Moral relativism may be any of several philosophical positions concerned with the differences in moral judgments across different people and cultures. Descriptive moral relativism holds only that some people do in fact disagree about what is moral; meta-ethical moral relativism holds that in such disagreements, nobody is objectively right or wrong; and normative moral relativism holds that because nobody is right or wrong, we ought to tolerate the behavior of others even when we disagree about the morality of it.

Not all descriptive relativists adopt meta-ethical relativism, and moreover, not all meta-ethical relativists adopt normative relativism. Richard Rorty, for example, argued that relativist philosophers believe "that the grounds for choosing between such opinions is less algorithmic than had been thought", but not that any belief is as valid as any other.

Moral relativism has been debated for thousands of years, from ancient Greece and India to the present day, in diverse fields including art, philosophy, science, and religion.

Variations

Descriptive

Descriptive moral relativism is merely the positive or descriptive position that there exist, in fact, fundamental disagreements about the right course of action even when the same facts hold true and the same consequences seem likely to arise. It is the observation that different cultures have different moral standards.Descriptive relativists do not necessarily advocate the tolerance of all behavior in light of such disagreement; that is to say, they are not necessarily normative relativists. Likewise, they do not necessarily make any commitments to the semantics, ontology, or epistemology of moral judgement; that is, not all descriptive relativists are meta-ethical relativists.

Descriptive relativism is a widespread position in academic fields such as anthropology and sociology, which simply admit that it is incorrect to assume that the same moral or ethical frameworks are always in play in all historical and cultural circumstances.

Meta-ethical

Meta-ethical moral relativism is unpopular among philosophers; many are quite critical of it, though there are several contemporary philosophers who support it.Meta-ethical moral relativists believe not only that people disagree about moral issues, but that terms such as "good", "bad", "right" and "wrong" do not stand subject to universal truth conditions at all; rather, they are relative to the traditions, convictions, or practices of an individual or a group of people. The American anthropologist William Graham Sumner was an influential advocate of this view. He argues in his 1906 work Folkways that what people consider right and wrong is shaped entirely - not primarily - by the traditions, customs, and practices of their culture. Moreover, since in his analysis of human understanding there cannot be any higher moral standard than that provided by the local morals of a culture, no trans-cultural judgement about the rightness or wrongness of a culture's morals could possibly be justified.

Meta-ethical relativists are, first, descriptive relativists: they believe that, given the same set of facts, some societies or individuals will have a fundamental disagreement about what a person ought to do or prefer (based on societal or individual norms). What's more, they argue that one cannot adjudicate these disagreements using any available independent standard of evaluation—any appeal to a relevant standard would always be merely personal or at best societal.

This view contrasts with moral universalism, which argues that, even though well-intentioned persons disagree, and some may even remain unpersuadable (e.g. someone who is closed-minded), there is still a meaningful sense in which an action could be more "moral" (morally preferable) than another; that is, they believe there are objective standards of evaluation that seem worth calling "moral facts"—regardless of whether they are universally accepted.

Normative

Normative moral relativists believe not only the meta-ethical thesis, but that it has normative implications on what we ought to do. They argue that meta-ethical relativism implies that we ought to tolerate the behavior of others even when it runs counter to our personal or cultural moral standards. Most philosophers do not agree, partially because of the challenges of arriving at an "ought" from relativistic premises. Meta-ethical relativism seems to eliminate the normative relativist's ability to make prescriptive claims. In other words, normative relativism may find it difficult to make a statement like "we think it is moral to tolerate behaviour" without always adding "other people think intolerance of certain behaviours is moral". Philosophers like Russell Blackford even argue that intolerance is, to some degree, important. As he puts it, "we need not adopt a quietism about moral traditions that cause hardship and suffering. Nor need we passively accept the moral norms of our own respective societies, to the extent that they are ineffective or counterproductive or simply unnecessary". That is, it is perfectly reasonable (and practical) for a person or group to defend their subjective values against others, even if there is no universal prescription or morality. We can also criticize other cultures for failing to pursue even their own goals effectively.The moral relativists may also still try to make sense of non-universal statements like "in this country, it is wrong to do X" or even "to me, it is right to do Y".

Moral universalists argue further that their system often does justify tolerance, and that disagreement with moral systems does not always demand interference, and certainly not aggressive interference. For example, the utilitarian might call another society's practice 'ignorant' or 'less moral', but there would still be much debate about courses of action (e.g. whether to focus on providing better education, or technology, etc.).

History

Moral relativism encompasses views and arguments that people in various cultures have held over several thousand years. For example, the ancient Jaina Anekantavada principle of Mahavira (c. 599–527 BC) states that truth and reality are perceived differently from diverse points of view, and that no single point of view is the complete truth; and the Greek philosopher Protagoras (c. 481–420 BC) famously asserted that "man is the measure of all things". The Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484–420 BC) observed that each society regards its own belief system and way of doing things as better than all others. Various other ancient philosophers also questioned the idea of an objective standard of morality.In the early modern era Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) notably held that nothing is inherently good or evil. The 18th-century Enlightenment philosopher David Hume (1711–1776) serves in several important respects as the father both of modern emotivism and of moral relativism, though Hume himself did not espouse relativism. He distinguished between matters of fact and matters of value, and suggested that moral judgments consist of the latter, for they do not deal with verifiable facts obtained in the world, but only with our sentiments and passions. But Hume regarded some of our sentiments as universal. He famously denied that morality has any objective standard, and suggested that the universe remains indifferent to our preferences and our troubles.

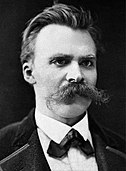

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) believed that we have to assess the value of our values since values are relative to one's goals and one's self. He emphasized the need to analyze our moral values and how much impact they may have on us. The problem with morality, according to Nietzsche, is that those who were considered "good" were the powerful nobles who had more education, and considered themselves better than anyone below their rank. Thus, what is considered good is relative. A "good man" is not questioned on whether or not there is a "bad", such as temptations, lingering inside him and he is considered to be more important than a man who is considered "bad" who is considered useless to making the human race better because of the morals we have subjected ourselves to. But since what is considered good and bad is relative, the importance and value we place on them should also be relative. He proposed that morality itself could be a danger. Nietzsche believed that morals should be constructed actively, making them relative to who we are and what we, as individuals, consider to be true, equal, good and bad, etc. instead of reacting to moral laws made by a certain group of individuals in power.

One scholar, supporting an anti-realist interpretation, concludes that "Nietzsche's central argument for anti-realism about value is explanatory: moral facts don't figure in the 'best explanation' of experience, and so are not real constituents of the objective world. Moral values, in short, can be 'explained away.'"

It is certain that Nietzsche criticizes Plato's prioritization of transcendence as the Forms. The Platonist view holds that what is 'true', or most real, is something which is other-worldly while the (real) world of experience is like a mere 'shadow' of the Forms, most famously expressed in Plato's allegory of the cave. Nietzsche believes that this transcendence also had a parallel growth in Christianity, which prioritized life-denying moral qualities such as humility and obedience through the church. (See Beyond Good and Evil, On the Genealogy of Morals, The Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist, etc.)

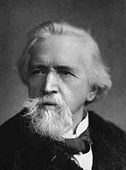

Anthropologists such as Ruth Benedict (1887–1948) have cautioned observers against ethnocentricism—using the standards of their own culture to evaluate their subjects of study. Benedict said that transcendent morals do not exist—only socially constructed customs do; and that in comparing customs, the anthropologist "insofar as he remains an anthropologist ... is bound to avoid any weighting of one in favor of the other". To some extent, the increasing body of knowledge of great differences in belief among societies caused both social scientists and philosophers to question whether any objective, absolute standards pertaining to values could exist. This led some to posit that differing systems have equal validity, with no standard for adjudicating among conflicting beliefs. The Finnish philosopher-anthropologist Edward Westermarck (1862–1939) ranks as one of the first to formulate a detailed theory of moral relativism. He portrayed all moral ideas as subjective judgments that reflect one's upbringing. He rejected G.E. Moore's (1873–1958) ethical intuitionism—in vogue during the early part of the 20th century, and which identified moral propositions as true or false, and known to us through a special faculty of intuition—because of the obvious differences in beliefs among societies, which he said provided evidence of the lack of any innate, intuitive power.

Views on meta-ethical relativism

Scientific

Morality and evolution

Some evolutionary biologists believe that morality is a natural phenomenon that evolves by natural selection. In this case, morality is defined as the set of relative social practices that promote the survival and successful reproduction of the species, or even multiple cooperating species.Philosophical

R. M. Hare

Some philosophers, for example R. M. Hare (1919–2002), argue that moral propositions remain subject to human logical rules, notwithstanding the absence of any factual content, including those subject to cultural or religious standards or norms. Thus, for example, they contend that one cannot hold contradictory ethical judgments. This allows for moral discourse with shared standards, notwithstanding the descriptive properties or truth conditions of moral terms. They do not affirm or deny that moral facts exist, only that human logic applies to our moral assertions; consequently, they postulate an objective and preferred standard of moral justification, albeit in a very limited sense. Nevertheless, according to Hare, human logic shows the error of relativism in one very important sense (see Hare's Sorting out Ethics). Hare and other philosophers also point out that, aside from logical constraints, all systems treat certain moral terms alike in an evaluative sense. This parallels our treatment of other terms such as less or more, which meet with universal understanding and do not depend upon independent standards (for example, one can convert measurements). It applies to good and bad when used in their non-moral sense, too; for example, when we say, "this is a good wrench" or "this is a bad wheel". This evaluative property of certain terms also allows people of different beliefs to have meaningful discussions on moral questions, even though they may disagree about certain "facts".Walter Terence Stace

"Ethical Relativity" is the topic of the first two chapters in The Concept of Morals, in which Walter Terence Stace argues against moral absolutism, but for moral universalism.Philosophical poverty

Critics propose that moral relativism fails because it rejects basic premises of discussions on morality, or because it cannot arbitrate disagreement. Many critics, including Ibn Warraq and Eddie Tabash, have suggested that meta-ethical relativists essentially take themselves out of any discussion of normative morality, since they seem to be rejecting an assumption of such discussions: the premise that there are right and wrong answers that can be discovered through reason. Practically speaking, such critics will argue that meta-ethical relativism may amount to moral nihilism, or else incoherence.These critics argue specifically that the moral relativists reduce the extent of their input in normative moral discussions to either rejecting the very having of the discussion, or else deeming both disagreeing parties to be correct. For instance, the moral relativist can only appeal to preference to object to the practice of murder or torture by individuals for hedonistic pleasure. This accusation that relativists reject widely held terms of discourse is similar to arguments used against other "discussion-stoppers" like some forms of solipsism or the rejection of induction.

Philosopher Simon Blackburn made a similar criticism, and explains that moral relativism fails as a moral system simply because it cannot arbitrate disagreements.

The moral relativist might respond that their conception of morality is more accurate given the provided cross cultural data and that it seems to hold true regardless of the counter arguments of the position's objectors. They also might argue that most moral arguments are a form of the logical fallacy "Begging the Question" because it assumed that the moral position being argued is already good and moral and people who argue to "prove" their moral position are assuming that the cultural moral norms that they already have are already true. The critics, however, maintain that their conception of morality is, for that exact reason, inadequate. Ultimately critics can do little more than to invite moral-relativists to re-define "morality" in practical or morally realistic terms.

Other criticism

Some arguments come when people question which moral justifications or truths are said to be relative. Because people belong to many groups based on culture, race, religion, etc., it is difficult to claim that the values of the group have authority for the members. A part of meta-ethical relativism is identifying which group of people those truths are relative to. Another component is that many people belong to more than one group. The beliefs of the groups that a person belongs to may be fundamentally different, and so it is hard to decide which are relative and which win out. A person practicing meta-ethical relativism would not necessarily object to either view, but develop an opinion and argument.Religious

Roman Catholicism

Catholic and some secular intellectuals attribute the perceived post-war decadence of Europe to the displacement of absolute values by moral relativism. Pope Benedict XVI, Marcello Pera and others have argued that after about 1960, Europeans massively abandoned many traditional norms rooted in Christianity and replaced them with continuously evolving relative moral rules. In this view, sexual activity has become separated from procreation, which led to a decline in the importance of families and to depopulation. As a result, currently the population vacuum in Europe is filled by immigrants, often from Islamic countries, who attempt to reestablish absolute values which stand at odds with moral relativism. The most authoritative response to moral relativism from the Roman Catholic perspective can be found in Veritatis Splendor, an encyclical by Pope John Paul II. Many of the main criticisms of moral relativism by the Catholic Church relate largely to modern controversies, such as elective abortion.Buddhism

Bhikkhu Bodhi, an American Buddhist monk, has written: "By assigning value and spiritual ideals to private subjectivity, the materialistic world view ... threatens to undermine any secure objective foundation for morality. The result is the widespread moral degeneration that we witness today. To counter this tendency, mere moral exhortation is insufficient. If morality is to function as an efficient guide to conduct, it cannot be propounded as a self-justifying scheme but must be embedded in a more comprehensive spiritual system which grounds morality in a transpersonal order. Religion must affirm, in the clearest terms, that morality and ethical values are not mere decorative frills of personal opinion, not subjective superstructure, but intrinsic laws of the cosmos built into the heart of reality."Literary

The literary perspectivism begins at the different versions of the Greek myths. Symbolism created multiple suggestions for a vers. Structuralism teaches us the polysemy of the poems.Examples of relativistic literary works: Gogol's Dead Souls; The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell; Raymond Queneau's Zazie dans le métro. Or Nuria Perpinya's twenty literary interpretations of the Odyssey.