Electrical impedance is the measure of the opposition that a circuit presents to a current when a voltage is applied. The term complex impedance may be used interchangeably.

Quantitatively, the impedance of a two-terminal circuit element is the ratio of the complex representation of a sinusoidal voltage between its terminals to the complex representation of the current flowing through it. In general, it depends upon the frequency of the sinusoidal voltage.

Impedance extends the concept of resistance to AC circuits, and possesses both magnitude and phase, unlike resistance, which has only magnitude. When a circuit is driven with direct current (DC), there is no distinction between impedance and resistance; the latter can be thought of as impedance with zero phase angle.

The notion of impedance is useful for performing AC analysis of electrical networks, because it allows relating sinusoidal voltages and currents by a simple linear law. In multiple port networks, the two-terminal definition of impedance is inadequate, but the complex voltages at the ports and the currents flowing through them are still linearly related by the impedance matrix.

Impedance is a complex number, with the same units as resistance, for which the SI unit is the ohm (Ω). Its symbol is usually Z, and it may be represented by writing its magnitude and phase in the form |Z|∠θ. However, cartesian complex number representation is often more powerful for circuit analysis purposes.

The reciprocal of impedance is admittance, whose SI unit is the siemens, formerly called mho.

Impedance extends the concept of resistance to AC circuits, and possesses both magnitude and phase, unlike resistance, which has only magnitude. When a circuit is driven with direct current (DC), there is no distinction between impedance and resistance; the latter can be thought of as impedance with zero phase angle.

The notion of impedance is useful for performing AC analysis of electrical networks, because it allows relating sinusoidal voltages and currents by a simple linear law. In multiple port networks, the two-terminal definition of impedance is inadequate, but the complex voltages at the ports and the currents flowing through them are still linearly related by the impedance matrix.

Impedance is a complex number, with the same units as resistance, for which the SI unit is the ohm (Ω). Its symbol is usually Z, and it may be represented by writing its magnitude and phase in the form |Z|∠θ. However, cartesian complex number representation is often more powerful for circuit analysis purposes.

The reciprocal of impedance is admittance, whose SI unit is the siemens, formerly called mho.

Introduction

In addition to resistance as seen in DC circuits, impedance in AC circuits includes the effects of the induction of voltages in conductors by the magnetic fields (inductance), and the electrostatic storage of charge induced by voltages between conductors (capacitance). The impedance caused by these two effects is collectively referred to as reactance and forms the imaginary part of complex impedance whereas resistance forms the real part.

Impedance is defined as the frequency domain ratio of the voltage to the current. In other words, it is the voltage–current ratio for a single complex exponential at a particular frequency ω.

For a sinusoidal current or voltage input, the polar form of the complex impedance relates the amplitude and phase of the voltage and current. In particular:

- The magnitude of the complex impedance is the ratio of the voltage amplitude to the current amplitude;

- the phase of the complex impedance is the phase shift by which the current lags the voltage.

Complex impedance

A graphical representation of the complex impedance plane

The impedance of a two-terminal circuit element is represented as a complex quantity . The polar form conveniently captures both magnitude and phase characteristics as

In Cartesian form, impedance is defined as

Where it is needed to add or subtract impedances, the cartesian form is more convenient; but when quantities are multiplied or divided, the calculation becomes simpler if the polar form is used. A circuit calculation, such as finding the total impedance of two impedances in parallel, may require conversion between forms several times during the calculation. Conversion between the forms follows the normal conversion rules of complex numbers.

Complex voltage and current

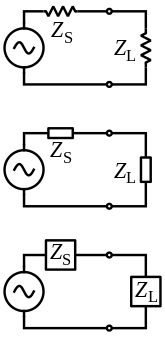

Generalized impedances in a circuit can be drawn with the same symbol as a resistor (US ANSI or DIN Euro) or with a labeled box.

To simplify calculations, sinusoidal voltage and current waves are commonly represented as complex-valued functions of time denoted as and .

Validity of complex representation

This representation using complex exponentials may be justified by noting that (by Euler's formula):Ohm's law

The meaning of electrical impedance can be understood by substituting it into Ohm's law. Assuming a two-terminal circuit element with impedance is driven by a sinusoidal voltage or current as above, there holds

Just as impedance extends Ohm's law to cover AC circuits, other results from DC circuit analysis, such as voltage division, current division, Thévenin's theorem and Norton's theorem, can also be extended to AC circuits by replacing resistance with impedance.

Phasors

A phasor is represented by a constant complex number, usually expressed in exponential form, representing the complex amplitude (magnitude and phase) of a sinusoidal function of time. Phasors are used by electrical engineers to simplify computations involving sinusoids, where they can often reduce a differential equation problem to an algebraic one.The impedance of a circuit element can be defined as the ratio of the phasor voltage across the element to the phasor current through the element, as determined by the relative amplitudes and phases of the voltage and current. This is identical to the definition from Ohm's law given above, recognising that the factors of cancel.

Device examples

Resistor

The phase angles in the equations for the impedance of capacitors and inductors indicate that the voltage across a capacitor lags the current through it by a phase of , while the voltage across an inductor leads the current through it by . The identical voltage and current amplitudes indicate that the magnitude of the impedance is equal to one.

The impedance of an ideal resistor is purely real and is called resistive impedance:

Inductor and capacitor

Ideal inductors and capacitors have a purely imaginary reactive impedance:the impedance of inductors increases as frequency increases;

Note the following identities for the imaginary unit and its reciprocal:

Deriving the device-specific impedances

What follows below is a derivation of impedance for each of the three basic circuit elements: the resistor, the capacitor, and the inductor. Although the idea can be extended to define the relationship between the voltage and current of any arbitrary signal, these derivations assume sinusoidal signals. In fact, this applies to any arbitrary periodic signals, because these can be approximated as a sum of sinusoids through Fourier analysis.Resistor

For a resistor, there is the relationConsidering the voltage signal to be

This result is commonly expressed as

Capacitor

For a capacitor, there is the relation:Inductor

For the inductor, we have the relation (from Faraday's law):Generalised s-plane impedance

Impedance defined in terms of jω can strictly be applied only to circuits that are driven with a steady-state AC signal. The concept of impedance can be extended to a circuit energised with any arbitrary signal by using complex frequency instead of jω. Complex frequency is given the symbol s and is, in general, a complex number. Signals are expressed in terms of complex frequency by taking the Laplace transform of the time domain expression of the signal. The impedance of the basic circuit elements in this more general notation is as follows:| Element | Impedance expression |

|---|---|

| Resistor | |

| Inductor | |

| Capacitor |

For a DC circuit, this simplifies to s = 0. For a steady-state sinusoidal AC signal s = jω.

Resistance vs reactance

Resistance and reactance together determine the magnitude and phase of the impedance through the following relations:Resistance

Resistance is the real part of impedance; a device with a purely resistive impedance exhibits no phase shift between the voltage and current.Reactance

Reactance is the imaginary part of the impedance; a component with a finite reactance induces a phase shift between the voltage across it and the current through it.Capacitive reactance

A capacitor has a purely reactive impedance that is inversely proportional to the signal frequency. A capacitor consists of two conductors separated by an insulator, also known as a dielectric.At low frequencies, a capacitor approaches an open circuit so no current flows through it.

A DC voltage applied across a capacitor causes charge to accumulate on one side; the electric field due to the accumulated charge is the source of the opposition to the current. When the potential associated with the charge exactly balances the applied voltage, the current goes to zero.

Driven by an AC supply, a capacitor accumulates only a limited charge before the potential difference changes sign and the charge dissipates. The higher the frequency, the less charge accumulates and the smaller the opposition to the current.

Inductive reactance

Inductive reactance is proportional to the signal frequency and the inductance .Total reactance

The total reactance is given by- (note that is negative)

Combining impedances

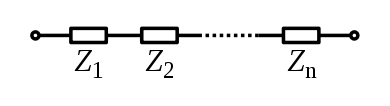

The total impedance of many simple networks of components can be calculated using the rules for combining impedances in series and parallel. The rules are identical to those for combining resistances, except that the numbers in general are complex numbers. The general case, however, requires equivalent impedance transforms in addition to series and parallel.Series combination

For components connected in series, the current through each circuit element is the same; the total impedance is the sum of the component impedances.

Parallel combination

For components connected in parallel, the voltage across each circuit element is the same; the ratio of currents through any two elements is the inverse ratio of their impedances.Hence the inverse total impedance is the sum of the inverses of the component impedances:

Measurement

The measurement of the impedance of devices and transmission lines is a practical problem in radio technology and other fields. Measurements of impedance may be carried out at one frequency, or the variation of device impedance over a range of frequencies may be of interest. The impedance may be measured or displayed directly in ohms, or other values related to impedance may be displayed; for example, in a radio antenna, the standing wave ratio or reflection coefficient may be more useful than the impedance alone. The measurement of impedance requires the measurement of the magnitude of voltage and current, and the phase difference between them. Impedance is often measured by "bridge" methods, similar to the direct-current Wheatstone bridge; a calibrated reference impedance is adjusted to balance off the effect of the impedance of the device under test. Impedance measurement in power electronic devices may require simultaneous measurement and provision of power to the operating device.The impedance of a device can be calculated by complex division of the voltage and current. The impedance of the device can be calculated by applying a sinusoidal voltage to the device in series with a resistor, and measuring the voltage across the resistor and across the device. Performing this measurement by sweeping the frequencies of the applied signal provides the impedance phase and magnitude.

The use of an impulse response may be used in combination with the fast Fourier transform (FFT) to rapidly measure the electrical impedance of various electrical devices.

The LCR meter (Inductance (L), Capacitance (C), and Resistance (R)) is a device commonly used to measure the inductance, resistance and capacitance of a component; from these values, the impedance at any frequency can be calculated.

![\ \cos(\omega t+\phi )={\frac {1}{2}}{\Big [}e^{j(\omega t+\phi )}+e^{-j(\omega t+\phi )}{\Big ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ac6d2d678fbcb897277792546ef55f422d17c2dc)