From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A

witch-hunt or

witch purge is a search for people labelled "witches" or evidence of

witchcraft, often involving

moral panic or

mass hysteria. The

classical period of witch-hunts in

Early Modern Europe and

Colonial North America took place in the

Early Modern period or about 1450 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the

Reformation and the

Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 35,000 to 100,000 executions.

Including illegal and summary executions it is estimated 200,000 or

more "witches" were tortured, burnt or hanged in the Western world from

1500 until around 1800. The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In other regions, like

Africa and

Asia, contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from

Sub-Saharan Africa and

Papua New Guinea and official legislation against witchcraft is still found in

Saudi Arabia and

Cameroon today.

In current language, "witch hunt" metaphorically means an

investigation usually conducted with much publicity, supposedly to

uncover subversive activity, disloyalty and so on, but really to weaken

political opposition.

Anthropological causes

The wide distribution of the practice of witch-hunts in

geographically and culturally separated societies (Europe, Africa,

India, New Guinea) since the 1960s has triggered interest in the

anthropological background of this behaviour. The belief in

magic and

divination, and attempts to use magic to influence personal well-being (to increase life, win love, etc.) are human

cultural universals.

Belief in witchcraft has been shown to have similarities in

societies throughout the world. It presents a framework to explain the

occurrence of otherwise random misfortunes such as sickness or death,

and the witch sorcerer provides an image of evil. Reports on indigenous practices in the Americas, Asia and Africa collected during the early modern

age of exploration

have been taken to suggest that not just the belief in witchcraft but

also the periodic outbreak of witch-hunts are a human cultural

universal.

One study finds that witchcraft beliefs are associated with

antisocial attitudes: lower levels of trust, charitable giving and group

participation.

Another study finds that income shocks (caused by extreme rainfall)

lead to a large increase in the murder of "witches" in Tanzania.

History

Ancient Near East

Punishment for malevolent

sorcery is addressed in the earliest

law codes which were preserved; in both ancient

Egypt and

Babylonia, where it played a conspicuous part. The

Code of Hammurabi (18th century BC

short chronology) prescribes that

If a man has put a spell upon

another man and it is not yet justified, he upon whom the spell is laid

shall go to the holy river; into the holy river shall he plunge. If the

holy river overcome him and he is drowned, the man who put the spell

upon him shall take possession of his house. If the holy river declares

him innocent and he remains unharmed the man who laid the spell shall be

put to death. He that plunged into the river shall take possession of

the house of him who laid the spell upon him.

Classical antiquity

In Classical Athens, no laws concerning magic survive.

However, cases concerning the harmful effects of

pharmaka

– an ambiguous term that might mean "poison", "medicine", or "magical

drug" – do survive, especially those where the drug caused injury or

death.

Antiphon's speech "

Against the Stepmother for Poisoning" tells of the case of a woman accused of plotting to murder her husband with a

pharmakon;

a slave had previously been executed for the crime, but the son of the

victim claimed that the death had been arranged by his stepmother. The most detailed account of a trial for witchcraft in Classical Greece is the story of

Theoris of Lemnos, who was executed along with her children some time before 338 BC, supposedly for casting incantations and using harmful drugs.

In 451 BC, the

Twelve Tables of

Roman law

had provisions against evil incantations and spells intended to damage

cereal crops. In 331 BC, 170 women were executed as witches in the

context of an

epidemic illness.

Livy emphasizes that this was a scale of persecution without precedent in Rome.

In 186 BC, the Roman senate issued a decree severely restricting

the Bacchanals, ecstatic rites celebrated in honor of Dionysus. Livy

records that this persecution was because "there was nothing wicked,

nothing flagitious, that had not been practiced among them". Consequent to the ban, in 184 BC, about 2,000 people were executed for witchcraft (

veneficium), and in 182–180 BC another 3,000 executions took place,

again triggered by the outbreak of an epidemic. There is no way to

verify the figures reported by Roman historians, but if they are taken

at face value, the scale of the witch-hunts in the

Roman Republic

in relation to the population of Italy at the time far exceeded

anything that took place during the "classical" witch-craze in Early

Modern Europe. Persecution of witches continued in the

Roman Empire until the late 4th century AD and abated only after the introduction of

Christianity as the Roman state religion in the 390s.

The

Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis promulgated by

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

in 81 BC became an important source of late medieval and early modern

European law on witchcraft. This law banned the trading and possession

of harmful drugs and poisons, possession of magical books and other

occult paraphernalia.

Strabo,

Gaius Maecenas and

Cassius Dio all reiterate the traditional Roman opposition against sorcery and divination, and

Tacitus used the term

religio-superstitio to class these outlawed observances. Emperor

Augustus

strengthened legislation aimed at curbing these practices, for instance

in 31 BC, by burning over 2,000 magical books in Rome, except for

certain portions of the hallowed

Sibylline Books. In AD 354, while Tiberius Claudius was emperor, 45 men and 85 women, who were all suspected of sorcery, were executed.

The

Hebrew Bible condemns sorcery.

Deuteronomy

18:10–12 states: "No one shall be found among you who makes a son or

daughter pass through fire, who practices divination, or is a

soothsayer, or an

augur, or a

sorcerer,

or one that casts spells, or who consults ghosts or spirits, or who

seeks oracles from the dead. For whoever does these things is abhorrent

to the Lord"; and

Exodus 22:18 prescribes: "thou shalt not suffer a witch to live". Tales like that of

1 Samuel 28, reporting how

Saul "hath cut off those that have familiar spirits, and the wizards, out of the land", suggest that in practice sorcery could at least lead to exile.

In the Judaean

Second Temple period, Rabbi

Simeon ben Shetach

in the 1st century BC is reported to have sentenced to death eighty

women who had been charged with witchcraft on a single day in

Ashkelon.

Later the women's relatives took revenge by bringing (reportedly) false

witnesses against Simeon's son and causing him to be executed in turn.

Late antiquity

The 6th-century AD

Getica of

Jordanes records a persecution and expulsion of witches among the

Goths in a mythical account of the origin of the

Huns. The ancient fabled King

Filimer is said to have

found among his people certain witches, whom he called in his native tongue Haliurunnae.

Suspecting these women, he expelled them from the midst of his race and

compelled them to wander in solitary exile afar from his army. There

the unclean spirits, who beheld them as they wandered through the

wilderness, bestowed their embraces upon them and begat this savage

race, which dwelt at first in the swamps, a stunted, foul and puny

tribe, scarcely human, and having no language save one which bore but

slight resemblance to human speech.

Middle Ages

Christianisation in the Early Middle Ages

The Councils of

Elvira (306),

Ancyra (314), and

Trullo

(692) imposed certain ecclesiastical penances for devil-worship. This

mild approach represented the view of the Church for many centuries. The

general desire of the

Catholic Church's clergy to check fanaticism about witchcraft and

necromancy is shown in the decrees of the

Council of Paderborn,

which, in 785, explicitly outlawed condemning people as witches and

condemned to death anyone who burnt a witch. The Lombard code of 643

states:

Let nobody presume to kill a foreign serving maid or

female servant as a witch, for it is not possible, nor ought to be

believed by Christian minds.

This conforms to the teachings of the

Canon Episcopi of circa 900 AD (alleged to date from 314 AD), which, following the thoughts of

Augustine of Hippo,

stated that witchcraft did not exist and that to teach that it was a

reality was, itself, false and heterodox teaching. Other examples

include an Irish synod in 800,

[25] and a sermon by

Agobard of Lyons (810).

King Kálmán (Coloman) of Hungary, in Decree 57 of his First Legislative Book (published in 1100), banned witch hunting because he said, "witches do not exist". The "Decretum" of

Burchard, Bishop of Worms

(about 1020), and especially its 19th book, often known separately as

the "Corrector", is another work of great importance. Burchard was

writing against the superstitious belief in magical potions, for

instance, that may produce impotence or abortion. These were also

condemned by several Church Fathers.

But he altogether rejected the possibility of many of the alleged

powers with which witches were popularly credited. Such, for example,

were nocturnal riding through the air, the changing of a person's

disposition from love to hate, the control of thunder, rain, and

sunshine, the transformation of a man into an animal, the intercourse of

incubi and

succubi

with human beings and other such superstitions. Not only the attempt to

practice such things, but the very belief in their possibility, is

treated by Burchard as false and superstitious.

Pope Gregory VII, in 1080, wrote to King

Harald III of Denmark

forbidding witches to be put to death upon presumption of their having

caused storms or failure of crops or pestilence. Neither were these the

only examples of an effort to prevent unjust suspicion to which such

poor creatures might be exposed.

On many different occasions, ecclesiastics who spoke with authority did

their best to disabuse the people of their superstitious belief in

witchcraft. This, for instance, is the general purport of the book,

Contra insulsam vulgi opinionem de grandine et tonitruis ("Against the foolish belief of the common sort concerning hail and thunder"), written by

Agobard (d. 841),

Archbishop of Lyons. A comparable situation in

Russia is suggested in a sermon by

Serapion of Vladimir (written in 1274/5), where the popular superstition of witches causing crop failures is denounced.

Early secular laws against witchcraft include those promulgated by King

Athelstan (924–939):

And we have ordained respecting witch-crafts, and lybacs [read lyblac "sorcery"], and morthdaeds ["murder, mortal sin"]:

if any one should be thereby killed, and he could not deny it, that he

be liable in his life. But if he will deny it, and at threefold ordeal

shall be guilty; that he be 120 days in prison: and after that let

kindred take him out, and give to the king 120 shillings, and pay the wer to his kindred, and enter into borh for him, that he evermore desist from the like.

In some prosecutions for witchcraft, torture (permitted by the

Roman civil law) apparently took place. However,

Pope Nicholas I (866), prohibited the use of torture altogether, and a similar decree may be found in the

Pseudo-Isidorian Decretals.

Later Middle Ages

The manuals of the Roman Catholic

Inquisition

remained highly skeptical of witch accusations, although there was

sometimes an overlap between accusations of heresy and of witchcraft,

particularly when, in the 13th century, the newly formed Inquisition was

commissioned to deal with the

Cathars

of Southern France, whose teachings were charged with containing an

admixture of witchcraft and magic. Although it has been proposed that

the witch-hunt developed in Europe from the early 14th century, after

the Cathars and the

Templar Knights were suppressed, this hypothesis has been rejected independently by two historians (Cohn 1975; Kieckhefer 1976).

In 1258,

Pope Alexander IV declared a canon that alleged witchcraft was not to be investigated by the Church. Although

Pope John XXII had later authorized the Inquisition to prosecute sorcerers in 1320, inquisitorial courts rarely dealt with witchcraft save incidentally when investigating heterodoxy.

In the case of the

Madonna Oriente, the Inquisition of

Milan was not sure what to do with two women who in 1384 confessed to have participated the society around Signora Oriente or

Diana. Through their confessions, both of them conveyed the traditional folk

beliefs of white magic. The women were accused again in 1390, and

condemned by the inquisitor. They were eventually executed by the

secular arm.

In a notorious case in 1425,

Hermann II, Count of Celje accused his daughter-in-law

Veronika of Desenice

of witchcraft – and, though she was acquitted by the court, he had her

drowned. The accusations of witchcraft are, in this case, considered to

have been a pretext for Hermann to get rid of an "unsuitable match,"

Veronika being born into the lower nobility and thus "unworthy" of his

son.

A Catholic figure who preached against witchcraft was popular Franciscan preacher

Bernardino of Siena

(1380–1444). Bernardino's sermons reveal both a phenomenon of

superstitious practices and an over-reaction against them by the common

people.

However, it is clear that Bernardino had in mind not merely the use of

spells and enchantments and such like fooleries but much more serious

crimes, chiefly murder and infanticide. This is clear from his

much-quoted sermon of 1427, in which he says:

One of them told and confessed, without any pressure,

that she had killed thirty children by bleeding them ... [and] she

confessed more, saying she had killed her own son ... Answer me: does it

really seem to you that someone who has killed twenty or thirty little

children in such a way has done so well that when finally they are

accused before the Signoria you should go to their aid and beg mercy for

them?

Transition to the early modern witch-hunts

The

Malleus Maleficarum

(the 'Hammer against the Witches'), published in 1487, accused women of

destroying men by planting bitter herbs throughout the field.

The resurgence of witch-hunts at the end of the medieval period,

taking place with at least partial support or at least tolerance on the

part of the Church, was accompanied with a number of developments in

Christian doctrine, for example the recognition of the existence of

witchcraft as a form of Satanic influence and its classification as a

heresy. As

Renaissance occultism gained traction among the educated classes, the belief in witchcraft, which in the medieval period had been part of the

folk religion

of the uneducated rural population at best, was incorporated into an

increasingly comprehensive theology of Satan as the ultimate source of

all

maleficium. These doctrinal shifts were completed in the mid-15th century, specifically in the wake of the

Council of Basel and centered on the

Duchy of Savoy in the western Alps, leading to an early series of witch trials by both secular and ecclesiastical courts in the second half of the 15th century.

In 1484,

Pope Innocent VIII issued

Summis desiderantes affectibus, a

Papal bull

authorizing the "correcting, imprisoning, punishing and chastising" of

devil-worshippers who have "slain infants", among other crimes. He did

so at the request of inquisitor

Heinrich Kramer, who had been refused permission by the local bishops in Germany to investigate. However, historians such as

Ludwig von Pastor insist that the bull neither allowed anything new nor was necessarily binding on Catholic consciences. Three years later in 1487, Kramer published the notorious

Malleus Maleficarum

(lit., 'Hammer against the Evildoers') which, because of the newly

invented printing presses, enjoyed a wide readership. The book was soon

banned by the Church in 1490, and Kramer was

censured, but it was nevertheless reprinted in 14 editions by 1520 and became unduly influential in the secular courts. In 1538, the

Spanish Inquisition cautioned its members not to believe what the

Malleus said, even when it presented apparently firm evidence.

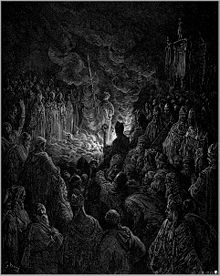

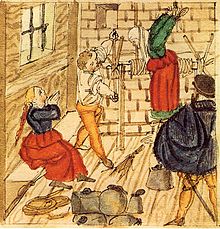

Early Modern Europe

The torture used against accused witches, 1577

The witch trials in

Early Modern Europe

came in waves and then subsided. There were trials in the 15th and

early 16th centuries, but then the witch scare went into decline, before

becoming a major issue again and peaking in the 17th century;

particularly during the

Thirty Years War.

What had previously been a belief that some people possessed

supernatural abilities (which were sometimes used to protect the people)

now became a sign of a pact between the people with supernatural

abilities and the devil. To justify the killings, Protestant

Christianity and its proxy secular institutions deemed witchcraft as

being associated to wild

Satanic ritual parties in which there was much naked dancing and

cannibalistic infanticide. It was also seen as

heresy for going against the first of the

ten commandments ("You shall have no other gods before me") or as

violating majesty, in this case referring to the divine majesty, not the worldly.

Further scripture was also frequently cited, especially the Exodus

decree that "thou shalt not suffer a witch to live" (Exodus 22:18),

which many supported.

Witch-hunts were seen across early modern Europe, but the most

significant area of witch-hunting in modern Europe is often considered

to be central and southern Germany.

Germany was a late starter in terms of the numbers of trials, compared

to other regions of Europe. Witch-hunts first appeared in large numbers

in southern France and Switzerland during the 14th and 15th centuries.

The peak years of witch-hunts in southwest Germany were from 1561 to

1670. The

first major persecution

in Europe, when witches were caught, tried, convicted, and burned in

the imperial lordship of Wiesensteig in southwestern Germany, is

recorded in 1563 in a pamphlet called "True and Horrifying Deeds of 63

Witches".

Witchcraft persecution spread to all areas of Europe, including

Scotland and the northernmost periphery of Europe in northern Norway.

Learned European ideas about witchcraft, demonological ideas, strongly

influenced the hunt of witches in the North.

In Denmark, the burning of witches increased following the

reformation of 1536.

Christian IV of Denmark, in particular, encouraged this practice, and hundreds of people were convicted of

witchcraft and burnt. In the district of Finnmark, northern Norway, severe witchcraft trials took place during the period 1600–1692. A memorial of international format,

Steilneset Memorial, has been built to commemorate the victims of the Finnmark witchcraft trials. In England, the

Witchcraft Act of 1542 regulated the penalties for witchcraft. In the

North Berwick witch trials in Scotland, over 70 people were accused of witchcraft on account of bad weather when

James VI of Scotland, who shared the Danish king's interest in witch trials, sailed to Denmark in 1590 to meet his betrothed

Anne of Denmark. The

Pendle witch trials of 1612 are among the most famous witch trials in English history.

The

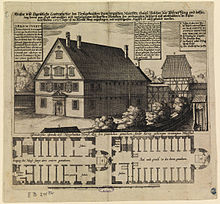

Malefizhaus of

Bamberg, Germany, where suspected witches were held and interrogated. 1627 engraving.

In England, witch-hunting would reach its apex in 1644 to 1647 due to the work of

Matthew Hopkins.

Although operating without an official Parliament commission, Hopkins

(calling himself Witchfinder General) and his accomplices charged hefty

fees to towns during the

English Civil War. Hopkins' witch hunting spree was brief but significant: 300 convictions and deaths are attributed to his work.

Hopkins wrote a book on his methods, describing his fortuitous

beginnings as a witch hunter, the methods used to extract confessions,

and the tests he employed to test the accused: stripping them naked to

find the

Witches' mark,

the "swimming" test, and

pricking the skin.

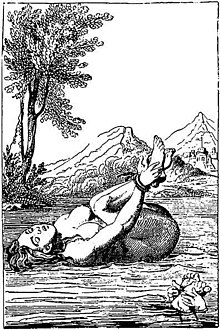

The swimming test, which included throwing a witch into water strapped

to a chair to see if she floated, was discontinued in 1645 due to a

legal challenge. The 1647 book,

The Discovery of Witches, was soon influential in legal texts. The book was used in the

American colonies as early as May 1647, when

Margaret Jones was executed for witchcraft in

Connecticut, the first of 17 people executed for witchcraft in the Colonies from 1647 to 1663.

Witch-hunts in North America began about the time of Hopkins. In 1645, forty-six years before the notorious

Salem witch trials,

Springfield, Massachusetts experienced America's first accusations of

witchcraft

when husband and wife Hugh and Mary Parsons accused each other of

witchcraft. In America's first witch trial, Hugh was found innocent,

while Mary was acquitted of witchcraft but she was still sentenced to be

hanged as punishment for the death of her child. She died in prison. About eighty people throughout England's

Massachusetts Bay Colony were accused of practicing witchcraft; thirteen women and two men were executed in a witch-hunt that occurred throughout

New England and lasted from 1645–1663. The

Salem witch trials followed in 1692–93.

Once a case was brought to trial, the prosecutors hunted for

accomplices. Magic was not considered to be wrong because it failed, but

because it worked effectively for the wrong reasons. Witchcraft was a

normal part of everyday life. Witches were often called for, along with

religious ministers, to help the ill or to deliver a baby. They held

positions of spiritual power in their communities. When something went

wrong, no one questioned the ministers or the power of the witchcraft.

Instead, they questioned whether the witch intended to inflict harm or

not.

Current scholarly estimates of the number of people executed for witchcraft vary between about 40,000 and 100,000. The total number of witch trials in Europe which are known to have ended in executions is around 12,000. Prominent contemporaneous critics of witch hunts included Gianfrancesco Ponzinibio (fl. 1520),

Johannes Wier (1515–1588),

Reginald Scot (1538–1599),

Cornelius Loos (1546–1595),

Anton Praetorius (1560–1613),

Alonso Salazar y Frías (1564–1636),

Friedrich Spee (1591–1635), and

Balthasar Bekker (1634–1698)..Among the largest and most notable of these trials were the

Trier witch trials (1581–1593), the

Fulda witch trials (1603–1606), the

Würzburg witch trial (1626–1631) and the

Bamberg witch trials (1626–1631).

Execution statistics

An image of suspected witches being hanged in England, published in 1655

Modern scholarly estimates place the total number of executions for

witchcraft in the 300-year period of European witch-hunts in the five

digits, mostly at roughly between 40,000 and 50,000 (see table below for

details), but some estimate there were 200,000 to 500,000 executed for witchcraft, and others estimated 1,000,000 or more.

The majority of those accused were from the lower economic classes in

European society, although in rarer cases high-ranking individuals were

accused as well. On the basis of this evidence, Scarre and Callow

asserted that the "typical witch was the wife or widow of an

agricultural labourer or small tenant farmer, and she was well known for

a quarrelsome and aggressive nature."

While it appears to be the case that the clear majority of

victims in Germany were women, in other parts of Europe the witch-hunts

targeted primarily men, thus in Iceland 92% of the accused were men, in

Estonia 60%, and in Moscow two-thirds of those accused were male.

At one point during the Würzburg trials of 1629, children made up

60% of those accused, although this had declined to 17% by the end of

the year. The claim that "millions of witches" (often: "

nine million witches") were killed in Europe occasionally found in popular literature is spurious, and ultimately due to a 1791 pamphlet by

Gottfried Christian Voigt.

Approximate statistics on the number of trials for witchcraft

and executions in various regions of Europe in the period 1450–1750:

| Region |

Number of trials |

Number of executions

|

| British Isles and North America |

~5,000 |

~1,500–2,000

|

| Holy Roman Empire (Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, Lorraine, Austria including Czech lands – Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia) |

~50,000 |

~25,000–30,000

|

| France |

~3,000 |

~1,000

|

| Scandinavia |

~5,000 |

~1,700–2,000

|

| Central & Eastern Europe (Poland-Lithuania, Hungary and Russia) |

~7,000 |

~2,000

|

| Southern Europe (Spain, Portugal and Italy) |

~10,000 |

~1,000

|

| Total: |

~80,000 |

~35,000

|

End of European witch hunts in the 18th century

The drowning of an alleged witch, with

Thomas Colley as the incitor

In England and Scotland between 1542 and 1735, a series of

Witchcraft Acts enshrined into law the punishment (often with death, sometimes with

incarceration) of individuals practising or claiming to practice witchcraft and magic.

The last executions for witchcraft in England had taken place in 1682,

when Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles, and Susanna Edwards were executed

at Exeter. In 1711,

Joseph Addison published an article in the highly respected

The Spectator

journal (No. 117) criticizing the irrationality and social injustice in

treating elderly and feeble women (dubbed "Moll White") as witches.

Jane Wenham was among the last subjects of a typical witch trial in England in 1712, but was pardoned after her conviction and set free.

Kate Nevin was hunted for three weeks and eventually suffered death by

Faggot and Fire at Monzie in

Perthshire, Scotland in 1715.

Janet Horne

was executed for witchcraft in Scotland in 1727. The final Act of 1735

led to prosecution for fraud rather than witchcraft since it was no

longer believed that the individuals had actual supernatural powers or

traffic with

Satan. The 1735 Act continued to be used until the 1940s to prosecute individuals such as

spiritualists and

gypsies. The act was finally repealed in 1951.

The last execution of a witch in the Dutch Republic was probably in 1613. In Denmark, this took place in 1693 with the execution of

Anna Palles. In other parts of Europe, the practice died down later. In France the last person to be executed for witchcraft was

Louis Debaraz in 1745. In Germany the last death sentence was that of

Anna Schwegelin in

Kempten in 1775 (although not carried out). The last known official witch-trial was the

Doruchów witch trial in Poland in 1783. Two unnamed women were executed in

Poznań, Poland, in 1793, in proceedings of dubious legitimacy.

Anna Göldi was executed in

Glarus, Switzerland in 1782 and

Barbara Zdunk

in Prussia in 1811. Both women have been identified as the last women

executed for witchcraft in Europe, but in both cases, the official

verdict did not mention witchcraft, as this had ceased to be recognized

as a criminal offense.

India

There is no documented evidence of witch hunting in India before 1792.

The earliest evidence of witch-hunts in India can be found in the

Santhal witch trials in 1792. In the

Singhbhum district of the

Chhotanagpur division in

British India,

not only were those accused of being witches murdered, but also those

related to the accused to ensure that they won't avenge the deaths (Roy

Choudhary 1958: 88). The Chhotanagpur region was majorly populated by an

adivasi

population called the Santhals. The existence of witches was a belief

central to the Santhals. Witches were feared and were supposed to be

engaged in anti-social activities. They were also supposed to have the

power to kill people by feeding on their entrails, and causing fevers in

cattle among other evils. Therefore, according to the adivasi

population the cure to their disease and sickness was the elimination of

these witches who were seen as the cause.

The practice of witch hunt among Santhals was more brutal than

that in Europe. Unlike Europe where witches were strangulated before

being burnt, the santhals forced them "..to eat human excreta and drink

blood before throwing them into the flames."

The British banned the persecution of witches in Gujarat,

Rajasthan and Chhotanagpur in the 1840s–1850s. They saw the practise as

barbaric and tried to dismantle the belief in witchcraft by providing

medical facilities. However, they undermined the extent to which the

belief was socially embedded. Despite the ban, very few cases were

reported as witch-hunting was not seen as a crime. The Santhals believed

that the ban in fact allowed the witches to flourish. Thus, the effect

of the ban was contrary to what the British had intended. During

1857–58, there was a surge in witch hunting. This can be viewed as a

mode of resistance to the British rule as part of the larger revolt of

1857.

Modern cases

Monument for the victims of the witch-hunts of 16th- and 17th-century Bernau, Germany by

Annelie Grund

Witch hunts still occur today in societies where belief in

magic is prevalent. In most cases, these are instances of

lynching and burnings, reported with some regularity from much of

Sub-Saharan Africa, from rural

North India

and from Papua New Guinea. In addition, there are some countries that

have legislation against the practice of sorcery. The only country where

witchcraft remains legally punishable by

death is Saudi Arabia.

Witch hunts in modern times are continuously reported by the

UNHCR of the

UNO

as a massive violation of human rights. Most of the accused are women

and children but can also be elderly people or marginalised groups of

the community such as

albinos and the

HIV-infected.

These victims are often considered burdens to the community, and as a

result are often driven out, starved to death, or killed violently,

sometimes by their own families in acts of

social cleansing.

The causes of witch hunts include poverty, epidemics, social crises and

lack of education. The leader of the witch hunt, often a prominent

figure in the community or a "witch doctor", may also gain economic

benefit by charging for an

exorcism or by selling body parts of the murdered.

Sub-Saharan Africa

In many societies of

Sub-Saharan Africa,

the fear of witches drives periodic witch-hunts during which specialist

witch-finders identify suspects, with death by mob often the result. Countries particularly affected by this phenomenon include

South Africa,

Cameroon, the

Democratic Republic of the Congo, the

Gambia,

Ghana,

Kenya,

Sierra Leone,

Tanzania, and

Zambia.

Witch-hunts against children were reported by the BBC in 1999 in the Congo and in Tanzania, where the government responded to attacks on women accused of being witches for having red eyes.

[91] A lawsuit was launched in 2001 in Ghana, where witch-hunts are also common, by a woman accused of being a witch. Witch-hunts in Africa are often led by relatives seeking the property of the accused victim.

Audrey I. Richards, in the journal

Africa, relates in 1935 an instance when a new wave of witchfinders, the

Bamucapi, appeared in the villages of the

Bemba people of Zambia.

They dressed in European clothing, and would summon the headman to

prepare a ritual meal for the village. When the villagers arrived they

would view them all in a

mirror,

and claimed they could identify witches with this method. These witches

would then have to "yield up his horns"; i.e. give over the

horn containers for

curses and evil

potions to the witch-finders. The bamucapi then made all drink a potion called

kucapa which would cause a witch to die and swell up if he ever tried such things again.

The villagers related that the witch-finders were always right

because the witches they found were always the people whom the village

had feared all along. The bamucapi utilised a mixture of Christian and

native religious traditions to account for their powers and said that

God (not specifying which God) helped them to prepare their medicine. In

addition, all witches who did not attend the meal to be identified

would be called to account later on by their master, who had risen from

the dead, and who would force the witches by means of drums to go to the

graveyard, where they would die. Richards noted that the bamucapi

created the sense of danger in the villages by rounding up

all

the horns in the village, whether they were used for anti-witchcraft

charms, potions, snuff or were indeed receptacles of black magic.

The Bemba people believed misfortunes such as

wartings,

hauntings and

famines

to be just actions sanctioned by the High-God Lesa. The only agency

which caused unjust harm was a witch, who had enormous powers and was

hard to detect. After white rule of Africa, beliefs in sorcery and

witchcraft grew, possibly because of the social strain caused by new

ideas, customs and laws, and also because the courts no longer allowed

witches to be tried.

Amongst the

Bantu tribes of Southern Africa, the

witch smellers

were responsible for detecting witches. In parts of Southern Africa,

several hundred people have been killed in witch hunts since 1990.

Cameroon has re-established witchcraft-accusations in courts after its independence in 1967.

It was reported on 21 May 2008 that in Kenya a mob had

burnt to death at least 11 people accused of witchcraft.

In March 2009, Amnesty International reported that up to 1,000

people in the Gambia had been abducted by government-sponsored "witch

doctors" on charges of witchcraft, and taken to detention centers where

they were forced to drink poisonous concoctions. On 21 May 2009,

The New York Times reported that the alleged witch-hunting campaign had been sparked by the Gambian President,

Yahya Jammeh.

In Sierra Leone, the witch-hunt is an occasion for a sermon by the

kɛmamɔi (native

Mende

witch-finder) on social ethics : "Witchcraft ... takes hold in people's

lives when people are less than fully open-hearted. All wickedness is

ultimately because people hate each other or are jealous or suspicious

or afraid. These emotions and motivations cause people to act

antisocially". The response by the populace to the

kɛmamɔi is that "they valued his work and would learn the lessons he came to teach them, about social responsibility and cooperation."

South-Central Asia

In

India,

labeling a woman as a witch is a common ploy to grab land, settle

scores or even to punish her for turning down sexual advances. In a

majority of the cases, it is difficult for the accused woman to reach

out for help and she is forced to either abandon her home and family or

driven to commit suicide. Most cases are not documented because it is

difficult for poor and illiterate women to travel from isolated regions

to file police reports. Less than 2% of those accused of witch-hunting

are actually convicted, according to a study by the Free Legal Aid

Committee, a group that works with victims in the state of Jharkhand.

A 2010 estimate places the number of women killed as witches in

India at between 150 and 200 per year, or a total of 2,500 in the period

of 1995 to 2009. The lynchings are particularly common in the poor

northern states of

Jharkhand,

Bihar and the central state of

Chhattisgarh.

Witch hunts are also taking place among the tea garden workers in Jalpaiguri, West Bengal India.

The witch hunts in Jalpaiguri are less known, but are motivated by the

stress in the tea industry on the lives of the adivasi workers.

Witch hunts in

Nepal are common, and are targeted especially against low-caste women. The main causes of witchcraft related violence include widespread

belief in superstition, lack of education, lack of public awareness,

illiteracy, caste system, male domination, and economic dependency of

women on men. The victims of this form of violence are often beaten,

tortured, publicly humiliated, and murdered. Sometimes, the family

members of the accused are also assaulted.

In 2010, Sarwa Dev Prasad Ojha, minister for women and social welfare,

said, "Superstitions are deeply rooted in our society, and the belief in

witchcraft is one of the worst forms of this."

Papua New Guinea

Though the practice of "white" magic (such as

faith healing) is legal in Papua New Guinea, the 1976 Sorcery Act imposed a penalty of up to 2 years in prison for the practice of

"black" magic,

until the Act was repealed in 2013. In 2009, the government reports

that extrajudicial torture and murder of alleged witches – usually lone

women – are spreading from the highland areas to cities as villagers

migrate to urban areas.

For example, in June 2013, four women were accused of witchcraft

because the family "had a 'permanent house' made of wood, and the family

had tertiary educations and high social standing". All of the women were tortured and Helen Rumbali was beheaded.

Helen Hakena, chairwoman of the North Bougainville Human Rights

Committee, said that the accusations started because of economic

jealousy born of a mining boom.

Reports by U.N. agencies, Amnesty International, Oxfam and

anthropologists show that "attacks on accused sorcerers and witches –

sometimes men, but most commonly women – are frequent, ferocious and

often fatal."

It's estimated about 150 cases of violence and killings are occurring

each year in just the province of Simbu in Papua New Guinea alone.

Reports indicate this practice of witch hunting has in some places

evolved into "something more malignant, sadistic and voyeuristic."

One woman who was attacked by young men from a nearby village "had her

genitals burned and fused beyond functional repair by the repeated

intrusions of red-hot irons."

Few incidents are ever reported, according to the 2012 Law Reform

Commission which concluded that they have increased since the 1980s.

Saudi Arabia

Witchcraft or sorcery remains a criminal offense in

Saudi Arabia, although the precise nature of the crime is undefined.

The frequency of prosecutions for this in the country as whole is

unknown. However, in November 2009, it was reported that 118 persons

had been arrested in the province of Makkah that year for practicing

magic and "using the Book of Allah in a derogatory manner", 74% of them

being female. According to

Human Rights Watch

in 2009, prosecutions for witchcraft and sorcery are proliferating and

"Saudi courts are sanctioning a literal witch hunt by the religious

police."

In 2006, an illiterate Saudi woman,

Fawza Falih,

was convicted of practising witchcraft, including casting an impotence

spell, and sentenced to death by beheading, after allegedly being beaten

and forced to fingerprint a false confession that had not been read to

her.

After an appeal court had cast doubt on the validity of the death

sentence because the confession had been retracted, the lower court

reaffirmed the same sentence on a different basis.

In 2007, Mustafa Ibrahim, an Egyptian national, was executed,

having been convicted of using sorcery in an attempt to separate a

married couple, as well as of adultery and of desecrating the Quran.

Also in 2007, Abdul Hamid Bin Hussain Bin Moustafa al-Fakki, a

Sudanese national, was sentenced to death after being convicted of

producing a spell that would lead to the reconciliation of a divorced

couple.

In 2009,

Ali Sibat,

a Lebanese television presenter who had been arrested whilst on a

pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia, was sentenced to death for witchcraft

arising out of his fortune-telling on an Arab satellite channel.

His appeal was accepted by one court, but a second in Medina upheld his

death sentence again in March 2010, stating that he deserved it as he

had publicly practised sorcery in front of millions of viewers for

several years.

In November 2010, the Supreme Court refused to ratify the death

sentence, stating that there was insufficient evidence that his actions

had harmed others.

On 12 December 2011, Amina bint Abdulhalim Nassar was beheaded in

Al Jawf Province after being convicted of practicing witchcraft and sorcery. Another very similar situation occurred to Muree bin Ali bin Issa al-Asiri and he was beheaded on 19 June 2012 in the

Najran Province.

ISIS (Islamic State)

On 29 and 30 June 2015, militants of the

radical Islam terrorist group

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or ISIS) beheaded two couples on accusations of sorcery and using "magic for medicine" in

Deir ez-Zor province of the self-proclaimed Islamic State. Earlier on, the ISIL militants beheaded several "magicians" and street illusionists in Syria, Iraq and Libya.

Figurative use of the term

Western media frequently write of a '

Stalinist witch-hunt' or a '

McCarthyite witch-hunt, In these cases, the word 'witch-hunt' is used as a

metaphor to illustrate the brutal and ruthless way in which political opponents are denigrated and persecuted.