May 1, 2001 by Isaac L. Chuang, Neil Gershenfeld

Original link: http://www.kurzweilai.net/quantum-computing-with-molecules

By taking advantage of nuclear magnetic resonance, scientists can coax the molecules in some ordinary liquids to serve as an extraordinary type of computer.

Original link: http://www.kurzweilai.net/quantum-computing-with-molecules

By taking advantage of nuclear magnetic resonance, scientists can coax the molecules in some ordinary liquids to serve as an extraordinary type of computer.

Originally published June 1998 in Scientific American. Published on KurzweilAI.net May 1, 2001.

Factoring a number with 400 digits–a numerical feat needed to break some security codes–would take even the fastest supercomputer in existence billions of years. But a newly conceived type of computer, one that exploits quantum-mechanical interactions, might complete the task in a year or so, thereby defeating many of the most sophisticated encryption schemes in use. Sensitive data are safe for the time being, because no one has been able to build a practical quantum computer. But researchers have now demonstrated the feasibility of this approach. Such a computer would look nothing like the machine that sits on your desk; surprisingly, it might resemble the cup of coffee at its side.

We and several other research groups believe quantum computers based on the molecules in a liquid might one day overcome many of the limits facing conventional computers. Roadblocks to improving conventional computers will ultimately arise from the fundamental physical bounds to miniaturization (for example, because transistors and electrical wiring cannot be made slimmer than the width of an atom). Or they may come about for practical reasons–most likely because the facilities for fabricating still more powerful microchips will become prohibitively expensive. Yet the magic of quantum mechanics might solve both these problems.

The advantage of quantum computers arises from the way they encode a bit, the fundamental unit of information. The state of a bit in a classical digital computer is specified by one number, 0 or 1. An n-bit binary word in a typical computer is accordingly described by a string of n zeros and ones. A quantum bit, called a qubit, might be represented by an atom in one of two different states, which can also be denoted as 0 or 1. Two qubits, like two classical bits, can attain four different well-defined states (0 and 0, 0 and 1, 1 and 0, or 1 and 1).

But unlike classical bits, qubits can exist simultaneously as 0 and 1, with the probability for each state given by a numerical coefficient. Describing a two-qubit quantum computer thus requires four coefficients. In general, n qubits demand 2n numbers, which rapidly becomes a sizable set for larger values of n. For example, if n equals 50, about 1015 numbers are required to describe all the probabilities for all the possible states of the quantum machine–a number that exceeds the capacity of the largest conventional computer. A quantum computer promises to be immensely powerful because it can be in multiple states at once–a phenomenon called superposition–and because it can act on all its possible states simultaneously. Thus, a quantum computer could naturally perform myriad operations in parallel, using only a single processing unit.

Action at a Distance

Another property of qubits is even more bizarre–and useful. Imagine a physical process that emits two photons (packets of light), one to the left and the other to the right, with the two photons having opposite orientations (polarizations) for their oscillating electrical fields. Until detected, the polarization of each of the photons is indeterminate. As noted by Albert Einstein and others early in the century, at the instant a person measures the polarization for one photon, the state of the other polarization becomes immediately fixed–no matter how far away it is. Such instantaneous action at a distance is curious indeed. This phenomenon allows quantum systems to develop a spooky connection, a so-called entanglement, that effectively serves to wire together the qubits in a quantum computer. This same property allowed Anton Zeilinger and his colleagues at the University of Innsbruck in Austria to perform a remarkable demonstration of quantum teleportation last year.In 1994 Peter W. Shor of AT&T deduced how to take advantage of entanglement and superposition to find the prime factors of an integer. He found that a quantum computer could, in principle, accomplish this task much faster than the best classical calculator ever could. His discovery had an enormous impact. Suddenly, the security of encryption systems that depend on the difficulty of factoring large numbers became suspect. And because so many financial transactions are currently guarded with such encryption schemes, Shor’s result sent tremors through a cornerstone of the world’s electronic economy.

Certainly no one had imagined that such a breakthrough would come from outside the disciplines of computer science or number theory. So Shor’s algorithm prompted computer scientists to begin learning about quantum mechanics, and it sparked physicists to start dabbling in computer science.

Spin Doctoring

The researchers contemplating Shor’s discovery all understood that building a useful quantum computer was going to be fiendishly difficult. The problem is that almost any interaction a quantum system has with its environment–say, an atom colliding with another atom or a stray photon–constitutes a measurement. The superposition of quantum-mechanical states then collapses into a single very definite state–the one that is detected by an observer. This phenomenon, known as decoherence, makes further quantum calculation impossible. Thus, the inner workings of a quantum computer must somehow be separated from its surroundings to maintain coherence. But they must also be accessible so that calculations can be loaded, executed and read out.Prior work, including elegant experiments by Christopher R. Monroe and David J. Wineland of the National Institute of Standards and Technology and by H. Jeff Kimble of the California Institute of Technology, attempted to solve this problem by carefully isolating the quantum-mechanical heart of their computers. For example, magnetic fields can trap a few charged particles, which can then be cooled into pure quantum states. But even such heroic experimental efforts have demonstrated only rudimentary quantum operations, because these novel devices involve only a few bits and because they lose coherence very quickly.

DESKTOP QUANTUM COMPUTER

So how then can a quantum-mechanical computer ever be exploited if it needs to be so well isolated from its surroundings? Last year we realized that an ordinary liquid could perform all the steps in a quantum computation: loading in an initial condition, applying logical operations to entangled superpositions and reading out the final result. Along with another group at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, we found that nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques (similar to the methods used for magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI) could manipulate quantum information in what appear to be classical fluids.It turns out that filling a test tube with a liquid made up of appropriate molecules–that is, using a huge number of individual quantum computers instead of just one–neatly addresses the problem of decoherence. By representing each qubit with a vast collection of molecules, one can afford to let measurements interact with a few of them. In fact, chemists, who have used NMR for decades to study complicated molecules, have been doing quantum computing all along without realizing it.

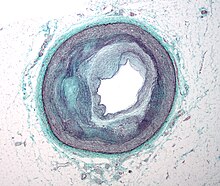

Nuclear magnetic resonance operates on quantum particles in the atomic nuclei within the molecules of the fluid. Particles with “spin” act like tiny bar magnets and will line up with an externally applied magnetic field. Two alternative alignments (parallel or antiparallel to the external field) correspond to two quantum states with different energies, which naturally constitute a qubit. One might suppose that the parallel spin corresponds to the number 1 and the antiparallel spin to the number 0. The parallel spin has lower energy than the antiparallel spin, by an amount that depends on the strength of the externally applied magnetic field. Normally, opposing spins are present in equal numbers in a fluid. But the applied field favors the creation of parallel spins, so a tiny imbalance between the two states ensues. This minute excess, perhaps just one in a million nuclei, is measured during an NMR experiment.

In addition to this fixed magnetic backdrop, NMR procedures also utilize varying electromagnetic fields. By applying an oscillating field of just the right frequency (determined by the magnitude of the fixed field and the intrinsic properties of the particle involved), certain spins can be made to flip between states. This feature allows the nuclear spins to be redirected at will.

For instance, protons (hydrogen nuclei) placed within a fixed magnetic field of 10 tesla can be induced to change direction by a magnetic field that oscillates at about 400 megahertz–that is, at radio frequencies. While turned on, usually only for a few millionths of a second, such radio waves will rotate the nuclear spins about the direction of the oscillating field, which is typically arranged to lie at right angles to the fixed field. If the oscillating radio-frequency pulse lasts just long enough to rotate the spins by 180 degrees, the excess of magnetic nuclei previously aligned in parallel with the fixed field will now point in the opposite, antiparallel direction. A pulse of half that duration would leave the particles with an equal probability of being aligned parallel or antiparallel.

In quantum-mechanical terms, the spins would be in both states, 0 and 1, simultaneously. The usual classical rendition of this situation pictures the particle’s spin axis pointing at 90 degrees to the fixed magnetic field. Then, like a child’s top that is canted far from the vertical force of gravity, the spin axis of the particle itself rotates, or precesses, about the magnetic field, looping around with a characteristic frequency. In doing so, it emits a feeble radio signal, which the NMR apparatus can detect.

In fact, the particles in an NMR experiment feel more than just the applied fields, because each tiny atomic nucleus influences the magnetic field in its vicinity. In a liquid, the constant motion of the molecules relative to one another evens out most of these local magnetic ripples. But one magnetic nucleus can affect another in the same molecule when it disturbs the electrons orbiting around them both.

Rather than being a problem, this interaction within a molecule proves quite useful. It allows a logic “gate,” the basic unit of a computation, to be readily constructed using two nuclear spins. For our two-spin experiments, we used chloroform (CHCl3). We were interested in taking advantage of the interaction between the spins of the hydrogen and carbon nuclei. Because the nucleus of common carbon, carbon 12, has no spin, we used chloroform containing carbon with one extra neutron, which imparts an overall spin to it.

Suppose the spin of the hydrogen is directed either up or down, parallel or antiparallel to a vertically applied magnetic field, whereas the spin of the carbon is arranged so that it definitely points up, parallel to this fixed magnetic field. A properly designed radio-frequency pulse can rotate the carbon’s spin downward into the horizontal plane. The carbon nucleus will then precess about the vertical, with a speed of rotation that depends on whether the hydrogen nucleus in that molecule also happens to be parallel to the applied field. After a certain short time, the carbon will point either in one direction or exactly the opposite, depending on whether the spin of the neighboring hydrogen was up or down. At that instant, we apply another radio-frequency pulse to rotate the carbon nucleus another 90 degrees. That maneuver then flips the carbon nucleus into the down position if the adjacent hydrogen was up or into the up position if the hydrogen was down.

MAGNETIC NUCLEUS

This set of operations corresponds to what electrical engineers call an exclusive-OR logic gate, something that is perhaps better termed a controlled-NOT gate (because the state of one input controls whether the signal presented at the other input is inverted at the output). Whereas classical computers require similar two-input gates as well as simpler one-input NOT gates in their construction, a group of researchers showed in 1995 that quantum computations can indeed be performed by means of rotations applied to individual spins and controlled-NOT gates. In fact, this type of quantum logic gate is far more versatile than its classical equivalent, because the spins on which it is based can be in superpositions of up and down states. Quantum computation can therefore operate simultaneously on a combination of seemingly incompatible inputs.Two Things at Once

In 1996 we set out with Mark G. Kubinec of the University of California at Berkeley to build a modest two-bit quantum-mechanical computer made from a thimbleful of chloroform. Preparing the input for even this two-bit device requires considerable effort. A series of radio-frequency pulses must transform the countless nuclei in the experimental liquid into a collection that has its excess spins arranged just right. Then these qubits must be sequentially modified. In contrast to the bits in a conventional electronic computer, which migrate in an orderly way through arrays of logic gates as the calculation proceeds, these qubits do not go anywhere. Instead the logic gates are brought to them using various NMR manipulations. In essence, the program to be executed is compiled into a series of radio-frequency pulses.The first computation we accomplished that exercised the unique abilities of quantum-mechanical computing followed an ingenious search algorithm devised by Lov K. Grover of Bell Laboratories. A typical computer searching for a desired item that is lost somewhere in a database of n items would take, on average, about n/2 tries to find it. Amazingly, Grover’s quantum search can pinpoint the desired item in roughly tries. As an example of this savings, we demonstrated that our two-qubit quantum computer could find a marked item hidden in a list of four possibilities in a single step. The classical solution to this problem is akin to opening a two-bit padlock by guessing: one would be unlikely to find the right combination on the first attempt. In fact, the classical method of solution would require, on average, between two and three tries.

A basic limitation of the chloroform computer is clearly its small number of qubits. The number of qubits could be expanded, but n could be no larger than the number of atoms in the molecule employed. With existing NMR equipment, the biggest quantum computers one can construct would have only about 10 qubits (because at room temperature the strength of the desired signal decreases rapidly as the number of magnetic nuclei in the molecule increases). Special NMR instrumentation designed around a suitable molecule could conceivably extend that number by a factor of three or four. But to create still larger computers, other techniques, such as optical pumping, would be needed to “cool” the spins. That is, the light from a suitable laser could help align the nuclei as effectively as removing the thermal motion of the molecules–but without actually freezing the liquid and ruining its ability to maintain long coherence times.

So larger quantum computers might be built. But how fast would they be? The effective cycle time of a quantum computer is determined by the slowest rate at which the spins flip around. This rate is, in turn, dictated by the interactions between spins and typically ranges from hundreds of cycles a second to a few cycles a second. Although running only a handful of clock cycles each second might seem awfully sluggish compared with the megahertz speed of conventional computers, a quantum computer with enough qubits would achieve such massive quantum parallelism that it would still factor a 400-digit number in about a year.

CONTROLLED-NOT LOGIC GATE

Given such promise, we have thought a great deal about how such a quantum computer could be physically constructed. Finding molecules with enough atoms is not a problem. The frustration is that as the size of a molecule increases, the interactions between the most distant spins eventually become too weak to use for logic gates. Yet all is not lost. Seth Lloyd of M.I.T. has shown that powerful quantum computers could, in principle, be built even if each atom interacts with only a few of its nearest neighbors, much like today’s parallel computers. This kind of quantum computer might be made of long hydrocarbon molecules, also using NMR techniques. The spins in the many atomic nuclei, which are linked into long chains, would then serve as the qubits.Another barrier to practical NMR computation is coherence. Rotating nuclei in a fluid will, like synchronized swimmers robbed of proper cues, begin to lose coherence after an interval of a few seconds to a few minutes. The longest coherence times for fluids, compared with the characteristic cycle times, suggest that about 1,000 operations could be performed while still preserving quantum coherence. Fortunately, it is possible to extend this limit by adding extra qubits to correct for quantum errors.

Although classical computers use extra bits to detect and correct errors, many experts were surprised when Shor and others showed that the same can be done quantum-mechanically. They had naively expected that quantum error correction would require measuring the state of the system and hence wrecking its quantum coherence. It turns out, however, that quantum errors can be corrected within the computer without the operator ever having to read the erroneous state.

Still, reaching sizes that make quantum computers large enough to compete with the fastest classical computers will be especially difficult. But we believe the challenge is well worth taking on. Quantum computers, even modest ones, will provide superb natural laboratories in which to study the principles of quantum mechanics. With these devices, researchers will be able to investigate other quantum systems that are of fundamental interest simply by running the appropriate program.

CRACKING A COMBINATION

Ironically, such quantum computers may help scientists and engineers solve the problems they encounter when they try to design conventional microchips with exceedingly small transistors, which behave quantum-mechanically when reduced in size to their limits.Classical computers have great difficulty solving such problems of quantum mechanics. But quantum computers might do so easily. It was this possibility that inspired the late Richard Feynman of Caltech to ponder early on whether quantum computers could actually be built.

Perhaps the most satisfying aspect is the realization that constructing such quantum computers will not require the fabrication of tiny circuits of atomic scale or any other sophisticated advance in nanotechnology. Indeed, nature has already completed the hardest part of the process by assembling the basic components. All along, ordinary molecules have known how to do a remarkable kind of computation. People were just not asking them the right questions.

Related Links

General Reference on Quantum ComputingZeilinger’s Teleportation Experiment

Quantum Computing Takes Practical Leap

Further Reading

PRINCIPLES OF MAGNETIC RESONANCE. Third edition. Charles P. Slichter. Springer-Verlag, 1992.QUANTUM INFORMATION AND COMPUTATION. C. H. Bennett in Physics Today, Vol. 48, No. 10, pages 24-30; October 1995.

QUANTUM-MECHANICAL COMPUTERS. Seth Lloyd in Scientific American, Vol. 273, No. 4, pages 140-145; October 1995.

BULK SPIN-RESONANCE QUANTUM COMPUTATION. N. A. Gershenfeld and I. L. Chuang in Science, Vol. 275, pages 350-356; January 17, 1997.

QUANTUM MECHANICS HELPS IN SEARCHING FOR A NEEDLE IN A HAYSTACK. L. K. Grover in Physical Review Letters, Vol. 79, No. 2, pages 325-328; July 14, 1997.

The Authors

NEIL GERSHENFELD and ISAAC L. CHUANG have worked together on problems of quantum computing since 1996. Gershenfeld first studied physics at Swarthmore College and Bell Laboratories. He went on to graduate school at Cornell University, where he obtained a doctorate in applied physics in 1990. Now a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Gershenfeld also serves as director of the physics and media group of the institute’s renowned Media Lab. Chuang studied at M.I.T. and at Stanford University, where he obtained a Ph.D. in 1997. He now studies quantum computation as a research staff member at the IBM Almaden Research Center in San Jose, Calif.