Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, or social outlook that emphasizes the moral worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and so value independence and self-reliance and advocate that interests of the individual should achieve precedence over the state or a social group, while opposing external interference upon one's own interests by society or institutions such as the government. Individualism is often defined in contrast to totalitarianism, collectivism, and more corporate social forms.

Individualism makes the individual its focus and so starts "with the fundamental premise that the human individual is of primary importance in the struggle for liberation." Classical liberalism, existentialism, and anarchism are examples of movements that take the human individual as a central unit of analysis. Individualism thus involves "the right of the individual to freedom and self-realization".

It has also been used as a term denoting "The quality of being an individual; individuality" related to possessing "An individual characteristic; a quirk." Individualism is thus also associated with artistic and bohemian interests and lifestyles where there is a tendency towards self-creation and experimentation as opposed to tradition or popular mass opinions and behaviors, as with humanist philosophical positions and ethics.

Individualism makes the individual its focus and so starts "with the fundamental premise that the human individual is of primary importance in the struggle for liberation." Classical liberalism, existentialism, and anarchism are examples of movements that take the human individual as a central unit of analysis. Individualism thus involves "the right of the individual to freedom and self-realization".

It has also been used as a term denoting "The quality of being an individual; individuality" related to possessing "An individual characteristic; a quirk." Individualism is thus also associated with artistic and bohemian interests and lifestyles where there is a tendency towards self-creation and experimentation as opposed to tradition or popular mass opinions and behaviors, as with humanist philosophical positions and ethics.

Etymology

The individual

An individual is a person or any specific object in a collection. In the 15th century and earlier, and also today within the fields of statistics and metaphysics, individual means "indivisible", typically describing any numerically singular thing, but sometimes meaning "a person." (q.v. "The problem of proper names"). From the 17th century on, individual indicates separateness, as in individualism. Individuality is the state or quality of being an individuated being; a person separated from everything with unique character by possessing his or her own needs, goals, and desires in comparison to other persons.Individuation principle

The principle of individuation , or principium individuationis, describes the manner in which a thing is identified as distinguished from other things. For Carl Jung, individuation is a process of transformation, whereby the personal and collective unconscious is brought into consciousness (by means of dreams, active imagination or free association to takexamples) to be assimilated into the whole personality. It is a completely natural process necessary for the integration of the psyche to take place. Jung considered individuation to be the central process of human development. In L'individuation psychique et collective, Gilbert Simondon developed a theory of individual and collective individuation in which the individual subject is considered as an effect of individuation rather than a cause. Thus, the individual atom is replaced by a never-ending ontological process of individuation. Individuation is an always incomplete process, always leaving a "pre-individual" left-over, itself making possible future individuations. The philosophy of Bernard Stiegler draws upon and modifies the work of Gilbert Simondon on individuation and also upon similar ideas in Friedrich Nietzsche and Sigmund Freud. For Stiegler "the I, as a psychic individual, can only be thought in relationship to we, which is a collective individual. The I is constituted in adopting a collective tradition, which it inherits and in which a plurality of I 's acknowledge each other's existence."Individualism and society

Individualism holds that a person taking part in society attempts to learn and discover what his or her own interests are on a personal basis, without a presumed following of the interests of a societal structure (an individualist need not be an egoist). The individualist does not follow one particular philosophy, rather creates an amalgamation of elements of many, based on personal interests in particular aspects that he/she finds of use. On a societal level, the individualist participates on a personally structured political and moral ground. Independent thinking and opinion is a common trait of an individualist. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, claims that his concept of "general will" in the "social contract" is not the simple collection of individual wills and that it furthers the interests of the individual (the constraint of law itself would be beneficial for the individual, as the lack of respect for the law necessarily entails, in Rousseau's eyes, a form of ignorance and submission to one's passions instead of the preferred autonomy of reason).Societies and groups can differ in the extent to which they are based upon predominantly "self-regarding" (individualistic, and/or self-interested) behaviors, rather than "other-regarding" (group-oriented, and group, or society-minded) behaviors. Ruth Benedict made a distinction, relevant in this context, between "guilt" societies (e.g., medieval Europe) with an "internal reference standard", and "shame" societies (e.g., Japan, "bringing shame upon one's ancestors") with an "external reference standard", where people look to their peers for feedback on whether an action is "acceptable" or not.

Individualism is often contrasted either with totalitarianism or with collectivism, but in fact, there is a spectrum of behaviors at the societal level ranging from highly individualistic societies through mixed societies to collectivist.

Methodological individualism

Methodological individualism is the view that phenomena can only be understood by examining how they result from the motivations and actions of individual agents. In economics, people's behavior is explained in terms of rational choices, as constrained by prices and incomes. The economist accepts individuals' preferences as givens. Becker and Stigler provide a forceful statement of this view:On the traditional view, an explanation of economic phenomena that reaches a difference in tastes between people or times is the terminus of the argument: the problem is abandoned at this point to whoever studies and explains tastes (psychologists? anthropologists? phrenologists? sociobiologists?). On our preferred interpretation, one never reaches this impasse: the economist continues to search for differences in prices or incomes to explain any differences or changes in behavior.

Competitive individualism

It is a form of individualism that arises from competitive systems. The function of the system is to maintain an inequality in the society and fields of human engagement. This pins the ups and downs of a person's life onto themselves by not acknowledging a range of factors like influence of socioeconomic class, race, gender, etc. It supports the privilege theories that affirms position of certain individuals higher in the hierarchy of ranks at the expense of others. For better individuality cooperation is considered to be a better remedy for personal growth.Political individualism

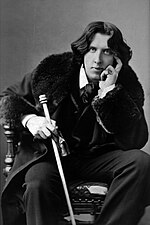

With the abolition of private property, then, we shall have true, beautiful, healthy Individualism. Nobody will waste his life in accumulating things, and the symbols for things. One will live. To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all. Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man under Socialism, 1891

Individualists are chiefly concerned with protecting individual autonomy against obligations imposed by social institutions (such as the state or religious morality). For L. Susan Brown "Liberalism and anarchism are two political philosophies that are fundamentally concerned with individual freedom yet differ from one another in very distinct ways. Anarchism shares with liberalism a radical commitment to individual freedom while rejecting liberalism's competitive property relations."

Civil libertarianism is a strain of political thought that supports civil liberties, or which emphasizes the supremacy of individual rights and personal freedoms over and against any kind of authority (such as a state, a corporation, social norms imposed through peer pressure, etc.). Civil libertarianism is not a complete ideology; rather, it is a collection of views on the specific issues of civil liberties and civil rights. Because of this, a civil libertarian outlook is compatible with many other political philosophies, and civil libertarianism is found on both the right and left in modern politics. For scholar Ellen Meiksins Wood "there are doctrines of individualism that are opposed to Lockean individualism ... and non-lockean individualism may encompass socialism".

British Historians Emily Robinson, Camilla Schofield, Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, and Natalie Thomlinson have argued that by the 1970s Britons were keen about defining and claiming their individual rights, identities and perspectives. They demanded greater personal autonomy and self-determination and less outside control. They angrily complained that the 'establishment' was withholding it. They argue this shift in concerns helped cause Thatcherism, and was incorporated into Thatcherism's appeal.

Liberalism

Liberalism (from the Latin liberalis, "of freedom; worthy of a free man, gentlemanlike, courteous, generous") is the belief in the importance of individual freedom. This belief is widely accepted in the United States, Europe, Australia and other Western nations, and was recognized as an important value by many Western philosophers throughout history, in particular since the Enlightenment. It is often rejected by collectivist, Islamic, or confucian societies in Asia or the Middle East (though Taoists were and are known to be individualists). The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote praising "the idea of a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed".For all intents and purposes, liberalism here refers to classical liberalism and should not be confused with modern liberalism in the United States,.

Liberalism has its roots in the Age of Enlightenment and rejects many foundational assumptions that dominated most earlier theories of government, such as the Divine Right of Kings, hereditary status, and established religion. John Locke is often credited with the philosophical foundations of classical liberalism. He wrote "no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions."

In the 17th century, liberal ideas began to influence governments in Europe, in nations such as The Netherlands, Switzerland, England and Poland, but they were strongly opposed, often by armed might, by those who favored absolute monarchy and established religion. In the 18th century, in America, the first modern liberal state was founded, without a monarch or a hereditary aristocracy. The American Declaration of Independence includes the words (which echo Locke) "all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to insure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed."

Liberalism comes in many forms. According to John N. Gray, the essence of liberalism is toleration of different beliefs and of different ideas as to what constitutes a good life.

Anarchism

Anarchism is a set of political philosophies that hold the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, or harmful, and often advocate stateless societies. While anti-statism is central, some argue that anarchism entails opposing authority or hierarchical organisation in the conduct of human relations, including, but not limited to, the state system.For influential Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta "All anarchists, whatever tendency they belong to, are individualists in some way or other. But the opposite is not true; not by any means. The individualists are thus divided into two distinct categories: one which claims the right to full development for all human individuality, their own and that of others; the other which only thinks about its own individuality and has absolutely no hesitation in sacrificing the individuality of others. The Tsar of all the Russias belongs to the latter category of individualists. We belong to the former."

Individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism refers to several traditions of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasize the individual and their will over any kinds of external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems. Individualist anarchism is not a single philosophy but refers to a group of individualistic philosophies that sometimes are in conflict.In 1793, William Godwin, who has often been cited as the first anarchist, wrote Political Justice, which some consider to be the first expression of anarchism. Godwin, a philosophical anarchist, from a rationalist and utilitarian basis opposed revolutionary action and saw a minimal state as a present "necessary evil" that would become increasingly irrelevant and powerless by the gradual spread of knowledge. Godwin advocated individualism, proposing that all cooperation in labour be eliminated on the premise that this would be most conducive with the general good.

An influential form of individualist anarchism, called "egoism," or egoist anarchism, was expounded by one of the earliest and best-known proponents of individualist anarchism, the German Max Stirner. Stirner's The Ego and Its Own, published in 1844, is a founding text of the philosophy. According to Stirner, the only limitation on the rights of the individual is their power to obtain what they desire, without regard for God, state, or morality. To Stirner, rights were spooks in the mind, and he held that society does not exist but "the individuals are its reality". Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw unions of egoists, non-systematic associations continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will, which Stirner proposed as a form of organization in place of the state. Egoist anarchists claim that egoism will foster genuine and spontaneous union between individuals. "Egoism" has inspired many interpretations of Stirner's philosophy. It was re-discovered and promoted by German philosophical anarchist and LGBT activist John Henry Mackay.

Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist, and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published. For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster "It is apparent...that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews...William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form.". Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) was an important early influence in individualist anarchist thought in the United States and Europe. Thoreau was an American author, poet, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor, historian, philosopher, and leading transcendentalist. He is best known for his books Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and his essay, Civil Disobedience, an argument for individual resistance to civil government in moral opposition to an unjust state. Later Benjamin Tucker fused Stirner's egoism with the economics of Warren and Proudhon in his eclectic influential publication Liberty.

From these early influences individualist anarchism in different countries attracted a small but diverse following of bohemian artists and intellectuals, free love and birth control advocates, individualist naturists nudists, freethought and anti-clerical activists as well as young anarchist outlaws in what came to be known as illegalism and individual reclamation. These authors and activists included Oscar Wilde, Emile Armand, Han Ryner, Henri Zisly, Renzo Novatore, Miguel Gimenez Igualada, Adolf Brand and Lev Chernyi among others. In his important essay The Soul of Man under Socialism from 1891 Oscar Wilde defended socialism as the way to guarantee individualism and so he saw that "With the abolition of private property, then, we shall have true, beautiful, healthy Individualism. Nobody will waste his life in accumulating things, and the symbols for things. One will live. To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all." For anarchist historian George Woodcock "Wilde's aim in The Soul of Man under Socialism is to seek the society most favorable to the artist ... for Wilde art is the supreme end, containing within itself enlightenment and regeneration, to which all else in society must be subordinated ... Wilde represents the anarchist as aesthete." Woodcock finds that "The most ambitious contribution to literary anarchism during the 1890s was undoubtedly Oscar Wilde The Soul of Man under Socialism" and finds that it is influenced mainly by the thought of William Godwin.

Philosophical individualism

Ethical egoism

Ethical egoism (also called simply egoism) is the normative ethical position that moral agents ought to do what is in their own self-interest. It differs from psychological egoism, which claims that people do only act in their self-interest. Ethical egoism also differs from rational egoism, which holds merely that it is rational to act in one's self-interest. However, these doctrines may occasionally be combined with ethical egoism.Ethical egoism contrasts with ethical altruism, which holds that moral agents have an obligation to help and serve others. Egoism and altruism both contrast with ethical utilitarianism, which holds that a moral agent should treat one's self (also known as the subject) with no higher regard than one has for others (as egoism does, by elevating self-interests and "the self" to a status not granted to others), but that one also should not (as altruism does) sacrifice one's own interests to help others' interests, so long as one's own interests (i.e. one's own desires or well-being) are substantially-equivalent to the others' interests and well-being. Egoism, utilitarianism, and altruism are all forms of consequentialism, but egoism and altruism contrast with utilitarianism, in that egoism and altruism are both agent-focused forms of consequentialism (i.e. subject-focused or subjective), but utilitarianism is called agent-neutral (i.e. objective and impartial) as it does not treat the subject's (i.e. the self's, i.e. the moral "agent's") own interests as being more or less important than if the same interests, desires, or well-being were anyone else's.

Ethical egoism does not, however, require moral agents to harm the interests and well-being of others when making moral deliberation; e.g. what is in an agent's self-interest may be incidentally detrimental, beneficial, or neutral in its effect on others. Individualism allows for others' interest and well-being to be disregarded or not, as long as what is chosen is efficacious in satisfying the self-interest of the agent. Nor does ethical egoism necessarily entail that, in pursuing self-interest, one ought always to do what one wants to do; e.g. in the long term, the fulfilment of short-term desires may prove detrimental to the self. Fleeting pleasance, then, takes a back seat to protracted eudaemonia. In the words of James Rachels, "Ethical egoism [...] endorses selfishness, but it doesn't endorse foolishness."

Caricature of Max Stirner taken from a sketch by Friedrich Engels. Egoist philosopher Max Stirner has been called a proto-existentialist philosopher while at the same time is a central theorist of individualist anarchism

Ethical egoism is sometimes the philosophical basis for support of libertarianism or individualist anarchism as in Max Stirner, although these can also be based on altruistic motivations. These are political positions based partly on a belief that individuals should not coercively prevent others from exercising freedom of action.

Egoist anarchism

Egoist anarchism is a school of anarchist thought that originated in the philosophy of Max Stirner, a nineteenth-century Hegelian philosopher whose "name appears with familiar regularity in historically orientated surveys of anarchist thought as one of the earliest and best-known exponents of individualist anarchism." According to Stirner, the only limitation on the rights of the individual is their power to obtain what they desire, without regard for God, state, or morality. Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw unions of egoists, non-systematic associations continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will, which Stirner proposed as a form of organisation in place of the state. Egoist anarchists argue that egoism will foster genuine and spontaneous union between individuals. "Egoism" has inspired many interpretations of Stirner's philosophy but within anarchism it has also gone beyond Stirner. It was re-discovered and promoted by German philosophical anarchist and LGBT activist John Henry Mackay. John Beverley Robinson wrote an essay called "Egoism" in which he states that "Modern egoism, as propounded by Stirner and Nietzsche, and expounded by Ibsen, Shaw and others, is all these; but it is more. It is the realization by the individual that they are an individual; that, as far as they are concerned, they are the only individual." Nietzsche (see Anarchism and Friedrich Nietzsche) and Stirner were frequently compared by French "literary anarchists" and anarchist interpretations of Nietzschean ideas appear to have also been influential in the United States. Anarchists who adhered to egoism include Benjamin Tucker, Émile Armand, John Beverley Robinson, Adolf Brand, Steven T. Byington, Renzo Novatore, James L. Walker, Enrico Arrigoni, Biofilo Panclasta, Jun Tsuji, André Arru and contemporary ones such as Hakim Bey, Bob Black and Wolfi Landstreicher.Existentialism

Existentialism is a term applied to the work of a number of 19th- and 20th-century philosophers who, despite profound doctrinal differences, generally held that the focus of philosophical thought should be to deal with the conditions of existence of the individual person and his or her emotions, actions, responsibilities, and thoughts. The early 19th century philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, posthumously regarded as the father of existentialism, maintained that the individual solely has the responsibilities of giving one's own life meaning and living that life passionately and sincerely, in spite of many existential obstacles and distractions including despair, angst, absurdity, alienation, and boredom.Subsequent existential philosophers retain the emphasis on the individual, but differ, in varying degrees, on how one achieves and what constitutes a fulfilling life, what obstacles must be overcome, and what external and internal factors are involved, including the potential consequences of the existence or non-existence of God. Many existentialists have also regarded traditional systematic or academic philosophy, in both style and content, as too abstract and remote from concrete human experience. Existentialism became fashionable after World War II as a way to reassert the importance of human individuality and freedom.

Freethought

Freethought holds that individuals should not accept ideas proposed as truth without recourse to knowledge and reason. Thus, freethinkers strive to build their opinions on the basis of facts, scientific inquiry, and logical principles, independent of any logical fallacies or intellectually limiting effects of authority, confirmation bias, cognitive bias, conventional wisdom, popular culture, prejudice, sectarianism, tradition, urban legend, and all other dogmas. Regarding religion, freethinkers hold that there is insufficient evidence to scientifically validate the existence of supernatural phenomena.Humanism

Humanism is a perspective common to a wide range of ethical stances that attaches importance to human dignity, concerns, and capabilities, particularly rationality. Although the word has many senses, its meaning comes into focus when contrasted to the supernatural or to appeals to authority. Since the 19th century, humanism has been associated with an anti-clericalism inherited from the 18th-century Enlightenment philosophes. 21st century Humanism tends to strongly endorse human rights, including reproductive rights, gender equality, social justice, and the separation of church and state. The term covers organized non-theistic religions, secular humanism, and a humanistic life stance.Hedonism

Philosophical hedonism is a meta-ethical theory of value which argues that pleasure is the only intrinsic good and pain is the only intrinsic bad. The basic idea behind hedonistic thought is that pleasure (an umbrella term for all inherently likable emotions) is the only thing that is good in and of itself or by its very nature. This implies evaluating the moral worth of character or behavior according to the extent that the pleasure it produces exceeds the pain it entails.Libertinism

A libertine is one devoid of most moral restraints, which are seen as unnecessary or undesirable, especially one who ignores or even spurns accepted morals and forms of behaviour sanctified by the larger society. Libertines place value on physical pleasures, meaning those experienced through the senses. As a philosophy, libertinism gained new-found adherents in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, particularly in France and Great Britain. Notable among these were John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester, and the Marquis de Sade. During the Baroque era in France, there existed a freethinking circle of philosophers and intellectuals who were collectively known as libertinage érudit and which included Gabriel Naudé, Élie Diodati and François de La Mothe Le Vayer. The critic Vivian de Sola Pinto linked John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester's libertinism to Hobbesian materialism.Objectivism

Objectivism is a system of philosophy created by philosopher and novelist Ayn Rand (1905–1982) that holds: reality exists independent of consciousness; human beings gain knowledge rationally from perception through the process of concept formation and inductive and deductive logic; the moral purpose of one's life is the pursuit of one's own happiness or rational self-interest. Rand thinks the only social system consistent with this morality is full respect for individual rights, embodied in pure laissez faire capitalism; and the role of art in human life is to transform man's widest metaphysical ideas, by selective reproduction of reality, into a physical form—a work of art—that he can comprehend and to which he can respond emotionally. Objectivism celebrates man as his own hero, "with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute."Philosophical anarchism

Benjamin Tucker, American individualist anarchist who focused on economics calling them "Anarchistic-Socialism" and adhering to the mutualist economics of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Josiah Warren

Philosophical anarchism is an anarchist school of thought which contends that the State lacks moral legitimacy and – in contrast to revolutionary anarchism – does not advocate violent revolution to eliminate it but advocate peaceful evolution to superate it. Though philosophical anarchism does not necessarily imply any action or desire for the elimination of the State, philosophical anarchists do not believe that they have an obligation or duty to obey the State, or conversely, that the State has a right to command.

Philosophical anarchism is a component especially of individualist anarchism. Philosophical anarchists of historical note include Mohandas Gandhi, William Godwin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Max Stirner, Benjamin Tucker, and Henry David Thoreau. Contemporary philosophical anarchists include A. John Simmons and Robert Paul Wolff.

Subjectivism

Subjectivism is a philosophical tenet that accords primacy to subjective experience as fundamental of all measure and law. In extreme forms like Solipsism, it may hold that the nature and existence of every object depends solely on someone's subjective awareness of it. For example, Wittgenstein wrote in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: "The subject doesn't belong to the world, but it is a limit of the world" (proposition 5.632). Metaphysical subjectivism is the theory that reality is what we perceive to be real, and that there is no underlying true reality that exists independently of perception. One can also hold that it is consciousness rather than perception that is reality (subjective idealism). In probability, a subjectivism stands for the belief that probabilities are simply degrees-of-belief by rational agents in a certain proposition, and which have no objective reality in and of themselves.Ethical subjectivism stands in opposition to moral realism, which claims that moral propositions refer to objective facts, independent of human opinion; to error theory, which denies that any moral propositions are true in any sense; and to non-cognitivism, which denies that moral sentences express propositions at all. The most common forms of ethical subjectivism are also forms of moral relativism, with moral standards held to be relative to each culture or society (c.f. cultural relativism), or even to every individual. The latter view, as put forward by Protagoras, holds that there are as many distinct scales of good and evil as there are subjects in the world. Moral subjectivism is that species of moral relativism that relativizes moral value to the individual subject.

Horst Matthai Quelle was a Spanish language German anarchist philosopher influenced by Max Stirner. He argued that since the individual gives form to the world, he is those objects, the others and the whole universe. One of his main views was a "theory of infinite worlds" which for him was developed by pre-socratic philosophers.

Solipsism

Solipsism is the philosophical idea that only one's own mind is sure to exist. The term comes from Latin solus (alone) and ipse (self). Solipsism as an epistemological position holds that knowledge of anything outside one's own mind is unsure. The external world and other minds cannot be known, and might not exist outside the mind. As a metaphysical position, solipsism goes further to the conclusion that the world and other minds do not exist. As such it is the only epistemological position that, by its own postulate, is both irrefutable and yet indefensible in the same manner. Although the number of individuals sincerely espousing solipsism has been small, it is not uncommon for one philosopher to accuse another's arguments of entailing solipsism as an unwanted consequence, in a kind of reductio ad absurdum. In the history of philosophy, solipsism has served as a skeptical hypothesis.Economic individualism

The doctrine of economic individualism holds that each individual should be allowed autonomy in making his or her own economic decisions as opposed to those decisions being made by the state, the community, the corporation etc. for him or her.Liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political ideology that developed in the 19th century in England, Western Europe, and the Americas. It followed earlier forms of liberalism in its commitment to personal freedom and popular government, but differed from earlier forms of liberalism in its commitment to free markets and classical economics. Notable classical liberals in the 19th century include Jean-Baptiste Say, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo. Classical liberalism was revived in the 20th century by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, and further developed by Milton Friedman, Robert Nozick, Loren Lomasky, and Jan Narveson. The phrase classical liberalism is also sometimes used to refer to all forms of liberalism before the 20th century.Individualist anarchism and economics

Influential French individualist anarchist Emile Armand

In regards to economic questions within individualist anarchism there are adherents to mutualism (Pierre Joseph Proudhon, Emile Armand, early Benjamin Tucker); natural rights positions (early Benjamin Tucker, Lysander Spooner, Josiah Warren); and egoistic disrespect for "ghosts" such as private property and markets (Max Stirner, John Henry Mackay, Lev Chernyi, later Benjamin Tucker, Renzo Novatore, illegalism). Contemporary individualist anarchist Kevin Carson characterizes American individualist anarchism saying that "Unlike the rest of the socialist movement, the individualist anarchists believed that the natural wage of labor in a free market was its product, and that economic exploitation could only take place when capitalists and landlords harnessed the power of the state in their interests. Thus, individualist anarchism was an alternative both to the increasing statism of the mainstream socialist movement, and to a classical liberal movement that was moving toward a mere apologetic for the power of big business."

Mutualism

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought which can be traced to the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who envisioned a society where each person might possess a means of production, either individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent amounts of labor in the free market. Integral to the scheme was the establishment of a mutual-credit bank which would lend to producers at a minimal interest rate only high enough to cover the costs of administration. Mutualism is based on a labor theory of value which holds that when labor or its product is sold, in exchange, it ought to receive goods or services embodying "the amount of labor necessary to produce an article of exactly similar and equal utility". Receiving anything less would be considered exploitation, theft of labor, or usury.Libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism (sometimes dubbed socialist libertarianism, or left-libertarianism) is a group of anti-authoritarian political philosophies inside the socialist movement that rejects socialism as centralized state ownership and control of the economy, as well as the state itself. It criticizes wage labour relationships within the workplace. Instead, it emphasizes workers' self-management of the workplace and decentralized structures of political organization. It asserts that a society based on freedom and justice can be achieved through abolishing authoritarian institutions that control certain means of production and subordinate the majority to an owning class or political and economic elite. Libertarian socialists advocate for decentralized structures based on direct democracy and federal or confederal associations such as libertarian municipalism, citizens' assemblies, trade unions, and workers' councils. All of this is generally done within a general call for libertarian and voluntary human relationships through the identification, criticism, and practical dismantling of illegitimate authority in all aspects of human life. As such libertarian socialism, within the larger socialist movement, seeks to distinguish itself both from Leninism/Bolshevism and from social democracy.Past and present political philosophies and movements commonly described as libertarian socialist include anarchism (especially anarchist communism, anarchist collectivism, anarcho-syndicalism, and mutualism) as well as autonomism, communalism, participism, guild socialism, revolutionary syndicalism, and libertarian Marxist philosophies such as council communism and Luxemburgism; as well as some versions of "utopian socialism" and individualist anarchism.

Left-libertarianism

Left-libertarianism (or left-wing libertarianism) names several related but distinct approaches to politics, society, culture, and political and social theory, which stress both individual freedom and social justice. Unlike right-libertarians, they believe that neither claiming nor mixing one's labor with natural resources is enough to generate full private property rights, and maintain that natural resources (land, oil, gold, trees) ought to be held in some egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively. Those left-libertarians who support private property do so under the condition that recompense is offered to the local community.Left-libertarianism can refer generally to these related and overlapping schools of thought:

- Anti-authoritarian varieties of left-wing politics and, in particular, the socialist movement, usually known as libertarian socialism;

- Geolibertarianism: a synthesis of libertarianism and geoism;

- The Steiner–Vallentyne school, whose proponents draw conclusions from classical liberal or market liberal premises;

- Left-wing market anarchism, which stresses the socially transformative potential of non-aggression and anticapitalist, freed markets.

Right-libertarianism

Right-libertarianism or right libertarianism is a phrase used by some to describe either non-collectivist forms of libertarianism or a variety of different libertarian views some label "right" of mainstream libertarianism including "libertarian conservatism".Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy calls it "right libertarianism" but states: "Libertarianism is often thought of as 'right-wing' doctrine. This, however, is mistaken for at least two reasons. First, on social—rather than economic—issues, libertarianism tends to be 'left-wing'. It opposes laws that restrict consensual and private sexual relationships between adults (e.g., gay sex, non-marital sex, and deviant sex), laws that restrict drug use, laws that impose religious views or practices on individuals, and compulsory military service. Second, in addition to the better-known version of libertarianism—right-libertarianism—there is also a version known as 'left-libertarianism'. Both endorse full self-ownership, but they differ with respect to the powers agents have to appropriate unappropriated natural resources (land, air, water, etc.)."

As creative independent lifestyle

The anarchist writer and bohemian Oscar Wilde wrote in his famous essay The Soul of Man under Socialism that "Art is individualism, and individualism is a disturbing and disintegrating force. There lies its immense value. For what it seeks is to disturb monotony of type, slavery of custom, tyranny of habit, and the reduction of man to the level of a machine." For anarchist historian George Woodcock "Wilde's aim in The Soul of Man under Socialism is to seek the society most favorable to the artist...for Wilde art is the supreme end, containing within itself enlightenment and regeneration, to which all else in society must be subordinated...Wilde represents the anarchist as aesthete." The word individualism in this way has been used to denote a personality with a strong tendency towards self-creation and experimentation as opposed to tradition or popular mass opinions and behaviors.

Anarchist writer Murray Bookchin describes a lot of individualist anarchists as people who "expressed their opposition in uniquely personal forms, especially in fiery tracts, outrageous behavior, and aberrant lifestyles in the cultural ghettos of fin de siècle New York, Paris, and London. As a credo, individualist anarchism remained largely a bohemian lifestyle, most conspicuous in its demands for sexual freedom ('free love') and enamored of innovations in art, behavior, and clothing."

In relation to this view of individuality, French Individualist anarchist Emile Armand advocates egoistical denial of social conventions and dogmas to live in accord to one's own ways and desires in daily life since he emphasized anarchism as a way of life and practice. In this way he opines "So the anarchist individualist tends to reproduce himself, to perpetuate his spirit in other individuals who will share his views and who will make it possible for a state of affairs to be established from which authoritarianism has been banished. It is this desire, this will, not only to live, but also to reproduce oneself, which we shall call "activity".

In the book Imperfect garden : the legacy of humanism, humanist philosopher Tzvetan Todorov identifies individualism as an important current of socio-political thought within modernity and as examples of it he mentions Michel de Montaigne, François de La Rochefoucauld, Marquis de Sade, and Charles Baudelaire. In La Rochefoucauld, he identifies a tendency similar to stoicism in which "the honest person works his being in the manner of a sculptor who searches the liberation of the forms which are inside a block of marble, to extract the truth of that matter." In Baudelaire he finds the dandy trait in which one searches to cultivate "the idea of beauty within oneself, of satisfying one's passions of feeling and thinking."

The Russian-American poet Joseph Brodsky once wrote that "The surest defense against Evil is extreme individualism, originality of thinking, whimsicality, even—if you will—eccentricity. That is, something that can't be feigned, faked, imitated; something even a seasoned imposter couldn't be happy with." Ralph Waldo Emerson famously declared, "Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist"—a point of view developed at length in both the life and work of Henry David Thoreau. Equally memorable and influential on Walt Whitman is Emerson's idea that "a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines." Emerson opposes on principle the reliance on civil and religious social structures precisely because through them the individual approaches the divine second-hand, mediated by the once original experience of a genius from another age. "An institution," he explains, "is the lengthened shadow of one man." To achieve this original relation one must "Insist on one's self; never imitate" for if the relationship is secondary the connection is lost.