A

season is a division of the

year, marked by changes in weather, ecology and hours of daylight. Seasons result from the yearly orbit of the

Earth around the

Sun and the

tilt of the Earth's rotational axis relative to the plane of the orbit.

[1][2] In temperate and polar regions, the seasons are marked by changes in the intensity of sunlight that reaches the Earth's surface, variations of which may cause animals to go into

hibernation or to migrate, and plants to be dormant.

During May, June, and July, the

northern hemisphere is exposed to more direct sunlight because the hemisphere faces the sun. The same is true of the

southern hemisphere in November, December, and January. It is the tilt of the Earth that causes the Sun to be higher in the sky during the summer

months which increases the

solar flux. However, due to

seasonal lag, June, July, and August are the hottest months in the northern hemisphere and December, January, and February are the hottest months in the southern hemisphere.

In

temperate and

subpolar regions, four

calendar-based seasons (with their adjectives) are generally recognized:

spring (

vernal),

summer (

estival),

autumn (

autumnal) and

winter (

hibernal). In

American English,

fall is sometimes used as a synonym for both autumn and autumnal. Ecologists often use a six-season model for temperate

climate regions that includes

pre-spring (

prevernal) and

late summer (

serotinal) as distinct seasons along with the traditional four.

Various calendars used in

South Asia define six seasons.

The six ecological seasons

The four calendar seasons, depicted in an ancient Roman mosaic from

Tunisia.

An Empire style

chariot clock depicting an allegory of the four seasons. France, c. 1822.

Hot regions have two or three seasons; the

rainy (or wet, or

monsoon) season and the

dry season, and, in some

tropical areas, a cool or mild season.

In some parts of the world, special "seasons" are loosely defined based on important events such as a

hurricane season,

tornado season, or a

wildfire season.

Causes and effects

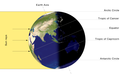

Illumination of the earth at each change of astronomical season

Fig. 1

This diagram shows how the tilt of the Earth's axis aligns with incoming sunlight around the

winter solstice of the Northern Hemisphere. Regardless of the time of day (i.e. the

Earth's rotation on its axis), the

North Pole will be dark, and the

South Pole will be illuminated; see also

arctic winter. In addition to the density of

incident light, the

dissipation of light in the

atmosphere is greater when it falls at a shallow angle.

Axis tilt

The seasons result from the

Earth's

axis of rotation being

tilted with respect to its

orbital plane by an angle of approximately 23.5

degrees.

[3] (This tilt is also known as "obliquity of the

ecliptic".)

Regardless of the time of year, the

northern and

southern hemispheres always experience opposite seasons. This is because during summer or winter, one part of the planet is more directly exposed to the rays of the

Sun (see

Fig. 1) than the other, and this exposure alternates as the Earth revolves in its orbit. For approximately half of the year (from around March 20 to around September 22), the northern hemisphere tips toward the Sun, with the maximum amount occurring on about June 21. For the other half of the year, the same happens, but in the southern hemisphere instead of the northern, with the maximum around December 21. The two instants when the Sun is directly overhead at the Equator are the equinoxes. Also at that moment, both the

North Pole and the

South Pole of the Earth are just on the

terminator, and hence day and night are equally divided between the northern and southern hemispheres. At the March equinox, the northern hemisphere will be experiencing spring as the hours of daylight increase, and the southern hemisphere is experiencing autumn as daylight hours shorten.

The effect of axial tilt is observable as the change in

day length and

altitude of the Sun at

noon (the

culmination of the Sun) during a

year. The low angle of Sun during the winter months means that incoming rays of solar radiation is

spread over a larger area of the Earth's surface, so the light received is more indirect and of lower intensity. Lower intensity light is less able to heat the ground. Between this effect and the shorter daylight hours, the axial tilt of the Earth accounts for most of the seasonal variation in climate in both hemispheres.

-

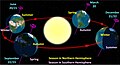

Illumination of Earth by Sun at the northern solstice.

-

Illumination of Earth by Sun at the southern solstice.

-

Diagram of the Earth's seasons as seen from the north. Far right: southern solstice

-

Diagram of the Earth's seasons as seen from the south. Far left: northern solstice

-

Animation of Earth as seen daily from the Sun looking at

UTC+02:00, showing the solstice and changing seasons.

-

Two images showing the amount of reflected sunlight at southern and northern summer solstices respectively (watts / m²).

Elliptical Earth orbit

Compared to axial tilt, other factors contribute little to seasonal temperature changes. The seasons are not the result of the variation in

Earth's distance to the sun because of its elliptical orbit.

[4] In fact, Earth reaches

perihelion (the point in its orbit closest to the

Sun) in January, and it reaches

aphelion (farthest point from the Sun) in July, so the slight contribution of orbital eccentricity opposes the temperature trends of the seasons in the Northern hemisphere.

[5] In general, the effect of orbital eccentricity on Earth's seasons is a 7% variation in sunlight received.

Orbital eccentricity can influence temperatures, but on Earth, this effect is small and is more than counteracted by other factors; research shows that the Earth as a whole is actually slightly warmer when

farther from the sun. This is because the northern hemisphere has more land than the southern, and land warms more readily than sea.

[5] Any noticeable intensification of the southern hemisphere's winters and summers due to Earth's elliptical orbit is mitigated by the abundance of water in the southern hemisphere.

[6]

Maritime and hemispheric

Seasonal weather fluctuations (changes) also depend on factors such as proximity to

oceans or other large bodies of water,

currents in those oceans,

El Niño/ENSO and other oceanic cycles, and prevailing

winds.

In the temperate and polar regions, seasons are marked by changes in the amount of

sunlight, which in turn often causes

cycles of dormancy in plants and

hibernation in animals. These effects vary with latitude and with proximity to bodies of water. For example, the

South Pole is in the middle of the continent of

Antarctica and therefore a considerable distance from the moderating influence of the southern oceans. The

North Pole is in the

Arctic Ocean, and thus its temperature extremes are buffered by the water. The result is that the South Pole is consistently colder during the southern winter than the North Pole during the northern winter.

The cycle of seasons in the polar and temperate zones of one hemisphere is opposite to that in the other. When it is summer in the

Northern Hemisphere, it is winter in the

Southern Hemisphere, and vice versa.

Tropics

In

tropical and

subtropical regions there is little annual fluctuation of sunlight. However, there are seasonal shifts of a rainy global-scale low pressure belt called the

Intertropical convergence zone. As a result, the amount of

precipitation tends to vary more dramatically than the average temperature. When the convergence zone is north of the equator, the tropical areas of the northern hemisphere experience their wet season while the tropics south of the equator have their dry season. This pattern reverses when the convergence zone migrates to a position south of the equator.

A study of temperature records over the past 300 years

[7][page needed] shows that the climatic seasons, and thus the

seasonal year, are governed by the

anomalistic year rather than the

tropical year.

Mid-latitude thermal lag

In meteorological terms, the summer

solstice and winter solstice (or the maximum and minimum

insolation, respectively) do not fall in the middles of summer and winter. The heights of these seasons occur up to seven weeks later because of

seasonal lag. Seasons, though, are not always defined in meteorological terms

In

astronomical reckoning by hours of daylight alone, the solstices and equinoxes are in the

middle of the respective seasons. Because of

seasonal lag due to thermal absorption and release by the oceans, regions with a continental climate which predominate in the Northern hemisphere often consider these four dates to be the

start of the seasons as in the diagram, with the

cross-quarter days considered seasonal midpoints. The length of these seasons is not uniform because of the elliptical orbit of the earth and its

different speeds along that orbit.

[8]

Four-season calendar reckoning

Calendar-based reckoning defines the seasons in relative rather than absolute terms. Accordingly, if floral activity is regularly observed during the coolest quarter of the year in a particular area, it is still considered winter despite the traditional association of flowers with spring and summer. Additionally, the seasons are considered to change on the same dates everywhere that uses a particular calendar method regardless of variations in climate from one area to another. Most calendar-based methods use a four season model to identify the warmest and coolest or coldest seasons which are separated by two intermediate seasons.

Modern mid-latitude meteorological

Animation of seasonal differences especially

snow cover through the year

Meteorological seasons are reckoned by temperature, with summer being the hottest quarter of the year and winter the coldest quarter of the year. In 1780 the Societas Meteorologica Palatina (which became defunct in 1795), an early international organization for meteorology, defined seasons as groupings of three whole months as identified by the Gregorian calendar. Ever since, professional meteorologists all over the world have used this definition.

[9] Therefore, for temperate areas in the Northern hemisphere, spring begins on 1 March, summer on 1 June, autumn on 1 September, and winter on 1 December. For the Southern hemisphere temperate zone, spring begins on 1 September, summer on 1 December, autumn on 1 March, and winter on 1 June.

[10][11]

In Sweden and Finland, meteorologists use a non-calendar based

definition for the seasons based on the temperature. Spring begins when the daily averaged temperature permanently rises above 0 °C, summer begins when the temperature permanently rises above +10 °C, summer ends when the temperature permanently falls below +10 °C and winter begins when the temperature permanently falls below 0 °C. "Permanently" here means that the daily averaged temperature has remained above or below the limit for seven consecutive days. This implies two things: first, the seasons do not begin at fixed dates but must be determined by observation and are known only after the fact; and second, a new season begins at different dates in different parts of the country.

Mid-latitude astronomical

UT date and time of

equinoxes and solstices on Earth[13] |

| event |

equinox |

solstice |

equinox |

solstice |

| month |

March |

June |

September |

December |

| year |

| day |

time |

day |

time |

day |

time |

day |

time |

| 2010 |

20 |

17:32 |

21 |

11:28 |

23 |

03:09 |

21 |

23:38 |

| 2011 |

20 |

23:21 |

21 |

17:16 |

23 |

09:04 |

22 |

05:30 |

| 2012 |

20 |

05:14 |

20 |

23:09 |

22 |

14:49 |

21 |

11:12 |

| 2013 |

20 |

11:02 |

21 |

05:04 |

22 |

20:44 |

21 |

17:11 |

| 2014 |

20 |

16:57 |

21 |

10:51 |

23 |

02:29 |

21 |

23:03 |

| 2015 |

20 |

22:45 |

21 |

16:38 |

23 |

08:20 |

22 |

04:48 |

| 2016 |

20 |

04:30 |

20 |

22:34 |

22 |

14:21 |

21 |

10:44 |

| 2017 |

20 |

10:28 |

21 |

04:24 |

22 |

20:02 |

21 |

16:28 |

| 2018 |

20 |

16:15 |

21 |

10:07 |

23 |

01:54 |

21 |

22:23 |

| 2019 |

20 |

21:58 |

21 |

15:54 |

23 |

07:50 |

22 |

04:19 |

| 2020 |

20 |

03:50 |

20 |

21:44 |

22 |

13:31 |

21 |

10:02 |

Astronomical timing as the basis for designating the temperate seasons dates back at least to the Julian calendar used by the ancient Romans. It continues to be used on many modern Gregorian calendars world-wide, although some countries like Australia, New Zealand, and Russia prefer to use meteorological reckoning. The precise timing of the seasons is determined by the exact times of transit of the sun over the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn for the

solstices and the times of the sun's transit over the equator for the

equinoxes, or a traditional date close to these times.

[14]

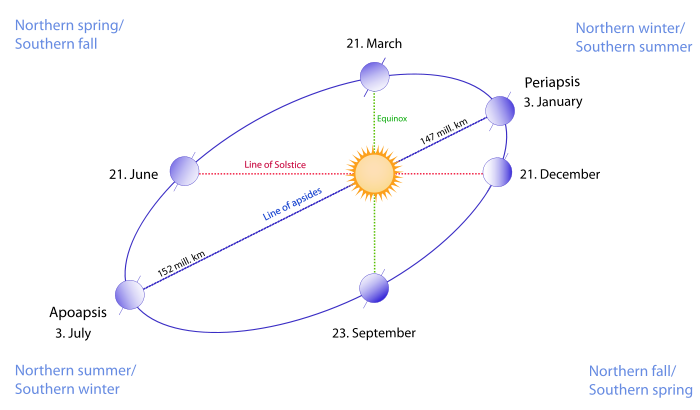

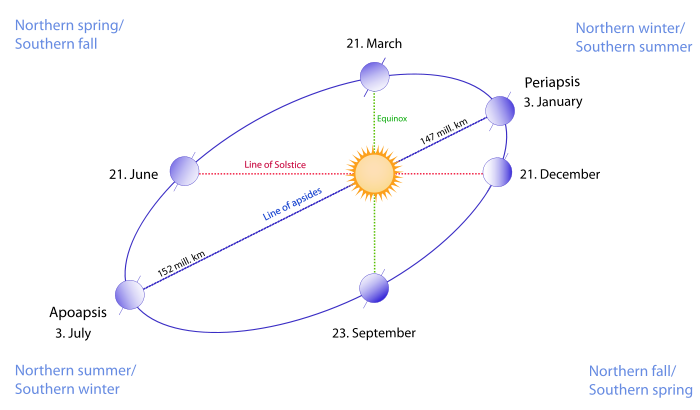

The following diagram shows the relation between the line of solstice and the line of

apsides of Earth's elliptical orbit. The orbital ellipse (with eccentricity exaggerated for effect) goes through each of the six Earth images, which are sequentially the

perihelion (periapsis—nearest point to the sun) on anywhere from 2 January to 5 January, the point of March

equinox on 19, 20 or 21 March, the point of June

solstice on 20 or 21 June, the

aphelion (apoapsis—farthest point from the sun) on anywhere from 4 July to 7 July, the September equinox on 22 or 23 September, and the December solstice on 21 or 22 December.

Note: Distances are exaggerated and not to scale

The astronomical seasons are not of equal length, because of the

elliptical nature of the orbit of the Earth, as discovered by

Johannes Kepler. From the March equinox it takes 92.75 days until the June solstice, then 93.65 days until the September equinox, 89.85 days until the December solstice and finally 88.99 days until the March equinox.

Variation due to calendar misalignment

The time of the equinoxes and solstices are not fixed with respect to the modern Gregorian calendar, but fall about six hours later every year, amounting to one full day in four years. They are reset by the occurrence of a leap year.

The Gregorian calendar is designed to keep the March equinox on 21 March as accurately as is practical, though it does not always achieve this.

Also see: Gregorian calendar seasonal error.

Currently, the most common equinox and solstice dates are March 20, June 21, September 22 or 23 and December 21; the four-year average will slowly shift to earlier times in coming years. This shift is a full day in about 70 years (compensated mainly by the century "leap year" rules of the Gregorian calendar). This also means that in many years of the twentieth century, the dates of March 21, June 22, September 23 and December 22 were much more common, so older books teach (and older people may still remember) these dates.

Note that all the times are given in

UTC (roughly speaking, the time at

Greenwich, ignoring British Summer Time). People living farther to the east (Asia and Australia), whose local times are in advance, will see the astronomical seasons apparently start later; for example, in

Tonga (UTC+13), an equinox occurred on September 24, 1999, a date which will not crop up again until 2103. On the other hand, people living far to the west (America) whose clocks run behind UTC may experience an equinox as early as March 19.

Change over time

Over thousands of years, the Earth's

axial tilt and orbital eccentricity vary (see

Milankovitch cycles). Thus, ten thousand years from now Earth's northern winter will occur at aphelion and northern summer at

perihelion. The severity of seasonal change—the average temperature difference between summer and winter in location—will also change over time because the Earth's axial tilt fluctuates between 22.1 and 24.5 degrees.

Smaller irregularities in the times are caused by perturbations of the Moon and the other planets.

Traditional solar: Europe and East Asia

Solar timing is based on

insolation in which the solstices and equinoxes are seen as the midpoints of the seasons. It was the method for reckoning seasons in medieval Europe, especially by the

Celts, and is still ceremonially observed in some east Asian countries. Summer is defined as the quarter of the year with the greatest insolation and winter as the quarter with the least.

The solar seasons change at the

cross-quarter days, which are about 3–4 weeks earlier than the meteorological seasons and 6–7 weeks earlier than seasons starting at equinoxes and solstices. Thus, the day of greatest insolation is designated "midsummer" as noted in

William Shakespeare's play

A Midsummer Night's Dream, which is set on the summer solstice. On the Celtic calendar, the traditional first day of winter is 1 November (

Samhain, the Celtic origin of

Halloween); spring starts 1 February (

Imbolc, the Celtic origin of

Groundhog Day); summer begins 1 May (

Beltane, the Celtic origin of

May Day); the first day of autumn is 1 August (Celtic

Lughnasadh). The Celtic dates corresponded to four

Pagan agricultural festivals.

The

traditional calendar in China forms the basis of other such systems in

East Asia. Its seasons are traditionally based on 24 periods known as

solar terms.

[15] The four seasons

chūn (

春),

xià (

夏),

qiū (

秋), and

dōng (

冬) are universally translated as "spring", "summer", "autumn", and "winter" but actually begin much earlier, with the solstices and equinoxes forming the

midday of each season rather than their

start. Astronomically, the seasons are said to begin on Lichun (

立春,

lit. "standing spring") on 7 February, Lixia (

立夏) on 10 May, Liqiu (

立秋) on 10 August, and Lidong (

立冬) on 10 November. These dates were not part of the traditional lunar calendar, however, and moveable holidays such as

Chinese New Year and the

Mid-Autumn Festival are more closely associated with the seasons.

South Asian (mid-latitude and tropical) six-season calendars

Some calendars in south Asia use a six-season method where the number of seasons between summer and winter can number from one to three. The dates are fixed at even intervals of months.

In the

Hindu calendar of tropical and subtropical India, there are six seasons or

Ritu that are calendar-based in the sense of having fixed dates:

Vasanta (spring), Greeshma (summer),

Varsha (

monsoon),

Sharad (autumn), Hemanta (early winter), and Shishira (prevernal or late winter). The six seasons are ascribed to two months each of the twelve months in the Hindu calendar. The rough correspondences are:

Bengali Calendar is similar but differs in start and end time. It has the following seasons or ritu:

The

Tamil calendar follows a similar pattern of six Seasons

| Tamil season |

Gregorian Months |

Tamil Months |

| IlaVenil (Spring) |

April 15 to June 14 |

Chithirai and Vaikasi |

| MuthuVenil (Summer) |

June 15 to August 14 |

Aani and Aadi |

| Kaar (Monsoon) |

August 15 to October 14 |

Avani and Purattasi |

| Kulir (Autumn) |

October 15 to December 14 |

Aipasi and Karthikai |

| MunPani (Winter) |

December 15 to February 14 |

Margazhi and Thai |

| PinPani (Prevernal) |

February 15 to April 15 |

Maasi and Panguni |

Polar day and night

Any point north of the

Arctic Circle or south of the

Antarctic Circle will have one period in the summer when the sun does not set, and one period in the winter when the sun does not rise. At progressively higher latitudes, the maximum periods of "

midnight sun" and "

polar night" are progressively longer.

For example, at the military and weather station

Alert located at 82°30′05″N and 62°20′20″W, on the northern tip of

Ellesmere Island,

Canada (about 450

nautical miles or 830 km from the

North Pole), the sun begins to peek above the horizon for minutes per day at the end of February and each day it climbs higher and stays up longer; by 21 March, the sun is up for over 12 hours. On 6 April the sun rises at 0522

UTC and remains above the horizon until it sets below the horizon again on 6 September at 0335 UTC. By October 13 the sun is above the horizon for only 1 hour 30 minutes and on October 14 it does not rise above the horizon at all and remains below the horizon until it rises again on 27 February.

[16]

First light comes in late January because the sky has

twilight, being a glow on the horizon, for increasing hours each day, for more than a month before the sun first appears with its disc above the horizon. From mid-November to mid-January, there is no twilight.

In the weeks surrounding 21 June, in the northern polar region, the sun is at its highest elevation, appearing to circle the sky there without going below the horizon. Eventually, it does go below the horizon, for progressively longer periods each day until around the middle of October, when it disappears for the last time until the following February. For a few more weeks, "day" is marked by decreasing periods of twilight. Eventually, from mid-November to mid-January, there is no twilight and it is continuously dark. In mid January the first faint wash of twilight briefly touches the horizon (for just minutes per day), and then twilight increases in duration with increasing brightness each day until sunrise at end of February, then on 6 April the sun remains above the horizon until mid October.

Non-calendar-based reckoning

Seasonal changes regarding a tree over a year

Ecologically speaking, a season is a period of the year in which only certain types of floral and animal events happen (e.g.: flowers bloom—spring;

hedgehogs hibernate—winter). So, if we can observe a change in daily floral/animal events, the season is changing. In this sense, ecological seasons are defined in absolute terms, unlike calendar-based methods in which the seasons are relative. If specific conditions associated with a particular ecological season don't normally occur in a particular region, then that area cannot be said to experience that season on a regular basis.

Modern mid-latitude ecological

Six seasons can be distinguished which do not have fixed calendar-based dates like the meteorological and astronomical seasons.

[17] Mild

temperate regions tend to experience the beginning of the hibernal season up to a month later than cool temperate areas, while the prevernal and vernal seasons begin up to a month earlier. For example, prevernal

crocus blooms typically appear as early as February in mild coastal areas of

British Columbia, the

British Isles, and western and southern

Europe. The actual dates for each season vary by climate region and can shift from one year to the next. Average dates listed here are for mild and cool temperate climate zones in the Northern Hemisphere:

- Prevernal (early or pre-spring): Begins February or late January (mild temperate), March (cool temperate). Deciduous tree buds begin to swell. Migrating birds fly from winter to summer habitats.

- Vernal (spring): Begins March (mild temperate), April (cool temperate). Tree buds burst into leaves. Birds establish territories and begin mating and nesting.

- Estival (high summer): Begins June in most temperate climates. Trees in full leaf. Birds hatch and raise offspring.

- Serotinal (late summer): Generally begins mid to late August. Deciduous leaves begin to change color. Young birds reach maturity and join other adult birds preparing for autumn migration.

- Autumnal (autumn): Generally begins mid to late September. Tree leaves in full color then turn brown and fall to the ground. Birds migrate back to wintering areas.

- Hibernal (winter): Begins December (mild temperate), November (cool temperate). Deciduous trees are bare and fallen leaves begin to decay. Migrating birds settled in winter habitats.

Modern tropical ecological

In the tropics, where seasonal dates also vary, it is more common to speak of the

rainy (or wet, or

monsoon) season versus the

dry season. For example, in

Nicaragua the dry season (November to April) is called 'summer' and the rainy season (May to October) is called 'winter', even though it is located in the northern hemisphere. In some tropical areas a three-way division into hot, rainy, and cool season is used. There is no noticeable change in the amount of sunlight at different times of the year. However, many regions (such as the northern

Indian ocean) are subject to

monsoon rain and wind cycles.

Floral and animal activity variation near the equator depends more on wet/dry cycles than seasonal temperature variations, with different species flowering (or emerging from cocoons) at specific times before, during, or after the monsoon season. Thus, the tropics are characterized by numerous "mini-seasons" within the larger seasonal blocks of time.

Indigenous ecological (polar, mid-latitude, and tropical)

Indigenous people in polar, temperate and tropical climates of northern Eurasia, the Americas, Africa, Oceania, and Australia have traditionally defined the seasons ecologically by observing the activity of the plants, animals and weather around them. Each separate tribal group traditionally observes different seasons determined according to local criteria that can vary from the hibernation of polar bears on the arctic tundras to the growing seasons of plants in the tropical rainforests. In Australia, some tribes have up to eight seasons in a year,

[10] as do the Sami people in Scandinavia. Many indigenous people who no longer live directly off the land in traditional often nomadic styles, now observe modern methods of seasonal reckoning according to what is customary in their particular country or region.

"Official" designations

As noted, a variety of dates are used in different countries to mark the changes of seasons, especially those that are calendar based. These different observances are often declared "official" within their respective jurisdictions, especially by the media and promotional organizations in each nation.

[18][19] However they are mainly a matter of custom only, and have not generally been proclaimed by governments north or south of the equator for civil purposes.

[20]