Criticism of multiculturalism questions the ideal of the maintenance of distinct ethnic cultures within a country. Multiculturalism is a particular subject of debate in certain European nations that are associated with the idea of a single nation within their country. Critics of multiculturalism may argue against cultural integration of different ethnic and cultural groups to the existing laws and values of the country. Alternatively critics may argue for assimilation of different ethnic and cultural groups to a single national identity.

Australia

The response to multiculturalism in Australia has been varied. A nationalist, anti-mass immigration party, the One Nation Party, was formed by Pauline Hanson in the late 1990s. The party enjoyed brief electoral success, most notably in its home state of Queensland, but became electorally marginalized until its resurgence in 2016. In the late 1990s, One Nation called for the abolition of multiculturalism alleging that it represented "a threat to the very basis of the Australian culture, identity and shared values", arguing that there was "no reason why migrant cultures should be maintained at the expense of our shared, national culture."

An Australian Federal Government proposal in 2006 to introduce a compulsory citizenship test, which would assess English skills and knowledge of Australian values, sparked renewed debate over the future of multiculturalism in Australia. Andrew Robb, then Parliamentary Secretary for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, told a conference in November 2006 that some Australians worried the term "multicultural" had been transformed by interest groups into a philosophy that put "allegiances to original culture ahead of national loyalty, a philosophy which fosters separate development, a federation of ethnic cultures, not one community". He added: "A community of separate cultures fosters a rights mentality, rather than a responsibilities mentality. It is divisive. It works against quick and effective integration." However, criticism of multiculturalism in Australia has also emerged in the context of a construction of a binary "us" vs. "them" discourse. Such discourse was employed in the 2001 election by the Coalition (a formal alliance between the Liberal Party of Australia and the National Party of Australia) as it expressed its views on immigration: "We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come." This discourse was mired in anti-elitism and populism, as John Howard sought to appeal to the "fears, resentments and insecurities" of "ordinary Australians." The discourse further included a backlash against "boat people," particularly refugees from Malaysia, who were accused of trying to "exploit our compassion and generosity." The Australian citizenship test commenced in October 2007 for all new citizens between the ages of 18 and 60.

In January 2007 the Howard Government removed the word "multicultural" from the name of the Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, changing its name to the Department of Immigration and Citizenship.

Intellectual critique

The earliest academic critics of multiculturalism in Australia were the philosophers Lachlan Chipman and Frank Knopfelmacher, sociologist Tanya Birrell and the political scientist Raymond Sestito. Chipman and Knopfelmacher were concerned with threats to social cohesion, while Birrell's concern was that multiculturalism obscures the social costs associated with large scale immigration that fall most heavily on the most recently arrived and unskilled immigrants. Sestito's arguments were based on the role of political parties. He argued that political parties were instrumental in pursuing multicultural policies, and that these policies would put strain on the political system and would not promote better understanding in the Australian community.It was the high-profile historian Geoffrey Blainey, however, who first achieved mainstream recognition for the anti-multiculturalist cause when he wrote that multiculturalism threatened to transform Australia into a "cluster of tribes". In his 1984 book All for Australia, Blainey criticised multiculturalism for tending to "emphasise the rights of ethnic minorities at the expense of the majority of Australians" and also for tending to be "anti-British", even though "people from the United Kingdom and Ireland form the dominant class of pre-war immigrants and the largest single group of post-war immigrants."

According to Blainey, such a policy, with its "emphasis on what is different and on the rights of the new minority rather than the old majority," was unnecessarily creating division and threatened national cohesion. He argued that "the evidence is clear that many multicultural societies have failed and that the human cost of the failure has been high" and warned that "we should think very carefully about the perils of converting Australia into a giant multicultural laboratory for the assumed benefit of the peoples of the world."

In one of his numerous criticisms of multiculturalism, Blainey wrote:

For the millions of Australians who have no other nation to fall back upon, multiculturalism is almost an insult. It is divisive. It threatens social cohesion. It could, in the long-term, also endanger Australia's military security because it sets up enclaves which in a crisis could appeal to their own homelands for help.Blainey remained a persistent critic of multiculturalism into the 1990s, denouncing multiculturalism as "morally, intellectually and economically ... a sham".

The late historian John Hirst was another intellectual critic of multiculturalism. He has argued that while multiculturalism might serve the needs of ethnic politics and the demands of certain ethnic groups for government funding for the promotion of their separate ethnic identity, it was a perilous concept on which to base national policy.

Critics associated with the Centre for Population and Urban Research at Monash University have argued that both Right and Left factions in the Australian Labor Party have adopted a multicultural stance for the purposes of increasing their support within the party. A manifestation of this embrace of multiculturalism has been the creation of ethnic branches within the Labor Party and ethnic branch stacking.

Following the upsurge of support for the One Nation Party in 1996, Lebanese-born Australian anthropologist Ghassan Hage published a critique in 1997 of Australian multiculturalism in the book White Nation.

Australian political ethologist Frank Salter, author of On Genetic Interests: Family, Ethnicity, and Humanity in an Age of Mass Migration, has argued that multiculturalism forms "part of an ideological-administrative system that is helping swamp the Australian nation through ethnically diverse immigration." This, in turn, is "putting at risk the nation's ability to produce the public goods that nations excel in producing: relative cohesion and harmony, public altruism, trust, efficient government and political stability."

Salter has written:

Diversity is not the only deleterious side effect of multiculturalism. Another is to perpetuate population growth because immigration is part of the quid pro quo offered ethnic minorities in exchange for votes. Perpetual large scale immigration cannot be sustained for well-rehearsed environmental reasons. In the end failure to regulate population growth causes severe suffering and social and economic dislocation. It follows that multiculturalism should be counteracted as part of a responsible population policy. The conflict between the two policies is already evident. The charge of racism is often directed at recommendations for reducing immigration overall, even without changing the ethnic mix.In Salter's view, the current model of multiculturalism is flawed as it tends to be "asymmetrical" and exclude Australia's historic Anglo-Celtic majority as a legitimate interest group.

In contrast to the multicultural doctrine which promotes ethnic diversity, Salter has expounded the case for limiting diversity within the nation-state, asserting that "multi-ethnic societies are often confronted with the problem of discrimination and group conflict." . According to Salter:

Cross-cultural comparisons reveal the wisdom of Australia's first prime minister Edmund Barton who believed that ethnic homogeneity must be the cornerstone of Australian nation-building. More ethnically homogeneous nations are better able to build public goods, are more democratic, less corrupt, have higher productivity and less inequality, are more trusting and care more for the disadvantaged, develop social and economic capital faster, have lower crime rates, are more resistant to external shocks, and are better global citizens, for example by giving more foreign aid. Moreover, they are less prone to civil war, the greatest source of violent death in the twentieth century.

Canada

Toronto's Chinatown is an ethnic enclave located in the city centre

Many Québécois, despite an official national bilingualism policy, insist that multiculturalism threatens to reduce them to just another ethnic group. Quebec's policy seeks to promote interculturalism, welcoming people of all origins while insisting that they integrate into Quebec's majority French-speaking society. In 2008, a Consultation Commission on Accommodation Practices Related to Cultural Differences, headed by sociologist Gerard Bouchard and philosopher Charles Taylor, recognized that Quebec is a de facto pluralist society, but that the Canadian multiculturalism model "does not appear well suited to conditions in Quebec".

According to a study conducted by The University of Victoria, many Canadians do not feel a strong sense of belonging in Canada, or cannot integrate themselves into society as a result of ethnic enclaves. Many immigrants to Canada choose to live in ethnic enclaves because it can be much easier than fitting in with mainstream Canadian culture.

Foreign born Canadian, Neil Bissoondath in his book Selling Illusions: The Cult of Multiculturalism in Canada, argues that official multiculturalism limits the freedom of minority members, by confining them to cultural and geographic ethnic enclaves. He also argues that cultures are very complex, and must be transmitted through close family and kin relations. To him, the government view of cultures as being about festivals and cuisine is a crude oversimplification that leads to easy stereotyping.

Canadian Daniel Stoffman's book Who Gets In questions the policy of Canadian multiculturalism. Stoffman points out that many cultural practices, such as allowing dog meat to be served in restaurants and street cockfighting, are simply incompatible with Canadian and Western culture. He also raises concern about the number of recent immigrants who are not being linguistically integrated into Canada (i.e., not learning either English or French). He stresses that multiculturalism works better in theory than in practice and Canadians need to be far more assertive about valuing the "national identity of English-speaking Canada".

Canadian Joseph Garcea explores the validity of attacks on multiculturalism because it supposedly segregates the peoples of Canada; multiculturalism hurts the Canadian, Québécois, and Aboriginal culture, identity, and nationalism projects; and, it perpetuates conflicts between and within groups. Oxford sociologist, Reza Hasmath, argues that the multicultural project in Canada has the potential to hinder substantive equality in the labour market for ethnic minorities.

Germany

Criticisms of parallel societies established by some immigrant communities increasingly came to the fore in the German public discourse during the 1990s, giving rise to the concept of the Leitkultur ("lead culture"). In October 2010, amid a nationwide controversy about Thilo Sarrazin's bestselling book Deutschland schafft sich ab ("Germany is abolishing Itself"), chancellor Angela Merkel of the conservative Christian Democratic Union judged attempts to build a multicultural society in Germany to have "failed, utterly failed". She added: "The concept that we are now living side by side and are happy about it does not work". She continued to say that immigrants should integrate and adopt Germany's culture and values. This has added to a growing debate within Germany on the levels of immigration, its effect on the country and the degree to which Muslim immigrants have integrated into German society. According to one poll around the time, one-third of Germans believed the country was "overrun by foreigners".Italy

Italy has recently seen a substantial rise in immigration and an influx of African immigrants.Many intellectuals have opposed multiculturalism among those:

Ida Magli, professor emeritus of cultural anthropology at the University of Rome. She was a contributor to the weekly L'Espresso and was a columnist for the daily La Repubblica. She expressed criticism of multicultural societies.

Oriana Fallaci was an Italian journalist, author, and political interviewer. A partisan during World War II, she had a long and successful journalistic career. Fallaci became famous worldwide for her coverage of war and revolution, and her interviews with many world leaders during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. After retirement, she returned to the spotlight after writing a series of controversial articles and books critical of Islam and immigration.

Japan

Japanese society, with its ideology of homogeneity, has traditionally rejected any need to recognize ethnic differences in Japan, even as such claims have been rejected by such ethnic minorities as the Ainu and Ryukyuans. Former Japanese Prime Minister (Deputy Prime Minister as of 26 December 2012) Taro Aso has called Japan a "one race" nation.Malaysia

Malaysia is a multicultural society with a Muslim Malay majority and substantial Malaysian Chinese and Malaysian Indian minorities. Criticisms of multiculturalism have been periodically sparked by the entrenched constitutional position the Malay ethnicity enjoys through, inter alia, the Malaysian social contract. Contrary to other countries, in Malaysia affirmative action are often tailored to the needs of the Malay majority population. In 2006, the forced removal of Hindu temples across the country has led to accusations of "an unofficial policy of Hindu temple-cleansing in Malaysia".Netherlands

Legal philosopher Paul Cliteur attacked multiculturalism in his book The Philosophy of Human Rights. Cliteur rejects all political correctness on the issue: Western culture, the Rechtsstaat (rule of law), and human rights are superior to non-Western culture and values. They are the product of the Enlightenment. Cliteur sees non-Western cultures not as merely different but as anachronistic. He sees multiculturalism primarily as an unacceptable ideology of cultural relativism, which would lead to acceptance of barbaric practices, including those brought to the Western World by immigrants. Cliteur lists infanticide, torture, slavery, oppression of women, homophobia, racism, anti-Semitism, gangs, female genital cutting, discrimination by immigrants, suttee, and the death penalty. Cliteur compares multiculturalism to the moral acceptance of Auschwitz, Joseph Stalin, Pol Pot and the Ku Klux Klan.In 2000, Paul Scheffer—a member of the Labour Party and subsequently a professor of urban studies—published his essay "The multicultural tragedy", an essay critical of both immigration and multiculturalism. Scheffer is a committed supporter of the nation-state, assuming that homogeneity and integration are necessary for a society: the presence of immigrants undermines this. A society does have a finite "absorptive capacity" for those from other cultures, he says, but this has been exceeded in the Netherlands. He specifically cites failure to assimilate, spontaneous ethnic segregation, adaptation problems such as school drop-out, unemployment, and high crime rates, and opposition to secularism among Muslim immigrants as the main problems resulting from immigration.

United Kingdom

With considerable immigration after the Second World War making the UK an increasingly ethnically and racially diverse state, race relations policies have been developed that broadly reflect the principles of multiculturalism, although there is no official national commitment to the concept. This model has faced criticism on the grounds that it has failed to sufficiently promote social integration, although some commentators have questioned the dichotomy between diversity and integration that this critique presumes. It has been argued that the UK government has since 2001, moved away from policy characterised by multiculturalism and towards the assimilation of minority communities.Opposition has grown to state sponsored multicultural policies, with some believing that it has been a costly failure. Critics of the policy come from many parts of British society. There is now a debate in the UK over whether explicit multiculturalism and "social cohesion and inclusion" are in fact mutually exclusive. In the wake of the 7 July 2005 London bombings David Davis, the opposition Conservative shadow home secretary, called on the government to scrap its "outdated" policy of multiculturalism.

The British columnist Leo McKinstry has persistently criticized multiculturalism, stating that "Britain is now governed by a suicide cult bent on wiping out any last vestige of nationhood" and called multiculturalism a "profoundly disturbing social experiment".

McKinstry also wrote:

We are paying a terrible price for the creed of Left-wing politicians. They pose as champions of progress yet their fixation with multiculturalism is dragging us into a new dark age. In many of our cities, social solidarity is being replaced by divisive tribalism, democracy by identity politics. Real integration is impossible when ethnic groups are encouraged to cling to customs, practices, even languages from their homeland.Trevor Phillips, the head of the Commission for Racial Equality, who has called for an official end to multicultural policy, has criticised "politically correct liberals for their "misguided" pandering to the ethnic lobby".

Journalist Ed West argued in his 2013 book, The Diversity Illusion, that the British political establishment had uncritically embraced multiculturalism without proper consideration of the downsides of ethnic diversity. He wrote:

Everyone in a position of power held the same opinion. Diversity was a good in itself, so making Britain truly diverse would enrich it and bring 'significant cultural contributions', reflecting a widespread belief among the ruling classes that multiculturalism and cultural, racial and religious diversity were morally positive things whatever the consequences. This is the unthinking assumption held by almost the entire political, media and education establishment. It is the diversity illusion.West has also argued:

Advocates of multiculturalism argue that immigrants prefer to stick together because of racism and the fear of racial violence, as well as the bonds of community. This is perfectly reasonable, but if this is the case, why not the same for natives too? If multiculturalism is right because minorities feel better among themselves, why have mass immigration at all, since it must obviously make everyone miserable? (And if diversity 'enriches' and strengthens, why integrate, since that will only reduce diversity?) All the arguments for multiculturalism—that people feel safer, more comfortable among people of the same group, and that they need their own cultural identity—are arguments against immigration, since English people must also feel the same. If people categorised as "white Britons" are not afforded that indulgence because they are a majority, do they attain it when they become a minority?In the May 2004 edition of Prospect Magazine, the editor David Goodhart temporarily couched the debate on multiculturalism in terms of whether a modern welfare state and a "good society" is sustainable as its citizens become increasingly diverse.

In November 2005 John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York, stated, "Multiculturalism has seemed to imply, wrongly for me: let other cultures be allowed to express themselves but do not let the majority culture at all tell us its glories, its struggles, its joys, its pains." The Bishop of Rochester Michael Nazir-Ali was also critical, calling for the Church to regain a prominent position in public life and blaming the "newfangled and insecurely founded doctrine of multiculturalism" for entrenching the segregation of communities.

Whilst minority cultures are allowed to remain distinct, British culture and traditions are sometimes perceived as exclusive and adapted accordingly, often without the consent of the local population. For instance, Birmingham City Council was heavily criticised when it was alleged to have renamed Christmas as "Winterval" in 1998, although in truth it had done no such thing.

In August 2006, the community and local government secretary Ruth Kelly made a speech perceived as signalling the end of multiculturalism as official policy. In November 2006, Prime Minister Tony Blair stated that Britain has certain "essential values" and that these are a "duty". He did not reject multiculturalism outright, but he included British heritage among the essential values:

When it comes to our essential values—belief in democracy, the rule of law, tolerance, equal treatment for all, respect for this country and its shared heritage—then that is where we come together, it is what we hold in common.

New Labour and multiculturalism

Renewed controversy on the subject came to the fore when Andrew Neather—a former adviser to Jack Straw, Tony Blair and David Blunkett—said that Labour ministers had a hidden agenda in allowing mass immigration into Britain, to "change the face of Britain forever". This alleged conspiracy has become known by the sobriquet "Neathergate".According to Neather, who was present at closed meetings in 2000, a secret Government report called for mass immigration to change Britain's cultural make-up, and that "mass immigration was the way that the government was going to make the UK truly multicultural". Neather went on to say that "the policy was intended—even if this wasn't its main purpose — to rub the right's nose in diversity and render their arguments out of date".

This was later affirmed after a request through the freedom of information act secured access to the full version of a 2000 government report on immigration that had been heavily edited on a previous release. The Conservative party demanded an independent inquiry into the issue and alleged that the document showed that Labour had overseen a deliberate open-door policy on immigration to boost multiculturalism for political ends.

In February 2011, the then Prime Minister David Cameron stated that the "doctrine of state multiculturalism" (promoted by the previous Labour government) had failed and will no longer be state policy. He stated that the UK needed a stronger national identity and signalled a tougher stance on groups promoting Islamist extremism. However, official statistics showed that EU and non-EU mass immigration, together with asylum seeker applications, all increased substantially during Cameron's term in office.

United States

The U.S. Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act in 1921, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924. The Immigration Act of 1924 was aimed at further restricting the Southern and Eastern Europeans, especially Italians and Slavs, who had begun to enter the country in large numbers beginning in the 1890s. Most of the European refugees fleeing the Nazis and World War II were barred from coming to the United States.In the 1980s and 1990s many criticisms were expressed, from both the left and right. Criticisms come from a wide variety of perspectives, but predominantly from the perspective of liberal individualism, from American conservatives concerned about shared traditional values, and from a national unity perspective.

A prominent criticism in the US, later echoed in Europe, Canada and Australia, was that multiculturalism undermined national unity, hindered social integration and cultural assimilation, and led to the fragmentation of society into several ethnic factions (Balkanization).

In 1991, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., a former advisor to the Kennedy and other US administrations and Pulitzer Prize winner, published a book critical of multiculturalism with the title The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society.

In his 1991 work, Illiberal Education, Dinesh D'Souza argues that the entrenchment of multiculturalism in American universities undermined the universalist values that liberal education once attempted to foster. In particular, he was disturbed by the growth of ethnic studies programs (e.g., black studies).

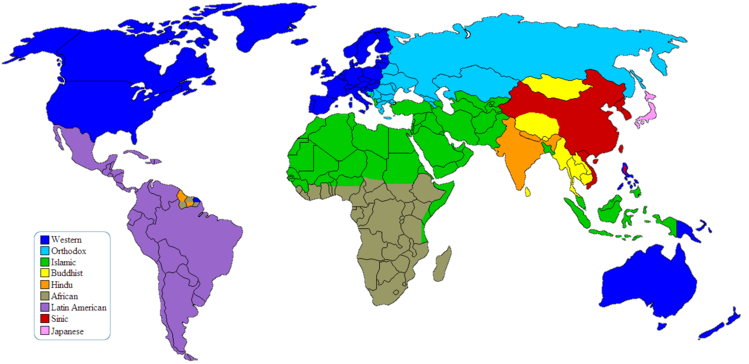

The late Samuel P. Huntington, political scientist and author, known for his Clash of Civilizations theory, described multiculturalism as "basically an anti-Western ideology." According to Huntington, multiculturalism had "attacked the identification of the United States with Western civilization, denied the existence of a common American culture, and promoted racial, ethnic, and other subnational cultural identities and groupings." Huntington outlined the risks he associated with multiculturalism in his 2004 book Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity.

Criticism of multiculturalism in the US was not always synonymous with opposition to immigration. Some politicians did address both themes, notably Patrick Buchanan, who in 1993 described multiculturalism as "an across-the-board assault on our Anglo-American heritage." Buchanan and other paleoconservatives argue that multiculturalism is the ideology of the modern managerial state, an ongoing regime that remains in power, regardless of what political party holds a majority. It acts in the name of abstract goals, such as equality or positive rights, and uses its claim of moral superiority, power of taxation and wealth redistribution to keep itself in power.

Buchanan has written:

We are attempting to convert a republic, European and Christian in its origins and character, into an egalitarian democracy of all the races, religions, cultures and tribes of planet Earth. We are turning America into a gargantuan replica of the U.N. General Assembly, a continental conclave of the most disparate and diverse peoples in all of history, who will have no common faith, no common moral code, no common language and no common culture. What, then, will hold us together?Multiculturalism has also been attacked through satire, such as the following proposition by John Derbyshire.

The Diversity Theorem: Groups of people from anywhere in the world, mixed together in any numbers and proportions whatsoever, will eventually settle down as a harmonious society, appreciating—nay, celebrating!—their differences... which will of course soon disappear entirely.This theorem is held to be false by Derbyshire and other paleoconservatives.

The late Lawrence Auster, another conservative critic of multiculturalism, argued that although multiculturalism was meant to promote the value of each culture, its real tendency had been to undermine US traditional majority culture. In Auster's view, multiculturalism tended to "downgrade our national culture while raising the status and power of other cultures."

He wrote:

The formal meaning of "diversity," "cultural equity," "gorgeous mosaic" and so on is a society in which many different cultures will live together in perfect equality and peace (i.e., a society that has never existed and never will exist); the real meaning of these slogans is that the power of the existing mainstream society to determine its own destiny shall be drastically reduced while the power of other groups, formerly marginal or external to that society, will be increased. In other words the U.S. must, in the name of diversity, abandon its particularity while the very groups making that demand shall hold on to theirs.Auster also wrote:

In demanding that non-European cultures, as cultures, be given the same importance as the European-American national culture, the multiculturalists are declaring that the non-European groups are unable or unwilling to assimilate as European immigrants have in the past, and that for the sake of these non-assimilating groups American society must be radically transformed. This ethnically and racially based rejection of the common American culture should lead thoughtful Americans to re-evaluate some contemporary assumptions about ethnicity and assimilation.Another critic of multiculturalism is the political theorist Brian Barry. In his 2002 book Culture and Equality: An Egalitarian Critique of Multiculturalism, he argues that some forms of multiculturalism can divide people, although they need to unite in order to fight for social justice.

Byron M. Roth, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Dowling College, has argued that multiculturalism is "profoundly undemocratic" and that multicultural countries can only be held together through state coercion. In his book The Perils of Diversity: Immigration and Human Nature, Roth writes:

From the perspective of inclusive fitness, unfamiliar others are potential free-riders and, out of a concern that they will be exploited by others, people reduce considerably their altruistic attitudes and behavior in a general way in more diverse communities. This loss of trust is a symptom of a breakdown in social cohesion and is surely a forerunner of the sort of ethnic conflict that is always likely to break out if allowed to do so. This is undoubtedly the reason why multicultural nation-states are forever promoting tolerance and ever more punitive sanctions for the expression of ethnic hostility, even going so far to as to discourage the expression of opinion about the reality of ethnic and racial differences. Currently these measures are directed at the host population when they express reservations about the wisdom of mass immigration, but this will surely change as it becomes ever more obvious that it is the presence of competing ethnic groups that is creating the tension and not the expressed reservations of the majority population. The real danger for modern democracies is that in their zeal to promote multicultural societies, they will be forced to resort to the means that have characterized all empires attempting to maintain their hegemony over disparate peoples.According to Roth, multiculturalism

... denies historical and scientific evidence that people differ in important biological and cultural ways that makes their assimilation into host countries problematic. It is also extreme in the viciousness with which it attacks those who differ on this issue. These attacks are accompanied by a very generalized and one-sided denigration of Western traditions and Western accomplishments, and claims that a collective guilt should be assumed by all Europeans (whites) for the sins of their forebears... In the semireligious formulation of this view, expiation of these sins can only come through an absolute benevolence toward the poor of the world whose suffering is claimed to be the result of the white race and its depredations. In practical terms this can only be accomplished through aid to Third World peoples and generous immigration policies that allow large numbers of people to escape the poverty of the Third World.Kevin B. MacDonald, a professor of psychology at California State University, Long Beach, has argued in his trilogy of books on Judaism that Jews have been prominent as main ideologues and promoters of multiculturalism in an attempt to end anti-semitism. MacDonald considers multiculturalism to be dangerous to the West, concluding in his Jack London Literary Prize acceptance speech:

[Given] that some ethnic groups—especially ones with high levels of ethnocentrism and mobilization—will undoubtedly continue to function as groups far into the foreseeable future, unilateral renunciation of ethnic loyalties by some groups means only their surrender and defeat—the Darwinian dead end of extinction. The future, then, like the past, will inevitably be a Darwinian competition in which ethnicity plays a very large role.

The alternative faced by Europeans throughout the Western world is to place themselves in a position of enormous vulnerability in which their destinies will be determined by other peoples, many of whom hold deep historically conditioned hatreds toward them. Europeans' promotion of their own displacement is the ultimate foolishness—an historical mistake of catastrophic proportions.Finally, multiculturalism and cultural relativism have been fiercely attacked by American social thinker Lloyd deMause, founder of psychohistory. DeMause's central argument is that, in the past, the astronomical infanticidal ratios among the tribes gives the lie to the claim that the diverse cultures are basically equal. DeMause wrote: "The best estimate I could make from the statistics was that in antiquity about half of all children born were killed by their caretakers, declining to about a third by later medieval times and to a very small percentage by the seventeenth century in Western Europe and America."

Diversity and social trust

Harvard professor of political science Robert D. Putnam conducted a nearly decade long study on how diversity affects social trust. He surveyed 26,200 people in 40 American communities, finding that when the data were adjusted for class, income and other factors, the more racially diverse a community is, the greater the loss of trust. People in diverse communities "don't trust the local mayor, they don't trust the local paper, they don't trust other people and they don't trust institutions," writes Putnam. In the presence of such ethnic diversity, Putnam maintains that[W]e hunker down. We act like turtles. The effect of diversity is worse than had been imagined. And it's not just that we don't trust people who are not like us. In diverse communities, we don't trust people who do look like us.Ethologist Frank Salter writes:

Relatively homogeneous societies invest more in public goods, indicating a higher level of public altruism. For example, the degree of ethnic homogeneity correlates with the government's share of gross domestic product as well as the average wealth of citizens. Case studies of the United States ... find that multi-ethnic societies are less charitable and less able to cooperate to develop public infrastructure. ... A recent multi-city study of municipal spending on public goods in the United States found that ethnically or racially diverse cities spend a smaller portion of their budgets and less per capita on public services than do the more homogeneous cities.

Yugoslavia

Before World War II, major tensions arose from the last, monarchist Yugoslavia's multi-ethnic makeup and absolute political and demographic domination of the Serbs. The Yugoslav wars that took place between 1991 and 2001 were characterized by bitter ethnic conflicts between the peoples of the former Yugoslavia, mostly between Serbs on the one side and Croats, Bosniaks or Albanians on the other; but also between Bosniaks and Croats in Bosnia and Macedonians and Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia.The conflict had its roots in various underlying political, economic and cultural problems, which provided justifications for political and religious leaders, and manifested itself through often provoked and artificial created ethnic and religious tensions.