From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In paleoanthropology, the recent African origin of modern humans, or the "out of Africa" theory (OOA), is the most widely accepted model of the geographic origin and early migration of anatomically modern humans. The theory is called the "out-of-Africa" theory in the popular press, and the "recent single-origin hypothesis" (RSOH), "replacement hypothesis", or "recent African origin model" (RAO) by experts in the field. The concept was speculative before it was corroborated in the 1980s by a study of present-day mitochondrial DNA, combined with evidence based on physical anthropology of archaic specimens.

Genetic studies and fossil evidence show that archaic Homo sapiens evolved to anatomically modern humans solely in Africa between 200,000 and 60,000 years ago,[1] that members of one branch of Homo sapiens left Africa at some point between 125,000 and 60,000 years ago, and that over time these humans replaced more primitive populations of the genus Homo such as Neanderthals and Homo erectus.[2] The date of the earliest successful "out of Africa" migration (earliest migrants with living descendants) has generally been placed at 60,000 years ago based on genetics, but migration out of the continent may have taken place as early as 125,000 years ago according to Arabian archaeological finds of tools in the region.[3]

The recent single origin of modern humans in East Africa is the predominant position held within the scientific community.[4][5][6][7][8] There are differing theories on whether there was a single exodus or several. A growing number of researchers also suspect that "long-neglected North Africa" was the original home of the modern humans who first trekked out of the continent.[9][10][11]

The major competing hypothesis is the multiregional origin of modern humans, which envisions a wave of Homo sapiens migrating earlier from Africa and interbreeding with local Homo erectus populations in multiple regions of the globe. Most multiregionalists still view Africa as a major wellspring of human genetic diversity, but allow a much greater role for hybridization.[12][13]

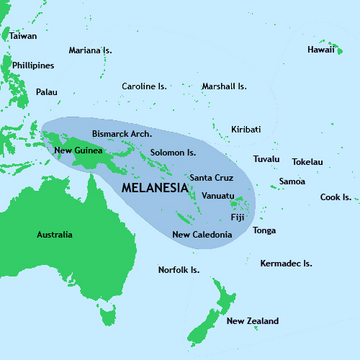

Genetic testing in the last decade has revealed that several now extinct archaic human species may have interbred with modern humans. These species have been claimed to have left their genetic imprint in different regions across the world: Neanderthals in all humans except Sub-Saharan Africans, Denisova hominin in Australasia (for example, Melanesians, Aboriginal Australians and some Negritos) and there could also have been interbreeding between Sub-Saharan Africans and an as-yet-unknown hominin (possibly remnants of the ancient species Homo heidelbergensis). However, the rate of interbreeding was found to be relatively low (1-10%) and other studies have suggested that the presence of Neanderthal or other archaic human genetic markers in modern humans can be attributed to shared ancestral traits originating from a common ancestor 500,000 to 800,000 years ago.[14][15][16][17][18]

History of the theory

With the development of anthropology in the early 19th century, scholars disagreed vigorously about different theories of human development. Those such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach and James Cowles Prichard held that since the creation, the various human races had developed as different varieties sharing descent from one people (monogenism). Their opponents, such as Louis Agassiz and Josiah C. Nott, argued for polygenism, or the separate development of human races as separate species or had developed as separate species through transmutation of species from apes, with no common ancestor.

The frontispiece to Huxley's Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature (1863): the image compares the skeletons of apes to humans.

Charles Darwin was one of the first to propose common descent of living organisms, and among the first to suggest that all humans had in common ancestors who lived in Africa.[19] Darwin first suggested the "Out of Africa" hypothesis after studying the behaviour of African apes, one of which was displayed at the London Zoo. The anatomist Thomas Huxley had also supported the hypothesis and suggested that African apes have a close evolutionary relationship with humans.[20] These views were however opposed by Ernst Haeckel the German biologist who was a proponent of the Out of Asia theory. Haeckel argued that humans were more closely related to the primates of Southeast Asia and rejected Darwin’s hypothesis of Africa.[21][22]

In the Descent of Man, Darwin speculated that humans had descended from apes which still had small brains but walked upright, freeing their hands for uses which favoured intelligence. Further, he thought such apes were African:[23]

In each great region of the world the living mammals are closely related to the extinct species of the same region. It is, therefore, probable that Africa was formerly inhabited by extinct apes closely allied to the gorilla and chimpanzee; and as these two species are now man's nearest allies, it is somewhat more probable that our early progenitors lived on the African continent than elsewhere. But it is useless to speculate on this subject, for an ape nearly as large as a man, namely the Dryopithecus of Lartet, which was closely allied to the anthropomorphous Hylobates, existed in Europe during the Upper Miocene period; and since so remote a period the earth has certainly undergone many great revolutions, and there has been ample time for migration on the largest scale.The prediction was insightful, because in 1871 there were hardly any human fossils of ancient hominids available. Almost fifty years later, Darwin's speculation was supported when anthropologists began finding numerous fossils of ancient small-brained hominids in several areas of Africa (list of hominina fossils).

—Charles Darwin, Descent of Man[24]

The debate in anthropology had swung in favour of monogenism by the mid-20th century. Isolated proponents of polygenism held forth in the mid-20th century, such as Carleton Coon, who hypothesized as late as 1962 that Homo sapiens arose five times from Homo erectus in five places.[25] The "Recent African origin" of modern humans means "single origin" (monogenism) and has been used in various contexts as an antonym to polygenism.

In the 1980s Allan Wilson together with Rebecca L. Cann and Mark Stoneking worked on the so-called "Mitochondrial Eve" hypothesis. In his efforts to identify informative genetic markers for tracking human evolutionary history, he started to focus on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) – genes that sit in the cell, but not in the nucleus, and are passed from mother to child. This DNA material is important because it mutates quickly, thus making it easy to plot changes over relatively short time spans. By comparing differences in the mtDNA Wilson believed it was possible to estimate the time, and the place, modern humans first evolved. With his discovery that human mtDNA is genetically much less diverse than chimpanzee mtDNA, he concluded that modern human populations had diverged recently from a single population while older human species such as Neandertals and Homo erectus had become extinct. He and his team compared mtDNA in people of different ancestral backgrounds and concluded that all modern humans evolved from one 'lucky mother' in Africa about 150,000 years ago.[26] With the advent of archaeogenetics in the 1990s, scientists were able to date the "out of Africa" migration with some confidence.

In 2000, the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequence of "Mungo Man 3" (LM3) of ancient Australia was published indicating that Mungo Man was an extinct subspecies that diverged before the most recent common ancestor of contemporary humans. The results, if correct, supports the multiregional origin of modern humans hypothesis.[27][28] This work was later questioned[29][30] and explained by W. James Peacock, leader of the team who sequenced Mungo man's aDNA.[31] In addition, a large-scale genotyping analysis of aboriginal Australians, New Guineans, Southeast Asians and Indians in 2013 showed close genetic relationship between Australian, New Guinean, and the Mamanwa people, with divergence times for these groups estimated at 36,000 y ago. Further, substantial gene flow was detected between the Indian populations and aboriginal Australians, indicating an early "southern route" migration out of Africa, and arrival of other populations in the region by subsequent dispersal. This basically opposes the view that there was an isolated human evolution in Australia.[32]

The question of whether there was inheritance of other typological (not de facto) Homo subspecies into the Homo sapiens genetic pool is debated.

Early Homo sapiens

Anatomical comparison of the skulls of a modern human (left) and Homo neanderthalensis (right).

Anatomically modern humans originated in Africa about 250,000 years ago. The trend in cranial expansion and the acheulean elaboration of stone tool technologies which occurred between 400,000 years ago and the second interglacial period in the Middle Pleistocene (around 250,000 years ago) provide evidence for a transition from H. erectus to H. sapiens.[33] In the Recent African Origin (RAO) scenario, migration within and out of Africa eventually replaced the earlier dispersed H. erectus.

Homo sapiens idaltu, found at site Middle Awash in Ethiopia, lived about 160,000 years ago.[34] It is the oldest known anatomically modern human and classified as an extinct subspecies.[35] Fossils of early Homo sapiens were found in Qafzeh cave in Israel and have been dated to 80,000 to 100,000 years ago. However these humans seem to have either become extinct or retreated back to Africa 70,000 to 80,000 years ago, possibly replaced by south bound Neanderthals escaping the colder regions of ice age Europe.[36] Hua Liu et al. analyzed autosomal microsatellite markers dates to c. 56,000±5,700 years ago mtDNA evidence. He interprets the paleontological fossil of early modern human from Qafzeh cave as an isolated early offshoot that retracted back to Africa.[37]

All other fossils of fully modern humans outside Africa have been dated to more recent times. The oldest well dated fossil of modern humans found outside Africa is from Manot Cave in Israel, named Manot 1, which have been dated to 54,700 years ago.[38][39] Fossils from Lake Mungo, Australia have been dated to about 42,000 years ago.[40][41] The Tianyuan cave remains in Liujiang region China have a probable date range between 38,000 and 42,000 years ago. They are most similar in morphology to Minatogawa Man, modern humans dated between 17,000 and 19,000 years ago and found on Okinawa Island, Japan.[42][43] However, others have dated Liujang Man to 111,000 to 139,000 years before the present.[44]

Beginning about 100,000 years ago evidence of more sophisticated technology and artwork begins to emerge and by 50,000 years ago fully modern behaviour becomes more prominent. Stone tools show regular patterns that are reproduced or duplicated with more precision while tools made of bone and antler appear for the first time.[45][46]

Genetic reconstruction

Two pieces of the human genome are quite useful in deciphering human history: mitochondrial DNA and the Y chromosome. These are the only two parts of the genome that are not shuffled about by the evolutionary mechanisms that generate diversity with each generation: instead, these elements are passed down intact. According to the hypothesis, all people alive today have inherited the same mitochondria[47] from a woman who lived in Africa about 160,000 years ago.[48][49] She has been named Mitochondrial Eve. All men living today have inherited their Y chromosomes from a man who lived 140,000–500,000 years ago, probably in Africa. He has been named Y-chromosomal Adam. Based on comparisons of non-sex-specific chromosomes with sex-specific ones, it is now believed that more men than women participated in the out-of-Africa exodus of early humans.[50]Mitochondrial DNA

Map of early diversification of modern humans according to mitochondrial population genetics (see: Haplogroup L).

The first lineage to branch off from Mitochondrial Eve is L0. This haplogroup is found in high proportions among the San of Southern Africa, the Sandawe of East Africa. It is also found among the Mbuti people.[51][52]

These groups branched off early in human history and have remained relatively genetically isolated since then. Haplogroups L1, L2 and L3 are descendents of L1-6 and are largely confined to Africa. The macro haplogroups M and N, which are the lineages of the rest of the world outside Africa, descend from L3. L3 is about 84,000 years old, and haplogroup M and N are almost identical in age at about 63,000 years old. [53]

Genomic analysis

Although mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosomal DNA are particularly useful in deciphering human history, data on the genomes of dozens of population groups have also been studied. In June 2009, an analysis of genome-wide SNP data from the International HapMap Project (Phase II) and CEPH Human Genome Diversity Panel samples was published.[54] Those samples were taken from 1138 unrelated individuals.[54] Before this analysis, population geneticists expected to find dramatic differences among ethnic groups, with derived alleles shared among such groups but uncommon or nonexistent in other groups.[55] Instead the study of 53 populations taken from the HapMap and CEPH data revealed that the population groups studied fell into just three genetic groups: Africans, Eurasians (which includes natives of Europe and the Middle East, and Southwest Asians east to present-day Pakistan), and East Asians, which includes natives of Asia, Japan, Southeast Asia, the Americas, and Oceania.[55]The study determined that most ethnic group differences can be attributed to genetic drift, with modern African populations having greater genetic diversity than the other two genetic groups, and modern Eurasians somewhat more than modern East Asians.[55] The study suggested that natural selection may shape the human genome much more slowly than previously thought, with factors such as migration within and among continents more heavily influencing the distribution of genetic variations.[56] A May 2002 study examined three groups, African, European, and Asian. It found greater genetic diversity among Africans than among Eurasians, and that genetic diversity among Eurasians is largely a subset of that among Africans, supporting the 'out of Africa' model.[57]

Movement out of Africa

By some 70,000 years ago, a part of the bearers of mitochondrial haplogroup L3 migrated from East Africa into the Near East. The date of this first wave of "out of Africa" migration was called into question in 2011, based on the discovery of stone tools in the United Arab Emirates, indicating the presence of modern humans between 100,000 and 125,000 years ago.[3][58] New research showing slower than previously thought genetic mutations in human DNA published in 2012, indicating a revised dating for the migration of between 90,000 and 130,000 years ago.[59]

Some scientists believe that only a few people left Africa in a single migration that went on to populate the rest of the world,[60] based in the fact that only descendents of L3 are found outside Africa. From that settlement, some others point to the possibility of several waves of expansion. For example, geneticist Spencer Wells says that the early travellers followed the southern coastline of Asia, crossed about 250 kilometres (155 mi) of sea, and colonized Australia by around 50,000 years ago. The Aborigines of Australia, Wells says, are the descendants of the first wave of migrations.[61]

It has been estimated that from a population of 2,000 to 5,000 individuals in Africa,[62] only a small group, possibly as few as 150 to 1,000 people, crossed the Red Sea.[63] Of all the lineages present in Africa only the female descendants of one lineage, mtDNA haplogroup L3, are found outside Africa. If there had been several migrations, one would expect descendants of more than one lineage to be found outside Africa. L3's female descendants, the M and N haplogroup lineages, are found in very low frequencies in Africa (although haplogroup M1 populations are very ancient and diversified in North and Northeast Africa) and appear to be more recent arrivals. A possible explanation is that these mutations occurred in East Africa shortly before the exodus and became the dominant haplogroups after the exodus from Africa through the founder effect. Alternatively, the mutations may have arisen shortly after the exodus from Africa.

Other scientists have proposed a multiple dispersal model according to which there were two migrations out of Africa, one across the Red Sea and along the coastal regions to India (the coastal route), which would be represented by haplogroup M. Another group of migrants with haplogroup N followed the Nile from East Africa, heading northwards and crossing into Asia through the Sinai. This group then branched in several directions, some moving into Europe and others heading east into Asia. This hypothesis is supported by the relatively late date of the arrival of modern humans in Europe as well as by both archaeological and DNA evidence. Results from mtDNA collected from aboriginal Malaysians called Orang Asli and the creation of a phylogentic tree indicate that the hapologroups M and N share characteristics with original African groups from approximately 85,000 years ago and share characteristics with sub-haplogroups among coastal southeast Asian regions, such as Australasia, the Indian Subcontinent, and throughout continental Asia, which had dispersed and separated from its African origins approximately 65,000 years ago. This southern coastal dispersion would have occurred before the original theory of dispersion through the Levant approximately 45,000 years ago.[64] This hypothesis attempts to explain why haplogroup N is predominant in Europe and why haplogroup M is absent in Europe. Evidence of the coastal migration is hypothesized to have been destroyed by the rise in sea levels during the Holocene epoch.[65][66] Alternatively, a small European founder population that initially expressed both haplogroup M and N could have lost haplogroup M through random genetic drift resulting from a bottleneck (i.e. a founder effect).

Today at the Bab-el-Mandeb straits, the Red Sea is about 20 kilometres (12 mi) wide, but 50,000 years ago sea levels were 70 m (230 ft) lower (owing to glaciation) and the water was much narrower. Though the straits were never completely closed, they were narrow enough and there may have been islands in between to have enabled crossing using simple rafts.[67][68] Shell middens 125,000 years old have been found in Eritrea,[69] indicating the diet of early humans included seafood obtained by beachcombing.

Subsequent expansion

From the Near East, these populations spread east to South Asia by 50,000 years ago, and on to Australia by 40,000 years ago, Homo sapiens for the first time colonizing territory never reached by Homo erectus. Europe was reached by Cro-Magnon some 40,000 years ago. East Asia (Korea, Japan) was reached by 30,000 years ago. It is disputed whether subsequent migration to North America took place around 30,000 years ago, or only considerably later, around 14,000 years ago.[71]

The group that crossed the Red Sea travelled along the coastal route around the coast of Arabia and Persia until reaching India, which appears to be the first major settling point. Haplogroup M is found in high frequencies along the southern coastal regions of Pakistan and India and it has the greatest diversity in India, indicating that it is here where the mutation may have occurred.[72] Sixty percent of the Indian population belong to Haplogroup M.

The indigenous people of the Andaman Islands also belong to the M lineage. The Andamanese are thought to be offshoots of some of the earliest inhabitants in Asia because of their long isolation from mainland Asia. They are evidence of the coastal route of early settlers that extends from India along the coasts of Thailand and Indonesia all the way to Papua New Guinea. Since M is found in high frequencies in highlanders from New Guinea as well, and both the Andamanese and New Guineans have dark skin and Afro-textured hair, some scientists believe they are all part of the same wave of migrants who departed across the Red Sea ~60,000 years ago in the Great Coastal Migration.

Notably, the findings of Harding et al.[73] show that, at least with regard to dark skin color, the haplotype background of Papua New Guineans at MC1R (one of a number of genes involved in melanin production) is identical to that of Africans (barring a single silent mutation). Thus, although these groups are distinct from Africans at other loci (due to drift, bottlenecks, etc.), it is evident that selection for the dark skin color trait likely continued (at least at MC1R) following the exodus. This would support the hypothesis that suggests that the original migrants from Africa resembled pre-exodus Africans (at least in skin color), and that the present day remnants of this ancient phenotype can be seen among contemporary Africans, Andamanese and New Guineans. Others suggest that their physical resemblance to Africans could be the result of convergent evolution.[74][75]

From Arabia to India the proportion of haplogroup M increases eastwards: in eastern India, M outnumbers N by a ratio of 3:1. However, crossing over into East Asia, Haplogroup N reappears as the dominant lineage. M is predominant in South East Asia but amongst Indigenous Australians N reemerges as the more common lineage. This discontinuous distribution of Haplogroup N from Europe to Australia can be explained by founder effects and population bottlenecks.[76] In addition to genetic analysis, Petraglia et al. also examines the microlithic materials from Indian subcontinent and explains the expansion of population based on the reconstruction of paleoenvironment. He proposed that microlithic industries could be traced back to 35ka in South Asia, and the new technology might be influenced by environmental change and population pressure.[77]