Sociocultural evolution, sociocultural evolutionism or cultural evolution are theories of cultural and social evolution that describe how cultures and societies change over time. Whereas sociocultural development traces processes that tend to increase the complexity of a society or culture, sociocultural evolution also considers process that can lead to decreases in complexity (degeneration) or that can produce variation or proliferation without any seemingly significant changes in complexity (cladogenesis). Sociocultural evolution is "the process by which structural reorganization is affected through time, eventually producing a form or structure which is qualitatively different from the ancestral form".

Most 19th-century and some 20th-century approaches to socioculture aimed to provide models for the evolution of humankind as a whole, arguing that different societies have reached different stages of social development. The most comprehensive attempt to develop a general theory of social evolution centering on the development of sociocultural systems, the work of Talcott Parsons (1902–1979), operated on a scale which included a theory of world history. Another attempt, on a less systematic scale, originated with the world-systems approach from the 1970s.

More recent approaches focus on changes specific to individual societies and reject the idea that cultures differ primarily according to how far each one is on some linear scale of social progress. Most modern archaeologists and cultural anthropologists work within the frameworks of neoevolutionism, sociobiology, and modernization theory.

Many different societies have existed in the course of human history, with estimates as high as over one million separate societiey; however, as of 2013, the number of different societies had reduced to about two hundred.[3]

Introduction

Specific theories of social or cultural evolution often attempt to explain differences between coeval societies by positing that different societies have reached different stages of development. Although such theories typically provide models for understanding the relationship between technologies, social structure or the values of a society, they vary as to the extent to which they describe specific mechanisms of variation and change.

Early sociocultural evolution theories – the ideas of Auguste Comte (1798–1857), Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) and Lewis Henry Morgan (1818–1881) – developed simultaneously with, but independently of, Charles Darwin's works and were popular from the late 19th century to the end of World War I. These 19th-century unilineal evolution theories claimed that societies start out in a primitive state and gradually become more civilized over time; they equated the culture and technology of Western civilization with progress. Some forms of early sociocultural evolution theories (mainly unilineal ones) have led to much-criticised theories like social Darwinism and scientific racism, sometimes used in the past[by whom?] to justify existing policies of colonialism and slavery and to justify new policies such as eugenics.

Most 19th-century and some 20th-century approaches aimed to provide models for the evolution of humankind as a single entity. However, most 20th-century approaches, such as multilineal evolution, focused on changes specific to individual societies. Moreover, they rejected directional change (i.e. orthogenetic, teleological or progressive change). Most archaeologists work within the framework of multilineal evolution. Other contemporary approaches to social change include neoevolutionism, sociobiology, dual inheritance theory, modernisation theory and postindustrial theory.

In his seminal 1976 book The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins wrote that "there are some examples of cultural evolution in birds and monkeys, but ... it is our own species that really shows what cultural evolution can do".[4]

Stadial theory

Enlightenment and later thinkers often speculated that societies progressed through stages: in other words, they saw history as stadial. While expecting humankind to show increasing development, theorists looked for what determined the course of human history. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), for example, saw social development as an inevitable process.[citation needed] It was assumed that societies start out primitive, perhaps in a state of nature, and could progress toward something resembling industrial Europe.While earlier authors such as Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) had discussed how societies change through time, the Scottish Enlightenment of the 18th century proved key in the development of the idea of sociocultural evolution.[citation needed] In relation to Scotland's union with England in 1707, several[quantify] Scottish thinkers pondered the relationship between progress and the affluence brought about by increased trade with England. They understood the changes Scotland was undergoing as involving transition from an agricultural to a mercantile society. In "conjectural histories", authors such as Adam Ferguson (1723–1816), John Millar (1735–1801) and Adam Smith (1723–1790) argued that societies all pass through a series of four stages: hunting and gathering, pastoralism and nomadism, agriculture, and finally a stage of commerce.

Auguste Comte (1798–1857)

Philosophical concepts of progress, such as that of Hegel, developed as well during this period. In France, authors such as Claude Adrien Helvétius (1715–1771) and other philosophes were influenced by the Scottish tradition. Later thinkers such as Comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825) developed these ideas.[citation needed] Auguste Comte (1798–1857) in particular presented a coherent view of social progress and a new discipline to study it: sociology.

These developments took place in a context of wider processes. The first process was colonialism. Although imperial powers settled most differences of opinion with their colonial subjects through force, increased awareness of non-Western peoples raised new questions for European scholars about the nature of society and of culture. Similarly, effective colonial administration required some degree of understanding of other cultures. Emerging theories of sociocultural evolution allowed Europeans to organise their new knowledge in a way that reflected and justified their increasing political and economic domination of others: such systems saw colonised people as less evolved, and colonising people as more evolved. Modern civilization (understood as the Western civilization), appeared the result of steady progress from a state of barbarism, and such a notion was common to many thinkers of the Enlightenment, including Voltaire (1694–1778).

The second process was the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism, which together allowed and promoted continual revolutions in the means of production. Emerging theories of sociocultural evolution reflected a belief that the changes in Europe brought by the Industrial Revolution and capitalism were improvements. Industrialisation, combined with the intense political change brought about by the French Revolution of 1789 and the U.S. Constitution, which paved the way for the dominance of democracy, forced European thinkers to reconsider some of their assumptions about how society was organised.

Eventually, in the 19th century three major classical theories of social and historical change emerged:

- sociocultural evolutionism

- the social cycle theory

- the Marxist theory of historical materialism.

Sociocultural evolutionism and the idea of progress

While sociocultural evolutionists agree that an evolution-like process leads to social progress, classical social evolutionists have developed many different theories, known as theories of unilineal evolution. Sociocultural evolutionism became the prevailing theory of early sociocultural anthropology and social commentary, and is associated with scholars like Auguste Comte, Edward Burnett Tylor, Lewis Henry Morgan, Benjamin Kidd, L. T. Hobhouse and Herbert Spencer. Sociocultural evolutionism attempted to formalise social thinking along scientific lines, with the added influence from the biological theory of evolution. If organisms could develop over time according to discernible, deterministic laws, then it seemed reasonable that societies could as well. Human society was compared to a biological organism, and social science equivalents of concepts like variation, natural selection, and inheritance were introduced as factors resulting in the progress of societies. The idea of progress led to that of a fixed "stages" through which human societies progress, usually numbering three – savagery, barbarism, and civilization – but sometimes many more. As early as the late 18th century, the Marquis de Condorcet (1743–1794) listed ten stages, or "epochs", each advancing the rights of man and perfecting the human race. At that time, anthropology was rising as a new scientific discipline, separating from the traditional views of "primitive" cultures that was usually based on religious views.Classical social evolutionism is most closely associated with the 19th-century writings of Auguste Comte and of Herbert Spencer (coiner of the phrase "survival of the fittest").[6] In many ways, Spencer's theory of "cosmic evolution" has much more in common with the works of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Auguste Comte than with contemporary works of Charles Darwin. Spencer also developed and published his theories several years earlier than Darwin. In regard to social institutions, however, there is a good case that Spencer's writings might be classified as social evolutionism. Although he wrote that societies over time progressed – and that progress was accomplished through competition – he stressed that the individual rather than the collectivity is the unit of analysis that evolves; that, in other words, evolution takes place through natural selection and that it affects social as well as biological phenomenon. Nonetheless, the publication of Darwin's works[which?] proved a boon to the proponents of sociocultural evolution, who saw the ideas of biological evolution as an attractive explanation for many questions about the development of society.[7]

Both Spencer and Comte view society as a kind of organism subject to the process of growth—from simplicity to complexity, from chaos to order, from generalisation to specialisation, from flexibility to organisation. They agree that the process of societal growth can be divided into certain stages, have[clarification needed] their beginning and eventual end, and that this growth is in fact social progress: each newer, more-evolved society is "better". Thus progressivism became one of the basic ideas underlying the theory of sociocultural evolutionism.[6]

Auguste Comte, known as "the father of sociology", formulated the law of three stages: human development progresses from the theological stage, in which nature was mythically conceived and man sought the explanation of natural phenomena from supernatural beings; through a metaphysical stage in which nature was conceived of as a result of obscure forces and man sought the explanation of natural phenomena from them; until the final positive stage in which all abstract and obscure forces are discarded, and natural phenomena are explained by their constant relationship.[8] This progress is forced through the development of human mind, and through increasing application of thought, reasoning and logic to the understanding of the world.[9] Comte saw the science-valuing society as the highest, most developed type of human organization.[8]

Herbert Spencer, who argued against government intervention as he believed that society should evolve toward more individual freedom,[10] differentiated between two phases of development as regards societies' internal regulation:[8] the "military" and "industrial" societies.[8] The earlier (and more primitive) military society has the goal of conquest and defense, is centralised, economically self-sufficient, collectivistic, puts the good of a group over the good of an individual, uses compulsion, force and repression, and rewards loyalty, obedience and discipline.[8] The industrial society, in contrast, has a goal of production and trade, is decentralised, interconnected with other societies via economic relations, works through voluntary cooperation and individual self-restraint, treats the good of individual as of the highest value, regulates the social life via voluntary relations; and values initiative, independence and innovation.[8][11] The transition process from the military to industrial society is the outcome of steady evolutionary processes within the society.[8]

Regardless of how scholars of Spencer interpret his relation to Darwin, Spencer became an incredibly popular figure in the 1870s, particularly in the United States. Authors such as Edward L. Youmans, William Graham Sumner, John Fiske, John W. Burgess, Lester Frank Ward, Lewis H. Morgan (1818–1881) and other thinkers of the gilded age all developed theories of social evolutionism as a result of their exposure to Spencer as well as to Darwin.

In his 1877 classic Ancient Societies, Lewis H. Morgan, an anthropologist whose ideas have had much impact on sociology, differentiated between three eras: savagery, barbarism and civilization, which are divided by technological inventions, like fire, bow, pottery in the savage era, domestication of animals, agriculture, metalworking in the barbarian era and alphabet and writing in the civilization era.[12] Thus Morgan drew a link between social progress and technological progress. Morgan viewed technological progress as a force behind social progress, and held that any social change—in social institutions, organizations or ideologies—has its beginnings in technological change.[12][13] Morgan's theories were popularized by Friedrich Engels, who based his famous work The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State on them.[12] For Engels and other Marxists this theory was important, as it supported their conviction that materialistic factors—economic and technological—are decisive in shaping the fate of humanity.[12]

Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917), a pioneer of anthropology, focused on the evolution of culture worldwide, noting that culture is an important part of every society and that it is also subject to a process of evolution. He believed that societies were at different stages of cultural development and that the purpose of anthropology was to reconstruct the evolution of culture, from primitive beginnings to the modern state.

Anthropologists Sir E.B. Tylor in England and Lewis Henry Morgan in the United States worked with data from indigenous people, who (they claimed) represented earlier stages of cultural evolution that gave insight into the process and progression of evolution of culture. Morgan would later[when?] have a significant influence on Karl Marx and on Friedrich Engels, who developed a theory of sociocultural evolution in which the internal contradictions in society generated a series of escalating stages that ended in a socialist society (see Marxism). Tylor and Morgan elaborated the theory of unilinear evolution, specifying criteria for categorising cultures according to their standing within a fixed system of growth of humanity as a whole and examining the modes and mechanisms of this growth. Theirs was often a concern with culture in general, not with individual cultures.

Their analysis of cross-cultural data was based on three assumptions:

- contemporary societies may be classified and ranked as more "primitive" or more "civilized"

- there are a determinate number of stages between "primitive" and "civilized" (e.g. band, tribe, chiefdom, and state)

- all societies progress through these stages in the same sequence, but at different rates

Lester Frank Ward

Lester Frank Ward (1841–1913), sometimes referred to[by whom?] as the "father" of American sociology, rejected many of Spencer's theories regarding the evolution of societies. Ward, who was also a botanist and a paleontologist, believed that the law of evolution functioned much differently in human societies than it did in the plant and animal kingdoms, and theorized that the "law of nature" had been superseded by the "law of the mind".[14] He stressed that humans, driven by emotions, create goals for themselves and strive to realize them (most effectively with the modern scientific method) whereas there is no such intelligence and awareness guiding the non-human world.[15] Plants and animals adapt to nature; man shapes nature. While Spencer believed that competition and "survival of the fittest" benefited human society and sociocultural evolution, Ward regarded competition as a destructive force, pointing out that all human institutions, traditions and laws were tools invented by the mind of man and that that mind designed them, like all tools, to "meet and checkmate" the unrestrained competition of natural forces.[14] Ward agreed with Spencer that authoritarian governments repress the talents of the individual, but he believed that modern democratic societies, which minimized the role of religion and maximized that of science, could effectively support the individual in his or her attempt to fully utilize their talents and achieve happiness. He believed that the evolutionary processes have four stages:

- First comes cosmogenesis, creation and evolution of the world.

- Then, when life arises, there is biogenesis.[15]

- Development of humanity leads to anthropogenesis, which is influenced by the human mind.[15]

- Finally there arrives sociogenesis, which is the science of shaping the evolutionary process itself to optimize progress, human happiness and individual self-actualization.[15]

Émile Durkheim, another of the "fathers" of sociology, developed a dichotomal view of social progress.[18] His key concept was social solidarity, as he defined social evolution in terms of progressing from mechanical solidarity to organic solidarity.[18] In mechanical solidarity, people are self-sufficient, there is little integration and thus there is the need for the use of force and repression to keep society together.[18] In organic solidarity, people are much more integrated and interdependent and specialisation and cooperation are extensive.[18] Progress from mechanical to organic solidarity is based firstly on population growth and increasing population density, secondly on increasing "morality density" (development of more complex social interactions) and thirdly on increasing specialisation in the workplace.[18] To Durkheim, the most important factor in social progress is the division of labour.[18] This[clarification needed] was later used in the mid-1900s by the economist Ester Boserup (1910–1999) to attempt to discount some aspects of Malthusian theory.

Ferdinand Tönnies (1855–1936) describes evolution as the development from informal society, where people have many liberties and there are few laws and obligations, to modern, formal rational society, dominated by traditions and laws, where people are restricted from acting as they wish.[19] He also notes that there is a tendency to standardisation and unification, when all smaller societies are absorbed into a single, large, modern society.[19] Thus Tönnies can be said to describe part of the process known today as globalization. Tönnies was also one of the first sociologists to claim that the evolution of society is not necessarily going in the right direction, that social progress is not perfect, and it can even be called a regression as the newer, more evolved societies are obtained only after paying a high cost, resulting in decreasing satisfaction of the individuals making up that society.[19] Tönnies' work became the foundation of neoevolutionism.[19]

Although Max Weber is not usually counted[by whom?] as a sociocultural evolutionist, his theory of tripartite classification of authority can be viewed[by whom?] as an evolutionary theory as well. Weber distinguishes three ideal types of political leadership, domination and authority:

- charismatic domination

- traditional domination (patriarchs, patrimonalism, feudalism)

- legal (rational) domination (modern law and state, bureaucracy)

Critique and impact on modern theories

The early 20th-century inaugurated a period of systematic critical examination, and rejection of the sweeping generalisations of the unilineal theories of sociocultural evolution. Cultural anthropologists such as Franz Boas (1858–1942), along with his students, including Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead, are regarded[by whom?] as the leaders of anthropology's rejection of classical social evolutionism.They used sophisticated ethnography and more rigorous empirical methods to argue that Spencer, Tylor, and Morgan's theories were speculative and systematically misrepresented ethnographic data. Theories regarding "stages" of evolution were especially criticised as illusions. Additionally, they rejected the distinction between "primitive" and "civilized" (or "modern"), pointing out that so-called primitive contemporary societies have just as much history, and were just as evolved, as so-called civilized societies. They therefore argued that any attempt to use this theory to reconstruct the histories of non-literate (i.e. leaving no historical documents) peoples is entirely speculative and unscientific.

They observed that the postulated progression, which typically ended with a stage of civilization identical to that of modern Europe, is ethnocentric. They also pointed out that the theory assumes that societies are clearly bounded and distinct, when in fact cultural traits and forms often cross social boundaries and diffuse among many different societies (and are thus an important mechanism of change). Boas in his culture-history approach focused on anthropological fieldwork in an attempt to identify factual processes instead of what he criticized as speculative stages of growth. His approach greatly influenced American anthropology in the first half of the 20th century, and marked a retreat from high-level generalization and from "systems building".

Later critics observed that the assumption of firmly bounded societies was proposed precisely at the time when European powers were colonising non-Western societies, and was thus self-serving. Many anthropologists and social theorists now consider unilineal cultural and social evolution a Western myth seldom based on solid empirical grounds. Critical theorists argue that notions of social evolution are simply justifications for power by the élites of society. Finally, the devastating World Wars that occurred between 1914 and 1945 crippled Europe's self-confidence. After millions of deaths, genocide, and the destruction of Europe's industrial infrastructure, the idea of progress seemed dubious at best.

Thus modern sociocultural evolutionism rejects most of classical social evolutionism due to various theoretical problems:

- The theory was deeply ethnocentric—it makes heavy value judgments about different societies, with Western civilization seen as the most valuable.

- It assumed all cultures follow the same path or progression and have the same goals.

- It equated civilization with material culture (technology, cities, etc.)

Max Weber, disenchantment, and critical theory

Max Weber in 1917

Weber's major works in economic sociology and the sociology of religion dealt with the rationalization, secularisation, and so called "disenchantment" which he associated with the rise of capitalism and modernity.[20] In sociology, rationalization is the process whereby an increasing number of social actions become based on considerations of teleological efficiency or calculation rather than on motivations derived from morality, emotion, custom, or tradition. Rather than referring to what is genuinely "rational" or "logical", rationalization refers to a relentless quest for goals that might actually function to the detriment of a society. Rationalization is an ambivalent aspect of modernity, manifested especially in Western society - as a behaviour of the capitalist market, of rational administration in the state and bureaucracy, of the extension of modern science, and of the expansion of modern technology.[citation needed]

Weber's thought regarding the rationalizing and secularizing tendencies of modern Western society (sometimes described as the "Weber Thesis") would blend with Marxism to facilitate critical theory, particularly in the work of thinkers such as Jürgen Habermas (born 1929). Critical theorists, as antipositivists, are critical of the idea of a hierarchy of sciences or societies, particularly with respect to the sociological positivism originally set forth by Comte. Jürgen Habermas has critiqued the concept of pure instrumental rationality as meaning that scientific-thinking becomes something akin to ideology itself. For theorists such as Zygmunt Bauman (1925-2017), rationalization as a manifestation of modernity may be most closely and regrettably associated with the events of the Holocaust.

Modern theories

When the critique of classical social evolutionism became widely accepted, modern anthropological and sociological approaches changed respectively. Modern theories are careful to avoid unsourced, ethnocentric speculation, comparisons, or value judgments; more or less regarding individual societies as existing within their own historical contexts. These conditions provided the context for new theories such as cultural relativism and multilineal evolution.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Gordon Childe revolutionized the study of cultural evolutionism. He conducted a comprehensive pre-history account that provided scholars with evidence for African and Asian cultural transmission into Europe. He combated scientific racism by finding the tools and artifacts of the indigenous people from Africa and Asia and showed how they influenced the technology of European culture. Evidence from his excavations countered the idea of Aryan supremacy and superiority. Childe explained cultural evolution by his theory of divergence with modifications of convergence. He postulated that different cultures form separate methods that meet different needs, but when two cultures were in contact they developed similar adaptations, solving similar problems. Rejecting Spencer’s theory of parallel cultural evolution, Childe found that interactions between cultures contributed to the convergence of similar aspects most often attributed to one culture. Childe placed emphasis on human culture as a social construct rather than products of environmental or technological contexts. Childe coined the terms "Neolithic Revolution", and "Urban Revolution" which are still used today in the branch of pre-historic anthropology.

In 1941 anthropologist Robert Redfield wrote about a shift from ‘folk society’ to ‘urban society’. By the 1940s cultural anthropologists such as Leslie White and Julian Steward sought to revive an evolutionary model on a more scientific basis, and succeeded in establishing an approach known as neoevolutionism. White rejected the opposition between "primitive" and "modern" societies but did argue that societies could be distinguished based on the amount of energy they harnessed, and that increased energy allowed for greater social differentiation (White’s law). Steward on the other hand rejected the 19th-century notion of progress, and instead called attention to the Darwinian notion of "adaptation", arguing that all societies had to adapt to their environment in some way.

The anthropologists Marshall Sahlins and Elman Service prepared an edited volume, Evolution and Culture, in which they attempted to synthesise White’s and Steward’s approaches.[21] Other anthropologists, building on or responding to work by White and Steward, developed theories of cultural ecology and ecological anthropology. The most prominent examples are Peter Vayda and Roy Rappaport. By the late 1950s, students of Steward such as Eric Wolf and Sidney Mintz turned away from cultural ecology to Marxism, World Systems Theory, Dependency theory and Marvin Harris’s Cultural materialism.

Today most anthropologists reject 19th-century notions of progress and the three assumptions of unilineal evolution. Following Steward, they take seriously the relationship between a culture and its environment to explain different aspects of a culture. But most modern cultural anthropologists have adopted a general systems approach, examining cultures as emergent systems and arguing that one must consider the whole social environment, which includes political and economic relations among cultures. As a result of simplistic notions of "progressive evolution", more modern, complex cultural evolution theories (such as Dual Inheritance Theory, discussed below) receive little attention in the social sciences, having given way in some cases to a series of more humanist approaches. Some reject the entirety of evolutionary thinking and look instead at historical contingencies, contacts with other cultures, and the operation of cultural symbol systems. In the area of development studies, authors such as Amartya Sen have developed an understanding of ‘development’ and ‘human flourishing’ that also question more simplistic notions of progress, while retaining much of their original inspiration.

Neoevolutionism

Neoevolutionism was the first in a series of modern multilineal evolution theories. It emerged in the 1930s and extensively developed in the period following the Second World War and was incorporated into both anthropology and sociology in the 1960s. It bases its theories on empirical evidence from areas of archaeology, palaeontology, and historiography and tries to eliminate any references to systems of values, be it moral or cultural, instead trying to remain objective and simply descriptive.[22]While 19th-century evolutionism explained how culture develops by giving general principles of its evolutionary process, it was dismissed by the Historical Particularists as unscientific in the early 20th century. It was the neo-evolutionary thinkers who brought back evolutionary thought and developed it to be acceptable to contemporary anthropology.

Neo-evolutionism discards many ideas of classical social evolutionism, namely that of social progress, so dominant in previous sociology evolution-related theories.[22] Then neo-evolutionism discards the determinism argument and introduces probability, arguing that accidents and free will greatly affect the process of social evolution.[22] It also supports counterfactual history—asking "what if" and considering different possible paths that social evolution may take or might have taken, and thus allows for the fact that various cultures may develop in different ways, some skipping entire stages others have passed through.[22] Neo-evolutionism stresses the importance of empirical evidence. While 19th-century evolutionism used value judgments and assumptions for interpreting data, neo-evolutionism relies on measurable information for analysing the process of sociocultural evolution.

Leslie White, author of The Evolution of Culture: The Development of Civilization to the Fall of Rome (1959), attempted to create a theory explaining the entire history of humanity.[22] The most important factor in his theory is technology.[22] Social systems are determined by technological systems, wrote White in his book,[23] echoing the earlier theory of Lewis Henry Morgan. He proposes a society’s energy consumption as a measure of its advancement.[22] He differentiates between five stages of human development.[22] In the first, people use the energy of their own muscles.[22] In the second, they use the energy of domesticated animals.[22] In the third, they use the energy of plants (so White refers to agricultural revolution here).[22] In the fourth, they learn to use the energy of natural resources: coal, oil, gas.[22] In the fifth, they harness nuclear energy.[22] White introduced a formula, P=E*T, where E is a measure of energy consumed, and T is the measure of efficiency of technical factors utilising the energy.[22] This theory is similar to Russian astronomer Nikolai Kardashev’s later theory of the Kardashev scale.

Julian Steward, author of Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution (1955, reprinted 1979), created the theory of "multilinear" evolution which examined the way in which societies adapted to their environment. This approach was more nuanced than White’s theory of "unilinear evolution." Steward rejected the 19th-century notion of progress, and instead called attention to the Darwinian notion of "adaptation", arguing that all societies had to adapt to their environment in some way. He argued that different adaptations could be studied through the examination of the specific resources a society exploited, the technology the society relied on to exploit these resources, and the organization of human labour. He further argued that different environments and technologies would require different kinds of adaptations, and that as the resource base or technology changed, so too would a culture. In other words, cultures do not change according to some inner logic, but rather in terms of a changing relationship with a changing environment. Cultures therefore would not pass through the same stages in the same order as they changed—rather, they would change in varying ways and directions. He called his theory "multilineal evolution". He questioned the possibility of creating a social theory encompassing the entire evolution of humanity; however, he argued that anthropologists are not limited to describing specific existing cultures. He believed that it is possible to create theories analysing typical common culture, representative of specific eras or regions. As the decisive factors determining the development of given culture he pointed to technology and economics, but noted that there are secondary factors, like political system, ideologies and religion. All those factors push the evolution of a given society in several directions at the same time; hence the application of the term "multilinear" to his theory of evolution.

Marshall Sahlins, co-editor with Elman Service of Evolution and Culture (1960), divided the evolution of societies into ‘general’ and ‘specific’.[24] General evolution is the tendency of cultural and social systems to increase in complexity, organization and adaptiveness to environment.[24] However, as the various cultures are not isolated, there is interaction and a diffusion of their qualities (like technological inventions).[24] This leads cultures to develop in different ways (specific evolution), as various elements are introduced to them in different combinations and at different stages of evolution.[24]

In his Power and Prestige (1966) and Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology (1974), Gerhard Lenski expands on the works of Leslie White and Lewis Henry Morgan,[24] developing the ecological-evolutionary theory. He views technological progress as the most basic factor in the evolution of societies and cultures.[24] Unlike White, who defined technology as the ability to create and utilise energy, Lenski focuses on information—its amount and uses.[24] The more information and knowledge (especially allowing the shaping of natural environment) a given society has, the more advanced it is.[24] He distinguishes four stages of human development, based on advances in the history of communication.[24] In the first stage, information is passed by genes.[24] In the second, when humans gain sentience, they can learn and pass information through by experience.[24] In the third, humans start using signs and develop logic.[24] In the fourth, they can create symbols and develop language and writing.[24] Advancements in the technology of communication translate into advancements in the economic system and political system, distribution of goods, social inequality and other spheres of social life. He also differentiates societies based on their level of technology, communication and economy: (1) hunters and gatherers, (2) agricultural, (3) industrial, and (4) special (like fishing societies).[24]

Talcott Parsons, author of Societies: Evolutionary and Comparative Perspectives (1966) and The System of Modern Societies (1971) divided evolution into four subprocesses: (1) division, which creates functional subsystems from the main system; (2) adaptation, where those systems evolve into more efficient versions; (3) inclusion of elements previously excluded from the given systems; and (4) generalization of values, increasing the legitimization of the ever more complex system.[25] He shows those processes on 4 stages of evolution: (I) primitive or foraging, (II) archaic agricultural, (III) classical or "historic" in his terminology, using formalized and universalizing theories about reality and (IV) modern empirical cultures. However, these divisions in Parsons’ theory are the more formal ways in which the evolutionary process is conceptualized, and should not be mistaken for Parsons’ actual theory. Parsons develops a theory where he tries to reveal the complexity of the processes which take form between two points of necessity, the first being the cultural "necessity," which is given through the values-system of each evolving community; the other is the environmental necessities, which most directly is reflected in the material realities of the basic production system and in the relative capacity of each industrial-economical level at each window of time. Generally, Parsons highlights that the dynamics and directions of these processes is shaped by the cultural imperative embodied in the cultural heritage, and more secondarily, an outcome of sheer "economic" conditions.

Michel Foucault’s recent, and very much misunderstood, concepts such as Biopower, Biopolitics and Power-knowledge has been cited as breaking free from the traditional conception of man as cultural animal. Foucault regards both the terms “cultural animal” and "human nature"as misleading abstractions, leading to a non critical exemption of man and anything can be justified when regarding social processes or natural phenomena (social phenomena).[26] Foucault argues these complex processes are interrelated, and difficult to study for a reason so those 'truths' cannot be topled or disrupted. For Foucault, the many modern concepts and practices that attempt to uncover “the truth” about human beings (either psychologically, sexually, religion or spiritually) actually create the very types of people they purport to discover. Requiring trained "specialists" and knowledge codes and know how, rigorous pursuit is "put off" or delayed which makes any kind of study not only a ‘taboo’ subject but deliberately ignored. He cites the concept of ‘truth’[27] within many human cultures and the ever flowing dynamics between truth, power, and knowledge as a resultant complex dynamics (Foucault uses the term regimes of truth) and how they flow with ease like water which make the concept of ‘truth’ impervious to any further rational investigation. Some of the West’s most powerful social institutions are powerful for a reason, not because they exhibit powerful structures which inhibit investigation or it is illegal to investigate there historical foundation. It is the very notion of "legitimacy" Foucault cites as examples of "truth" which function as a "Foundationalism" claims to historical accuracy. Foucault argues, systems such as Medicine, Prisons,[28][29] and Religion, as well as groundbreaking works on more abstract theoretical issues of power are suspended or buried into oblivion.[30] He cites as further examples the ‘Scientific study’ of Population biology and Population genetics[31] as both examples of this kind of “Biopower” over the vast majority of the human population giving the new founded political population their ‘politics’ or polity. With the advent of biology and genetics teamed together as new scientific innovations notions of study of knowledge regarding truth belong to the realm of experts who will never divulge their secrets openly, while the bulk of the population do not know their own biology or genetics this is done for them by the experts. This functions as a truth ignorance mechanism: “where the “subjugated knowledge’s,” as those that have been both written out of history and submerged in it in a masked form produces what we now know as truth. He calls them “Knowledge’s from below” and a “historical knowledge of struggles”.Genealogy, Foucault suggests, is a way of getting at these knowledge’s and struggles; “they are about the insurrection of knowledge’s.”Foucault tries to show with the added dimension of “Milieu”(derived from Newtonian mechanics) how this Milieu from the 17th century with the development of the Biological and Physical sciences managed to be interwoven into the political, social and biological relationship of men with the arrival of the concept Work placed upon the industrial population.[32] Foucault uses the term borrowed from Jakob von Uexküll Umwelt meaning environment within. Technology, production, Cartography the production of Nation states and Government making the efficiency of the Body politic, Law, Heredity and Consanguine[33] not only sound genuine and beyond historical origin and foundation it can be turned into ‘exact truth’ where the individual and the societal body are not only subjugated and nullified but dependent upon it. Foucault is not denying that genetic or biological study is inaccurate or is simply not telling the truth what he means is that notions of this newly discovered sciences were extended to include the vast majority (or whole populations) of populations as an exercise in “regimes change”.Foucault argues that the conceptual meaning from the Middle ages and Canon law period, the Geocentric model, later superseded by the Heliocentrism model placing the position of the law of right in the Middle ages (Exclusive right or its correct legal term Sui generis) was the Divine right of kings and Absolute monarchy where the previous incarnation of truth and rule of political sovereignty was considered absolute and unquestioned by Political Philosophy(monarchs, popes and emperors). However, Foucault notices that this Pharaonic version of Political power was transversed and it was with 18th-century emergence of Capitalism and Liberal democracy that these terms began to be “democratized”.The modern Pharaonic version represented by the President, the monarch, the Pope and the Prime minister all became propagandized versions or examples of symbol agents all aimed at towards a newly discovered phenomenon, the population.[34][32] As symbolic symbol agents of power making the mass population having to sacrifice itself all in the name of the newly formed voting franchise we now call Democracy. However, this was all turned on its head (when the Medieval rulers were thrown out and replaced by a more exact apparatus now called the state) when the human sciences suddenly discovered: “The set of mechanisms through which the basic biological features of the human species became an object of a political strategy and took on board the fundamental facts that humans were now a biological species."[35][36]

Sociobiology

Sociobiology departs perhaps the furthest from classical social evolutionism.[37] It was introduced by Edward Wilson in his 1975 book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis and followed his adaptation of evolutionary theory to the field of social sciences. Wilson pioneered the attempt to explain the evolutionary mechanics behind social behaviours such as altruism, aggression, and nurturance.[37] In doing so, Wilson sparked one of the greatest scientific controversies of the 20th century.[37]The current theory of evolution, the modern evolutionary synthesis (or neo-darwinism), explains that evolution of species occurs through a combination of Darwin’s mechanism of natural selection and Gregor Mendel’s theory of genetics as the basis for biological inheritance and mathematical population genetics.[37] Essentially, the modern synthesis introduced the connection between two important discoveries; the units of evolution (genes) with the main mechanism of evolution (selection).[37]

Due to its close reliance on biology, sociobiology is often considered a branch of the biology, although it uses techniques from a plethora of sciences, including ethology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, population genetics, and many others. Within the study of human societies, sociobiology is closely related to the fields of human behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology.

Sociobiology has remained highly controversial as it contends genes explain specific human behaviours, although sociobiologists describe this role as a very complex and often unpredictable interaction between nature and nurture. The most notable critics of the view that genes play a direct role in human behaviour have been biologists Richard Lewontin Steven Rose and Stephen Jay Gould.

Since the rise of evolutionary psychology, another school of thought, Dual Inheritance Theory, has emerged in the past 25 years that applies the mathematical standards of Population genetics to modeling the adaptive and selective principles of culture. This school of thought was pioneered by Robert Boyd at UCLA and Peter Richerson at UC Davis and expanded by William Wimsatt, among others. Boyd and Richerson’s book, Culture and the Evolutionary Process (1985),[38] was a highly mathematical description of cultural change, later published in a more accessible form in Not by Genes Alone (2004).[39] In Boyd and Richerson’s view, cultural evolution, operating on socially learned information, exists on a separate but co-evolutionary track from genetic evolution, and while the two are related, cultural evolution is more dynamic, rapid, and influential on human society than genetic evolution. Dual Inheritance Theory has the benefit of providing unifying territory for a "nature and nurture" paradigm and accounts for more accurate phenomenon in evolutionary theory applied to culture, such as randomness effects (drift), concentration dependency, "fidelity" of evolving information systems, and lateral transmission through communication.[40]

Theory of modernization

Theories of modernization have been developed and popularized in 1950s and 1960s and are closely related to the dependency theory and development theory.[41] They combine the previous theories of sociocultural evolution with practical experiences and empirical research, especially those from the era of decolonization. The theory states that:- Western countries are the most developed, and the rest of the world (mostly former colonies) is in the earlier stages of development, and will eventually reach the same level as the Western world.[41]

- Development stages go from the traditional societies to developed ones.[41]

- Third World countries have fallen behind with their social progress and need to be directed on their way to becoming more advanced.[41]

Among the scientists who contributed much to this theory are Walt Rostow, who in his The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (1960) concentrates on the economic system side of the modernization, trying to show factors needed for a country to reach the path to modernization in his Rostovian take-off model.[41] David Apter concentrated on the political system and history of democracy, researching the connection between democracy, good governance and efficiency and modernization.[41] David McClelland (The Achieving Society, 1967) approached this subject from the psychological perspective, with his motivations theory, arguing that modernization cannot happen until given society values innovation, success and free enterprise.[41] Alex Inkeles (Becoming Modern, 1974) similarly creates a model of modern personality, which needs to be independent, active, interested in public policies and cultural matters, open to new experiences, rational and able to create long-term plans for the future.[41] Some works of Jürgen Habermas are also connected with this subfield.

The theory of modernization has been subject to some criticism similar to that levied against classical social evolutionism, especially for being too ethnocentric, one-sided and focused on the Western world and its culture.

Prediction for a stable cultural and social future

Cultural evolution follows punctuated equilibrium which Gould and Eldredge developed for biological evolution. Bloomfield[42][43] has written that human societies follow punctuated equilibrium which would mean first, a stable society, and then a transition resulting in a subsequent stable society with greater complexity. This model would claim mankind has had a stable animal society, a transition to a stable tribal society, another transition to a stable peasant society and is currently in a transitional industrial society.The status of a human society rests on the productivity of food production. Deevey[44] reported on the growth of the number of humans. Deevey also reported on the productivity of food production, noting that productivity changes very little for stable societies, but increases during transitions. When productivity and especially food productivity can no longer be increased, Bloomfield has proposed that man will have achieved a stable automated society.[45] Space is also assumed to allow for the continued growth of the human population, as well as providing a solution to the current pollution problem by providing limitless energy from solar satellite power stations.

Contemporary perspectives

Political perspectives

The Cold War period was marked by rivalry between two superpowers, both of which considered themselves to be the most highly evolved cultures on the planet. The USSR painted itself as a socialist society which emerged from class struggle, destined to reach the state of communism, while sociologists in the United States (such as Talcott Parsons) argued that the freedom and prosperity of the United States were a proof of a higher level of sociocultural evolution of its culture and society. At the same time, decolonization created newly independent countries who sought to become more developed—a model of progress and industrialization which was itself a form of sociocultural evolution.There is, however, a tradition in European social theory from Rousseau to Max Weber arguing that this progression coincides with a loss of human freedom and dignity. At the height of the Cold War, this tradition merged with an interest in ecology to influence an activist culture in the 1960s. This movement produced a variety of political and philosophical programs which emphasized the importance of bringing society and the environment into harmony.

Technological perspectives

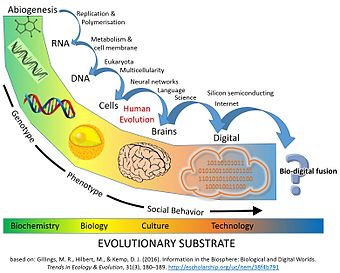

Schematic Timeline of Information and Replicators in the Biosphere: major evolutionary transitions in information processing[46]

Many[who?] argue that the next stage of sociocultural evolution consists of a merger with technology, especially information processing technology. Several cumulative major transitions of evolution have transformed life through key innovations in information storage and replication, including RNA, DNA, multicellularity, and also language and culture as inter-human information processing systems.[47][48] in this sense it can be argued that the carbon-based biosphere has generated a cognitive system (humans) capable of creating technology that will result in a comparable evolutionary transition. "Digital information has reached a similar magnitude to information in the biosphere. It increases exponentially, exhibits high-fidelity replication, evolves through differential fitness, is expressed through artificial intelligence (AI), and has facility for virtually limitless recombination. Like previous evolutionary transitions, the potential symbiosis between biological and digital information will reach a critical point where these codes could compete via natural selection. Alternatively, this fusion could create a higher-level superorganism employing a low-conflict division of labor in performing informational tasks...humans already embrace fusions of biology and technology. We spend most of our waking time communicating through digitally mediated channels, ...most transactions on the stock market are executed by automated trading algorithms, and our electric grids are in the hands of artificial intelligence. With one in three marriages in America beginning online, digital algorithms are also taking a role in human pair bonding and reproduction".[46]

Anthropological perspectives

Current political theories of the new tribalists consciously mimic ecology and the life-ways of indigenous peoples, augmenting them with modern sciences. Ecoregional Democracy attempts to confine the "shifting groups", or tribes, within "more or less clear boundaries" that a society inherits from the surrounding ecology, to the borders of a naturally occurring ecoregion. Progress can proceed by competition between but not within tribes, and it is limited by ecological borders or by Natural Capitalism incentives which attempt to mimic the pressure of natural selection on a human society by forcing it to adapt consciously to scarce energy or materials. Gaians argue that societies evolve deterministically to play a role in the ecology of their biosphere, or else die off as failures due to competition from more efficient societies exploiting nature's leverage.Thus, some have appealed to theories of sociocultural evolution to assert that optimizing the ecology and the social harmony of closely knit groups is more desirable or necessary than the progression to "civilization." A 2002 poll of experts on Neoarctic and Neotropic indigenous peoples (reported in Harper's magazine)[citation needed] revealed that all of them would have preferred to be a typical New World person in the year 1491, prior to any European contact, rather than a typical European of that time. This approach has been criticised by pointing out that there are a number of historical examples of indigenous peoples doing severe environmental damage (such as the deforestation of Easter Island and the extinction of mammoths in North America) and that proponents of the goal have been trapped by the European stereotype of the noble savage.