Mesoamerica and its cultural areas

Page 9 of the Dresden Codex (from the 1880 Förstermann edition)

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in the Americas, extending from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica, and within which pre-Columbian societies flourished before the Spanish colonization of the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries. It is one of six areas in the world where ancient civilization arose independently, and the second in the Americas along with Norte Chico (Caral-Supe) in present-day northern coastal Peru.

As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures. Beginning as early as 7000 BC, the domestication of cacao, maize, beans, tomato, avocado, vanilla, squash and chili, as well as the turkey and dog, caused a transition from paleo-Indian hunter-gatherer tribal grouping to the organization of sedentary agricultural villages. In the subsequent Formative period, agriculture and cultural traits such as a complex mythological and religious tradition, a vigesimal numeric system, and a complex calendric system, a tradition of ball playing, and a distinct architectural style, were diffused through the area. Also in this period, villages began to become socially stratified and develop into chiefdoms with the development of large ceremonial centers, interconnected by a network of trade routes for the exchange of luxury goods, such as obsidian, jade, cacao, cinnabar, Spondylus shells, hematite, and ceramics. While Mesoamerican civilization did know of the wheel and basic metallurgy, neither of these technologies became culturally important.[3]

Among the earliest complex civilizations was the Olmec culture, which inhabited the Gulf coast of Mexico and extended inland and southwards across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Frequent contact and cultural interchange between the early Olmec and other cultures in Chiapas, Guatemala and Oaxaca laid the basis for the Mesoamerican cultural area. All this was facilitated by considerable regional communications in ancient Mesoamerica, especially along the Pacific coast.

Ballgame court at Monte Albán

A pair of swinging Remojadas figurines, Classic Veracruz culture, 300 CE to 900 CE.

Mesoamerica is one of only three regions of the world where writing is known to have independently developed (the others being ancient Sumer and China).[4] In Central Mexico, the height of the Classic period saw the ascendancy of the city of Teotihuacan, which formed a military and commercial empire whose political influence stretched south into the Maya area and northward. Upon the collapse of Teotihuacán around AD 600, competition between several important political centers in central Mexico, such as Xochicalco and Cholula, ensued. At this time during the Epi-Classic period, the Nahua peoples began moving south into Mesoamerica from the North, and became politically and culturally dominant in central Mexico, as they displaced speakers of Oto-Manguean languages. During the early post-Classic period, Central Mexico was dominated by the Toltec culture, Oaxaca by the Mixtec, and the lowland Maya area had important centers at Chichén Itzá and Mayapán. Towards the end of the post-Classic period, the Aztecs of Central Mexico built a tributary empire covering most of central Mesoamerica.[5]

The distinct Mesoamerican cultural tradition ended with the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. Over the next centuries, Mesoamerican indigenous cultures were gradually subjected to Spanish colonial rule. Aspects of the Mesoamerican cultural heritage still survive among the indigenous peoples who inhabit Mesoamerica, many of whom continue to speak their ancestral languages, and maintain many practices harking back to their Mesoamerican roots.[6]

Etymology and definition

Maya Ruins of Tazumal in Santa Ana, El Salvador

The term Mesoamerica literally means "middle America" in Greek. Middle America often refers to a larger area in the Americas, but it has also previously been used more narrowly to refer to Mesoamerica. An example is the title of the 16 volumes of The Handbook of Middle American Indians. "Mesoamerica" is broadly defined as the area that is home to the Mesoamerican civilization, which comprises a group of peoples with close cultural and historical ties. The exact geographic extent of Mesoamerica has varied through time, as the civilization extended North and South from its heartland in southern Mexico. The term was first used by the German ethnologist Paul Kirchhoff, who noted that similarities existed among the various pre-Columbian cultures within the region that included southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, western Honduras, and the Pacific lowlands of Nicaragua and northwestern Costa Rica. In the tradition of cultural history, the prevalent archaeological theory of the early to middle 20th century, Kirchhoff defined this zone as a cultural area based on a suite of interrelated cultural similarities brought about by millennia of inter- and intra-regional interaction (i.e., diffusion).[7][8] Mesoamerica is recognized as a near-prototypical cultural area, and the term is now fully integrated in the standard terminology of pre-Columbian anthropological studies. Conversely, the sister terms Aridoamerica and Oasisamerica, which refer to northern Mexico and the western United States, respectively, have not entered into widespread usage.

Some of the significant cultural traits defining the Mesoamerican cultural tradition are:

- sedentism based on maize agriculture

- the construction of stepped pyramids

- the use of two different calendars (a 260-day ritual calendar and a 365-day calendar based on the solar year)

- vigesimal (base 20) number system

- the use of locally developed pictographic and hieroglyphic (logo-syllabic) writing systems

- the use of rubber and the practice of the Mesoamerican ballgame

- the use of bark paper and agave for ritual purposes and as a medium for writing and the latter also for cooking and clothing

- the practice of various forms of ritualistic sacrifice, including Human sacrifice

- a religious complex based on a combination of shamanism and natural deities, and a shared system of symbols

- a linguistic area defined by a number of grammatical traits that have spread through the area by diffusion[9]

Geography

El Mirador flourished from 600 BC to AD 100, and may have had a population of over 100,000.

Landscape of the Mesoamerican highlands

Located on the Middle American isthmus joining North and South America between ca. 10° and 22° northern latitude, Mesoamerica possesses a complex combination of ecological systems, topographic zones, and environmental contexts. A main distinction groups these different niches into two broad categories: the lowlands (those areas between sea level and 1000 meters) and the altiplanos, or highlands (situated between 1,000 and 2,000 meters above sea level).[10][11] In the low-lying regions, sub-tropical and tropical climates are most common, as is true for most of the coastline along the Pacific and Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. The highlands show much more climatic diversity, ranging from dry tropical to cold mountainous climates; the dominant climate is temperate with warm temperatures and moderate rainfall. The rainfall varies from the dry Oaxaca and north Yucatán to the humid southern Pacific and Caribbean lowlands.

Cultural sub-areas

Several distinct sub-regions within Mesoamerica are defined by a convergence of geographic and cultural attributes. These sub-regions are more conceptual than culturally meaningful, and the demarcation of their limits is not rigid. The Maya area, for example, can be divided into two general groups: the lowlands and highlands. The lowlands are further divided into the southern and northern Maya lowlands. The southern Maya lowlands are generally regarded as encompassing northern Guatemala, southern Campeche and Quintana Roo in Mexico, and Belize. The northern lowlands cover the remainder of the northern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula. Other areas include Central Mexico, West Mexico, the Gulf Coast Lowlands, Oaxaca, the Southern Pacific Lowlands, and Southeast Mesoamerica (including northern Honduras).Topography

There is extensive topographic variation in Mesoamerica, ranging from the high peaks circumscribing the Valley of Mexico and within the central Sierra Madre mountains to the low flatlands of the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The tallest mountain in Mesoamerica is Pico de Orizaba, a dormant volcano located on the border of Puebla and Veracruz. Its peak elevation is 5,636 m (18,490 ft).The Sierra Madre mountains, which consist of several smaller ranges, run from northern Mesoamerica south through Costa Rica. The chain is historically volcanic. In central and southern Mexico, a portion of the Sierra Madre chain is known as the Eje Volcánico Transversal, or the Trans-Mexican volcanic belt. There are 83 inactive and active volcanoes within the Sierra Madre range, including 11 in Mexico, 37 in Guatemala, 23 in El Salvador, 25 in Nicaragua, and 3 in northwestern Costa Rica. According to the Michigan Technological University,[12] 16 of these are still active. The tallest active volcano is Popocatépetl at 5,452 m (17,887 ft). This volcano, which retains its Nahuatl name, is located 70 km (43 mi) southeast of Mexico City. Other volcanoes of note include Tacana on the Mexico–Guatemala border, Tajumulco and Santamaría in Guatemala, Izalco in El Salvador, Momotombo in Nicaragua, and Arenal in Costa Rica.

One important topographic feature is the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a low plateau that breaks up the Sierra Madre chain between the Sierra Madre del Sur to the north and the Sierra Madre de Chiapas to the south. At its highest point, the Isthmus is 224 m (735 ft) above mean sea level. This area also represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean in Mexico. The distance between the two coasts is roughly 200 km (120 mi). Although the northern side of the Isthmus is swampy and covered with dense jungle, the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, as the lowest and most level point within the Sierra Madre mountain chain, was nonetheless a main transportation, communication, and economic route within Mesoamerica.

Bodies of water

Outside of the northern Maya lowlands, rivers are common throughout Mesoamerica. Some of the more important ones served as loci of human occupation in the area. The longest river in Mesoamerica is the Usumacinta, which forms in Guatemala at the convergence of the Salinas or Chixoy and La Pasion River and runs north for 970 km (600 mi) – 480 km (300 mi) of which are navigable – eventually draining into the Gulf of Mexico. Other rivers of note include the Rio Grande de Santiago, the Grijalva River, the Motagua River, the Ulúa River, and the Hondo River. The northern Maya lowlands, especially the northern portion of the Yucatán peninsula, are notable for their nearly complete lack of rivers (largely due to the absolute lack of topographic variation). Additionally, no lakes exist in the northern peninsula. The main source of water in this area is aquifers that are accessed through natural surface openings called cenotes.With an area of 8,264 km2 (3,191 sq mi), Lake Nicaragua is the largest lake in Mesoamerica. Lake Chapala is Mexico’s largest freshwater lake, but Lake Texcoco is perhaps most well known as the location upon which Tenochtitlan, capital of the Aztec Empire, was founded. Lake Petén Itzá, in northern Guatemala, is notable as the location at which the last independent Maya city, Tayasal (or Noh Petén), held out against the Spanish until 1697. Other large lakes include Lake Atitlán, Lake Izabal, Lake Güija, Lemoa, and Lake Managua.

Biodiversity

Almost all ecosystems are present in Mesoamerica; the more well known are the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, the second largest in the world, and La Mosquitia (consisting of the Rio Platano Biosphere Reserve, Tawahka Asangni, Patuca National Park, and Bosawas Biosphere Reserve) a rainforest second in size in the Americas only to the Amazonas.[13] The highlands present mixed and coniferous forest. The biodiversity is among the richest in the world, although the number of species in the red list of the IUCN is growing every year.Chronology and culture

Tikal is one of the largest archaeological sites, urban centers, and tourist attractions of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization. It is located in the archaeological region of the Petén Basin in what is now northern Guatemala.

The history of human occupation in Mesoamerica is divided into stages or periods. These are known, with slight variation depending on region, as the Paleo-Indian, the Archaic, the Preclassic (or Formative), the Classic, and the Postclassic. The last three periods, representing the core of Mesoamerican cultural fluorescence, are further divided into two or three sub-phases. Most of the time following the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century is classified as the Colonial period.

The differentiation of early periods (i.e., up through the end of the Late Preclassic) generally reflects different configurations of socio-cultural organization that are characterized by increasing socio-political complexity, the adoption of new and different subsistence strategies, and changes in economic organization (including increased interregional interaction). The Classic period through the Postclassic are differentiated by the cyclical crystallization and fragmentation of the various political entities throughout Mesoamerica.

Paleo-Indian

The Mesoamerican Paleo-Indian period precedes the advent of agriculture and is characterized by a nomadic hunting and gathering subsistence strategy. Big-game hunting, similar to that seen in contemporaneous North America, was a large component of the subsistence strategy of the Mesoamerican Paleo-Indian. These sites had obsidian blades and Clovis-style fluted projectile points.Archaic

The Archaic period (8000–2000 BC) is characterized by the rise of incipient agriculture in Mesoamerica. The initial phases of the Archaic involved the cultivation of wild plants, transitioning into informal domestication and culminating with sedentism and agricultural production by the close of the period. Transformations of natural environments have been a common feature at least since the mid Holocene [14]. Archaic sites include Sipacate in Escuintla, Guatemala, where maize pollen samples date to c. 3500 BC.[15]Preclassic/Formative

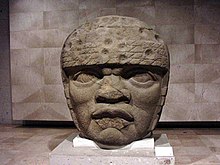

Olmec Colossal Head No. 3 1200–900 BC

The first complex civilization to develop in Mesoamerica was that of the Olmec, who inhabited the gulf coast region of Veracruz throughout the Preclassic period. The main sites of the Olmec include San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes. Although specific dates vary, these sites were occupied from roughly 1200 to 400 BC. Remains of other early cultures interacting with the Olmec have been found at Takalik Abaj, Izapa, and Teopantecuanitlan, and as far south as in Honduras.[16] Research in the Pacific Lowlands of Chiapas and Guatemala suggest that Izapa and the Monte Alto Culture may have preceded the Olmec. Radiocarbon samples associated with various sculptures found at the Late Preclassic site of Izapa suggest a date of between 1800 and 1500 BC.[17]

During the Middle and Late Preclassic period, the Maya civilization developed in the southern Maya highlands and lowlands, and at a few sites in the northern Maya lowlands. The earliest Maya sites coalesced after 1000 BC, and include Nakbe, El Mirador, and Cerros. Middle to Late Preclassic Maya sites include Kaminaljuyú, Cival, Edzná, Cobá, Lamanai, Komchen, Dzibilchaltun, and San Bartolo, among others.

The Preclassic in the central Mexican highlands is represented by such sites as Tlapacoya, Tlatilco, and Cuicuilco. These sites were eventually superseded by Teotihuacán, an important Classic-era site that eventually dominated economic and interaction spheres throughout Mesoamerica. The settlement of Teotihuacan is dated to the later portion of the Late Preclassic, or roughly AD 50.

In the Valley of Oaxaca, San José Mogote represents one of the oldest permanent agricultural villages in the area, and one of the first to use pottery. During the Early and Middle Preclassic, the site developed some of the earliest examples of defensive palisades, ceremonial structures, the use of adobe, and hieroglyphic writing. Also of importance, the site was one of the first to demonstrate inherited status, signifying a radical shift in socio-cultural and political structure. San José Mogote was eventual overtaken by Monte Albán, the subsequent capital of the Zapotec empire, during the Late Preclassic.

The Preclassic in western Mexico, in the states of Nayarit, Jalisco, Colima, and Michoacán also known as the Occidente, is poorly understood. This period is best represented by the thousands of figurines recovered by looters and ascribed to the "shaft tomb tradition".

Preclassic gallery

- Sculpture of "The Acrobat" from Tlatilco.

- Cuicuilco 800–600 BC

- Nakbé, Mid Preclassic (600 BC) Palace remains, The Mirador Basin

- The partly excavated main structure of San Jose Mogote 1500–500 BC

- Monte Alban, Building J in the foreground. 200 BC – AD 200

Classic

Early Classic

Pyramid of the Moon viewed from atop of the Pyramid of the Sun.

The Classic period is marked by the rise and dominance of several polities. The traditional distinction between the Early and Late Classic are marked by their changing fortune and their ability to maintain regional primacy. Of paramount importance are Teotihuacán in central Mexico and Tikal in Guatemala; the Early Classic’s temporal limits generally correlate to the main periods of these sites. Monte Alban in Oaxaca is another Classic-period polity that expanded and flourished during this period, but the Zapotec capital exerted less interregional influence than the other two sites.

During the Early Classic, Teotihuacan participated in and perhaps dominated a far-reaching macro-regional interaction network. Architectural and artifact styles (talud-tablero, tripod slab-footed ceramic vessels) epitomized at Teotihuacan were mimicked and adopted at many distant settlements. Pachuca obsidian, whose trade and distribution is argued to have been economically controlled by Teotihuacan, is found throughout Mesoamerica.

Tikal came to dominate much of the southern Maya lowlands politically, economically, and militarily during the Early Classic. An exchange network centered at Tikal distributed a variety of goods and commodities throughout southeast Mesoamerica, such as obsidian imported from central Mexico (e.g., Pachuca) and highland Guatemala (e.g., El Chayal, which was predominantly used by the Maya during the Early Classic), and jade from the Motagua valley in Guatemala. Tikal was often in conflict with other polities in the Petén Basin, as well as with others outside of it, including Uaxactun, Caracol, Dos Pilas, Naranjo, and Calakmul. Towards the end of the Early Classic, this conflict lead to Tikal’s military defeat at the hands of Caracol in 562, and a period commonly known as the Tikal Hiatus.

Early Classic gallery

- Great Goddess of Teotihuacan AD 200–500

- A reconstruction of Guachimontones, flourished from AD 200–400

- Acanceh, AD 200–300[18]

- Mask located on the "Temple of the Masks" Kohunlich c. AD 500

Late Classic

Xochicalco, Temple of the Feathered Serpent, AD 650–900

The Late Classic period (beginning ca. AD 600 until AD 909 [varies]) is characterized as a period of interregional competition and factionalization among the numerous regional polities in the Maya area. This largely resulted from the decrease in Tikal’s socio-political and economic power at the beginning of the period. It was therefore during this time that other sites rose to regional prominence and were able to exert greater interregional influence, including Caracol, Copán, Palenque, and Calakmul (which was allied with Caracol and may have assisted in the defeat of Tikal), and Dos Pilas Aguateca and Cancuén in the Petexbatún region of Guatemala. Around 710, Tikal arose again and started to build strong alliances and defeat its worst enemies. In the Maya area, the Late Classic ended with the so-called "Maya collapse", a transitional period coupling the general depopulation of the southern lowlands and development and florescence of centers in the northern lowlands.

Late Classic gallery

- Copan Stela H commissioned by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil AD 695–738

- Jaina Island type figure (Maya) AD 650–800

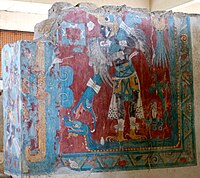

- Cacaxtla, Mural depicting the Bird Man AD 650–900

Terminal Classic

Detail of the Nunnery Quadrangle at Uxmal, 10th century

Generally applied to the Maya area, the Terminal Classic roughly spans the time between AD 800/850 and ca. AD 1000. Overall, it generally correlates with the rise to prominence of Puuc settlements in the northern Maya lowlands, so named after the hills in which they are mainly found. Puuc settlements are specifically associated with a unique architectural style (the "Puuc architectural style") that represents a technological departure from previous construction techniques. Major Puuc sites include Uxmal, Sayil, Labna, Kabah, and Oxkintok. While generally concentrated within the area in and around the Puuc hills, the style has been documented as far away as at Chichen Itza to the east and Edzna to the south.

Chichén Itzá was originally thought to have been a Postclassic site in the northern Maya lowlands. Research over the past few decades has established that it was first settled during the Early/Late Classic transition but rose to prominence during the Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic. During its apogee, this widely known site economically and politically dominated the northern lowlands. Its participation in the circum-peninsular exchange route, possible through its port site of Isla Cerritos, allowed Chichén Itzá to remain highly connected to areas such as central Mexico and Central America. The apparent "Mexicanization" of architecture at Chichén Itzá led past researchers to believe that Chichén Itzá existed under the control of a Toltec empire. Chronological data refutes this early interpretation, and it is now known that Chichén Itzá predated the Toltec; Mexican architectural styles are now used as an indicator of strong economic and ideological ties between the two regions.

Terminal Classic gallery

- Governor's Palace rear view and details, AD 10th century, Uxmal

- Codz Poop, AD 7th–10th centuries Kabah

- Sayil, three-story palace, AD 600–900

Postclassic

The Postclassic (beginning AD 900–1000, depending on area) is, like the Late Classic, characterized by the cyclical crystallization and fragmentation of various polities. The main Maya centers were located in the northern lowlands. Following Chichén Itzá, whose political structure collapsed during the Early Postclassic, Mayapán rose to prominence during the Middle Postclassic and dominated the north for c. 200 years. After Mayapán’s fragmentation, political structure in the northern lowlands revolved around large towns or city-states, such as Oxkutzcab and Ti’ho (Mérida, Yucatán), that competed with one another.

Mesoamerica and Central America in the 16th century before Spanish arrival

Toniná, in the Chiapas highlands, and Kaminaljuyú in the central Guatemala highlands, were important southern highland Maya centers. The latter site, Kaminaljuyú, is one of the longest occupied sites in Mesoamerica and was continuously inhabited from c. 800 BC to around AD 1200. Other important highland Maya groups include the K'iche' of Utatlán, the Mam in Zaculeu, the Poqomam in Mixco Viejo, and the Kaqchikel at Iximche in the Guatemalan highlands. The Pipil resided in El Salvador, while the Ch'orti' were in eastern Guatemala and northwestern Honduras.

In central Mexico, the early portion of the Postclassic correlates with the rise of the Toltec and an empire based at their capital, Tula (also known as Tollan). Cholula, initially an important Early Classic center contemporaneous with Teotihuacan, maintained its political structure (it did not collapse) and continued to function as a regionally important center during the Postclassic. The latter portion of the Postclassic is generally associated with the rise of the Mexica and the Aztec Empire. One of the more commonly known cultural groups in Mesoamerica, the Aztec politically dominated nearly all of central Mexico, the Gulf Coast, Mexico’s southern Pacific Coast (Chiapas and into Guatemala), Oaxaca, and Guerrero.

The Tarascans (also known as the P'urhépecha) were located in Michoacán and Guerrero. With their capital at Tzintzuntzan, the Tarascan state was one of the few to actively and continuously resist Aztec domination during the Late Postclassic. Other important Postclassic cultures in Mesoamerica include the Totonac along the eastern coast (in the modern-day states of Veracruz, Puebla, and Hidalgo). The Huastec resided north of the Totonac, mainly in the modern-day states of Tamaulipas and northern Veracruz. The Mixtec and Zapotec cultures, centered at Mitla and Zaachila respectively, inhabited Oaxaca.

The Postclassic ends with the arrival of the Spanish and their subsequent conquest of the Aztec between 1519 and 1521. Many other cultural groups did not acquiesce until later. For example, Maya groups in the Petén area, including the Itza at Tayasal and the Kowoj at Zacpeten, remained independent until 1697.

Some Mesoamerican cultures never achieved dominant status or left impressive archaeological remains but are nevertheless noteworthy. These include the Otomi, Mixe–Zoque groups (which may or may not have been related to the Olmecs), the northern Uto-Aztecan groups, often referred to as the Chichimeca, that include the Cora and Huichol, the Chontales, the Huaves, and the Pipil, Xincan and Lencan peoples of Central America.

Postclassic gallery

- Palace of Mitla, Oaxaca 12th century

- The Calendar temple of Tlatelolco, 1200 AC.

- Detail of page 20 from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, 14-15th century

- Aztec sun stone, early 16th century

Chronology in chart form

| Period | Timespan | Important cultures, cities |

|---|---|---|

| Paleo-Indian | 10,000–3500 BCE | Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, obsidian and pyrite points, Iztapan |

| Archaic | 3500–1800 BCE | Agricultural settlements, Tehuacán |

| Preclassic (Formative) | 2000 BCE - 250 CE | Unknown culture in La Blanca and Ujuxte, Monte Alto culture |

| Early Preclassic | 2000–1000 BCE | Olmec area: San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan; Central Mexico: Chalcatzingo; Valley of Oaxaca: San José Mogote. The Maya area: Nakbe, Cerros |

| Middle Preclassic | 1000–400 BCE | Olmec area: La Venta, Tres Zapotes; Maya area: El Mirador, Izapa, Lamanai, Xunantunich, Naj Tunich, Takalik Abaj, Kaminaljuyú, Uaxactun; Valley of Oaxaca: Monte Albán |

| Late Preclassic | 400 BC – 200 CE | Maya area: Uaxactun, Tikal, Edzná, Cival, San Bartolo, Altar de Sacrificios, Piedras Negras, Ceibal, Rio Azul; Central Mexico: Teotihuacan; Gulf Coast: Epi-Olmec culture; Western Mexico: Shaft Tomb Tradition |

| Classic | 200–900 CE | Classic Maya Centers, Teotihuacan, Zapotec |

| Early Classic | 200–600 CE | Maya area: Calakmul, Caracol, Chunchucmil, Copán, Naranjo, Palenque, Quiriguá, Tikal, Uaxactun, Yaxha; Central Mexico: Teotihuacan apogee; Zapotec apogee; Western Mexico: Teuchitlan tradition |

| Late Classic | 600–900 CE | Maya area: Uxmal, Toniná, Cobá, Waka', Pusilhá, Xultún, Dos Pilas, Cancuen, Aguateca, Yaxchilan; Central Mexico: Xochicalco, Cacaxtla; Gulf Coast: El Tajín and Classic Veracruz culture; Western Mexico: Teuchitlan tradition |

| Terminal Classic | 800–900/1000 CE | Maya area: Puuc sites: Uxmal, Labna, Sayil, Kabah |

| Postclassic | 900–1519 AD | Aztec, Tarascans, Mixtec, Totonac, Pipil, Itzá, Kowoj, K'iche', Kaqchikel, Poqomam, Mam |

| Early Postclassic | 900–1200 CE | Cholula, Tula, Mitla, El Tajín, Tulum, Topoxte, Kaminaljuyú, Joya de Cerén |

| Late Postclassic | 1200–1521 CE | Tenochtitlan, Cempoala, Tzintzuntzan, Mayapán, Ti'ho, Utatlán, Iximche, Mixco Viejo, Zaculeu |

| Colonial | 1521-1821 | Nahuas, Mayas, Mixtec, Zapotec, Purépecha, Chinantec, Otomi, Tepehua, Totonac, Mazatec, Tlapanec, Amuzgo |

| Postcolonial | 1821-present | Nahuas, Mayas, Mixtec, Zapotec, Purépecha, Chinantec, Otomi, Tepehua, Totonac, Mazatec, Tlapanec, Amuzgo |

General characteristics

Subsistence

Examples of the diversity of maize

By roughly 6000 BC, hunter-gatherers living in the highlands and lowlands of Mesoamerica began to develop agricultural practices with early cultivation of squash and chilli. The earliest example of maize dates to c. 4000 BC and comes from Guilá Naquitz, a cave in Oaxaca. Earlier maize samples have been documented at the Los Ladrones cave site in Panama, c. 5500 BC.[19] Slightly thereafter, other crops began to be cultivated by the semi-agrarian communities throughout Mesoamerica.[20] Although maize is the most common domesticate, the common bean, tepary bean, scarlet runner bean, jicama, tomato and squash all became common cultivates by 3500 BC. At the same time, cotton, yucca and agave were exploited for fibers and textile materials.[21] By 2000 BC, corn was the staple crop in the region and remained so through modern times. The Ramón or Breadnut tree (Brosimum alicastrum) was an occasional substitute for maize in producing flour. Fruit was also important in the daily diet of Mesoamerican cultures. Some of the main ones consumed include avocado, papaya, guava, mamey, zapote, and annona.

Mesoamerica lacked animals suitable for domestication, most notably domesticated large ungulates – the lack of draft animals to assist in transportation is one notable difference between Mesoamerica and the cultures of the South American Andes. Other animals, including the duck, dogs, and turkey, were domesticated. Turkey was the first, occurring around 3500 BC.[22] Dogs were the primary source of animal protein in ancient Mesoamerica,[23] and dog bones are common in midden deposits throughout the region.

Societies of this region did hunt certain wild species to complement their diet. These animals included deer, rabbit, birds, and various types of insects. They also hunted in order to gain luxury items such as feline fur and bird plumage.[24]

Mesoamerican cultures that lived in the lowlands and coastal plains settled down in agrarian communities somewhat later than did highland cultures due to the fact that there was a greater abundance of fruits and animals in these areas, which made a hunter-gatherer lifestyle more attractive.[25] Fishing also was a major provider of food to lowland and coastal Mesoamericans creating a further disincentive to settle down in permanent communities.

Political organization

Ceremonial centers were the nuclei of Mesoamerican settlements. The temples provided spatial orientation, which was imparted to the surrounding town. The cities with their commercial and religious centers were always political entities, somewhat similar to the European city-state, and each person could identify himself with the city in which he lived.[citation needed]

The ceremonial centers were always built to be visible. The pyramids were meant to stand out from the rest of the city, to represent its gods and their powers. Another characteristic feature of the ceremonial centers is historic layers. All of the ceremonial edifices were built in various phases, one on top of the other, to the point that what we now see is usually the last stage of construction. Ultimately, the ceremonial centers were the architectural translation of the identity of each city, as represented by the veneration of their gods and masters.[citation needed] Stelae were common public monuments throughout Mesoamerica, and served to commemorate notable successes, events and dates associated with the rulers and nobility of the various sites.

Economy

Given that Mesoamerica was broken into numerous and diverse ecological niches, none of the societies that inhabited the area were self-sufficient.[citation needed] For this reason, from the last centuries of the Archaic period onward, regions compensated for the environmental inadequacies by specializing in the extraction of certain abundant natural resources and then trading them for necessary unavailable resources through established commercial trade networks.The following is a list of some of the specialized resources traded from the various Mesoamerican sub-regions and environmental contexts:

- Pacific lowlands: cotton and cochineal

- Maya lowlands and the Gulf Coast: cacao, vanilla, jaguar skins, birds and bird feathers (especially quetzal and macaw)

- Central Mexico: Obsidian (Pachuca)

- Guatemalan highlands: Obsidian (San Martin Jilotepeque, El Chayal, and Ixtepeque), pyrite, and jade from the Motagua River valley

- Coastal areas: salt, dry fish, shell, and dyes

Common characteristics of Mesoamerican culture

Calendrical systems

"Head Variant" or "Patron Gods" glyphs for Maya days

The emblem glyph of Tikal (Mutal)

Agriculturally based people historically divide the year into four seasons. These included the two solstices and the two equinoxes, which could be thought of as the four "directional pillars" that support the year. These four times of the year were, and still are, important as they indicate seasonal changes that directly impact the lives of Mesoamerican agriculturalists.

The Maya closely observed and duly recorded the seasonal markers. They prepared almanacs recording past and recent solar and lunar eclipses, the phases of the moon, the periods of Venus and Mars, the movements of various other planets, and conjunctions of celestial bodies. These almanacs also made future predictions concerning celestial events. These tables are remarkably accurate, given the technology available, and indicate a significant level of knowledge among Maya astronomers.[26]

Among the many types of calendars the Maya maintained, the most important include a 260-day cycle, a 360-day cycle or 'year', a 365-day cycle or year, a lunar cycle, and a Venus cycle, which tracked the synodic period of Venus. Maya of the European contact period said that knowing the past aided in both understanding the present and predicting the future (Diego de Landa). The 260-day cycle was a calendar to govern agriculture, observe religious holidays, mark the movements of celestial bodies and memorialize public officials. The 260-day cycle was also used for divination, and (like the Catholic calendar of saints) to name newborns.[27]

The names given to the days, months, and years in the Mesoamerican calendar came, for the most part, from animals, flowers, heavenly bodies, and cultural concepts that held symbolic significance in Mesoamerican culture. This calendar was used throughout the history of Mesoamerican by nearly every culture. Even today, several Maya groups in Guatemala, including the K'iche', Q'eqchi', Kaqchikel, and the Mixe people of Oaxaca continue using modernized forms of the Mesoamerican calendar.

Writing systems

One of the earliest examples of the Mesoamerican writing systems, the Epi-Olmec script on the La Mojarra Stela 1 dated to around AD 150. Mesoamerica is one of the five places in the world where writing has developed independently.

The Mesoamerican scripts deciphered to date are logosyllabic combining the use of logograms with a syllabary, and they are often called hieroglyphic scripts. Five or six different scripts have been documented in Mesoamerica, but archaeological dating methods, and a certain degree of self-interest, create difficulties in establishing priority and thus the forebear from which the others developed. The best documented and deciphered Mesoamerican writing system, and therefore the most widely known, is the classic Maya script. Others include the Olmec, Zapotec, and Epi-Olmec/Isthmian writing systems. An extensive Mesoamerican literature has been conserved partly in indigenous scripts and partly in the postinvasion transcriptions into Latin script.

The other glyphic writing systems of Mesoamerica, and their interpretation, have been subject to much debate. One important ongoing discussion regards whether non-Maya Mesoamerican texts can be considered examples of true writing or whether non-Maya Mesoamerican texts are best understood as pictographic conventions used to express ideas, specifically religious ones, but not representing the phonetics of the spoken language in which they were read.

Mesoamerican writing is found in several mediums, including large stone monuments such as stelae, carved directly onto architecture, carved or painted over stucco (e.g., murals), and on pottery. No Precolumbian Mesoamerican society is known to have had widespread literacy, and literacy was probably restricted to particular social classes, including scribes, painters, merchants, and the nobility.

The Mesoamerican book was typically written with brush and colored inks on a paper prepared from the inner bark of the ficus amacus. The book consisted of a long strip of the prepared bark, which was folded like a screenfold to define individual pages. The pages were often covered and protected by elaborately carved book boards. Some books were composed of square pages while others were composed of rectangular pages.

Following the Spanish conquests in the sixteenth century, Spanish friars taught indigenous scribes to write their languages in alphabetic texts. Many oral histories of the prehispanic period were subsequently recorded in alphabetic texts. The indigenous in central and southern Mexico continued to produce written texts in the colonial period, many with pictorial elements. An important scholarly reference work is the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources. Mesoamerican codices survive from the Aztec, Maya, Mixtec, and Zapotec regions.

Arithmetic

Mesoamerican arithmetic treated numbers as having both literal and symbolic value, the result of the dualistic nature that characterized Mesoamerican ideology.[citation needed] As mentioned, the Mesoamerican numbering system was vigesimal (i.e., based on the number 20).In representing numbers, a series of bars and dots were employed. Dots had a value of one, and bars had a value of five. This type of arithmetic was combined with a symbolic numerology: '2' was related to origins, as all origins can be thought of as doubling; '3' was related to household fire; '4' was linked to the four corners of the universe; '5' expressed instability; '9' pertained to the underworld and the night; '13' was the number for light, '20' for abundance, and '400' for infinity. The concept of zero was also used, and its representation at the Late Preclassic occupation of Tres Zapotes is one of the earliest uses of zero in human history.

Food, medicine, and science

| “ | Mesoamerica would deserve its place in the human pantheon if its inhabitants had only created maize, in terms of harvest weight the world's most important crop. But the inhabitants of Mexico and northern Central America also developed tomatoes, now basic to Italian cuisine; peppers, essential to Thai and Indian food; all the world's squashes (except for a few domesticated in the United States); and many of the beans on dinner plates around the world. One writer estimated that Indians developed three-fifths of the crops now grown in cultivation, most of them in Mesoamerica. Having secured their food supply, the Mesoamerican societies turned to intellectual pursuits. In a millennium or less, a comparatively short time, they invented their own writing, astronomy and mathematics, including the zero.[28] | ” |

Maize played an important role in Mesoamerican feasts due to its symbolic meaning and abundance.[29]

Fray Bernardino de Sahagún collected extensive information on plants, animals, soil types, among other matters from native informants in Book 11, The Earthly Things, of the twelve-volume General History of the Things of New Spain, known as the Florentine Codex, compiled in the third quarter of the sixteenth century. An earlier work, the Badianus Manuscript or Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis is another Aztec codex with written text and illustrations collected from the indigenous viewpoint.

Mythology and worldview

The xoloitzcuintle is one of the naguales of the god Quetzalcoatl. In this form, it helps the dead cross the Chicnahuapan, a river that separates the world of the living from the dead.

The shared traits in Mesoamerican mythology are characterized by their common basis as a religion that, although in many Mesoamerican groups developed into complex polytheistic religious systems, retained some shamanistic elements.[30]

Zapotec mask of the Bat God.

The great breadth of the Mesoamerican pantheon of deities is due to the incorporation of ideological and religious elements from the first primitive religion of Fire, Earth, Water and Nature. Astral divinities (the sun, stars, constellations, and Venus) were adopted and represented in anthropomorphic, zoomorphic, and anthropozoomorphic sculptures, and in day-to-day objects.[citation needed] The qualities of these gods and their attributes changed with the passage of time and with cultural influences from other Mesoamerican groups. The gods are at once three: creator, preserver, and destroyer, and at the same time just one. An important characteristic of Mesoamerican religion was the dualism among the divine entities. The gods represented the confrontation between opposite poles: the positive, exemplified by light, the masculine, force, war, the sun, etc.; and the negative, exemplified by darkness, the feminine, repose, peace, the moon, etc.

The typical Mesoamerican cosmology sees the world as separated into a day world watched by the sun and a night world watched by the moon. More importantly, the three superposed levels of the world are united by a Ceiba tree (Yaxche' in Mayan). The geographic vision is also tied to the cardinal points. Certain geographical features are linked to different parts of this cosmovision. Thus mountains and tall trees connect the middle and upper worlds; caves connect the middle and nether worlds.

Sacrifice

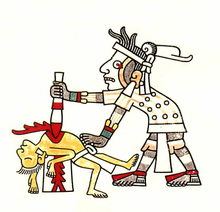

Generally, sacrifice can be divided into two types: autosacrifice and human sacrifice. The different forms of sacrifice are reflected in the imagery used to evoke ideological structure and sociocultural organization in Mesoamerica. In the Maya area, for example, stele depict bloodletting rituals performed by ruling elites, eagles and jaguars devouring human hearts, jade circles or necklaces that represented hearts, and plants and flowers that symbolized both nature and the blood that provided life.[citation needed] Imagery also showed pleas for rain or pleas for blood, with the same intention to replenish the divine energy.Autosacrifice

Ritual human sacrifice portrayed in Codex Laud

Autosacrifice, also called bloodletting, is the ritualized practice of drawing blood from oneself. It is commonly seen or represented through iconography as performed by ruling elites in highly ritualized ceremonies, but it was easily practiced in mundane sociocultural contexts (i.e., non-elites could perform autosacrifice). The act was typically performed with obsidian prismatic blades or stingray spines, and blood was drawn from piercing or cutting the tongue, earlobes, and/or genitals (among other locations). Another form of autosacrifice was conducted by pulling a rope with attached thorns through the tongue or earlobes. The blood produced was then collected on paper held in a bowl.

Autosacrifice was not limited to male rulers, as their female counterparts often performed these ritualized activities. They are typically shown performing the rope and thorns technique. A recently discovered queen's tomb in the Classic Maya site of Waka (also known as El Perú) had a ceremonial stingray spine placed in her genital area, suggesting that women also performed bloodletting in their genitalia.[31]

Human sacrifice

Sacrifice had great importance in the social and religious aspects of Mesoamerican culture. First, it showed death transformed into the divine.[citation needed] Death is the consequence of a human sacrifice, but it is not the end; it is but the continuation of the cosmic cycle. Death creates life – divine energy is liberated through death and returns to the gods, who are then able to create more life. Secondly, it justifies war, since the most valuable sacrifices are obtained through conflict. The death of the warrior is the greatest sacrifice and gives the gods the energy to go about their daily activities, such as the bringing of rain. Warfare and capturing prisoners became a method of social advancement and a religious cause. Finally, it justifies the control of power by the two ruling classes, the priests and the warriors. The priests controlled the religious ideology, and the warriors supplied the sacrifices.Ballgame

A small ceremonial ballcourt at Uaxactun.

Ballgame marker from the classic Lowland Maya site of Chinkultic, Mexico depicting a ballplayer in full gear

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played for over 3000 years by nearly all pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modern version of the game, ulama, continues to be played in a few places.

Over 1300 ballcourts have been found throughout Mesoamerica.[32] They vary considerably in size, but they all feature long narrow alleys with side-walls to bounce the balls against.

The rules of the ballgame are not known, but it was probably similar to volleyball, where the object is to keep the ball in play. In the most well-known version of the game, the players struck the ball with their hips, although some versions used forearms or employed rackets, bats, or handstones. The ball was made of solid rubber, and weighed up to 4 kg or more, with sizes that differed greatly over time or according to the version played.[33][34]

While the game was played casually for simple recreation, including by children and perhaps even women, the game also had important ritual aspects, and major formal ballgames were held as ritual events, often featuring human sacrifice.

Astronomy

Mesoamerican astronomy included a broad understanding of the cycles of planets and other celestial bodies. Special importance was given to the sun, moon, and Venus as the morning and evening star.Observatories were built at some sites, including the round observatory at Ceibal and the “Observatorio” at Xochicalco. Often, the architectural organization of Mesoamerican sites was based on precise calculations derived from astronomical observations. Well-known examples of these include the El Castillo pyramid at Chichen Itza and the Observatorio at Xochicalco. A unique and common architectural complex found among many Mesoamerican sites are E-Groups, which are aligned so as to serve as astronomical observatories. The name of this complex is based on Uaxactun’s “Group E,” the first known observatory in the Maya area. Perhaps the earliest observatory documented in Mesoamerica is that of the Monte Alto culture. This complex consisted of three plain stelae and a temple oriented with respect to the Pleiades.

Symbolism of space and time

The Avenue of the Dead in Teotihuacan, an example of a Mesoamerican settlement planned according to concepts of directionality

It has been argued that among Mesoamerican societies the concepts of space and time are associated with the four cardinal compass points and linked together by the calendar.[35] Dates or events were always tied to a compass direction, and the calendar specified the symbolic geographical characteristic peculiar to that period. Resulting from the significance held by the cardinal directions, many Mesoamerican architectural features, if not entire settlements, were planned and oriented with respect to directionality.

In Maya cosmology, each cardinal point was assigned a specific color and a specific jaguar deity (Bacab). They are as follows:

- Hobnil, Bacab of the East, associated with the color red and the Kan years

- Can Tzicnal, Bacab of the North, assigned the color white and the Muluc years

- 'Zac Cimi, Bacab of the West, associated with the color black and the Ix years

- Hozanek, Bacab of the South, associated with the color yellow and the Cauac years.

Among the Aztec, the name of each day was associated with a cardinal point (thus conferring symbolic significance), and each cardinal direction was associated with a group of symbols. Below are the symbols and concepts associated with each direction:

- East: crocodile, the serpent, water, cane, and movement. The East was linked to the world priests and associated with vegetative fertility, or, in other words, tropical exuberance.

- North: wind, death, the dog, the jaguar, and flint (or chert). The north contrasts with the east in that it is conceptualized as dry, cold, and oppressive. It is considered to be the nocturnal part of the universe and includes the dwellings of the dead. The dog (xoloitzcuintle) has a very specific meaning, as it accompanies the deceased during the trip to the lands of the dead and helps them cross the river of death that leads into nothingness. (See also Dogs in Mesoamerican folklore and myth).

- West: the house, the deer, the monkey, the eagle, and rain. The west was associated with the cycles of vegetation, specifically the temperate high plains that experience light rains and the change of seasons.

- South: rabbit, the lizard, dried herbs, the buzzard, and flowers. It is related on the one hand to the luminous Sun and the noon heat, and on the other with rain filled with alcoholic drink. The rabbit, the principal symbol of the west, was associated with farmers and with pulque.

Political and religious art

Art with ideological and political meaning: depiction of an Aztec tzompantli (skull-rack) from the Ramirez Codex

Mesoamerican artistic expression was conditioned by ideology and generally focused on themes of religion and/or sociopolitical power. This is largely based on the fact that most works that survived the Spanish conquest were public monuments. These monuments were typically erected by rulers who sought to visually legitimize their sociocultural and political position; by doing so, they intertwined their lineage, personal attributes and achievements, and legacy with religious concepts. As such, these monuments were specifically designed for public display and took many forms, including stele, sculpture, architectural reliefs, and other types of architectural elements (e.g., roofcombs). Other themes expressed include tracking time, glorifying the city, and veneration of the gods – all of which were tied to explicitly aggrandizing the abilities and the reign of the ruler who commissioned the artwork.