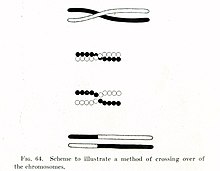

Figure 1. During meiosis, homologous recombination can produce new combinations of genes as shown here between similar but not identical copies of human chromosome 1

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which nucleotide sequences are exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of DNA. It is most widely used by cells to accurately repair harmful breaks that occur on both strands of DNA, known as double-strand breaks (DSB). Homologous recombination also produces new combinations of DNA sequences during meiosis, the process by which eukaryotes make gamete cells, like sperm and egg cells in animals. These new combinations of DNA represent genetic variation in offspring, which in turn enables populations to adapt during the course of evolution. Homologous recombination is also used in horizontal gene transfer to exchange genetic material between different strains and species of bacteria and viruses.

Although homologous recombination varies widely among different organisms and cell types, most forms involve the same basic steps. After a double-strand break occurs, sections of DNA around the 5' ends of the break are cut away in a process called resection. In the strand invasion step that follows, an overhanging 3' end of the broken DNA molecule then "invades" a similar or identical DNA molecule that is not broken. After strand invasion, the further sequence of events may follow either of two main pathways discussed below; the DSBR (double-strand break repair) pathway or the SDSA (synthesis-dependent strand annealing) pathway. Homologous recombination that occurs during DNA repair tends to result in non-crossover products, in effect restoring the damaged DNA molecule as it existed before the double-strand break.

Homologous recombination is conserved across all three domains of life as well as viruses, suggesting that it is a nearly universal biological mechanism. The discovery of genes for homologous recombination in protists—a diverse group of eukaryotic microorganisms—has been interpreted as evidence that meiosis emerged early in the evolution of eukaryotes. Since their dysfunction has been strongly associated with increased susceptibility to several types of cancer, the proteins that facilitate homologous recombination are topics of active research. Homologous recombination is also used in gene targeting, a technique for introducing genetic changes into target organisms. For their development of this technique, Mario Capecchi, Martin Evans and Oliver Smithies were awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine; Capecchi and Smithies independently discovered applications to mouse embryonic stem cells, however the highly conserved mechanisms underlying the DSB repair model, including uniform homologous integration of transformed DNA (gene therapy), were first shown in plasmid experiments by Orr-Weaver, Szostack and Rothstein. Researching the plasmid-induced DSB, using γ-irradiation in the 1970s-1980s, led to later experiments using endonucleases (e.g. I-SceI) to cut chromosomes for genetic engineering of mammalian cells, where nonhomologous recombination is more frequent than in yeast.

History and discovery

Figure 2. An early illustration of crossing over from Thomas Hunt Morgan

In the early 1900s, William Bateson and Reginald Punnett found an exception to one of the principles of inheritance originally described by Gregor Mendel in the 1860s. In contrast to Mendel's notion that traits are independently assorted when passed from parent to child—for example that a cat's hair color and its tail length are inherited independent of each other—Bateson and Punnett showed that certain genes associated with physical traits can be inherited together, or genetically linked. In 1911, after observing that linked traits could on occasion be inherited separately, Thomas Hunt Morgan suggested that "crossovers" can occur between linked genes, where one of the linked genes physically crosses over to a different chromosome. Two decades later, Barbara McClintock and Harriet Creighton demonstrated that chromosomal crossover occurs during meiosis, the process of cell division by which sperm and egg cells are made. Within the same year as McClintock's discovery, Curt Stern showed that crossing over—later called "recombination"—could also occur in somatic cells like white blood cells and skin cells that divide through mitosis.

In 1947, the microbiologist Joshua Lederberg showed that bacteria—which had been assumed to reproduce only asexually through binary fission—are capable of genetic recombination, which is more similar to sexual reproduction. This work established E. coli as a model organism in genetics, and helped Lederberg win the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Building on studies in fungi, in 1964 Robin Holliday proposed a model for recombination in meiosis which introduced key details of how the process can work, including the exchange of material between chromosomes through Holliday junctions. In 1983, Jack Szostak and colleagues presented a model now known as the DSBR pathway, which accounted for observations not explained by the Holliday model. During the next decade, experiments in Drosophila, budding yeast and mammalian cells led to the emergence of other models of homologous recombination, called SDSA pathways, which do not always rely on Holliday junctions.

Much of the later work identifying proteins involved in the process and determining their mechanisms has been performed by a number of individuals including James Haber, Patrick Sung, Stephen Kowalczykowski, and others.

In eukaryotes

Homologous recombination (HR) is essential to cell division in eukaryotes like plants, animals, fungi and protists. In cells that divide through mitosis, homologous recombination repairs double-strand breaks in DNA caused by ionizing radiation or DNA-damaging chemicals. Left unrepaired, these double-strand breaks can cause large-scale rearrangement of chromosomes in somatic cells, which can in turn lead to cancer.In addition to repairing DNA, homologous recombination also helps produce genetic diversity when cells divide in meiosis to become specialized gamete cells—sperm or egg cells in animals, pollen or ovules in plants, and spores in fungi. It does so by facilitating chromosomal crossover, in which regions of similar but not identical DNA are exchanged between homologous chromosomes. This creates new, possibly beneficial combinations of genes, which can give offspring an evolutionary advantage. Chromosomal crossover often begins when a protein called Spo11 makes a targeted double-strand break in DNA. These sites are non-randomly located on the chromosomes; usually in intergenic promoter regions and preferentially in GC-rich domains These double-strand break sites often occur at recombination hotspots, regions in chromosomes that are about 1,000–2,000 base pairs in length and have high rates of recombination. The absence of a recombination hotspot between two genes on the same chromosome often means that those genes will be inherited by future generations in equal proportion. This represents linkage between the two genes greater than would be expected from genes that independently assort during meiosis.

Timing within the mitotic cell cycle

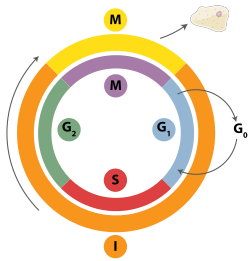

Figure 3. Homologous recombination repairs DNA before the cell enters mitosis (M phase). It occurs only during and shortly after DNA replication, during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle

Double-strand breaks can be repaired through homologous recombination or through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). NHEJ is a DNA repair mechanism which, unlike homologous recombination, does not require a long homologous sequence to guide repair. Whether homologous recombination or NHEJ is used to repair double-strand breaks is largely determined by the phase of cell cycle. Homologous recombination repairs DNA before the cell enters mitosis (M phase). It occurs during and shortly after DNA replication, in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, when sister chromatids are more easily available. Compared to homologous chromosomes, which are similar to another chromosome but often have different alleles, sister chromatids are an ideal template for homologous recombination because they are an identical copy of a given chromosome. In contrast to homologous recombination, NHEJ is predominant in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, when the cell is growing but not yet ready to divide. It occurs less frequently after the G1 phase, but maintains at least some activity throughout the cell cycle. The mechanisms that regulate homologous recombination and NHEJ throughout the cell cycle vary widely between species.

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), which modify the activity of other proteins by adding phosphate groups to (that is, phosphorylating) them, are important regulators of homologous recombination in eukaryotes. When DNA replication begins in budding yeast, the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc28 begins homologous recombination by phosphorylating the Sae2 protein. After being so activated by the addition of a phosphate, Sae2 uses its endonuclease activity to make a clean cut near a double-strand break in DNA. This allows a three-part protein known as the MRX complex to bind to DNA, and begins a series of protein-driven reactions that exchange material between two DNA molecules.

Preliminary steps

The packaging of eukaryotic DNA into chromatin presents a barrier to all DNA-based processes that require recruitment of enzymes to their sites of action. To allow HR DNA repair, the chromatin must be remodeled. In eukaryotes, ATP dependent chromatin remodeling complexes and histone-modifying enzymes are two predominant factors employed to accomplish this remodeling process.Chromatin relaxation occurs rapidly at the site of a DNA damage. In one of the earliest steps, the stress-activated protein kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), phosphorylates SIRT6 on serine 10 in response to double-strand breaks or other DNA damage. This post-translational modification facilitates the mobilization of SIRT6 to DNA damage sites, and is required for efficient recruitment of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) to DNA break sites and for efficient repair of DSBs. PARP1 protein starts to appear at DNA damage sites in less than a second, with half maximum accumulation within 1.6 seconds after the damage occurs. Next the chromatin remodeler Alc1 quickly attaches to the product of PARP1 action, a poly-ADP ribose chain, and Alc1 completes arrival at the DNA damage within 10 seconds of the occurrence of the damage. About half of the maximum chromatin relaxation, presumably due to action of Alc1, occurs by 10 seconds. This then allows recruitment of the DNA repair enzyme MRE11, to initiate DNA repair, within 13 seconds.

γH2AX, the phosphorylated form of H2AX is also involved in the early steps leading to chromatin decondensation after DNA double-strand breaks. The histone variant H2AX constitutes about 10% of the H2A histones in human chromatin. γH2AX (H2AX phosphorylated on serine 139) can be detected as soon as 20 seconds after irradiation of cells (with DNA double-strand break formation), and half maximum accumulation of γH2AX occurs in one minute. The extent of chromatin with phosphorylated γH2AX is about two million base pairs at the site of a DNA double-strand break. γH2AX does not, itself, cause chromatin decondensation, but within 30 seconds of irradiation, RNF8 protein can be detected in association with γH2AX. RNF8 mediates extensive chromatin decondensation, through its subsequent interaction with CHD4, a component of the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase complex NuRD.

After undergoing relaxation subsequent to DNA damage, followed by DNA repair, chromatin recovers to a compaction state close to its pre-damage level after about 20 min.

Models

Two primary models for how homologous recombination repairs double-strand breaks in DNA are the double-strand break repair (DSBR) pathway (sometimes called the double Holliday junction model) and the synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) pathway. The two pathways are similar in their first several steps. After a double-strand break occurs, the MRX complex (MRN complex in humans) binds to DNA on either side of the break. Next a resection, in which DNA around the 5' ends of the break is cut back, is carried out in two distinct steps. In the first step of resection, the MRX complex recruits the Sae2 protein. The two proteins then trim back the 5' ends on either side of the break to create short 3' overhangs of single-strand DNA. In the second step, 5'→3' resection is continued by the Sgs1 helicase and the Exo1 and Dna2 nucleases. As a helicase, Sgs1 "unzips" the double-strand DNA, while Exo1 and Dna2's nuclease activity allows them to cut the single-stranded DNA produced by Sgs1.

Figure 4.

The DSBR and SDSA pathways follow the same initial steps, but diverge

thereafter. The DSBR pathway most often results in chromosomal crossover

(bottom left), while SDSA always ends with non-crossover products

(bottom right)

The RPA protein, which has high affinity for single-stranded DNA, then binds the 3' overhangs. With the help of several other proteins that mediate the process, the Rad51 protein (and Dmc1, in meiosis) then forms a filament of nucleic acid and protein on the single strand of DNA coated with RPA. This nucleoprotein filament then begins searching for DNA sequences similar to that of the 3' overhang. After finding such a sequence, the single-stranded nucleoprotein filament moves into (invades) the similar or identical recipient DNA duplex in a process called strand invasion. In cells that divide through mitosis, the recipient DNA duplex is generally a sister chromatid, which is identical to the damaged DNA molecule and provides a template for repair. In meiosis, however, the recipient DNA tends to be from a similar but not necessarily identical homologous chromosome. A displacement loop (D-loop) is formed during strand invasion between the invading 3' overhang strand and the homologous chromosome. After strand invasion, a DNA polymerase extends the end of the invading 3' strand by synthesizing new DNA. This changes the D-loop to a cross-shaped structure known as a Holliday junction. Following this, more DNA synthesis occurs on the invading strand (i.e., one of the original 3' overhangs), effectively restoring the strand on the homologous chromosome that was displaced during strand invasion.

DSBR pathway

After the stages of resection, strand invasion and DNA synthesis, the DSBR and SDSA pathways become distinct. The DSBR pathway is unique in that the second 3' overhang (which was not involved in strand invasion) also forms a Holliday junction with the homologous chromosome. The double Holliday junctions are then converted into recombination products by nicking endonucleases, a type of restriction endonuclease which cuts only one DNA strand. The DSBR pathway commonly results in crossover, though it can sometimes result in non-crossover products; the ability of a broken DNA molecule to collect sequences from separated donor loci was shown in mitotic budding yeast using plasmids or endonuclease induction of chromosomal events. Because of this tendency for chromosomal crossover, the DSBR pathway is a likely model of how crossover homologous recombination occurs during meiosis.Whether recombination in the DSBR pathway results in chromosomal crossover is determined by how the double Holliday junction is cut, or "resolved". Chromosomal crossover will occur if one Holliday junction is cut on the crossing strand and the other Holliday junction is cut on the non-crossing strand (in Figure 4, along the horizontal purple arrowheads at one Holliday junction and along the vertical orange arrowheads at the other). Alternatively, if the two Holliday junctions are cut on the crossing strands (along the horizontal purple arrowheads at both Holliday junctions in Figure 4), then chromosomes without crossover will be produced.

SDSA pathway

Homologous recombination via the SDSA pathway occurs in cells that divide through mitosis and meiosis and results in non-crossover products. In this model, the invading 3' strand is extended along the recipient DNA duplex by a DNA polymerase, and is released as the Holliday junction between the donor and recipient DNA molecules slides in a process called branch migration. The newly synthesized 3' end of the invading strand is then able to anneal to the other 3' overhang in the damaged chromosome through complementary base pairing. After the strands anneal, a small flap of DNA can sometimes remain. Any such flaps are removed, and the SDSA pathway finishes with the resealing, also known as ligation, of any remaining single-stranded gaps.During mitosis, the major homologous recombination pathway for repairing DNA double-strand breaks appears to be the SDSA pathway (rather than the DSBR pathway). The SDSA pathway produces non-crossover recombinants (Figure 4). During meiosis non-crossover recombinants also occur frequently and these appear to arise mainly by the SDSA pathway as well. Non-crossover recombination events occurring during meiosis likely reflect instances of repair of DNA double-strand damages or other types of DNA damages.

SSA pathway

The single-strand annealing (SSA) pathway of homologous recombination repairs double-strand breaks between two repeat sequences. The SSA pathway is unique in that it does not require a separate similar or identical molecule of DNA, like the DSBR or SDSA pathways of homologous recombination. Instead, the SSA pathway only requires a single DNA duplex, and uses the repeat sequences as the identical sequences that homologous recombination needs for repair. The pathway is relatively simple in concept: after two strands of the same DNA duplex are cut back around the site of the double-strand break, the two resulting 3' overhangs then align and anneal to each other, restoring the DNA as a continuous duplex.

As DNA around the double-strand break is cut back, the single-stranded 3' overhangs being produced are coated with the RPA protein, which prevents the 3' overhangs from sticking to themselves. A protein called Rad52 then binds each of the repeat sequences on either side of the break, and aligns them to enable the two complementary repeat sequences to anneal. After annealing is complete, leftover non-homologous flaps of the 3' overhangs are cut away by a set of nucleases, known as Rad1/Rad10, which are brought to the flaps by the Saw1 and Slx4 proteins. New DNA synthesis fills in any gaps, and ligation restores the DNA duplex as two continuous strands. The DNA sequence between the repeats is always lost, as is one of the two repeats. The SSA pathway is considered mutagenic since it results in such deletions of genetic material.

BIR pathway

During DNA replication, double-strand breaks can sometimes be encountered at replication forks as DNA helicase unzips the template strand. These defects are repaired in the break-induced replication (BIR) pathway of homologous recombination. The precise molecular mechanisms of the BIR pathway remain unclear. Three proposed mechanisms have strand invasion as an initial step, but they differ in how they model the migration of the D-loop and later phases of recombination.The BIR pathway can also help to maintain the length of telomeres (regions of DNA at the end of eukaryotic chromosomes) in the absence of (or in cooperation with) telomerase. Without working copies of the enzyme telomerase, telomeres typically shorten with each cycle of mitosis, which eventually blocks cell division and leads to senescence. In budding yeast cells where telomerase has been inactivated through mutations, two types of "survivor" cells have been observed to avoid senescence longer than expected by elongating their telomeres through BIR pathways.

Maintaining telomere length is critical for cell immortalization, a key feature of cancer. Most cancers maintain telomeres by upregulating telomerase. However, in several types of human cancer, a BIR-like pathway helps to sustain some tumors by acting as an alternative mechanism of telomere maintenance. This fact has led scientists to investigate whether such recombination-based mechanisms of telomere maintenance could thwart anti-cancer drugs like telomerase inhibitors.

In bacteria

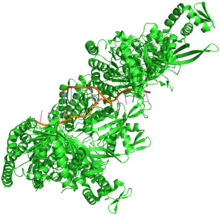

Figure 6. Crystal structure of a RecA protein filament bound to DNA.[53] A 3' overhang is visible to the right of center.

Homologous recombination is a major DNA repair process in bacteria. It is also important for producing genetic diversity in bacterial populations, although the process differs substantially from meiotic recombination, which repairs DNA damages and brings about diversity in eukaryotic genomes. Homologous recombination has been most studied and is best understood for Escherichia coli. Double-strand DNA breaks in bacteria are repaired by the RecBCD pathway of homologous recombination. Breaks that occur on only one of the two DNA strands, known as single-strand gaps, are thought to be repaired by the RecF pathway. Both the RecBCD and RecF pathways include a series of reactions known as branch migration, in which single DNA strands are exchanged between two intercrossed molecules of duplex DNA, and resolution, in which those two intercrossed molecules of DNA are cut apart and restored to their normal double-stranded state.

RecBCD pathway

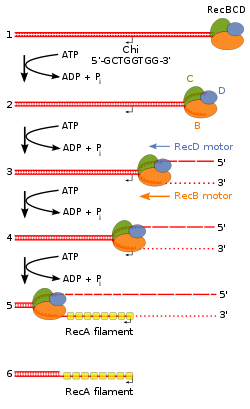

Figure 7A.

Molecular model for the RecBCD pathway of recombination. This model is

based on reactions of DNA and RecBCD with ATP in excess over Mg2+ ions.

Step 1: RecBCD binds to a double-stranded DNA end. Step 2: RecBCD

unwinds DNA. RecD is a fast helicase on the 5’-ended strand, and RecB

is a slower helicase on the 3'-ended strand (that with an arrowhead)

[ref 46 in current Wiki version]. This produces two single-stranded

(ss) DNA tails and one ss loop. The loop and tails enlarge as RecBCD

moves along the DNA. Step 3: The two tails anneal to produce a second

ss DNA loop, and both loops move and grow. Step 4: Upon reaching the

Chi hotspot sequence (5' GCTGGTGG 3'; red dot) RecBCD nicks the 3’-ended

strand. Further unwinding produces a long 3'-ended ss tail with Chi

near its end. Step 5: RecBCD loads RecA protein onto the Chi tail. At

some undetermined point, the RecBCD subunits disassemble. Step 6: The

RecA-ssDNA complex invades an intact homologous duplex DNA to produce a

D-loop, which can be resolved into intact, recombinant DNA in two ways.

Step 7: The D-loop is cut and anneals with the gap in the first DNA

to produce a Holliday junction. Resolution of the Holliday junction

(cutting, swapping of strands, and ligation) at the open arrowheads by

some combination of RuvABC and RecG produces two recombinants of

reciprocal type. Step 8: The 3' end of the Chi tail primes DNA

synthesis, from which a replication fork can be generated. Resolution

of the fork at the open arrowheads produces one recombinant

(non-reciprocal) DNA, one parental-type DNA, and one DNA fragment.

Figure 7B. Beginning of the RecBCD pathway. This model is based on reactions of DNA and RecBCD with Mg2+

ions in excess over ATP. Step 1: RecBCD binds to a DNA double strand

break. Step 2: RecBCD initiates unwinding of the DNA duplex through

ATP-dependent helicase

activity. Step 3: RecBCD continues its unwinding and moves down the

DNA duplex, cleaving the 3' strand much more frequently than the 5'

strand. Step 4: RecBCD encounters a Chi sequence

and stops digesting the 3' strand; cleavage of the 5' strand is

significantly increased. Step 5: RecBCD loads RecA onto the 3' strand.

Step 6: RecBCD unbinds from the DNA duplex, leaving a RecA nucleoprotein

filament on the 3' tail.

The RecBCD pathway is the main recombination pathway used in many bacteria to repair double-strand breaks in DNA, and the proteins are found in a broad array of bacteria.[58][59][60] These double-strand breaks can be caused by UV light and other radiation, as well as chemical mutagens. Double-strand breaks may also arise by DNA replication through a single-strand nick or gap. Such a situation causes what is known as a collapsed replication fork and is fixed by several pathways of homologous recombination including the RecBCD pathway.

In this pathway, a three-subunit enzyme complex called RecBCD initiates recombination by binding to a blunt or nearly blunt end of a break in double-strand DNA. After RecBCD binds the DNA end, the RecB and RecD subunits begin unzipping the DNA duplex through helicase activity. The RecB subunit also has a nuclease domain, which cuts the single strand of DNA that emerges from the unzipping process. This unzipping continues until RecBCD encounters a specific nucleotide sequence (5'-GCTGGTGG-3') known as a Chi site.

Upon encountering a Chi site, the activity of the RecBCD enzyme changes drastically. DNA unwinding pauses for a few seconds and then resumes at roughly half the initial speed. This is likely because the slower RecB helicase unwinds the DNA after Chi, rather than the faster RecD helicase, which unwinds the DNA before Chi. Recognition of the Chi site also changes the RecBCD enzyme so that it cuts the DNA strand with Chi and begins loading multiple RecA proteins onto the single-stranded DNA with the newly generated 3' end. The resulting RecA-coated nucleoprotein filament then searches out similar sequences of DNA on a homologous chromosome. The search process induces stretching of the DNA duplex, which enhances homology recognition (a mechanism termed conformational proofreading). Upon finding such a sequence, the single-stranded nucleoprotein filament moves into the homologous recipient DNA duplex in a process called strand invasion. The invading 3' overhang causes one of the strands of the recipient DNA duplex to be displaced, to form a D-loop. If the D-loop is cut, another swapping of strands forms a cross-shaped structure called a Holliday junction. Resolution of the Holliday junction by some combination of RuvABC or RecG can produce two recombinant DNA molecules with reciprocal genetic types, if the two interacting DNA molecules differ genetically. Alternatively, the invading 3’ end near Chi can prime DNA synthesis and form a replication fork. This type of resolution produces only one type of recombinant (non-reciprocal).

RecF pathway

Bacteria appear to use the RecF pathway of homologous recombination to repair single-strand gaps in DNA. When the RecBCD pathway is inactivated by mutations and additional mutations inactivate the SbcCD and ExoI nucleases, the RecF pathway can also repair DNA double-strand breaks. In the RecF pathway the RecQ helicase unwinds the DNA and the RecJ nuclease degrades the strand with a 5' end, leaving the strand with the 3' end intact. RecA protein binds to this strand and is either aided by the RecF, RecO, and RecR proteins or stabilized by them. The RecA nucleoprotein filament then searches for a homologous DNA and exchanges places with the identical or nearly identical strand in the homologous DNA.Although the proteins and specific mechanisms involved in their initial phases differ, the two pathways are similar in that they both require single-stranded DNA with a 3' end and the RecA protein for strand invasion. The pathways are also similar in their phases of branch migration, in which the Holliday junction slides in one direction, and resolution, in which the Holliday junctions are cleaved apart by enzymes. The alternative, non-reciprocal type of resolution may also occur by either pathway.

Branch migration

Immediately after strand invasion, the Holliday junction moves along the linked DNA during the branch migration process. It is in this movement of the Holliday junction that base pairs between the two homologous DNA duplexes are exchanged. To catalyze branch migration, the RuvA protein first recognizes and binds to the Holliday junction and recruits the RuvB protein to form the RuvAB complex. Two sets of the RuvB protein, which each form a ring-shaped ATPase, are loaded onto opposite sides of the Holliday junction, where they act as twin pumps that provide the force for branch migration. Between those two rings of RuvB, two sets of the RuvA protein assemble in the center of the Holliday junction such that the DNA at the junction is sandwiched between each set of RuvA. The strands of both DNA duplexes—the "donor" and the "recipient" duplexes—are unwound on the surface of RuvA as they are guided by the protein from one duplex to the other.Resolution

In the resolution phase of recombination, any Holliday junctions formed by the strand invasion process are cut, thereby restoring two separate DNA molecules. This cleavage is done by RuvAB complex interacting with RuvC, which together form the RuvABC complex. RuvC is an endonuclease that cuts the degenerate sequence 5'-(A/T)TT(G/C)-3'. The sequence is found frequently in DNA, about once every 64 nucleotides. Before cutting, RuvC likely gains access to the Holliday junction by displacing one of the two RuvA tetramers covering the DNA there. Recombination results in either "splice" or "patch" products, depending on how RuvC cleaves the Holliday junction. Splice products are crossover products, in which there is a rearrangement of genetic material around the site of recombination. Patch products, on the other hand, are non-crossover products in which there is no such rearrangement and there is only a "patch" of hybrid DNA in the recombination product.Facilitating genetic transfer

Homologous recombination is an important method of integrating donor DNA into a recipient organism's genome in horizontal gene transfer, the process by which an organism incorporates foreign DNA from another organism without being the offspring of that organism. Homologous recombination requires incoming DNA to be highly similar to the recipient genome, and so horizontal gene transfer is usually limited to similar bacteria. Studies in several species of bacteria have established that there is a log-linear decrease in recombination frequency with increasing difference in sequence between host and recipient DNA.In bacterial conjugation, where DNA is transferred between bacteria through direct cell-to-cell contact, homologous recombination helps integrate foreign DNA into the host genome via the RecBCD pathway. The RecBCD enzyme promotes recombination after DNA is converted from single-strand DNA–in which form it originally enters the bacterium–to double-strand DNA during replication. The RecBCD pathway is also essential for the final phase of transduction, a type of horizontal gene transfer in which DNA is transferred from one bacterium to another by a virus. Foreign, bacterial DNA is sometimes misincorporated in the capsid head of bacteriophage virus particles as DNA is packaged into new bacteriophages during viral replication. When these new bacteriophages infect other bacteria, DNA from the previous host bacterium is injected into the new bacterial host as double-strand DNA. The RecBCD enzyme then incorporates this double-strand DNA into the genome of the new bacterial host.

Bacterial transformation

Natural bacterial transformation involves the transfer of DNA from a donor bacterium to a recipient bacterium, where both donor and recipient are ordinarily of the same species. Transformation, unlike bacterial conjugation and transduction, depends on numerous bacterial gene products that specifically interact to perform this process. Thus transformation is clearly a bacterial adaptation for DNA transfer. In order for a bacterium to bind, take up and integrate donor DNA into its resident chromosome by homologous recombination, it must first enter a special physiological state termed competence. The RecA/Rad51/DMC1 gene family plays a central role in homologous recombination during bacterial transformation as it does during eukaryotic meiosis and mitosis. For instance, the RecA protein is essential for transformation in Bacillus subtilis and Streptococcus pneumoniae, and expression of the RecA gene is induced during the development of competence for transformation in these organisms.As part of the transformation process, the RecA protein interacts with entering single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) to form RecA/ssDNA nucleofilaments that scan the resident chromosome for regions of homology and bring the entering ssDNA to the corresponding region, where strand exchange and homologous recombination occur. Thus the process of homologous recombination during bacterial transformation has fundamental similarities to homologous recombination during meiosis.

In viruses

Homologous recombination occurs in several groups of viruses. In DNA viruses such as herpesvirus, recombination occurs through a break-and-rejoin mechanism like in bacteria and eukaryotes. There is also evidence for recombination in some RNA viruses, specifically positive-sense ssRNA viruses like retroviruses, picornaviruses, and coronaviruses. There is controversy over whether homologous recombination occurs in negative-sense ssRNA viruses like influenza.In RNA viruses, homologous recombination can be either precise or imprecise. In the precise type of RNA-RNA recombination, there is no difference between the two parental RNA sequences and the resulting crossover RNA region. Because of this, it is often difficult to determine the location of crossover events between two recombining RNA sequences. In imprecise RNA homologous recombination, the crossover region has some difference with the parental RNA sequences – caused by either addition, deletion, or other modification of nucleotides. The level of precision in crossover is controlled by the sequence context of the two recombining strands of RNA: sequences rich in adenine and uracil decrease crossover precision.

Homologous recombination is important in facilitating viral evolution. For example, if the genomes of two viruses with different disadvantageous mutations undergo recombination, then they may be able to regenerate a fully functional genome. Alternatively, if two similar viruses have infected the same host cell, homologous recombination can allow those two viruses to swap genes and thereby evolve more potent variations of themselves.

Homologous recombination is the proposed mechanism whereby the DNA virus human herpesvirus-6 integrates into human telomeres.

When two or more viruses, each containing lethal genomic damage, infect the same host cell, the virus genomes can often pair with each other and undergo homologous recombinational repair to produce viable progeny. This process, known as multiplicity reactivation, has been studied in several bacteriophages, including phage T4. Enzymes employed in recombinational repair in phage T4 are functionally homologous to enzymes employed in bacterial and eukaryotic recombinational repair. In particular, with regard to a gene necessary for the strand exchange reaction, a key step in homologous recombinational repair, there is functional homology from viruses to humans (i. e. uvsX in phage T4; recA in E. coli and other bacteria, and rad51 and dmc1 in yeast and other eukaryotes, including humans). Multiplicity reactivation has also been demonstrated in numerous pathogenic viruses.

Effects of dysfunction

Without proper homologous recombination, chromosomes often incorrectly align for the first phase of cell division in meiosis. This causes chromosomes to fail to properly segregate in a process called nondisjunction. In turn, nondisjunction can cause sperm and ova to have too few or too many chromosomes. Down's syndrome, which is caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21, is one of many abnormalities that result from such a failure of homologous recombination in meiosis.Deficiencies in homologous recombination have been strongly linked to cancer formation in humans. For example, each of the cancer-related diseases Bloom's syndrome, Werner's syndrome and Rothmund-Thomson syndrome are caused by malfunctioning copies of RecQ helicase genes involved in the regulation of homologous recombination: BLM, WRN and RECQL4, respectively. In the cells of Bloom's syndrome patients, who lack a working copy of the BLM protein, there is an elevated rate of homologous recombination. Experiments in mice deficient in BLM have suggested that the mutation gives rise to cancer through a loss of heterozygosity caused by increased homologous recombination. A loss in heterozygosity refers to the loss of one of two versions—or alleles—of a gene. If one of the lost alleles helps to suppress tumors, like the gene for the retinoblastoma protein for example, then the loss of heterozygosity can lead to cancer.

Decreased rates of homologous recombination cause inefficient DNA repair, which can also lead to cancer. This is the case with BRCA1 and BRCA2, two similar tumor suppressor genes whose malfunctioning has been linked with considerably increased risk for breast and ovarian cancer. Cells missing BRCA1 and BRCA2 have a decreased rate of homologous recombination and increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation, suggesting that decreased homologous recombination leads to increased susceptibility to cancer. Because the only known function of BRCA2 is to help initiate homologous recombination, researchers have speculated that more detailed knowledge of BRCA2's role in homologous recombination may be the key to understanding the causes of breast and ovarian cancer.

Tumours with a homologous recombination deficiency (including BRCA defects) are described as HRD-positive.

Evolutionary conservation

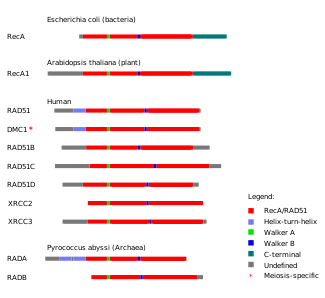

Figure 8. Protein domains in homologous recombination-related proteins are conserved across the three main groups of life: archaea, bacteria and eukaryotes.

While the pathways can mechanistically vary, the ability of organisms to perform homologous recombination is universally conserved across all domains of life. Based on the similarity of their amino acid sequences, homologs of a number of proteins can be found in multiple domains of life indicating that they evolved a long time ago, and have since diverged from common ancestral proteins.

RecA recombinase family members are found in almost all organisms with RecA in bacteria, Rad51 and DMC1 in eukaryotes, RadA in archaea, and UvsX in T4 phage.

Related single stranded binding proteins that are important for homologous recombination, and many other processes, are also found in all domains of life.

Rad54, Mre11, Rad50, and a number of other proteins are also found in both archaea and eukaryotes.

The RecA recombinase family

The proteins of the RecA recombinase family of proteins are thought to be descended from a common ancestral recombinase. The RecA recombinase family contains RecA protein from bacteria, the Rad51 and Dmc1 proteins from eukaryotes, and RadA from archaea, and the recombinase paralog proteins. Studies modeling the evolutionary relationships between the Rad51, Dmc1 and RadA proteins indicate that they are monophyletic, or that they share a common molecular ancestor. Within this protein family, Rad51 and Dmc1 are grouped together in a separate clade from RadA. One of the reasons for grouping these three proteins together is that they all possess a modified helix-turn-helix motif, which helps the proteins bind to DNA, toward their N-terminal ends. An ancient gene duplication event of a eukaryotic RecA gene and subsequent mutation has been proposed as a likely origin of the modern RAD51 and DMC1 genes.The proteins generally share a long conserved region known as the RecA/Rad51 domain. Within this protein domain are two sequence motifs, Walker A motif and Walker B motif. The Walker A and B motifs allow members of the RecA/Rad51 protein family to engage in ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis.

Meiosis-specific proteins

The discovery of Dmc1 in several species of Giardia, one of the earliest protists to diverge as a eukaryote, suggests that meiotic homologous recombination—and thus meiosis itself—emerged very early in eukaryotic evolution. In addition to research on Dmc1, studies on the Spo11 protein have provided information on the origins of meiotic recombination. Spo11, a type II topoisomerase, can initiate homologous recombination in meiosis by making targeted double-strand breaks in DNA. Phylogenetic trees based on the sequence of genes similar to SPO11 in animals, fungi, plants, protists and archaea have led scientists to believe that the version Spo11 currently in eukaryotes emerged in the last common ancestor of eukaryotes and archaea.Technological applications

Gene targeting

Figure 9. As a developing embryo, this chimeric mouse had the agouti coat color gene introduced into its DNA via gene targeting. Its offspring are homozygous for the agouti gene.

Many methods for introducing DNA sequences into organisms to create recombinant DNA and genetically modified organisms use the process of homologous recombination. Also called gene targeting, the method is especially common in yeast and mouse genetics. The gene targeting method in knockout mice uses mouse embryonic stem cells to deliver artificial genetic material (mostly of therapeutic interest), which represses the target gene of the mouse by the principle of homologous recombination. The mouse thereby acts as a working model to understand the effects of a specific mammalian gene. In recognition of their discovery of how homologous recombination can be used to introduce genetic modifications in mice through embryonic stem cells, Mario Capecchi, Martin Evans and Oliver Smithies were awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine.

Advances in gene targeting technologies which hijack the homologous recombination mechanics of cells are now leading to the development of a new wave of more accurate, isogenic human disease models. These engineered human cell models are thought to more accurately reflect the genetics of human diseases than their mouse model predecessors. This is largely because mutations of interest are introduced into endogenous genes, just as they occur in the real patients, and because they are based on human genomes rather than rat genomes. Furthermore, certain technologies enable the knock-in of a particular mutation rather than just knock-outs associated with older gene targeting technologies.

Protein engineering

Protein engineering with homologous recombination develops chimeric proteins by swapping fragments between two parental proteins. These techniques exploit the fact that recombination can introduce a high degree of sequence diversity while preserving a protein's ability to fold into its tertiary structure, or three-dimensional shape. This stands in contrast to other protein engineering techniques, like random point mutagenesis, in which the probability of maintaining protein function declines exponentially with increasing amino acid substitutions. The chimeras produced by recombination techniques are able to maintain their ability to fold because their swapped parental fragments are structurally and evolutionarily conserved. These recombinable "building blocks" preserve structurally important interactions like points of physical contact between different amino acids in the protein's structure. Computational methods like SCHEMA and statistical coupling analysis can be used to identify structural subunits suitable for recombination.Techniques that rely on homologous recombination have been used to engineer new proteins. In a study published in 2007, researchers were able to create chimeras of two enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of isoprenoids, a diverse class of compounds including hormones, visual pigments and certain pheromones. The chimeric proteins acquired an ability to catalyze an essential reaction in isoprenoid biosynthesis—one of the most diverse pathways of biosynthesis found in nature—that was absent in the parent proteins. Protein engineering through recombination has also produced chimeric enzymes with new function in members of a group of proteins known as the cytochrome P450 family, which in humans is involved in detoxifying foreign compounds like drugs, food additives and preservatives.