From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Robert Frost | |

|---|---|

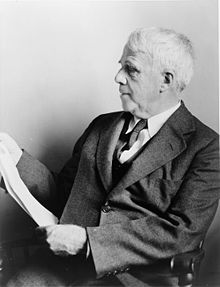

Robert Frost (1941)

|

|

| Born | Robert Lee Frost March 26, 1874 San Francisco, California, US |

| Died | January 29, 1963 (aged 88) Boston, Massachusetts, US |

| Occupation | Poet, playwright |

| Notable works | A Boy's Will, North of Boston[1] |

| Notable awards | Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, Congressional Gold Medal, |

| Spouse | Elinor Miriam White (1895–1938) |

| Children |

|

| Signature | |

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 – January 29, 1963) was an American poet. His work was initially published in England before it was published in America. He is highly regarded for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloquial speech.[2] His work frequently employed settings from rural life in New England in the early twentieth century, using them to examine complex social and philosophical themes. One of the most popular and critically respected American poets of the twentieth century,[3] Frost was honored frequently during his lifetime, receiving four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. He became one of America's rare "public literary figures, almost an artistic institution." [3] He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1960 for his poetical works. On July 22, 1961, Frost was named Poet laureate of Vermont.

Biography

Early years

Robert Frost was born in San Francisco, California, to journalist William Prescott Frost, Jr., and Isabelle Moodie.[2] His mother was of Scottish descent, and his father descended from Nicholas Frost of Tiverton, Devon, England, who had sailed to New Hampshire in 1634 on the Wolfrana.

Frost's father was a teacher and later an editor of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin (which later merged with The San Francisco Examiner), and an unsuccessful candidate for city tax collector. After his death on May 5, 1885, the family moved across the country to Lawrence, Massachusetts, under the patronage of (Robert's grandfather) William Frost, Sr., who was an overseer at a New England mill. Frost graduated from Lawrence High School in 1892.[4] Frost's mother joined the Swedenborgian church and had him baptized in it, but he left it as an adult.

Although known for his later association with rural life, Frost grew up in the city, and he published his first poem in his high school's magazine. He attended Dartmouth College for two months, long enough to be accepted into the Theta Delta Chi fraternity. Frost returned home to teach and to work at various jobs, including helping his mother teach her class of unruly boys, delivering newspapers, and working in a factory maintaining carbon arc lamps. He did not enjoy these jobs, feeling his true calling was poetry.

Adult years

In 1894 he sold his first poem, "My Butterfly. An Elegy" (published in the November 8, 1894, edition of the New York Independent) for $15 ($409 today). Proud of his accomplishment, he proposed marriage to Elinor Miriam White, but she demurred, wanting to finish college (at St. Lawrence University) before they married. Frost then went on an excursion to the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia and asked Elinor again upon his return. Having graduated, she agreed, and they were married at Lawrence, Massachusetts on December 19, 1895.

Frost attended Harvard University from 1897 to 1899, but he left voluntarily due to illness.[5][6][7] Shortly before his death, Frost's grandfather purchased a farm for Robert and Elinor in Derry, New Hampshire; Frost worked the farm for nine years while writing early in the mornings and producing many of the poems that would later become famous. Ultimately his farming proved unsuccessful and he returned to the field of education as an English teacher at New Hampshire's Pinkerton Academy from 1906 to 1911, then at the New Hampshire Normal School (now Plymouth State University) in Plymouth, New Hampshire.

In 1912 Frost sailed with his family to Great Britain, settling first in Beaconsfield, a small town outside London. His first book of poetry, A Boy's Will, was published the next year. In England he made some important acquaintances, including Edward Thomas (a member of the group known as the Dymock poets), T. E. Hulme, and Ezra Pound. Although Pound would become the first American to write a favorable review of Frost's work, Frost later resented Pound's attempts to manipulate his American prosody. Frost met or befriended many contemporary poets in England, especially after his first two poetry volumes were published in London in 1913 (A Boy's Will) and 1914 (North of Boston).

The Robert Frost Farm in Derry, New Hampshire, where he wrote many of his poems, including "Tree at My Window" and "Mending Wall."

As World War I began, Frost returned to America in 1915 and bought a farm in Franconia, New Hampshire, where he launched a career of writing, teaching and lecturing. This family homestead served as the Frosts' summer home until 1938. It is maintained today as The Frost Place, a museum and poetry conference site. During the years 1916–20, 1923–24, and 1927–1938, Frost taught English at Amherst College in Massachusetts, notably encouraging his students to account for the myriad sounds and intonations of the spoken English language in their writing. He called his colloquial approach to language "the sound of sense."[8]

In 1924, he won the first of four Pulitzer Prizes for the book New Hampshire: A Poem with Notes and Grace Notes. He would win additional Pulitzers for Collected Poems in 1931, A Further Range in 1937, and A Witness Tree in 1943.[9]

For forty-two years — from 1921 to 1963 — Frost spent almost every summer and fall teaching at the Bread Loaf School of English of Middlebury College, at its mountain campus at Ripton, Vermont. He is credited as a major influence upon the development of the school and its writing programs. The college now owns and maintains his former Ripton farmstead as a national historic site near the Bread Loaf campus. In 1921 Frost accepted a fellowship teaching post at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, where he resided until 1927 when he returned to teach at Amherst. While teaching at the University of Michigan, he was awarded a lifetime appointment at the University as a Fellow in Letters.[10] The Robert Frost Ann Arbor home was purchased by The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan and relocated to the museum's Greenfield Village site for public tours.

In 1940 he bought a 5-acre (2.0 ha) plot in South Miami, Florida, naming it Pencil Pines; he spent his winters there for the rest of his life.[11] His properties also included a house on Brewster Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that today belongs to the National Historic Register.

Harvard's 1965 alumni directory indicates Frost received an honorary degree there. Although he never graduated from college, Frost received over 40 honorary degrees, including ones from Princeton, Oxford and Cambridge universities, and was the only person to receive two honorary degrees from Dartmouth College. During his lifetime, the Robert Frost Middle School in Fairfax, Virginia, the Robert L. Frost School in Lawrence, Massachusetts, and the main library of Amherst College were named after him.

In 1960, was awarded a United States Congressional Gold Medal, "In recognition of his poetry, which has enriched the culture of the United States and the philosophy of the world,"[12] which was finally bestowed by President Kennedy in March 1962.[13]

Frost was 86 when he read his well-known poem "The Gift Outright" at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy on January 20, 1961. He died in Boston two years later, on January 29, 1963, of complications from prostate surgery. He was buried at the Old Bennington Cemetery in Bennington, Vermont. His epitaph quotes the last line from his poem, "The Lesson for Today (1942): "I had a lover's quarrel with the world."

One of the original collections of Frost materials, to which he himself contributed, is found in the Special Collections department of the Jones Library in Amherst, Massachusetts. The collection consists of approximately twelve thousand items, including original manuscript poems and letters, correspondence and photographs, as well as audio and visual recordings.[14] The Archives and Special Collections at Amherst College holds a small collection of his papers. The most significant collection of Frost's working manuscripts is held by Dartmouth.

Personal life

Robert Frost's personal life was plagued with grief and loss. In 1885 when Frost was 11, his father died of tuberculosis, leaving the family with just eight dollars. Frost's mother died of cancer in 1900. In 1920, Frost had to commit his younger sister Jeanie to a mental hospital, where she died nine years later. Mental illness apparently ran in Frost's family, as both he and his mother suffered from depression, and his daughter Irma was committed to a mental hospital in 1947. Frost's wife, Elinor, also experienced bouts of depression.[10]

Elinor and Robert Frost had six children: son Elliot (1896–1904, died of cholera); daughter Lesley Frost Ballantine (1899–1983); son Carol (1902–1940, committed suicide); daughter Irma (1903–1967); daughter Marjorie (1905–1934, died as a result of puerperal fever after childbirth); and daughter Elinor Bettina (died just three days after her birth in 1907). Only Lesley and Irma outlived their father. Frost's wife, who had heart problems throughout her life, developed breast cancer in 1937, and died of heart failure in 1938.[10]

Work

Style and critical response

The poet/critic Randall Jarrell often praised Frost's poetry and wrote, "Robert Frost, along with Stevens and Eliot, seems to me the greatest of the American poets of this century. Frost's virtues are extraordinary. No other living poet has written so well about the actions of ordinary men; his wonderful dramatic monologues or dramatic scenes come out of a knowledge of people that few poets have had, and they are written in a verse that uses, sometimes with absolute mastery, the rhythms of actual speech." He also praised "Frost's seriousness and honesty," stating that Frost was particularly skilled at representing a wide range of human experience in his poems.[15]Jarrell's notable and influential essays on Frost include the essays "Robert Frost's 'Home Burial'" (1962), which consisted of an extended close reading of that particular poem, and "To The Laodiceans" (1952) in which Jarrell defended Frost against critics who had accused Frost of being too "traditional" and out of touch with Modern or Modernist poetry.

In Frost's defense, Jarrell wrote "the regular ways of looking at Frost's poetry are grotesque simplifications, distortions, falsifications—coming to know his poetry well ought to be enough, in itself, to dispel any of them, and to make plain the necessity of finding some other way of talking about his work." And Jarrell's close readings of poems like "Neither Out Too Far Nor In Too Deep" led readers and critics to perceive more of the complexities in Frost's poetry.[16][17]

In an introduction to Jarrell's book of essays, Brad Leithauser notes that, "the 'other' Frost that Jarrell discerned behind the genial, homespun New England rustic—the 'dark' Frost who was desperate, frightened, and brave—has become the Frost we've all learned to recognize, and the little-known poems Jarrell singled out as central to the Frost canon are now to be found in most anthologies." [18][19]

Jarrell lists a selection of the Frost poems he considers the most masterful, including "The Witch of Coös," "Home Burial," "A Servant to Servants," "Directive," "Neither Out Too Far Nor In Too Deep," "Provide, Provide," "Acquainted with the Night," "After Apple Picking," "Mending Wall," "The Most of It," "An Old Man's Winter Night," "To Earthward," "Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening," "Spring Pools," "The Lovely Shall Be Choosers," "Design," [and] "Desert Places."[20]

From "Birches"[21]

I'd like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it and begin over.

May no fate willfully misunderstand me

And half grant what I wish and snatch me away

Not to return. Earth's the right place for love:

I don't know where it's likely to go better.

I'd like to go by climbing a birch tree,

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

And then come back to it and begin over.

May no fate willfully misunderstand me

And half grant what I wish and snatch me away

Not to return. Earth's the right place for love:

I don't know where it's likely to go better.

I'd like to go by climbing a birch tree,

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

Robert Frost

In 2003, the critic Charles McGrath noted that critical views on Frost's poetry have changed over the years (as has his public image). In an article called "The Vicissitudes of Literary Reputation," McGrath wrote, "Robert Frost ... at the time of his death in 1963 was generally considered to be a New England folkie ... In 1977, the third volume of Lawrance Thompson's biography suggested that Frost was a much nastier piece of work than anyone had imagined; a few years later, thanks to the reappraisal of critics like William H. Pritchard and Harold Bloom and of younger poets like Joseph Brodsky, he bounced back again, this time as a bleak and unforgiving modernist."[22]

In The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, editors Richard Ellmann and Robert O'Clair compared and contrasted Frost's unique style to the work of the poet Edwin Arlington Robinson since they both frequently used New England settings for their poems. However, they state that Frost's poetry was "less [consciously] literary" and that this was possibly due to the influence of English and Irish writers like Thomas Hardy and W.B. Yeats. They note that Frost's poems "show a successful striving for utter colloquialism" and always try to remain down to earth, while at the same time using traditional forms despite the trend of American poetry towards free verse which Frost famously said was "'like playing tennis without a net.'"[23]

In providing an overview of Frost's style, the Poetry Foundation makes the same point, placing Frost's work "at the crossroads of nineteenth-century American poetry [with regard to his use of traditional forms] and modernism [with his use of idiomatic language and ordinary, every day subject matter]." They also note that Frost believed that "the self-imposed restrictions of meter in form" was more helpful than harmful because he could focus on the content of his poems instead of concerning himself with creating "innovative" new verse forms.[24]

Themes

In Contemporary Literary Criticism, the editors state that "Frost's best work explores fundamental questions of existence, depicting with chilling starkness the loneliness of the individual in an indifferent universe."[25] The critic T. K. Whipple focused in on this bleakness in Frost's work, stating that "in much of his work, particularly in North of Boston, his harshest book, he emphasizes the dark background of life in rural New England, with its degeneration often sinking into total madness." [25]In sharp contrast, the founding publisher and editor of Poetry, Harriet Monroe, emphasized the folksy New England persona and characters in Frost's work, writing that "perhaps no other poet in our history has put the best of the Yankee spirit into a book so completely." [25] She notes his frequent use of rural settings and farm life, and she likes that in these poems, Frost is most interested in "showing the human reaction to nature's processes." She also notes that while Frost's narrative, character-based poems are often satirical, Frost always has a "sympathetic humor" towards his subjects.[25]

Pulitzer Prizes

- 1924 for New Hampshire: A Poem With Notes and Grace Notes

- 1931 for Collected Poems

- 1937 for A Further Range

- 1943 for A Witness Tree

Poet laureate of Vermont

In June 1922 the Vermont State League of Women's Clubs elected Frost as Poet laureate of Vermont. When a New York Times editorial strongly criticised the decision of the Women's Clubs, Sarah Cleghorn and other women wrote to the newspaper defending Frost.[26]On July 22, 1961 Frost was named Poet laureate of Vermont by the state legislature through Joint Resolution R-59 of the Acts of 1961, which also created the position.[27][28][29][30]

Selected works

Poetry collections

- A Boy's Will (David Nutt 1913;Holt, 1915)[31]

- North of Boston (David Nutt, 1914; Holt, 1914)

- "Birches"

- "Mending Wall"

- Mountain Interval (Holt, 1916)

- Selected Poems (Holt, 1923)

- Includes poems from first three volumes and the poem The Runaway

- New Hampshire (Holt, 1923; Grant Richards, 1924)

- Several Short Poems (Holt, 1924)[1]

- Selected Poems (Holt, 1928)

- West-Running Brook (Holt, 1928? 1929)

- The Lovely Shall Be Choosers, The Poetry Quartos, printed and illustrated by Paul Johnston (Random House, 1929)

- Collected Poems of Robert Frost (Holt, 1930; Longmans, Green, 1930)

- The Lone Striker (Knopf, 1933)

- Selected Poems: Third Edition (Holt, 1934)

- Three Poems (Baker Library, Dartmouth College, 1935)

- The Gold Hesperidee (Bibliophile Press, 1935)

- From Snow to Snow (Holt, 1936)

- A Further Range (Holt, 1936; Cape, 1937)

- Collected Poems of Robert Frost (Holt, 1939; Longmans, Green, 1939)

- A Witness Tree (Holt, 1942; Cape, 1943)

- Come In, and Other Poems (1943)

- Steeple Bush (Holt, 1947)

- Complete Poems of Robert Frost, 1949 (Holt, 1949; Cape, 1951)

- Hard Not To Be King (House of Books, 1951)

- Aforesaid (Holt, 1954)

- A Remembrance Collection of New Poems (Holt, 1959)

- You Come Too (Holt, 1959; Bodley Head, 1964)

- In the Clearing (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1962)

- The Poetry of Robert Frost (New York, 1969)

- A Further Range (published as Further Range in 1926, as New Poems by Holt, 1936; Cape, 1937)

- What Fifty Said

- Fire And Ice

- A Drumlin Woodchuck

Plays

- A Way Out: A One Act Play (Harbor Press, 1929).

- The Cow's in the Corn: A One Act Irish Play in Rhyme (Slide Mountain Press, 1929).

- A Masque of Reason (Holt, 1945).

- A Masque of Mercy (Holt, 1947).

Prose books

- The Letters of Robert Frost to Louis Untermeyer (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1963; Cape, 1964).

- Robert Frost and John Bartlett: The Record of a Friendship, by Margaret Bartlett Anderson (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1963).

- Selected Letters of Robert Frost (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1964).

- Interviews with Robert Frost (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1966; Cape, 1967).

- Family Letters of Robert and Elinor Frost (State University of New York Press, 1972).

- Robert Frost and Sidney Cox: Forty Years of Friendship (University Press of New England, 1981).

- The Notebooks of Robert Frost, edited by Robert Faggen (Harvard University Press, January 2007). [2]

Letters

- The Letters of Robert Frost, Volume 1, 1886–1921, edited by Donald Sheehy, Mark Richardson, and Robert Faggen (Harvard University Press; 2014); 811 pages; first volume of the scholarly edition of the poet's correspondence, including many previously unpublished letters.

Omnibus volumes

- Collected Poems, Prose and Plays (Richard Poirier, ed.) (Library of America, 1995) ISBN 978-1-883011-06-2.