Suffrage universel dédié à Ledru-Rollin, Frédéric Sorrieu, 1850

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to vote is called active suffrage, as distinct from passive suffrage, which is the right to stand for election. The combination of active and passive suffrage is sometimes called full suffrage.

Suffrage is often conceived in terms of elections for representatives. However, suffrage applies equally to referenda and initiatives. Suffrage describes not only the legal right to vote, but also the practical question of whether a question will be put to a vote. The utility of suffrage is reduced when important questions are decided unilaterally without extensive, conscientious, full disclosure and public review.

In most democracies, eligible voters can vote in elections of representatives. Voting on issues by referendum may also be available. For example, in Switzerland this is permitted at all levels of government. In the United States, some states such as California and Washington have exercised their shared sovereignty to offer citizens the opportunity to write, propose, and vote on referendums and initiatives; other states and the federal government have not. Referendums in the United Kingdom are rare.

Suffrage is granted to qualifying citizens once they have reached the voting age. What constitutes a qualifying citizen depends on the government's decision. Resident non-citizens can vote in some countries, which may be restricted to citizens of closely linked countries (e.g., Commonwealth citizens and European Union citizens) or to certain offices or questions.

Etymology

The word suffrage comes from Latin suffragium, meaning "vote", "political support", and the right to vote. The etymology of the Latin word is uncertain, with some sources citing Latin suffragari "lend support, vote for someone", from sub "under" + fragor "crash, din, shouts (as of approval)", related to frangere "to break" (related to fraction and fractious "quarrelsome"). Other sources say that attempts to connect suffragium with fragor cannot be taken seriously. Some etymologists think the word may be related to suffrago and may have originally meant an ankle bone or knuckle bone.Types

Universal suffrage

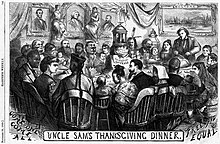

Universal suffrage consists of the right to vote without restriction due to sex, race, social status, education level, or wealth. It typically does not extend the right to vote to all residents of a region; distinctions are frequently made in regard to citizenship, age, and occasionally mental capacity or criminal convictions.The short-lived Corsican Republic (1755–1769) was the first country to grant limited universal suffrage to all citizens over the age of 25. This was followed by other experiments in the Paris Commune of 1871 and the island republic of Franceville (1889). The 1840 constitution of the Kingdom of Hawai'i granted universal suffrage to all male and female adults. In 1893, when the Kingdom of Hawai'i was overthrown in a coup, New Zealand became the only independent country to practice universal (active) suffrage, and the Freedom in the World index lists New Zealand as the only free country in the world in 1893.

Women's suffrage

German election poster from 1919: Equal rights – equal duties!

Women's suffrage is, by definition, the right of women to vote. This was the goal of the suffragists, who believed in using legal means and the suffragettes, who used extremist measures. Short-lived suffrage equity was drafted into provisions of the State of New Jersey's first, 1776 Constitution, which extended the Right to Vote to unwed female landholders & black land owners.

"IV. That all inhabitants of this Colony, of full age, who are worth fifty pounds proclamation money, clear estate in the same, and have resided within the county in which they claim a vote for twelve months immediately preceding the election, shall be entitled to vote for Representatives in Council and Assembly; and also for all other public officers, that shall be elected by the people of the county at large." New Jersey 1776However, the document did not specify an Amendment procedure, and the provision was subsequently replaced in 1844 by the adoption of the succeeding constitution, which reverted to "all white male" suffrage restrictions.

Although the Kingdom of Hawai'i granted female suffrage in 1840, the right was rescinded in 1852. Limited voting rights were gained by some women in Sweden, Britain, and some western U.S. states in the 1860s. In 1893, the British colony of New Zealand became the first self-governing nation to extend the right to vote to all adult women. In 1894 the women of South Australia achieved the right to both vote and stand for Parliament. The autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland in the Russian Empire was the first nation to allow all women to both vote and run for parliament.

Equal suffrage

Equal suffrage is sometimes confused with Universal suffrage, although the meaning of the former is the removal of graded votes, wherein a voter could possess a number of votes in accordance with income, wealth or social status.Census suffrage

Also known as "censitary suffrage", the opposite of equal suffrage, meaning that the votes cast by those eligible to vote are not equal, but are weighed differently according to the person's rank in the census (e.g., people with higher education have more votes than those with lower education, or a stockholder in a company with more shares has more votes than someone with fewer shares). Suffrage may therefore be limited, but can still be universal.Compulsory suffrage

Where compulsory suffrage exists, those who are eligible to vote are required by law to do so. Thirty-two countries currently practise this form of suffrage.Business vote

In local government in England and some of its ex-colonies, businesses formerly had, and in some places still have, a vote in the urban area in which they paid rates. This is an extension of the historical property-based franchise from natural persons to other legal persons.In the United Kingdom, the Corporation of the City of London has retained and even expanded business vote, following the passing of the City of London (Ward Elections) Act 2002. This has given business interests within the City of London, which is a major financial centre with few residents, the opportunity to apply the accumulated wealth of the corporation to the development of an effective lobby for UK policies. This includes having the City Remembrancer, financed by the City's Cash, as a Parliamentary agent, provided with a special seat in the House of Commons located in the under-gallery facing the Speaker's chair. In a leaked document from 2012, an official report concerning the City's Cash revealed that the aim of major occasions such as set-piece sumptious banquets featuring national politicians was "to increase the emphasis on complementing hospitality with business meetings consistent with the City corporation's role in supporting the City as a financial centre".

The first issue taken up by the Northern Ireland civil rights movement was the business vote, abolished in 1968.

In the Republic of Ireland, commercial ratepayers can vote in local plebiscites, for changing the name of the locality or street, or delimiting a business improvement district. From 1930 to 1935, 5 of 35 members of Dublin City Council were "commercial members".

In cities in most Australian states, voting is optional for businesses but compulsory for individuals.

Forms of exclusion from suffrage

Religion

In the aftermath of the Reformation it was common in European countries for people of disfavored religious denominations to be denied civil and political rights, often including the right to vote, to stand for election or to sit in parliament. In Great Britain and Ireland, Roman Catholics were denied the right to vote from 1728 to 1793, and the right to sit in parliament until 1829. The anti-Catholic policy was justified on the grounds that the loyalty of Catholics supposedly lay with the Pope rather than the national monarch.In England and Ireland, several Acts practically disenfranchised non-Anglicans or non-Protestants by imposing an oath before admission to vote or to stand for office. The 1672 and 1678 Test Acts forbade non-Anglicans to hold public offices, and the 1727 Disenfranchising Act took away Catholics' voting rights in Ireland, which were restored only in 1788. Jews could not even be naturalized. An attempt was made to change this situation, but the Jewish Naturalization Act 1753 provoked such reactions that it was repealed the following year. Nonconformists (Methodists and Presbyterians) were only allowed to run for election to the British House of Commons starting in 1828, Catholics in 1829 (following the Catholic Relief Act 1829, which extended the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791), and Jews in 1858 (with the Emancipation of the Jews in England). Benjamin Disraeli could only begin his political career in 1837 because he had been converted to Anglicanism at the age of 12.

In several states in the U.S. after the Declaration of Independence, Jews, Quakers or Catholics were denied voting rights and/or forbidden to run for office. The Delaware Constitution of 1776 stated that "Every person who shall be chosen a member of either house, or appointed to any office or place of trust, before taking his seat, or entering upon the execution of his office, shall (…) also make and subscribe the following declaration, to wit: I, A B. do profess faith in God the Father, and in Jesus Christ His only Son, and in the Holy Ghost, one God, blessed for evermore; and I do acknowledge the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by divine inspiration." This was repealed by article I, section 2 of the 1792 Constitution: "No religious test shall be required as a qualification to any office, or public trust, under this State". The 1778 Constitution of the State of South Carolina stated that "No person shall be eligible to sit in the house of representatives unless he be of the Protestant religion", the 1777 Constitution of the State of Georgia (art. VI) that "The representatives shall be chosen out of the residents in each county (…) and they shall be of the Protestent (sic) religion". In Maryland, voting rights and eligibility were extended to Jews in 1828.

In Canada, several religious groups (Mennonites, Hutterites, Doukhobors) were disenfranchised by the wartime Elections Act of 1917, mainly because they opposed military service. This disenfranchisement ended with the closure of the First World War, but was renewed for Doukhobors from 1934 (via the Dominion Elections Act) to 1955.

The first Constitution of modern Romania in 1866 provided in article 7 that only Christians could become Romanian citizens. Jews native to Romania were declared stateless persons. In 1879, under pressure from the Berlin Peace Conference, this article was amended, granting non-Christians the right to become Romanian citizens, but naturalization was granted on a case-by-case basis and was subject to Parliamentary approval. An application took over ten years to process. Only in 1923 was a new constitution adopted, whose article 133 extended Romanian citizenship to all Jewish residents and equality of rights to all Romanian citizens.

In the Republic of Maldives, only Muslim citizens have voting rights and are eligible for parliamentary elections.

Wealth, tax class, social class

Until the nineteenth century, many Western proto-democracies had property qualifications in their electoral laws; e.g. only landowners could vote (because the only tax for such countries was the property tax), or the voting rights were weighted according to the amount of taxes paid (as in the Prussian three-class franchise). Most countries abolished the property qualification for national elections in the late nineteenth century, but retained it for local government elections for several decades. Today these laws have largely been abolished, although the homeless may not be able to register because they lack regular addresses.In the United Kingdom, until the House of Lords Act 1999, peers who were members of the House of Lords were excluded from voting for the House of Commons because they were not commoners. Although there is nothing to prevent the monarch from voting it is considered unconstitutional for the monarch to vote in an election.

Knowledge

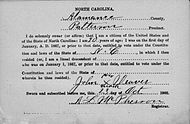

Sometimes the right to vote has been limited to people who had achieved a certain level of education or passed a certain test, e.g. "literacy tests" were previously implemented in some U.S. states. Under the 1961 constitution of Rhodesia, voting on the "A" roll, which elected up to 50 of the 65 members of parliament, was restricted based on education requirements, which in practice led to an overwhelming white vote. Voting on the "B" roll had universal suffrage, but only appointed 15 members of parliament.Race

Various countries, usually countries with a dominant race within a wider population, have historically denied the vote to people of particular races, or to all but the dominant race. This has been achieved in a number of ways:- Official – laws and regulations passed specifically disenfranchising people of particular races (for example, the Antebellum United States, Boer republics, pre-apartheid and apartheid South Africa, or many colonial political systems, who provided suffrage only for white settlers and some privileged non-white groups). Canada and Australia denied suffrage for their indigenous populations until the 1960s.

- Indirect – nothing in law specifically prevents anyone from voting on account of their race, but other laws or regulations are used to exclude people of a particular race. In southern states of the United States of America before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, poll taxes, literacy and other tests were used to disenfranchise African-Americans. Property qualifications have tended to disenfranchise a minority race, particularly if tribally owned land is not allowed to be taken into consideration. In some cases this was an unintended (but usually welcome) consequence. Many African colonies after World War II until decolonization had tough education and property qualifications which practically gave meaningful representation only for rich European minorities.

- Unofficial – nothing in law prevents anyone from voting on account of their race, but people of particular races are intimidated or otherwise prevented from exercising this right. This was a common tactic employed by white Southerners against Freedmen during the Reconstruction Era and the following period before more formal methods of disenfranchisement became entrenched.

Age

All modern democracies require voters to meet age qualifications to vote. Worldwide voting ages are not consistent, differing between countries and even within countries, though the range usually varies between 16 and 21 years. Demeny voting would extend voting rights to everyone including children regardless of age. The movement to lower the voting age is known as the Youth rights movement.Criminality

Many countries restrict the voting rights of convicted criminals. Some countries, and some U.S. states, also deny the right to vote to those convicted of serious crimes even after they are released from prison. In some cases (e.g. the felony disenfranchisement laws found in many U.S. states) the denial of the right to vote is automatic upon a felony conviction; in other cases (e.g. France and Germany) deprivation of the vote is meted out separately, and often limited to perpetrators of specific crimes such as those against the electoral system or corruption of public officials. In the Republic of Ireland, prisoners are allowed the right to vote, following the Hirst v UK (No2) ruling, which was granted in 2006. Canada allowed only prisoners serving a term of less than 2 years the right to vote, but this was found to be unconstitutional in 2002 by the Supreme Court of Canada in Sauvé v. Canada (Chief Electoral Officer), and all prisoners have been allowed to vote as of the 2004 Canadian federal election.Residency

Under certain electoral systems elections are held within subnational jurisdictions, thus preventing persons from voting who would otherwise be eligible on the basis that they do not reside within such a jurisdiction, or because they live in an area that cannot participate. In the United States, residents of Washington, D.C. receive no voting representation in Congress, although they do have full representation in presidential elections, based on the Twenty-third Amendment to the United States Constitution adopted in 1961. Residents of Puerto Rico enjoy neither.Sometimes citizens become ineligible to vote because they are no longer resident in their country of citizenship. For example, Australian citizens who have been outside Australia for more than one and fewer than six years may excuse themselves from the requirement to vote in Australian elections while they remain outside Australia (voting in Australia is compulsory for resident citizens). Danish citizens that reside permanently outside Denmark lose their right to vote.

In some cases, a certain period of residence in a locality may required for the right to vote in that location. For example, in the United Kingdom up to 2001, each 15 February a new electoral register came into effect, based on registration as of the previous 10 October, with the effect of limiting voting to those resident five to seventeen months earlier depending on the timing of the election.

Nationality

In most countries, suffrage is limited to citizens and, in many cases, permanent residents of that country. However, some members of supra-national organisations such as the Commonwealth of Nations and the European Union have granted voting rights to citizens of all countries within that organisation. Until the mid-twentieth century, many Commonwealth countries gave the vote to all British citizens within the country, regardless of whether they were normally resident there. In most cases this was because there was no distinction between British and local citizenship. Several countries qualified this with restrictions preventing non-white British citizens such as Indians and British Africans from voting. Under European Union law, citizens of European Union countries can vote in each other's local and European Parliament elections on the same basis as citizens of the country in question, but usually not in national elections.Naturalization

In some countries, naturalized citizens do not have the right to vote or to be a candidate, either permanently or for a determined period.Article 5 of the 1831 Belgian Constitution made a difference between ordinary naturalization, and grande naturalisation. Only (former) foreigners who had been granted grande naturalisation were entitled to vote, be a candidate for parliamentary elections, or be appointed minister. However, ordinary naturalized citizens could vote for municipal elections. Ordinary naturalized citizens and citizens who had acquired Belgian nationality through marriage could vote, but not run as candidates for parliamentary elections in 1976. The concepts of ordinary and grande naturalization were suppressed from the Constitution in 1991.

In France, the 1889 Nationality Law barred those who had acquired the French nationality by naturalization or marriage from voting, and from eligibility and access to several public jobs. In 1938 the delay was reduced to five years. These instances of discrimination, as well as others against naturalized citizens, were gradually abolished in 1973 (9 January 1973 law) and 1983.

In Morocco, a former French protectorate, and in Guinea, a former French colony, naturalized citizens are prohibited from voting for five years following their naturalization.

In the Federated States of Micronesia, one must be a Micronesian citizen for at least 15 years to run for parliament.

In Nicaragua, Peru and the Philippines, only citizens by birth are eligible for being elected to the national legislature; naturalized citizens enjoy only voting rights.

In Uruguay, naturalized citizens have the right of eligibility to the parliament after five years.

In the United States, the President and Vice President must be natural-born citizens. All other governmental offices may be held by any citizen, although citizens may only run for Congress after an extended period of citizenship (seven years for the House of Representatives and nine for the Senate).

Function

In France, an 1872 law, rescinded only by a 1945 decree, prohibited all army personnel from voting.In Ireland, police (the Garda Síochána and, before 1925, the Dublin Metropolitan Police) were barred from voting in national elections, though not local elections, from 1923 to 1960.

The 1876 Constitution of Texas (article VI, section 1) stated that "The following classes of persons shall not be allowed to vote in this State, to wit: (…) Fifth—All soldiers, marines and seamen, employed in the service of the army or navy of the United States."

In many countries with a presidential system of government a person is forbidden to be a legislator and an official of the executive branch at the same time. Such provisions are found, for example, in Article I of the U.S. Constitution.

History around the world

In 1840, the Kingdom of Hawai'i adopted full suffrage to all adults, including women, but in 1852 rescinded female voting. In 1902 the Commonwealth Franchise Act enabled women to vote federally in Australia and in the state of New South Wales. This legislation also allowed women to run for government, making Australia the first in the world to allow this. In 1906 Finland became the next nation in the world to give all adult citizens full suffrage, in other words the right to vote and to run for office. New Zealand granted all adult citizens the right to vote (in 1893), but women did not get the right to run for the New Zealand legislature until 1919.Australia

- 1855 — South Australia is first colony to allow all male suffrage to British subjects (later extended to Indigenous males) over the age of 21.

- 1894 – South Australian women eligible to vote.

- 1896 — Tasmania becomes last colony to allow all male suffrage.

- 1899 – Western Australian women eligible to vote.

- 1902 – The Commonwealth Franchise Act enables women to vote federally and in the state of New South Wales. This legislation also allows women to run for government, making Australia the first democratic state in the world to allow this.

- 1921 – Edith Cowan is elected to the West Australian Legislative Assembly as member for West Perth, the first woman elected to any Australian Parliament.

- 1962 – Aboriginal peoples guaranteed the right to vote in Commonwealth elections.

Brazil

- 1824 – The first Brazilian constitution allows free men over the age of 25 to vote, but there are income restrictions. The House of Deputies' representatives are chosen via electoral colleges.

- 1881 – The Saraiva Law implements direct voting, but there are income restrictions. Women and slaves do not have the right to vote.

- 1932 – Voting becomes obligatory for all adults over 21 years of age, unlimited by gender or income.

- 1955 – Adoption of standardized voting ballots and identification requirements to mitigate frauds.

- 1964 – Military regime established. From then on, presidents were elected by members of the congress, chosen by regular vote.

- 1989 – Reestablishment of universal suffrage for all citizens over 16 years of age. People considered illiterate are not obliged to vote, nor are people younger than 18 and older than 70 years of age. People under the obligation rule shall file a document to justify their absence should they not vote.

- 2000 – Brazil becomes the first country to fully adopt electronic ballots in their voting process.

Canada

- 1871 – One of the first acts of the new Province of British Columbia strips the franchise from First Nations, and ensures Chinese and Japanese people are prevented from voting.

- 1916 – Manitoba becomes the first province in which women have the right to vote in provincial elections.

- 1917 – Wartime Elections Act gives voting rights to women with relatives fighting overseas. Voting rights are stripped from all "enemy aliens" (those born in enemy countries who arrived in Canada after 1902; see also Ukrainian Canadian internment). Military Voters Act gives the vote to all soldiers, even non-citizens, (with the exception of Indian and Metis veterans) and to females serving as nurses or clerks for the armed forces, but the votes are not for specific candidates but simply for or against the government.

- 1918 – Women gain full voting rights in federal elections.

- 1919 – Women gain the right to run for federal office.

- 1940 – Quebec becomes the last province where women's right to vote is recognized.

- 1947 – Racial exclusions against Chinese and Indo-Canadians lifted.

- 1948 – Racial exclusions against Japanese Canadians lifted.

- 1955 – Religious exclusions are removed from election laws.

- 1960 – Right to vote is extended unconditionally to First Nations peoples. (Previously they could vote only by giving up their status as First Nations people.)

- 1960 – Right to vote in advance is extended to all electors willing to swear they would be absent on election day.

- 1965 – First Nations people granted the right to vote in Alberta provincial elections, starting with the Alberta general election, 1967.

- 1969 – First Nations people granted the right to vote in Quebec provincial elections, starting with the Quebec general election, 1970.

- 1970 – Voting age lowered from 21 to 18.

- 1982 – Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees all adult citizens the right to vote.

- 1988 – Supreme Court of Canada rules mentally ill patients have the right to vote.

- 1993 – Any elector can vote in advance.

- 2000 – Legislation is introduced making it easier for people of no fixed address to vote.

- 2002 – Prisoners given the right to vote in the riding (voting district) where they were convicted. All adult Canadians except the Chief and Deputy Electoral Officers can now vote in Canada.

European Union

The European Union has given the right to vote in municipal elections to the citizen of another EU country by the Council Directive 94/80/EG from the 19th of December 1994.Finland

- 1906 – Full suffrage for all citizens adults aged 24 or older at beginning of voting year.

- 1921 – Suppression of property-based number of votes on municipal level; equal vote for everybody.

- 1944 – Voting age lowered to 21 years.

- 1969 – Voting age lowered to 20 years.

- 1972 – Voting age lowered to 18 years.

- 1981 – Voting and eligibility rights were granted to Nordic Passport Union country citizens without residency condition for municipal elections.

- 1991 – Voting and eligibility rights were extended to all foreign residents in 1991 with a two-year residency condition for municipal elections.

- 1995 – Residency requirement abolished for EU residents, in conformity with European legislation (Law 365/95, confirmed by Electoral Law 714/1998).

- 1996 – Voting age lowered to 18 years at date of voting.

- 2000 – Section 14, al. 2 of the 2000 Constitution of Finland states that "Every Finnish citizen and every foreigner permanently resident in Finland, having attained eighteen years of age, has the right to vote in municipal elections and municipal referendums, as provided by an Act. Provisions on the right to otherwise participate in municipal government are laid down by an Act."

France

- 11 August 1792 : Introduction of universal suffrage (men only)

- 1795 : Universal suffrage for men is replaced with indirect Census suffrage

- 13 December 1799: The French Consulate re-establishes male universal suffrage for men over 21 years old resident in France. The electors must select one tenth amongst themselves to “communal lists”, which in turn elect one tenth to “departmental lists”, which then elect one tenth to the “national list”. The senate then chose the representatives from that list.

- In 1815: the restoration of the monarchy leads to the abolition of male universal suffrage, in favour of the census suffrage with an increased minimum age (increase to 30 years old initially but then reduced to 25)

- In 1848: The Second Republic re-established male universal suffrage for all Frenchmen aged over 21. The number eligible to vote increased from 246,000 to over 9 million.

- In 1850 (31 May): The number of people eligible to vote is reduced by 30% by excluding criminals and the homeless.

- Napoleon III calls a referendum in 1851 (21 December), all men aged 21 and over are allowed to vote. Male universal suffrage is established thereafter.

- As of 21 April 1944 the franchise is extended to women over 21

- On 5 July 1974 the minimum age to vote is reduced to 18 years old.

Kingdom of Hawai'i

In 1840, the king of Hawai'i issued a constitution that granted universal suffrage, both for females and males, but later amendments added restrictions, as the influence of Caucasian settlers increased:- 1852 - Women lost the right to vote, and the minimum voting age was specified as 20.

- 1864 - Voting was restricted on the basis of new qualifications—literacy and either a certain level of income or property ownership.

- 1887 - Citizens of Hawai'i with Asian descent were disqualified. There was an increase in the minimum value of income or owned property.

Hong Kong

Minimum age to vote was reduced from 21 to 18 years in 1995. The Basic Law, the constitution of the territory since 1997, stipulates that all permanent residents (a status conferred by birth or by seven years of residence) have the right to vote. The right of permanent residents who have right of abode in other countries to stand in election is, however, restricted to 12 functional constituencies by the Legislative Council Ordinance of 1997.The right to vote and the right to stand in elections are not equal. Fewer than 250,000 of the electorate are eligible to run in the 30 functional constituencies, of which 23 are elected by fewer than 80,000 of the electorate, and in the 2008 Legislative Council election 14 members were elected unopposed from these functional constituencies. The size of the electorates of some constituencies is fewer than 200. Only persons who can demonstrate a connection to the sector are eligible to run in a functional constituency.

The Legislative Council (Amendment) Bill 2012, if passed, amends the Legislative Council Ordinance to restrict the right to stand in Legislative Council by-elections in geographical constituencies and the District Council (Second) functional constituency. In addition to those persons who are mentally disabled, bankrupt, or imprisoned, members who resign their seats will not have the right to stand for six months' time from their resignation. The bill is currently passing through the committee stage.

India

Since the very first Indian general election held in 1951–52, universal suffrage for all adult citizens aged 21 or older was established under Article 326 of the Constitution of India. The minimum voting age was reduced to 18 years by the 61st Amendment, effective 28 March 1989.Ireland

Isle of Man

- 1866 - The House of Keys Election Act makes the House of Keys an elected body. The vote is given to men over the age of 21 who own property worth at least £8 a year or rent property worth at least £12 a year. Candidates must be male, with real estate of an annual value of £100, or of £50 along with a personal estate producing an annual income of £100.

- 1881 - The House of Keys Election Act is amended so that the property qualification is reduced to a net annual value of not less than £4. Most significantly, the Act is also amended to extend the franchise to unmarried women and widows over the age of 21 who own property, making the Isle of Man the first place to give some women the vote in a national election. The property qualification for candidates is modified to allow the alternative of personal property producing a year income of £150.

- 1892 - The franchise is extended to unmarried women and widows over the age of 21 who rent property worth a net annual value of at least £4, as well as to male lodgers. The property qualification for candidates is removed.

- 1903 - A residency qualification is introduced in addition to the property qualification for voters. The time between elections is reduced from 7 to 5 years.

- 1919 - Universal adult suffrage based on residency is introduced: all male and female residents over the age of 21 may vote. The entire electorate (with the exception of clergy and holders of office of profit) becomes eligible to stand for election.

- 1970 - Voting age lowered to 18.

- 2006 - Voting age lowered to 16. The age of eligibility for candidates remains at 18.

Italy

The Supreme Court states that "the rules derogating from the passive electoral law must be strictly interpreted".Japan

- 1947 – Universal Suffrage instituted with the establishment of Post-war Constitution.

New Zealand

- 1853 – British government passes the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852, granting limited self-rule, including a bicameral parliament, to the colony. The vote was limited to male British subjects aged 21 or over who owned or rented sufficient property and were not imprisoned for a serious offence. Communally owned land was excluded from the property qualification, thus disenfranchising most Māori (indigenous) men.

- 1860 – Franchise extended to holders of miner's licenses who met all voting qualifications except that of property.

- 1867 – Māori seats established, giving Māori four reserved seats in the lower house. There was no property qualification; thus Māori men gained universal suffrage before other New Zealanders. The number of seats did not reflect the size of the Māori population, but Māori men who met the property requirement for general electorates were able to vote in them or in the Māori electorates but not both.

- 1879 – Property requirement abolished.

- 1893 – Women won equal voting rights with men, making New Zealand the first nation in the world to allow adult women to vote.

- 1969 – Voting age lowered to 20.

- 1974 – Voting age lowered to 18.

- 1975 – Franchise extended to permanent residents of New Zealand, regardless of whether they have citizenship.

- 1996 – Number of Māori seats increased to reflect Māori population.

- 2010 – Prisoners imprisoned for one year or more denied voting rights while serving the sentence.

Poland

- 1918 – In its first days of independence in 1918, after 123 years of partition, voting rights were granted to both men and women. Eight women were elected to the Sejm in 1919.

- 1952 – Voting age lowered to 18.

South Africa

- 1910 — The Union of South Africa is established by the South Africa Act 1909. The House of Assembly is elected by first-past-the-post voting in single-member constituencies. The franchise qualifications are the same as those previously existing for elections of the legislatures of the colonies that comprised the Union. In the Transvaal and the Orange Free State the franchise is limited to white men. In Natal the franchise is limited to men meeting property and literacy qualifications; it was theoretically colour-blind but in practise nearly all non-white men were excluded. The traditional "Cape Qualified Franchise" of the Cape Province is limited to men meeting property and literacy qualifications and is colour-blind; nonetheless 85% of voters are white. The rights of non-white voters in the Cape Province are protected by an entrenched clause in the South Africa Act requiring a two-thirds vote in a joint sitting of both Houses of Parliament.

- 1930 — The Women's Enfranchisement Act, 1930 extends the right to vote to all white women over the age of 21.

- 1931 — The Franchise Laws Amendment Act, 1931 removes the property and literacy qualifications for all white men over the age of 21, but they are retained for non-white voters.

- 1936 — The Representation of Natives Act, 1936 removes black voters in the Cape Province from the common voters' roll and instead allows them to elect three "Native Representative Members" to the House of Assembly. Four Senators are to be indirectly elected by chiefs and local authorities to represent black South Africans throughout the country. The act is passed with the necessary two-thirds majority in a joint sitting.

- 1951 — The Separate Representation of Voters Act, 1951 is passed by Parliament by an ordinary majority in separate sittings. It purports to remove coloured voters in the Cape Province from the common voters' roll and instead allow them to elect four "Coloured Representative Members" to the House of Assembly.

- 1952 — In Harris v Minister of the Interior the Separate Representation of Voters Act is annulled by the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court because it was not passed with the necessary two-thirds majority in a joint sitting. Parliament passes the High Court of Parliament Act, 1952, purporting to allow it to reverse this decision, but the Appellate Division annuls it as well.

- 1956 — By packing the Senate and the Appellate Division, the government passes the South Africa Act Amendment Act, 1956, reversing the annulment of the Separate Representation of Voters Act and giving it the force of law.

- 1958 — The Electoral Law Amendment Act, 1958 reduces the voting age for white voters from 21 to 18.

- 1959 — The Promotion of Bantu Self-government Act, 1959 repeals the Representation of Natives Act, removing all representation of black people in Parliament.

- 1968 — The Separate Representation of Voters Amendment Act, 1968 repeals the Separate Representation of Voters Act, removing all representation of coloured people in Parliament.

- 1969 — The first election of the Coloured Persons Representative Council (CPRC), which has limited legislative powers, is held. Every Coloured citizen over the age of 21 can vote for its members, in first-past-the-post elections in single-member constituencies.

- 1978 — The voting age for the CPRC is reduced from 21 to 18.

- 1981 — The first election of the South African Indian Council (SAIC), which has limited legislative powers, is held. Every Indian South African citizen over the age of 18 can vote for its members, in first-past-the-post elections in single-member constituencies.

- 1984 — The Constitution of 1983 establishes the Tricameral Parliament. Two new Houses of Parliament are created, the House of Representatives to represent coloured citizens and the House of Delegates to represent Indian citizens. Every coloured and Indian citizen over the age of 18 can vote in elections for the relevant house. As with the House of Assembly, the members are elected by first-past-the-post voting in single-member constituencies. The CPRC and SAIC are abolished.

- 1994 — With the end of apartheid, the Interim Constitution of 1993 abolishes the Tricameral Parliament and all racial discrimination in voting rights. A new National Assembly is created, and every South African citizen over the age of 18 has the right to vote for the assembly. The right to vote is also extended to long term residents. It is estimated the 500 000 foreign nationals voted in the 1994 national and provincial elections. Elections of the assembly are based on party-list proportional representation. The right to vote is enshrined in the Bill of Rights.

- 1999 — In August and Another v Electoral Commission and Others the Constitutional Court rules that prisoners cannot be denied the right to vote without a law that explicitly does so.

- 2003 — The Electoral Laws Amendment Act, 2003 purports to prohibit convicted prisoners from voting.

- 2004 — In Minister of Home Affairs v NICRO and Others the Constitutional Court rules that prisoners cannot be denied the right to vote, and invalidates the laws that do so.

- 2009 — In Richter v Minister for Home Affairs and Others the Constitutional Court rules that South African citizens outside the country cannot be denied the right to vote.

Sweden

- 1809 — New constitution adopted and separation of powers outlined in the Instrument of Government.

- 1810 — The Riksdag Act, setting out the procedures of functioning of the Riksdag, is introduced.

- 1862 — Under the municipal laws of 1862, some women were entitled to vote in local elections.

- 1865 — Parliament of Four Estates abolished and replaced by a bicameral legislature. The members of the First Chamber were elected indirectly by the county councils and the municipal assemblies in the larger towns and cities.

- 1909 — All men who had done their military service and who paid tax were granted suffrage.

- 1918 — Universal, and equal suffrage were introduced for local elections.

- 1919 — Universal, equal, and women's suffrage granted for general elections.

- 1921 — First general election with universal, equal, and women's suffrage enacted, although some groups were still unable to vote.

- 1922 — Requirement that men had to have completed national military service to be able to vote abolished.

- 1937 — Interns in prisons and institutions granted suffrage.

- 1945 — Individuals who had gone into bankruptcy or were dependent on welfare granted suffrage.

- 1970 — Indirectly elected upper chamber dismantled.

- 1974 — Instrument of Government stopped being enforced.

- 1989 — The final limitations on suffrage abolished along with the Riksdag's decision to abolish the 'declaration of legal incompetency'.

United Kingdom

From 1265, a few percent of the adult male population in the Kingdom of England (of which Wales was a full and equal member from 1542) were able to vote in parliamentary elections that occurred at irregular intervals to the Parliament of England. The franchise for the Parliament of Scotland developed separately. King Henry VI of England established in 1432 that only owners of property worth at least forty shillings, a significant sum, were entitled to vote in an English county. The franchise was restricted to males by custom rather than statute. Changes were made to the details of the system, but there was no major reform until the Reform Act 1832. A series of Reform Acts and Representation of the People Acts followed. In 1918, all men over 21 and some women over 30 won the right to vote, and in 1928 all women over 21 won the right to vote resulting in universal suffrage.- Reform Act 1832 – extended voting rights to adult males who rented propertied land of a certain value, so allowing 1 in 7 males in the UK voting rights.

- Reform Act 1867 – extended the franchise to men in urban areas who met a property qualification, so increasing male suffrage.

- Representation of the People Act 1884 – addressed imbalances between the boroughs and the countryside; this brought the voting population to 5,500,000, although 40% of males were still disenfranchised because of the property qualification.

- Between 1885 and 1918 moves were made by the women's suffrage movement to ensure votes for women. However, the duration of the First World War stopped this reform movement.

- Representation of the People Act 1918 – the consequences of World War I persuaded the government to expand the right to vote, not only for the many men who fought in the war who were disenfranchised, but also for the women who worked in factories, agriculture and elsewhere as part of the war effort, often substituting for enlisted men and including dangerous work such as in munitions factories. All men aged 21 and over were given the right to vote. Property restrictions for voting were lifted for men. Votes were given to 40% of women, with property restrictions and limited to those over 30 years old. This increased the electorate from 7.7 million to 21.4 million with women making up 8.5 million of the electorate. Seven percent of the electorate had more than one vote. The first election with this system was the 1918 general election.

- Representation of the People Act 1928 – equal suffrage for women and men, with voting possible at 21 with no property restrictions.

- Representation of the People Act 1948 – the act was passed to prevent plural voting.

- Representation of the People Act 1969 – extension of suffrage to those 18 and older.

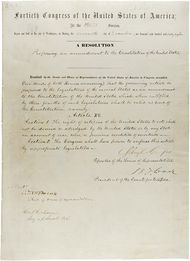

United States

The Constitution did not originally define who was eligible to vote, allowing each state to decide this status. In the early history of the U.S., most states allowed only white male adult property owners to vote (about 6% of the population). By 1856 property ownership requirements were eliminated in all states, giving suffrage to most adult white males. However, tax-paying requirements remained in five states until 1860 and in two states until the 20th century. After the Civil War, five amendments to the Constitution were expressly addressed to the "right to vote"; these amendments limit the basis upon which the right to vote in any U.S. state or other jurisdiction may be abridged or denied.- 15th Amendment (1870): "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

- 19th Amendment (1920): "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

- 23rd Amendment (1961): provides that residents of the District of Columbia can vote for the President and Vice President.

- 24th Amendment (1964): "The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, for electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax."

- 26th Amendment (1971): "The right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of age."