Efforts are made to preserve the natural characteristics of Hopetoun Falls, Australia, without affecting visitors' access.

Conservation biology is the management of nature and of Earth's biodiversity with the aim of protecting species, their habitats, and ecosystems from excessive rates of extinction and the erosion of biotic interactions. It is an interdisciplinary subject drawing on natural and social sciences, and the practice of natural resource management.

The conservation ethic is based on the findings of conservation biology.

Origins

The term conservation biology and its conception as a new field originated with the convening of "The First International Conference on Research in Conservation Biology" held at the University of California, San Diego in La Jolla, California in 1978 led by American biologists Bruce A. Wilcox and Michael E. Soulé with a group of leading university and zoo researchers and conservationists including Kurt Benirschke, Sir Otto Frankel, Thomas Lovejoy, and Jared Diamond. The meeting was prompted by the concern over tropical deforestation, disappearing species, eroding genetic diversity within species. The conference and proceedings that resulted sought to initiate the bridging of a gap between theory in ecology and evolutionary genetics on the one hand and conservation policy and practice on the other. Conservation biology and the concept of biological diversity (biodiversity) emerged together, helping crystallize the modern era of conservation science and policy. The inherent multidisciplinary basis for conservation biology has led to new subdisciplines including conservation social science, conservation behavior and conservation physiology. It stimulated further development of conservation genetics which Otto Frankel had originated first but is now often considered a subdiscipline as well.Description

The rapid decline of established biological systems around the world means that conservation biology is often referred to as a "Discipline with a deadline". Conservation biology is tied closely to ecology in researching the population ecology (dispersal, migration, demographics, effective population size, inbreeding depression, and minimum population viability) of rare or endangered species.Conservation biology is concerned with phenomena that affect the maintenance, loss, and restoration of biodiversity and the science of sustaining evolutionary processes that engender genetic, population, species, and ecosystem diversity. The concern stems from estimates suggesting that up to 50% of all species on the planet will disappear within the next 50 years, which has contributed to poverty, starvation, and will reset the course of evolution on this planet.

Conservation biologists research and educate on the trends and process of biodiversity loss, species extinctions, and the negative effect these are having on our capabilities to sustain the well-being of human society. Conservation biologists work in the field and office, in government, universities, non-profit organizations and industry. The topics of their research are diverse, because this is an interdisciplinary network with professional alliances in the biological as well as social sciences. Those dedicated to the cause and profession advocate for a global response to the current biodiversity crisis based on morals, ethics, and scientific reason. Organizations and citizens are responding to the biodiversity crisis through conservation action plans that direct research, monitoring, and education programs that engage concerns at local through global scales.

History

The conservation of

natural resources is the fundamental problem. Unless we solve that

problem, it will avail us little to solve all others.

– Theodore Roosevelt

Natural resource conservation

Conscious efforts to conserve and protect global biodiversity are a recent phenomenon. Natural resource conservation, however, has a history that extends prior to the age of conservation. Resource ethics grew out of necessity through direct relations with nature. Regulation or communal restraint became necessary to prevent selfish motives from taking more than could be locally sustained, therefore compromising the long-term supply for the rest of the community. This social dilemma with respect to natural resource management is often called the "Tragedy of the Commons".From this principle, conservation biologists can trace communal resource based ethics throughout cultures as a solution to communal resource conflict. For example, the Alaskan Tlingit peoples and the Haida of the Pacific Northwest had resource boundaries, rules, and restrictions among clans with respect to the fishing of sockeye salmon. These rules were guided by clan elders who knew lifelong details of each river and stream they managed.[7][21] There are numerous examples in history where cultures have followed rules, rituals, and organized practice with respect to communal natural resource management.

The Mauryan emperor Ashoka around 250 B.C. issued edicts restricting the slaughter of animals and certain kinds of birds, as well as opened veterinary clinics.

Conservation ethics are also found in early religious and philosophical writings. There are examples in the Tao, Shinto, Hindu, Islamic and Buddhist traditions. In Greek philosophy, Plato lamented about pasture land degradation: "What is left now is, so to say, the skeleton of a body wasted by disease; the rich, soft soil has been carried off and only the bare framework of the district left." In the bible, through Moses, God commanded to let the land rest from cultivation every seventh year. Before the 18th century, however, much of European culture considered it a pagan view to admire nature. Wilderness was denigrated while agricultural development was praised. However, as early as AD 680 a wildlife sanctuary was founded on the Farne Islands by St Cuthbert in response to his religious beliefs.

Early naturalists

White gyrfalcons drawn by John James Audubon

Natural history was a major preoccupation in the 18th century, with grand expeditions and the opening of popular public displays in Europe and North America. By 1900 there were 150 natural history museums in Germany, 250 in Great Britain, 250 in the United States, and 300 in France. Preservationist or conservationist sentiments are a development of the late 18th to early 20th centuries.

Before Charles Darwin set sail on HMS Beagle, most people in the world, including Darwin, believed in special creation and that all species were unchanged. George-Louis Leclerc was one of the first naturalist that questioned this belief. He proposed in his 44 volume natural history book that species evolve due to environmental influences. Erasmus Darwin was also a naturalist who also suggested that species evolved. Erasmus Darwin noted that some species have vestigial structures which are anatomical structures that have no apparent function in the species currently but would have been useful for the species' ancestors. The thinking of these early 18th century naturalist helped to change the mindset and thinking of the early 19th century naturalist.

By the early 19th century biogeography was ignited through the efforts of Alexander von Humboldt, Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin. The 19th-century fascination with natural history engendered a fervor to be the first to collect rare specimens with the goal of doing so before they became extinct by other such collectors. Although the work of many 18th and 19th century naturalists were to inspire nature enthusiasts and conservation organizations, their writings, by modern standards, showed insensitivity towards conservation as they would kill hundreds of specimens for their collections.

Conservation movement

The modern roots of conservation biology can be found in the late 18th-century Enlightenment period particularly in England and Scotland. A number of thinkers, among them notably Lord Monboddo, described the importance of "preserving nature"; much of this early emphasis had its origins in Christian theology.Scientific conservation principles were first practically applied to the forests of British India. The conservation ethic that began to evolve included three core principles: that human activity damaged the environment, that there was a civic duty to maintain the environment for future generations, and that scientific, empirically based methods should be applied to ensure this duty was carried out. Sir James Ranald Martin was prominent in promoting this ideology, publishing many medico-topographical reports that demonstrated the scale of damage wrought through large-scale deforestation and desiccation, and lobbying extensively for the institutionalization of forest conservation activities in British India through the establishment of Forest Departments.

The Madras Board of Revenue started local conservation efforts in 1842, headed by Alexander Gibson, a professional botanist who systematically adopted a forest conservation program based on scientific principles. This was the first case of state conservation management of forests in the world. Governor-General Lord Dalhousie introduced the first permanent and large-scale forest conservation program in the world in 1855, a model that soon spread to other colonies, as well the United States, where Yellowstone National Park was opened in 1872 as the world's first national park.

The term conservation came into widespread use in the late 19th century and referred to the management, mainly for economic reasons, of such natural resources as timber, fish, game, topsoil, pastureland, and minerals. In addition it referred to the preservation of forests (forestry), wildlife (wildlife refuge), parkland, wilderness, and watersheds. This period also saw the passage of the first conservation legislation and the establishment of the first nature conservation societies. The Sea Birds Preservation Act of 1869 was passed in Britain as the first nature protection law in the world[38] after extensive lobbying from the Association for the Protection of Seabirds[39] and the respected ornithologist Alfred Newton.[40] Newton was also instrumental in the passage of the first Game laws from 1872, which protected animals during their breeding season so as to prevent the stock from being brought close to extinction.

One of the first conservation societies was the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, founded in 1889 in Manchester as a protest group campaigning against the use of great crested grebe and kittiwake skins and feathers in fur clothing. Originally known as "the Plumage League", the group gained popularity and eventually amalgamated with the Fur and Feather League in Croydon, and formed the RSPB. The National Trust formed in 1895 with the manifesto to "...promote the permanent preservation, for the benefit of the nation, of lands, ...to preserve (so far practicable) their natural aspect."

In the United States, the Forest Reserve Act of 1891 gave the President power to set aside forest reserves from the land in the public domain. John Muir founded the Sierra Club in 1892, and the New York Zoological Society was set up in 1895. A series of national forests and preserves were established by Theodore Roosevelt from 1901 to 1909. The 1916 National Parks Act, included a 'use without impairment' clause, sought by John Muir, which eventually resulted in the removal of a proposal to build a dam in Dinosaur National Monument in 1959.

In the 20th century, Canadian civil servants, including Charles Gordon Hewitt and James Harkin spearheaded the movement toward wildlife conservation.

Global conservation efforts

In the mid-20th century, efforts arose to target individual species for conservation, notably efforts in big cat conservation in South America led by the New York Zoological Society. In the early 20th century the New York Zoological Society was instrumental in developing concepts of establishing preserves for particular species and conducting the necessary conservation studies to determine the suitability of locations that are most appropriate as conservation priorities; the work of Henry Fairfield Osborn Jr., Carl E. Akeley, Archie Carr and his son Archie Carr III is notable in this era. Akeley for example, having led expeditions to the Virunga Mountains and observed the mountain gorilla in the wild, became convinced that the species and the area were conservation priorities. He was instrumental in persuading Albert I of Belgium to act in defense of the mountain gorilla and establish Albert National Park (since renamed Virunga National Park) in what is now Democratic Republic of Congo.By the 1970s, led primarily by work in the United States under the Endangered Species Act along with the Species at Risk Act (SARA) of Canada, Biodiversity Action Plans developed in Australia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, hundreds of species specific protection plans ensued. Notably the United Nations acted to conserve sites of outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common heritage of mankind. The programme was adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO in 1972. As of 2006, a total of 830 sites are listed: 644 cultural, 162 natural. The first country to pursue aggressive biological conservation through national legislation was the United States, which passed back to back legislation in the Endangered Species Act (1966) and National Environmental Policy Act (1970), which together injected major funding and protection measures to large-scale habitat protection and threatened species research. Other conservation developments, however, have taken hold throughout the world. India, for example, passed the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972.

In 1980, a significant development was the emergence of the urban conservation movement. A local organization was established in Birmingham, UK, a development followed in rapid succession in cities across the UK, then overseas. Although perceived as a grassroots movement, its early development was driven by academic research into urban wildlife. Initially perceived as radical, the movement's view of conservation being inextricably linked with other human activity has now become mainstream in conservation thought. Considerable research effort is now directed at urban conservation biology. The Society for Conservation Biology originated in 1985.

By 1992, most of the countries of the world had become committed to the principles of conservation of biological diversity with the Convention on Biological Diversity; subsequently many countries began programmes of Biodiversity Action Plans to identify and conserve threatened species within their borders, as well as protect associated habitats. The late 1990s saw increasing professionalism in the sector, with the maturing of organisations such as the Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management and the Society for the Environment.

Since 2000, the concept of landscape scale conservation has risen to prominence, with less emphasis being given to single-species or even single-habitat focused actions. Instead an ecosystem approach is advocated by most mainstream conservationists, although concerns have been expressed by those working to protect some high-profile species.

Ecology has clarified the workings of the biosphere; i.e., the complex interrelationships among humans, other species, and the physical environment. The burgeoning human population and associated agriculture, industry, and the ensuing pollution, have demonstrated how easily ecological relationships can be disrupted.

| “ | The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: "What good is it?" If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering. | ” |

| — Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac | ||

Concepts and foundations

Measuring extinction rates

The measure of ongoing species loss is made more complex by the fact that most of the Earth's species have not been described or evaluated. Estimates vary greatly on how many species actually exist (estimated range: 3,600,000-111,700,000) to how many have received a species binomial (estimated range: 1.5-8 million). Less than 1% of all species that have been described beyond simply noting its existence. From these figures, the IUCN reports that 23% of vertebrates, 5% of invertebrates and 70% of plants that have been evaluated are designated as endangered or threatened. Better knowledge is being constructed by The Plant List for actual numbers of species.

Systematic conservation planning

Systematic conservation planning is an effective way to seek and identify efficient and effective types of reserve design to capture or sustain the highest priority biodiversity values and to work with communities in support of local ecosystems. Margules and Pressey identify six interlinked stages in the systematic planning approach:- Compile data on the biodiversity of the planning region

- Identify conservation goals for the planning region

- Review existing conservation areas

- Select additional conservation areas

- Implement conservation actions

- Maintain the required values of conservation areas

Conservation physiology: a mechanistic approach to conservation

Conservation physiology was defined by Steven J. Cooke and colleagues as: 'An integrative scientific discipline applying physiological concepts, tools, and knowledge to characterizing biological diversity and its ecological implications; understanding and predicting how organisms, populations, and ecosystems respond to environmental change and stressors; and solving conservation problems across the broad range of taxa (i.e. including microbes, plants, and animals). Physiology is considered in the broadest possible terms to include functional and mechanistic responses at all scales, and conservation includes the development and refinement of strategies to rebuild populations, restore ecosystems, inform conservation policy, generate decision-support tools, and manage natural resources.' Conservation physiology is particularly relevant to practitioners in that it has the potential to generate cause-and-effect relationships and reveal the factors that contribute to population declines.Conservation biology as a profession

The Society for Conservation Biology is a global community of conservation professionals dedicated to advancing the science and practice of conserving biodiversity. Conservation biology as a discipline reaches beyond biology, into subjects such as philosophy, law, economics, humanities, arts, anthropology, and education. Within biology, conservation genetics and evolution are immense fields unto themselves, but these disciplines are of prime importance to the practice and profession of conservation biology.Is conservation biology an objective science when biologists advocate for an inherent value in nature? Do conservationists introduce bias when they support policies using qualitative description, such as habitat degradation, or healthy ecosystems? As all scientists hold values, so do conservation biologists. Conservation biologists advocate for reasoned and sensible management of natural resources and do so with a disclosed combination of science, reason, logic, and values in their conservation management plans. This sort of advocacy is similar to the medical profession advocating for healthy lifestyle options, both are beneficial to human well-being yet remain scientific in their approach.

There is a movement in conservation biology suggesting a new form of leadership is needed to mobilize conservation biology into a more effective discipline that is able to communicate the full scope of the problem to society at large. The movement proposes an adaptive leadership approach that parallels an adaptive management approach. The concept is based on a new philosophy or leadership theory steering away from historical notions of power, authority, and dominance. Adaptive conservation leadership is reflective and more equitable as it applies to any member of society who can mobilize others toward meaningful change using communication techniques that are inspiring, purposeful, and collegial. Adaptive conservation leadership and mentoring programs are being implemented by conservation biologists through organizations such as the Aldo Leopold Leadership Program.

Approaches

Conservation may be classified as either in-situ conservation, which is protecting an endangered species in its natural habitat, or ex-situ conservation, which occurs outside the natural habitat. In-situ conservation involves protecting or restoring the habitat. Ex-situ conservation, on the other hand, involves protection outside of an organism's natural habitat, such as on reservations or in gene banks, in circumstances where viable populations may not be present in the natural habitat.Also, non-interference may be used, which is termed a preservationist method. Preservationists advocate for giving areas of nature and species a protected existence that halts interference from the humans. In this regard, conservationists differ from preservationists in the social dimension, as conservation biology engages society and seeks equitable solutions for both society and ecosystems. Some preservationists emphasize the potential of biodiversity in a world without humans.

Ethics and values

Conservation biologists are interdisciplinary researchers that practice ethics in the biological and social sciences. Chan states that conservationists must advocate for biodiversity and can do so in a scientifically ethical manner by not promoting simultaneous advocacy against other competing values. A conservationist may be inspired by the resource conservation ethic, which seeks to identify what measures will deliver "the greatest good for the greatest number of people for the longest time." In contrast, some conservation biologists argue that nature has an intrinsic value that is independent of anthropocentric usefulness or utilitarianism. Intrinsic value advocates that a gene, or species, be valued because they have a utility for the ecosystems they sustain. Aldo Leopold was a classical thinker and writer on such conservation ethics whose philosophy, ethics and writings are still valued and revisited by modern conservation biologists.Conservation priorities

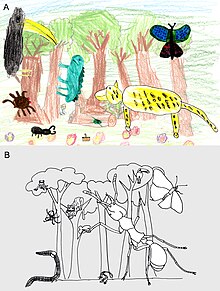

A

pie chart image showing the relative biomass representation in a rain

forest through a summary of children's perceptions from drawings and

artwork (left), through a scientific estimate of actual biomass

(middle), and by a measure of biodiversity (right). Notice that the

biomass of social insects (middle) far outweighs the number of species

(right).

While most in the community of conservation science "stress the importance" of sustaining biodiversity, there is debate on how to prioritize genes, species, or ecosystems, which are all components of biodiversity (e.g. Bowen, 1999). While the predominant approach to date has been to focus efforts on endangered species by conserving biodiversity hotspots, some scientists (e.g) and conservation organizations, such as the Nature Conservancy, argue that it is more cost-effective, logical, and socially relevant to invest in biodiversity coldspots. The costs of discovering, naming, and mapping out the distribution of every species, they argue, is an ill-advised conservation venture. They reason it is better to understand the significance of the ecological roles of species.

Biodiversity hotspots and coldspots are a way of recognizing that the spatial concentration of genes, species, and ecosystems is not uniformly distributed on the Earth's surface. For example, "[...] 44% of all species of vascular plants and 35% of all species in four vertebrate groups are confined to 25 hotspots comprising only 1.4% of the land surface of the Earth."

Those arguing in favor of setting priorities for coldspots point out that there are other measures to consider beyond biodiversity. They point out that emphasizing hotspots downplays the importance of the social and ecological connections to vast areas of the Earth's ecosystems where biomass, not biodiversity, reigns supreme. It is estimated that 36% of the Earth's surface, encompassing 38.9% of the worlds vertebrates, lacks the endemic species to qualify as biodiversity hotspot. Moreover, measures show that maximizing protections for biodiversity does not capture ecosystem services any better than targeting randomly chosen regions. Population level biodiversity (i.e. coldspots) are disappearing at a rate that is ten times that at the species level. The level of importance in addressing biomass versus endemism as a concern for conservation biology is highlighted in literature measuring the level of threat to global ecosystem carbon stocks that do not necessarily reside in areas of endemism. A hotspot priority approach would not invest so heavily in places such as steppes, the Serengeti, the Arctic, or taiga. These areas contribute a great abundance of population (not species) level biodiversity and ecosystem services, including cultural value and planetary nutrient cycling.

Those in favor of the hotspot approach point out that species are irreplaceable components of the global ecosystem, they are concentrated in places that are most threatened, and should therefore receive maximal strategic protections. The IUCN Red List categories, which appear on Wikipedia species articles, is an example of the hotspot conservation approach in action; species that are not rare or endemic are listed the least concern and their Wikipedia articles tend to be ranked low on the importance scale. This is a hotspot approach because the priority is set to target species level concerns over population level or biomass. Species richness and genetic biodiversity contributes to and engenders ecosystem stability, ecosystem processes, evolutionary adaptability, and biomass. Both sides agree, however, that conserving biodiversity is necessary to reduce the extinction rate and identify an inherent value in nature; the debate hinges on how to prioritize limited conservation resources in the most cost-effective way.

Economic values and natural capital

Conservation biologists have started to collaborate with leading global economists to determine how to measure the wealth and services of nature and to make these values apparent in global market transactions. This system of accounting is called natural capital and would, for example, register the value of an ecosystem before it is cleared to make way for development. The WWF publishes its Living Planet Report and provides a global index of biodiversity by monitoring approximately 5,000 populations in 1,686 species of vertebrate (mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians) and report on the trends in much the same way that the stock market is tracked.

This method of measuring the global economic benefit of nature has been endorsed by the G8+5 leaders and the European Commission. Nature sustains many ecosystem services that benefit humanity. Many of the Earth's ecosystem services are public goods without a market and therefore no price or value. When the stock market registers a financial crisis, traders on Wall Street are not in the business of trading stocks for much of the planet's living natural capital stored in ecosystems. There is no natural stock market with investment portfolios into sea horses, amphibians, insects, and other creatures that provide a sustainable supply of ecosystem services that are valuable to society. The ecological footprint of society has exceeded the bio-regenerative capacity limits of the planet's ecosystems by about 30 percent, which is the same percentage of vertebrate populations that have registered decline from 1970 through 2005.

Although a direct market comparison of natural capital is likely insufficient in terms of human value, one measure of ecosystem services suggests the contribution amounts to trillions of dollars yearly. For example, one segment of North American forests has been assigned an annual value of 250 billion dollars; as another example, honey-bee pollination is estimated to provide between 10 and 18 billion dollars of value yearly. The value of ecosystem services on one New Zealand island has been imputed to be as great as the GDP of that region. This planetary wealth is being lost at an incredible rate as the demands of human society is exceeding the bio-regenerative capacity of the Earth. While biodiversity and ecosystems are resilient, the danger of losing them is that humans cannot recreate many ecosystem functions through technological innovation.

Strategic species concepts

Keystone species

Some species, called a keystone species form a central supporting hub unique to their ecosystem. The loss of such a species results in a collapse in ecosystem function, as well as the loss of coexisting species. Keystone species are usually predators due to their ability to control the population of prey in their ecosystem. The importance of a keystone species was shown by the extinction of the Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) through its interaction with sea otters, sea urchins, and kelp. Kelp beds grow and form nurseries in shallow waters to shelter creatures that support the food chain. Sea urchins feed on kelp, while sea otters feed on sea urchins. With the rapid decline of sea otters due to overhunting, sea urchin populations grazed unrestricted on the kelp beds and the ecosystem collapsed. Left unchecked, the urchins destroyed the shallow water kelp communities that supported the Steller's sea cow's diet and hastened their demise. The sea otter was thought to be a keystone species because the coexistence of many ecological associates in the kelp beds relied upon otters for their survival. However this was later questioned by Turvey and Risley, who showed that hunting alone would have driven the Steller's sea cow extinct.Indicator species

An indicator species has a narrow set of ecological requirements, therefore they become useful targets for observing the health of an ecosystem. Some animals, such as amphibians with their semi-permeable skin and linkages to wetlands, have an acute sensitivity to environmental harm and thus may serve as a miner's canary. Indicator species are monitored in an effort to capture environmental degradation through pollution or some other link to proximate human activities. Monitoring an indicator species is a measure to determine if there is a significant environmental impact that can serve to advise or modify practice, such as through different forest silviculture treatments and management scenarios, or to measure the degree of harm that a pesticide may impart on the health of an ecosystem.Government regulators, consultants, or NGOs regularly monitor indicator species, however, there are limitations coupled with many practical considerations that must be followed for the approach to be effective. It is generally recommended that multiple indicators (genes, populations, species, communities, and landscape) be monitored for effective conservation measurement that prevents harm to the complex, and often unpredictable, response from ecosystem dynamics.

Umbrella and flagship species

An example of an umbrella species is the monarch butterfly, because of its lengthy migrations and aesthetic value. The monarch migrates across North America, covering multiple ecosystems and so requires a large area to exist. Any protections afforded to the monarch butterfly will at the same time umbrella many other species and habitats. An umbrella species is often used as flagship species, which are species, such as the giant panda, the blue whale, the tiger, the mountain gorilla and the monarch butterfly, that capture the public's attention and attract support for conservation measures. Paradoxically, however, conservation bias towards flagship species sometimes threatens other species of chief concern.Context and trends

Conservation biologists study trends and process from the paleontological past to the ecological present as they gain an understanding of the context related to species extinction. It is generally accepted that there have been five major global mass extinctions that register in Earth's history. These include: the Ordovician (440 mya), Devonian (370 mya), Permian–Triassic (245 mya), Triassic–Jurassic (200 mya), and Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (66 mya) extinction spasms. Within the last 10,000 years, human influence over the Earth's ecosystems has been so extensive that scientists have difficulty estimating the number of species lost; that is to say the rates of deforestation, reef destruction, wetland draining and other human acts are proceeding much faster than human assessment of species. The latest Living Planet Report by the World Wide Fund for Nature estimates that we have exceeded the bio-regenerative capacity of the planet, requiring 1.6 Earths to support the demands placed on our natural resources.Holocene extinction

An

art scape image showing the relative importance of animals in a rain

forest through a summary of (a) child's perception compared with (b) a

scientific estimate of the importance. The size of the animal represents

its importance. The child's mental image places importance on big cats,

birds, butterflies, and then reptiles versus the actual dominance of

social insects (such as ants).

Conservation biologists are dealing with and have published evidence from all corners of the planet indicating that humanity may be causing the sixth and fastest planetary extinction event. It has been suggested that we are living in an era of unprecedented numbers of species extinctions, also known as the Holocene extinction event. The global extinction rate may be approximately 1,000 times higher than the natural background extinction rate. It is estimated that two-thirds of all mammal genera and one-half of all mammal species weighing at least 44 kilograms (97 lb) have gone extinct in the last 50,000 years. The Global Amphibian Assessment reports that amphibians are declining on a global scale faster than any other vertebrate group, with over 32% of all surviving species being threatened with extinction. The surviving populations are in continual decline in 43% of those that are threatened. Since the mid-1980s the actual rates of extinction have exceeded 211 times rates measured from the fossil record. However, "The current amphibian extinction rate may range from 25,039 to 45,474 times the background extinction rate for amphibians." The global extinction trend occurs in every major vertebrate group that is being monitored. For example, 23% of all mammals and 12% of all birds are Red Listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), meaning they too are threatened with extinction. Even though extinction is natural, the decline in species is happening at such an incredible rate that evolution can simply not match, therefore, leading to the greatest continual mass extinction on Earth. Humans have dominated the planet and our high consumption of resources, along with the pollution generated is affecting the environments in which other species live. There are a wide variety of species that humans are working to protect such as the Hawaiian Crow and the Whooping Crane of Texas. People can also take action on preserving species by advocating and voting for global and national policies that improve climate, under the concepts of climate mitigation and climate restoration.

Status of oceans and reefs

Global assessments of coral reefs of the world continue to report drastic and rapid rates of decline. By 2000, 27% of the world's coral reef ecosystems had effectively collapsed. The largest period of decline occurred in a dramatic "bleaching" event in 1998, where approximately 16% of all the coral reefs in the world disappeared in less than a year. Coral bleaching is caused by a mixture of environmental stresses, including increases in ocean temperatures and acidity, causing both the release of symbiotic algae and death of corals. Decline and extinction risk in coral reef biodiversity has risen dramatically in the past ten years. The loss of coral reefs, which are predicted to go extinct in the next century, threatens the balance of global biodiversity, will have huge economic impacts, and endangers food security for hundreds of millions of people. Conservation biology plays an important role in international agreements covering the world's oceans (and other issues pertaining to biodiversity).The prospects of averting mass extinction seems unlikely when "[...] 90% of all of the large (average approximately ≥50 kg), open ocean tuna, billfishes, and sharks in the ocean" are reportedly gone. Given the scientific review of current trends, the ocean is predicted to have few surviving multi-cellular organisms with only microbes left to dominate marine ecosystems.

Groups other than vertebrates

Serious concerns also being raised about taxonomic groups that do not receive the same degree of social attention or attract funds as the vertebrates. These include fungal (including lichen-forming species), invertebrate (particularly insect) and plant communities where the vast majority of biodiversity is represented. Conservation of fungi and conservation of insects, in particular, are both of pivotal importance for conservation biology. As mycorrhizal symbionts, and as decomposers and recyclers, fungi are essential for sustainability of forests. The value of insects in the biosphere is enormous because they outnumber all other living groups in measure of species richness. The greatest bulk of biomass on land is found in plants, which is sustained by insect relations. This great ecological value of insects is countered by a society that often reacts negatively toward these aesthetically 'unpleasant' creatures.One area of concern in the insect world that has caught the public eye is the mysterious case of missing honey bees (Apis mellifera). Honey bees provide an indispensable ecological services through their acts of pollination supporting a huge variety of agriculture crops. The use of honey and wax have become vastly used throughout the world. The sudden disappearance of bees leaving empty hives or colony collapse disorder (CCD) is not uncommon. However, in 16-month period from 2006 through 2007, 29% of 577 beekeepers across the United States reported CCD losses in up to 76% of their colonies. This sudden demographic loss in bee numbers is placing a strain on the agricultural sector. The cause behind the massive declines is puzzling scientists. Pests, pesticides, and global warming are all being considered as possible causes. (DJS: honey bee populations have rebounded significantly since then.)

Another highlight that links conservation biology to insects, forests, and climate change is the mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) epidemic of British Columbia, Canada, which has infested 470,000 km2 (180,000 sq mi) of forested land since 1999. An action plan has been prepared by the Government of British Columbia to address this problem.

This impact [pine beetle epidemic] converted the forest from a small net carbon sink to a large net carbon source both during and immediately after the outbreak. In the worst year, the impacts resulting from the beetle outbreak in British Columbia were equivalent to 75% of the average annual direct forest fire emissions from all of Canada during 1959–1999.

— Kurz et al.

Conservation biology of parasites

A large proportion of parasite species are threatened by extinction. A few of them are being eradicated as pests of humans or domestic animals, however, most of them are harmless. Threats include the decline or fragmentation of host populations, or the extinction of host species.Threats to biodiversity

Today, many threats to Biodiversity exist. An acronym that can be used to express the top threats of present-day H.I.P.P.O stands for Habitat Loss, Invasive Species, Pollution, Human Population, and Overharvesting. The primary threats to biodiversity are habitat destruction (such as deforestation, agricultural expansion, urban development), and overexploitation (such as wildlife trade). Habitat fragmentation also poses challenges, because the global network of protected areas only covers 11.5% of the Earth's surface. A significant consequence of fragmentation and lack of linked protected areas is the reduction of animal migration on a global scale. Considering that billions of tonnes of biomass are responsible for nutrient cycling across the earth, the reduction of migration is a serious matter for conservation biology.However, human activities need not necessarily cause irreparable harm to the biosphere. With conservation management and planning for biodiversity at all levels, from genes to ecosystems, there are examples where humans mutually coexist in a sustainable way with nature. Even with the current threats to biodiversity there are ways we can improve the current condition and start anew.

Many of the threats to biodiversity, including disease and climate change, are reaching inside borders of protected areas, leaving them 'not-so protected' (e.g. Yellowstone National Park). Climate change, for example, is often cited as a serious threat in this regard, because there is a feedback loop between species extinction and the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Ecosystems store and cycle large amounts of carbon which regulates global conditions. In present day, there have been major climate shifts with temperature changes making survival of some species difficult. The effects of global warming add a catastrophic threat toward a mass extinction of global biological diversity. Conservationists have claimed that not all the species can be saved, and they have to decide which their efforts should be used to protect. This concept is known as the Conservation Triage. The extinction threat is estimated to range from 15 to 37 percent of all species by 2050, or 50 percent of all species over the next 50 years. The current extinction rate is 100-100,000 times more rapid today than the last several billion years.