Test written by four-year-old child in 1972, former Soviet Union. The lines are not ideal but the teacher (all red writing) gave the best grade (5) anyway.

Early childhood education (ECE; also nursery education) is a branch of education theory which relates to the teaching of little children (formally and informally) up through the age of eight (birth through Grade 3). Infant/toddler education, a subset of early childhood education, denotes the education of children from birth to age two. It emerged as a field of study during the Enlightenment, particularly in European countries with high literacy rates. It continued to grow through the nineteenth century as universal primary education became a norm in the Western world. In recent years, early childhood education has become a prevalent public policy issue, as municipal, state, and federal lawmakers consider funding for preschool and pre-K. It is described as an important period in a child's development. It refers to the development of a child's personality. ECE is also a professional designation earned through a post secondary education program. For example, in Ontario, Canada, the designations ECE (Early Childhood Educator) and RECE (Registered Early Childhood Educator) may only be used by registered members of the College of Early Childhood Educators, which is made up of accredited child care professionals who are held accountable to the College's standards of practice.

History

The history of early childhood care and education (ECCE) refers to the development of care and education of children from birth through eight years old throughout history[1]. ECCE has a global scope, and caring for and educating young children has always been an integral part of human societies. Arrangements for fulfilling these societal roles have evolved over time and remain varied across cultures, often reflecting family and community structures as well as the social and economic roles of women and men.[8] Historically, such arrangements have largely been informal, involving family, household and community members. The formalization of these arrangements emerged in the nineteenth century with the establishment of kindergartens for educational purposes and day nurseries for care in much of Europe and North America, Brazil, China, India, Jamaica and Mexico.[9][10][11][12]Context

While the first two years of a child's life are spent in the creation of a child's first "sense of self", most children are able to differentiate between themselves and others by their second year. This differentiation is crucial to the child's ability to determine how they should function in relation to other people.[13] Parents can be seen as a child's first teacher and therefore an integral part of the early learning process.[14]

Early childhood attachment processes that occurs during early childhood years 0–2 years of age, can be influential to future education. With proper guidance and exploration children begin to become more comfortable with their environment, if they have that steady relationship to guide them. Parents who are consistent with response times, and emotions will properly make this attachment early on. If this attachment is not made, there can be detrimental effects on the child in their future relationships and independence. There are proper techniques that parents and caregivers can use to establish these relationships, which will in turn allow children to be more comfortable exploring their environment. Academic Journal Reference This provides experimental research on the emphasis on caregiving effecting attachment. Education for young students can help them excel academically and socially. With exposure and organized lesson plans children can learn anything they want to. The tools they learn to use during these beginning years will provide lifelong benefits to their success. Developmentally, having structure and freedom, children are able to reach their full potential.

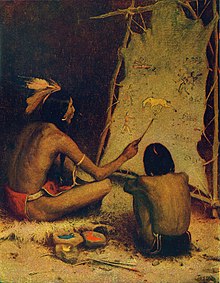

Learning through play

A child exploring comfortably due to having a secure attachment with caregiver.

Early childhood education often focuses on learning through play, based on the research and philosophy of Jean Piaget, which posits that play meets the physical, intellectual, language, emotional and social needs (PILES) of children. Children's curiosity and imagination naturally evoke learning when unfettered. Learning through play will allow a child to develop cognitively.[15] This is the earliest form of collaboration among children. In this, children learn through their interactions with others. Thus, children learn more efficiently and gain more knowledge through activities such as dramatic play, art, and social games.[16]

Tassoni suggests that "some play opportunities will develop specific individual areas of development, but many will develop several areas."[17] Thus, It is important that practitioners promote children’s development through play by using various types of play on a daily basis. Allowing children to help get snacks ready helps develop math skills (one-to-one ratio, patterns, etc.), leadership, and communication.[18] Key guidelines for creating a play-based learning environment include providing a safe space, correct supervision, and culturally aware, trained teachers who are knowledgeable about the Early Years Foundation.

Davy states that the British Children's Act of 1989 links to play-work as the act works with play workers and sets the standards for the setting such as security, quality and staff ratios.[19] Learning through play has been seen regularly in practice as the most versatile way a child can learn. Margaret McMillan (1860-1931) suggested that children should be given free school meals, fruit and milk, and plenty of exercise to keep them physically and emotionally healthy. Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) believed that play time allows children to talk, socially interact, use their imagination and intellectual skills. Maria Montessori (1870-1952) believed that children learn through movement and their senses and after doing an activity using their senses. When young students have group play time it also helps them to be more empathetic towards each other.[20]

In a more contemporary approach, organizations such as the National Association of the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) promote child-guided learning experiences, individualized learning, and developmentally appropriate learning as tenets of early childhood education.[21]

Piaget provides an explanation for why learning through play is such a crucial aspect of learning as a child. However, due to the advancement of technology, the art of play has started to dissolve and has transformed into "playing" through technology. Greenfield, quoted by the author, Stuart Wolpert, in the article, "Is Technology Producing a Decline in Critical Thinking and Analysis?", states, "No media is good for everything. If we want to develop a variety of skills, we need a balanced media diet. Each medium has costs and benefits in terms of what skills each develops." Technology is beginning to invade the art of play and a balance needs to be found.[22]

Many oppose the theory of learning through play because they think children are not gaining new knowledge. In reality, play is the first way children learn to make sense of the world at a young age. As children watch adults interact around them, they pick up on their slight nuances, from facial expressions to their tone of voice. They are exploring different roles, learning how things work, and learning to communicate and work with others. These things cannot be taught by a standard curriculum, but have to be developed through the method of play. Many preschools understand the importance of play and have designed their curriculum around that to allow children to have more freedom. Once these basics are learned at a young age, it sets children up for success throughout their schooling and their life. Many Early Childhood programs provide real life props and activities to enrich the children's play, enabling them to learn various skills through play.[citation needed]

Theories of child development

The Developmental Interaction Approach is based on the theories of Jean Piaget, Erik Erikson, John Dewey and Lucy Sprague Mitchell. The approach focuses on learning through discovery.[23] > Jean Jacques Rousseau recommended that teachers should exploit individual children's interests in order to make sure each child obtains the information most essential to his personal and individual development.[24] The five developmental domains of childhood development include:[25]

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

- Physical: the way in which a child develops biological and physical functions, including eyesight and motor skills

- Social: the way in which a child interacts with others[26] Children develop an understanding of their responsibilities and rights as members of families and communities, as well as an ability to relate to and work with others.[27]

- Emotional: the way in which a child creates emotional connections and develops self-confidence. Emotional connections develop when children relate to other people and share feelings.

- Language: the way in which a child communicates, including how they present their feelings and emotions, both to other people and to themselves. At 3 months, children employ different cries for different needs. At 6 months they can recognize and imitate the basic sounds of spoken language. In the first 3 years, children need to be exposed to communication with others in order to pick up language. "Normal" language development is measured by the rate of vocabulary acquisition.[28]

- Cognitive skills: the way in which a child organizes information. Cognitive skills include problem solving, creativity, imagination and memory.[29] They embody the way in which children make sense of the world. Piaget believed that children exhibit prominent differences in their thought patterns as they move through the stages of cognitive development: sensorimotor period, the pre-operational period, and the operational period.[30]

Vygotsky’s socio-cultural learning theory

Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky proposed a "socio-cultural learning theory" that emphasized the impact of social and cultural experiences on individual thinking and the development of mental processes.[31] Vygotsky's theory emerged in the 1930s and is still discussed today as a means of improving and reforming educational practices.Vygotsky argued that since cognition occurs within a social context, our social experiences shape our ways of thinking about and interpreting the world.[32] Although Vygotsky predated social constructivists, he is commonly classified as one. Social constructivists believe that an individual's cognitive system is a resditional learning time. Vygotsky advocated that teachers facilitate rather than direct student learning.[33] His approach calls for teachers to incorporate students’ needs and interests.

Piaget’s constructivist theory

Jean Piaget's constructivist theory gained influence in the 1970s and '80s. Although Piaget himself was primarily interested in a descriptive psychology of cognitive development, he also laid the groundwork for a constructivist theory of learning.[34] Piaget believed that learning comes from within: children construct their own knowledge of the world through experience and subsequent reflection. He said that "if logic itself is created rather than being inborn, it follows that the first task of education is to form reasoning." Within Piaget's framework, teachers should guide children in acquiring their own knowledge rather than simply transferring knowledge.[35]According to Piaget’s theory, when young children encounter new information, they attempt to accommodate and assimilate it into their existing understanding of the world. Accommodation involves adapting mental schemas and representations in order to make them consistent with reality. Assimilation involves fitting new information into their pre-existing schemas. Through these two processes, young children learn by equilibrating their mental representations with reality. They also learn from mistakes.[36]

A Piagetian approach emphasizes experiential education; in school, experiences become more hands-on and concrete as students explore through trial and error.[37] Thus, crucial components of early childhood education include exploration, manipulating objects, and experiencing new environments. Subsequent reflection on these experiences is equally important.[38]

Piaget’s concept of reflective abstraction was particularly influential in mathematical education.[39] Through reflective abstraction, children construct more advanced cognitive structures out of the simpler ones they already possess. This allows children to develop mathematical constructs that cannot be learned through equilibration — making sense of experiences through assimilation and accommodation — alone.[40]

According to Piagetian theory, language and symbolic representation is preceded by the development of corresponding mental representations. Research shows that the level of reflective abstraction achieved by young children was found to limit the degree to which they could represent physical quantities with written numerals. Piaget held that children can invent their own procedures for the four arithmetical operations, without being taught any conventional rules.[41]

Piaget’s theory implies that computers can be a great educational tool for young children when used to support the design and construction of their projects. McCarrick and Xiaoming found that computer play is consistent with this theory.[42] However, Plowman and Stephen found that the effectiveness of computers is limited in the preschool environment; their results indicate that computers are only effective when directed by the teacher.[43] This suggests, according to the constructivist theory, that the role of preschool teachers is critical in successfully adopting computers.[44]

Kolb's experiential learning theory

David Kolb's experiential learning theory, which was influenced by John Dewey, Kurt Lewin and Jean Piaget, argues that children need to experience things in order to learn: "The process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. Knowledge results from the combinations of grasping and transforming experience." The experimental learning theory is distinctive in that children are seen and taught as individuals. As a child explores and observes, teachers ask the child probing questions. The child can then adapt prior knowledge to learning new information.Kolb breaks down this learning cycle into four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. Children observe new situations, think about the situation, make meaning of the situation, then test that meaning in the world around them.[45]

The practical implications of early childhood education

In recent decades, studies have shown that early childhood education is critical in preparing children to enter and succeed in the (grade school) classroom, diminishing their risk of social-emotional mental health problems and increasing their self-sufficiency later in their lives.[46] In other words, the child needs to be taught to rationalize everything and to be open to interpretations and critical thinking. There is no subject to be considered taboo, starting with the most basic knowledge of the world he lives in, and ending with deeper areas, such as morality, religion and science. Visual stimulus and response time as early as 3 months can be an indicator of verbal and performance IQ at age 4 years.[47]By providing education in a child's most formative years, ECE also has the capacity to pre-emptively begin closing the educational achievement gap between low and high-income students before formal schooling begins.[48] Children of low socioeconomic status (SES) often begin school already behind their higher SES peers; on average, by the time they are three, children with high SES have three times the number of words in their vocabularies as children with low SES.[49] Participation in ECE, however, has been proven to increase high school graduation rates, improve performance on standardized tests, and reduce both grade repetition and the number of children placed in special education.[50]

Especially since the first wave of results from the Perry Preschool Project were published, there has been widespread consensus that the quality of early childhood education programs correlate with gains in low-income children’s IQs and test scores, decreased grade retention, and lower special education rates.

Several studies have reported that children enrolled in ECE increase their IQ scores by 4-11 points by age five, while a Milwaukee study reported a 25-point gain.[51] In addition, students who had been enrolled in the Abecedarian Project, an often-cited ECE study, scored significantly higher on reading and math tests by age fifteen than comparable students who had not participated in early childhood programs.[52] In addition, 36% of students in the Abecedarian Preschool Study treatment group would later enroll in four-year colleges compared to 14% of those in the control group.[52]

Beyond benefitting societal good, ECE also significantly impacts the socioeconomic outcomes of individuals. For example, by age 26, students who had been enrolled in Chicago Child-Parent Centers were less likely to be arrested, abuse drugs, and receive food stamps; they were more likely to have high school diplomas, health insurance and full-time employment.[53]

The Perry Preschool Project

In Ypsilanti, Michigan, 3 and 4 year-olds from low-income families were randomly assigned to participate in the Perry Preschool. By age 18, they were five times less likely to have become chronic law-breakers than those who were not selected to participate in the Preschool.[54]The Perry Preschool Study also found that low-income individuals who were enrolled in a quality preschool program earned on average, by age 40, $5500 per year more than those who were not.[55] The Perry Preschool Study produced a total benefit/cost ratio of 17:1 (4:1 for participants, 13:1 for the public), with participants on average earning higher incomes, more likely to own their own homes, and less likely to be on welfare. [56]

The authors of the Perry Preschool Project also propose that the return on investment in education declines with the student's age. This study is noteworthy because it advocates for public spending on early childhood programs as an economic investment in a society's future, rather than in the interest of social justice.[57]

In 2008, Michael L. Anderson re-examined the data from Perry and similar projects and found "... girls garnered substantial short- and long-term benefits from the interventions. However, there were no significant long-term benefits for boys."[58]

Early childhood education policy in the United States

In the past decade, there has been a national push for state and federal policy to address the early years as a key component of public education. At the federal level, the Obama administration made the Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge a key tenet of their education reform initiative, awarding $500 million to states with comprehensive early childhood education plans.[59] In addition, a largely Democratic contingent sponsored the Strong Start for America’s Children Act in 2013, which provides free early childhood education for low-income families.[60] Specifically, the Act would generate the impetus and support for states to expand ECE; provide funding through formula grants and Title II (Learning Quality Partnerships), III (Child Care) and IV (Maternal, Infant and Home Visiting) funds; and hold participating states accountable for Head Start early learning standards.[61]Head Start grants are awarded directly to public or private non-profit organizations, including community-based and faith-based organizations, or for-profit agencies within a community that wish to compete for funds. The same categories of organizations are eligible to apply for Early Head Start, except that applicants need not be from the community they will be serving.[62]

Many states have created new early childhood education agencies. Massachusetts was the first state to create a consolidated department focused on early childhood learning and care. Just in the past fiscal year, state funding for public In Minnesota, the state government created an Early Learning scholarship program, where families with young children meeting free and reduced price lunch requirements for kindergarten can receive scholarships to attend ECE programs.[63] In California, Senator Darrell Steinberg led a coalition to pass the Kindergarten Readiness Act, which creates a state early childhood system supporting children from birth to age five and provides access to ECE for all 4-year-olds in the state. It also created an Early Childhood Office charged with creating an ECE curriculum that would be aligned with the K-12 continuum.[64]

State funding for pre-K increased by $363.6 million to a total of $5.6 billion, a 6.9% increase from 2012 to 2013. 40 states fund pre-K programs.[65]

Currently, one of America's larger challenges regarding ECE is a dearth in workforce, partly due to low compensation for rigorous work. The average early childhood teaching assistant earns an annual salary of $10,500 while the highest paid early childhood educators earn an average $18,000 per year. The turnover of ECE staff averages 31% per year.[66] Another challenge is to ensure the quality of ECE programs. Because ECE is a relatively new field, there is little research and consensus into what makes a good program. However, the National Association of the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) is a national organization that has identified evidence-based ECE standards and accredits quality programs.[67] Continuing the leadership role it established with the Common Core, the federal government could play a key role in establishing ECE standards for states.

The American legal system has also played a hand in public ECE. State adequacy cases can also create a powerful legal impetus for states to provide universal access to ECE, drawing upon the rich research illustrating that by the time they enter school, students from low-income backgrounds are already far behind other students. The New Jersey case Abbott County School District v. Burke and South Carolina case Abbeville County School District v. State have established early but incomplete precedents in looking at "adequate education" as education that addresses needs best identified in early childhood, including immediate and continuous literacy interventions.

In the 1998 case of Abbott v. Burke (Abbott V), the New Jersey Supreme Court required New Jersey’s poorest school districts to implement high-quality ECE programs and full day kindergarten for all three and four-year-olds. Beyond ruling that New Jersey needed to allocate more funds to preschools in low-income communities in order to reach "educational adequacy," the Supreme court also authorized the state department of education to cooperate "with… existing early childhood and daycare programs in the community" to implement universal access.[68]

In the 2005 case of Abbeville v. State, the South Carolina Supreme Court decided that ECE programs were necessary to break the "debilitating and destructive cycle of poverty for low-income students and poor academic achievement." Besides mandating that all low-income children have access to ECE by age three, the court also held that early childhood interventions—such as counseling, special needs identification, and socio-emotional supports—continue through grade three (Abbeville, 2005). The court furthermore argued that ECE was not only imperative for educational adequacy but also that "the dollars spent in early childhood intervention are the most effective expenditures in the educational process."[69]

Early childhood care and education as a holistic and multisectoral service

Unlike other areas of education, early childhood care and education (ECCE) places strong emphasis on developing the whole child – attending to his or her social, emotional, cognitive and physical needs – in order to establish a solid and broad foundation for lifelong learning and well-being. ‘Care’ includes health, nutrition and hygiene in a warm, secure and nurturing environment; and ‘education’ includes stimulation, socialization, guidance, participation, learning and developmental activities. ECCE begins at birth and can be organized in a variety of non-formal, formal and informal modalities, such as parenting education, health-based mother and child intervention, care institutions, child-to-child programmes, home-based or centre-based childcare, kindergartens and pre-schools. Different terms to describe ECCE are used by different countries, institutions and stakeholders, such as early childhood development (ECD), early childhood education and care (ECEC), early childhood care and development (ECCD), with Early Childhood Care and Education as the UNESCO nomenclature.[70]As research shows, children’s care and educational needs are intertwined. Poor care, health, nutrition, and physical and emotional security can affect educational potentials in the form of mental retardation, impaired cognitive and behavioural capacities, motor development delay, depression, difficulties with concentration and attention. Inversely, early health and nutrition interventions, such as iron supplementation, deworming treatment and school feeding, have been shown to directly contribute to increased pre-school attendance.[71] Studies have demonstrated better child outcomes through the combined intervention of cognitive stimulation and nutritional supplementation than through either cognitive stimulation or nutritional supplementation alone. Quality ECCE is one that integrates educational activities, nutrition, health care and social services.[70]

Economic benefits of early childhood care and education

Decades of research provide unequivocal evidence that public investment in early childhood care and education can produce economic returns equal to roughly 10 times its costs.[72][73] The sources of these gains are (1) child care that enables mothers to work and (2) education and other supports for child development that increase subsequent school success, labour force productivity, prosocial behaviour, and health. The benefits from enhanced child development are the largest part of the economic return, but both are important considerations in policy and programme design.The economic consequences include reductions in public and private expenditures associated with school failure, crime, and health problems as well as increases in earnings.[74]International agreements

The first World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education took place in Moscow from 27 to 29 September 2010, jointly organized by UNESCO and the city of Moscow. The overarching goals of the conference are to:According to UNESCO a preschool curriculum is one that delivers educational content through daily activities, and furthers a child's physical, cognitive and social development. Generally, preschool curricula are only recognized by governments if they are based on academic research and reviewed by peers.[76]

- Reaffirm ECCE as a right of all children and as the basis for development

- Take stock of the progress of Member States towards achieving the EFA Goal 1

- Identify binding constraints toward making the intended equitable expansion of access to quality ECCE services

- Establish, more concretely, benchmarks and targets for the EFA Goal 1 toward 2015 and beyond

- Identify key enablers that should facilitate Member States to reach the established targets

- Promote global exchange of good practices[75]

Preschool for Child Rights have pioneered into preschool curricular areas and is contributing into child rights through their preschool curriculum.[77]

Curricula in early childhood care and education

Curricula in early childhood care and education (ECCE) is the driving force behind any ECCE programme. It is ‘an integral part of the engine that, together with the energy and motivation of staff, provides the momentum that makes programmes live’.[78] It follows therefore that the quality of a programme is greatly influenced by the quality of its curriculum. In early childhood, these may be programmes for children or parents, including health and nutrition interventions and prenatal programmes, as well as centre-based programmes for children.[79]Barriers and challenges

Children’s learning potential and outcomes are negatively affected by exposure to violence, abuse and child labour. Thus, protecting young children from violence and exploitation is part of broad educational concerns. Due to difficulties and sensitivities around the issue of measuring and monitoring child protection violations and gaps in defining, collecting and analysing appropriate indicators,[80] data coverage in this area is scant. However, proxy indicators can be used to assess the situation. For example, ratification of relevant international conventions indicates countries’ commitment to child protection. By April 2014, 194 countries had ratified the CRC3; and 179 had ratified the 1999 International Labour Organization’s Convention (No. 182) concerning the elimination of the worst forms of child labour. But, many of these ratifications are yet to be given full effect through actual implementation of concrete measures. Globally, 150 million children aged 5–14 are estimated to be engaged in child labour.[80] In conflict-affected poor countries, children are twice as likely to die before their fifth birthday compared to those in other poor countries.[81] In industrialized countries, 4 per cent of children are physically abused each year and 10 per cent are neglected or psychologically abused.[80][82]In both developed and developing countries, children of the poor and the disadvantaged remain the least served. This exclusion persists against the evidence that the added value of early childhood care and education services are higher for them than for their more affluent counterparts, even when such services are of modest quality. While the problem is more intractable in developing countries, the developed world still does not equitably provide quality early childhood care and education services for all its children. In many European countries, children, mostly from low-income and immigrant families, do not have access to good quality early childhood care and education.[83][82]

Early Education under Trump Administration

The 2019 budget approved by President Donald Trump included a 21 percent cut in Department of Health and Human Services funding[84]. This is where most early education and care programs like Head Start[85] are included. The department’s budget highlights doing away with the pre-school development grant program which aided 18 states in spreading out access to pre-K for 4-year old children during the last few years. It helped said states in improving overall quality of pre-K programs. This program was initiated during the Obama administration because of Every Student Succeeds Act or ESSA under the DHHS[86].The federal government called for a minimal increase in Head Start funding with approximately $9.3 billion for said program. This subsidy is estimated to serve around 861,000 kids. However, the administration withdrew the requirement that such program started serving children for a longer day and school year due to insufficient funding[87]. The Center for American Progress said President Trump and the House of Representatives advocated deep cuts in programs that were supposed to help impoverished families rather than attend to the needs of low and middle-income households through paid leave and child care as well as increasing minimum wage.