From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Learning is the process of acquiring new, or modifying existing,

knowledge,

behaviors,

skills,

values, or

preferences. The ability to learn is possessed by humans, animals, and some

machines; there is also evidence for some kind of learning in some plants.

Some learning is immediate, induced by a single event (e.g. being

burned by a hot stove), but much skill and knowledge accumulates from

repeated experiences. The changes induced by learning often last a

lifetime, and it is hard to distinguish learned material that seems to

be "lost" from that which cannot be retrieved.

Human learning begins before birth and continues until death as a

consequence of ongoing interactions between person and environment. The

nature and processes involved in learning are studied in many fields,

including

educational psychology,

neuropsychology,

experimental psychology, and

pedagogy.

Research in such fields has led to the identification of various sorts

of learning. For example, learning may occur as a result of

habituation, or

classical conditioning,

operant conditioning or as a result of more complex activities such as

play, seen only in relatively intelligent animals. Learning may occur

consciously or without conscious awareness. Learning that an aversive event can't be avoided nor escaped may result in a condition called

learned helplessness. There is evidence for human behavioral learning

prenatally, in which

habituation has been observed as early as 32 weeks into

gestation, indicating that the

central nervous system is sufficiently developed and primed for learning and

memory to occur very early on in

development.

Play has been approached by several theorists as the first form

of learning. Children experiment with the world, learn the rules, and

learn to interact through play.

Lev Vygotsky

agrees that play is pivotal for children's development, since they make

meaning of their environment through playing educational games.

Types

Non-associative learning

Non-associative learning

refers to "a relatively permanent change in the strength of response to

a single stimulus due to repeated exposure to that stimulus. Changes

due to such factors as

sensory adaptation,

fatigue, or injury do not qualify as non-associative learning."

Non-associative learning can be divided into

habituation and

sensitization.

Habituation

Habituation is an example of non-associative learning in which

the strength or probability of a response diminishes when the stimulus

is repeated. The response is typically a reflex or unconditioned

response. Thus, habituation must be distinguished from

extinction,

which is an associative process. In operant extinction, for example, a

response declines because it is no longer followed by a reward. An

example of habituation can be seen in small song birds—if a stuffed

owl (or similar

predator)

is put into the cage, the birds initially react to it as though it were

a real predator. Soon the birds react less, showing habituation. If

another stuffed owl is introduced (or the same one removed and

re-introduced), the birds react to it again as though it were a

predator, demonstrating that it is only a very specific stimulus that is

habituated to (namely, one particular unmoving owl in one place). The

habituation process is faster for stimuli that occur at a high rather

than for stimuli that occur at a low rate as well as for the weak and

strong stimuli, respectively. Habituation has been shown in essentially every species of animal, as well as the sensitive plant

Mimosa pudica and the large protozoan

Stentor coeruleus. This concept acts in direct opposition to sensitization.

Sensitization

Sensitization is an example of non-associative learning in

which the progressive amplification of a response follows repeated

administrations of a

stimulus (Bell et al., 1995).

This is based on the notion that a defensive reflex to a stimulus such

as withdrawal or escape becomes stronger after the exposure to a

different harmful or threatening stimulus.

An everyday example of this mechanism is the repeated tonic stimulation

of peripheral nerves that occurs if a person rubs their arm

continuously. After a while, this stimulation creates a warm sensation

that eventually turns painful. The pain results from the progressively

amplified synaptic response of the peripheral nerves warning that the

stimulation is harmful. Sensitisation is thought to underlie both adaptive as well as maladaptive learning processes in the organism.

Active learning

Active learning occurs when a person takes control of his/her

learning experience. Since understanding information is the key aspect

of learning, it is important for learners to recognize what they

understand and what they do not. By doing so, they can monitor their own

mastery of subjects. Active learning encourages learners to have an

internal dialogue in which they verbalize understandings. This and other

meta-cognitive strategies can be taught to a child over time. Studies

within

metacognition have proven the value in active learning, claiming that the learning is usually at a stronger level as a result.

In addition, learners have more incentive to learn when they have

control over not only how they learn but also what they learn. Active learning is a key characteristic of

student-centered learning. Conversely,

passive learning and

direct instruction are characteristics of teacher-centered learning (or

traditional education).

The

research works on the human learning process as a

complex adaptive system developed by

Peter Belohlavek showed that it is the concept that the individual has that drives the accommodation process to assimilate new knowledge in the

long-term memory, defining learning as an intrinsically freedom-oriented and active process. As a

student-centered learning

approach, the unicist reflection driven learning installs adaptive

knowledge objects in the mind of the learner based on a cyclic process

of: “action-reflection-action” to foster an

adaptive behavior.

Associative learning

Associative learning is the process by which a person or animal learns an association between two stimuli or events.

In classical conditioning a previously neutral stimulus is repeatedly

paired with a reflex eliciting stimulus until eventually the neutral

stimulus elicits a response on its own. In operant conditioning, a

behavior that is reinforced or punished in the presence of a stimulus

becomes more or less likely to occur in the presence of that stimulus.

Operant conditioning

In

operant conditioning, a reinforcement (by reward) or

instead a punishment given after a given behavior, change the frequency

and/or form of that behavior. Stimulus present when the

behavior/consequence occurs come to control these behavior

modifications.

Classical conditioning

The typical paradigm for

classical conditioning involves

repeatedly pairing an unconditioned stimulus (which unfailingly evokes a

reflexive response) with another previously neutral stimulus (which

does not normally evoke the response). Following conditioning, the

response occurs both to the unconditioned stimulus and to the other,

unrelated stimulus (now referred to as the "conditioned stimulus"). The

response to the conditioned stimulus is termed a

conditioned response. The classic example is

Ivan Pavlov and his dogs.

Pavlov fed his dogs meat powder, which naturally made the dogs

salivate—salivating is a reflexive response to the meat powder. Meat

powder is the unconditioned stimulus (US) and the salivation is the

unconditioned response (UR). Pavlov rang a bell before presenting the

meat powder. The first time Pavlov rang the bell, the neutral stimulus,

the dogs did not salivate, but once he put the meat powder in their

mouths they began to salivate. After numerous pairings of bell and food,

the dogs learned that the bell signaled that food was about to come,

and began to salivate when they heard the bell. Once this occurred, the

bell became the conditioned stimulus (CS) and the salivation to the bell

became the conditioned response (CR). Classical conditioning has been

demonstrated in many species. For example, it is seen in honeybees, in

the

proboscis extension reflex paradigm. It was recently also demonstrated in garden pea plants.

Another influential person in the world of classical conditioning is

John B. Watson. Watson's work was very influential and paved the way for

B.F. Skinner's

radical behaviorism. Watson's behaviorism (and philosophy of science)

stood in direct contrast to Freud and other accounts based largely on

introspection. Watson's view was that the introspective method was too

subjective, and that we should limit the study of human development to

directly observable behaviors. In 1913, Watson published the article

"Psychology as the Behaviorist Views," in which he argued that

laboratory studies should serve psychology best as a science. Watson's

most famous, and controversial, experiment, "

Little Albert", where he demonstrated how psychologists can account for the learning of emotion through classical conditioning principles.

Observational learning

Observational learning is learning that occurs through

observing the behavior of others. It is a form of social learning which

takes various forms, based on various processes. In humans, this form of

learning seems to not need reinforcement to occur, but instead,

requires a social model such as a parent, sibling, friend, or teacher

with surroundings.

Imprinting

Imprinting is a kind of learning occurring at a particular

life stage that is rapid and apparently independent of the consequences

of behavior. In filial imprinting, young animals, particularly birds,

form an association with another individual or in some cases, an object,

that they respond to as they would to a parent. In 1935, the Austrian

Zoologist Konrad Lorenz discovered that certain birds follow and form a

bond if the object makes sounds.

Play

Play generally describes behavior with no particular end in

itself, but that improves performance in similar future situations. This

is seen in a wide variety of vertebrates besides humans, but is mostly

limited to

mammals and

birds.

Cats are known to play with a ball of string when young, which gives

them experience with catching prey. Besides inanimate objects, animals

may play with other members of their own species or other animals, such

as

orcas playing with seals they have caught. Play involves a significant cost to animals, such as increased vulnerability to

predators and the risk of

injury and possibly

infection. It also consumes

energy,

so there must be significant benefits associated with play for it to

have evolved. Play is generally seen in younger animals, suggesting a

link with learning. However, it may also have other benefits not

associated directly with learning, for example improving

physical fitness.

Play, as it pertains to humans as a form of learning is central

to a child's learning and development. Through play, children learn

social skills such as sharing and collaboration. Children develop

emotional skills such as learning to deal with the emotion of anger,

through play activities. As a form of learning, play also facilitates

the development of thinking and language skills in children.

There are five types of play:

- sensorimotor play aka functional play, characterized by repetition of activity

- role play occurs starting at the age of 3

- rule-based play where authoritative prescribed codes of conduct are primary

- construction play involves experimentation and building

- movement play aka physical play

These five types of play are often intersecting. All types of play generate thinking and

problem-solving skills in children. Children learn to think creatively when they learn through play.

Specific activities involved in each type of play change over time as

humans progress through the lifespan. Play as a form of learning, can

occur solitarily, or involve interacting with others.

Enculturation

Enculturation is the process by which people learn values and behaviors that are appropriate or necessary in their surrounding culture. Parents, other adults, and peers shape the individual's understanding of these values. If successful, enculturation results in competence in the language, values and rituals of the culture. This is different from

acculturation, where a person adopts the values and societal rules of a culture different from their native one.

Multiple examples of enculturation can be found cross-culturally.

Collaborative practices in the Mazahua people have shown that

participation in everyday interaction and later learning activities

contributed to enculturation rooted in nonverbal social experience.

As the children participated in everyday activities, they learned the

cultural significance of these interactions. The collaborative and

helpful behaviors exhibited by Mexican and Mexican-heritage children is a

cultural practice known as being "acomedido". Chillihuani girls in Peru described themselves as weaving constantly, following behavior shown by the other adults.

Episodic learning

Episodic learning is a change in behavior that occurs as a result of an event.

For example, a fear of dogs that follows being bitten by a dog is

episodic learning. Episodic learning is so named because events are

recorded into

episodic memory, which is one of the three forms of explicit learning and retrieval, along with perceptual memory and

semantic memory.

Episodic memory remembers events and history that are embedded in

experience and this is distinguished from semantic memory, which

attempts to extract facts out of their experiential context or - as some describe - a timeless organization of knowledge. For instance, if a person remembers the

Grand Canyon

from a recent visit, it is an episodic memory. He would use semantic

memory to answer someone who would ask him information such as where the

Grand Canyon is. A study revealed that humans are very accurate in the

recognition of episodic memory even without deliberate intention to

memorize it. This is said to indicate a very large storage capacity of the brain for things that people pay attention to.

Multimedia learning

Multimedia learning is where a person uses both auditory and visual stimuli to learn information (

Mayer 2001). This type of learning relies on

dual-coding theory (

Paivio 1971).

E-learning and augmented learning

Electronic learning or e-learning is computer-enhanced learning. A specific and always more diffused e-learning is

mobile learning (m-learning), which uses different mobile telecommunication equipment, such as

cellular phones.

When a learner interacts with the e-learning environment, it's called

augmented learning.

By adapting to the needs of individuals, the context-driven instruction

can be dynamically tailored to the learner's natural environment.

Augmented digital content may include text, images, video, audio (music

and voice). By personalizing instruction, augmented learning has been

shown to improve learning performance for a lifetime.

Moore (1989) purported that three core types of interaction are necessary for quality, effective online learning:

- learner–learner (i.e. communication between and among peers with or without the teacher present),

- learner–instructor (i.e. student teacher communication), and

- learner–content (i.e. intellectually interacting with content that

results in changes in learners' understanding, perceptions, and

cognitive structures).

In his theory of transactional distance, Moore (1993)

contented that structure and interaction or dialogue bridge the gap in

understanding and communication that is created by geographical

distances (known as transactional distance).

Rote learning

Rote learning is

memorizing information so that it can be

recalled by the learner exactly the way it was read or heard. The major technique used for rote learning is

learning by repetition,

based on the idea that a learner can recall the material exactly (but

not its meaning) if the information is repeatedly processed. Rote

learning is used in diverse areas, from mathematics to music to

religion. Although it has been criticized by some educators, rote

learning is a necessary precursor to meaningful learning.

Meaningful learning

Meaningful learning is the concept that learned knowledge

(e.g., a fact) is fully understood to the extent that it relates to

other knowledge. To this end, meaningful learning contrasts with

rote learning

in which information is acquired without regard to understanding.

Meaningful learning, on the other hand, implies there is a comprehensive

knowledge of the context of the facts learned.

Informal learning

Informal learning occurs through the experience of day-to-day

situations (for example, one would learn to look ahead while walking

because of the danger inherent in not paying attention to where one is

going). It is learning from life, during a meal at table with parents,

play, exploring, etc.

Formal learning

Formal learning is learning that takes place within a

teacher-student relationship, such as in a school system. The term

formal learning has nothing to do with the formality of the learning,

but rather the way it is directed and organized. In formal learning, the

learning or training departments set out the goals and objectives of

the learning.

Nonformal learning

Nonformal learning is organized learning outside the formal

learning system. For example, learning by coming together with people

with similar interests and exchanging viewpoints, in clubs or in

(international) youth organizations, workshops.

Nonformal learning and combined approaches

The

educational system may use a combination of formal, informal, and

nonformal learning methods. The UN and EU recognize these different

forms of learning (cf. links below). In some schools, students can get

points that count in the formal-learning systems if they get work done

in informal-learning circuits. They may be given time to assist

international youth workshops and training courses, on the condition

they prepare, contribute, share and can prove this offered valuable new

insight, helped to acquire new skills, a place to get experience in

organizing,

teaching, etc.

To learn a skill, such as solving a

Rubik's Cube quickly, several factors come into play at once:

- Reading directions helps a player learn the patterns that solve the Rubik's Cube.

- Practicing the moves repeatedly helps build "muscle memory" and speed.

- Thinking critically about moves helps find shortcuts, which speeds future attempts.

- Observing the Rubik's Cube's six colors help anchor solutions in the mind.

- Revisiting the cube occasionally helps retain the skill.

Tangential learning

Tangential learning

is the process by which people self-educate if a topic is exposed to

them in a context that they already enjoy. For example, after playing a

music-based video game, some people may be motivated to learn how to

play a real instrument, or after watching a TV show that references

Faust and Lovecraft, some people may be inspired to read the original

work.

Self-education can be improved with systematization. According to

experts in natural learning,

self-oriented learning training has proven an effective tool for

assisting independent learners with the natural phases of learning.

Extra Credits writer and game designer James Portnow was the first to suggest games as a potential venue for "tangential learning". Mozelius

et al.

points out that intrinsic integration of learning content seems to be a

crucial design factor, and that games that include modules for further

self-studies tend to present good results. The built-in encyclopedias in

the

Civilization

games are presented as an example - by using these modules gamers can

dig deeper for knowledge about historical events in the gameplay. The

importance of rules that regulate learning modules and game experience

is discussed by Moreno, C., in a case study about the mobile game

Kiwaka (Q55416666). In this game, developed by Landka in collaboration with

ESA and

ESO, game progress is rewarded with educational content, as opposed to traditional

education games where learning activities are rewarded with gameplay.

Incidental learning

In

incidental teaching

learning is not planned by the instructor or the student, it occurs as a

byproduct of another activity — an experience, observation,

self-reflection, interaction, unique event, or common routine task. This

learning happens in addition to or apart from the instructor's plans

and the student's expectations. An example of incidental teaching is

when the instructor places a train set on top of a cabinet. If the child

points or walks towards the cabinet, the instructor prompts the student

to say “train.” Once the student says “train,” he gets access to the

train set.

Here are some steps most commonly used in incidental teaching:

- An instructor will arrange the learning environment so that

necessary materials are within the student's sight, but not within his

reach, thus impacting his motivation to seek out those materials.

- An instructor waits for the student to initiate engagement.

- An instructor prompts the student to respond if needed.

- An instructor allows access to an item/activity contingent on a correct response from the student.

- The instructor fades out the prompting process over a period of time and subsequent trials.

Incidental learning is an occurrence that is not generally accounted

for using the traditional methods of instructional objectives and

outcomes assessment. This type of learning occurs in part as a product

of social interaction and active involvement in both online and onsite

courses. Research implies that some un-assessed aspects of onsite and

online learning challenge the equivalency of education between the two

modalities. Both onsite and online learning have distinct advantages

with traditional on-campus students experiencing higher degrees of

incidental learning in three times as many areas as online students.

Additional research is called for to investigate the implications of

these findings both conceptually and pedagogically.

Domains

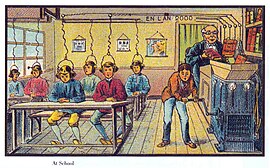

Future school (1901 or 1910)

Benjamin Bloom has suggested three domains of learning:

- Cognitive: To recall, calculate, discuss, analyze, problem solve, etc.

- Psychomotor: To dance, swim, ski, dive, drive a car, ride a bike, etc.

- Affective: To like something or someone, love, appreciate, fear, hate, worship, etc.

These domains are not mutually exclusive. For example, in learning to play

chess,

the person must learn the rules (cognitive domain)—but must also learn

how to set up the chess pieces and how to properly hold and move a chess

piece (psychomotor). Furthermore, later in the game the person may even

learn to love the game itself, value its applications in life, and

appreciate its

history (affective domain).

Transfer

Transfer

of learning is the application of skill, knowledge or understanding to

resolve a novel problem or situation that happens when certain

conditions are fulfilled. Research indicates that learning transfer is

infrequent; most common when "... cued, primed, and guided..." and has sought to clarify what it is, and how it might be promoted through instruction.

Over the history of its discourse, various hypotheses and

definitions have been advanced. First, it is speculated that different

types of transfer exist, including: near transfer, the application of

skill to solve a novel problem in a similar context; and far transfer,

the application of skill to solve novel problem presented in a different

context.

Furthermore, Perkins and Salomon (1992) suggest that positive transfer

in cases when learning supports novel problem solving, and negative

transfer occurs when prior learning inhibits performance on highly

correlated tasks, such as second or third-language learning.

Concepts of positive and negative transfer have a long history;

researchers in the early 20th century described the possibility that

"...habits or mental acts developed by a particular kind of training may

inhibit rather than facilitate other mental activities".

Finally, Schwarz, Bransford and Sears (2005) have proposed that

transferring knowledge into a situation may differ from transferring

knowledge out to a situation as a means to reconcile findings that

transfer may both be frequent and challenging to promote.

A significant and long research history has also attempted to

explicate the conditions under which transfer of learning might occur.

Early research by Ruger, for example, found that the "level of

attention", "attitudes", "method of attack" (or method for tackling a

problem), a "search for new points of view", "a careful testing of

hypothesis" and "generalization" were all valuable approaches for

promoting transfer.

To encourage transfer through teaching, Perkins and Salomon recommend

aligning ("hugging") instruction with practice and assessment, and

"bridging", or encouraging learners to reflect on past experiences or

make connections between prior knowledge and current content.

Factors affecting learning

External factors

- Heredity:

A classroom instructor can neither change nor increase heredity, but

the student can use and develop it. Some learners are rich in hereditary

endowment while others are poor. Each student is unique and has

different abilities. The native intelligence is different in

individuals. Heredity governs or conditions our ability to learn and the

rate of learning. The intelligent learners can establish and see

relationship very easily and more quickly.

- Status of students: Physical and home conditions also matter:

Certain problems like malnutrition i.e.; inadequate supply of nutrients

to the body, fatigue i.e.; tiredness, bodily weakness, and bad health

are great obstructers in learning. These are some of the physical

conditions by which a student can get affected. Home is a place where a

family lives. If the home conditions are not proper, the student is

affected seriously. Some of the home conditions are bad ventilation,

unhygienic living, bad light, etc. These affect the student and his or

her rate of learning.

- Physical environment: The design, quality, and setting of a learning space, such as a school or classroom, can each be critical to the success of a learning environment.

Size, configuration, comfort—fresh air, temperature, light, acoustics,

furniture—can all affect a student's learning. The tools used by both

instructors and students directly affect how information is conveyed,

from display and writing surfaces (blackboards, markerboards, tack

surfaces) to digital technologies. For example, if a room is too

crowded, stress levels rise, student attention is reduced, and furniture

arrangement is restricted. If furniture is incorrectly arranged, sight

lines to the instructor or instructional material is limited and the

ability to suit the learning or lesson style is restricted. Aesthetics

can also play a role, for if student morale suffers, so does motivation

to attend school.

Internal factors

There are several internal factors that affect learning. They are

- Goals or purposes: Each and everyone has a goal. A goal

should be set to each pupil according to the standard expected to him. A

goal is an aim or desired result. There are 2 types of goals called

immediate and distant goals. A goal that occurs or is done at once is

called an immediate goal, and distant goals are those that

take time to achieve. Immediate goals should be set before the young

learner and distant goals for older learners. Goals should be specific

and clear, so that learners understand.

- Motivational behavior: Motivation means to provide with a

motive. Motivation learners should be motivated so that they stimulate

themselves with interest. This behavior arouses and regulates the

student's internal energies.

- Interest: This is a quality that arouses a feeling. It

encourages a student to move over tasks further. During teaching, the

instructor must raise interests among students for the best learning.

Interest is an apparent (clearly seen or understood) behaviour.

- Attention: Attention means consideration. It is concentration

or focusing of consciousness upon one object or an idea. If effective

learning should take place attention is essential. Instructors must

secure the attention of the student.

- Drill or practice: This method includes repeating the tasks

"n" number of times like needs, phrases, principles, etc. This makes

learning more effective.

- Fatigue: Generally there are three types of fatigue, i.e.,

muscular, sensory, and mental. Muscular and sensory fatigues are bodily

fatigue. Mental fatigue is in the central nervous system. The remedy is

to change teaching methods, e.g., use audio-visual aids, etc.

- Aptitude:

Aptitude is natural ability. It is a condition in which an individuals

ability to acquire certain skills, knowledge through training.

- Attitude:

It is a way of thinking. The attitude of the student must be tested to

find out how much inclination he or she has for learning a subject or

topic.

- Emotional conditions: Emotions are physiological states of

being. Students who answer a question properly or give good results

should be praised. This encouragement increases their ability and helps

them produce better results. Certain attitudes, such as always finding

fault in a student's answer or provoking or embarrassing the student in

front of a class are counterproductive.

- Speed, Accuracy and retention: Speed is the rapidity of

movement. Retention is the act of retaining. These 3 elements depend

upon aptitude, attitude, interest, attention and motivation of the

students.

- Learning activities: Learning depends upon the activities and

experiences provided by the teacher, his concept of discipline, methods

of teaching and above all his overall personality.

- Testing: Various tests measure individual learner differences

at the heart of effective learning. Testing helps eliminate subjective

elements of measuring pupil differences and performances.

- Guidance: Everyone needs guidance in some part or some time

in life. Some need it constantly and some very rarely depending on the

students conditions. Small learners need more guidance. Guidance is an

advice to solve a problem. Guidance involves the art of helping boys and

girls in various aspects of academics, improving vocational aspects

like choosing careers and recreational aspects like choosing hobbies.

Guidance covers the whole gamut of learners problems- learning as well

as non- learning.

In animal evolution

Animals

gain knowledge in two ways. First is learning—in which an animal

gathers information about its environment and uses this information. For

example, if an animal eats something that hurts its stomach, it learns

not to eat that again. The second is innate knowledge that is

genetically inherited. An example of this is when a horse is born and

can immediately walk. The horse has not learned this behavior; it simply

knows how to do it. In some scenarios,

innate knowledge

is more beneficial than learned knowledge. However, in other scenarios

the opposite is true—animals must learn certain behaviors when it is

disadvantageous to have a specific innate behavior. In these situations,

learning

evolves in the species.

Costs and benefits of learned and innate knowledge

In

a changing environment, an animal must constantly gain new information

to survive. However, in a stable environment, this same individual needs

to gather the information it needs once, and then rely on it for the

rest of its life. Therefore, different scenarios better suit either

learning or innate knowledge.

Essentially, the cost of obtaining certain knowledge versus the benefit

of already having it determines whether an animal evolved to learn in a

given situation, or whether it innately knew the information. If the

cost of gaining the knowledge outweighs the benefit of having it, then

the animal does not evolve to learn in this scenario—but instead,

non-learning evolves. However, if the benefit of having certain

information outweighs the cost of obtaining it, then the animal is far

more likely to evolve to have to learn this information.

Non-learning is more likely to evolve in two scenarios. If an

environment is static and change does not or rarely occurs, then

learning is simply unnecessary. Because there is no need for learning in

this scenario—and because learning could prove disadvantageous due to

the time it took to learn the information—non-learning evolves. However,

if an environment is in a constant state of change, then learning is

disadvantageous. Anything learned is immediately irrelevant because of

the changing environment.

The learned information no longer applies. Essentially, the animal

would be just as successful if it took a guess as if it learned. In this

situation, non-learning evolves. In fact, a study of

Drosophila melanogaster

showed that learning can actually lead to a decrease in productivity,

possibly because egg-laying behaviors and decisions were impaired by

interference from the memories gained from the new learned materials or

because of the cost of energy in learning.

However, in environments where change occurs within an animal's

lifetime but is not constant, learning is more likely to evolve.

Learning is beneficial in these scenarios because an animal can

adapt

to the new situation, but can still apply the knowledge that it learns

for a somewhat extended period of time. Therefore, learning increases

the chances of success as opposed to guessing.

An example of this is seen in aquatic environments with landscapes

subject to change. In these environments, learning is favored because

the fish are predisposed to learn the specific spatial cues where they

live.

Machine learning

Robots can learn to cooperate.

Machine learning, a branch of

artificial intelligence,

concerns the construction and study of systems that can learn from

data. For example, a machine learning system could be trained on email

messages to learn to distinguish between spam and non-spam messages.