From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Many organisms, including

aspen trees, reproduce by cloning

Cloning is the process of producing

genetically identical individuals of an

organism either naturally or artificially. In nature, many organisms produce clones through

asexual reproduction. Cloning in

biotechnology refers to the process of creating clones of organisms or copies of

cells or

DNA fragments (

molecular cloning). Beyond

biology, the term refers to the production of multiple copies of

digital media or

software.

The term

clone, invented by

J. B. S. Haldane, is derived from the

Ancient Greek word

κλών klōn, "twig", referring to the process whereby a new plant can be created from a twig. In botany, the term

lusus was traditionally used.

[1] In

horticulture, the spelling

clon was used until the twentieth century; the final

e came into use to indicate the vowel is a "long o" instead of a "short o".

[2][3] Since the term entered the popular lexicon in a more general context, the spelling

clone has been used exclusively.

Natural cloning

Cloning

is a natural form of reproduction that has allowed life forms to spread

for hundreds of millions of years. It is the reproduction method used

by

plants,

fungi, and

bacteria, and is also the way that

clonal colonies reproduce themselves.

[4][5] Examples of these organisms include

blueberry plants,

hazel trees,

the Pando trees,

[6][7] the

Kentucky coffeetree,

Myricas, and the

American sweetgum.

Molecular cloning

Molecular cloning refers to the process of making multiple molecules. Cloning is commonly used to amplify

DNA fragments containing whole

genes, but it can also be used to amplify any DNA sequence such as

promoters,

non-coding sequences and randomly fragmented DNA. It is used in a wide

array of biological experiments and practical applications ranging from

genetic fingerprinting to large scale protein production. Occasionally, the term cloning is misleadingly used to refer to the identification of the

chromosomal location of a gene associated with a particular phenotype of interest, such as in

positional cloning.

In practice, localization of the gene to a chromosome or genomic region

does not necessarily enable one to isolate or amplify the relevant

genomic sequence. To amplify any DNA sequence in a living organism, that

sequence must be linked to an

origin of replication,

which is a sequence of DNA capable of directing the propagation of

itself and any linked sequence. However, a number of other features are

needed, and a variety of specialised

cloning vectors (small piece of DNA into which a foreign DNA fragment can be inserted) exist that allow

protein production,

affinity tagging, single stranded

RNA or DNA production and a host of other molecular biology tools.

Cloning of any DNA fragment essentially involves four steps

[8]

- fragmentation - breaking apart a strand of DNA

- ligation - gluing together pieces of DNA in a desired sequence

- transfection – inserting the newly formed pieces of DNA into cells

- screening/selection – selecting out the cells that were successfully transfected with the new DNA

Although these steps are invariable among cloning procedures a number

of alternative routes can be selected; these are summarized as a

cloning strategy.

Initially, the DNA of interest needs to be isolated to provide a DNA

segment of suitable size. Subsequently, a ligation procedure is used

where the amplified fragment is inserted into a

vector (piece of DNA). The vector (which is frequently circular) is linearised using

restriction enzymes, and incubated with the fragment of interest under appropriate conditions with an enzyme called

DNA ligase.

Following ligation the vector with the insert of interest is

transfected into cells. A number of alternative techniques are

available, such as chemical sensitivation of cells,

electroporation,

optical injection and

biolistics.

Finally, the transfected cells are cultured. As the aforementioned

procedures are of particularly low efficiency, there is a need to

identify the cells that have been successfully transfected with the

vector construct containing the desired insertion sequence in the

required orientation. Modern cloning vectors include selectable

antibiotic

resistance markers, which allow only cells in which the vector has been

transfected, to grow. Additionally, the cloning vectors may contain

colour selection markers, which provide blue/white screening

(alpha-factor complementation) on

X-gal

medium. Nevertheless, these selection steps do not absolutely guarantee

that the DNA insert is present in the cells obtained. Further

investigation of the resulting colonies must be required to confirm that

cloning was successful. This may be accomplished by means of

PCR, restriction fragment analysis and/or

DNA sequencing.

Cell cloning

Cloning unicellular organisms

Cloning cell-line colonies using cloning rings

Cloning a cell means to derive a population of cells from a single

cell. In the case of unicellular organisms such as bacteria and yeast,

this process is remarkably simple and essentially only requires the

inoculation

of the appropriate medium. However, in the case of cell cultures from

multi-cellular organisms, cell cloning is an arduous task as these cells

will not readily grow in standard media.

A useful tissue culture technique used to clone distinct lineages of cell lines involves the use of cloning rings (cylinders).

[9] In this technique a single-cell suspension of cells that have been exposed to a

mutagenic agent or drug used to drive

selection

is plated at high dilution to create isolated colonies, each arising

from a single and potentially clonal distinct cell. At an early growth

stage when colonies consist of only a few cells, sterile

polystyrene rings (cloning rings), which have been dipped in grease, are placed over an individual colony and a small amount of

trypsin is added. Cloned cells are collected from inside the ring and transferred to a new vessel for further growth.

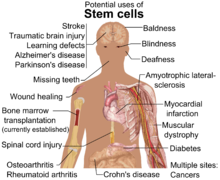

Cloning stem cells

Somatic-cell nuclear transfer,

known as SCNT, can also be used to create embryos for research or

therapeutic purposes. The most likely purpose for this is to produce

embryos for use in

stem cell research.

This process is also called "research cloning" or "therapeutic

cloning." The goal is not to create cloned human beings (called

"reproductive cloning"), but rather to harvest stem cells that can be

used to study human development and to potentially treat disease. While a

clonal human blastocyst has been created, stem cell lines are yet to be

isolated from a clonal source.

[10]

Therapeutic cloning is achieved by creating embryonic stem cells in

the hopes of treating diseases such as diabetes and Alzheimer's. The

process begins by removing the nucleus (containing the DNA) from an egg

cell and inserting a nucleus from the adult cell to be cloned.

[11]

In the case of someone with Alzheimer's disease, the nucleus from a

skin cell of that patient is placed into an empty egg. The reprogrammed

cell begins to develop into an embryo because the egg reacts with the

transferred nucleus. The embryo will become genetically identical to the

patient.

[11] The embryo will then form a blastocyst which has the potential to form/become any cell in the body.

[12]

The reason why SCNT is used for cloning is because somatic cells can

be easily acquired and cultured in the lab. This process can either add

or delete specific genomes of farm animals. A key point to remember is

that cloning is achieved when the oocyte maintains its normal functions

and instead of using sperm and egg genomes to replicate, the oocyte is

inserted into the donor’s somatic cell nucleus.

[13] The oocyte will react on the somatic cell nucleus, the same way it would on sperm cells.

[13]

The process of cloning a particular farm animal using SCNT is

relatively the same for all animals. The first step is to collect the

somatic cells from the animal that will be cloned. The somatic cells

could be used immediately or stored in the laboratory for later use.

[13]

The hardest part of SCNT is removing maternal DNA from an oocyte at

metaphase II. Once this has been done, the somatic nucleus can be

inserted into an egg cytoplasm.

[13] This creates a one-cell embryo. The grouped somatic cell and egg cytoplasm are then introduced to an electrical current.

[13]

This energy will hopefully allow the cloned embryo to begin

development. The successfully developed embryos are then placed in

surrogate recipients, such as a cow or sheep in the case of farm

animals.

[13]

SCNT is seen as a good method for producing agriculture animals for

food consumption. It successfully cloned sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs.

Another benefit is SCNT is seen as a solution to clone endangered

species that are on the verge of going extinct.

[13]

However, stresses placed on both the egg cell and the introduced

nucleus can be enormous, which led to a high loss in resulting cells in

early research. For example,

the cloned sheep Dolly

was born after 277 eggs were used for SCNT, which created 29 viable

embryos. Only three of these embryos survived until birth, and only one

survived to adulthood.

[14] As the procedure could not be automated, and had to be performed manually under a

microscope, SCNT was very resource intensive. The biochemistry involved in reprogramming the

differentiated

somatic cell nucleus and activating the recipient egg was also far from

being well understood. However, by 2014 researchers were reporting

cloning success rates of seven to eight out of ten

[15] and in 2016, a Korean Company Sooam Biotech was reported to be producing 500 cloned embryos per day.

[16]

In SCNT, not all of the donor cell's genetic information is transferred, as the donor cell's

mitochondria that contain their own

mitochondrial DNA

are left behind. The resulting hybrid cells retain those mitochondrial

structures which originally belonged to the egg. As a consequence,

clones such as Dolly that are born from SCNT are not perfect copies of

the donor of the nucleus.

Organism cloning

Organism cloning (also called reproductive cloning) refers to

the procedure of creating a new multicellular organism, genetically

identical to another. In essence this form of cloning is an asexual

method of reproduction, where fertilization or inter-gamete contact does

not take place. Asexual reproduction is a naturally occurring

phenomenon in many species, including most plants and some insects.

Scientists have made some major achievements with cloning, including the

asexual reproduction of sheep and cows. There is a lot of ethical

debate over whether or not cloning should be used. However, cloning, or

asexual propagation,

[17] has been common practice in the horticultural world for hundreds of years.

Horticultural

Propagating plants from

cuttings, such as grape vines, is an ancient form of cloning

The term

clone is used in horticulture to refer to descendants of a single plant which were produced by

vegetative reproduction or

apomixis. Many horticultural plant

cultivars are clones, having been derived from a single individual, multiplied by some process other than sexual reproduction.

[18] As an example, some European cultivars of

grapes represent clones that have been propagated for over two millennia. Other examples are

potato and

banana.

[19] Grafting

can be regarded as cloning, since all the shoots and branches coming

from the graft are genetically a clone of a single individual, but this

particular kind of cloning has not come under

ethical scrutiny and is generally treated as an entirely different kind of operation.

Many

trees,

shrubs,

vines,

ferns and other

herbaceous perennials form

clonal colonies naturally. Parts of an individual plant may become detached by

fragmentation

and grow on to become separate clonal individuals. A common example is

in the vegetative reproduction of moss and liverwort gametophyte clones

by means of

gemmae. Some vascular plants e.g.

dandelion and certain

viviparous grasses also form

seeds asexually, termed

apomixis, resulting in clonal populations of genetically identical individuals.

Parthenogenesis

Clonal derivation exists in nature in some animal species and is referred to as

parthenogenesis

(reproduction of an organism by itself without a mate). This is an

asexual form of reproduction that is only found in females of some

insects, crustaceans, nematodes,

[20] fish (for example the

hammerhead shark[21]), the

Komodo dragon[21] and

lizards.

The growth and development occurs without fertilization by a male. In

plants, parthenogenesis means the development of an embryo from an

unfertilized egg cell, and is a component process of apomixis. In

species that use the

XY sex-determination system, the offspring will always be female. An example is the little fire ant (

Wasmannia auropunctata), which is native to

Central and

South America but has spread throughout many tropical environments.

Artificial cloning of organisms

Artificial cloning of organisms may also be called

reproductive cloning.

First steps

Hans Spemann, a

German embryologist was awarded a

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

in 1935 for his discovery of the effect now known as embryonic

induction, exercised by various parts of the embryo, that directs the

development of groups of cells into particular tissues and organs. In

1928 he and his student,

Hilde Mangold, were the first to perform

somatic-cell nuclear transfer using

amphibian embryos – one of the first steps towards cloning.

[22]

Methods

Reproductive cloning generally uses "

somatic cell nuclear transfer"

(SCNT) to create animals that are genetically identical. This process

entails the transfer of a nucleus from a donor adult cell (somatic cell)

to an egg from which the nucleus has been removed, or to a cell from a

blastocyst from which the nucleus has been removed.

[23]

If the egg begins to divide normally it is transferred into the uterus

of the surrogate mother. Such clones are not strictly identical since

the somatic cells may contain mutations in their nuclear DNA.

Additionally, the

mitochondria in the

cytoplasm also contains DNA and during SCNT this mitochondrial DNA is wholly from the cytoplasmic donor's egg, thus the

mitochondrial

genome is not the same as that of the nucleus donor cell from which it

was produced. This may have important implications for cross-species

nuclear transfer in which nuclear-mitochondrial incompatibilities may

lead to death.

Artificial

embryo splitting or

embryo twinning, a

technique that creates monozygotic twins from a single embryo, is not

considered in the same fashion as other methods of cloning. During that

procedure, a donor

embryo is split in two distinct embryos, that can then be transferred via

embryo transfer. It is optimally performed at the 6- to 8-cell stage, where it can be used as an expansion of

IVF to increase the number of available embryos.

[24] If both embryos are successful, it gives rise to

monozygotic (identical) twins.

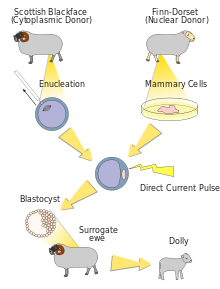

Dolly the sheep

Dolly

Dolly, a

Finn-Dorset ewe,

was the first mammal to have been successfully cloned from an adult

somatic cell. Dolly was formed by taking a cell from the udder of her

6-year old biological mother.

[25]

Dolly's embryo was created by taking the cell and inserting it into a

sheep ovum. It took 434 attempts before an embryo was successful.

[26] The embryo was then placed inside a female sheep that went through a normal pregnancy.

[27] She was cloned at the

Roslin Institute in

Scotland by British scientists Sir

Ian Wilmut and

Keith Campbell

and lived there from her birth in 1996 until her death in 2003 when she

was six. She was born on 5 July 1996 but not announced to the world

until 22 February 1997.

[28] Her

stuffed remains were placed at Edinburgh's

Royal Museum, part of the

National Museums of Scotland.

[29]

Dolly was publicly significant because the effort showed that genetic

material from a specific adult cell, programmed to express only a

distinct subset of its genes, can be reprogrammed to grow an entirely

new organism. Before this demonstration, it had been shown by John

Gurdon that nuclei from differentiated cells could give rise to an

entire organism after transplantation into an enucleated egg.

[30] However, this concept was not yet demonstrated in a mammalian system.

The first mammalian cloning (resulting in Dolly the sheep) had a

success rate of 29 embryos per 277 fertilized eggs, which produced three

lambs at birth, one of which lived. In a bovine experiment involving 70

cloned calves, one-third of the calves died young. The first

successfully cloned horse,

Prometea, took 814 attempts. Notably, although the first

[clarification needed] clones were frogs, no adult cloned frog has yet been produced from a somatic adult nucleus donor cell.

There were early claims that

Dolly the sheep

had pathologies resembling accelerated aging. Scientists speculated

that Dolly's death in 2003 was related to the shortening of

telomeres, DNA-protein complexes that protect the end of linear

chromosomes. However, other researchers, including

Ian Wilmut

who led the team that successfully cloned Dolly, argue that Dolly's

early death due to respiratory infection was unrelated to deficiencies

with the cloning process. This idea that the nuclei have not

irreversibly aged was shown in 2013 to be true for mice.

[31]

Dolly was named after performer

Dolly Parton because the cells cloned to make her were from a

mammary gland cell, and Parton is known for her ample cleavage.

[32]

Species cloned

The modern cloning techniques involving

nuclear transfer have been successfully performed on several species. Notable experiments include:

- Tadpole: (1952) Robert Briggs and Thomas J. King had successfully cloned northern leopard frogs: thirty-five complete embryos and twenty-seven tadpoles from one-hundred and four successful nuclear transfers.[33][34]

- Carp: (1963) In China, embryologist Tong Dizhou produced the world's first cloned fish

by inserting the DNA from a cell of a male carp into an egg from a

female carp. He published the findings in a Chinese science journal.[35]

- Mice: (1986) A mouse was successfully cloned from an early embryonic cell. Soviet

scientists Chaylakhyan, Veprencev, Sviridova, and Nikitin had the mouse

"Masha" cloned. Research was published in the magazine "Biofizika"

volume ХХХII, issue 5 of 1987.[clarification needed][36][37]

- Sheep: Marked the first mammal being cloned (1984) from early embryonic cells by Steen Willadsen. Megan and Morag[38] cloned from differentiated embryonic cells in June 1995 and Dolly the sheep from a somatic cell in 1996.[39][35]

- Rhesus monkey: Tetra (January 2000) from embryo splitting and not nuclear transfer. More akin to artificial formation of twins.[40][41]

- Pig: the first cloned pigs (March 2000).[42] By 2014, BGI in China was producing 500 cloned pigs a year to test new medicines.[43]

- Gaur: (2001) was the first endangered species cloned.[44]

- Cattle: Alpha and Beta (males, 2001) and (2005) Brazil[45]

- Cat: CopyCat "CC" (female, late 2001), Little Nicky, 2004, was the first cat cloned for commercial reasons[46]

- Rat: Ralph, the first cloned rat (2003)[47]

- Mule: Idaho Gem, a john mule born 4 May 2003, was the first horse-family clone.[48]

- Horse: Prometea, a Haflinger female born 28 May 2003, was the first horse clone.[49]

- Dog: Snuppy, a male Afghan hound was the first cloned dog (2005).[50]

- Wolf: Snuwolf and Snuwolffy, the first two cloned female wolves (2005).[51]

- Water buffalo: Samrupa was the first cloned water buffalo. It was born on 6 February 2009, at India's Karnal National Diary Research Institute but died five days later due to lung infection.[52]

- Pyrenean ibex (2009) was the first extinct animal to be cloned back to life; the clone lived for seven minutes before dying of lung defects.[53][54]

- Camel: (2009) Injaz, is the first cloned camel.[55]

- Pashmina goat: (2012) Noori, is the first cloned pashmina goat. Scientists at the faculty of veterinary sciences and animal husbandry of Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir

successfully cloned the first Pashmina goat (Noori) using the advanced

reproductive techniques under the leadership of Riaz Ahmad Shah.[56]

- Goat: (2001) Scientists of Northwest A&F University successfully cloned the first goat which use the adult female cell.[57]

- Gastric brooding frog: (2013) The gastric brooding frog, Rheobatrachus silus, thought to have been extinct since 1983 was cloned in Australia, although the embryos died after a few days.[58]

- Macaque monkey: (2017) First successful cloning of a primate species using nuclear transfer, with the birth of two live clones, named Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua. Conducted in China in 2017, and reported in January 2018.[59][60][61][62]

Human cloning

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of a

human. The term is generally used to refer to artificial human cloning,

which is the reproduction of human cells and tissues. It does not refer

to the natural conception and delivery of

identical twins. The possibility of human cloning has raised

controversies. These ethical concerns have prompted several nations to pass

legislature

regarding human cloning and its legality. As of right now, scientists

have no intention of trying to clone people and they believe their

results should spark a wider discussion about the laws and regulations

the world needs to regulate cloning.

[63]

Two commonly discussed types of theoretical human cloning are

therapeutic cloning and

reproductive cloning.

Therapeutic cloning would involve cloning cells from a human for use in

medicine and transplants, and is an active area of research, but is not

in medical practice anywhere in the world, as of 2014. Two common

methods of therapeutic cloning that are being researched are

somatic-cell nuclear transfer and, more recently,

pluripotent stem cell induction. Reproductive cloning would involve making an entire cloned human, instead of just specific cells or tissues.

[64]

Ethical issues of cloning

There are a variety of

ethical positions regarding the possibilities of cloning, especially

human cloning. While many of these views are

religious in origin, the questions raised by cloning are faced by

secular

perspectives as well. Perspectives on human cloning are theoretical, as

human therapeutic and reproductive cloning are not commercially used;

animals are currently cloned in laboratories and in livestock

production.

Advocates support development of therapeutic cloning in order to

generate tissues and whole organs to treat patients who otherwise cannot

obtain transplants,

[65] to avoid the need for

immunosuppressive drugs,

[64] and to stave off the effects of aging.

[66] Advocates for reproductive cloning believe that parents who cannot otherwise procreate should have access to the technology.

[67]

Opponents of cloning have concerns that technology is not yet developed enough to be safe

[68] and that it could be prone to abuse (leading to the generation of humans from whom organs and tissues would be harvested),

[69][70] as well as concerns about how cloned individuals could integrate with families and with society at large.

[71][72]

Religious groups are divided, with some opposing the technology as

usurping "God's place" and, to the extent embryos are used, destroying a

human life; others support therapeutic cloning's potential life-saving

benefits.

[73][74]

Cloning of animals is opposed by animal-groups due to the number of

cloned animals that suffer from malformations before they die,

[75][76] and while food from cloned animals has been approved by the US FDA,

[77][78] its use is opposed by groups concerned about food safety.

[79][80][81]

Cloning extinct and endangered species

Cloning, or more precisely, the reconstruction of functional DNA from

extinct species has, for decades, been a dream. Possible implications of this were dramatized in the 1984 novel

Carnosaur and the 1990 novel

Jurassic Park.

[82][83] The best current cloning techniques have an average success rate of 9.4 percent

[84] (and as high as 25 percent

[31]) when working with familiar species such as mice,

[note 1] while cloning wild animals is usually less than 1 percent successful.

[87] Several tissue banks have come into existence, including the "

Frozen Zoo" at the

San Diego Zoo, to store frozen tissue from the world's rarest and most endangered species.

[82][88][89]

In 2001, a cow named Bessie gave birth to a cloned Asian

gaur, an endangered species, but the calf died after two days. In 2003, a

banteng

was successfully cloned, followed by three African wildcats from a

thawed frozen embryo. These successes provided hope that similar

techniques (using surrogate mothers of another species) might be used to

clone extinct species. Anticipating this possibility, tissue samples

from the last

bucardo (

Pyrenean ibex) were frozen in

liquid nitrogen

immediately after it died in 2000. Researchers are also considering

cloning endangered species such as the giant panda and cheetah.

In 2002, geneticists at the

Australian Museum announced that they had replicated DNA of the

thylacine (Tasmanian tiger), at the time extinct for about 65 years, using

polymerase chain reaction.

[90]

However, on 15 February 2005 the museum announced that it was stopping

the project after tests showed the specimens' DNA had been too badly

degraded by the (

ethanol)

preservative. On 15 May 2005 it was announced that the thylacine

project would be revived, with new participation from researchers in

New South Wales and

Victoria.

In 2003, for the first time, an extinct animal, the Pyrenean ibex

mentioned above was cloned, at the Centre of Food Technology and

Research of Aragon, using the preserved frozen cell nucleus of the skin

samples from 2001 and domestic goat egg-cells. The ibex died shortly

after birth due to physical defects in its lungs.

[91]

One of the most anticipated targets for cloning was once the

woolly mammoth,

but attempts to extract DNA from frozen mammoths have been

unsuccessful, though a joint Russo-Japanese team is currently working

toward this goal. In January 2011, it was reported by Yomiuri Shimbun

that a team of scientists headed by Akira Iritani of Kyoto University

had built upon research by Dr. Wakayama, saying that they will extract

DNA from a mammoth carcass that had been preserved in a Russian

laboratory and insert it into the egg cells of an African elephant in

hopes of producing a mammoth embryo. The researchers said they hoped to

produce a baby mammoth within six years.

[92][93] It was noted, however that the result, if possible, would be an elephant-mammoth hybrid rather than a true mammoth.

[94] Another problem is the survival of the reconstructed mammoth:

ruminants rely on a

symbiosis with specific

microbiota in their stomachs for digestion.

[94]

Scientists at the

University of Newcastle and

University of New South Wales announced in March 2013 that the very recently extinct

gastric-brooding frog would be the subject of a cloning attempt to resurrect the species.

[95]

Many such "de-extinction" projects are described in the

Long Now Foundation's Revive and Restore Project.

[96]

Lifespan

After

an eight-year project involving the use of a pioneering cloning

technique, Japanese researchers created 25 generations of healthy cloned

mice with normal lifespans, demonstrating that clones are not

intrinsically shorter-lived than naturally born animals.

[31][97]

Other sources have noted that the offspring of clones tend to be

healthier than the original clones and indistinguishable from animals

produced naturally.

[98]

Dolly the sheep was created from a six year old cell sample from a

mammary gland. Because of this, she aged quicker than other naturally

born animals because she was started from already aging cells. She died

prematurely at six years old, not only from her age but from respiratory

issues and severe arthritis.

A detailed study released in 2016 and less detailed studies by others

suggest that once cloned animals get past the first month or two of

life they are generally healthy. However, early pregnancy loss and

neonatal losses are still greater with cloning than natural conception

or assisted reproduction (IVF). Current research is attempting to

overcome these problems.

[32]

In popular culture

In

Jurassic Park (1993), dinosaurs are resurrected through cloning for entertainment

Discussion of cloning in the popular media often presents the subject

negatively. In an article in the 8 November 1993 article of

Time, cloning was portrayed in a negative way, modifying Michelangelo's

Creation of Adam to depict Adam with five identical hands.

[99] Newsweek's 10 March 1997 issue also critiqued the ethics of human cloning, and included a graphic depicting identical babies in beakers.

[100]

The concept of cloning, particularly human cloning, has featured a wide variety of

science fiction works. An early fictional depiction of cloning is

Bokanovsky's Process which features in

Aldous Huxley's 1931 dystopian novel

Brave New World. The process is applied to fertilized human

eggs in vitro, causing them to split into identical genetic copies of the original.

[101][102] Following renewed interest in cloning in the 1950s, the subject was explored further in works such as

Poul Anderson's 1953 story

UN-Man, which describes a technology called "exogenesis", and

Gordon Rattray Taylor's book

The Biological Time Bomb, which popularised the term "cloning" in 1963.

[103]

Cloning is a recurring theme in a number of contemporary science fiction films, ranging from action films such as

Jurassic Park (1993),

Alien Resurrection (1997),

The 6th Day (2000),

Resident Evil (2002),

Star Wars: Episode II (2002) and

The Island (2005), to comedies such as

Woody Allen's 1973 film

Sleeper.

[104]

The process of cloning is represented variously in fiction. Many

works depict the artificial creation of humans by a method of growing

cells from a tissue or DNA sample; the replication may be instantaneous,

or take place through slow growth of human embryos in

artificial wombs. In the long-running British television series

Doctor Who, the

Fourth Doctor and his companion

Leela were cloned in a matter of seconds from DNA samples ("

The Invisible Enemy", 1977) and then — in an apparent

homage to the 1966 film

Fantastic Voyage

— shrunk to microscopic size in order to enter the Doctor's body to

combat an alien virus. The clones in this story are short-lived, and can

only survive a matter of minutes before they expire.

[105] Science fiction films such as

The Matrix and

Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones have featured scenes of human

foetuses being cultured on an industrial scale in mechanical tanks.

[106]

Cloning humans from body parts is also a common theme in science

fiction. Cloning features strongly among the science fiction conventions

parodied in Woody Allen's

Sleeper, the plot of which centres around an attempt to clone an assassinated dictator from his disembodied nose.

[107] In the 2008

Doctor Who story "

Journey's End", a duplicate version of the

Tenth Doctor spontaneously grows from his severed hand, which had been cut off in a sword fight during an earlier episode.

[108]

After the death of her beloved 14-year old Coton de Tulear named Samantha in late 2017,

Barbra Streisand

announced that she had cloned the dog, and was now "waiting for [the

two cloned pups] to get older so [she] can see if they have [Samantha's]

brown eyes and her seriousness."

[109] The operation cost $50,000 through the pet cloning company ViaGen.

Cloning and identity

Science fiction has used cloning, most commonly and specifically

human cloning, to raise the controversial questions of identity.

[110][111] A Number is a 2002 play by

English playwright Caryl Churchill which addresses the subject of human cloning and identity, especially

nature and nurture. The story, set in the near future, is structured around the conflict

between a father (Salter) and his sons (Bernard 1, Bernard 2, and

Michael Black) – two of whom are clones of the first one.

A Number was adapted by Caryl Churchill for television, in a co-production between the

BBC and

HBO Films.

[112]

In 2012, a Japanese television series named "Bunshin" was created.

The story's main character, Mariko, is a woman studying child welfare in

Hokkaido. She grew up always doubtful about the love from her mother,

who looked nothing like her and who died nine years before. One day, she

finds some of her mother's belongings at a relative's house, and heads

to Tokyo to seek out the truth behind her birth. She later discovered

that she was a clone.

[113]

In the 2013 television series

Orphan Black, cloning is used as a scientific study on the behavioral adaptation of the clones.

[114] In a similar vein, the book

The Double by Nobel Prize winner

José Saramago explores the emotional experience of a man who discovers that he is a clone.

[115]

Cloning as resurrection

Cloning has been used in fiction as a way of recreating historical figures. In the 1976

Ira Levin novel

The Boys from Brazil and its

1978 film adaptation,

Josef Mengele uses cloning to create copies of

Adolf Hitler.

[116]

In

Michael Crichton's 1990 novel

Jurassic Park, which spawned a

series of Jurassic Park feature films, a bioengineering company develops a technique to resurrect extinct species of

dinosaurs by creating cloned creatures using DNA extracted from

fossils. The cloned dinosaurs are used to populate the Jurassic Park

wildlife park

for the entertainment of visitors. The scheme goes disastrously wrong

when the dinosaurs escape their enclosures. Despite being selectively

cloned as females to prevent them from breeding, the dinosaurs develop

the ability to reproduce through

parthenogenesis.

[117]

Cloning for warfare

The use of cloning for military purposes has also been explored in several fictional works. In

Doctor Who, an alien race of armour-clad, warlike beings called

Sontarans was introduced in the 1973 serial "

The Time Warrior".

Sontarans are depicted as squat, bald creatures who have been

genetically engineered for combat. Their weak spot is a "probic vent", a

small socket at the back of their neck which is associated with the

cloning process.

[118] The concept of cloned soldiers being bred for combat was revisited in "

The Doctor's Daughter" (2008), when the Doctor's DNA is used to create a female warrior called

Jenny.

[119]

The 1977 film

Star Wars was set against the backdrop of a historical conflict called the

Clone Wars. The events of this war were not fully explored until the prequel films

Attack of the Clones (2002) and

Revenge of the Sith (2005), which depict a

space war waged by a massive army of heavily armoured

clone troopers that leads to the foundation of the

Galactic Empire.

Cloned soldiers are "manufactured" on an industrial scale, genetically

conditioned for obedience and combat effectiveness. It is also revealed

that the popular character

Boba Fett originated as a clone of

Jango Fett, a mercenary who served as the genetic template for the clone troopers.

[120][121]

Cloning has appeared in many video games. In

Metal Gear Solid, the characters

Solid Snake and

Liquid Snake were born in a secret project as cloned soldiers. In

Halo, cloning technology is shown to recreate organs. In addition, the

Factions of Halo#United Nations Space Command

uses cloning when it abducts children to train as supersoldiers. Here,

non-clone children are trained as soldiers while the clones covertly

replace the abducted children at home.

Cloning for exploitation

A recurring sub-theme of cloning fiction is the use of clones as a supply of

organs for

transplantation. The 2005

Kazuo Ishiguro novel

Never Let Me Go and the

2010 film adaption[122] are set in an

alternate history

in which cloned humans are created for the sole purpose of providing

organ donations to naturally born humans, despite the fact that they are

fully sentient and self-aware. The 2005 film

The Island[123]

revolves around a similar plot, with the exception that the clones are

unaware of the reason for their existence. In Raymond Han's 2017 novel,

The Mind Clones Trilogy,

[124]

a dictator who suffered a terminal illness sought to implant his mind

clone into his son's mind so that he could continue to rule the country.

In another part of the trilogy, usurpers plotted to replace members of

the Chinese Politburo Standing Committee using look-alike human clones.

The exploitation of human clones for dangerous and undesirable work was examined in the 2009 British science fiction film

Moon.

[125] In the futuristic novel

Cloud Atlas and subsequent

film,

one of the story lines focuses on a genetically-engineered fabricant

clone named Sonmi~451, one of millions raised in an artificial

"wombtank," destined to serve from birth. She is one of thousands

created for manual and

emotional labor;

Sonmi herself works as a server in a restaurant. She later discovers

that the sole source of food for clones, called 'Soap', is manufactured

from the clones themselves.

[126]