From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A gene is a segment of DNA that encodes function. A chromosome consists of a long strand of DNA containing many genes. A human chromosome can have up to 500 million base pairs of DNA with thousands of genes.

|

A gene is a locus (or region) of DNA that encodes a functional RNA or protein product, and is the molecular unit of heredity.[1][2]:Glossary The transmission of genes to an organism's offspring is the basis of the inheritance of phenotypic traits. Most biological traits are under the influence of polygenes (many different genes) as well as the gene–environment interactions. Some genetic traits are instantly visible, such as eye colour or number of limbs, and some are not, such as blood type, risk for specific diseases, or the thousands of basic biochemical processes that comprise life.

Genes can acquire mutations in their sequence, leading to different variants, known as alleles, in the population. These alleles encode slightly different versions of a protein, which cause different phenotype traits. Colloquial usage of the term "having a gene" (e.g., "good genes," "hair colour gene") typically refers to having a different allele of the gene. Genes evolve due to natural selection or survival of the fittest of the alleles.

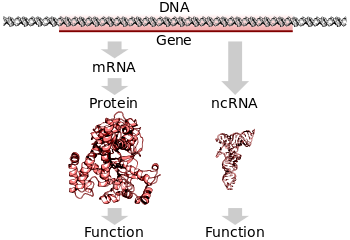

The concept of a gene continues to be refined as new phenomena are discovered.[3] For example, regulatory regions of a gene can be far removed from its coding regions, and coding regions can be split into several exons. Some viruses store their genome in RNA instead of DNA and some gene products are functional non-coding RNAs. Therefore, a broad, modern working definition of a gene is any discrete locus of heritable, genomic sequence which affect an organism's traits by being expressed as a functional product or by regulation of gene expression.[4][5]

History

Discovery of discrete inherited units

The existence of discrete inheritable units was first suggested by Gregor Mendel (1822–1884).[6] From 1857 to 1864, he studied inheritance patterns in 8000 common edible pea plants, tracking distinct traits from parent to offspring. He described these mathematically as 2n combinations where n is the number of differing characteristics in the original peas. Although he did not use the term gene, he explained his results in terms of discrete inherited units that give rise to observable physical characteristics. This description prefigured the distinction between genotype (the genetic material of an organism) and phenotype (the visible traits of that organism). Mendel was also the first to demonstrate independent assortment, the distinction between dominant and recessive traits, the distinction between a heterozygote and homozygote, and the phenomenon of discontinuous inheritance.Prior to Mendel's work, the dominant theory of heredity was one of blending inheritance, which suggested that each parent contributed fluids to the fertilisation process and that the traits of the parents blended and mixed to produce the offspring. Charles Darwin developed a theory of inheritance he termed pangenesis,[7] which used the term gemmule to describe hypothetical particles that would mix during reproduction. Although Mendel's work was largely unrecognized after its first publication in 1866, it was 'rediscovered' in 1900 by three European scientists, Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, and Erich von Tschermak, who claimed to have reached similar conclusions in their own research.[8]

The word gene is derived (via pangene) from the Ancient Greek word lγένος (génos) meaning "race, offspring".[9] Gene was coined in 1909 by Danish botanist Wilhelm Johannsen to describe the fundamental physical and functional unit of heredity,[10] while the related word genetics was first used by William Bateson in 1905.[11]

Discovery of DNA

Advances in understanding genes and inheritance continued throughout the 20th century. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was shown to be the molecular repository of genetic information by experiments in the 1940s to 1950s.[12][13] The structure of DNA was studied by Rosalind Franklin using X-ray crystallography, which led James D. Watson and Francis Crick to publish a model of the double-stranded DNA molecule whose paired nucleotide bases indicated a compelling hypothesis for the mechanism of genetic replication.[14][15] Collectively, this body of research established the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that proteins are translated from RNA, which is transcribed from DNA. This dogma has since been shown to have exceptions, such as reverse transcription in retroviruses. The modern study of genetics at the level of DNA is known as molecular genetics.In 1972, Walter Fiers and his team at the University of Ghent were the first to determine the sequence of a gene: the gene for Bacteriophage MS2 coat protein.[16] The subsequent development of chain-termination DNA sequencing in 1977 by Frederick Sanger improved the efficiency of sequencing and turned it into a routine laboratory tool.[17] An automated version of the Sanger method was used in early phases of the Human Genome Project.[18]

Modern evolutionary synthesis

The theories developed in the 1930s and 1940s to integrate molecular genetics with Darwinian evolution are called the modern evolutionary synthesis, a term introduced by Julian Huxley.[19]

Evolutionary biologists subsequently refined this concept, such as George C. Williams' gene-centric view of evolution. He proposed an evolutionary concept of the gene as a unit of natural selection with the definition: "that which segregates and recombines with appreciable frequency."[20]:24 In this view, the molecular gene transcribes as a unit, and the evolutionary gene inherits as a unit. Related ideas emphasizing the centrality of genes in evolution were popularized by Richard Dawkins.[21][22]

Two chains of DNA twist around each other to form a DNA double helix with the phosphate-sugar backbone spiralling around the outside, and the bases pointing inwards with adenine base pairing to thymine and guanine to cytosine. The specificity of base pairing occurs because adenine and thymine align form two hydrogen bonds, whereas cytosine and guanine form three hydrogen bonds. The two strands in a double helix must therefore be complementary, with their sequence of bases matching such that the adenines of one strand are paired with the thymines of the other strand, and so on.[2]:4.1

Due to the chemical composition of the pentose residues of the bases, DNA strands have directionality. One end of a DNA polymer contains an exposed hydroxyl group on the deoxyribose; this is known as the 3' end of the molecule. The other end contains an exposed phosphate group; this is the 5' end. The two strands of a double-helix run in opposite directions. Nucleic acid synthesis, including DNA replication and transcription occurs in the 5'→3' direction, because new nucleotides are added via a dehydration reaction that uses the exposed 3' hydroxyl as a nucleophile.[23]:27.2

The expression of genes encoded in DNA begins by transcribing the gene into RNA, a second type of nucleic acid that is very similar to DNA, but whose monomers contain the sugar ribose rather than deoxyribose. RNA also contains the base uracil in place of thymine. RNA molecules are less stable than DNA and are typically single-stranded. Genes that encode proteins are composed of a series of three-nucleotide sequences called codons, which serve as the "words" in the genetic "language". The genetic code specifies the correspondence during protein translation between codons and amino acids. The genetic code is nearly the same for all known organisms.[2]:4.1

The total complement of genes in an organism or cell is known as its genome, which may be stored on one or more chromosomes. A chromosome consists of a single, very long DNA helix on which thousands of genes are encoded.[2]:4.2 The region of the chromosome at which a particular gene is located is called its locus. Each locus contains one allele of a gene; however, members of a population may have different alleles at the locus, each with a slightly different gene sequence.

The majority of eukaryotic genes are stored on a set of large, linear chromosomes. The chromosomes are packed within the nucleus in complex with storage proteins called histones to form a unit called a nucleosome. DNA packaged and condensed in this way is called chromatin.[2]:4.2 The manner in which DNA is stored on the histones, as well as chemical modifications of the histone itself, regulate whether a particular region of DNA is accessible for gene expression. In addition to genes, eukaryotic chromosomes contain sequences involved in ensuring that the DNA is copied without degradation of end regions and sorted into daughter cells during cell division: replication origins, telomeres and the centromere.[2]:4.2 Replication origins are the sequence regions where DNA replication is initiated to make two copies of the chromosome. Telomeres are long stretches of repetitive sequence that cap the ends of the linear chromosomes and prevent degradation of coding and regulatory regions during DNA replication. The length of the telomeres decreases each time the genome is replicated and has been implicated in the aging process.[25] The centromere is required for binding spindle fibres to separate sister chromatids into daughter cells during cell division.[2]:18.2

Prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) typically store their genomes on a single large, circular chromosome. Similarly, some eukaryotic organelles contain a remnant circular chromosome with a small number of genes.[2]:14.4 Prokaryotes sometimes supplement their chromosome with additional small circles of DNA called plasmids, which usually encode only a few genes and are transferable between individuals. For example, the genes for antibiotic resistance are usually encoded on bacterial plasmids and can be passed between individual cells, even those of different species, via horizontal gene transfer.[26]

Whereas the chromosomes of prokaryotes are relatively gene-dense, those of eukaryotes often contain regions of DNA that serve no obvious function. Simple single-celled eukaryotes have relatively small amounts of such DNA, whereas the genomes of complex multicellular organisms, including humans, contain an absolute majority of DNA without an identified function.[27] This DNA has often been referred to as "junk DNA". However, more recent analyses suggest that, although protein-coding DNA makes up barely 2% of the human genome, about 80% of the bases in the genome may be expressed, so the term "junk DNA" may be a misnomer.[5]

The Thestructure of a gene consists of many elements of which the actual protein coding sequence is often only a small part. These include DNA regions that are not transcribed as well as untranslated regions of the RNA.

Firstly, flanking the open reading frame, all genes contain a regulatory sequence that is required for their expression. In order to be expressed, genes require a promoter sequence. The promoter is recognized and bound by transcription factors and RNA polymerase to initiate transcription.[2]:7.1 A gene can have more than one promoter, resulting in mRNAs that differ in how far they extend in the 5' end.[28] Promoter regions have a consensus sequence, however highly transcribed genes have "strong" promoter sequences that bind the transcription machinery well, whereas others have "weak" promoters that bind poorly and initiate transcription less frequently.[2]:7.2 Eukaryotic promoter regions are much more complex and difficult to identify than prokaryotic promoters.[2]:7.3

Additionally, genes can have regulatory regions many kilobases upstream or downstream of the open reading frame. These act by binding to transcription factors which then cause the DNA to loop so that the regulatory sequence (and bound transcription factor) become close to the RNA polymerase binding site.[29] For example, enhancers increase transcription by binding an activator protein which then helps to recruit the RNA polymerase to the promoter; conversely silencers bind repressor proteins and make the DNA less available for RNA polymerase.[30]

The transcribed pre-mRNA contains untranslated regions at both ends which contain a ribosome binding site, terminator and start and stop codons.[31] In addition, most eukaryotic open reading frames contain untranslated introns which are removed before the exons are translated. The sequences at the ends of the introns, dictate the splice sites to generate the final mature mRNA which encodes the protein or RNA product.[32]

Many prokaryotic genes are organized into operons, with multiple protein-coding sequences that are transcribed as a unit.[33][34] The products of operon genes typically have related functions and are involved in the same regulatory network.[2]:7.3

Early work in molecular genetics suggested the model that one gene makes one protein. This model has been refined since the discovery of genes that can encode multiple proteins by alternative splicing and coding sequences split in short section across the genome whose mRNAs are concatenated by trans-splicing.[5][37][38]

A broad operational definition is sometimes used to encompass the complexity of these diverse phenomena, where a gene is defined as a union of genomic sequences encoding a coherent set of potentially overlapping functional products.[11] This definition categorizes genes by their functional products (proteins or RNA) rather than their specific DNA loci, with regulatory elements classified as gene-associated regions.[11]

The nucleotide sequence of a gene's DNA specifies the amino acid sequence of a protein through the genetic code. Sets of three nucleotides, known as codons, each correspond to a specific amino acid.[2]:6 Additionally, a "start codon", and three "stop codons" indicate the beginning and end of the protein coding region. There are 64 possible codons (four possible nucleotides at each of three positions, hence 43 possible codons) and only 20 standard amino acids; hence the code is redundant and multiple codons can specify the same amino acid. The correspondence between codons and amino acids is nearly universal among all known living organisms.[40]

In prokaryotes, transcription occurs in the cytoplasm; for very long transcripts, translation may begin at the 5' end of the RNA while the 3' end is still being transcribed. In eukaryotes, transcription occurs in the nucleus, where the cell's DNA is stored. The RNA molecule produced by the polymerase is known as the primary transcript and undergoes post-transcriptional modifications before being exported to the cytoplasm for translation. One of the modifications performed is the splicing of introns which are sequences in the transcribed region that do not encode protein. Alternative splicing mechanisms can result in mature transcripts from the same gene having different sequences and thus coding for different proteins. This is a major form of regulation in eukaryotic cells and also occurs in some prokaryotes.[2]:7.5[41]

Translation is the process by which a mature mRNA molecule is used as a template for synthesizing a new protein.[2]:6.2 Translation is carried out by ribosomes, large complexes of RNA and protein responsible for carrying out the chemical reactions to add new amino acids to a growing polypeptide chain by the formation of peptide bonds. The genetic code is read three nucleotides at a time, in units called codons, via interactions with specialized RNA molecules called transfer RNA (tRNA). Each tRNA has three unpaired bases known as the anticodon that are complementary to the codon it reads on the mRNA. The tRNA is also covalently attached to the amino acid specified by the complementary codon. When the tRNA binds to its complementary codon in an mRNA strand, the ribosome attaches its amino acid cargo to the new polypeptide chain, which is synthesized from amino terminus to carboxyl terminus. During and after synthesis, most new proteins must folds to their active three-dimensional structure before they can carry out their cellular functions.[2]:3

Some viruses store their entire genomes in the form of RNA, and contain no DNA at all.[43][44] Because they use RNA to store genes, their cellular hosts may synthesize their proteins as soon as they are infected and without the delay in waiting for transcription.[45] On the other hand, RNA retroviruses, such as HIV, require the reverse transcription of their genome from RNA into DNA before their proteins can be synthesized. RNA-mediated epigenetic inheritance has also been observed in plants and very rarely in animals.[46]

Organisms inherit their genes from their parents. Asexual organisms simply inherit a complete copy of their parent's genome. Sexual organisms have two copies of each chromosome because they inherit one complete set from each parent.[2]:1

Alleles at a locus may be dominant or recessive; dominant alleles give rise to their corresponding phenotypes when paired with any other allele for the same trait, whereas recessive alleles give rise to their corresponding phenotype only when paired with another copy of the same allele. For example, if the allele specifying tall stems in pea plants is dominant over the allele specifying short stems, then pea plants that inherit one tall allele from one parent and one short allele from the other parent will also have tall stems. Mendel's work demonstrated that alleles assort independently in the production of gametes, or germ cells, ensuring variation in the next generation. Although Mendelian inheritance remains a good model for many traits determined by single genes (including a number of well-known genetic disorders) it does not include the physical processes of DNA replication and cell division.[47][48]

After DNA replication is complete, the cell must physically separate the two copies of the genome and divide into two distinct membrane-bound cells.[2]:18.2 In prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) this usually occurs via a relatively simple process called binary fission, in which each circular genome attaches to the cell membrane and is separated into the daughter cells as the membrane invaginates to split the cytoplasm into two membrane-bound portions. Binary fission is extremely fast compared to the rates of cell division in eukaryotes. Eukaryotic cell division is a more complex process known as the cell cycle; DNA replication occurs during a phase of this cycle known as S phase, whereas the process of segregating chromosomes and splitting the cytoplasm occurs during M phase.[2]:18.1

During the process of meiotic cell division, an event called genetic recombination or crossing-over can sometimes occur, in which a length of DNA on one chromatid is swapped with a length of DNA on the corresponding sister chromatid. This has no effect if the alleles on the chromatids are the same, but results in reassortment of otherwise linked alleles if they are different.[2]:5.5 The Mendelian principle of independent assortment asserts that each of a parent's two genes for each trait will sort independently into gametes; which allele an organism inherits for one trait is unrelated to which allele it inherits for another trait. This is in fact only true for genes that do not reside on the same chromosome, or are located very far from one another on the same chromosome. The closer two genes lie on the same chromosome, the more closely they will be associated in gametes and the more often they will appear together; genes that are very close are essentially never separated because it is extremely unlikely that a crossover point will occur between them. This is known as genetic linkage.[49]

Molecular evolution

When multiple different alleles for a gene are present in a species's population it is called polymorphic. Most different alleles are functionally equivalent, however some alleles can give rise to different phenotypic traits. A gene's most common allele is called the wild type, and rare alleles are called mutants. The genetic variation in relative frequencies of different alleles in a population is due to both natural selection and genetic drift.[54] The wild-type allele is not necessarily the ancestor of less common alleles, nor is it necessarily fitter.

Most mutations within genes are neutral, having no effect on the organism's phenotype (silent mutations). Some mutations do not change the amino acid sequence because multiple codons encode the same amino acid (synonymous mutations). Other mutations can be neutral if they lead to amino acid sequence changes, but the protein still functions similarly with the new amino acid (e.g. conservative mutations). Many mutations, however, are deleterious or even lethal, and are removed from populations by natural selection. Genetic disorders are the result of deleterious mutations and can be due to spontaneous mutation in the affected individual, or can be inherited. Finally, a small fraction of mutations are beneficial, improving the organism's fitness and are extremely important for evolution, since their directional selection leads to adaptive evolution.[2]:7.6

Genes with a most recent common ancestor, and thus a shared evolutionary ancestry, are known as homologs.[55] These genes appear either from gene duplication within an organism's genome, where they are known as paralogous genes, or are the result of divergence of the genes after a speciation event, where they are known as orthologous genes,[2]:7.6 and often perform the same or similar functions in related organisms. It is often assumed that the functions of orthologous genes are more similar than those of paralogous genes, although the difference is minimal.[56][57]

The relationship between genes can be measured by comparing the sequence alignment of their DNA.[2]:7.6 The degree of sequence similarity between homologous genes is called conserved sequence. Most changes to a gene's sequence do not affect its function and so genes accumulate mutations over time by neutral molecular evolution. Additionally, any selection on a gene will cause its sequence to diverge at a different rate. Genes under stabilizing selection are constrained and so change more slowly whereas genes under directional selection change sequence more rapidly.[58] The sequence differences between genes can be used for phylogenetic analyses to study how those genes have evolved and how the organisms they come from are related.[59][60]

Origins of new genes

The most common source of new genes in eukaryotic lineages is gene duplication, which creates copy number variation of an existing gene in the genome.[61][62] The resulting genes (paralogs) may then diverge in sequence and in function. Sets of genes formed in this way comprise a gene family. Gene duplications and losses within a family are common and represent a major source of evolutionary biodiversity.[63] Sometimes, gene duplication may result in a nonfunctional copy of a gene, or a functional copy may be subject to mutations that result in loss of function; such nonfunctional genes are called pseudogenes.[2]:7.6

De novo or "orphan" genes, whose sequence shows no similarity to existing genes, are extremely rare. Estimates of the number of de novo genes in the human genome range from 18[64] to 60.[65] Such genes are typically shorter and simpler in structure than most eukaryotic genes, with few if any introns.[61] Two primary sources of orphan protein-coding genes are gene duplication followed by extremely rapid sequence change, such that the original relationship is undetectable by sequence comparisons, and formation through mutation of "cryptic" transcription start sites that introduce a new open reading frame in a region of the genome that did not previously code for a protein.[66][67]

Horizontal gene transfer refers to the transfer of genetic material through a mechanism other than reproduction. This mechanism is a common source of new genes in prokaryotes, sometimes thought to contribute more to genetic variation than gene duplication.[68] It is a common means of spreading antibiotic resistance, virulence, and adaptive metabolic functions.[26][69] Although horizontal gene transfer is rare in eukaryotes, likely examples have been identified of protist and alga genomes containing genes of bacterial origin.[70][71]

Genome

The genome is the total genetic material of an organism and includes both the genes and non-coding sequences.[72]

Number of genes

The genome size, and the number of genes it encodes varies widely between organisms. The smallest genomes occur in viruses (which can have as few as 2 protein-coding genes),[81] and viroids (which act as a single non-coding RNA gene).[82] Conversely, plants can have extremely large genomes,[83] with rice containing >46,000 protein-coding genes.[84] The total number of protein-coding genes (the Earth's proteome) is estimated to be 5 million sequences.[85]

Although the number of base-pairs of DNA in the human genome has been known since the 1960s, the estimated number of genes has changed over time as definitions of genes, and methods of detecting them have been refined. Initial theoretical predictions of the number of human genes were as high as 2,000,000.[86] Early experimental measures indicated there to be 50,000–100,000 transcribed genes (expressed sequence tags).[87] Subsequently, the sequencing in the Human Genome Project indicated that many of these transcripts were alternative variants of the same genes, and the total number of protein-coding genes was revised down to ~20,000[80] with 13 genes encoded on the mitochondrial genome.[78] Of the human genome, only 1–2% consists of protein-coding genes,[88] with the remainder being 'noncoding' DNA such as introns, retrotransposons, and noncoding RNAs.[88][89]

Essential genes

Essential genes are the set of genes thought to be critical for an organism's survival.[90] This definition assumes the abundant availability of all relevant nutrients and the absence of environmental stress. Only a small portion of an organism's genes are essential. In bacteria, an estimated 250–400 genes are essential for Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, which is less than 10% of their genes.[91][92][93] Half of these genes are orthologs in both organisms and are largely involved in protein synthesis.[93] In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae the number of essential genes is slightly higher, at 1000 genes (~20% of their genes).[94] Although the number is more difficult to measure in higher eukaryotes, mice and humans are estimated to have around 2000 essential genes (~10% of their genes).[95]

Housekeeping genes are critical for carrying out basic cell functions and so are expressed at a relatively constant level (constitutively).[96] Since their expression is constant, housekeeping genes are used as experimental controls when analysing gene expression. Not all essential genes are housekeeping genes since some essential genes are developmentally regulated or expressed at certain times during the organism's life cycle.[97]

Genetic and genomic nomenclature

Gene nomenclature has been established by the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) for each known human gene in the form of an approved gene name and symbol (short-form abbreviation), which can be accessed through a database maintained by HGNC. Symbols are chosen to be unique, and each gene has only one symbol (although approved symbols sometimes change). Symbols are preferably kept consistent with other members of a gene family and with homologs in other species, particularly the mouse due to its role as a common model organism.[98]

Genetic engineering

Molecular basis

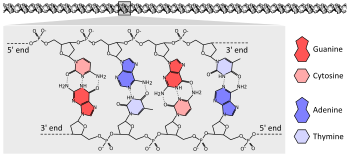

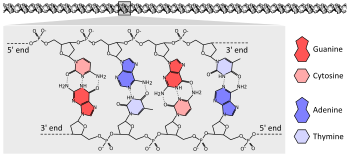

The chemical structure of a four base pair fragment of a DNA double helix. The sugar-phosphate backbone chains run in opposite directions with the bases pointing inwards, base-pairing A to T and C to G with hydrogen bonds.

DNA

The vast majority of living organisms encode their genes in long strands of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). DNA consists of a chain made from four types of nucleotide subunits, each composed of: a five-carbon sugar (2'-deoxyribose), a phosphate group, and one of the four bases adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine.[2]:2.1Two chains of DNA twist around each other to form a DNA double helix with the phosphate-sugar backbone spiralling around the outside, and the bases pointing inwards with adenine base pairing to thymine and guanine to cytosine. The specificity of base pairing occurs because adenine and thymine align form two hydrogen bonds, whereas cytosine and guanine form three hydrogen bonds. The two strands in a double helix must therefore be complementary, with their sequence of bases matching such that the adenines of one strand are paired with the thymines of the other strand, and so on.[2]:4.1

Due to the chemical composition of the pentose residues of the bases, DNA strands have directionality. One end of a DNA polymer contains an exposed hydroxyl group on the deoxyribose; this is known as the 3' end of the molecule. The other end contains an exposed phosphate group; this is the 5' end. The two strands of a double-helix run in opposite directions. Nucleic acid synthesis, including DNA replication and transcription occurs in the 5'→3' direction, because new nucleotides are added via a dehydration reaction that uses the exposed 3' hydroxyl as a nucleophile.[23]:27.2

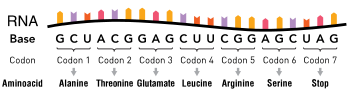

The expression of genes encoded in DNA begins by transcribing the gene into RNA, a second type of nucleic acid that is very similar to DNA, but whose monomers contain the sugar ribose rather than deoxyribose. RNA also contains the base uracil in place of thymine. RNA molecules are less stable than DNA and are typically single-stranded. Genes that encode proteins are composed of a series of three-nucleotide sequences called codons, which serve as the "words" in the genetic "language". The genetic code specifies the correspondence during protein translation between codons and amino acids. The genetic code is nearly the same for all known organisms.[2]:4.1

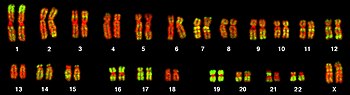

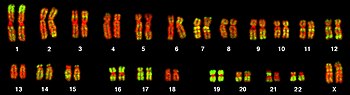

Chromosomes

Fluorescent microscopy image of a human female karyotype, showing 23 pairs of chromosomes . The DNA is stained red, with regions rich in housekeeping genes further stained in green. The largest chromosomes are around 10 times the size of the smallest.[24]

The total complement of genes in an organism or cell is known as its genome, which may be stored on one or more chromosomes. A chromosome consists of a single, very long DNA helix on which thousands of genes are encoded.[2]:4.2 The region of the chromosome at which a particular gene is located is called its locus. Each locus contains one allele of a gene; however, members of a population may have different alleles at the locus, each with a slightly different gene sequence.

The majority of eukaryotic genes are stored on a set of large, linear chromosomes. The chromosomes are packed within the nucleus in complex with storage proteins called histones to form a unit called a nucleosome. DNA packaged and condensed in this way is called chromatin.[2]:4.2 The manner in which DNA is stored on the histones, as well as chemical modifications of the histone itself, regulate whether a particular region of DNA is accessible for gene expression. In addition to genes, eukaryotic chromosomes contain sequences involved in ensuring that the DNA is copied without degradation of end regions and sorted into daughter cells during cell division: replication origins, telomeres and the centromere.[2]:4.2 Replication origins are the sequence regions where DNA replication is initiated to make two copies of the chromosome. Telomeres are long stretches of repetitive sequence that cap the ends of the linear chromosomes and prevent degradation of coding and regulatory regions during DNA replication. The length of the telomeres decreases each time the genome is replicated and has been implicated in the aging process.[25] The centromere is required for binding spindle fibres to separate sister chromatids into daughter cells during cell division.[2]:18.2

Prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) typically store their genomes on a single large, circular chromosome. Similarly, some eukaryotic organelles contain a remnant circular chromosome with a small number of genes.[2]:14.4 Prokaryotes sometimes supplement their chromosome with additional small circles of DNA called plasmids, which usually encode only a few genes and are transferable between individuals. For example, the genes for antibiotic resistance are usually encoded on bacterial plasmids and can be passed between individual cells, even those of different species, via horizontal gene transfer.[26]

Whereas the chromosomes of prokaryotes are relatively gene-dense, those of eukaryotes often contain regions of DNA that serve no obvious function. Simple single-celled eukaryotes have relatively small amounts of such DNA, whereas the genomes of complex multicellular organisms, including humans, contain an absolute majority of DNA without an identified function.[27] This DNA has often been referred to as "junk DNA". However, more recent analyses suggest that, although protein-coding DNA makes up barely 2% of the human genome, about 80% of the bases in the genome may be expressed, so the term "junk DNA" may be a misnomer.[5]

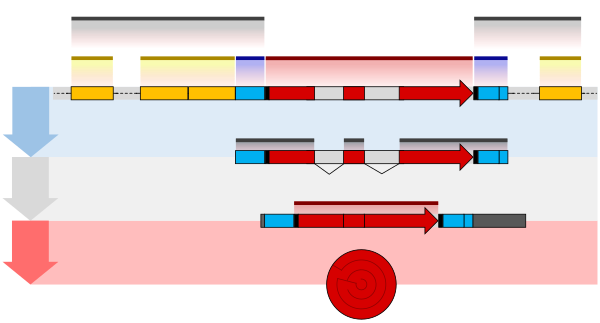

Structure and function

The structure of a eukaryotic protein-coding gene. Regulatory sequence controls when and where expression occurs for the protein coding region (red). Promoter and enhancer regions (yellow) regulate the transcription of the gene into a pre-mRNA which is modified to add a 5' cap and poly-A tail (grey) and remove introns. The mRNA 5' and 3' untranslated regions (blue) regulate translation into the final protein product.

The structure of a prokaryotic operon of protein-coding genes. Regulatory sequence controls when expression occurs for the multiple protein coding regions (red). Promoter, operator and enhancer regions (yellow) regulate the transcription of the gene into an mRNA. The mRNA untranslated regions (blue) regulate translation into the final protein products.

|

Firstly, flanking the open reading frame, all genes contain a regulatory sequence that is required for their expression. In order to be expressed, genes require a promoter sequence. The promoter is recognized and bound by transcription factors and RNA polymerase to initiate transcription.[2]:7.1 A gene can have more than one promoter, resulting in mRNAs that differ in how far they extend in the 5' end.[28] Promoter regions have a consensus sequence, however highly transcribed genes have "strong" promoter sequences that bind the transcription machinery well, whereas others have "weak" promoters that bind poorly and initiate transcription less frequently.[2]:7.2 Eukaryotic promoter regions are much more complex and difficult to identify than prokaryotic promoters.[2]:7.3

Additionally, genes can have regulatory regions many kilobases upstream or downstream of the open reading frame. These act by binding to transcription factors which then cause the DNA to loop so that the regulatory sequence (and bound transcription factor) become close to the RNA polymerase binding site.[29] For example, enhancers increase transcription by binding an activator protein which then helps to recruit the RNA polymerase to the promoter; conversely silencers bind repressor proteins and make the DNA less available for RNA polymerase.[30]

The transcribed pre-mRNA contains untranslated regions at both ends which contain a ribosome binding site, terminator and start and stop codons.[31] In addition, most eukaryotic open reading frames contain untranslated introns which are removed before the exons are translated. The sequences at the ends of the introns, dictate the splice sites to generate the final mature mRNA which encodes the protein or RNA product.[32]

Many prokaryotic genes are organized into operons, with multiple protein-coding sequences that are transcribed as a unit.[33][34] The products of operon genes typically have related functions and are involved in the same regulatory network.[2]:7.3

Functional definitions

Defining exactly what section of a DNA sequence comprises a gene is difficult.[3] Regulatory regions of a gene such as enhancers do not necessarily have to be close to the coding sequence on the linear molecule because the intervening DNA can be looped out to bring the gene and its regulatory region into proximity. Similarly, a gene's introns can be much larger than its exons. Regulatory regions can even be on entirely different chromosomes and operate in trans to allow regulatory regions on one chromosome to come in contact with target genes on another chromosome.[35][36]Early work in molecular genetics suggested the model that one gene makes one protein. This model has been refined since the discovery of genes that can encode multiple proteins by alternative splicing and coding sequences split in short section across the genome whose mRNAs are concatenated by trans-splicing.[5][37][38]

A broad operational definition is sometimes used to encompass the complexity of these diverse phenomena, where a gene is defined as a union of genomic sequences encoding a coherent set of potentially overlapping functional products.[11] This definition categorizes genes by their functional products (proteins or RNA) rather than their specific DNA loci, with regulatory elements classified as gene-associated regions.[11]

Gene expression

In all organisms, two steps are required to read the information encoded in a gene's DNA and produce the protein it specifies. First, the gene's DNA is transcribed to messenger RNA (mRNA).[2]:6.1 Second, that mRNA is translated to protein.[2]:6.2 RNA-coding genes must still go through the first step, but are not translated into protein.[39] The process of producing a biologically functional molecule of either RNA or protein is called gene expression, and the resulting molecule is called a gene product.Genetic code

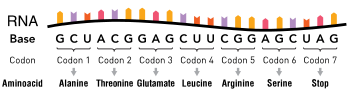

Schematic of a single-stranded RNA molecule illustrating a series of three-base codons. Each three-nucleotide codon corresponds to an amino acid when translated to protein

The nucleotide sequence of a gene's DNA specifies the amino acid sequence of a protein through the genetic code. Sets of three nucleotides, known as codons, each correspond to a specific amino acid.[2]:6 Additionally, a "start codon", and three "stop codons" indicate the beginning and end of the protein coding region. There are 64 possible codons (four possible nucleotides at each of three positions, hence 43 possible codons) and only 20 standard amino acids; hence the code is redundant and multiple codons can specify the same amino acid. The correspondence between codons and amino acids is nearly universal among all known living organisms.[40]

Transcription

Transcription produces a single-stranded RNA molecule known as messenger RNA, whose nucleotide sequence is complementary to the DNA from which it was transcribed.[2]:6.1 The mRNA acts as an intermediate between the DNA gene and its final protein product. The gene's DNA is used as a template to generate a complementary mRNA. The mRNA matches the sequence of the gene's DNA coding strand because it is synthesised as the complement of the template strand. Transcription is performed by an enzyme called an RNA polymerase, which reads the template strand in the 3' to 5' direction and synthesizes the RNA from 5' to 3'. To initiate transcription, the polymerase first recognizes and binds a promoter region of the gene. Thus, a major mechanism of gene regulation is the blocking or sequestering the promoter region, either by tight binding by repressor molecules that physically block the polymerase, or by organizing the DNA so that the promoter region is not accessible.[2]:7In prokaryotes, transcription occurs in the cytoplasm; for very long transcripts, translation may begin at the 5' end of the RNA while the 3' end is still being transcribed. In eukaryotes, transcription occurs in the nucleus, where the cell's DNA is stored. The RNA molecule produced by the polymerase is known as the primary transcript and undergoes post-transcriptional modifications before being exported to the cytoplasm for translation. One of the modifications performed is the splicing of introns which are sequences in the transcribed region that do not encode protein. Alternative splicing mechanisms can result in mature transcripts from the same gene having different sequences and thus coding for different proteins. This is a major form of regulation in eukaryotic cells and also occurs in some prokaryotes.[2]:7.5[41]

Translation

Translation is the process by which a mature mRNA molecule is used as a template for synthesizing a new protein.[2]:6.2 Translation is carried out by ribosomes, large complexes of RNA and protein responsible for carrying out the chemical reactions to add new amino acids to a growing polypeptide chain by the formation of peptide bonds. The genetic code is read three nucleotides at a time, in units called codons, via interactions with specialized RNA molecules called transfer RNA (tRNA). Each tRNA has three unpaired bases known as the anticodon that are complementary to the codon it reads on the mRNA. The tRNA is also covalently attached to the amino acid specified by the complementary codon. When the tRNA binds to its complementary codon in an mRNA strand, the ribosome attaches its amino acid cargo to the new polypeptide chain, which is synthesized from amino terminus to carboxyl terminus. During and after synthesis, most new proteins must folds to their active three-dimensional structure before they can carry out their cellular functions.[2]:3

Regulation

Genes are regulated so that they are expressed only when the product is needed, since expression draws on limited resources.[2]:7 A cell regulates its gene expression depending on its external environment (e.g. available nutrients, temperature and other stresses), its internal environment (e.g. cell division cycle, metabolism, infection status), and its specific role if in a multicellular organism. Gene expression can be regulated at any step: from transcriptional initiation, to RNA processing, to post-translational modification of the protein. The regulation of lactose metabolism genes in E. coli (lac operon) was the first such mechanism to be described in 1961.[42]RNA genes

A typical protein-coding gene is first copied into RNA as an intermediate in the manufacture of the final protein product.[2]:6.1 In other cases, the RNA molecules are the actual functional products, as in the synthesis of ribosomal RNA and transfer RNA. Some RNAs known as ribozymes are capable of enzymatic function, and microRNA has a regulatory role. The DNA sequences from which such RNAs are transcribed are known as non-coding RNA genes.[39]Some viruses store their entire genomes in the form of RNA, and contain no DNA at all.[43][44] Because they use RNA to store genes, their cellular hosts may synthesize their proteins as soon as they are infected and without the delay in waiting for transcription.[45] On the other hand, RNA retroviruses, such as HIV, require the reverse transcription of their genome from RNA into DNA before their proteins can be synthesized. RNA-mediated epigenetic inheritance has also been observed in plants and very rarely in animals.[46]

Inheritance

Inheritance of a gene that has two different alleles (blue and white). The gene is located on an autosomal chromosome. The blue allele is recessive to the white allele. The probability of each outcome in the children's generation is one quarter, or 25 percent.

Organisms inherit their genes from their parents. Asexual organisms simply inherit a complete copy of their parent's genome. Sexual organisms have two copies of each chromosome because they inherit one complete set from each parent.[2]:1

Mendelian inheritance

According to Mendelian inheritance, variations in an organism's phenotype (observable physical and behavioral characteristics) are due in part to variations in its genotype (particular set of genes). Each gene specifies a particular trait with different sequence of a gene (alleles) giving rise to different phenotypes. Most eukaryotic organisms (such as the pea plants Mendel worked on) have two alleles for each trait, one inherited from each parent.[2]:20Alleles at a locus may be dominant or recessive; dominant alleles give rise to their corresponding phenotypes when paired with any other allele for the same trait, whereas recessive alleles give rise to their corresponding phenotype only when paired with another copy of the same allele. For example, if the allele specifying tall stems in pea plants is dominant over the allele specifying short stems, then pea plants that inherit one tall allele from one parent and one short allele from the other parent will also have tall stems. Mendel's work demonstrated that alleles assort independently in the production of gametes, or germ cells, ensuring variation in the next generation. Although Mendelian inheritance remains a good model for many traits determined by single genes (including a number of well-known genetic disorders) it does not include the physical processes of DNA replication and cell division.[47][48]

DNA replication and cell division

The growth, development, and reproduction of organisms relies on cell division, or the process by which a single cell divides into two usually identical daughter cells. This requires first making a duplicate copy of every gene in the genome in a process called DNA replication.[2]:5.2 The copies are made by specialized enzymes known as DNA polymerases, which "read" one strand of the double-helical DNA, known as the template strand, and synthesize a new complementary strand. Because the DNA double helix is held together by base pairing, the sequence of one strand completely specifies the sequence of its complement; hence only one strand needs to be read by the enzyme to produce a faithful copy. The process of DNA replication is semiconservative; that is, the copy of the genome inherited by each daughter cell contains one original and one newly synthesized strand of DNA.[2]:5.2After DNA replication is complete, the cell must physically separate the two copies of the genome and divide into two distinct membrane-bound cells.[2]:18.2 In prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) this usually occurs via a relatively simple process called binary fission, in which each circular genome attaches to the cell membrane and is separated into the daughter cells as the membrane invaginates to split the cytoplasm into two membrane-bound portions. Binary fission is extremely fast compared to the rates of cell division in eukaryotes. Eukaryotic cell division is a more complex process known as the cell cycle; DNA replication occurs during a phase of this cycle known as S phase, whereas the process of segregating chromosomes and splitting the cytoplasm occurs during M phase.[2]:18.1

Molecular inheritance

The duplication and transmission of genetic material from one generation of cells to the next is the basis for molecular inheritance, and the link between the classical and molecular pictures of genes. Organisms inherit the characteristics of their parents because the cells of the offspring contain copies of the genes in their parents' cells. In asexually reproducing organisms, the offspring will be a genetic copy or clone of the parent organism. In sexually reproducing organisms, a specialized form of cell division called meiosis produces cells called gametes or germ cells that are haploid, or contain only one copy of each gene.[2]:20.2 The gametes produced by females are called eggs or ova, and those produced by males are called sperm. Two gametes fuse to form a diploid fertilized egg, a single cell that has two sets of genes, with one copy of each gene from the mother and one from the father.[2]:20During the process of meiotic cell division, an event called genetic recombination or crossing-over can sometimes occur, in which a length of DNA on one chromatid is swapped with a length of DNA on the corresponding sister chromatid. This has no effect if the alleles on the chromatids are the same, but results in reassortment of otherwise linked alleles if they are different.[2]:5.5 The Mendelian principle of independent assortment asserts that each of a parent's two genes for each trait will sort independently into gametes; which allele an organism inherits for one trait is unrelated to which allele it inherits for another trait. This is in fact only true for genes that do not reside on the same chromosome, or are located very far from one another on the same chromosome. The closer two genes lie on the same chromosome, the more closely they will be associated in gametes and the more often they will appear together; genes that are very close are essentially never separated because it is extremely unlikely that a crossover point will occur between them. This is known as genetic linkage.[49]

Molecular evolution

Mutation

DNA replication is for the most part extremely accurate, however errors (mutations) do occur.[2]:7.6 The error rate in eukaryotic cells can be as low as 10−8 per nucleotide per replication,[50][51] whereas for some RNA viruses it can be as high as 10−3.[52] This means that each generation, each human genome accumulates 1–2 new mutations.[52] Small mutations can be caused by DNA replication and the aftermath of DNA damage and include point mutations in which a single base is altered and frameshift mutations in which a single base is inserted or deleted. Either of these mutations can change the gene by missense (change a codon to encode a different amino acid) or nonsense (a premature stop codon).[53] Larger mutations can be caused by errors in recombination to cause chromosomal abnormalities including the duplication, deletion, rearrangement or inversion of large sections of a chromosome. Additionally, the DNA repair mechanisms that normally revert mutations can introduce errors when repairing the physical damage to the molecule is more important than restoring an exact copy, for example when repairing double-strand breaks.[2]:5.4When multiple different alleles for a gene are present in a species's population it is called polymorphic. Most different alleles are functionally equivalent, however some alleles can give rise to different phenotypic traits. A gene's most common allele is called the wild type, and rare alleles are called mutants. The genetic variation in relative frequencies of different alleles in a population is due to both natural selection and genetic drift.[54] The wild-type allele is not necessarily the ancestor of less common alleles, nor is it necessarily fitter.

Most mutations within genes are neutral, having no effect on the organism's phenotype (silent mutations). Some mutations do not change the amino acid sequence because multiple codons encode the same amino acid (synonymous mutations). Other mutations can be neutral if they lead to amino acid sequence changes, but the protein still functions similarly with the new amino acid (e.g. conservative mutations). Many mutations, however, are deleterious or even lethal, and are removed from populations by natural selection. Genetic disorders are the result of deleterious mutations and can be due to spontaneous mutation in the affected individual, or can be inherited. Finally, a small fraction of mutations are beneficial, improving the organism's fitness and are extremely important for evolution, since their directional selection leads to adaptive evolution.[2]:7.6

Sequence homology

Genes with a most recent common ancestor, and thus a shared evolutionary ancestry, are known as homologs.[55] These genes appear either from gene duplication within an organism's genome, where they are known as paralogous genes, or are the result of divergence of the genes after a speciation event, where they are known as orthologous genes,[2]:7.6 and often perform the same or similar functions in related organisms. It is often assumed that the functions of orthologous genes are more similar than those of paralogous genes, although the difference is minimal.[56][57]

The relationship between genes can be measured by comparing the sequence alignment of their DNA.[2]:7.6 The degree of sequence similarity between homologous genes is called conserved sequence. Most changes to a gene's sequence do not affect its function and so genes accumulate mutations over time by neutral molecular evolution. Additionally, any selection on a gene will cause its sequence to diverge at a different rate. Genes under stabilizing selection are constrained and so change more slowly whereas genes under directional selection change sequence more rapidly.[58] The sequence differences between genes can be used for phylogenetic analyses to study how those genes have evolved and how the organisms they come from are related.[59][60]

Origins of new genes

The most common source of new genes in eukaryotic lineages is gene duplication, which creates copy number variation of an existing gene in the genome.[61][62] The resulting genes (paralogs) may then diverge in sequence and in function. Sets of genes formed in this way comprise a gene family. Gene duplications and losses within a family are common and represent a major source of evolutionary biodiversity.[63] Sometimes, gene duplication may result in a nonfunctional copy of a gene, or a functional copy may be subject to mutations that result in loss of function; such nonfunctional genes are called pseudogenes.[2]:7.6

De novo or "orphan" genes, whose sequence shows no similarity to existing genes, are extremely rare. Estimates of the number of de novo genes in the human genome range from 18[64] to 60.[65] Such genes are typically shorter and simpler in structure than most eukaryotic genes, with few if any introns.[61] Two primary sources of orphan protein-coding genes are gene duplication followed by extremely rapid sequence change, such that the original relationship is undetectable by sequence comparisons, and formation through mutation of "cryptic" transcription start sites that introduce a new open reading frame in a region of the genome that did not previously code for a protein.[66][67]

Horizontal gene transfer refers to the transfer of genetic material through a mechanism other than reproduction. This mechanism is a common source of new genes in prokaryotes, sometimes thought to contribute more to genetic variation than gene duplication.[68] It is a common means of spreading antibiotic resistance, virulence, and adaptive metabolic functions.[26][69] Although horizontal gene transfer is rare in eukaryotes, likely examples have been identified of protist and alga genomes containing genes of bacterial origin.[70][71]

Genome

The genome is the total genetic material of an organism and includes both the genes and non-coding sequences.[72]

Number of genes

Representative genome sizes for plants (green), vertebrates (blue), invertebrates (red), fungus (yellow), bacteria (purple), and viruses (grey). An inset on the right shows the smaller genomes expanded 100-fold.[73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80]

The genome size, and the number of genes it encodes varies widely between organisms. The smallest genomes occur in viruses (which can have as few as 2 protein-coding genes),[81] and viroids (which act as a single non-coding RNA gene).[82] Conversely, plants can have extremely large genomes,[83] with rice containing >46,000 protein-coding genes.[84] The total number of protein-coding genes (the Earth's proteome) is estimated to be 5 million sequences.[85]

Although the number of base-pairs of DNA in the human genome has been known since the 1960s, the estimated number of genes has changed over time as definitions of genes, and methods of detecting them have been refined. Initial theoretical predictions of the number of human genes were as high as 2,000,000.[86] Early experimental measures indicated there to be 50,000–100,000 transcribed genes (expressed sequence tags).[87] Subsequently, the sequencing in the Human Genome Project indicated that many of these transcripts were alternative variants of the same genes, and the total number of protein-coding genes was revised down to ~20,000[80] with 13 genes encoded on the mitochondrial genome.[78] Of the human genome, only 1–2% consists of protein-coding genes,[88] with the remainder being 'noncoding' DNA such as introns, retrotransposons, and noncoding RNAs.[88][89]

Essential genes

A schematic view of essential genes in lysine biosynthesis of different bacteria. The same protein may be essential in one species but not another.

Essential genes are the set of genes thought to be critical for an organism's survival.[90] This definition assumes the abundant availability of all relevant nutrients and the absence of environmental stress. Only a small portion of an organism's genes are essential. In bacteria, an estimated 250–400 genes are essential for Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, which is less than 10% of their genes.[91][92][93] Half of these genes are orthologs in both organisms and are largely involved in protein synthesis.[93] In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae the number of essential genes is slightly higher, at 1000 genes (~20% of their genes).[94] Although the number is more difficult to measure in higher eukaryotes, mice and humans are estimated to have around 2000 essential genes (~10% of their genes).[95]

Housekeeping genes are critical for carrying out basic cell functions and so are expressed at a relatively constant level (constitutively).[96] Since their expression is constant, housekeeping genes are used as experimental controls when analysing gene expression. Not all essential genes are housekeeping genes since some essential genes are developmentally regulated or expressed at certain times during the organism's life cycle.[97]

Genetic and genomic nomenclature

Gene nomenclature has been established by the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) for each known human gene in the form of an approved gene name and symbol (short-form abbreviation), which can be accessed through a database maintained by HGNC. Symbols are chosen to be unique, and each gene has only one symbol (although approved symbols sometimes change). Symbols are preferably kept consistent with other members of a gene family and with homologs in other species, particularly the mouse due to its role as a common model organism.[98]

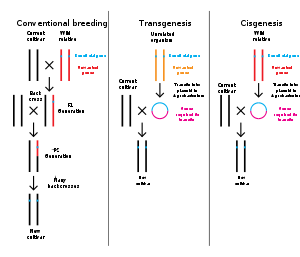

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering is the modification of an organism's genome through biotechnology. Since the 1970s, a variety of techniques have been developed to specifically add, remove and edit genes in an organism.[99] Recently developed genome engineering techniques use engineered nuclease enzymes to create targeted DNA repair in a chromosome to either disrupt or edit a gene when the break is repaired.[100][101][102][103] The related term synthetic biology is sometimes used to refer to extensive genetic engineering of an organism.[104]

Genetic engineering is now a routine research tool with model organisms. For example, genes are easily added to bacteria[105] and lineages of knockout mice with a specific gene's function disrupted are used to investigate that gene's function.[106][107] Many organisms have been genetically modified for applications in agriculture, industrial biotechnology, and medicine.

For multicellular organisms, typically the embryo is engineered which grows into the adult genetically modified organism.[108] However, the genomes of cells in an adult organism can be edited using gene therapy techniques to treat genetic diseases.

Genetic engineering is now a routine research tool with model organisms. For example, genes are easily added to bacteria[105] and lineages of knockout mice with a specific gene's function disrupted are used to investigate that gene's function.[106][107] Many organisms have been genetically modified for applications in agriculture, industrial biotechnology, and medicine.

For multicellular organisms, typically the embryo is engineered which grows into the adult genetically modified organism.[108] However, the genomes of cells in an adult organism can be edited using gene therapy techniques to treat genetic diseases.