From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

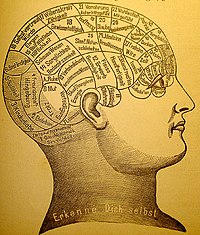

A phrenological mapping[1] of the brain. Phrenology was among the first attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain.

René Descartes' illustration of mind/body dualism. Descartes believed inputs are passed on by the sensory organs to the epiphysis in the brain and from there to the immaterial spirit.[2]

A mind /ˈmaɪnd/ is the set of cognitive faculties that enables consciousness, perception, thinking, judgement, and memory—a characteristic of humans, but which also may apply to other life forms.[3][4]

A lengthy tradition of inquiries in philosophy, religion, psychology and cognitive science has sought to develop an understanding of what a mind is and what its distinguishing properties are. The main question regarding the nature of mind is its relation to the physical brain and nervous system – a question which is often framed as the Mind-body problem, which considers whether mind is somehow separate from physical existence (dualism and idealism[5]), deriving from and/or reducible to physical phenomena such as neuronal activity (physicalism), or whether the mind is identical with the brain or some activity of the brain.[6] Another question concerns which types of beings are capable of having minds, for example whether mind is exclusive to humans, possessed also by some or all animals, by all living things, or whether mind can also be a property of some types of man-made machines.

Whatever its relation to the physical body it is generally agreed that mind is that which enables a being to have subjective awareness and intentionality towards their environment, to perceive and respond to stimuli with some kind of agency, and to have consciousness, including thinking and feeling.[3][7]

Important philosophers of mind include Mulla Sadra, Plato, Descartes, Leibniz, Kant, Martin Heidegger, John Searle, Daniel Dennett and many others. The description and definition is also a part of psychology where psychologists such as Sigmund Freud and William James have developed influential theories about the nature of the human mind. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries the field of cognitive science emerged and developed many varied approaches to the description of mind and its related phenomena. The possibility of non-human minds is also explored in the field of artificial intelligence, which works closely in relation with cybernetics and information theory to understand the ways in which human mental phenomena can be replicated by nonbiological machines.

The concept of mind is understood in many different ways by many different cultural and religious traditions. Some see mind as a property exclusive to humans whereas others ascribe properties of mind to non-living entities (e.g. panpsychism and animism), to animals and to deities. Some of the earliest recorded speculations linked mind (sometimes described as identical with soul or spirit) to theories concerning both life after death, and cosmological and natural order, for example in the doctrines of Zoroaster, the Buddha, Plato, Aristotle, and other ancient Greek, Indian and, later, Islamic and medieval European philosophers.

Etymology

The original meaning of Old English gemynd was the faculty of memory, not of thought in general. Hence call to mind, come to mind, keep in mind, to have mind of, etc. The word retains this sense in Scotland. Old English had other words to express "mind", such as hyge "mind, spirit".The meaning of "memory" is shared with Old Norse, which has munr. The word is originally from a PIE verbal root *men-, meaning "to think, remember", whence also Latin mens "mind", Sanskrit manas "mind" and Greek μένος "mind, courage, anger".

The generalization of mind to include all mental faculties, thought, volition, feeling and memory, gradually develops over the 14th and 15th centuries.[8]

Definitions

The attributes that make up the mind is debated. Some psychologists argue that only the "higher" intellectual functions constitute mind, particularly reason and memory. In this view the emotions — love, hate, fear, joy — are more primitive or subjective in nature and should be seen as different from the mind as such. Others argue that various rational and emotional states cannot be so separated, that they are of the same nature and origin, and should therefore be considered all part of what we call the mind.In popular usage, mind is frequently synonymous with thought: the private conversation with ourselves that we carry on "inside our heads." Thus we "make up our minds," "change our minds" or are "of two minds" about something. One of the key attributes of the mind in this sense is that it is a private sphere to which no one but the owner has access. No one else can "know our mind." They can only interpret what we consciously or unconsciously communicate.

Mental faculties

Broadly speaking, mental faculties are the various functions of the mind, or things the mind can "do".Thought is a mental act that allows humans to make sense of things in the world, and to represent and interpret them in ways that are significant, or which accord with their needs, attachments, goals, commitments, plans, ends, desires, etc. Thinking involves the symbolic or semiotic mediation of ideas or data, as when we form concepts, engage in problem solving, reasoning and making decisions. Words that refer to similar concepts and processes include deliberation, cognition, ideation, discourse and imagination.

Thinking is sometimes described as a "higher" cognitive function and the analysis of thinking processes is a part of cognitive psychology. It is also deeply connected with our capacity to make and use tools; to understand cause and effect; to recognize patterns of significance; to comprehend and disclose unique contexts of experience or activity; and to respond to the world in a meaningful way.

Memory is the ability to preserve, retain, and subsequently recall, knowledge, information or experience. Although memory has traditionally been a persistent theme in philosophy, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries also saw the study of memory emerge as a subject of inquiry within the paradigms of cognitive psychology. In recent decades, it has become one of the pillars of a new branch of science called cognitive neuroscience, a marriage between cognitive psychology and neuroscience.

Imagination is the activity of generating or evoking novel situations, images, ideas or other qualia in the mind. It is a characteristically subjective activity, rather than a direct or passive experience. The term is technically used in psychology for the process of reviving in the mind percepts of objects formerly given in sense perception. Since this use of the term conflicts with that of ordinary language, some psychologists have preferred to describe this process as "imaging" or "imagery" or to speak of it as "reproductive" as opposed to "productive" or "constructive" imagination. Things imagined are said to be seen in the "mind's eye". Among the many practical functions of imagination are the ability to project possible futures (or histories), to "see" things from another's perspective, and to change the way something is perceived, including to make decisions to respond to, or enact, what is imagined.

Consciousness in mammals (this includes humans) is an aspect of the mind generally thought to comprise qualities such as subjectivity, sentience, and the ability to perceive the relationship between oneself and one's environment. It is a subject of much research in philosophy of mind, psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive science. Some philosophers divide consciousness into phenomenal consciousness, which is subjective experience itself, and access consciousness, which refers to the global availability of information to processing systems in the brain.[9] Phenomenal consciousness has many different experienced qualities, often referred to as qualia. Phenomenal consciousness is usually consciousness of something or about something, a property known as intentionality in philosophy of mind.

Mental content

Mental contents are those items that are thought of as being "in" the mind, and capable of being formed and manipulated by mental processes and faculties. Examples include thoughts, concepts, memories, emotions, percepts and intentions. Philosophical theories of mental content include internalism, externalism, representationalism and intentionality.Memetics

Memetics is a theory of mental content based on an analogy with Darwinian evolution, which was originated by Richard Dawkins and Douglas Hofstadter in the 1980s. It is an evolutionary model of cultural information transfer. A meme, analogous to a gene, is an idea, belief, pattern of behaviour (etc.) "hosted" in one or more individual minds, and can reproduce itself from mind to mind. Thus what would otherwise be regarded as one individual influencing another to adopt a belief, is seen memetically as a meme reproducing itself.Relation to the brain

In animals, the brain, or encephalon (Greek for "in the head"), is the control center of the central nervous system, responsible for thought. In most animals, the brain is located in the head, protected by the skull and close to the primary sensory apparatus of vision, hearing, equilibrioception, taste and olfaction. While all vertebrates have a brain, most invertebrates have either a centralized brain or collections of individual ganglia. Primitive animals such as sponges do not have a brain at all. Brains can be extremely complex. For example, the human brain contains around 86 billion neurons, each linked to as many as 10,000 others.[10][11]Understanding the relationship between the brain and the mind – mind-body problem is one of the central issues in the history of philosophy – is a challenging problem both philosophically and scientifically.[12] There are three major philosophical schools of thought concerning the answer: dualism, materialism, and idealism. Dualism holds that the mind exists independently of the brain;[13] materialism holds that mental phenomena are identical to neuronal phenomena;[14] and idealism holds that only mental phenomena exist.[14]

Through most of history many philosophers found it inconceivable that cognition could be implemented by a physical substance such as brain tissue (that is neurons and synapses).[15] Descartes, who thought extensively about mind-brain relationships, found it possible to explain reflexes and other simple behaviors in mechanistic terms, although he did not believe that complex thought, and language in particular, could be explained by reference to the physical brain alone.[16]

The most straightforward scientific evidence of a strong relationship between the physical brain matter and the mind is the impact physical alterations to the brain have on the mind, such as with traumatic brain injury and psychoactive drug use.[17] Philosopher Patricia Churchland notes that this drug-mind interaction indicates an intimate connection between the brain and the mind.[18]

In addition to the philosophical questions, the relationship between mind and brain involves a number of scientific questions, including understanding the relationship between mental activity and brain activity, the exact mechanisms by which drugs influence cognition, and the neural correlates of consciousness.

Evolutionary history of the human mind

The evolution of human intelligence refers to a set of theories that attempt to explain how human intelligence has evolved. The question is closely tied to the evolution of the human brain, and to the emergence of human language.The timeline of human evolution spans some 7 million years, from the separation of the Pan genus until the emergence of behavioral modernity by 50,000 years ago. Of this timeline, the first 3 million years concern Sahelanthropus, the following 2 million concern Australopithecus, while the final 2 million span the history of actual human species (the Paleolithic).

Many traits of human intelligence, such as empathy, theory of mind, mourning, ritual, and the use of symbols and tools, are already apparent in great apes although in lesser sophistication than in humans.

There is a debate between supporters of the idea of a sudden emergence of intelligence, or "Great leap forward" and those of a gradual or continuum hypothesis.

Theories of the evolution of intelligence include:

- Robin Dunbar's social brain hypothesis[19]

- Geoffrey Miller's sexual selection hypothesis[20]

- The ecological dominance-social competition (EDSC)[21] explained by Mark V. Flinn, David C. Geary and Carol V. Ward based mainly on work by Richard D. Alexander.

- The idea of intelligence as a signal of good health and resistance to disease.

- The Group selection theory contends that organism characteristics that provide benefits to a group (clan, tribe, or larger population) can evolve despite individual disadvantages such as those cited above.

- The idea that intelligence is connected with nutrition, and thereby with status[22] A higher IQ could be a signal that an individual comes from and lives in a physical and social environment where nutrition levels are high, and vice versa.

Philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is the branch of philosophy that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness and their relationship to the physical body. The mind-body problem, i.e. the relationship of the mind to the body, is commonly seen as the central issue in philosophy of mind, although there are other issues concerning the nature of the mind that do not involve its relation to the physical body.[23] José Manuel Rodriguez Delgado writes, "In present popular usage, soul and mind are not clearly differentiated and some people, more or less consciously, still feel that the soul, and perhaps the mind, may enter or leave the body as independent entities."[24]Dualism and monism are the two major schools of thought that attempt to resolve the mind-body problem. Dualism is the position that mind and body are in some way separate from each other. It can be traced back to Plato,[25] Aristotle[26][27][28] and the Samkhya and Yoga schools of Hindu philosophy,[29] but it was most precisely formulated by René Descartes in the 17th century.[30] Substance dualists argue that the mind is an independently existing substance, whereas Property dualists maintain that the mind is a group of independent properties that emerge from and cannot be reduced to the brain, but that it is not a distinct substance.[31]

The 20th century philosopher Martin Heidegger suggested that subjective experience and activity (i.e. the "mind") cannot be made sense of in terms of Cartesian "substances" that bear "properties" at all (whether the mind itself is thought of as a distinct, separate kind of substance or not). This is because the nature of subjective, qualitative experience is incoherent in terms of – or semantically incommensurable with the concept of – substances that bear properties. This is a fundamentally ontological argument.[32]

The philosopher of cognitive science Daniel Dennett, for example, argues there is no such thing as a narrative center called the "mind", but that instead there is simply a collection of sensory inputs and outputs: different kinds of "software" running in parallel.[33] Psychologist B.F. Skinner argued that the mind is an explanatory fiction that diverts attention from environmental causes of behavior;[34] he considered the mind a "black box" and thought that mental processes may be better conceived of as forms of covert verbal behavior.[35][36]

Mind/body perspectives

Monism is the position that mind and body are not physiologically and ontologically distinct kinds of entities. This view was first advocated in Western Philosophy by Parmenides in the 5th Century BC and was later espoused by the 17th Century rationalist Baruch Spinoza.[37] According to Spinoza's dual-aspect theory, mind and body are two aspects of an underlying reality which he variously described as "Nature" or "God".- Physicalists argue that only the entities postulated by physical theory exist, and that the mind will eventually be explained in terms of these entities as physical theory continues to evolve.

- Idealists maintain that the mind is all that exists and that the external world is either mental itself, or an illusion created by the mind.

- Neutral monists adhere to the position that perceived things in the world can be regarded as either physical or mental depending on whether one is interested in their relationship to other things in the world or their relationship to the perceiver. For example, a red spot on a wall is physical in its dependence on the wall and the pigment of which it is made, but it is mental in so far as its perceived redness depends on the workings of the visual system. Unlike dual-aspect theory, neutral monism does not posit a more fundamental substance of which mind and body are aspects.

Many modern philosophers of mind adopt either a reductive or non-reductive physicalist position, maintaining in their different ways that the mind is not something separate from the body.[38] These approaches have been particularly influential in the sciences, e.g. in the fields of sociobiology, computer science, evolutionary psychology and the various neurosciences.[39][40][41][42] Other philosophers, however, adopt a non-physicalist position which challenges the notion that the mind is a purely physical construct.

- Reductive physicalists assert that all mental states and properties will eventually be explained by scientific accounts of physiological processes and states.[43][44][45]

- Non-reductive physicalists argue that although the brain is all there is to the mind, the predicates and vocabulary used in mental descriptions and explanations are indispensable, and cannot be reduced to the language and lower-level explanations of physical science.[46][47]

Scientific study

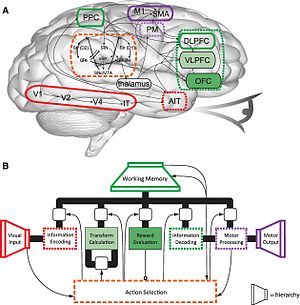

Simplified diagram of Spaun, a 2.5-million-neuron computational model of the brain. (A) The corresponding physical regions and connections of the human brain. (B) The mental architecture of Spaun.[52]

Neuroscience

Neuroscience studies the nervous system, the physical basis of the mind. At the systems level, neuroscientists investigate how biological neural networks form and physiologically interact to produce mental functions and content such as reflexes, multisensory integration, motor coordination, circadian rhythms, emotional responses, learning, and memory. At a larger scale, efforts in computational neuroscience have developed large-scale models that simulate simple, functioning brains.[52] As of 2012, such models include the thalamus, basal ganglia, prefrontal cortex, motor cortex, and occipital cortex, and consequentially simulated brains can learn, respond to visual stimuli, coordinate motor responses, form short-term memories, and learn to respond to patterns. Currently, researchers aim to program the hippocampus and limbic system, hypothetically imbuing the simulated mind with long-term memory and crude emotions.[53]By contrast, affective neuroscience studies the neural mechanisms of personality, emotion, and mood primarily through experimental tasks.

Cognitive Science

Cognitive science examines the mental functions that give rise to information processing, termed cognition. These include attention, memory, producing and understanding language, learning, reasoning, problem solving, and decision making. Cognitive science seeks to understand thinking "in terms of representational structures in the mind and computational procedures that operate on those structures".[54]

Psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of human behavior, mental functioning, and experience. As both an academic and applied discipline, Psychology involves the scientific study of mental processes such as perception, cognition, emotion, personality, as well as environmental influences, such as social and cultural influences, and interpersonal relationships, in order to devise theories of human behavior. Psychology also refers to the application of such knowledge to various spheres of human activity, including problems of individuals' daily lives and the treatment of mental health problems.Psychology differs from the other social sciences (e.g., anthropology, economics, political science, and sociology) due to its focus on experimentation at the scale of the individual, or individuals in small groups as opposed to large groups, institutions or societies. Historically, psychology differed from biology and neuroscience in that it was primarily concerned with mind rather than brain. Modern psychological science incorporates physiological and neurological processes into its conceptions of perception, cognition, behaviour, and mental disorders.

Mental health

By analogy with the health of the body, one can speak metaphorically of a state of health of the mind, or mental health. Merriam-Webster defines mental health as "A state of emotional and psychological well-being in which an individual is able to use his or her cognitive and emotional capabilities, function in society, and meet the ordinary demands of everyday life." According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there is no one "official" definition of mental health. Cultural differences, subjective assessments, and competing professional theories all affect how "mental health" is defined. In general, most experts agree that "mental health" and "mental illness" are not opposites. In other words, the absence of a recognized mental disorder is not necessarily an indicator of mental health.One way to think about mental health is by looking at how effectively and successfully a person functions. Feeling capable and competent; being able to handle normal levels of stress, maintaining satisfying relationships, and leading an independent life; and being able to "bounce back," or recover from difficult situations, are all signs of mental health.

Psychotherapy is an interpersonal, relational intervention used by trained psychotherapists to aid clients in problems of living. This usually includes increasing individual sense of well-being and reducing subjective discomforting experience. Psychotherapists employ a range of techniques based on experiential relationship building, dialogue, communication and behavior change and that are designed to improve the mental health of a client or patient, or to improve group relationships (such as in a family). Most forms of psychotherapy use only spoken conversation, though some also use various other forms of communication such as the written word, art, drama, narrative story, or therapeutic touch. Psychotherapy occurs within a structured encounter between a trained therapist and client(s). Purposeful, theoretically based psychotherapy began in the 19th century with psychoanalysis; since then, scores of other approaches have been developed and continue to be created.

Non-human minds

Animal intelligence

Animal cognition, or cognitive ethology, is the title given to a modern approach to the mental capacities of animals. It has developed out of comparative psychology, but has also been strongly influenced by the approach of ethology, behavioral ecology, and evolutionary psychology. Much of what used to be considered under the title of "animal intelligence" is now thought of under this heading. Animal language acquisition, attempting to discern or understand the degree to which animal cognition can be revealed by linguistics-related study, has been controversial among cognitive linguists.Artificial intelligence

In 1950 Alan M. Turing published "Computing machinery and intelligence" in Mind, in which he proposed that machines could be tested for intelligence using questions and answers. This process is now named the Turing Test. The term Artificial Intelligence (AI) was first used by John McCarthy who considered it to mean "the science and engineering of making intelligent machines".[56] It can also refer to intelligence as exhibited by an artificial (man-made, non-natural, manufactured) entity. AI is studied in overlapping fields of computer science, psychology, neuroscience and engineering, dealing with intelligent behavior, learning and adaptation and usually developed using customized machines or computers.

Research in AI is concerned with producing machines to automate tasks requiring intelligent behavior. Examples include control, planning and scheduling, the ability to answer diagnostic and consumer questions, handwriting, natural language, speech and facial recognition. As such, the study of AI has also become an engineering discipline, focused on providing solutions to real life problems, knowledge mining, software applications, strategy games like computer chess and other video games. One of the biggest limitations of AI is in the domain of actual machine comprehension. Consequentially natural language understanding and connectionism (where behavior of neural networks is investigated) are areas of active research and development.

The debate about the nature of the mind is relevant to the development of artificial intelligence. If the mind is indeed a thing separate from or higher than the functioning of the brain, then hypothetically it would be much more difficult to recreate within a machine, if it were possible at all. If, on the other hand, the mind is no more than the aggregated functions of the brain, then it will be possible to create a machine with a recognisable mind (though possibly only with computers much different from today's), by simple virtue of the fact that such a machine already exists in the form of the human brain.

In religion

Many religions associate spiritual qualities to the human mind. These are often tightly connected to their mythology and afterlife.The Indian philosopher-sage Sri Aurobindo attempted to unite the Eastern and Western psychological traditions with his integral psychology, as have many philosophers and New religious movements. Judaism teaches that "moach shalit al halev", the mind rules the heart. Humans can approach the Divine intellectually, through learning and behaving according to the Divine Will as enclothed in the Torah, and use that deep logical understanding to elicit and guide emotional arousal during prayer. Christianity has tended to see the mind as distinct from the soul (Greek nous) and sometimes further distinguished from the spirit. Western esoteric traditions sometimes refer to a mental body that exists on a plane other than the physical. Hinduism's various philosophical schools have debated whether the human soul (Sanskrit atman) is distinct from, or identical to, Brahman, the divine reality. Taoism sees the human being as contiguous with natural forces, and the mind as not separate from the body. Confucianism sees the mind, like the body, as inherently perfectible.

Buddhism

According to Buddhist philosopher Dharmakirti, the mind has two fundamental qualities: "clarity and cognizes". If something is not those two qualities, it cannot validly be called mind. "Clarity" refers to the fact that mind has no color, shape, size, location, weight, or any other physical characteristic, and "cognizes" that it functions to know or perceive objects.[57] "Knowing" refers to the fact that mind is aware of the contents of experience, and that, in order to exist, mind must be cognizing an object. You cannot have a mind - whose function is to cognize an object - existing without cognizing an object.Mind, in Buddhism, is also described as being "space-like" and "illusion-like". Mind is space-like in the sense that it is not physically obstructive. It has no qualities which would prevent it from existing. In Mahayana Buddhism, mind is illusion-like in the sense that it is empty of inherent existence. This does not mean it does not exist, it means that it exists in a manner that is counter to our ordinary way of misperceiving how phenomena exist, according to Buddhism. When the mind is itself cognized properly, without misperceiving its mode of existence, it appears to exist like an illusion. There is a big difference however between being "space and illusion" and being "space-like" and "illusion-like". Mind is not composed of space, it just shares some descriptive similarities to space. Mind is not an illusion, it just shares some descriptive qualities with illusions.

Buddhism posits that there is no inherent, unchanging identity (Inherent I, Inherent Me) or phenomena (Ultimate self, inherent self, Atman, Soul, Self-essence, Jiva, Ishvara, humanness essence, etc.) which is the experiencer of our experiences and the agent of our actions. In other words, human beings consist of merely a body and a mind, and nothing extra. Within the body there is no part or set of parts which is - by itself or themselves - the person. Similarly, within the mind there is no part or set of parts which are themselves "the person". A human being merely consists of five aggregates, or skandhas and nothing else.

In the same way, "mind" is what can be validly conceptually labelled onto our mere experience of clarity and knowing. There is something separate and apart from clarity and knowing which is "Awareness", in Buddhism. "Mind" is that part of experience the sixth sens door, which can be validly referred to as mind by the concept-term "mind". There is also not "objects out there, mind in here, and experience somewhere in-between". There is a third thing called "awareness" which exists being aware of the contents of mind and what mind cognizes. There are five senses (arising of mere experience: shapes, colors, the components of smell, components of taste, components of sound, components of touch) and mind as the sixth institution; this means, expressly, that there can be a third thing called "awareness" and a third thing called "experiencer who is aware of the experience". This awareness is deeply related to "no-self" because it does not judge the experience with craving or aversion.

Clearly, the experience arises and is known by mind, but there is a third thing calls Sathi what is the "real experiencer of the experience" that sits apart from the experience and which can be aware of the experience in 4 levels. (Maha Sathipatthana Sutta.)

- Body

- Sensations (Changes of the body mind.)

- Mind,

- Contents of the mind. (Changes of the body mind.)

Mortality of the mind

Due to the mind-body problem, a lot of interest and debate surrounds the question of what happens to one's conscious mind as one's body dies. During brain death all brain function permanently ceases, according to the current neuroscientific view which sees these processes as the physical basis of mental phenomena, the mind fails to survive brain death and ceases to exist. This permanent loss of consciousness after death is often called "eternal oblivion". The belief that some spiritual or incorporeal component (soul) exists and that it is preserved after death is described by the term "afterlife".In pseudoscience

Parapsychology

Parapsychology is the scientific study of certain types of paranormal phenomena, or of phenomena which appear to be paranormal,[58] for instance precognition, telekinesis and telepathy.The term is based on the Greek para (beside/beyond), psyche (soul/mind), and logos (account/explanation) and was coined by psychologist Max Dessoir in or before 1889.[59] J. B. Rhine later popularized "parapsychology" as a replacement for the earlier term "psychical research", during a shift in methodologies which brought experimental methods to the study of psychic phenomena.[59] Parapsychology is controversial, with many scientists believing that psychic abilities have not been demonstrated to exist.[60][61][62][63][64] The status of parapsychology as a science has also been disputed,[65] with many scientists regarding the discipline as pseudoscience.[66][67][68]