From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

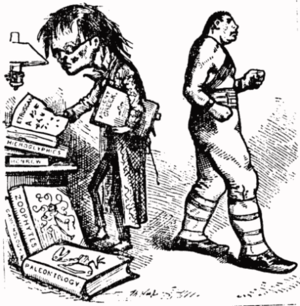

Intellectual and anti-intellectual: Political cartoonist Thomas Nast contrasts the reedy scholar with the bovine boxer, epitomizing the populist view of reading and study as antithetical to sport and athleticism. Note the disproportionate heads/bodies, with the size of the head representing "mental" ability and intelligence, and the size of the body representing kinesthetic talent and "physical" ability.

Anti-intellectualism is hostility towards and mistrust of intellect, intellectuals, and intellectual pursuits, usually expressed as the derision of education, philosophy, literature, art, and science, as impractical and contemptible. Alternatively, self-described intellectuals who are alleged to fail to adhere to rigorous standards of scholarship may be described as anti-intellectuals although pseudo-intellectualism is a more commonly, and perhaps more accurately, used description for this phenomenon.

In public discourse, anti-intellectuals are usually perceived and publicly present themselves as champions of the common folk—populists against political elitism and academic elitism—proposing that the educated are a social class detached from the everyday concerns of the majority, and that they dominate political discourse and higher education.

Because "anti-intellectual" can be pejorative, defining specific cases of anti-intellectualism can be troublesome; one can object to specific facets of intellectualism or the application thereof without being dismissive of intellectual pursuits in general. Moreover, allegations of anti-intellectualism can constitute an appeal to authority or an appeal to ridicule that attempts to discredit an opponent rather than specifically addressing his or her arguments.[1]

Anti-intellectualism is a common facet of totalitarian dictatorships to oppress political dissent. The Nazi party's populist rhetoric featured anti-intellectualism as a common motif, including Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf.[citation needed] Perhaps its most extreme political form was during the 1970s in Cambodia under the rule of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, when people were killed for being academics or even for merely wearing eyeglasses (as it suggested literacy) in the Killing Fields.[2]

During the Spanish Civil War and the following fascist dictatorship, General Francisco Franco's civilian repression, the White Terror campaign, killed an estimated 200,000 civilians, targeting heavily writers, artists, teachers and professors. These professionals were seen as probable enemies fostering the cultural and economic changes that Franco had risen in arms to stop, in contrast to Franco's natural ally: a very conservative and unenlightened Catholic Church.

Distrust of intellectuals

Economist Thomas Sowell argues for distinctions between unreasonable and reasonable wariness of intellectuals. Defining intellectuals as "people whose occupations deal primarily with ideas" as distinct from those who apply ideas practically, Sowell argues that there can be good cause for distrust of intellectuals. When working in their fields of expertise, intellectuals have increased knowledge. However, when compared to other careers, Sowell suggests intellectuals have few disincentives for speaking outside their expertise, and are less likely to face the consequences of their errors. For example, a physician is judged by effective treatment, yet might face malpractice lawsuits if he harms a patient. In contrast, a university professor with tenure is less likely to be judged by the effectiveness of his ideas and less likely to face repercussions for his errors:By encouraging, or even requiring, students to take stands where they have neither the knowledge nor the intellectual training to seriously examine complex issues, teachers promote the expression of unsubstantiated opinions, the venting of uninformed emotions, and the habit of acting on those opinions and emotions, while ignoring or dismissing opposing views, without having either the intellectual equipment or the personal experience to weigh one view against another in any serious way.[3]Sowell discusses intellectual influence, labeling schoolteachers as what he calls "intelligentsia" who recruit children, beginning in elementary school, to advocate for or against issues as part of "community service" projects, which will later assist them in the college application process. In this manner, intellectuals participate in other areas where they may possess no prior knowledge at all in order to influence public policy issues. The author argues that as a result, they encourage their students to formulate opinions "without any intellectual training or prior knowledge of those issues, making constraints against falsity few or non-existent."[4]

Similar arguments have been made by others. Historian Paul Johnson[5] argued that a close examination of 20th-century history reveals that intellectuals have championed innumerable disastrous public policies, writing, "beware intellectuals. Not merely should they be kept well away from the levers of power, they should also be objects of suspicion when they seek to offer collective advice." Journalist Tom Wolfe[6] described an intellectual as "a person knowledgeable in one field who speaks out only in others."

Such views form the basis of an episode of the American animation series The Simpsons, "They Saved Lisa's Brain", in which one of the protagonists joins the local branch of Mensa that through a bizarre series of events, subsequently finds itself in complete charge of the local town of Springfield. Considering themselves to be intellectually superior to the rest of the townsfolk, they high-handedly implement a series of ostensibly logical but socially disruptive public policies that antagonize the rest of the town, with disastrous consequences, and are eventually rebuked by Stephen Hawking who appeared as himself.[citation needed]

Authoritarianism

In the 20th century, intellectuals were systematically demoted or expelled from the power structures, and, occasionally, assassinated. In Argentina in 1966, the military dictatorship of Juan Carlos Onganía intervened and dislodged many faculties, leading to a massive brain drain in an event which was called The Night of the Long Police Batons.[7][8] The biochemist César Milstein reports that when the military usurped Argentine government, they declared: "our country would be put in order, as soon as all the intellectuals who were meddling in the region were expelled". In Brazil, the educator Paulo Freire was banished for being ignorant, according to the organizers of the coup d’ État of the moment.[9]Extreme ideological dictatorships, such as the Khmer Rouge regime in Kampuchea (1975–79), killed potential opponents with more than elementary education. In achieving their Year Zero social engineering of Cambodia, they assassinated anyone suspected of "involvement in free-market activities". The suspected Cambodian populace included professionals and almost every educated man and woman, city-dwellers, and people with connections to foreign governments. Doctrinally, the Maoist Khmer Rouge designated the farmers as the true proletariat, as the true representatives of the working class, hence the anti-intellectual purge (cf. Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, 1966–76).

Governmental anti-intellectualism ranges from closing public libraries and public schools, to segregating intellectuals in an Ivory Tower ghetto, to official declarations that intellectuals tend to mental illness, thus facilitating psychiatric imprisonment, then scapegoating to divert popular discontent from the dictatorship (see the USSR and Fascist Italy, cf. Antonio Gramsci).

Moreover, anti-intellectualism is neither always violent, nor oppressive, because most any social group can exercise contempt for intellect, intellectualism, and education. To wit, the Uruguayan writer Jorge Majfud said that "this contempt, that arises from a power installed in the social institutions and from the inferiority complex of its actors, is not a property of "underdeveloped" countries. In fact, it is always the critical intellectuals, writers, or artists who head the top-ten lists of 'The Most Stupid of the Stupid' in the country."[9]

Educational anti-intellectualism

In the English-speaking world, especially in the US, critics like David Horowitz (viz. the David Horowitz Freedom Center), William Bennett, an ex-US secretary of education, and paleoconservative activist Patrick Buchanan, criticize schools and universities as 'intellectualist'.[citation needed]In his book The Campus Wars[10] about the widespread student protests of the late 1960s, philosopher John Searle wrote:

- the two most salient traits of the radical movement are its anti-intellectualism and its hostility to the university as an institution. [...] Intellectuals by definition are people who take ideas seriously for their own sake. Whether or not a theory is true or false is important to them independently of any practical applications it may have. [Intellectuals] have, as Richard Hofstadter has pointed out, an attitude to ideas that is at once playful and pious. But in the radical movement, the intellectual ideal of knowledge for its own sake is rejected. Knowledge is seen as valuable only as a basis for action, and it is not even very valuable there. Far more important than what one knows is how one feels.

Critics have alleged that much of the prevailing philosophy in American academia (i.e., postmodernism, poststructuralism, relativism) are anti-intellectual: "The displacement of the idea that facts and evidence matter by the idea that everything boils down to subjective interests and perspectives is—second only to American political campaigns—the most prominent and pernicious manifestation of anti-intellectualism in our time."[12]

In the notorious Sokal Hoax of the 1990s, physicist Alan Sokal submitted a deliberately preposterous paper to Duke University's Social Text journal to test if, as he later wrote, a leading "culture studies" periodical would "publish an article liberally salted with nonsense if (a) it sounded good and (b) it flattered the editors' ideological preconceptions."[13] Social Text published the paper, seemingly without noting any of the paper's abundant mathematical and scientific errors, leading Sokal to declare that "my little experiment demonstrate[s], at the very least, that some fashionable sectors of the American academic Left have been getting intellectually lazy."

In a 1995 interview, social critic Camille Paglia[14] described academics (including herself) as "a parasitic class," arguing that during widespread social disruption "the only thing holding this culture together will be masculine men of the working class. The cultural elite—women and men—will be pleading for the plumbers and the construction workers."

In America

17th century

In The Powring Out of the Seven Vials (1642), the Puritan John Cotton wrote that 'the more learned and witty you bee, the more fit to act for Satan will you bee. ... Take off the fond doting ... upon the learning of the Jesuites, and the glorie of the Episcopacy, and the brave estates of the Prelates. I say bee not deceived by these pompes, empty shewes, and faire representations of goodly condition before the eyes of flesh and blood, bee not taken with the applause of these persons.'[15] Not every Puritan concurred with Cotton's contempt for secular education; some founded universities such as Harvard, Yale, and Dartmouth.Economist Thomas Sowell[16] argues that American anti-intellectualism can be traced to the early Colonial era, and that wariness of the educated upper-classes is understandable given that America was built, in large part, by people fleeing persecution and brutality at the hands of the educated upper classes. Additionally, rather few intellectuals possessed the practical hands-on skills required to survive in the New World, leading to a deeply rooted suspicion of those who may appear to specialize in "verbal virtuosity" rather than tangible, measurable products or services:

From its colonial beginnings, American society was a "decapitated" society—largely lacking the topmost social layers of European society. The highest elites and the titled aristocracies had little reason to risk their lives crossing the Atlantic and then face the perils of pioneering. Most of the white population of colonial America arrived as indentured servants and the black population as slaves. Later waves of immigrants were disproportionately peasants and proletarians, even when they came from Western Europe [...] The rise of American society to pre-eminence as an economic, political and military power was thus the triumph of the common man and a slap across the face to the presumptions of the arrogant, whether an elite of blood or books.The source, Thomas Sowell, describes the effect the American Revolution had on the development of American government, as established by the Constitution and Bill of Rights. In his opinion, the tendency to "disregard" the impartiality of the law depending upon "who you are" rather than what the author describes as the impartiality of the "supremacy of the law" conflicts with the American creed of the common man. According to Sowell, this fundamental right uniquely distinguishes the American character, forged by "the beaten men of beaten races," from that of the arrogant and privileged elites of the European aristocracy.[17]

19th century

In the history of American anti-intellectualism, modern scholars[citation needed] suggest that 19th-century popular culture is important, because, when most of the populace lived a rural life of manual labour and agricultural work, a 'bookish' education, concerned with the Græco-Roman classics, was perceived as of impractical value, ergo unprofitable—yet Americans, generally, were literate and read Shakespeare for pleasure—thus, the ideal "American" man was technically skilled and successful in his trade, ergo a productive member of society.[citation needed] Culturally, the ideal American was a self-made man whose knowledge derived from life-experience, not an intellectual man, whose knowledge derived from books, formal education, and academic study; thus, in The New Purchase, or Seven and a Half Years in the Far West (1843), the Reverend Bayard R. Hall, A.M., said about frontier Indiana:"We always preferred an ignorant bad man to a talented one, and, hence, attempts were usually made to ruin the moral character of a smart candidate; since, unhappily, smartness and wickedness were supposed to be generally coupled, and [like-wise] incompetence and goodness."[15]Yet, the egghead's worldly redemption was possible if he embraced mainstream mores; thus, in the fiction of O. Henry, a character noted that once an East Coast university graduate 'gets over' his intellectual vanity—no longer thinks himself better than others—he makes just as good a cowboy as any other young man, despite his counterpart being the slow-witted naïf of good heart, a pop culture stereotype from stage shows.

In Europe

Soviet Union

In the first decade after the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks suspected the Tsarist intelligentsia as potentially traitorous of the proletariat, thus, the initial Soviet government comprised men and women without much formal education. Vladimir Lenin derided the old intelligentsia with the expression (roughly translated): 'We have completed no academies' (мы академиев не кончали).[18] Moreover, the deposed propertied classes were termed Lishentsy ("the disenfranchised"), whose children were excluded from education; eventually, some 200 Tsarist intellectuals such as writers, philosophers, scientists, and engineers were deported to Germany on Philosophers' ships in 1922; others were deported to Latvia and to Turkey in 1923.During the revolutionary period, the pragmatic Bolsheviks employed "bourgeois experts" to manage the economy, industry, and agriculture, and so learn from them. After the Russian Civil War (1917–22), to achieve socialism, the USSR (1922–91) emphasised literacy and education in service to modernising the country via an educated working class intelligentsia, rather than an Ivory Tower intelligentsia. During the 1930s and the 1950s, Joseph Stalin replaced Lenin's intelligentsia with a "communist" intelligentsia, loyal to him and with a specifically Soviet world view, thereby producing the most egregious examples of Soviet anti-intellectualism—the pseudoscientific theories of Lysenkoism and Japhetic theory, most damaging to biology and linguistics in that country, by subordinating science to a dogmatic interpretation of Marxism.

Fascism

The idealist philosopher Giovanni Gentile established the intellectual basis of Fascist ideology with the autoctisi (self-realisation) via concrete thinking that distinguished between the good (active) intellectual and the bad (passive) intellectual:

Fascism combats ... not intelligence, but intellectualism... which is... a sickness of the intellect... not a consequence of its abuse, because the intellect cannot be used too much... it derives from the false belief that one can segregate oneself from life.To counter the "passive intellectual" who used his or her intellect abstractly, and therefore was "decadent", he proposed the "concrete thinking" of the active intellectual who applied intellect as praxis—a "man of action", like Fascist Benito Mussolini, versus the decadent Communist intellectual Antonio Gramsci. The passive intellectual stagnates intellect by objectifying ideas, thus establishing them as objects. Hence the Fascist rejection of materialist logic, because it relies upon a priori principles improperly counter-changed with a posteriori ones that are irrelevant to the matter-in-hand in deciding whether or not to act.

—Giovanni Gentile, addressing a Congress of Fascist Culture, Bologna, 30 March 1925

In the praxis of Gentile's concrete thinking criteria, such consideration of the a priori toward the properly a posteriori constitutes impractical, decadent intellectualism. Moreover, this fascist philosophy occurred parallel to Actual Idealism, his philosophic system; he opposed intellectualism for its being disconnected from the active intelligence that gets things done, i.e. thought is killed when its constituent parts are labelled, and thus rendered as discrete entities.[19][20]

Related to this, is the confrontation between the Spanish franquist General, Millán Astray, and the writer Miguel de Unamuno during the Dia de la Raza celebration at the University of Salamanca, in 1936, during the Spanish Civil War. The General exclaimed: ¡Muera la inteligencia! ¡Viva la Muerte! ("Death to intelligence! Long live death!"); the Falangists applauded.[citation needed]

In Asia

China

Imperial China

Qin Shi Huang (246–210 BC), the first Emperor of unified China, consolidated political thought, and power, by suppressing freedom of speech at the suggestion of Chancellor Li Si, who justified such anti-intellectualism by accusing the intelligentsia of falsely praising the emperor, and of dissenting through libel. From 213 to 206 BC, it was generally thought that the works of the Hundred Schools of Thought were incinerated, especially the Shi Jing (Classic of Poetry, c. 1000 BC) and the Shujing (Classic of History, c. 6th century BC). The exceptions were books by Qin historians, and books of Legalism, an early type of totalitarianism—and the Chancellor's philosophic school. (see the Burning of books and burying of scholars). However, upon further inspection of Chinese historical annals such as Shi Ji and Han Shu, this was found not to be the case. The Qin Empire privately kept one copy of each these books in the Imperial Library but publicly ordered that the books should be banned. Those who owned copies were ordered to surrender the books to be burned; those who refused were executed. This eventually led to the loss of most ancient works of literature and philosophy when Xiang Yu burned down the Qin palace in 208BC.People's Republic of China

The Cultural Revolution was a politically violent decade (1966–76) of wide-ranging social engineering of the People's Republic of China by its leader Chairman Mao. After several national policy failures, Mao, to regain public prestige and control of the Communist Party of China (CCP), on 16 May, announced that the Party and Chinese society were permeated with liberal bourgeois elements who meant to restore capitalism to China, and that said people could only be removed with post–Revolutionary class struggle. To that effect, China's youth nationally organised into Red Guards, paramilitaries hunting the liberal bourgeois elements subverting the CCP and Chinese society. The Red Guards acted nationally, purging the country, the military, urban workers, and the leaders of the CCP, until there remained no one politically dangerous to Mao. The Red Guards were particularly brutal in attacking their teachers and professors, causing most schools and universities to be shut down once the Cultural Revolution began. Three years later, in 1969, Mao declared the Cultural Revolution ended; yet the political intrigues continued until 1976, concluding with the arrest of the Gang of Four, the de facto end of the Cultural Revolution.Democratic Kampuchea

When the Communist Party of Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge (1951–81), established their regime as Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979) in Cambodia, their anti-intellectualism idealised the country and demonised the cities to establish agrarian socialism, thus, they emptied cities to purge the Khmer nation of every traitor, enemy of the state, and intellectual, often symbolised by eyeglasses (see the Killing Fields).Ottoman Empire

In the early stages of the Armenian Genocide of 1915, around 2,300 Armenian intellectuals were deported from Constantinople (Istanbul) and subsequently mostly murdered by the Ottoman government.[21] The event has been described by historians as a decapitation strike,[22][23] which intended to deprive the Armenian population of an intellectual leadership and a chance of resistance.[24]