In number theory, a Gaussian integer is a complex number whose real and imaginary parts are both integers. The Gaussian integers, with ordinary addition and multiplication of complex numbers, form an integral domain, usually written as Z[i]. This integral domain is a particular case of a commutative ring of quadratic integers. It does not have a total ordering that respects arithmetic.

Gaussian integers as lattice points in the complex plane

Basic definitions

The Gaussian integers are the setWhen considered within the complex plane, the Gaussian integers constitute the 2-dimensional integer lattice.

The conjugate of a Gaussian integer a + bi is the Gaussian integer a – bi.

The norm of a Gaussian integer is its product with its conjugate.

The norm is multiplicative, that is, one has

The units of the ring of Gaussian integers (that is the Gaussian integers whose multiplicative inverse is also a Gaussian integer) are precisely the Gaussian integers with norm 1, that is, 1, –1, i and –i.

Euclidean division

Visualization of maximal distance to some Gaussian integer

Gaussian integers have a Euclidean division (division with remainder) similar to that of integers and polynomials. This makes the Gaussian integers a Euclidean domain, and implies that Gaussian integers share with integers and polynomials many important properties such as the existence of a Euclidean algorithm for computing greatest common divisors, Bézout's identity, the principal ideal property, Euclid's lemma, the unique factorization theorem, and the Chinese remainder theorem, all of which can be proved using only Euclidean division.

A Euclidean division algorithm takes, in the ring of Gaussian integers, a dividend a and divisor b ≠ 0, and produces a quotient q and remainder r such that

To prove this, one may consider the complex number quotient x + iy = a/b. There are unique integers m and n such that –1/2 < x – m ≤ 1/2 and –1/2 < y – n ≤ 1/2, and thus N(x – m + i(y – n)) ≤ 1/2. Taking q = m + in, one has

Principal ideals

Since the ring G of Gaussian integers is a Euclidean domain, G is a principal ideal domain, which means that every ideal of G is principal. Explicitly, an ideal I is a subset of a ring R such that every sum of elements of I and every product of an element of I by an element of R belong to I. An ideal is principal, if it consists of all multiples of a single element g, that is, it has the formEvery ideal I in the ring of the Gaussian integers is principal, because, if one chooses in I an nonzero element g of minimal norm, for every element x of I, the remainder of Euclidean division of x by g belongs also to I and has a norm that is smaller than that of g; because of the choice of g, this norm is zero, and thus the remainder is also zero. That is, one has x = qg, where q is the quotient.

For any g, the ideal generated by g is also generated by any associate of g, that is, g, gi, –g, –gi; no other element generates the same ideal. As all the generators of an ideal have the same norm, the norm of an ideal is the norm of any of its generators.

In some circumstances, it is useful to choose, once for all, a generator for each ideal. There are two classical ways for doing that, both considering first the ideals of odd norm. If the g = a + bi has an odd norm a2 + b2, then one of a and b is odd, and the other is even. Thus g has exactly one associate with a real part a that is odd and positive. In its original paper, Gauss did another choice, by choosing the unique associate such that the remainder of its division by 2 + 2i is one. In fact, as N(2 + 2i) = 8, the norm of the remainder is not greater than 4. As this norm is odd, and 3 is not the norm of a Gaussian integer, the norm of the remainder is one, that is, the remainder is a unit. Multiplying g by the inverse of this unit, one finds an associate that has one as a remainder, when divided by 2 + 2i.

If the norm of g is even, then either g = 2kh or g = 2kh(1 + i), where k is a positive integer, and N(h) is odd. Thus, one chooses the associate of g for getting a h which fits the choice of the associates for elements of odd norm.

Gaussian primes

As the Gaussian integers form a principal ideal domain they form also a unique factorization domain. This implies that a Gaussian integer is irreducible (that is, it is not the product of two non-units) if and only if it is prime (that is, it generates a prime ideal).The prime elements of Z[i] are also known as Gaussian primes. An associate of a Gaussian prime is also a Gaussian prime. The conjugate of a Gaussian prime is also a Gaussian prime (this implies that Gaussian primes are symmetric about the real and imaginary axes).

A positive integer is a Gaussian prime if and only if it is a prime number that is congruent to 3 modulo 4 (that is, it may be written 4n + 3, with n a nonnegative integer) (sequence A002145 in the OEIS). The other prime numbers are not Gaussian primes, but each is the product of two conjugate Gaussian primes.

A Gaussian integer a + bi is a Gaussian prime if and only if either:

- one of a, b is zero and absolute value of the other is a prime number of the form 4n + 3 (with n a nonnegative integer), or

- both are nonzero and a2 + b2 is a prime number (which will not be of the form 4n + 3).

It follows that there are three cases for the factorization of a prime number p in the Gaussian integers:

- If p is congruent to 3 modulo 4, then it is a Gaussian prime; in the language of algebraic number theory, p is said to be inert in the Gaussian integers.

- If p is congruent to 1 modulo 4, then it is the product of a Gaussian prime by its conjugate, both of which are non-associated Gaussian primes (neither is the product of the other by a unit); p is said to be a decomposed prime in the Gaussian integers. For example, 5 = (2 + i)(2 − i) and 13 = (3 + 2i)(3 − 2i).

- If p = 2, we have 2 = (1 + i)(1 − i) = i(1 − i)2; that is, 2 is the product of the square of a Gaussian prime by a unit; it is the unique ramified prime in the Gaussian integers.

Unique factorization

As for every unique factorization domain, every Gaussian integer may be factored as a product of a unit and Gaussian primes, and this factorization is unique up to the order of the factors, and the replacement of any prime by any of its associates (together with a corresponding change of the unit factor).If one chooses, once for all, a fixed Gaussian prime for each equivalence class of associated primes, and if one takes only these selected primes in the factorization, then one obtains a prime factorization which is unique up to the order of the factors. With the choices described above, the resulting unique factorization has the form

- either pk = ak + ibk with a odd and positive, and b even,

- or the remainder of the Euclidean division of pk by 2 + 2i equals 1 (this is Gauss's original choice).

Gaussian rationals

The field of Gaussian rationals is the field of fractions of the ring of Gaussian integers. It consists of the complex numbers whose real and imaginary part are both rational.The ring of Gaussian integers is the integral closure of the integers in the Gaussian rationals.

This implies that Gaussian integers are quadratic integers and that a Gaussian rational is a Gaussian integer, if and only if it is a solution of an equation

Greatest common divisor

As for any unique factorization domain, a greatest common divisor (gcd) of two Gaussian integers a, b is a Gaussian integer d that is a common divisor of a and b, which has all common divisors of a and b as divisor. That is (where | denotes the divisibility relation),- d | a and d | b, and

- c | a and c | b implies c | d.

More technically, a greatest common divisor of a and b is a generator of the ideal generated by a and b (this characterization is valid for principal ideal domains, but not, in general, for unique factorization domains).

The greatest common divisor of two Gaussian integers is not unique, but is defined up to the multiplication by a unit. That is, given a greatest common divisor d of a and b, the greatest common divisors of a and b are d, –d, id, and –id.

There are several ways for computing a greatest common divisor of two Gaussian integers a and b. When one know prime factorizations of a and b,

This method of computation works always, but is not as simple as for integers because Euclidean division is more complicate. Therefore, a third method is often preferred for hand-written computations. It consists in remarking that the norm N(d) of the greatest common divisor of a and b is a common divisor of N(a), N(b), and N(a + b). When the greatest common divisor D of these three integers has few factors, then it is easy to test, for common divisor, all Gaussian integers with a norm dividing D.

For example, if a = 5 + 3i, and b = 2 – 8i, one has N(a) = 34, N(b) = 68, and N(a + b) = 74. As the greatest common divisor of the three norms is 2, the greatest common divisor of a and b has 1 or 2 as a norm. As a gaussian integer of norm 2 is necessary associated to 1 + i, and as 1 + i divides a and b, then the greatest common divisor is 1 + i.

If b is replaced by its conjugate b = 2 + 8i, then the greatest common divisor of the three norms is 34, the norm of a, thus one may guess that the greatest common divisor is a, that is, that a | b. In fact, one has 2 + 8i = (5 + 3i)(1 + i).

Congruences and residue classes

Given a Gaussian integer z0, called a modulus, two Gaussian integers z1,z2 are congruent modulo z0, if their difference is a multiple of z0, that is if there exists a Gaussian integer q such that z1 − z2 = qz0. In other words, two Gaussian integers are congruent modulo z0, if their difference belongs to the ideal generated by z0. This is denoted as z1 ≡ z2 (mod z0).The congruence modulo z0 is an equivalence relation (also called a congruence relation), which defines a partition of the Gaussian integers into equivalence classes, called here congruence classes or residue classes. The set of the residue classes is usually denoted Z[i]/z0Z[i], or Z[i]/⟨z0⟩, or simply Z[i]/z0.

The residue class of a Gaussian integer a is the set

Addition and multiplication are compatible with congruences. This means that a1 ≡ b1 (mod z0) and a2 ≡ b2 (mod z0) imply a1 + a2 ≡ b1 + b2 (mod z0) and a1a2 ≡ b1b2 (mod z0). This defines well-defined operations (that is independent of the choice of representatives) on the residue classes:

Examples

- There are exactly two residue classes for the modulus 1 + i, namely 0 = {0, ±2, ±4,…,±1 ± i, ±3 ± i,…} (all multiples of 1 + i), and 1 = {±1, ±3, ±5,…, ±i, ±2 ± i,…}, which form a checkerboard pattern in the complex plane. These two classes form thus a ring with two elements, which is, in fact, a field, the unique (up to an isomorphism) field with two elements, and may thus be identified with the integers modulo 2. These two classes may be considered as a generalization of the partition of integers into even and odd integers. Thus one may speak of even and odd Gaussian integers (Gauss divided further even Gaussian integers into even, that is divisible by 2, and half-even).

- For the modulus 2 there are four residue classes, namely 0, 1, i, 1 + i. These form a ring with four elements, in which x = –x for every x. Thus this ring is not isomorphic with the ring of integers modulo 4, another ring with four elements. One has 1 + i2 = 0, and thus this ring is not the finite field with four elements, nor the direct product of two copies of the ring of integers modulo 2.

- For the modulus 2 + 2i = (i − 1)3 there are eight residue classes, namely 0, ±1, ±i, 1 ± i, 2, whereof four contain only even Gaussian integers and four contain only odd Gaussian integers.

Describing residue classes

All 13 residue classes with their minimal residues (blue dots) in the square Q00 (light green background) for the modulus z0 = 3 + 2i. One residue class with z = 2 − 4i ≡ −i (mod z0) is highlighted with yellow/orange dots.

Given a modulus z0, all elements of a residue class have the same remainder for the Euclidean division by z0, provided one uses the division with unique quotient and remainder, which is described above. Thus enumerating the residue classes is equivalent with enumerating the possible remainders. This can be done geometrically in the following way.

In the complex plane, one may consider a square grid, whose squares are delimited by the two lines

The Gaussian integers in Q00 (or in its boundary) are sometimes called minimal residues because their norm are not greater than the norm of any other Gaussian integer in the same residue class (Gauss called them absolutely smallest residues).

From this one can deduce by geometrical considerations, that the number of residue classes modulo a Gaussian integer z0 = a + bi equals his norm N(z0) = a2 + b2.

Residue class fields

The residue class ring modulo a Gaussian integer z0 is a field if and only if is a Gaussian prime.

is a Gaussian prime.

If z0 is a decomposed prime or the ramified prime 1 + i (that is, if its norm N(z0) is a prime number, which is either 2 or a prime congruent to 1 modulo 4), then the residue class field has a prime number of elements (that is, N(z0)). It is thus isomorphic to the field of the integers modulo N(z0).

If, on the other hand, z0 is an inert prime (that is, N(z0) = p2 is the square of a prime number, which is congruent to 3 modulo 4), then the residue class field has p2 elements, and it is an extension of degree 2 (unique, up to an isomorphism) of the prime field with p elements (the integers modulo p).

Primitive residue class group and Euler's totient function

Many theorems (and their proofs) for moduli of integers can be directly transferred to moduli of Gaussian integers, if one replaces the absolute value of the modulus by the norm. This holds especially for the primitive residue class group (also called multiplicative group of integers modulo n) and Euler's totient function. The primitive residue class group of a modulus z is defined as the subset of its residue classes, which contains all residue classes a that are coprime to z, i.e. (a,z) = 1. Obviously, this system builds a multiplicative group. The number of its elements shall be denoted by ϕ(z) (analogously to Euler's totient function φ(n) for integers n).For Gaussian primes it immediately follows that ϕ(p) = |p|2 − 1 and for arbitrary composite Gaussian integers

- For all a with (a,z) = 1, it holds that aϕ(z) ≡ 1 (mod z).

Historical background

The ring of Gaussian integers was introduced by Carl Friedrich Gauss in his second monograph on quartic reciprocity (1832). The theorem of quadratic reciprocity (which he had first succeeded in proving in 1796) relates the solvability of the congruence x2 ≡ q (mod p) to that of x2 ≡ p (mod q). Similarly, cubic reciprocity relates the solvability of x3 ≡ q (mod p) to that of x3 ≡ p (mod q), and biquadratic (or quartic) reciprocity is a relation between x4 ≡ q (mod p) and x4 ≡ p (mod q). Gauss discovered that the law of biquadratic reciprocity and its supplements were more easily stated and proved as statements about "whole complex numbers" (i.e. the Gaussian integers) than they are as statements about ordinary whole numbers (i.e. the integers).In a footnote he notes that the Eisenstein integers are the natural domain for stating and proving results on cubic reciprocity and indicates that similar extensions of the integers are the appropriate domains for studying higher reciprocity laws.

This paper not only introduced the Gaussian integers and proved they are a unique factorization domain, it also introduced the terms norm, unit, primary, and associate, which are now standard in algebraic number theory.

Unsolved problems

The distribution of the small Gaussian primes in the complex plane

Most of the unsolved problems are related to distribution of Gaussian primes in the plane.

- Gauss's circle problem does not deal with the Gaussian integers per se, but instead asks for the number of lattice points inside a circle of a given radius centered at the origin. This is equivalent to determining the number of Gaussian integers with norm less than a given value.

- The real and imaginary axes have the infinite set of Gaussian primes 3, 7, 11, 19, ... and their associates. Are there any other lines that have infinitely many Gaussian primes on them? In particular, are there infinitely many Gaussian primes of the form 1 + ki?

- Is it possible to walk to infinity using the Gaussian primes as stepping stones and taking steps of a uniformly bounded length? This is known as the Gaussian moat problem; it was posed in 1962 by Basil Gordon and remains unsolved.

![\mathbf {Z} [i]=\{a+bi\mid a,b\in \mathbf {Z} \},\qquad {\text{ where }}i^{2}=-1.](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e1e23ae09a25e0fde987eb1f99eb41e838ce6537)

![{\displaystyle {\bar {a}}:=\left\{z\in \mathbf {Z} [i]\mid z\equiv a{\pmod {z_{0}}}\right\}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fff8f7224fcd09a0b310e70c5211a2283725c677)

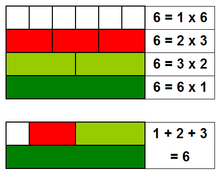

![{\begin{aligned}6&=2^{1}(2^{2}-1)&&=1+2+3,\\[8pt]28&=2^{2}(2^{3}-1)&&=1+2+3+4+5+6+7=1^{3}+3^{3},\\[8pt]496&=2^{4}(2^{5}-1)&&=1+2+3+\cdots +29+30+31\\&&&=1^{3}+3^{3}+5^{3}+7^{3},\\[8pt]8128&=2^{6}(2^{7}-1)&&=1+2+3+\cdots +125+126+127\\&&&=1^{3}+3^{3}+5^{3}+7^{3}+9^{3}+11^{3}+13^{3}+15^{3},\\[8pt]33550336&=2^{12}(2^{13}-1)&&=1+2+3+\cdots +8189+8190+8191\\&&&=1^{3}+3^{3}+5^{3}+\cdots +123^{3}+125^{3}+127^{3}.\end{aligned}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9fa183786d803ce1cab48875dabc4b697ee59225)