From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

History of anthropology in this article refers primarily to

the 18th- and 19th-century precursors of modern anthropology. The term

anthropology itself, innovated as a New Latin scientific word during the Renaissance,

has always meant "the study (or science) of man". The topics to be

included and the terminology have varied historically. At present they

are more elaborate than they were during the development of

anthropology. For a presentation of modern social and cultural

anthropology as they have developed in Britain, France, and North

America since approximately 1900, see the relevant sections under Anthropology.

Etymology

The mixed character of Greek anthropos and Latin -logia marks it as New Latin. There is no independent noun, logia, however, of that meaning in classical Greek. The word λόγος (logos) has that meaning. James Hunt attempted to rescue the etymology in his first address to the Anthropological Society of London as president and founder, 1863. He did find an anthropologos from Aristotle in the standard ancient Greek Lexicon, which he says defines the word as "speaking or treating of man". This view is entirely wishful thinking, as Liddell and Scott go on to explain the meaning: "i.e. fond of personal conversation". If Aristotle, the very philosopher of the logos, could produce such a word without serious intent, there probably was at that time no anthropology identifiable under that name.

The lack of any ancient denotation of anthropology, however, is not an etymological problem. Liddell and Scott list 170 Greek compounds ending in –logia, enough to justify its later use as a productive suffix. The ancient Greeks often used suffixes in forming compounds that had no independent variant. The etymological dictionaries are united in attributing –logia to logos, from legein, "to collect". The thing collected is primarily ideas, especially in speech. The American Heritage Dictionary says: "(It is one of) derivatives independently built to logos." Its morphological type is that of an abstract noun: log-os > log-ia (a "qualitative abstract")

The Renaissance origin of the name of anthropology does not exclude the possibility that ancient authors presented anthropogical material under another name (see below). Such an identification is speculative, depending on the theorist's view of anthropology; nevertheless, speculations have been formulated by credible anthropologists, especially those that consider themselves functionalists and others in history so classified now.

The science of history

Marvin Harris, a historian of anthropology, begins The Rise of Anthropological Theory with the statement that anthropology is "the science of history". He is not suggesting that history be renamed to anthropology, or that there is no distinction between history and prehistory, or that anthropology excludes current social practices, as the general meaning of history, which it has in "history of anthropology", would seem to imply. He is using "history" in a special sense, as the founders of cultural anthropology used it: "the natural history of society", in the words of Herbert Spencer, or the "universal history of mankind", the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment objective. Just as natural history comprises the characteristics of organisms past and present, so cultural or social history comprises the characteristics of society past and present. It includes both documented history and prehistory, but its slant is toward institutional development rather than particular non-repeatable historical events.According to Harris, the 19th-century anthropologists were theorizing under the presumption that the development of society followed some sort of laws. He decries the loss of that view in the 20th century by the denial that any laws are discernable or that current institutions have any bearing on ancient. He coins the term ideographic for them. The 19th-century views, on the other hand, are nomothetic; that is, they provide laws. He intends "to reassert the methodological priority of the search for the laws of history in the science of man". He is looking for "a general theory of history". His perception of the laws: "I believe that the analogue of the Darwinian strategy in the realm of sociocultural phenomena is the principle of techno-environmental and techno-economic determinism", he calls cultural materialism, which he also details in Cultural Materialism: The Struggle for a Science of Culture.

Elsewhere he refers to "my theories of historical determinism", defining the latter: "By a deterministic relationship among cultural phenomena, I mean merely that similar variables under similar conditions tend to give rise to similar consequences." The use of "tends to" implies some degree of freedom to happen or not happen, but in strict determinism, given certain causes, the result and only that result must occur. Different philosophers, however, use determinism in different senses. The deterministic element that Harris sees is lack of human social engineering: "free will and moral choice have had virtually no significant effect upon the direction taken thus far by evolving systems of social life."

Harris agrees with the 19th-century view that laws are abstractions from empirical evidence: "...sociocultural entities are constructed from the direct or indirect observation of the behavior and thought of specific individuals ...." Institutions are not a physical reality; only people are. When they act in society, they do so according to the laws of history, of which they are not aware; hence, there is no historical element of free will. Like the 20th-century anthropologists in general, Harris places a high value on the empiricism, or collection of data. This function must be performed by trained observers.

He borrows terms from linguistics: just as a phon-etic system is a description of sounds developed without regard to the meaning and structure of the language, while a phon-emic system describes the meaningful sounds actually used within the language, so anthropological data can be emic and etic. Only trained observers can avoid eticism, or description without regard to the meaning in the culture: "... etics are in part observers' emics incorrectly applied to a foreign system...." He makes a further distinction between synchronic and diachronic. Synchronic ("same time") with reference to anthropological data is contemporaneous and cross-cultural. Diachronic ("through time") data shows the development of lines through time. Cultural materialism, being a "processually holistic and globally comparative scientific research strategy" must depend for accuracy on all four types of data. Cultural materialism differs from the others by the insertion of culture as the effect. Different material factors produce different cultures.

Harris, like many other anthropologists, in looking for anthropological method and data before the use of the term anthropology, had little difficulty finding them among the ancient authors. The ancients tended to see players on the stage of history as ethnic groups characterized by the same or similar languages and customs: the Persians, the Germans, the Scythians, etc. Thus the term history meant to a large degree the "story" of the fortunes of these players through time. The ancient authors never formulated laws. Apart from a rudimentary three-age system, the stages of history, such as are found in Lubbock, Tylor, Morgan, Marx and others, are yet unformulated.

Proto-anthropology

Eriksen and Nielsen use the term proto-anthropology to refer to near-anthropological writings, which contain some of the criteria for being anthropology, but not all. They classify proto-anthropology as being "travel writing or social philosophy", going on to assert "It is only when these aspects ... are fused, that is, when data and theory are brought together, that anthropology appears." This process began to occur in the 18th century of the Age of Enlightenment.Classical Age

Many anthropological writers find anthropological-quality theorizing in the works of Classical Greece and Classical Rome; for example, John Myres in Herodotus and Anthropology (1908); E. E. Sikes in The Anthropology of the Greeks (1914); Clyde Kluckhohn in Anthropology and the Classics (1961), and many others. An equally long list may be found in French and German as well as other languages.Herodotus

Herodotus was a 5th-century BC Greek historian who set about to chronicle and explain the Greco-Persian Wars that transpired early in that century. He did so in a surviving work conventionally termed the History or the Histories. His first line begins: "These are the researches of Herodotus of Halicarnassus ...."The Achaemenid Empire, deciding to bring Greece into its domain, conducted a massive invasion across the Bosphorus using multi-cultural troops raised from many different locations. They were decisively defeated by the Greek city-states. Herodotus was far from interested in only the non-repeatable events. He provides ethnic details and histories of the peoples within the empire and to the north of it, in most cases being the first to do so. His methods were reading accounts, interviewing witnesses, and in some cases taking notes for himself.

These "researches" have been considered anthropological since at least as early as the late 19th century. The title, "Father of History" (pater historiae), had been conferred on him probably by Cicero. Pointing out that John Myres in 1908 had believed that Herodotus was an anthropologist on a par with those of his own day, James M. Redfield asserts: "Herodotus, as we know, was both Father of History and Father of Anthropology." Herodotus calls his method of travelling around taking notes "theorizing". Redfield translates it as "tourism" with a scientific intent. He identifies three terms of Herodotus as overlapping on culture: diaitia, material goods such as houses and consumables; ethea, the mores or customs; and nomoi, the authoritative precedents or laws.

Tacitus

The Roman historian, Tacitus, wrote many of our only surviving contemporary accounts of several ancient Celtic and Germanic peoples.Middle Ages

Cannibalism among "the savages" in Brazil, as described and pictured by André Thévet

Table of natural history, 1728 Cyclopaedia

Another candidate for one of the first scholars to carry out comparative ethnographic-type studies in person was the medieval Persian scholar Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī in the eleventh century, who wrote about the peoples, customs, and religions of the Indian subcontinent. According to Akbar S. Ahmed, like modern anthropologists, he engaged in extensive participant observation with a given group of people, learnt their language and studied their primary texts, and presented his findings with objectivity and neutrality using cross-cultural comparisons. Others argue, however, that he hardly can be considered an anthropologist in the conventional sense. He wrote detailed comparative studies on the religions and cultures in the Middle East, Mediterranean, and especially South Asia. Biruni's tradition of comparative cross-cultural study continued in the Muslim world through to Ibn Khaldun's work in the fourteenth century.

Medieval scholars may be considered forerunners of modern anthropology as well, insofar as they conducted or wrote detailed studies of the customs of peoples considered "different" from themselves in terms of geography. John of Plano Carpini reported of his stay among the Mongols. His report was unusual in its detailed depiction of a non-European culture.

Marco Polo's systematic observations of nature, anthropology, and geography are another example of studying human variation across space. Polo's travels took him across such a diverse human landscape and his accounts of the peoples he met as he journeyed were so detailed that they earned for Polo the name "the father of modern anthropology".

Renaissance

The first use of the term "anthropology" in English to refer to a natural science of humanity was apparently in Richard Harvey's 1593 Philadelphus, a defense of the legend of Brutus in British history, which, includes the passage: "Genealogy or issue which they had, Artes which they studied, Actes which they did. This part of History is named Anthropology."The Enlightenment roots of the discipline

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

Many scholars consider modern anthropology as an outgrowth of the Age of Enlightenment (1715–89), a period when Europeans attempted to study human behavior systematically, the known varieties of which had been increasing since the fifteenth century as a result of the first European colonization wave. The traditions of jurisprudence, history, philology, and sociology then evolved into something more closely resembling the modern views of these disciplines and informed the development of the social sciences, of which anthropology was a part.

It took Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) 25 years to write one of the first major treatises on anthropology, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (1798), which treats it as a branch of philosophy. Kant is not generally considered to be a modern anthropologist, as he never left his region of Germany, nor did he study any cultures besides his own. He did, however, begin teaching an annual course in anthropology in 1772. Developments in the systematic study of ancient civilizations through the disciplines of Classics and Egyptology informed both archaeology and eventually social anthropology, as did the study of East and South Asian languages and cultures. At the same time, the Romantic reaction to the Enlightenment produced thinkers, such as Johann Gottfried Herder and later Wilhelm Dilthey, whose work formed the basis for the "culture concept", which is central to the discipline.

Institutionally, anthropology emerged from the development of natural history (expounded by authors such as Buffon) that occurred during the European colonization of the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Programs of ethnographic study originated in this era as the study of the "human primitives" overseen by colonial administrations.

There was a tendency in late eighteenth century Enlightenment thought to understand human society as natural phenomena that behaved according to certain principles and that could be observed empirically. In some ways, studying the language, culture, physiology, and artifacts of European colonies was not unlike studying the flora and fauna of those places.

Early anthropology was divided between proponents of unilinealism, who argued that all societies passed through a single evolutionary process, from the most primitive to the most advanced, and various forms of non-lineal theorists, who tended to subscribe to ideas such as diffusionism. Most nineteenth-century social theorists, including anthropologists, viewed non-European societies as windows onto the pre-industrial human past.

Overview of the modern discipline

Marxist anthropologist Eric Wolf once characterized anthropology as "the most scientific of the humanities, and the most humanistic of the social sciences". Understanding how anthropology developed contributes to understanding how it fits into other academic disciplines. Scholarly traditions of jurisprudence, history, philology and sociology developed during this time and informed the development of the social sciences of which anthropology was a part. At the same time, the Romantic reaction to the Enlightenment produced thinkers such as Herder and later Wilhelm Dilthey whose work formed the basis for the culture concept which is central to the discipline.These intellectual movements in part grappled with one of the greatest paradoxes of modernity: as the world is becoming smaller and more integrated, people's experience of the world is increasingly atomized and dispersed. As Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels observed in the 1840s:

All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed. They are dislodged by new industries, whose introduction becomes a life and death question for all civilized nations, by industries that no longer work up indigenous raw material but raw material drawn from the remotest zones; industries whose products are consumed, not only at home, but in every quarter of the globe. In place of the old wants, satisfied by the production of the country, we find new wants, requiring for their satisfaction the products of distant lands and climes. In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations.Ironically, this universal interdependence, rather than leading to greater human solidarity, has coincided with increasing racial, ethnic, religious, and class divisions, and new—and to some confusing or disturbing—cultural expressions. These are the conditions of life with which people today must contend, but they have their origins in processes that began in the 16th century and accelerated in the 19th century.

Institutionally anthropology emerged from natural history (expounded by authors such as Buffon). This was the study of human beings—typically people living in European colonies. Thus studying the language, culture, physiology, and artifacts of European colonies was more or less equivalent to studying the flora and fauna of those places. It was for this reason, for instance, that Lewis Henry Morgan could write monographs on both The League of the Iroquois and The American Beaver and His Works. This is also why the material culture of 'civilized' nations such as China have historically been displayed in fine arts museums alongside European art while artifacts from Africa or Native North American cultures were displayed in natural history museums with dinosaur bones and nature dioramas. Curatorial practice has changed dramatically in recent years, and it would be wrong to see anthropology as merely an extension of colonial rule and European chauvinism, since its relationship to imperialism was and is complex.

Drawing on the methods of the natural sciences as well as developing new techniques involving not only structured interviews but unstructured "participant-observation"—and drawing on the new theory of evolution through natural selection, they proposed the scientific study of a new object: "humankind", conceived of as a whole. Crucial to this study is the concept "culture", which anthropologists defined both as a universal capacity and propensity for social learning, thinking, and acting (which they see as a product of human evolution and something that distinguishes Homo sapiens—and perhaps all species of genus Homo—from other species), and as a particular adaptation to local conditions that takes the form of highly variable beliefs and practices. Thus, "culture" not only transcends the opposition between nature and nurture; it transcends and absorbs the peculiarly European distinction between politics, religion, kinship, and the economy as autonomous domains. Anthropology thus transcends the divisions between the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities to explore the biological, linguistic, material, and symbolic dimensions of humankind in all forms.

National anthropological traditions

As academic disciplines began to differentiate over the course of the nineteenth century, anthropology grew increasingly distinct from the biological approach of natural history, on the one hand, and from purely historical or literary fields such as Classics, on the other. A common criticism was that many social sciences (such as economists, sociologists, and psychologists) in Western countries focused disproportionately on Western subjects, while anthropology focuseed disproportionately on the "other".Britain

Museums such as the British Museum weren't the only site of anthropological studies: with the New Imperialism period, starting in the 1870s, zoos became unattended "laboratories", especially the so-called "ethnological exhibitions" or "Negro villages". Thus, "savages" from the colonies were displayed, often nudes, in cages, in what has been called "human zoos". For example, in 1906, Congolese pygmy Ota Benga was put by anthropologist Madison Grant in a cage in the Bronx Zoo, labelled "the missing link" between an orangutan and the "white race"—Grant, a renowned eugenicist, was also the author of The Passing of the Great Race (1916). Such exhibitions were attempts to illustrate and prove in the same movement the validity of scientific racism, which first formulation may be found in Arthur de Gobineau's An Essay on the Inequality of Human Races (1853–55). In 1931, the Colonial Exhibition in Paris still displayed Kanaks from New Caledonia in the "indigenous village"; it received 24 million visitors in six months, thus demonstrating the popularity of such "human zoos".Anthropology grew increasingly distinct from natural history and by the end of the nineteenth century the discipline began to crystallize into its modern form—by 1935, for example, it was possible for T.K. Penniman to write a history of the discipline entitled A Hundred Years of Anthropology. At the time, the field was dominated by 'the comparative method'. It was assumed that all societies passed through a single evolutionary process from the most primitive to most advanced. Non-European societies were thus seen as evolutionary 'living fossils' that could be studied in order to understand the European past. Scholars wrote histories of prehistoric migrations which were sometimes valuable but often also fanciful. It was during this time that Europeans first accurately traced Polynesian migrations across the Pacific Ocean for instance—although some of them believed it originated in Egypt. Finally, the concept of race was actively discussed as a way to classify—and rank—human beings based on difference.

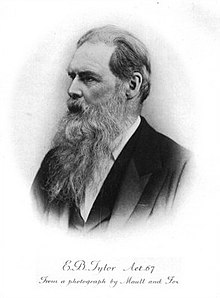

E.B. Tylor and James Frazer

Sir E. B. Tylor (1832-1917), nineteenth-century British anthropologist

Sir James George Frazer (1854-1941)

Edward Burnett Tylor (2 October 1832 – 2 January 1917) and James George Frazer (1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) are generally considered the antecedents to modern social anthropology in Britain. Although Tylor undertook a field trip to Mexico, both he and Frazer derived most of the material for their comparative studies through extensive reading, not fieldwork, mainly the Classics (literature and history of Greece and Rome), the work of the early European folklorists, and reports from missionaries, travelers, and contemporaneous ethnologists.

Tylor advocated strongly for unilinealism and a form of "uniformity of mankind". Tylor in particular laid the groundwork for theories of cultural diffusionism, stating that there are three ways that different groups can have similar cultural forms or technologies: "independent invention, inheritance from ancestors in a distant region, transmission from one race to another".

Tylor formulated one of the early and influential anthropological conceptions of culture as "that complex whole, which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by [humans] as [members] of society". However, as Stocking notes, Tylor mainly concerned himself with describing and mapping the distribution of particular elements of culture, rather than with the larger function, and he generally seemed to assume a Victorian idea of progress rather than the idea of non-directional, multilineal cultural development proposed by later anthropologists.

Tylor also theorized about the origins of religious beliefs in human beings, proposing a theory of animism as the earliest stage, and noting that "religion" has many components, of which he believed the most important to be belief in supernatural beings (as opposed to moral systems, cosmology, etc.). Frazer, a Scottish scholar with a broad knowledge of Classics, also concerned himself with religion, myth, and magic. His comparative studies, most influentially in the numerous editions of The Golden Bough, analyzed similarities in religious belief and symbolism globally. Neither Tylor nor Frazer, however, was particularly interested in fieldwork, nor were they interested in examining how the cultural elements and institutions fit together. The Golden Bough was abridged drastically in subsequent editions after his first.

Bronislaw Malinowski and the British School

Toward the turn of the twentieth century, a number of anthropologists became dissatisfied with this categorization of cultural elements; historical reconstructions also came to seem increasingly speculative to them. Under the influence of several younger scholars, a new approach came to predominate among British anthropologists, concerned with analyzing how societies held together in the present (synchronic analysis, rather than diachronic or historical analysis), and emphasizing long-term (one to several years) immersion fieldwork. Cambridge University financed a multidisciplinary expedition to the Torres Strait Islands in 1898, organized by Alfred Cort Haddon and including a physician-anthropologist, William Rivers, as well as a linguist, a botanist, and other specialists. The findings of the expedition set new standards for ethnographic description.A decade and a half later, Polish anthropology student Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942) was beginning what he expected to be a brief period of fieldwork in the old model, collecting lists of cultural items, when the outbreak of the First World War stranded him in New Guinea. As a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire resident on a British colonial possession, he was effectively confined to New Guinea for several years.

He made use of the time by undertaking far more intensive fieldwork than had been done by British anthropologists, and his classic ethnography, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922) advocated an approach to fieldwork that became standard in the field: getting "the native's point of view" through participant observation. Theoretically, he advocated a functionalist interpretation, which examined how social institutions functioned to satisfy individual needs.

British social anthropology had an expansive moment in the Interwar period, with key contributions coming from the Polish-British Bronisław Malinowski and Meyer Fortes.

A. R. Radcliffe-Brown also published a seminal work in 1922. He had carried out his initial fieldwork in the Andaman Islands in the old style of historical reconstruction. However, after reading the work of French sociologists Émile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, Radcliffe-Brown published an account of his research (entitled simply The Andaman Islanders) that paid close attention to the meaning and purpose of rituals and myths. Over time, he developed an approach known as structural functionalism, which focused on how institutions in societies worked to balance out or create an equilibrium in the social system to keep it functioning harmoniously. (This contrasted with Malinowski's functionalism, and was quite different from the later French structuralism, which examined the conceptual structures in language and symbolism.)

Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown's influence stemmed from the fact that they, like Boas, actively trained students and aggressively built up institutions that furthered their programmatic ambitions. This was particularly the case with Radcliffe-Brown, who spread his agenda for "Social Anthropology" by teaching at universities across the British Commonwealth. From the late 1930s until the postwar period appeared a string of monographs and edited volumes that cemented the paradigm of British Social Anthropology (BSA). Famous ethnographies include The Nuer, by Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard, and The Dynamics of Clanship Among the Tallensi, by Meyer Fortes; well-known edited volumes include African Systems of Kinship and Marriage and African Political Systems.

Post WW II trends

Max Gluckman, together with many of his colleagues at the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute and students at Manchester University, collectively known as the Manchester School, took BSA in new directions through their introduction of explicitly Marxist-informed theory, their emphasis on conflicts and conflict resolution, and their attention to the ways in which individuals negotiate and make use of the social structural possibilities.In Britain, anthropology had a great intellectual impact, it "contributed to the erosion of Christianity, the growth of cultural relativism, an awareness of the survival of the primitive in modern life, and the replacement of diachronic modes of analysis with synchronic, all of which are central to modern culture."

Later in the 1960s and 1970s, Edmund Leach and his students Mary Douglas and Nur Yalman, among others, introduced French structuralism in the style of Lévi-Strauss; while British anthropology has continued to emphasize social organization and economics over purely symbolic or literary topics, differences among British, French, and American sociocultural anthropologies have diminished with increasing dialogue and borrowing of both theory and methods. Today, social anthropology in Britain engages internationally with many other social theories and has branched in many directions.

In countries of the British Commonwealth, social anthropology has often been institutionally separate from physical anthropology and primatology, which may be connected with departments of biology or zoology; and from archaeology, which may be connected with departments of Classics, Egyptology, and the like. In other countries (and in some, particularly smaller, British and North American universities), anthropologists have also found themselves institutionally linked with scholars of folklore, museum studies, human geography, sociology, social relations, ethnic studies, cultural studies, and social work.

Anthropology has been used in Britain to provide an alternative explanation for the Financial crisis of 2007–2010 to the technical explanations rooted in economic and political theory. Dr. Gillian Tett, a Cambridge University trained anthropologist who went on to become a senior editor at the Financial Times is one of the leaders in this use of anthropology.

Canada

Canadian anthropology began, as in other parts of the Colonial world, as ethnological data in the records of travellers and missionaries. In Canada, Jesuit missionaries such as Fathers LeClercq, Le Jeune and Sagard, in the 17th century, provide the oldest ethnographic records of native tribes in what was then the Dominion of Canada. The academic discipline has drawn strongly on both the British Social Anthropology and the American Cultural Anthropology traditions, producing a hybrid "Socio-cultural" anthropology.George Mercer Dawson

True anthropology began with a Government department: the Geological Survey of Canada, and George Mercer Dawson (director in 1895). Dawson's support for anthropology created impetus for the profession in Canada. This was expanded upon by Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, who established a Division of Anthropology within the Geological Survey in 1910.Edward Sapir

Anthropologists were recruited from England and the USA, setting the foundation for the unique Canadian style of anthropology. Scholars include the linguist and Boasian Edward Sapir.France

Anthropology in France has a less clear genealogy than the British and American traditions, in part because many French writers influential in anthropology have been trained or held faculty positions in sociology, philosophy, or other fields rather than in anthropology.

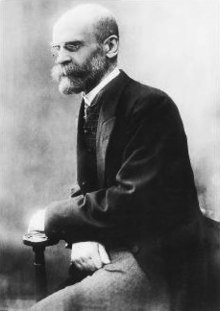

Marcel Mauss

Most commentators consider Marcel Mauss (1872–1950), nephew of the influential sociologist Émile Durkheim, to be the founder of the French anthropological tradition. Mauss belonged to Durkheim's Année Sociologique group. While Durkheim and others examined the state of modern societies, Mauss and his collaborators (such as Henri Hubert and Robert Hertz) drew on ethnography and philology to analyze societies that were not as 'differentiated' as European nation states.Two works by Mauss in particular proved to have enduring relevance: Essay on the Gift, a seminal analysis of exchange and reciprocity, and his Huxley lecture on the notion of the person, the first comparative study of notions of person and selfhood cross-culturally.

Throughout the interwar years, French interest in anthropology often dovetailed with wider cultural movements such as surrealism and primitivism, which drew on ethnography for inspiration. Marcel Griaule and Michel Leiris are examples of people who combined anthropology with the French avant-garde. During this time most of what is known as ethnologie was restricted to museums, such as the Musée de l'Homme founded by Paul Rivet, and anthropology had a close relationship with studies of folklore.

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Above all, Claude Lévi-Strauss helped institutionalize anthropology in France. Along with the enormous influence that his theory of structuralism exerted across multiple disciplines, Lévi-Strauss established ties with American and British anthropologists. At the same time, he established centers and laboratories within France to provide an institutional context within anthropology, while training influential students such as Maurice Godelier and Françoise Héritier. They proved influential in the world of French anthropology. Much of the distinct character of France's anthropology today is a result of the fact that most anthropology is carried out in nationally funded research laboratories (CNRS) rather than academic departments in universities.Other influential writers in the 1970s include Pierre Clastres, who explains in his books on the Guayaki tribe in Paraguay that "primitive societies" actively oppose the institution of the state. These stateless societies are not less evolved than societies with states, but chose to conjure the institution of authority as a separate function from society. The leader is only a spokesperson for the group when it has to deal with other groups ("international relations") but has no inside authority, and may be violently removed if he attempts to abuse this position.

The most important French social theorist since Foucault and Lévi-Strauss is Pierre Bourdieu, who trained formally in philosophy and sociology and eventually held the Chair of Sociology at the Collège de France. Like Mauss and others before him, he worked on topics both in sociology and anthropology. His fieldwork among the Kabyle of Algeria places him solidly in anthropology, while his analysis of the function and reproduction of fashion and cultural capital in European societies places him as solidly in sociology.

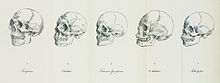

Blumenbach's five races.

United States

From its beginnings in the early 19th century through the early 20th century, anthropology in the United States was influenced by the presence of Native American societies.

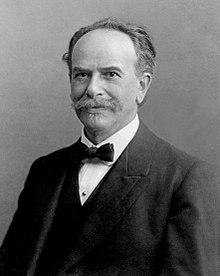

Franz Boas, one of the pioneers of modern anthropology, often called the "Father of American Anthropology"

Cultural anthropology in the United States was influenced greatly by the ready availability of Native American societies as ethnographic subjects. The field was pioneered by staff of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of American Ethnology, men such as John Wesley Powell and Frank Hamilton Cushing.

Late-eighteenth-century ethnology established the scientific foundation for the field, which began to mature in the United States during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). Jackson was responsible for implementing the Indian Removal Act, the coerced and forced removal of an estimated 100,000 American Indians during the 1830s to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma; for insuring that the franchise was extended to all white men, irrespective of financial means while denying virtually all black men the right to vote; and, for suppressing abolitionists' efforts to end slavery while vigorously defending that institution. Finally, he was responsible for appointing Chief Justice Roger B. Taney who would decide, in Scott v. Sandford (1857), that Negroes were "beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race ... and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect". As a result of this decision, black people, whether free or enslaved, could never become citizens of the United States.

It was in this context that the so-called American School of Anthropology thrived as the champion of polygenism or the doctrine of multiple origins—sparking a debate between those influenced by the Bible who believed in the unity of humanity and those who argued from a scientific standpoint for the plurality of origins and the antiquity of distinct types. Like the monogenists, these theories were not monolithic and often used words like races, species, hybrid, and mongrel interchangeably. A scientific consensus began to emerge during this period "that there exists a Genus Homo, embracing many primordial types of 'species'". Charles Caldwell, Samuel George Morton, Samuel A. Cartwright, George Gliddon, Josiah C. Nott, and Louis Agassiz, and even South Carolina Governor James Henry Hammond were all influential proponents of this school. While some were disinterested scientists, others were passionate advocates who used science to promote slavery in a period of increasing sectional strife. All were complicit in establishing the putative science that justified slavery, informed the Dred Scott decision, underpinned miscegenation laws, and eventually fueled Jim Crow. Samuel G. Morton, for example, claimed to be just a scientist but he did not hesitate to provide evidence of Negro inferiority to John C. Calhoun, the prominent pro-slavery Secretary of State to help him negotiate the annexation of Texas as a slave state.

The high-water mark of polygenic theories was Josiah Nott and Gliddon's voluminous eight-hundred page tome titled Types of Mankind, published in 1854. Reproducing the work of Louis Agassiz and Samuel Morton, the authors spread the virulent and explicitly racist views to a wider, more popular audience. The first printing sold out quickly and by the end of the century it had undergone nine editions. Although many Southerners felt that all the justification for slavery they needed was found in the Bible, others used the new science to defend slavery and the repression of American Indians. Abolitionists, however, felt they had to take this science on its own terms. And for the first time, African American intellectuals waded into the contentious debate. In the immediate wake of Types of Mankind and during the pitched political battles that led to Civil War, Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), the statesman and persuasive abolitionist, directly attacked the leading theorists of the American School of Anthropology. In an 1854 address, entitled "The Claims of the Negro Ethnologically Considered", Douglass argued that "by making the enslaved a character fit only for slavery, [slaveowners] excuse themselves for refusing to make the slave a freeman.... For let it be once granted that the human race are of multitudinous origin, naturally different in their moral, physical, and intellectual capacities ... a chance is left for slavery, as a necessary institution.... There is no doubt that Messrs. Nott, Glidden, Morton, Smith and Agassiz were duly consulted by our slavery propagating statesmen" (p. 287).

Lewis Henry Morgan in the United States

Lewis Henry Morgan (1818–1881), a lawyer from Rochester, New York, became an advocate for and ethnological scholar of the Iroquois. His comparative analyses of religion, government, material culture, and especially kinship patterns proved to be influential contributions to the field of anthropology. Like other scholars of his day (such as Edward Tylor), Morgan argued that human societies could be classified into categories of cultural evolution on a scale of progression that ranged from savagery, to barbarism, to civilization. He focused on understanding how cultures integrated and systematized, and how the various features of one culture indicate an evolutionary status in comparison with other cultures. Generally, Morgan used technology (such as bowmaking or pottery) as an indicator of position on this scale.Franz Boas

Franz Boas established academic anthropology in the United States in opposition to this sort of evolutionary perspective. His approach was empirical, skeptical of overgeneralizations, and eschewed attempts to establish universal laws. For example, Boas studied immigrant children to demonstrate that biological race was not immutable, and that human conduct and behavior resulted from nurture, rather than nature.Influenced by the German tradition, Boas argued that the world was full of distinct cultures, rather than societies whose evolution could be measured by how much or how little "civilization" they had. He believed that each culture has to be studied in its particularity, and argued that cross-cultural generalizations, like those made in the natural sciences, were not possible.

In doing so, he fought discrimination against immigrants, blacks, and indigenous peoples of the Americas. Many American anthropologists adopted his agenda for social reform, and theories of race continue to be popular subjects for anthropologists today. The so-called "Four Field Approach" has its origins in Boasian Anthropology, dividing the discipline in the four crucial and interrelated fields of sociocultural, biological, linguistic, and archaic anthropology (e.g. archaeology). Anthropology in the United States continues to be deeply influenced by the Boasian tradition, especially its emphasis on culture.

Ruth Benedict in 1937

Boas used his positions at Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History to train and develop multiple generations of students. His first generation of students included Alfred Kroeber, Robert Lowie, Edward Sapir and Ruth Benedict, who each produced richly detailed studies of indigenous North American cultures. They provided a wealth of details used to attack the theory of a single evolutionary process. Kroeber and Sapir's focus on Native American languages helped establish linguistics as a truly general science and free it from its historical focus on Indo-European languages.

The publication of Alfred Kroeber's textbook, Anthropology, marked a turning point in American anthropology. After three decades of amassing material, Boasians felt a growing urge to generalize. This was most obvious in the 'Culture and Personality' studies carried out by younger Boasians such as Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. Influenced by psychoanalytic psychologists including Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, these authors sought to understand the way that individual personalities were shaped by the wider cultural and social forces in which they grew up.

Though such works as Coming of Age in Samoa and The Chrysanthemum and the Sword remain popular with the American public, Mead and Benedict never had the impact on the discipline of anthropology that some expected. Boas had planned for Ruth Benedict to succeed him as chair of Columbia's anthropology department, but she was sidelined by Ralph Linton, and Mead was limited to her offices at the AMNH.

Other countries

Anthropology as it emerged amongst the Western colonial powers (mentioned above) has generally taken a different path than that in the countries of southern and central Europe (Italy, Greece, and the successors to the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires). In the former, the encounter with multiple, distinct cultures, often very different in organization and language from those of Europe, has led to a continuing emphasis on cross-cultural comparison and a receptiveness to certain kinds of cultural relativism.In the successor states of continental Europe, on the other hand, anthropologists often joined with folklorists and linguists in building cultural perspectives on nationalism. Ethnologists in these countries tended to focus on differentiating among local ethnolinguistic groups, documenting local folk culture, and representing the prehistory of what has become a nation through various forms of public education (e.g., museums of several kinds).

In this scheme, Russia occupied a middle position. On the one hand, it had a large region (largely east of the Urals) of highly distinct, pre-industrial, often non-literate peoples, similar to the situation in the Americas. On the other hand, Russia also participated to some degree in the nationalist (cultural and political) movements of Central and Eastern Europe. After the Revolution of 1917, views expressed by anthropologists in the USSR, and later the Soviet Bloc countries, were highly shaped by the requirement to conform to Marxist theories of social evolution.

In Greece, there was since the 19th century a science of the folklore called laographia (laography), in the form of "a science of the interior", although theoretically weak; but the connotation of the field deeply changed after World War II, when a wave of Anglo-American anthropologists introduced a science "of the outside".

In Italy, the development of ethnology and related studies did not receive as much attention as other branches of learning, but nonetheless included important researchers and thinkers like Ernesto De Martino.

Germany and Norway are the countries that showed the most division and conflict between scholars focusing on domestic socio-cultural issues and scholars focusing on "other" societies.. Some German and Austrian scholars have increased cultural anthropology as both legal anthropology regarding "other" societies and anthropology of Western civilization.

The development of world anthropologies has followed different trajectories.