Average tariff rates for selected countries (1913–2007)

Tariff rates in Japan (1870–1960)

Average tariff rates in Spain and Italy (1860–1910)

Average tariff rates (France, UK, US)

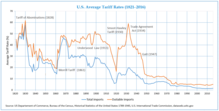

Average tariff rates in US (1821–2016)

US Trade Balance and Trade Policy (1895–2015)

Average tariff rates on manufactured products

Average Levels of Duties (1875 and 1913)

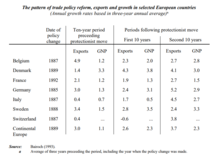

Trade Policy, Exports and Growth in European Countries

History

Tariffs in United States history

According to Michael Lind, protectionism was America's de facto policy from the passage of the Tariff of 1816 to World War II, "switching to free trade only in 1945, when most of its industrial competitors had been wiped out" by the war.[1] It has been argued that one of the underlying motivations for the American Revolution itself was a desire to industrialize, and reverse the trade deficit with Britain, which had grown by a factor of ten in the space of a few decades, from £67,000 (1721–30) to £739,000 (1761–70).[2]Paul Bairoch states that since the end of the 18th century, the United States has been "the homeland and bastion of modern protectionism". In fact, the United States never adhered to free trade until 1945. A protectionist policy was adopted during the presidency of George Washington by Alexander Hamilton, the first US Treasury Secretary. Hamilton wrote the Report on Manufactures, which called for customs barriers to allow American industrial development and to help protect infant industries, including bounties (subsidies) derived in part from those tariffs. This text was one of the references of the German economist Friedrich List (1789–1846). This policy remained throughout the 19th century and the overall level of tariffs was very high (close to 50% in 1830). The victory of the protectionist states of the North over the free trade southern states at the end of the Civil War (1861–1865) perpetuated this trend, even during periods of free trade in Europe (1860–1880).[3]

Hamilton explained that despite an initial “increase of price” caused by regulations that control foreign competition, once a “domestic manufacture has attained to perfection… it invariably becomes cheaper.” George Washington signed the Tariff Act of 1789, making it the Republic's second ever piece of legislation. Increasing the domestic supply of manufactured goods, particularly war materials, was seen as an issue of national security. Washington and Hamilton believed that political independence was predicated upon economic independence.[4]

In the 19th century, statesmen such as Senator Henry Clay continued Hamilton's themes within the Whig Party under the name "American System." The fledgling Republican Party led by Abraham Lincoln, who called himself a "Henry Clay tariff Whig", strongly opposed free trade, and implemented a 44-percent tariff during the Civil War—in part to pay for railroad subsidies and for the war effort, and to protect favored industries.[5]

From 1871 to 1913, “the average U.S. tariff on dutiable imports never fell below 38 percent [and] gross national product (GNP) grew 4.3 percent annually, twice the pace in free trade Britain and well above the U.S. average in the 20th century,” notes Alfred Eckes Jr., chairman of the U.S. International Trade Commission under President Reagan.

In 1896, the GOP platform pledged to “renew and emphasize our allegiance to the policy of protection, as the bulwark of American industrial independence, and the foundation of development and prosperity. This true American policy taxes foreign products and encourages home industry. It puts the burden of revenue on foreign goods; it secures the American market for the American producer. It upholds the American standard of wages for the American workingman.”

Tariff and the Great Depression

Most economists hold the opinion that the tariff act did not greatly worsen the great depression:Milton Friedman held the opinion that the Smoot–Hawley tariff of 1930 did not cause the Great Depression, instead he blamed the lack of sufficient action on the part of the Federal Reserve. Douglas A. Irwin wrote: "most economists, both liberal and conservative, doubt that Smoot–Hawley played much of a role in the subsequent contraction."[6].

Peter Temin, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, explained that a tariff is an expansionary policy, like a devaluation as it diverts demand from foreign to home producers. He noted that exports were 7 percent of GNP in 1929, they fell by 1.5 percent of 1929 GNP in the next two years and the fall was offset by the increase in domestic demand from tariff. He concluded that contrary the popular argument, contractionary effect of the tariff was small.[7]

William Bernstein wrote "most economic historians now believe that only a minuscule part of that huge loss of both world GDP and the United States' GDP can be ascribed to the tariff wars "because trade was only nine percent of global output, not enough to account for the seventeen percent drop in GDP following the Crash. He thinks the damage done could not possibly have exceeded 2 percent of world GDP and tariff "didn't even significantly deepen the Great Depression." (A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World)

Nobel laureate Maurice Allais maintained that tariff was rather helpful in the face of deregulation of competition in the global labor market and excessively loose credit prior to the Crash which, according to him, caused the crisis in financial and banking sectors. He noted higher trade barriers were partly a means to protect domestic demand from deflation and external disturbances. He observes domestic production in the major industrialized countries fell faster than international trade contracted; if contraction of foreign trade had been the cause of the Depression, he argues, the opposite should have occurred. So, the decline in trade between 1929 and 1933 was a consequence of the Depression, not a cause. Most of the trade contraction took place between January 1930 and July 1932, before the introduction of the majority of protectionist measures, excepting limited American measures applied in the summer of 1930. It was the collapse of international liquidity that caused of the contraction of trade.[8]

Etymology

The small Spanish town of Tarifa is sometimes credited with being the origin of the word "tariff", since it was the first port in history to charge merchants for the use of its docks.[9] The name "Tarifa" itself is derived from the name of the Berber warrior, Tarif ibn Malik. However, other sources assume that the origin of tariff is the Italian word tariffa translated as "list of prices, book of rates", which is derived from the Arabic ta'rif meaning "making known" or "to define".[10]Customs duty

A customs duty or due is the indirect tax levied on the import or export of goods in international trade. In economic sense, a duty is also a kind of consumption tax. A duty levied on goods being imported is referred to as an import duty. Similarly, a duty levied on exports is called an export duty. A tariff, which is actually a list of commodities along with the leviable rate (amount) of customs duty, is popularly referred to as a customs duty.Calculation of customs duty

Customs duty is calculated on the determination of the assessable value in case of those items for which the duty is levied ad valorem. This is often the transaction value unless a customs officer determines assessable value in accordance with the Harmonized System. For certain items like petroleum and alcohol, customs duty is realized at a specific rate applied to the volume of the import or export consignments.Harmonized System of Nomenclature

For the purpose of assessment of customs duty, products are given an identification code that has come to be known as the Harmonized System code. This code was developed by the World Customs Organization based in Brussels. A Harmonized System code may be from four to ten digits. For example, 17.03 is the HS code for molasses from the extraction or refining of sugar. However, within 17.03, the number 17.03.90 stands for "Molasses (Excluding Cane Molasses)".Introduction of Harmonized System code in 1990s has largely replaced the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC), though SITC remains in use for statistical purposes. In drawing up the national tariff, the revenue departments often specifies the rate of customs duty with reference to the HS code of the product. In some countries and customs unions, 6-digit HS codes are locally extended to 8 digits or 10 digits for further tariff discrimination: for example the European Union uses its 8-digit CN (Combined Nomenclature) and 10-digit TARIC codes.

Customs authority

A Customs authority in each country is responsible for collecting taxes on the import into or export of goods out of the country. Normally the Customs authority, operating under national law, is authorized to examine cargo in order to ascertain actual description, specification volume or quantity, so that the assessable value and the rate of duty may be correctly determined and applied.Evasion

Evasion of customs duties takes place mainly in two ways. In one, the trader under-declares the value so that the assessable value is lower than actual. In a similar vein, a trader can evade customs duty by understatement of quantity or volume of the product of trade. A trader may also evade duty by misrepresenting traded goods, categorizing goods as items which attract lower customs duties. The evasion of customs duty may take place with or without the collaboration of customs officials. Evasion of customs duty does not necessarily constitute smuggling.[citation needed]Duty-free goods

Many countries allow a traveler to bring goods into the country duty-free. These goods may be bought at ports and airports or sometimes within one country without attracting the usual government taxes and then brought into another country duty-free. Some countries impose allowances which limit the number or value of duty-free items that one person can bring into the country. These restrictions often apply to tobacco, wine, spirits, cosmetics, gifts and souvenirs. Often foreign diplomats and UN officials are entitled to duty-free goods. Duty-free goods are imported and stocked in what is called a bonded warehouse.Duty calculation for companies in real life

With many methods and regulations, businesses at times struggle to manage the duties. In addition to difficulties in calculations, there are challenges in analyzing duties; and to opt for duty free options like using a bonded warehouse.Companies use ERP software to calculate duties automatically to, on one hand, avoid error-prone manual work on duty regulations and formulas and on the other hand, manage and analyze the historically paid duties. Moreover, ERP software offers an option for customs warehouse, introduced to save duty and VAT payments. In addition, the duty deferment and suspension is also taken into consideration.

Economic analysis

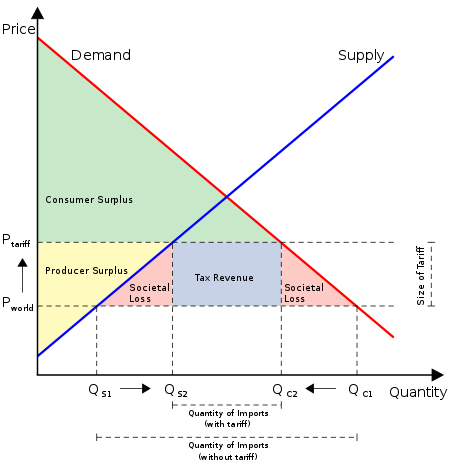

Neoclassical economic theorists tend to view tariffs as distortions to the free market. Typical analyses find that tariffs tend to benefit domestic producers and government at the expense of consumers, and that the net welfare effects of a tariff on the importing country are negative. Normative judgements often follow from these findings, namely that it may be disadvantageous for a country to artificially shield an industry from world markets and that it might be better to allow a collapse to take place. Opposition to all tariff aims to reduce tariffs and to avoid countries discriminating between differing countries when applying tariffs. The diagrams above show the costs and benefits of imposing a tariff on a good in the domestic economy.When incorporating free international trade into the model we use a supply curve denoted as

(diagram 1) or

(diagram 1) or  (diagram 2). This curve represents the assumption that the international supply of the good or service is perfectly elastic and that the world can produce at a near infinite quantity of the good. Before the tariff, there is a quantity demanded of Qc1 (diagram 1) or D (diagram 2). The difference between quantity demanded and quantity supplied (between D and S on diagram 2, respectively) was filled by importing from abroad. This is shown on diagram 1 as Quantity of Imports (without tariff).

After the imposition of a tariff, domestic price rises, but foreign export prices fall due to the difference in tax incidence on the consumers (at home) and producers (abroad).

(diagram 2). This curve represents the assumption that the international supply of the good or service is perfectly elastic and that the world can produce at a near infinite quantity of the good. Before the tariff, there is a quantity demanded of Qc1 (diagram 1) or D (diagram 2). The difference between quantity demanded and quantity supplied (between D and S on diagram 2, respectively) was filled by importing from abroad. This is shown on diagram 1 as Quantity of Imports (without tariff).

After the imposition of a tariff, domestic price rises, but foreign export prices fall due to the difference in tax incidence on the consumers (at home) and producers (abroad).

The new price level at Home is Ptariff or Pt, which is higher than the world price. More of the good is now produced at Home – it now makes Qs2 (diagram 1) or S* (diagram 2) of the good. Due to the higher price, only Qc2 or D* of the good is demanded by Home. The difference between the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded is still filled by importing from abroad. However, the imposition of the tariff reduces the quantity of imports from D − S to D* − S* (diagram 2). This is also shown in diagram 1 as Quantity of Imports (with tariff).

Domestic producers enjoy a gain in their surplus. Producer surplus, defined as the difference between what the producers were willing to receive by selling a good and the actual price of the good, expands from the region below Pw to the region below Pt. Therefore, the domestic producers gain an amount shown by the area A.

Domestic consumers face a higher price, reducing their welfare. Consumer surplus is the area between the price line and the demand curve. Therefore, the consumer surplus shrinks from the area above Pw to the area above Pt, i.e. it shrinks by the areas A, B, C and D. This includes the gained producer surplus, the deadweight loss, and the tax revenue.

The government gains from the taxes. It charges an amount Pt − Pt* of tariff for every good imported. Since D* − S* goods are imported, the government gains an area of C and E. However, there is a deadweight loss of the triangles B and D, or in diagram 1, the triangles labeled Societal Loss. Deadweight loss is also called efficiency loss. This cost is incurred because tariffs reduce the incentives for the society to consume and produce.

The net loss to the society due to the tariff would be given by the total costs of the tariff minus its benefits to the society. Therefore, the net welfare loss due to the tariff is equal to:

- Consumer Loss − Government Revenue − Producer Gain

Political analysis

The tariff has been used as a political tool to establish an independent nation; for example, the United States Tariff Act of 1789, signed specifically on July 4, was called the "Second Declaration of Independence" by newspapers because it was intended to be the economic means to achieve the political goal of a sovereign and independent United States.[11]The political impact of tariffs is judged depending on the political perspective; for example the 2002 United States steel tariff imposed a 30% tariff on a variety of imported steel products for a period of three years and American steel producers supported the tariff.[12]

Tariffs can emerge as a political issue prior to an election. In the leadup to the 2007 Australian Federal election, the Australian Labor Party announced it would undertake a review of Australian car tariffs if elected.[13] The Liberal Party made a similar commitment, while independent candidate Nick Xenophon announced his intention to introduce tariff-based legislation as "a matter of urgency".[14]

Unpopular tariffs are known to have ignited social unrest, for example the 1905 meat riots in Chile that developed in protest against tariffs applied to the cattle imports from Argentina.[15][16]

Within technology strategies

When tariffs are an integral element of a country's technology strategy, some economists believe that such tariffs can be highly effective in helping to increase and maintain the country's economic health. Other economists might be less enthusiastic, as tariffs may reduce trade and there may be many spillovers and externalities involved with trade and tariffs. The existence of these externalities makes the imposition of tariffs a rather ambiguous strategy. As an integral part of the technology strategy, tariffs are effective in supporting the technology strategy's function of enabling the country to outmaneuver the competition in the acquisition and utilization of technology in order to produce products and provide services that excel at satisfying the customer needs for a competitive advantage in domestic and foreign markets. The notion that government and policy would be effective at finding new and infant technologies, rather than supporting existing politically motivated industry, rather than, say, international technology venture specialists, is however, unproven.This is related to the infant industry argument.

In contrast, in economic theory tariffs are viewed as a primary element in international trade with the function of the tariff being to influence the flow of trade by lowering or raising the price of targeted goods to create what amounts to an artificial competitive advantage. When tariffs are viewed and used in this fashion, they are addressing the country's and the competitors' respective economic healths in terms of maximizing or minimizing revenue flow rather than in terms of the ability to generate and maintain a competitive advantage which is the source of the revenue. As a result, the impact of the tariffs on the economic health of the country are at best minimal but often are counter-productive.

A program within the US intelligence community, Project Socrates, that was tasked with addressing America's declining economic competitiveness, determined that countries like China and India were using tariffs as an integral element of their respective technology strategies to rapidly build their countries into economic superpowers. However, the US intelligence community tends to have limited inputs into developing US trade policy. It was also determined that the US, in its early years, had also used tariffs as an integral part of what amounted to technology strategies to transform the country into a superpower.