From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the study, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental disorders. These include various affective, behavioural, cognitive and perceptual abnormalities.

Psychiatric assessment typically starts with a mental status examination and the compilation of a case history.

Psychological tests and physical examinations may be conducted, including on occasion the use of neuroimaging or other neurophysiological techniques. Mental disorders are diagnosed in accordance with criteria listed in diagnostic manuals such as the widely used Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), published by the American Psychiatric Association, and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), edited and used by the World Health Organization. The fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5) was published in 2013, and its development was expected to be of significant interest to many medical fields.[1]

The combined treatment of psychiatric medication and psychotherapy has become the most common mode of psychiatric treatment in current practice,[2] but current practice also includes widely ranging variety of other modalities. Treatment may be delivered on an inpatient or outpatient basis, depending on the severity of functional impairment or on other aspects of the disorder in question. Research and treatment within psychiatry, as a whole, are conducted on an interdisciplinary basis, sourcing an array of sub-specialties and theoretical approaches.

Controversy has often surrounded psychiatry, and the term anti-psychiatry was coined by psychiatrist David Cooper in 1967. The anti-psychiatry message is that psychiatric treatments are ultimately more damaging than helpful to patients, and psychiatry's history involves what may now be seen as dangerous treatments (e.g., electroconvulsive therapy, lobotomy).[3] Some ex-patient groups have become anti-psychiatric, often referring to themselves as "survivors".[3]

Etymology

The word psyche comes from the ancient Greek for soul or butterfly.[4] The fluttering insect appears in the coat of arms of Britain's Royal College of Psychiatrists[5]

The term "psychiatry" was first coined by the German physician Johann Christian Reil in 1808 and literally means the 'medical treatment of the soul' (psych- "soul" from Ancient Greek psykhē "soul"; -iatry "medical treatment" from Gk. iātrikos "medical" from iāsthai "to heal"). A medical doctor specializing in psychiatry is a psychiatrist. (For a historical overview, see Timeline of psychiatry.)

Theory and focus

"Psychiatry, more than any other branch of medicine, forces its practitioners to wrestle with the nature of evidence, the validity of introspection, problems in communication, and other long-standing philosophical issues" (Guze, 1992, p.4).

People who specialize in psychiatry often differ from most other mental health professionals and physicians in that they must be familiar with both the social and biological sciences.[7] The discipline studies the operations of different organs and body systems as classified by the patient's subjective experiences and the objective physiology of the patient.[10] Psychiatry treats mental disorders, which are conventionally divided into three very general categories: mental illnesses, severe learning disabilities, and personality disorders.[11] While the focus of psychiatry has changed little over time, the diagnostic and treatment processes have evolved dramatically and continue to do so. Since the late 20th century the field of psychiatry has continued to become more biological and less conceptually isolated from other medical fields.[12]

Scope of practice

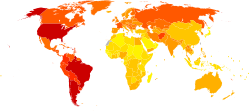

Disability-adjusted life year for neuropsychiatric conditions per 100,000 inhabitants in 2002.

no data

less than 10

10-20

20-30

30-40

40-50

50-60

60-80

80-100

100-120

120-140

140-150

more than 150

Though the medical specialty of psychiatry utilizes research in the field of neuroscience, psychology, medicine, biology, biochemistry, and pharmacology,[13] it has generally been considered a middle ground between neurology and psychology.[14] Unlike other physicians and neurologists, psychiatrists specialize in the doctor–patient relationship and are trained to varying extents in the use of psychotherapy and other therapeutic communication techniques.[14] Psychiatrists also differ from psychologists in that they are physicians and only their residency training (usually 3 to 4 years) is in psychiatry; their undergraduate medical training is identical to all other physicians.[15] Psychiatrists can therefore counsel patients, prescribe medication, order laboratory tests, order neuroimaging, and conduct physical examinations.[16]

Ethics

Like other purveyors of professional ethics, the World Psychiatric Association issues an ethical code to govern the conduct of psychiatrists. The psychiatric code of ethics, first set forth through the Declaration of Hawaii in 1977, has been expanded through a 1983 Vienna update and, in 1996, the broader Madrid Declaration. The code was further revised during the organization's general assembblies in 1999, 2002, 2005, and 2011.[17] The World Psychiatric Association code covers such matters as patient assessment, up-to-date knowledge, the human dignity of incapacitated patients, confidentiality, research ethics, sex selection, euthanasia,[18] organ transplantation, torture,[19][20] the death penalty, media relations, genetics, and ethnic or cultural discrimination.[17]In establishing such ethical codes, the profession has responded to a number of controversies about the practice of psychiatry, for example, surrounding the use of lobotomy and electroconvulsive therapy. Discredited psychiatrists who operated outside the norms of medical ethics include Harry Bailey, Donald Ewen Cameron, Samuel A. Cartwright, Henry Cotton, and Andrei Snezhnevsky.[21][page needed]

Approaches

Psychiatric illnesses can be conceptualised in a number of different ways. The biomedical approach examines signs and symptoms and compares them with diagnostic criteria. Mental illness can be assessed, conversely, through a narrative which tries to incorporate symptoms into a meaningful life history and to frame them as responses to external conditions. Both approaches are important in the field of psychiatry,[22] but have not sufficiently reconciled to settle controversy over either the selection of a psychiatric paradigm or the specification of psychopathology. The notion of a "biopsychosocial model" is often used to underline the multifactorial nature of clinical impairment.[23][24][25] In this notion the word "model" is not used in a strictly scientific way though.[23] Alternatively, a "biocognitive model" acknowledges the physiological basis for the mind's existence, but identifies cognition as an irreducible and independent realm in which disorder may occur.[23][24][25] The biocognitive approach includes a mentalist etiology and provides a natural dualist (i.e. non-spiritual) revision of the biopsychosocial view, reflecting the efforts of Australian psychiatrist Niall McLaren to bring the discipline into scientific maturity in accordance with the paradigmatic standards of philosopher Thomas Kuhn.[23][24][25]Subspecialties

Various subspecialties and/or theoretical approaches exist which are related to the field of psychiatry. They include the following:- Addiction psychiatry; focuses on evaluation and treatment of individuals with alcohol, drug, or other substance-related disorders, and of individuals with dual diagnosis of substance-related and other psychiatric disorders.

- Biological psychiatry; an approach to psychiatry that aims to understand mental disorders in terms of the biological function of the nervous system.

- Child and adolescent psychiatry; the branch of psychiatry that specializes in work with children, teenagers, and their families.

- Community psychiatry; an approach that reflects an inclusive public health perspective and is practiced in community mental health services.[26]

- Cross-cultural psychiatry; a branch of psychiatry concerned with the cultural and ethnic context of mental disorder and psychiatric services.

- Emergency psychiatry; the clinical application of psychiatry in emergency settings.

- Forensic psychiatry; the interface between law and psychiatry.

- Geriatric psychiatry; a branch of psychiatry dealing with the study, prevention, and treatment of mental disorders in humans with old age.

- Liaison psychiatry; the branch of psychiatry that specializes in the interface between other medical specialties and psychiatry.

- Military psychiatry; covers special aspects of psychiatry and mental disorders within the military context.

- Neuropsychiatry; branch of medicine dealing with mental disorders attributable to diseases of the nervous system.

- Social psychiatry; a branch of psychiatry that focuses on the interpersonal and cultural context of mental disorder and mental well-being.

In the United States, psychiatry is one of the specialties which qualify for further education and board-certification in pain medicine, palliative medicine, and sleep medicine.

Industry and academia

Practitioners

All physicians can diagnose mental disorders and prescribe treatments utilizing principles of psychiatry. Psychiatrists are either: 1) clinicians who specialize in psychiatry and are certified in treating mental illness;[27] or (2) scientists in the academic field of psychiatry who are qualified as research doctors in this field. Psychiatrists may also go through significant training to conduct psychotherapy, psychoanalysis and cognitive behavioral therapy, but it is their training as physicians that differentiates them from other mental health professionals.[27]Research

Psychiatric research is, by its very nature, interdisciplinary; combining social, biological and psychological perspectives in attempt to understand the nature and treatment of mental disorders.[28] Clinical and research psychiatrists study basic and clinical psychiatric topics at research institutions and publish articles in journals.[13][29][30][31] Under the supervision of institutional review boards, psychiatric clinical researchers look at topics such as neuroimaging, genetics, and psychopharmacology in order to enhance diagnostic validity and reliability, to discover new treatment methods, and to classify new mental disorders.[32]Clinical application

Diagnostic systems

See also Diagnostic classification and rating scales used in psychiatryPsychiatric diagnoses take place in a wide variety of settings and are performed by many different health professionals. Therefore, the diagnostic procedure may vary greatly based upon these factors. Typically, though, a psychiatric diagnosis utilizes a differential diagnosis procedure where a mental status examination and physical examination is conducted, with pathological, psychopathological or psychosocial histories obtained, and sometimes neuroimages or other neurophysiological measurements are taken, or personality tests or cognitive tests administered.[33][34][35][36][37] In some cases, a brain scan might be used to rule out other medical illnesses, but at this time relying on brain scans alone cannot accurately diagnose a mental illness or tell the risk of getting a mental illness in the future.[38] A few psychiatrists are beginning to utilize genetics during the diagnostic process but on the whole this remains a research topic.[39][40][41]

Diagnostic manuals

Three main diagnostic manuals used to classify mental health conditions are in use today. The ICD-10 is produced and published by the World Health Organization, includes a section on psychiatric conditions, and is used worldwide.[42] The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, produced and published by the American Psychiatric Association, is primarily focused on mental health conditions and is the main classification tool in the United States.[43] It is currently in its fourth revised edition and is also used worldwide.[43] The Chinese Society of Psychiatry has also produced a diagnostic manual, the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders.[44]The stated intention of diagnostic manuals is typically to develop replicable and clinically useful categories and criteria, to facilitate consensus and agreed upon standards, whilst being atheoretical as regards etiology.[43][45]However, the categories are nevertheless based on particular psychiatric theories and data; they are broad and often specified by numerous possible combinations of symptoms, and many of the categories overlap in symptomology or typically occur together.[46] While originally intended only as a guide for experienced clinicians trained in its use, the nomenclature is now widely used by clinicians, administrators and insurance companies in many countries.[47]

The DSM has attracted praise for standardizing psychiatric diagnostic categories and criteria. It has also attracted controversy and criticism. Some critics argue that the DSM represents an unscientific system that enshrines the opinions of a few powerful psychiatrists. There are ongoing issues concerning the validity and reliability of the diagnostic categories; the reliance on superficial symptoms; the use of artificial dividing lines between categories and from 'normality'; possible cultural bias; medicalization of human distress and financial conflicts of interest, including with the practice of psychiatrists and with the pharmaceutical industry; political controversies about the inclusion or exclusion of diagnoses from the manual, in general or in regard to specific issues; and the experience of those who are most directly affected by the manual by being diagnosed, including the consumer/survivor movement.[48][49][50][51] The publication of the DSM, with tightly guarded copyrights, now makes APA over $5 million a year, historically adding up to over $100 million.[52]

Treatment

General considerations

Individuals with mental health conditions are commonly referred to as patients but may also be called clients, consumers, or service recipients. They may come under the care of a psychiatric physician or other psychiatric practitioners by various paths, the two most common being self-referral or referral by a primary-care physician. Alternatively, a person may be referred by hospital medical staff, by court order, involuntary commitment, or, in the UK and Australia, by sectioning under a mental health law.

Persons who undergo a psychiatric assessment are evaluated by a psychiatrist for their mental and physical condition. This usually involves interviewing the person and often obtaining information from other sources such as other health and social care professionals, relatives, associates, law enforcement personnel, emergency medical personnel, and psychiatric rating scales. A mental status examination is carried out, and a physical examination is usually performed to establish or exclude other illnesses that may be contributing to the alleged psychiatric problems. A physical examination may also serve to identify any signs of self-harm; this examination is often performed by someone other than the psychiatrist, especially if blood tests and medical imaging are performed.

Like most medications, psychiatric medications can cause adverse effects in patients, and some require ongoing therapeutic drug monitoring, for instance full blood counts serum drug levels, renal function, liver function, and/or thyroid function. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is sometimes administered for serious and disabling conditions, such as those unresponsive to medication. The efficacy[53][54] and adverse effects of psychiatric drugs may vary from patient to patient.

For many years, controversy has surrounded the use of involuntary treatment and use of the term "lack of insight" in describing patients. Mental health laws vary significantly among jurisdictions, but in many cases, involuntary psychiatric treatment is permitted when there is deemed to be a risk to the patient or others due to the patient's illness. Involuntary treatment refers to treatment that occurs based on the treating physician's recommendations without requiring consent from the patient.[55]

Inpatient treatment

Psychiatric treatments have changed over the past several decades. In the past, psychiatric patients were often hospitalized for six months or more, with some cases involving hospitalization for many years. Today, people receiving psychiatric treatment are more likely to be seen as outpatients. If hospitalization is required, the average hospital stay is around one to two weeks, with only a small number receiving long-term hospitalization.[citation needed]Psychiatric inpatients are people admitted to a hospital or clinic to receive psychiatric care. Some are admitted involuntarily, perhaps committed to a secure hospital, or in some jurisdictions to a facility within the prison system. In many countries including the USA and Canada, the criteria for involuntary admission vary with local jurisdiction. They may be as broad as having a mental health condition, or as narrow as being an immediate danger to themselves and/or others. Bed availability is often the real determinant of admission decisions to hard pressed public facilities. European Human Rights legislation restricts detention to medically certified cases of mental disorder, and adds a right to timely judicial review of detention.[citation needed]

Patients may be admitted voluntarily if the treating doctor considers that safety isn't compromised by this less restrictive option. Inpatient psychiatric wards may be secure (for those thought to have a particular risk of violence or self-harm) or unlocked/open. Some wards are mixed-sex whilst same-sex wards are increasingly favored to protect women inpatients. Once in the care of a hospital, people are assessed, monitored, and often given medication and care from a multidisciplinary team, which may include physicians, pharmacists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists, psychotherapists, psychiatric social workers, occupational therapists and social workers. If a person receiving treatment in a psychiatric hospital is assessed as at particular risk of harming themselves or others, they may be put on constant or intermittent one-to-one supervision, and may be physically restrained or medicated. People on inpatient wards may be allowed leave for periods of time, either accompanied or on their own.[56]

In many developed countries there has been a massive reduction in psychiatric beds since the mid 20th century, with the growth of community care. Standards of inpatient care remain a challenge in some public and private facilities, due to levels of funding, and facilities in developing countries are typically grossly inadequate for the same reason. Even in developed countries, programs in public hospitals vary widely. Some may offer structured activities and therapies offered from many perspectives while others may only have the funding for medicating and monitoring patients. This may be problematic in that the maximum amount of therapeutic work might not actually take place in the hospital setting. This is why hospitals are increasingly used in limited situations and moments of crises where patients are a direct threat to themselves or others. Alternatives to psychiatric hospitals that may actively offer more therapeutic approaches include rehabilitation centers or "rehab" as popularly termed.[citation needed]

Outpatient treatment

Outpatient treatment involves periodic visits to a psychiatrist for consultation in his or her office, or at a community-based outpatient clinic. Initial appointments, at which the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric assessment or evaluation of the patient, are typically 45 to 75 minutes in length. Follow-up appointments are generally shorter in duration, i.e., 15 to 30 minutes, with a focus on making medication adjustments, reviewing potential medication interactions, considering the impact of other medical disorders on the patient's mental and emotional functioning, and counseling patients regarding changes they might make to facilitate healing and remission of symptoms (e.g., exercise, cognitive therapy techniques, sleep hygiene—to name just a few). The frequency with which a psychiatrist sees people in treatment varies widely, from once a week to twice a year, depending on the type, severity and stability of each person's condition, and depending on what the clinician and patient decide would be best.Increasingly, psychiatrists are limiting their practices to psychopharmacology (prescribing medications), as opposed to previous practice in which a psychiatrist would provide traditional 50-minute psychotherapy sessions, of which psychopharmacology would be a part, but most of the consultation sessions consisted of "talk therapy." This shift began in the early 1980s and accelerated in the 1990s and 2000s.[57] A major reason for this change was the advent of managed care insurance plans, which began to limit reimbursement for psychotherapy sessions provided by psychiatrists. The underlying assumption was that psychopharmacology was at least as effective as psychotherapy, and it could be delivered more efficiently because less time is required for the appointment.[58][59][60][61][62][63] For example, most psychiatrists schedule three or four follow-up appointments per hour, as opposed to seeing one patient per hour in the traditional psychotherapy model.[a]

Because of this shift in practice patterns, psychiatrists often refer patients whom they think would benefit from psychotherapy to other mental health professionals, e.g., clinical social workers and psychologists.[69]

History

Ancient

Specialty in psychiatry can be traced in Ancient India. The oldest texts on psychiatry include the ayurvedic text, Charaka Samhita.[70][71] Some of the first hospitals for curing mental illness were established during 3rd century BCE.[72]During the 5th century BCE, mental disorders, especially those with psychotic traits, were considered supernatural in origin,[73] a view which existed throughout ancient Greece and Rome.[73] The beginning of psychiatry as a medical specialty is dated to the middle of the nineteenth century,[74] although one may trace its germination to the late eighteenth century.

Some of the early manuals about mental disorders were created by the Greeks.[74] In the 4th century BCE, Hippocrates theorized that physiological abnormalities may be the root of mental disorders.[73] In 4th to 5th Century B.C. Greece, Hippocrates wrote that he visited Democritus and found him in his garden cutting open animals. Democritus explained that he was attempting to discover the cause of madness and melancholy. Hippocrates praised his work. Democritus had with him a book on madness and melancholy.[75]

Religious leaders often turned to versions of exorcism to treat mental disorders often utilizing methods that many consider to be cruel and/or barbaric methods.[73]

Middle Ages

Specialist hospitals were built in Baghdad in 705 AD,[76] followed by Fes in the early 8th century, and Cairo in 800 AD.[citation needed]Physicians who wrote on mental disorders and their treatment in the Medieval Islamic period included Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Rhazes), the Arab physician Najab ud-din Muhammad[citation needed], and Abu Ali al-Hussain ibn Abdallah ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna.[77][78][79]

Specialist hospitals were built in medieval Europe from the 13th century to treat mental disorders but were utilized only as custodial institutions and did not provide any type of treatment.[80]

Early modern period

Founded in the 13th century, Bethlem Royal Hospital in London was one of the oldest lunatic asylums.[80] In the late 17th century, privately run asylums for the insane began to proliferate and expand in size. Already in 1632 it was recorded that Bethlem Royal Hospital, London had "below stairs a parlor, a kitchen, two larders, a long entry throughout the house, and 21 rooms wherein the poor distracted people lie, and above the stairs eight rooms more for servants and the poor to lie in".[81] Inmates who were deemed dangerous or disturbing were chained, but Bethlem was an otherwise open building for its inhabitants to roam around its confines and possibly throughout the general neighborhood in which the hospital was situated.[82] In 1676, Bethlem expanded into newly built premises at Moorfields with a capacity for 100 inmates.[83]:155[84]:27

In 1713 the Bethel Hospital Norwich was opened, the first purpose-built asylum in England, founded by Mary Chapman.[85]

In 1621, Oxford University mathematician, astrologer, and scholar Robert Burton published one of the earliest treatises on mental illness, The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up. Burton thought that there was "no greater cause of melancholy than idleness, no better cure than business." Unlike English philosopher of science Francis Bacon, Burton argued that knowledge of the mind, not natural science, is humankind's greatest need.[86]

In 1656, Louis XIV of France created a public system of hospitals for those suffering from mental disorders, but as in England, no real treatment was applied.[87]

Humanitarian reform

Dr. Philippe Pinel at the Salpêtrière, 1795 by Tony Robert-Fleury. Pinel ordering the removal of chains from patients at the Paris Asylum for insane women.

During the Enlightenment attitudes towards the mentally ill began to change. It came to be viewed as a disorder that required compassionate treatment that would aid in the rehabilitation of the victim. In 1758 English physician William Battie wrote his Treatise on Madness on the management of mental disorder. It was a critique aimed particularly at the Bethlem Hospital, where a conservative regime continued to use barbaric custodial treatment. Battie argued for a tailored management of patients entailing cleanliness, good food, fresh air, and distraction from friends and family. He argued that mental disorder originated from dysfunction of the material brain and body rather than the internal workings of the mind.[88][89]

Thirty years later, then ruling monarch in England George III was known to be suffering from a mental disorder.[73] Following the King's remission in 1789, mental illness came to be seen as something which could be treated and cured.[73] The introduction of moral treatment was initiated independently by the French doctor Philippe Pinel and the English Quaker William Tuke.[73]

In 1792 Pinel became the chief physician at the Bicêtre Hospital. In 1797, Pussin first freed patients of their chains and banned physical punishment, although straitjackets could be used instead.[90][91]

Patients were allowed to move freely about the hospital grounds, and eventually dark dungeons were replaced with sunny, well-ventilated rooms. Pussin and Pinel's approach was seen as remarkably successful and they later brought similar reforms to a mental hospital in Paris for female patients, La Salpetrière. Pinel's student and successor, Jean Esquirol (1772–1840), went on to help establish 10 new mental hospitals that operated on the same principles.

There was an emphasis on the selection and supervision of attendants in order to establish a suitable setting to facilitate psychological work, and particularly on the employment of ex-patients as they were thought most likely to refrain from inhumane treatment while being able to stand up to pleading, menaces, or complaining.[92]

William Tuke led the development of a radical new type of institution in northern England, following the death of a fellow Quaker in a local asylum in 1790.[93]:84–85 [94]:30 [95] In 1796, with the help of fellow Quakers and others, he founded the York Retreat, where eventually about 30 patients lived as part of a small community in a quiet country house and engaged in a combination of rest, talk, and manual work. Rejecting medical theories and techniques, the efforts of the York Retreat centered around minimizing restraints and cultivating rationality and moral strength. The entire Tuke family became known as founders of moral treatment.[96]

William Tuke's grandson, Samuel Tuke, published an influential work in the early 19th century on the methods of the retreat; Pinel's Treatise On Insanity had by then been published, and Samuel Tuke translated his term as "moral treatment". Tuke's Retreat became a model throughout the world for humane and moral treatment of patients suffering from mental disorders.[96] The York Retreat inspired similar institutions in the United States, most notably the Brattleboro Retreat and the Hartford Retreat (now The Institute of Living).

Although Tuke, Pinel and others had tried to do away with physical restraint, it remained widespread into the 19th century. At the Lincoln Asylum in England, Robert Gardiner Hill, with the support of Edward Parker Charlesworth, pioneered a mode of treatment that suited "all types" of patients, so that mechanical restraints and coercion could be dispensed with — a situation he finally achieved in 1838. In 1839 Sergeant John Adams and Dr. John Conolly were impressed by the work of Hill, and introduced the method into their Hanwell Asylum, by then the largest in the country. Hill's system was adapted, since Conolly was unable to supervise each attendant as closely as Hill had done. By September 1839, mechanical restraint was no longer required for any patient.[97][98]

Phrenology

Main article: Phrenology

William A. F. Browne was an influential reformer of the lunatic asylum in the mid-19th century, and an advocate of the new 'science' of phrenology.

Scotland's Edinburgh medical school of the eighteenth century developed an interest in mental illness, with influential teachers including William Cullen (1710–1790) and Robert Whytt (1714–1766) emphasising the clinical importance of psychiatric disorders. In 1816, the phrenologist Johann Spurzheim (1776–1832) visited Edinburgh and lectured on his craniological and phrenological concepts; the central concepts of the system were that the brain is the organ of the mind and that human behaviour can be usefully understood in neurological rather than philosophical or religious terms. Phrenologists also laid stress on the modularity of mind.

Some of the medical students, including William A. F. Browne (1805–1885), responded very positively to this materialist conception of the nervous system and, by implication, of mental disorder. George Combe (1788–1858), an Edinburgh solicitor, became an unrivalled exponent of phrenological thinking, and his brother, Andrew Combe (1797–1847), who was later appointed a physician to Queen Victoria, wrote a phrenological treatise entitled Observations on Mental Derangement (1831). They also founded the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1820.

Institutionalization

The modern era of institutionalized provision for the care of the mentally ill, began in the early 19th century with a large state-led effort. Public mental asylums were established in Britain after the passing of the 1808 County Asylums Act. This empowered magistrates to build rate-supported asylums in every county to house the many 'pauper lunatics'. Nine counties first applied, and the first public asylum opened in 1812 in Nottinghamshire. Parliamentary Committees were established to investigate abuses at private madhouses like Bethlem Hospital - its officers were eventually dismissed and national attention was focused on the routine use of bars, chains and handcuffs and the filthy conditions the inmates lived in. However, it was not until 1828 that the newly appointed Commissioners in Lunacy were empowered to license and supervise private asylums.

Lord Shaftesbury, a vigorous campaigner for the reform of lunacy law in England, and the Head of the Lunacy Commission for 40 years.

The Lunacy Act 1845 was an important landmark in the treatment of the mentally ill, as it explicitly changed the status of mentally ill people to patients who required treatment. The Act created the Lunacy Commission, headed by Lord Shaftesbury, to focus on lunacy legislation reform.[99] The Commission was made up of eleven Metropolitan Commissioners who were required to carry out the provisions of the Act;[100][full citation needed] the compulsory construction of asylums in every county, with regular inspections on behalf of the Home Secretary. All asylums were required to have written regulations and to have a resident qualified physician.[100] A national body for asylum superintendents - the Medico-Psychological Association - was established in 1866 under the Presidency of William A. F. Browne, although the body appeared in an earlier form in 1841.[101]

In 1838, France enacted a law to regulate both the admissions into asylums and asylum services across the country. Édouard Séguin developed a systematic approach for training individuals with mental deficiencies,[102] and, in 1839, he opened the first school for the severely retarded. His method of treatment was based on the assumption that the mentally deficient did not suffer from disease.[103]

In the United States, the erection of state asylums began with the first law for the creation of one in New York, passed in 1842. The Utica State Hospital was opened approximately in 1850. The creation of this hospital, as of many others, was largely the work of Dorothea Lynde Dix, whose philanthropic efforts extended over many states, and in Europe as far as Constantinople. Many state hospitals in the United States were built in the 1850s and 1860s on the Kirkbride Plan, an architectural style meant to have curative effect.[104]

At the turn of the century, England and France combined had only a few hundred individuals in asylums.[105] By the late 1890s and early 1900s, this number had risen to the hundreds of thousands. However, the idea that mental illness could be ameliorated through institutionalization was soon disappointed.[106] Psychiatrists were pressured by an ever increasing patient population.[106] The average number of patients in asylums kept on growing.[106] Asylums were quickly becoming almost indistinguishable from custodial institutions,[107] and the reputation of psychiatry in the medical world had hit an extreme low.[108]

Scientific advances

In the early 1800s, psychiatry made advances in the diagnosis of mental illness by broadening the category of mental disease to include mood disorders, in addition to disease level delusion or irrationality.[109] The term psychiatry (Greek "ψυχιατρική", psychiatrikē) which comes from the Greek "ψυχή" (psychē: "soul or mind") and "ιατρός" (iatros: "healer") was coined by Johann Christian Reil in 1808.[110][unreliable source?][111] Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol, a student of Pinel, defined lypemania as an 'affective monomania' (excessive attention to a single thing). This was an early diagnosis of depression.[109][112]

The 20th century introduced a new psychiatry into the world. Different perspectives of looking at mental disorders began to be introduced. The career of Emil Kraepelin reflects the convergence of different disciplines in psychiatry.[113] Kraepelin initially was very attracted to psychology and ignored the ideas of anatomical psychiatry.[113] Following his appointment to a professorship of psychiatry and his work in a university psychiatric clinic, Kraepelin's interest in pure psychology began to fade and he introduced a plan for a more comprehensive psychiatry.[114] Kraepelin began to study and promote the ideas of disease classification for mental disorders, an idea introduced by Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum.[115] The initial ideas behind biological psychiatry, stating that the different mental disorders were all biological in nature, evolved into a new concept of "nerves" and psychiatry became a rough approximation of neurology and neuropsychiatry.[116] However, Kraepelin was criticized for considering schizophrenia as a biological illness in the absence of any detectable histologic or anatomic abnormalities.[117]:221 While Kraepelin tried to find organic causes of mental illness, he adopted many theses of positivist medicine, but he favoured the precision of nosological classification over the indefiniteness of etiological causation as his basic mode of psychiatric explanation.[118]

Following Sigmund Freud's pioneering work, ideas stemming from psychoanalytic theory also began to take root in psychiatry.[119] The psychoanalytic theory became popular among psychiatrists because it allowed the patients to be treated in private practices instead of warehoused in asylums.[119] By the 1970s the psychoanalytic school of thought had become marginalized within the field.[119]

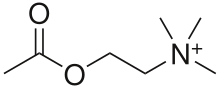

Biological psychiatry reemerged during this time. Psychopharmacology became an integral part of psychiatry starting with Otto Loewi's discovery of the neuromodulatory properties of acetylcholine; thus identifying it as the first-known neurotransmitter.[120] Neuroimaging was first utilized as a tool for psychiatry in the 1980s.[121] The discovery of chlorpromazine's effectiveness in treating schizophrenia in 1952 revolutionized treatment of the disorder,[122] as did lithium carbonate's ability to stabilize mood highs and lows in bipolar disorder in 1948.[123] Psychotherapy was still utilized, but as a treatment for psychosocial issues.[124] In the 1920s and 1930s, most asylum and academic psychiatrists in Europe believed that manic depressive disorder and schizophrenia were inherited, but in the decades after World War II, the conflation of genetics with Nazi racist ideology thoroughly discredited genetics.[125]

Now genetics are once again thought by some to play a role in mental illness.[120][126][unreliable medical source?] Geneticist Müller-Hill is quoted as saying "Genes are not destiny, they may give an individual a pre-disposition toward a disorder, for example, but that only means they are more likely than others to have it. It (mental illness) is not a certainty.”[127][unreliable medical source?] Molecular biology opened the door for specific genes contributing to mental disorders to be identified.[120]

Deinstitutionalization

Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates (1961), written by sociologist Erving Goffman,[128][129][better source needed] examined the social situation of mental patients in the hospital.[130] Based on his participant observation field work, the book developed the theory of the "total institution" and the process by which it takes efforts to maintain predictable and regular behavior on the part of both "guard" and "captor". The book suggested that many of the features of such institutions serve the ritual function of ensuring that both classes of people know their function and social role, in other words of "institutionalizing" them. Asylums was a key text in the development of deinstitutionalisation.[131]In 1963, US president John F. Kennedy introduced legislation delegating the National Institute of Mental Health to administer Community Mental Health Centers for those being discharged from state psychiatric hospitals.[132] Later, though, the Community Mental Health Centers focus shifted to providing psychotherapy for those suffering from acute but less serious mental disorders.[132] Ultimately there were no arrangements made for actively following and treating severely mentally ill patients who were being discharged from hospitals.[132] Some of those suffering from mental disorders drifted into homelessness or ended up in prisons and jails.[132][133] Studies found that 33% of the homeless population and 14% of inmates in prisons and jails were already diagnosed with a mental illness.[132][134]

In 1973, psychologist David Rosenhan published the Rosenhan experiment, a study with results that led to questions about the validity of psychiatric diagnoses.[135] Critics such as Robert Spitzer placed doubt on the validity and credibility of the study, but did concede that the consistency of psychiatric diagnoses needed improvement.[136]

Psychiatry, like most medical specialties has a continuing, significant need for research into its diseases, classifications and treatments.[137] Psychiatry adopts biology's fundamental belief that disease and health are different elements of an individual's adaptation to an environment.[138] But psychiatry also recognizes that the environment of the human species is complex and includes physical, cultural, and interpersonal elements.[138] In addition to external factors, the human brain must contain and organize an individual's hopes, fears, desires, fantasies and feelings.[138] Psychiatry's difficult task is to bridge the understanding of these factors so that they can be studied both clinically and physiologically.[138]

Controversy

Power imbalance

Too often it is felt institutions have too much power, concerns of patients or their relatives are ignored.[139]Psychiatric nurses impose decisions, are reluctant to share information and feel they know best. Only a minority of staff involve patients in decision making.[140] Client empowerment can improve power imbalance. Psychiatrically ill patients are at risk of abuse and discrimination in the mental health system and also the primary care sector. Studies are needed to determine whether power imbalance leads to abuse.[141] Some degree of power imbalance appears inevitable since some patients lack decision making capacity but even then patients benefit from being impowered within their limits. For example a patient felt lethargic in mornings due to medication she was required to take. She was allowed to stay in bed and miss breakfast as she wanted.[142][better source needed] Multidisciplinary teams benefit patients to the extent that professionals with a range of different expertise are caring for them. There is also a problem because patients who complain about the way they are treated face a group rather than one individual opposing them.[143]

Mental illness myth

Vienna's Narrenturm — German for "fools' tower" — was one of the earliest buildings specifically designed as a "madhouse". It was built in 1784.

Since the 1960s there have been many challenges to the concept of mental illness itself. Thomas Szasz wrote The Myth of Mental Illness (1960) which said that mental illnesses are not real in the sense that cancers are real. Except for a few identifiable brain diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, there are "neither biological or chemical tests nor biopsy or necropsy findings" for verifying or falsifying psychiatric diagnoses. There are no objective methods for detecting the presence or absence of mental disease. Szasz argued that mental illness was a myth used to disguise moral conflicts. He has said "serious persons ought not to take psychiatry seriously -- except as a threat to reason, responsibility and liberty".[144]

Sociologists such as Erving Goffman and Thomas Scheff said that mental illness was merely another example of how society labels and controls non-conformists; behavioural psychologists challenged psychiatry's fundamental reliance on unobservable phenomena; and gay rights activists criticised the APA's listing of homosexuality as a mental disorder. A widely publicised study by Rosenhan in Science was viewed as an attack on the efficacy of psychiatric diagnosis.[145]

These critiques targeted the heart of psychiatry:

They suggested that psychiatry's core concepts were myths, that psychiatry's relationship to medical science had only historical connections, that psychiatry was more aptly characterised as a vast system of coercive social management, and that its paradigmatic practice methods (the talking cure and psychiatric confinement) were ineffective or worse.[21]:136

Medicalization of normality

For many years, some psychiatrists (such as Peter Breggin, Paula Caplan, Thomas Szasz) and outside critics (such as Stuart A. Kirk) have "been accusing psychiatry of engaging in the systematic medicalization of normality". More recently these concerns have come from insiders who have worked for and promoted the APA (e.g., Robert Spitzer, Allen Frances).[21]:185 In 2013, Allen Frances said that "psychiatric diagnosis still relies exclusively on fallible subjective judgments rather than objective biological tests".[146][147]Medicalization of deviance

The concept of medicalization is created by sociologists and used for explaining how medical knowledge is applied to a series of behaviors, over which medicine exerts control, although those behaviors are not self-evidently medical or biological.[148] According to Kittrie, a number of phenomena considered "deviant", such as alcoholism, drug addiction and mental illness, were originally considered as moral, then legal, and now medical problems.[149]:1[150] As a result of these perceptions, peculiar deviants were subjected to moral, then legal, and now medical modes of social control.[149]:1 Similarly, Conrad and Schneider concluded their review of the medicalization of deviance by supposing that three major paradigms may be identified that have reigned over deviance designations in different historical periods: deviance as sin; deviance as crime; and deviance as sickness.[149]:1[151]:36 According to Franco Basaglia and his followers, whose approach pointed out the role of psychiatric institutions in the control and medicalization of deviant behaviors and social problems, psychiatry is used as the provider of scientific support for social control to the existing establishment, and the ensuing standards of deviance and normality brought about repressive views of discrete social groups.[152]:70 As scholars have long argued, governmental and medical institutions code menaces to authority as mental diseases during political disturbances.[153]Political abuse

Psychiatrists have been involved in human rights abuses in states across the world when the definitions of mental disease were expanded to include political disobedience.[154] As scholars have long argued, governmental and medical institutions code menaces to authority as mental diseases during political disturbances.[153] Nowadays, in many countries, political prisoners are sometimes confined and abused in mental institutions.[155]:3 Psychiatric confinement of sane people is a particularly pernicious form of repression.[156]Psychiatry possesses a built-in capacity for abuse that is greater than in other areas of medicine.[157] The diagnosis of mental disease allows the state to hold persons against their will and insist upon therapy in their interest and in the broader interests of society.[157] In addition, receiving a psychiatric diagnosis can in itself be regarded as oppressive.[158]:94 In a monolithic state, psychiatry can be used to bypass standard legal procedures for establishing guilt or innocence and allow political incarceration without the ordinary odium attaching to such political trials.[157] The use of hospitals instead of jails prevents the victims from receiving legal aid before the courts, makes indefinite incarceration possible, discredits the individuals and their ideas.[159]:29 In that manner, whenever open trials are undesirable, they are avoided.[159]:29

Examples of political abuse of the power, entrusted in physicians and particularly psychiatrists, are abundant in history and seen during the Nazi era and the Soviet rule when political dissenters were labeled as “mentally ill” and subjected to inhumane “treatments.”[160] In the period from the 1960s up to 1986, abuse of psychiatry for political purposes was reported to be systematic in the Soviet Union, and occasional in other Eastern European countries such as Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia.[157] The practice of incarceration of political dissidents in mental hospitals in Eastern Europe and the former USSR damaged the credibility of psychiatric practice in these states and entailed strong condemnation from the international community.[161] Political abuse of psychiatry also takes place in the People's Republic of China[162] and in Russia.[163] Psychiatric diagnoses such as the diagnosis of ‘sluggish schizophrenia’ in political dissidents in the USSR were used for political purposes.[164]:77

Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was one treatment that the anti-psychiatry movement wanted eliminated.[165] Their arguments were that ECT damages the brain,[165] and was used as punishment or as a threat to keep the patients "in line".[165] Since then, ECT has improved considerably,[166] and is performed under general anaesthetic in a medically supervised environment.[167]The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends ECT for the short term treatment of severe, treatment-resistant depression, and advises against its use in schizophrenia.[168][169] According to the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, ECT is more efficacious for the treatment of depression than antidepressants, with a response rate of 90% in first line treatment and 50-60% in treatment-resistant patients.[170] On the other hand, a 2010 literature review concluded that ECT had minimal benefits for people with depression and schizophrenia.[171]

The most common side effects include headache, muscle soreness, confusion, and temporary loss of recent memory.[167][172] There is no credible evidence supporting claims that ECT causes structural damage to the brain.[170]

Deinstitutionalisation

The prevalence of psychiatric medication helped initiate deinstitutionalization,[132] the process of discharging patients from psychiatric hospitals to the community.[173] The pressure from the anti-psychiatry movements and the ideology of community treatment from the medical arena helped sustain deinstitutionalization.[132] Thirty-three years after deinstitutionalization started in the United States, only 19% of the patients in state hospitals remained.[132] Mental health professionals envisioned a process wherein patients would be discharged into communities where they could participate in a normal life while living in a therapeutic atmosphere.[132]Psychiatrists were criticized, however, for failing to develop community-based support and treatment. Community-based facilities were not available because of the political infighting between in-patient and community-based social services, and an unwillingness by social services to dispense funding to provide adequately for patients to be discharged into community-based facilities.

Pharmaceutical industry ties

Psychiatry has greatly benefitted by advances in pharmacotherapy.[3]:110–112[174] However, the close relationship between those prescribing psychiatric medication and pharmaceutical companies, and the risk of a conflict of interest,[174] is also a source of concern. This marketing by the pharmaceutical industry has an influence on practicing psychiatrists, which has an impact on prescription.[174] Child psychiatry is one of the area's in which prescription has grown massively. In the past, it was rare, but nowadays child psychiatrists on a regular basis prescribe psychotropic drugs for children, for instance Ritalin.[3]:110–112Several prominent academic psychiatrists have refused to disclose financial conflicts of interest, which further undermines public trust in psychiatry.[175] Charles Grassley led a 2008 Congressional Investigation which found that well-known university psychiatrists (such as Joseph Biederman, Charles Nemeroff, and Alan Schatzberg), who had promoted psychoactive drugs, had violated federal and university regulations by secretly receiving large sums of money from the pharmaceutical companies which made the drugs.[21]:21

In an effort to reduce the potential for hidden conflicts of interest between researchers and pharmaceutical companies, the US Government issued a mandate in 2012 requiring that drug manufacturers receiving funds under the Medicare and Medicaid programs collect data, and make public, all gifts to doctors and hospitals.[21]:317

Prisoner experimentation

Prisoners in psychiatric hospitals have been the subjects of experiments involving new medications. Vladimir Khailo of the USSR was an individual exposed to such treatment in the 1980s.[176] However, the involuntary treatment of prisoners by use of psychiatric drugs has not been limited to Khailo, nor the USSR.Anti-psychiatry

Controversy has often surrounded psychiatry,[3] and the anti-psychiatry message is that psychiatric treatments are ultimately more damaging than helpful to patients. Psychiatry is often thought to be a benign medical practice, but at times is seen by some as a coercive instrument of oppression. Psychiatry is seen to involve an unequal power relationship between doctor and patient, and advocates of anti-psychiatry claim a subjective diagnostic process, leaving much room for opinions and interpretations.[3][177] Every society, including liberal Western society, permits compulsory treatment of mental patients.[3] The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes that "poor quality services and human rights violations in mental health and social care facilities are still an everyday occurrence in many places", but has recently taken steps to improve the situation globally.[178]Psychiatry's history involves what some view as dangerous treatments.[3] Electroconvulsive therapy is one of these, which was used widely between the 1930s and 1960s and is still in use today. The brain surgery procedure lobotomy is another practice that was ultimately seen as too invasive and brutal.[177] In the US, between 1939 and 1951, over 50,000 lobotomy operations were performed in mental hospitals. Valium and other sedatives have arguably been over-prescribed, leading to a claimed epidemic of dependence. Concerns also exist for the significant increase in prescription of psychiatric drugs to children.[3][177]

Three authors have come to personify the movement against psychiatry, of which two are or have been practicing psychiatrists. The most influential was R.D. Laing, who wrote a series of best-selling books, including; The Divided Self. Thomas Szasz rose to fame with the book The Myth of Mental Illness. Michael Foucault challenged the very basis of psychiatric practice and cast it as repressive and controlling. The term "anti-psychiatry" itself was coined by David Cooper in 1967.[3][177]

Divergence within psychiatry generated the anti-psychiatry movement in the 1960s and 1970s, and is still present. Issues remaining relevant in contemporary psychiatry are questions of; freedom versus coercion, mind versus brain, nature versus nurture, and the right to be different.[3]

Psychiatric survivors movement

The psychiatric survivors movement[179] arose out of the civil rights ferment of the late 1960s and early 1970s and the personal histories of psychiatric abuse experienced by some ex-patients rather than the intradisciplinary discourse of antipsychiatry.[180] The key text in the intellectual development of the survivor movement, at least in the USA, was Judi Chamberlin's 1978 text, On Our Own: Patient Controlled Alternatives to the Mental Health System.[179][181] Chamberlin was an ex-patient and co-founder of the Mental Patients' Liberation Front.[182]

Coalescing around the ex-patient newsletter Dendron,[183] in late 1988 leaders from several of the main national and grassroots psychiatric survivor groups felt that an independent, human rights coalition focused on problems in the mental health system was needed. That year the Support Coalition International (SCI) was formed. SCI's first public action was to stage a counter-conference and protest in New York City, in May, 1990, at the same time as (and directly outside of) the American Psychiatric Association's annual meeting.[184] In 2005 the SCI changed its name to Mind Freedom International with David W. Oaks as its director.[180]