| Stem cell | |

|---|---|

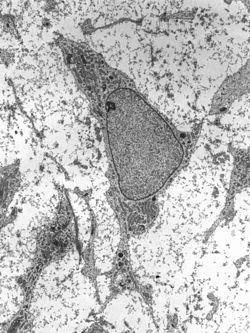

Transmission electron micrograph of an adult stem cell displaying typical ultrastructural characteristics.

|

|

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cellula praecursoria |

| MeSH | D013234 |

| TH | H1.00.01.0.00028, H2.00.01.0.00001 |

| FMA | 63368 |

In mammals, there are two broad types of stem cells: embryonic stem cells, which are isolated from the inner cell mass of blastocysts, and adult stem cells, which are found in various tissues. In adult organisms, stem cells and progenitor cells act as a repair system for the body, replenishing adult tissues. In a developing embryo, stem cells can differentiate into all the specialized cells—ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm (see induced pluripotent stem cells)—but also maintain the normal turnover of regenerative organs, such as blood, skin, or intestinal tissues.

There are three known accessible sources of autologous adult stem cells in humans:

- Bone marrow, which requires extraction by harvesting, that is, drilling into bone (typically the femur or iliac crest).

- Adipose tissue (fat cells), which requires extraction by liposuction.[citation needed]

- Blood, which requires extraction through apheresis, wherein blood is drawn from the donor (similar to a blood donation), and passed through a machine that extracts the stem cells and returns other portions of the blood to the donor.

Adult stem cells are frequently used in various medical therapies (e.g., bone marrow transplantation). Stem cells can now be artificially grown and transformed (differentiated) into specialized cell types with characteristics consistent with cells of various tissues such as muscles or nerves. Embryonic cell lines and autologous embryonic stem cells generated through somatic cell nuclear transfer or dedifferentiation have also been proposed as promising candidates for future therapies.[1] Research into stem cells grew out of findings by Ernest A. McCulloch and James E. Till at the University of Toronto in the 1960s.[2][3]

Properties

The classical definition of a stem cell requires that it possesses two properties:- Self-renewal: the ability to go through numerous cycles of cell division while maintaining the undifferentiated state.

- Potency: the capacity to differentiate into specialized cell types. In the strictest sense, this requires stem cells to be either totipotent or pluripotent—to be able to give rise to any mature cell type, although multipotent or unipotent progenitor cells are sometimes referred to as stem cells. Apart from this it is said that stem cell function is regulated in a feed back mechanism.

Self-renewal

Two mechanisms exist to ensure that a stem cell population is maintained:1. Obligatory asymmetric replication: a stem cell divides into one mother cell that is identical to the original stem cell, and another daughter cell that is differentiated.

When a stem cell self-renews it divides and does not disrupt the undifferentiated state. This self-renewal demands control of cell cycle as well as upkeep of multipotency or pluripotency, which all depends on the stem cell.[4]

2. Stochastic differentiation: when one stem cell develops into two differentiated daughter cells, another stem cell undergoes mitosis and produces two stem cells identical to the original.

Potency definition

Pluripotent, embryonic stem cells originate as

inner cell mass (ICM)

cells within a blastocyst.

These stem cells can become any tissue in the

body, excluding a placenta. Only cells from an

earlier stage of the

embryo, known as the

morula, are totipotent, able to become all

tissues in the body and the extraembryonic

placenta.

Potency specifies the differentiation potential (the potential to differentiate into different cell types) of the stem cell.[5]

- Totipotent (a.k.a. omnipotent) stem cells can differentiate into embryonic and extraembryonic cell types. Such cells can construct a complete, viable organism.[5] These cells are produced from the fusion of an egg and sperm cell. Cells produced by the first few divisions of the fertilized egg are also totipotent.[6]

- Pluripotent stem cells are the descendants of totipotent cells and can differentiate into nearly all cells,[5] i.e. cells derived from any of the three germ layers.[7]

- Multipotent stem cells can differentiate into a number of cell types, but only those of a closely related family of cells.[5]

- Oligopotent stem cells can differentiate into only a few cell types, such as lymphoid or myeloid stem cells.[5]

- Unipotent cells can produce only one cell type, their own,[5] but have the property of self-renewal, which distinguishes them from non-stem cells (e.g. progenitor cells, which cannot self-renew).

Identification

In practice, stem cells are identified by whether they can regenerate tissue. For example, the defining test for bone marrow or hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is the ability to transplant the cells and save an individual without HSCs. This demonstrates that the cells can produce new blood cells over a long term. It should also be possible to isolate stem cells from the transplanted individual, which can themselves be transplanted into another individual without HSCs, demonstrating that the stem cell was able to self-renew.Properties of stem cells can be illustrated in vitro, using methods such as clonogenic assays, in which single cells are assessed for their ability to differentiate and self-renew.[8][9] Stem cells can also be isolated by their possession of a distinctive set of cell surface markers. However, in vitro culture conditions can alter the behavior of cells, making it unclear whether the cells shall behave in a similar manner in vivo. There is considerable debate as to whether some proposed adult cell populations are truly stem cells.[citation needed]

Embryonic

Embryonic stem (ES) cells are the cells of the inner cell mass of a blastocyst, an early-stage embryo.[10] Human embryos reach the blastocyst stage 4–5 days post fertilization, at which time they consist of 50–150 cells. ES cells are pluripotent and give rise during development to all derivatives of the three primary germ layers: ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm. In other words, they can develop into each of the more than 200 cell types of the adult body when given sufficient and necessary stimulation for a specific cell type. They do not contribute to the extra-embryonic membranes or the placenta.During embryonic development these inner cell mass cells continuously divide and become more specialized. For example, a portion of the ectoderm in the dorsal part of the embryo specializes as 'neurectoderm', which will become the future central nervous system.[11] Later in development, neurulation causes the neurectoderm to form the neural tube. At the neural tube stage, the anterior portion undergoes encephalization to generate or 'pattern' the basic form of the brain. At this stage of development, the principal cell type of the CNS is considered a neural stem cell. These neural stem cells are pluripotent, as they can generate a large diversity of many different neuron types, each with unique gene expression, morphological, and functional characteristics. The process of generating neurons from stem cells is called neurogenesis. One prominent example of a neural stem cell is the radial glial cell, so named because it has a distinctive bipolar morphology with highly elongated processes spanning the thickness of the neural tube wall, and because historically it shared some glial characteristics, most notably the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).[12][13] The radial glial cell is the primary neural stem cell of the developing vertebrate CNS, and its cell body resides in the ventricular zone, adjacent to the developing ventricular system. Neural stem cells are committed to the neuronal lineages (neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes), and thus their potency is restricted.[11]

Nearly all research to date has made use of mouse embryonic stem cells (mES) or human embryonic stem cells (hES) derived from the early inner cell mass. Both have the essential stem cell characteristics, yet they require very different environments in order to maintain an undifferentiated state. Mouse ES cells are grown on a layer of gelatin as an extracellular matrix (for support) and require the presence of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) in serum media. A drug cocktail containing inhibitors to GSK3B and the MAPK/ERK pathway, called 2i, has also been shown to maintain pluripotency in stem cell culture.[14] Human ES cells are grown on a feeder layer of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and require the presence of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF or FGF-2).[15] Without optimal culture conditions or genetic manipulation,[16] embryonic stem cells will rapidly differentiate.

A human embryonic stem cell is also defined by the expression of several transcription factors and cell surface proteins. The transcription factors Oct-4, Nanog, and Sox2 form the core regulatory network that ensures the suppression of genes that lead to differentiation and the maintenance of pluripotency.[17] The cell surface antigens most commonly used to identify hES cells are the glycolipids stage specific embryonic antigen 3 and 4 and the keratan sulfate antigens Tra-1-60 and Tra-1-81. By using human embryonic stem cells to produce specialized cells like nerve cells or heart cells in the lab, scientists can gain access to adult human cells without taking tissue from patients. They can then study these specialized adult cells in detail to try and catch complications of diseases, or to study cells reactions to potentially new drugs. The molecular definition of a stem cell includes many more proteins and continues to be a topic of research.[18]

There are currently no approved treatments using embryonic stem cells. The first human trial was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in January 2009.[19] However, the human trial was not initiated until October 13, 2010 in Atlanta for spinal cord injury research. On November 14, 2011 the company conducting the trial (Geron Corporation) announced that it will discontinue further development of its stem cell programs.[20] ES cells, being pluripotent cells, require specific signals for correct differentiation—if injected directly into another body, ES cells will differentiate into many different types of cells, causing a teratoma. Differentiating ES cells into usable cells while avoiding transplant rejection are just a few of the hurdles that embryonic stem cell researchers still face.[21] Due to ethical considerations, many nations currently have moratoria or limitations on either human ES cell research or the production of new human ES cell lines. Because of their combined abilities of unlimited expansion and pluripotency, embryonic stem cells remain a theoretically potential source for regenerative medicine and tissue replacement after injury or disease.[22]

Fetal

The primitive stem cells located in the organs of fetuses are referred to as fetal stem cells.[23] There are two types of fetal stem cells:- Fetal proper stem cells come from the tissue of the fetus proper, and are generally obtained after an abortion. These stem cells are not immortal but have a high level of division and are multipotent.

- Extraembryonic fetal stem cells come from extraembryonic membranes, and are generally not distinguished from adult stem cells. These stem cells are acquired after birth, they are not immortal but have a high level of cell division, and are pluripotent.[24]

Adult

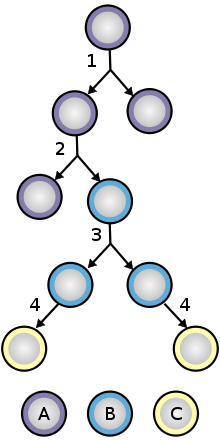

Stem cell division and differentiation. A: stem cell; B: progenitor

cell; C: differentiated cell; 1: symmetric stem cell division; 2:

asymmetric stem cell division; 3: progenitor division; 4: terminal

differentiation

Adult stem cells, also called somatic (from Greek σωματικóς, "of the body") stem cells, are stem cells which maintain and repair the tissue in which they are found.[25] They can be found in children, as well as adults.[26]

Pluripotent adult stem cells are rare and generally small in number, but they can be found in umbilical cord blood and other tissues.[27] Bone marrow is a rich source of adult stem cells,[28] which have been used in treating several conditions including liver cirrhosis,[29] chronic limb ischemia [30] and endstage heart failure.[31] The quantity of bone marrow stem cells declines with age and is greater in males than females during reproductive years.[32] Much adult stem cell research to date has aimed to characterize their potency and self-renewal capabilities.[33] DNA damage accumulates with age in both stem cells and the cells that comprise the stem cell environment. This accumulation is considered to be responsible, at least in part, for increasing stem cell dysfunction with aging (see DNA damage theory of aging).[34]

Most adult stem cells are lineage-restricted (multipotent) and are generally referred to by their tissue origin (mesenchymal stem cell, adipose-derived stem cell, endothelial stem cell, dental pulp stem cell, etc.).[35][36] Muse cells (multi-lineage differentiating stress enduring cells) are a recently discovered pluripotent stem cell type found in multiple adult tissues, including adipose, dermal fibroblasts, and bone marrow. While rare, muse cells are identifiable by their expression of SSEA-3, a marker for undifferentiated stem cells, and general mesenchymal stem cells markers such as CD105. When subjected to single cell suspension culture, the cells will generate clusters that are similar to embryoid bodies in morphology as well as gene expression, including canonical pluripotency markers Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog.[37]

Adult stem cell treatments have been successfully used for many years to treat leukemia and related bone/blood cancers through bone marrow transplants.[38] Adult stem cells are also used in veterinary medicine to treat tendon and ligament injuries in horses.[39]

The use of adult stem cells in research and therapy is not as controversial as the use of embryonic stem cells, because the production of adult stem cells does not require the destruction of an embryo. Additionally, in instances where adult stem cells are obtained from the intended recipient (an autograft), the risk of rejection is essentially non-existent. Consequently, more US government funding is being provided for adult stem cell research.[40]

Amniotic

Multipotent stem cells are also found in amniotic fluid. These stem cells are very active, expand extensively without feeders and are not tumorigenic. Amniotic stem cells are multipotent and can differentiate in cells of adipogenic, osteogenic, myogenic, endothelial, hepatic and also neuronal lines.[41] Amniotic stem cells are a topic of active research.Use of stem cells from amniotic fluid overcomes the ethical objections to using human embryos as a source of cells. Roman Catholic teaching forbids the use of embryonic stem cells in experimentation; accordingly, the Vatican newspaper "Osservatore Romano" called amniotic stem cells "the future of medicine".[42]

It is possible to collect amniotic stem cells for donors or for autologuous use: the first US amniotic stem cells bank [43][44] was opened in 2009 in Medford, MA, by Biocell Center Corporation[45][46][47] and collaborates with various hospitals and universities all over the world.[48]

Induced pluripotent

Adult stem cells have limitations with their potency; unlike ESCs, they are not able to differentiate into cells from all three germ layers. As such, they are deemed multipotent.However, reprogramming allows for the creation of pluripotent cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, from adult cells. It is important to note that these are not adult stem cells, but adult cells (e.g. epithelial cells) reprogrammed to give rise to cells with pluripotent capabilities. Using genetic reprogramming with protein transcription factors, pluripotent stem cells with ESC-like capabilities have been derived.[49][50][51] The first demonstration of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells was conducted by Shinya Yamanaka and his colleagues at Kyoto University.[52] They used the transcription factors Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4 to reprogram mouse fibroblast cells into pluripotent cells.[49][53] Subsequent work used these factors to induce pluripotency in human fibroblast cells.[54] Junying Yu, James Thomson, and their colleagues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison used a different set of factors, Oct4, Sox2, Nanog and Lin28, and carried out their experiments using cells from human foreskin.[49][55] However, they were able to replicate Yamanaka's finding that inducing pluripotency in human cells was possible.

It is important to note that iPSCs and ESCs are not equivalent. They have many similar properties, such as pluripotency and differentiation potential, the expression of pluripotency genes, epigenetic patterns, embryoid body and teratoma formation, and viable chimera formation.[52][53] However, similar does not mean they are the same. In fact, there are many differences within these properties. Importantly, the chromatin of iPSCs appears to be more "closed" or methylated than that of ESCs.[52][53] Similarly, the gene expression pattern between ESCs and iPSCs, or even iPSCs sourced from different origins.[52] There are thus questions about the "completeness" of reprogramming and the somatic memory of induced pluripotent stem cells. Despite this, inducing adult cells to be pluripotent appears to be viable.

As a result of the success of these experiments, Ian Wilmut, who helped create the first cloned animal Dolly the Sheep, has announced that he will abandon somatic cell nuclear transfer as an avenue of research.[56]

Furthermore, induced pluripotent stem cells provide several therapeutic advantages. Like ESCs, they are pluripotent. They thus have great differentiation potential; theoretically, they could produce any cell within the human body (if reprogramming to pluripotency was "complete").[52] Moreover, unlike ESCs, they potentially could allow doctors to create a pluripotent stem cell line for each individual patient.[57] In fact, frozen blood samples can be used as a source of induced pluripotent stem cells, opening a new avenue for obtaining the valued cells.[58] Patient specific stem cells allow for the screening for side effects before drug treatment, as well as the reduced risk of transplantation rejection.[57] Despite their current limited use therapeutically, iPSCs hold create potential for future use in medical treatment and research.

Lineage

To ensure self-renewal, stem cells undergo two types of cell division (see Stem cell division and differentiation diagram). Symmetric division gives rise to two identical daughter cells both endowed with stem cell properties. Asymmetric division, on the other hand, produces only one stem cell and a progenitor cell with limited self-renewal potential. Progenitors can go through several rounds of cell division before terminally differentiating into a mature cell. It is possible that the molecular distinction between symmetric and asymmetric divisions lies in differential segregation of cell membrane proteins (such as receptors) between the daughter cells.[59]An alternative theory is that stem cells remain undifferentiated due to environmental cues in their particular niche. Stem cells differentiate when they leave that niche or no longer receive those signals. Studies in Drosophila germarium have identified the signals decapentaplegic and adherens junctions that prevent germarium stem cells from differentiating.[60][61]

Treatments

Stem cell therapy is the use of stem cells to treat or prevent a disease or condition. Bone marrow transplant is a form of stem cell therapy that has been used for many years without controversy. No stem cell therapies other than bone marrow transplant are widely used.[62][63]Advantages

Stem cell treatments may lower symptoms of the disease or condition that is being treated. The lowering of symptoms may allow patients to reduce the drug intake of the disease or condition. Stem cell treatment may also provide knowledge for society to further stem cell understanding and future treatments.[64]Disadvantages

Stem cell treatments may require immunosuppression because of a requirement for radiation before the transplant to remove the person's previous cells, or because the patient's immune system may target the stem cells. One approach to avoid the second possibility is to use stem cells from the same patient who is being treated.Pluripotency in certain stem cells could also make it difficult to obtain a specific cell type. It is also difficult to obtain the exact cell type needed, because not all cells in a population differentiate uniformly. Undifferentiated cells can create tissues other than desired types.[65]

Some stem cells form tumors after transplantation;[66] pluripotency is linked to tumor formation especially in embryonic stem cells, fetal proper stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells. Fetal proper stem cells form tumors despite multipotency.[67]

Research

Some of the fundamental patents covering human embryonic stem cells are owned by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) – they are patents 5,843,780, 6,200,806, and 7,029,913 invented by James A. Thomson. WARF does not enforce these patents against academic scientists, but does enforce them against companies.[68]In 2006, a request for the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to re-examine the three patents was filed by the Public Patent Foundation on behalf of its client, the non-profit patent-watchdog group Consumer Watchdog (formerly the Foundation for Taxpayer and Consumer Rights).[68] In the re-examination process, which involves several rounds of discussion between the USPTO and the parties, the USPTO initially agreed with Consumer Watchdog and rejected all the claims in all three patents,[69] however in response, WARF amended the claims of all three patents to make them more narrow, and in 2008 the USPTO found the amended claims in all three patents to be patentable. The decision on one of the patents (7,029,913) was appealable, while the decisions on the other two were not.[70][71] Consumer Watchdog appealed the granting of the '913 patent to the USPTO's Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI) which granted the appeal, and in 2010 the BPAI decided that the amended claims of the '913 patent were not patentable.[72] However, WARF was able to re-open prosecution of the case and did so, amending the claims of the '913 patent again to make them more narrow, and in January 2013 the amended claims were allowed.[73]

In July 2013, Consumer Watchdog announced that it would appeal the decision to allow the claims of the '913 patent to the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC), the federal appeals court that hears patent cases.[74] At a hearing in December 2013, the CAFC raised the question of whether Consumer Watchdog had legal standing to appeal; the case could not proceed until that issue was resolved.[75]

Treatment

Diseases and conditions where stem cell treatment is being investigated.

Diseases and conditions where stem cell treatment is being investigated include:

- Diabetes[76]

- Rheumatoid arthritis[76]

- Parkinson's disease[76]

- Alzheimer's disease[76]

- Osteoarthritis[76]

- Stroke and traumatic brain injury repair[77]

- Learning disability due to congenital disorder [78]

- Spinal cord injury repair [79]

- Heart infarction [80]

- Anti-cancer treatments [81]

- Baldness reversal[82]

- Replace missing teeth [83]

- Repair hearing [84]

- Restore vision [85] and repair damage to the cornea[86]

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [87]

- Crohn's disease [88]

- Wound healing [89]

- Male infertility due to absence of spermatogonial stem cells [90]

In more recent years, with the ability of scientists to isolate and culture embryonic stem cells, and with scientists' growing ability to create stem cells using somatic cell nuclear transfer and techniques to create induced pluripotent stem cells, controversy has crept in, both related to abortion politics and to human cloning.

Hepatotoxicity and drug-induced liver injury account for a substantial number of failures of new drugs in development and market withdrawal, highlighting the need for screening assays such as stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells, that are capable of detecting toxicity early in the drug development process.[93]