy, or popular Commonwealth; when an assembly of a part only, then it is called an aristocracy.And only three:

Other kind of Commonwealth there can be none: for either one, or more, or all, must have the sovereign power (which I have shown to be indivisible) entire. There be other names of government in the histories and books of policy; as tyranny and oligarchy; but they are not the names of other forms of government, but of the same forms misliked. For they that are discontented under monarchy call it tyranny; and they that are displeased with aristocracy call it oligarchy: so also, they which find themselves grieved under a democracy call it anarchy, which signifies want of government; and yet I think no man believes that want of government is any new kind of government: nor by the same reason ought they to believe that the government is of one kind when they like it, and another when they mislike it or are oppressed by the governors.And monarchy is the best, on practical grounds:

The difference between these three kinds of Commonwealth consisteth not in the difference of power, but in the difference of convenience or aptitude to produce the peace and security of the people; for which end they were instituted. And to compare monarchy with the other two, we may observe: first, that whosoever beareth the person of the people, or is one of that assembly that bears it, beareth also his own natural person. And though he be careful in his politic person to procure the common interest, yet he is more, or no less, careful to procure the private good of himself, his family, kindred and friends; and for the most part, if the public interest chance to cross the private, he prefers the private: for the passions of men are commonly more potent than their reason. From whence it follows that where the public and private interest are most closely united, there is the public most advanced. Now in monarchy the private interest is the same with the public. The riches, power, and honour of a monarch arise only from the riches, strength, and reputation of his subjects. For no king can be rich, nor glorious, nor secure, whose subjects are either poor, or contemptible, or too weak through want, or dissension, to maintain a war against their enemies; whereas in a democracy, or aristocracy, the public prosperity confers not so much to the private fortune of one that is corrupt, or ambitious, as doth many times a perfidious advice, a treacherous action, or a civil war.

Succession[edit]

The right of succession always lies with the sovereign. Democracies and aristocracies have easy succession; monarchy is harder:The greatest difficulty about the right of succession is in monarchy:

and the difficulty ariseth from this, that at first sight, it is not manifest who is to appoint the successor; nor many times who it is whom he hath appointed. For in both these cases, there is required a more exact ratiocination than every man is accustomed to use.Because in general people haven't thought carefully. However, the succession is definitely in the gift of the monarch:

As to the question who shall appoint the successor of a monarch that hath the sovereign authority... we are to consider that either he that is in possession has right to dispose of the succession, or else that right is again in the dissolved multitude. ... Therefore it is manifest that by the institution of monarchy, the disposing of the successor is always left to the judgement and will of the present possessor.But, it is not always obvious who the monarch has appointed:

And for the question which may arise sometimes, who it is that the monarch in possession hath designed to the succession and inheritance of his powerHowever, the answer is:

it is determined by his express words and testament; or by other tacit signs sufficient.And this means:

By express words, or testament, when it is declared by him in his lifetime, viva voce, or by writing; as the first emperors of Rome declared who should be their heirs.Note that (perhaps rather radically) this does not have to be any blood relative:

For the word heir does not of itself imply the children or nearest kindred of a man; but whomsoever a man shall any way declare he would have to succeed him in his estate. If therefore a monarch declare expressly that such a man shall be his heir, either by word or writing, then is that man immediately after the decease of his predecessor invested in the right of being monarch.However, practically this means:

But where testament and express words are wanting, other natural signs of the will are to be followed: whereof the one is custom. And therefore where the custom is that the next of kindred absolutely succeedeth, there also the next of kindred hath right to the succession; for that, if the will of him that was in possession had been otherwise, he might easily have declared the same in his lifetime...

Religion

In Leviathan, Hobbes explicitly states that the sovereign has authority to assert power over matters of faith and doctrine, and that if he does not do so, he invites discord. Hobbes presents his own religious theory, but states that he would defer to the will of the sovereign (when that was re-established: again, Leviathan was written during the Civil War) as to whether his theory was acceptable. Tuck argues that it further marks Hobbes as a supporter of the religious policy of the post-Civil War English republic, Independency.[citation needed]Taxation

Thomas Hobbes also touched upon the sovereign's ability to tax in Leviathan, although he is not as widely cited for his economic theories as he is for his political theories.[5] Hobbes believed that equal justice includes the equal imposition of taxes. The equality of taxes doesn’t depend on equality of wealth, but on the equality of the debt that every man owes to the commonwealth for his defence and the maintenance of the rule of law.[6] Hobbes also supported public support for those unable to maintain themselves by labour, which would presumably be funded by taxation. He advocated public encouragement of works of Navigation etc. to usefully employ the poor who could work.Part III: Of a Christian Common-wealth

In Part III Hobbes seeks to investigate the nature of a Christian commonwealth. This immediately raises the question of which scriptures we should trust, and why. If any person may claim supernatural revelation superior to the civil law, then there would be chaos, and Hobbes' fervent desire is to avoid this. Hobbes thus begins by establishing that we cannot infallibly know another's personal word to be divine revelation:When God speaketh to man, it must be either immediately or by mediation of another man, to whom He had formerly spoken by Himself immediately. How God speaketh to a man immediately may be understood by those well enough to whom He hath so spoken; but how the same should be understood by another is hard, if not impossible, to know. For if a man pretend to me that God hath spoken to him supernaturally, and immediately, and I make doubt of it, I cannot easily perceive what argument he can produce to oblige me to believe it.This is good, but if applied too fervently would lead to all the Bible being rejected. So, Hobbes says, we need a test: and the true test is established by examining the books of scripture, and is:

So that it is manifest that the teaching of the religion which God hath established, and the showing of a present miracle, joined together, were the only marks whereby the Scripture would have a true prophet,that is to say, immediate revelation, to be acknowledged; of them being singly sufficient to oblige any other man to regard what he saith.

Seeing therefore miracles now cease, we have no sign left whereby to acknowledge the pretended revelations or inspirations of any private man; nor obligation to give ear to any doctrine, farther than it is conformable to the Holy Scriptures, which since the time of our Saviour supply the place and sufficiently recompense the want of all other prophecy"Seeing therefore miracles now cease" means that only the books of the Bible can be trusted. Hobbes then discusses the various books which are accepted by various sects, and the "question much disputed between the diverse sects of Christian religion, from whence the Scriptures derive their authority". To Hobbes, "it is manifest that none can know they are God's word (though all true Christians believe it) but those to whom God Himself hath revealed it supernaturally". And therefore "The question truly stated is: by what authority they are made law?"

Unsurprisingly, Hobbes concludes that ultimately there is no way to determine this other than the civil power:

He therefore to whom God hath not supernaturally revealed that they are His, nor that those that published them were sent by Him, is not obliged to obey them by any authority but his whose commands have already the force of laws; that is to say, by any other authority than that of the Commonwealth, residing in the sovereign, who only has the legislative power.He discusses the Ten Commandments, and asks "who it was that gave to these written tables the obligatory force of laws. There is no doubt but they were made laws by God Himself: but because a law obliges not, nor is law to any but to them that acknowledge it to be the act of the sovereign, how could the people of Israel, that were forbidden to approach the mountain to hear what God said to Moses, be obliged to obedience to all those laws which Moses propounded to them?" and concludes, as before, that "making of the Scripture law, belonged to the civil sovereign."

Finally: "We are to consider now what office in the Church those persons have who, being civil sovereigns, have embraced also the Christian faith?" to which the answer is: "Christian kings are still the supreme pastors of their people, and have power to ordain what pastors they please, to teach the Church, that is, to teach the people committed to their charge."

There is an enormous amount of biblical scholarship in this third part. However, once Hobbes' initial argument is accepted (that no-one can know for sure anyone else's divine revelation) his conclusion (the religious power is subordinate to the civil) follows from his logic. The very extensive discussions of the chapter were probably necessary for its time. The need (as Hobbes saw it) for the civil sovereign to be supreme arose partly from the many sects that arose around the civil war, and to quash the Pope of Rome's challenge, to which Hobbes devotes an extensive section.

Part IV: Of the Kingdom of Darkness

Hobbes named Part IV of his book Kingdom of Darkness. By this, Hobbes does not mean Hell (he did not believe in Hell or Purgatory)[7] but the darkness of ignorance as opposed to the light of true knowledge. Hobbes' interpretation is largely unorthodox and so sees much darkness in what he sees as the misinterpretation of Scripture.- This considered, the kingdom of darkness... is nothing else but a confederacy of deceivers that, to obtain dominion over men in this present world, endeavour, by dark and erroneous doctrines, to extinguish in them the light...[8]

The first is by extinguishing the light of scripture through misinterpretation. Hobbes sees the main abuse as teaching that the kingdom of God can be found in the church, thus undermining the authority of the civil sovereign. Another general abuse of scripture, in his view, is the turning of consecration into conjuration, or silly ritual.

The second cause is the demonology of the heathen poets concerning demons, which in Hobbes opinion are nothing more than constructs of the brain. Hobbes then goes on to criticize what he sees as many of the practices of Catholicism: "Now for the worship of saints, and images, and relics, and other things at this day practiced in the Church of Rome, I say they are not allowed by the word of God".

The third is by mixing with the Scripture diverse relics of the religion, and much of the vain and erroneous philosophy of the Greeks, especially of Aristotle. Hobbes has little time for the various disputing sects of philosophers and objects to what people have taken "From Aristotle's civil philosophy, they have learned to call all manner of Commonwealths but the popular (such as was at that time the state of Athens), tyranny". At the end of this comes an interesting section (darkness is suppressing true knowledge as well as introducing falsehoods), which would appear to bear on the discoveries of Galileo Galilei. "Our own navigation's make manifest, and all men learned in human sciences now acknowledge, there are antipodes" (i.e., the Earth is round) "...Nevertheless, men... have been punished for it by authority ecclesiastical. But what reason is there for it? Is it because such opinions are contrary to true religion? That cannot be, if they be true." However, Hobbes is quite happy for the truth to be suppressed if necessary: if "they tend to disorder in government, as countenancing rebellion or sedition? Then let them be silenced, and the teachers punished" – but only by the civil authority.

The fourth is by mingling with both these, false or uncertain traditions, and feigned or uncertain history.

Hobbes finishes by inquiring who benefits from the errors he diagnoses:

- Cicero maketh honourable mention of one of the Cassii, a severe judge amongst the Romans, for a custom he had in criminal causes, when the testimony of the witnesses was not sufficient, to ask the accusers, cui bono; that is to say, what profit, honour, or other contentment the accused obtained or expected by the fact. For amongst presumptions, there is none that so evidently declareth the author as doth the benefit of the action.