Social and political organization varies between different cultures.

Culture (/ˈkʌltʃər/) is the social behavior and norms found in human societies. Culture is considered a central concept in anthropology, encompassing the range of phenomena that are transmitted through social learning in human societies. Cultural universals are found in all human societies; these include expressive forms like art, music, dance, ritual, religion, and technologies like tool usage, cooking, shelter, and clothing. The concept of material culture covers the physical expressions of culture, such as technology, architecture and art, whereas the immaterial aspects of culture such as principles of social organization (including practices of political organization and social institutions), mythology, philosophy, literature (both written and oral), and science comprise the intangible cultural heritage of a society.

In the humanities, one sense of culture as an attribute of the individual has been the degree to which they have cultivated a particular level of sophistication in the arts, sciences, education, or manners. The level of cultural sophistication has also sometimes been seen to distinguish civilizations from less complex societies. Such hierarchical perspectives on culture are also found in class-based distinctions between a high culture of the social elite and a low culture, popular culture, or folk culture of the lower classes, distinguished by the stratified access to cultural capital. In common parlance, culture is often used to refer specifically to the symbolic markers used by ethnic groups to distinguish themselves visibly from each other such as body modification, clothing or jewelry. Mass culture refers to the mass-produced and mass mediated forms of consumer culture that emerged in the 20th century. Some schools of philosophy, such as Marxism and critical theory, have argued that culture is often used politically as a tool of the elites to manipulate the lower classes and create a false consciousness, and such perspectives are common in the discipline of cultural studies. In the wider social sciences, the theoretical perspective of cultural materialism holds that human symbolic culture arises from the material conditions of human life, as humans create the conditions for physical survival, and that the basis of culture is found in evolved biological dispositions.

When used as a count noun, a "culture" is the set of customs, traditions, and values of a society or community, such as an ethnic group or nation. Culture is the set of knowledge acquired over time. In this sense, multiculturalism values the peaceful coexistence and mutual respect between different cultures inhabiting the same planet. Sometimes "culture" is also used to describe specific practices within a subgroup of a society, a subculture (e.g. "bro culture"), or a counterculture. Within cultural anthropology, the ideology and analytical stance of cultural relativism holds that cultures cannot easily be objectively ranked or evaluated because any evaluation is necessarily situated within the value system of a given culture.

Etymology

The modern term "culture" is based on a term used by the Ancient Roman orator Cicero in his Tusculanae Disputationes, where he wrote of a cultivation of the soul or "cultura animi," using an agricultural metaphor for the development of a philosophical soul, understood teleologically as the highest possible ideal for human development. Samuel Pufendorf took over this metaphor in a modern context, meaning something similar, but no longer assuming that philosophy was man's natural perfection. His use, and that of many writers after him, "refers to all the ways in which human beings overcome their original barbarism, and through artifice, become fully human."In 1986, philosopher Edward S. Casey wrote, "The very word culture meant 'place tilled' in Middle English, and the same word goes back to Latin colere, 'to inhabit, care for, till, worship' and cultus, 'A cult, especially a religious one.' To be cultural, to have a culture, is to inhabit a place sufficiently intensive to cultivate it—to be responsible for it, to respond to it, to attend to it caringly."

Culture described by Richard Velkley:

... originally meant the cultivation of the soul or mind, acquires most of its later modern meaning in the writings of the 18th-century German thinkers, who were on various levels developing Rousseau's criticism of "modern liberalism and Enlightenment". Thus a contrast between "culture" and "civilization" is usually implied in these authors, even when not expressed as such.In the words of anthropologist E.B. Tylor, it is "that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society." Alternatively, in a contemporary variant, "Culture is defined as a social domain that emphasizes the practices, discourses and material expressions, which, over time, express the continuities and discontinuities of social meaning of a life held in common.

The Cambridge English Dictionary states that culture is "the way of life, especially the general customs and beliefs, of a particular group of people at a particular time." Terror management theory posits that culture is a series of activities and worldviews that provide humans with the basis for perceiving themselves as "person[s] of worth within the world of meaning"—raising themselves above the merely physical aspects of existence, in order to deny the animal insignificance and death that Homo sapiens became aware of when they acquired a larger brain.

The word is used in a general sense as the evolved ability to categorize and represent experiences with symbols and to act imaginatively and creatively. This ability arose with the evolution of behavioral modernity in humans around 50,000 years ago, and is often thought to be unique to humans, although some other species have demonstrated similar, though much less complex, abilities for social learning. It is also used to denote the complex networks of practices and accumulated knowledge and ideas that is transmitted through social interaction and exist in specific human groups, or cultures, using the plural form.

Change

The Beatles

exemplified changing cultural dynamics, not only in music, but fashion

and lifestyle. Over a half century after their emergence, they continue

to have a worldwide cultural impact.

It has been estimated from archaeological data that the human capacity for cumulative culture emerged somewhere between 500 000 - 170 000 years ago.

Raimon Panikkar identified 29 ways in which cultural change can be brought about, including growth, development, evolution, involution, renovation, reconception, reform, innovation, revivalism, revolution, mutation, progress, diffusion, osmosis, borrowing, eclecticism, syncretism, modernization, indigenization, and transformation. In this context, modernization could be viewed as adoption of Enlightenment era beliefs and practices, such as science, rationalism, industry, commerce, democracy, and the notion of progress. Rein Raud, building on the work of Umberto Eco, Pierre Bourdieu and Jeffrey C. Alexander, has proposed a model of cultural change based on claims and bids, which are judged by their cognitive adequacy and endorsed or not endorsed by the symbolic authority of the cultural community in question.

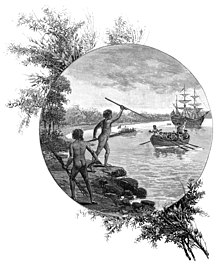

A 19th-century engraving showing Australian natives opposing the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1770

An Assyrian child wearing traditional clothing.

Cultural invention has come to mean any innovation that is new and found to be useful to a group of people and expressed in their behavior but which does not exist as a physical object. Humanity is in a global "accelerating culture change period," driven by the expansion of international commerce, the mass media, and above all, the human population explosion, among other factors. Culture repositioning means the reconstruction of the cultural concept of a society.

Cultures are internally affected by both forces encouraging change and forces resisting change. These forces are related to both social structures and natural events, and are involved in the perpetuation of cultural ideas and practices within current structures, which themselves are subject to change.

Social conflict and the development of technologies can produce changes within a society by altering social dynamics and promoting new cultural models, and spurring or enabling generative action. These social shifts may accompany ideological shifts and other types of cultural change. For example, the U.S. feminist movement involved new practices that produced a shift in gender relations, altering both gender and economic structures. Environmental conditions may also enter as factors. For example, after tropical forests returned at the end of the last ice age, plants suitable for domestication were available, leading to the invention of agriculture, which in turn brought about many cultural innovations and shifts in social dynamics.

Cultures are externally affected via contact between societies, which may also produce—or inhibit—social shifts and changes in cultural practices. War or competition over resources may impact technological development or social dynamics. Additionally, cultural ideas may transfer from one society to another, through diffusion or acculturation. In diffusion, the form of something (though not necessarily its meaning) moves from one culture to another. For example, hamburgers, fast food in the United States, seemed exotic when introduced into China. "Stimulus diffusion" (the sharing of ideas) refers to an element of one culture leading to an invention or propagation in another. "Direct borrowing," on the other hand, tends to refer to technological or tangible diffusion from one culture to another. Diffusion of innovations theory presents a research-based model of why and when individuals and cultures adopt new ideas, practices, and products.

Acculturation has different meanings, but in this context it refers to replacement of the traits of one culture with those of another, such as what happened to certain Native American tribes and to many indigenous peoples across the globe during the process of colonization. Related processes on an individual level include assimilation (adoption of a different culture by an individual) and transculturation. The transnational flow of culture has played a major role in merging different culture and sharing thoughts, ideas, and beliefs.

Early modern discourses

German Romanticism

Johann Herder called attention to national cultures.

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) formulated an individualist definition of "enlightenment" similar to the concept of bildung: "Enlightenment is man's emergence from his self-incurred immaturity." He argued that this immaturity comes not from a lack of understanding, but from a lack of courage to think independently. Against this intellectual cowardice, Kant urged: Sapere aude, "Dare to be wise!" In reaction to Kant, German scholars such as Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) argued that human creativity, which necessarily takes unpredictable and highly diverse forms, is as important as human rationality. Moreover, Herder proposed a collective form of bildung: "For Herder, Bildung was the totality of experiences that provide a coherent identity, and sense of common destiny, to a people."

Adolf Bastian developed a universal model of culture.

In 1795, the Prussian linguist and philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835) called for an anthropology that would synthesize Kant's and Herder's interests. During the Romantic era, scholars in Germany, especially those concerned with nationalist movements—such as the nationalist struggle to create a "Germany" out of diverse principalities, and the nationalist struggles by ethnic minorities against the Austro-Hungarian Empire—developed a more inclusive notion of culture as "worldview" (Weltanschauung). According to this school of thought, each ethnic group has a distinct worldview that is incommensurable with the worldviews of other groups. Although more inclusive than earlier views, this approach to culture still allowed for distinctions between "civilized" and "primitive" or "tribal" cultures.

In 1860, Adolf Bastian (1826–1905) argued for "the psychic unity of mankind." He proposed that a scientific comparison of all human societies would reveal that distinct worldviews consisted of the same basic elements. According to Bastian, all human societies share a set of "elementary ideas" (Elementargedanken); different cultures, or different "folk ideas" (Völkergedanken), are local modifications of the elementary ideas. This view paved the way for the modern understanding of culture. Franz Boas (1858–1942) was trained in this tradition, and he brought it with him when he left Germany for the United States.

English Romanticism

British poet and critic Matthew Arnold viewed "culture" as the cultivation of the humanist ideal.

In the 19th century, humanists such as English poet and essayist Matthew Arnold (1822–1888) used the word "culture" to refer to an ideal of individual human refinement, of "the best that has been thought and said in the world." This concept of culture is also comparable to the German concept of bildung: "...culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which most concern us, the best which has been thought and said in the world."

In practice, culture referred to an elite ideal and was associated with such activities as art, classical music, and haute cuisine. As these forms were associated with urban life, "culture" was identified with "civilization" (from lat. civitas, city). Another facet of the Romantic movement was an interest in folklore, which led to identifying a "culture" among non-elites. This distinction is often characterized as that between high culture, namely that of the ruling social group, and low culture. In other words, the idea of "culture" that developed in Europe during the 18th and early 19th centuries reflected inequalities within European societies.

British anthropologist Edward Tylor was one of the first English-speaking scholars to use the term culture in an inclusive and universal sense.

Matthew Arnold contrasted "culture" with anarchy; other Europeans, following philosophers Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, contrasted "culture" with "the state of nature." According to Hobbes and Rousseau, the Native Americans who were being conquered by Europeans from the 16th centuries on were living in a state of nature[citation needed]; this opposition was expressed through the contrast between "civilized" and "uncivilized." According to this way of thinking, one could classify some countries and nations as more civilized than others and some people as more cultured than others. This contrast led to Herbert Spencer's theory of Social Darwinism and Lewis Henry Morgan's theory of cultural evolution. Just as some critics have argued that the distinction between high and low cultures is really an expression of the conflict between European elites and non-elites, other critics have argued that the distinction between civilized and uncivilized people is really an expression of the conflict between European colonial powers and their colonial subjects.

Other 19th-century critics, following Rousseau, have accepted this differentiation between higher and lower culture, but have seen the refinement and sophistication of high culture as corrupting and unnatural developments that obscure and distort people's essential nature. These critics considered folk music (as produced by "the folk," i.e., rural, illiterate, peasants) to honestly express a natural way of life, while classical music seemed superficial and decadent. Equally, this view often portrayed indigenous peoples as "noble savages" living authentic and unblemished lives, uncomplicated and uncorrupted by the highly stratified capitalist systems of the West.

In 1870 the anthropologist Edward Tylor (1832–1917) applied these ideas of higher versus lower culture to propose a theory of the evolution of religion. According to this theory, religion evolves from more polytheistic to more monotheistic forms. In the process, he redefined culture as a diverse set of activities characteristic of all human societies. This view paved the way for the modern understanding of culture.

Anthropology

Petroglyphs in modern-day Gobustan, Azerbaijan, dating back to 10,000 BCE and indicating a thriving culture

Although anthropologists worldwide refer to Tylor's definition of culture, in the 20th century "culture" emerged as the central and unifying concept of American anthropology, where it most commonly refers to the universal human capacity to classify and encode human experiences symbolically, and to communicate symbolically encoded experiences socially. American anthropology is organized into four fields, each of which plays an important role in research on culture: biological anthropology, linguistic anthropology, cultural anthropology, and in the United States, archaeology. The term Kulturbrille, or "culture glasses," coined by German American anthropologist Franz Boas, refers to the "lenses" through which we see our own countries. Martin Lindstrom asserts that Kulturbrille, which allow us to make sense of the culture we inhabit, also "can blind us to things outsiders pick up immediately."

Sociology

The sociology of culture concerns culture as manifested in society. For sociologist Georg Simmel (1858–1918), culture referred to "the cultivation of individuals through the agency of external forms which have been objectified in the course of history." As such, culture in the sociological field can be defined as the ways of thinking, the ways of acting, and the material objects that together shape a people's way of life. Culture can be any of two types, non-material culture or material culture. Non-material culture refers to the non-physical ideas that individuals have about their culture, including values, belief systems, rules, norms, morals, language, organizations, and institutions, while material culture is the physical evidence of a culture in the objects and architecture they make or have made. The term tends to be relevant only in archeological and anthropological studies, but it specifically means all material evidence which can be attributed to culture, past or present.Cultural sociology first emerged in Weimar Germany (1918–1933), where sociologists such as Alfred Weber used the term Kultursoziologie (cultural sociology). Cultural sociology was then "reinvented" in the English-speaking world as a product of the "cultural turn" of the 1960s, which ushered in structuralist and postmodern approaches to social science. This type of cultural sociology may be loosely regarded as an approach incorporating cultural analysis and critical theory. Cultural sociologists tend to reject scientific methods, instead hermeneutically focusing on words, artifacts and symbols. "Culture" has since become an important concept across many branches of sociology, including resolutely scientific fields like social stratification and social network analysis. As a result, there has been a recent influx of quantitative sociologists to the field. Thus, there is now a growing group of sociologists of culture who are, confusingly, not cultural sociologists. These scholars reject the abstracted postmodern aspects of cultural sociology, and instead look for a theoretical backing in the more scientific vein of social psychology and cognitive science.

Early researchers and development of cultural sociology

The sociology of culture grew from the intersection between sociology (as shaped by early theorists like Marx, Durkheim, and Weber) with the growing discipline of anthropology, wherein researchers pioneered ethnographic strategies for describing and analyzing a variety of cultures around the world. Part of the legacy of the early development of the field lingers in the methods (much of cultural sociological research is qualitative), in the theories (a variety of critical approaches to sociology are central to current research communities), and in the substantive focus of the field. For instance, relationships between popular culture, political control, and social class were early and lasting concerns in the field.Cultural studies

In the United Kingdom, sociologists and other scholars influenced by Marxism such as Stuart Hall (1932–2014) and Raymond Williams (1921–1988) developed cultural studies. Following nineteenth-century Romantics, they identified "culture" with consumption goods and leisure activities (such as art, music, film, food, sports, and clothing). They saw patterns of consumption and leisure as determined by relations of production, which led them to focus on class relations and the organization of production.In the United States, cultural studies focuses largely on the study of popular culture; that is, on the social meanings of mass-produced consumer and leisure goods. Richard Hoggart coined the term in 1964 when he founded the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies or CCCS. It has since become strongly associated with Stuart Hall, who succeeded Hoggart as Director. Cultural studies in this sense, then, can be viewed as a limited concentration scoped on the intricacies of consumerism, which belongs to a wider culture sometimes referred to as "Western civilization" or "globalism."

From the 1970s onward, Stuart Hall's pioneering work, along with that of his colleagues Paul Willis, Dick Hebdige, Tony Jefferson, and Angela McRobbie, created an international intellectual movement. As the field developed, it began to combine political economy, communication, sociology, social theory, literary theory, media theory, film/video studies, cultural anthropology, philosophy, museum studies, and art history to study cultural phenomena or cultural texts. In this field researchers often concentrate on how particular phenomena relate to matters of ideology, nationality, ethnicity, social class, and/or gender. Cultural studies is concerned with the meaning and practices of everyday life. These practices comprise the ways people do particular things (such as watching television, or eating out) in a given culture. It also studies the meanings and uses people attribute to various objects and practices. Specifically, culture involves those meanings and practices held independently of reason. Watching television in order to view a public perspective on a historical event should not be thought of as culture, unless referring to the medium of television itself, which may have been selected culturally; however, schoolchildren watching television after school with their friends in order to "fit in" certainly qualifies, since there is no grounded reason for one's participation in this practice.

In the context of cultural studies, the idea of a text includes not only written language, but also films, photographs, fashion or hairstyles: the texts of cultural studies comprise all the meaningful artifacts of culture. Similarly, the discipline widens the concept of "culture." "Culture" for a cultural-studies researcher not only includes traditional high culture (the culture of ruling social groups) and popular culture, but also everyday meanings and practices. The last two, in fact, have become the main focus of cultural studies. A further and recent approach is comparative cultural studies, based on the disciplines of comparative literature and cultural studies.

Scholars in the United Kingdom and the United States developed somewhat different versions of cultural studies after the late 1970s. The British version of cultural studies had originated in the 1950s and 1960s, mainly under the influence of Richard Hoggart, E. P. Thompson, and Raymond Williams, and later that of Stuart Hall and others at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham. This included overtly political, left-wing views, and criticisms of popular culture as "capitalist" mass culture; it absorbed some of the ideas of the Frankfurt School critique of the "culture industry" (i.e. mass culture). This emerges in the writings of early British cultural-studies scholars and their influences: see the work of (for example) Raymond Williams, Stuart Hall, Paul Willis, and Paul Gilroy.

In the United States, Lindlof and Taylor write, "Cultural studies [were] grounded in a pragmatic, liberal-pluralist tradition." The American version of cultural studies initially concerned itself more with understanding the subjective and appropriative side of audience reactions to, and uses of, mass culture; for example, American cultural-studies advocates wrote about the liberatory aspects of fandom. The distinction between American and British strands, however, has faded. Some researchers, especially in early British cultural studies, apply a Marxist model to the field. This strain of thinking has some influence from the Frankfurt School, but especially from the structuralist Marxism of Louis Althusser and others. The main focus of an orthodox Marxist approach concentrates on the production of meaning. This model assumes a mass production of culture and identifies power as residing with those producing cultural artifacts. In a Marxist view, those who control the means of production (the economic base) essentially control a culture. Other approaches to cultural studies, such as feminist cultural studies and later American developments of the field, distance themselves from this view. They criticize the Marxist assumption of a single, dominant meaning, shared by all, for any cultural product. The non-Marxist approaches suggest that different ways of consuming cultural artifacts affect the meaning of the product. This view comes through in the book Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman (by Paul du Gay et al.), which seeks to challenge the notion that those who produce commodities control the meanings that people attribute to them. Feminist cultural analyst, theorist, and art historian Griselda Pollock contributed to cultural studies from viewpoints of art history and psychoanalysis. The writer Julia Kristeva is among influential voices at the turn of the century, contributing to cultural studies from the field of art and psychoanalytical French feminism.

Petrakis and Kostis (2013) divide cultural background variables into two main groups:

- The first group covers the variables that represent the "efficiency orientation" of the societies: performance orientation, future orientation, assertiveness, power distance and uncertainty avoidance.

- The second covers the variables that represent the "social orientation" of societies, i.e., the attitudes and lifestyles of their members. These variables include gender egalitarianism, institutional collectivism, in-group collectivism and human orientation.