Maya, the mirror of illusions, a painting by the American artist Arthur Bowen Davies (1910)

Maya (/ˈmɑːjə/; Devanagari: माया, IAST: māyā), literally "illusion" or "magic", has multiple meanings in Indian philosophies depending on the context. In ancient Vedic literature, Māyā literally implies extraordinary power and wisdom. In later Vedic texts and modern literature dedicated to Indian traditions, Māyā connotes a "magic show, an illusion where things appear to be present but are not what they seem". Māyā is also a spiritual concept connoting "that which exists, but is constantly changing and thus is spiritually unreal", and the "power or the principle that conceals the true character of spiritual reality".

In Buddhism, Maya is the name of Gautama Buddha's mother. In Hinduism, Maya is also an epithet for goddess, and the name of a manifestation of Lakshmi, the goddess of "wealth, prosperity and love". Maya is also a name for girls.

Etymology and terminology

Māyā (Sanskrit: माया) is a word with unclear etymology, probably comes from the root mā which means "to measure".According to Monier Williams, māyā meant "wisdom and extraordinary power" in an earlier older language, but from the Vedic period onwards, the word came to mean "illusion, unreality, deception, fraud, trick, sorcery, witchcraft and magic". However, P. D. Shastri states that the Monier Williams' list is a "loose definition, misleading generalization", and not accurate in interpreting ancient Vedic and medieval era Sanskrit texts; instead, he suggests a more accurate meaning of māyā is "appearance, not mere illusion".

According to William Mahony, the root of the word may be man- or "to think", implying the role of imagination in the creation of the world. In early Vedic usage, the term implies, states Mahony, "the wondrous and mysterious power to turn an idea into a physical reality".

Franklin Southworth states the word's origin is uncertain, and other possible roots of māyā include may- meaning mystify, confuse, intoxicate, delude, as well as māy- which means "disappear, be lost".

Jan Gonda considers the word related to mā, which means "mother", as do Tracy Pintchman and Adrian Snodgrass, serving as an epithet for goddesses such as Lakshmi. Maya here implies art, is the maker’s power, writes Zimmer, "a mother in all three worlds", a creatrix, her magic is the activity in the Will-spirit.

A similar word is also found in the Avestan māyā with the meaning of "magic power".

Hinduism

Literature

The Vedas

Words related to and containing Māyā, such as Mayava, occur many times in the Vedas. These words have various meanings, with interpretations that are contested, and some are names of deities that do not appear in texts of 1st millennium BCE and later. The use of word Māyā in Rig veda, in the later era context of "magic, illusion, power", occurs in many hymns. One titled Māyā-bheda (मायाभेद:, Discerning Illusion) includes hymns 10.177.1 through 10.177.3, as the battle unfolds between the good and the evil, as follows,The above Maya-bheda hymn discerns, using symbolic language, a contrast between mind influenced by light (sun) and magic (illusion of Asura). The hymn is a call to discern one's enemies, perceive artifice, and distinguish, using one's mind, between that which is perceived and that which is unperceived. Rig veda does not connote the word Māyā as always good or always bad, it is simply a form of technique, mental power and means. Rig veda uses the word in two contexts, implying that there are two kinds of Māyā: divine Māyā and undivine Māyā, the former being the foundation of truth, the latter of falsehood.पतंगमक्तमसुरस्य मायया हृदा पश्यन्ति मनसा विपश्चितः ।

समुद्रे अन्तः कवयो वि चक्षते मरीचीनां पदमिच्छन्ति वेधसः ॥१॥

पतंगो वाचं मनसा बिभर्ति तां गन्धर्वोऽवदद्गर्भे अन्तः ।

तां द्योतमानां स्वर्यं मनीषामृतस्य पदे कवयो नि पान्ति ॥२॥

अपश्यं गोपामनिपद्यमानमा च परा च पथिभिश्चरन्तम् ।

स सध्रीचीः स विषूचीर्वसान आ वरीवर्ति भुवनेष्वन्तः ॥३॥

The wise behold with their mind in their heart the Sun, made manifest by the illusion of the Asura;

The sages look into the solar orb, the ordainers desire the region of his rays.

The Sun bears the word in his mind; the Gandharva has spoken it within the wombs;

sages cherish it in the place of sacrifice, brilliant, heavenly, ruling the mind.

I beheld the protector, never descending, going by his paths to the east and the west;

clothing the quarters of the heaven and the intermediate spaces. He constantly revolves in the midst of the worlds.

— Rig veda X.177.1-3, Translated by Laurie Patton

Elsewhere in Vedic mythology, Indra uses Maya to conquer Vritra. Varuna's supernatural power is called Maya. Māyā, in such examples, connotes powerful magic, which both devas (gods) and asuras (demons) use against each other. In the Yajurveda, māyā is an unfathomable plan. In the Aitareya Brahmana Maya is also referred to as Dirghajihvi, hostile to gods and sacrifices. The hymns in Book 8, Chapter 10 of Atharvaveda describe the primordial woman Virāj (विराज्, chief queen) and how she willingly gave the knowledge of food, plants, agriculture, husbandry, water, prayer, knowledge, strength, inspiration, concealment, charm, virtue, vice to gods, demons, men and living creatures, despite all of them making her life miserable. In hymns of 8.10.22, Virāj is used by Asuras (demons) who call her as Māyā, as follows,

The contextual meaning of Maya in Atharvaveda is "power of creation", not illusion. Gonda suggests the central meaning of Maya in Vedic literature is, "wisdom and power enabling its possessor, or being able itself, to create, devise, contrive, effect, or do something". Maya stands for anything that has real, material form, human or non-human, but that does not reveal the hidden principles and implicit knowledge that creates it. An illustrative example of this in Rig veda VII.104.24 and Atharva veda VIII.4.24 where Indra is invoked against the Maya of sorcerers appearing in the illusory form – like a fata morgana – of animals to trick a person.She rose. The Asuras saw her. They called her. Their cry was, "Come, O Māyā, come thou hither" !!

Her cow was Virochana Prahradi. Her milking vessel was a pan of iron.

Dvimurdha Artvya milked this Māyā.

The Asuras depend for life on Māyā for their sustenance.

One who knows this, becomes a fit supporter [of gods].

— Atharva veda VIII.10.22

The Upanishads

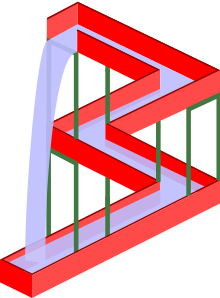

M. C. Escher paintings such as the Waterfall – redrawn in this sketch – demonstrates the Hindu concept of Maya, states Jeffrey Brodd. The impression of water-world the sketch gives, in reality is not what it seems.

The Upanishads describe the universe, and the human experience, as an interplay of Purusha (the eternal, unchanging principles, consciousness) and Prakṛti (the temporary, changing material world, nature). The former manifests itself as Ātman (Soul, Self), and the latter as Māyā. The Upanishads refer to the knowledge of Atman as "true knowledge" (Vidya), and the knowledge of Maya as "not true knowledge" (Avidya, Nescience, lack of awareness, lack of true knowledge). Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, states Ben-Ami Scharfstein, describes Maya as "the tendency to imagine something where it does not exist, for example, atman with the body". To the Upanishads, knowledge includes empirical knowledge and spiritual knowledge, complete knowing necessarily includes understanding the hidden principles that work, the realization of the soul of things.

Hendrick Vroom explains, "The term Maya has been translated as 'illusion,' but then it does not concern normal illusion. Here 'illusion' does not mean that the world is not real and simply a figment of the human imagination. Maya means that the world is not as it seems; the world that one experiences is misleading as far as its true nature is concerned." Lynn Foulston states, "The world is both real and unreal because it exists but is 'not what it appears to be'." According to Wendy Doniger, "to say that the universe is an illusion (māyā) is not to say that it is unreal; it is to say, instead, that it is not what it seems to be, that it is something constantly being made. Māyā not only deceives people about the things they think they know; more basically, it limits their knowledge."

Māyā pre-exists and co-exists with Brahman – the Ultimate Principle, Consciousness. Maya is perceived reality, one that does not reveal the hidden principles, the true reality. Maya is unconscious, Atman is conscious. Maya is the literal, Brahman is the figurative Upādāna – the principle, the cause. Maya is born, changes, evolves, dies with time, from circumstances, due to invisible principles of nature, state the Upanishads. Atman-Brahman is eternal, unchanging, invisible principle, unaffected absolute and resplendent consciousness. Maya concept in the Upanishads, states Archibald Gough, is "the indifferent aggregate of all the possibilities of emanatory or derived existences, pre-existing with Brahman", just like the possibility of a future tree pre-exists in the seed of the tree.

The concept of Maya appears in numerous Upanishads. The verses 4.9 to 4.10 of Svetasvatara Upanishad, is the oldest explicit occurrence of the idea that Brahman (Supreme Soul) is the hidden reality, nature is magic, Brahman is the magician, human beings are infatuated with the magic and thus they create bondage to illusions and delusions, and for freedom and liberation one must seek true insights and correct knowledge of the principles behind the hidden magic. Gaudapada in his Karika on Mandukya Upanishad explains the interplay of Atman and Maya as follows,

Sarvasara Upanishad refers to two concepts: Mithya and Maya. It defines Mithya as illusion and calls it one of three kinds of substances, along with Sat (Be-ness, True) and Asat (not-Be-ness, False). Maya, Sarvasara Upanishad defines as all what is not Atman. Maya has no beginning, but has an end. Maya, declares Sarvasara, is anything that can be studied and subjected to proof and disproof, anything with Guṇas. In the human search for Self-knowledge, Maya is that which obscures, confuses and distracts an individual.The Soul is imagined first, then the particularity of objects,

External and internal, as one knows so one remembers.

As a rope, not perceived distinctly in dark, is erroneously imagined,

As snake, as a streak of water, so is the Soul (Atman) erroneously imagined.

As when the rope is distinctly perceived, and the erroneous imagination withdrawn,

Only the rope remains, without a second, so when distinctly perceived, the Atman.

When he as Pranas (living beings), as all the diverse objects appears to us,

Then it is all mere Maya, with which the Brahman (Supreme Soul) deceives himself.

— Gaudapada, Māṇḍukya Kārikā 2.16-19

The Puranas and Tamil texts

Markandeya sees Vishnu as an infant on a fig leaf in the deluge.

In Puranas and Vaishnava theology, māyā is described as one of the nine shaktis of Vishnu. Māyā became associated with sleep; and Vishnu's māyā is sleep which envelopes the world when he awakes to destroy evil. Vishnu, like Indra, is the master of māyā; and māyā envelopes Vishnu's body. The Bhagavata Purana narrates that the sage Markandeya requests Vishnu to experience his māyā. Vishnu appears as an infant floating on a fig leaf in a deluge and then swallows the sage, the sole survivor of the cosmic flood. The sage sees various worlds of the universe, gods etc. and his own hermitage in the infant's belly. Then the infant breathes out the sage, who tries to embrace the infant, but everything disappears and the sage realizes that he was in his hermitage the whole time and was given a flavor of Vishnu's māyā. The magic creative power, Māyā was always a monopoly of the central Solar God; and was also associated with the early solar prototype of Vishnu in the early Aditya phase.

In Sangam period Tamil literature, Krishna is found as māyon; with other attributed names are such as Mal, Tirumal, Perumal and Mayavan. In the Tamil classics, Durga is referred to by the feminine form of the word, viz., māyol; wherein she is endowed with unlimited creative energy and the great powers of Vishnu, and is hence Vishnu-Maya.

Maya, to Shaiva Siddhanta sub-school of Hinduism, states Hilko Schomerus, is reality and truly existent, and one that exists to "provide Souls with Bhuvana (a world), Bhoga (objects of enjoyment), Tanu (a body) and Karana (organs)".

Schools of Hinduism

Need to understand Māyā

The various schools of Hinduism, particularly those based on naturalism (Vaiśeṣika), rationalism (Samkhya) or ritualism (Mimamsa), questioned and debated what is Maya, and the need to understand Maya. The Vedanta and Yoga schools explained that complete realization of knowledge requires both the understanding of ignorance, doubts and errors, as well as the understanding of invisible principles, incorporeal and the eternal truths. In matters of Self-knowledge, stated Shankara in his commentary on Taittiriya Upanishad, one is faced with the question, "Who is it that is trying to know, and how does he attain Brahman?" It is absurd, states Shankara, to speak of one becoming himself; because "Thou Art That" already. Realizing and removing ignorance is a necessary step, and this can only come from understanding Maya and then looking beyond it.The need to understand Maya is like the metaphorical need for road. Only when the country to be reached is distant, states Shankara, that a road must be pointed out. It is a meaningless contradiction to assert, "I am right now in my village, but I need a road to reach my village." It is the confusion, ignorance and illusions that need to be repealed. It is only when the knower sees nothing else but his Self that he can be fearless and permanent. Vivekananda explains the need to understand Maya as follows (abridged),

The Vedas cannot show you Brahman, you are That already. They can only help to take away the veil that hides truth from our eyes. The cessation of ignorance can only come when I know that God and I are one; in other words, identify yourself with Atman, not with human limitations. The idea that we are bound is only an illusion [Maya]. Freedom is inseparable from the nature of the Atman. This is ever pure, ever perfect, ever unchangeable.The text Yoga Vasistha explains the need to understand Maya as follows,

— Adi Shankara's commentary on Fourth Vyasa Sutra, Swami Vivekananda

Just as when the dirt is removed, the real substance is made manifest; just as when the darkness of the night is dispelled, the objects that were shrouded by the darkness are clearly seen, when ignorance [Maya] is dispelled, truth is realized.

— Vashistha, Yoga Vasiṣṭha

Samkhya school

The early works of Samkhya, the rationalist school of Hinduism, do not identify or directly mention the Maya doctrine. The discussion of Maya theory, calling it into question, appears after the theory gains ground in Vedanta school of Hinduism. Vācaspati Miśra's commentary on the Samkhyakarika, for example, questions the Maya doctrine saying "It is not possible to say that the notion of the phenomenal world being real is false, for there is no evidence to contradict it". Samkhya school steadfastly retained its duality concept of Prakrti and Purusha, both real and distinct, with some texts equating Prakrti to be Maya that is "not illusion, but real", with three Guṇas in different proportions whose changing state of equilibrium defines the perceived reality.James Ballantyne, in 1885, commented on Kapila's Sánkhya aphorism 5.72 which he translated as, "everything except nature and soul is uneternal". According to Ballantyne, this aphorism states that the mind, ether, etc. in a state of cause (not developed into a product) are called Nature and not Intellect. He adds, that scriptural texts such as Shvetashvatara Upanishad to be stating "He should know Illusion to be Nature and him in whom is Illusion to be the great Lord and the world to be pervaded by portions of him'; since Soul and Nature are also made up of parts, they must be uneternal". However, acknowledges Ballantyne, Edward Gough translates the same verse in Shvetashvatara Upanishad differently, 'Let the sage know that Prakriti is Maya and that Mahesvara is the Mayin, or arch-illusionist. All this shifting world is filled with portions of him'. In continuation of the Samkhya and Upanishadic view, in the Bhagavata philosophy, Maya has been described as 'that which appears even when there is no object like silver in a shell and which does not appear in the atman'; with maya described as the power that creates, maintains and destroys the universe.

Nyaya school

The realism-driven Nyaya school of Hinduism denied that either the world (Prakrti) or the soul (Purusa) are an illusion. Naiyayikas developed theories of illusion, typically using the term Mithya, and stated that illusion is simply flawed cognition, incomplete cognition or the absence of cognition. There is no deception in the reality of Prakrti or Pradhana (creative principle of matter/nature) or Purusa, only confusion or lack of comprehension or lack of cognitive effort, according to Nyaya scholars. To them, illusion has a cause, that rules of reason and proper Pramanas (epistemology) can uncover.Illusion, stated Naiyayikas, involves the projection into current cognition of predicated content from memory (a form of rushing to interpret, judge, conclude). This "projection illusion" is misplaced, and stereotypes something to be what it is not. The insights on theory of illusion by Nyaya scholars were later adopted and applied by Advaita Vedanta scholars.

Yoga school

Maya in Yoga school is the manifested world and implies divine force. Yoga and Maya are two sides of the same coin, states Zimmer, because what is referred to as Maya by living beings who are enveloped by it, is Yoga for the Brahman (Universal Principle, Supreme Soul) whose yogic perfection creates the Maya. Maya is neither illusion nor denial of perceived reality to the Yoga scholars, rather Yoga is a means to perfect the "creative discipline of mind" and "body-mind force" to transform Maya.The concept of Yoga as power to create Maya has been adopted as a compound word Yogamaya (योगमाया) by the theistic sub-schools of Hinduism. It occurs in various mythologies of the Puranas; for example, Shiva uses his yogamāyā to transform Markendeya's heart in Bhagavata Purana's chapter 12.10, while Krishna counsels Arjuna about yogamāyā in hymn 7.25 of Bhagavad Gita.

Vedanta school

Maya is a prominent and commonly referred to concept in Vedanta philosophies. Maya is often translated as "illusion", in the sense of "appearance". Human mind constructs a subjective experience, states Vedanta school, which leads to the peril of misunderstanding Maya as well as interpreting Maya as the only and final reality. Vedantins assert the "perceived world including people are not what they appear to be". There are invisible principles and laws at work, true invisible nature in others and objects, and invisible soul that one never perceives directly, but this invisible reality of Self and Soul exists, assert Vedanta scholars. Māyā is that which manifests, perpetuates a sense of false duality (or divisional plurality). This manifestation is real, but it obfuscates and eludes the hidden principles and true nature of reality. Vedanta school holds that liberation is the unfettered realization and understanding of these invisible principles – the Self, that the Self (Soul) in oneself is same as the Self in another and the Self in everything (Brahman). The difference within various sub-schools of Vedanta is the relationship between individual soul and cosmic soul (Brahman). Non-theistic Advaita sub-school holds that both are One, everyone is thus deeply connected Oneness, there is God in everyone and everything; while theistic Dvaita and other sub-schools hold that individual souls and God's soul are distinct and each person can at best love God constantly to get one's soul infinitely close to His Soul.Advaita Vedanta

In Advaita Vedanta philosophy, there are two realities: Vyavaharika (empirical reality) and Paramarthika (absolute, spiritual reality). Māyā is the empirical reality that entangles consciousness. Māyā has the power to create a bondage to the empirical world, preventing the unveiling of the true, unitary Self—the Cosmic Spirit also known as Brahman. The theory of māyā was developed by the ninth-century Advaita Hindu philosopher Adi Shankara. However, competing theistic Dvaita scholars contested Shankara's theory, and stated that Shankara did not offer a theory of the relationship between Brahman and Māyā. A later Advaita scholar Prakasatman addressed this, by explaining, "Maya and Brahman together constitute the entire universe, just like two kinds of interwoven threads create a fabric. Maya is the manifestation of the world, whereas Brahman, which supports Maya, is the cause of the world."

Māyā is a fact in that it is the appearance of phenomena. Since Brahman is the sole metaphysical truth, Māyā is true in epistemological and empirical sense; however, Māyā is not the metaphysical and spiritual truth. The spiritual truth is the truth forever, while what is empirical truth is only true for now. Since Māyā is the perceived material world, it is true in perception context, but is "untrue" in spiritual context of Brahman. Māyā is not false, it only clouds the inner Self and principles that are real. True Reality includes both Vyavaharika (empirical) and Paramarthika (spiritual), the Māyā and the Brahman. The goal of spiritual enlightenment, state Advaitins, is to realize Brahman, realize the fearless, resplendent Oneness.

Vivekananda said: "When the Hindu says the world is Maya, at once people get the idea that the world is an illusion. This interpretation has some basis, as coming through the Buddhistic philosophers, because there was one section of philosophers who did not believe in the external world at all. But the Maya of the Vedanta, in its last developed form, is neither Idealism nor Realism, nor is it a theory. It is a simple statement of facts — what we are and what we see around us."

Buddhism

The Early Buddhist Texts contain some references to illusion, the most well known of which is the Pheṇapiṇḍūpama Sutta in Pali (and with a Chinese Agama parallel at SĀ 265) which states:Suppose, monks, that a magician (māyākāro) or a magician’s apprentice (māyākārantevāsī) would display a magical illusion (māyaṃ) at a crossroads. A man with good sight would inspect it, ponder, and carefully investigate it, and it would appear to him to be void (rittaka), hollow (tucchaka), coreless (asāraka). For what core (sāro) could there be in a magical illusion (māyāya)? So too, monks, whatever kind of cognition there is, whether past, future, or present, internal or external, gross or subtle, inferior or superior, far or near: a monk inspects it, ponders it, and carefully investigates it, and it would appear to him to be void (rittaka), hollow (tucchaka), coreless (asāraka). For what core (sāro) could there be in cognition?One sutra in the Āgama collection known as "Mahāsūtras" of the (Mūla)Sarvāstivādin tradition entitled the Māyājāla (Net of Illusion) deals especially with the theme of Maya. This sutra only survives in Tibetan translation and compares the five aggregates with further metaphors for illusion, including: an echo, a reflection in a mirror, a mirage, sense pleasures in a dream and a madman wandering naked.

These texts give the impression that māyā refers to the insubstantial and essence-less nature of things as well as their deceptive, false and vain character.

Later texts such as the Lalitavistara also contain references to illusion:

- "Complexes have no inner might, are empty in themselves; Rather like the stem of the plantain tree, when one reflects on them, Like an illusion (māyopama) which deludes the mind (citta), Like an empty fist with which a child is teased."

Theravada

In Theravada Buddhism 'Māyā' is the name of the mother of the Buddha as well as a metaphor for the consciousness aggregate (viññana). The Theravada monk Bhikkhu Bodhi considers the Pali Pheṇapiṇḍūpama Sutta “one of the most radical discourses on the empty nature of conditioned phenomena.” Bodhi also cites the Pali commentary on this sutra, the Sāratthappakāsinī (Spk), which states:Cognition is like a magical illusion (māyā) in the sense that it is insubstantial and cannot be grasped. Cognition is even more transient and fleeting than a magical illusion. For it gives the impression that a person comes and goes, stands and sits, with the same mind, but the mind is different in each of these activities. Cognition deceives the multitude like a magical illusion (māyā).Likewise, Bhikkhu Katukurunde Nyanananda Thera has written an exposition of the Kàlakàràma Sutta which features the image of a magical illusion as its central metaphor.

Sarvastivada

The Nyānānusāra Śāstra, a Vaibhāṣika response to Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakosha cites the Māyājāla sutra and explains:“Seeing an illusory object (māyā)”: Although what one apprehends is unreal, nothing more than an illusory sign. If one does not admit this much, then an illusory sign should be non-existent. What is an illusory sign? It is the result of illusion magic. Just as one with higher gnosis can magically create forms, likewise this illusory sign does actually have manifestation and shape. Being produced by illusion magic, it acts as the object of vision. That object which is taken as really existent is in fact ultimately non-existent. Therefore, this [Māyājāla] Sūtra states that it is non-existent, due to the illusory object there is a sign but not substantiality. Being able to beguile and deceive one, it is known as a “deceiver of the eye.”

Mahayana

In Mahayana sutras, illusion is an important theme of the Prajñāpāramitā sutras. Here, the magician's illusion exemplifies how people misunderstand and misperceive reality, which is in fact empty of any essence and cannot be grasped. The Mahayana uses similar metaphors for illusion: magic, a dream, a bubble, a rainbow, lightning, the moon reflected in water, a mirage, and a city of celestial musicians." Understanding that what we experience is less substantial than we believe is intended to serve the purpose of liberation from ignorance, fear, and clinging and the attainment of enlightenment as a Buddha completely dedicated to the welfare of all beings. The Prajñaparamita texts also state that all dharmas (phenomena) are like an illusion, not just the five aggregates, but all beings, including Bodhisattvas and even Nirvana. The Prajñaparamita-ratnaguna-samcayagatha (Rgs) states:- This gnosis shows him all beings as like an illusion, Resembling a great crowd of people, conjured up at the crossroads, By a magician, who then cuts off many thousands of heads; He knows this whole living world as a magical creation, and yet remains without fear. Rgs 1:19

- Those who teach Dharma, and those who listen when it is being taught; Those who have won the fruition of a Worthy One, a Solitary Buddha, or a World Savior; And the nirvāṇa obtained by the wise and learned— All is born of illusion—so has the Tathāgata declared. - Rgs 2:5

Depending on the stage of the practitioner, the magical illusion is experienced differently. In the ordinary state, we get attached to our own mental phenomena, believing they are real, like the audience at a magic show gets attached to the illusion of a beautiful lady. At the next level, called actual relative truth, the beautiful lady appears, but the magician does not get attached. Lastly, at the ultimate level, the Buddha is not affected one way or the other by the illusion. Beyond conceptuality, the Buddha is neither attached nor non-attached. This is the middle way of Buddhism, which explicitly refutes the extremes of both eternalism and nihilism.

Nāgārjuna's Madhyamaka philosophy discusses nirmita, or illusion closely related to māyā. In this example, the illusion is a self-awareness that is, like the magical illusion, mistaken. For Nagarjuna, the self is not the organizing command center of experience, as we might think. Actually, it is just one element combined with other factors and strung together in a sequence of causally connected moments in time. As such, the self is not substantially real, but neither can it be shown to be unreal. The continuum of moments, which we mistakenly understand to be a solid, unchanging self, still performs actions and undergoes their results. "As a magician creates a magical illusion by the force of magic, and the illusion produces another illusion, in the same way the agent is a magical illusion and the action done is the illusion created by another illusion." What we experience may be an illusion, but we are living inside the illusion and bear the fruits of our actions there. We undergo the experiences of the illusion. What we do affects what we experience, so it matters. In this example, Nagarjuna uses the magician's illusion to show that the self is not as real as it thinks, yet, to the extent it is inside the illusion, real enough to warrant respecting the ways of the world.

For the Mahayana Buddhist, the self is māyā like a magic show and so are objects in the world. Vasubandhu's Trisvabhavanirdesa, a Mahayana Yogacara "Mind Only" text, discusses the example of the magician who makes a piece of wood appear as an elephant. The audience is looking at a piece of wood but, under the spell of magic, perceives an elephant instead. Instead of believing in the reality of the illusory elephant, we are invited to recognize that multiple factors are involved in creating that perception, including our involvement in dualistic subjectivity, causes and conditions, and the ultimate beyond duality. Recognizing how these factors combine to create what we perceive ordinarily, ultimate reality appears. Perceiving that the elephant is illusory is akin to seeing through the magical illusion, which reveals the dharmadhatu, or ground of being.

Tantra

Buddhist Tantra, a further development of the Mahayana, also makes use of the magician's illusion example in yet another way. In the completion stage of Buddhist Tantra, the practitioner takes on the form of a deity in an illusory body (māyādeha), which is like the magician's illusion. It is made of wind, or prana, and is called illusory because it appears only to other yogis who have also attained the illusory body. The illusory body has the markings and signs of a Buddha. There is an impure and a pure illusory body, depending on the stage of the yogi's practice.The concept that the world is an illusion is controversial in Buddhism. The Buddha does not state that the world is an illusion, but like an illusion. In the Dzogchen tradition the perceived reality is considered literally unreal, in that objects which make-up perceived reality are known as objects within one's mind, and that, as we conceive them, there is no pre-determined object, or assembly of objects in isolation from experience that may be considered the "true" object, or objects. As a prominent contemporary teacher puts it: "In a real sense, all the visions that we see in our lifetime are like a big dream [...]". In this context, the term visions denotes not only visual perceptions, but appearances perceived through all senses, including sounds, smells, tastes and tactile sensations.

Different schools and traditions in Tibetan Buddhism give different explanations of the mechanism producing the illusion usually called "reality".

| “ | The real sky is (knowing) that samsara and nirvana are merely an illusory display. | ” |

| — Mipham Rinpoche, Quintessential Instructions of Mind, p. 117 | ||

Even the illusory nature of apparent phenomena is itself an illusion. Ultimately, the yogi passes beyond a conception of things either existing or not existing, and beyond a conception of either samsara or nirvana. Only then is the yogi abiding in the ultimate reality.

Jainism

Jainism

Maya, in Jainism, means appearances or deceit that prevents one from Samyaktva (right belief). Maya is one of three causes of failure to reach right belief. The other two are Mithyatva (false belief) and Nidana (hankering after fame and worldly pleasures).

Maya is a closely related concept to Mithyatva, with Maya a source of wrong information while Mithyatva an individual's attitude to knowledge, with relational overlap.

Svetambara Jains classify categories of false belief under Mithyatva into five: Abhigrahika (false belief that is limited to one's own scriptures that one can defend, but refusing to study and analyze other scriptures); Anabhigrahika (false belief that equal respect must be shown to all gods, teachers, scriptures); Abhiniviseka (false belief resulting from pre-conceptions with a lack of discernment and refusal to do so); Samsayika (state of hesitation or uncertainty between various conflicting, inconsistent beliefs); and Anabhogika (innate, default false beliefs that a person has not thought through on one's own).

Digambara Jains classify categories of false belief under Mithyatva into seven: Ekantika (absolute, one sided false belief), Samsayika (uncertainty, doubt whether a course is right or wrong, unsettled belief, skepticism), Vainayika (false belief that all gods, gurus and scriptures are alike, without critical examination), Grhita (false belief derived purely from habits or default, no self-analysis), Viparita (false belief that true is false, false is true, everything is relative or acceptable), Naisargika (false belief that all living beings are devoid of consciousness and cannot discern right from wrong), Mudha-drsti (false belief that violence and anger can tarnish or damage thoughts, divine, guru or dharma).

Māyā (deceit) is also considered as one of four Kaṣaya (faulty passion, a trigger for actions) in Jain philosophy. The other three are Krodha (anger), Māna (pride) and Lobha (greed). The ancient Jain texts recommend that one must subdue these four faults, as they are source of bondage, attachment and non-spiritual passions.

When he wishes that which is good for him, he should get rid of the four faults — Krodha, Māna, Māyā and Lobha — which increase evil. Anger and pride when not suppressed, and deceit and greed when arising: all these four black passions water the roots of re-birth.

— Ārya Sayyambhava, Daśavaikālika sūtra, 8:36–39

Sikhism

Sikhism

In Sikhism, the world is regarded as both transitory and relatively real. God is viewed as the only reality, but within God exist both conscious souls and nonconscious objects; these created objects are also real. Natural phenomena are real but the effects they generate are unreal. māyā is as the events are real yet māyā is not as the effects are unreal. Sikhism believes that people are trapped in the world because of five vices: lust, anger, greed, attachment, and ego. Maya enables these five vices and makes a person think the physical world is "real," whereas, the goal of Sikhism is to rid the self of them. Consider the following example: In the moonless night, a rope lying on the ground may be mistaken for a snake. We know that the rope alone is real, not the snake. However, the failure to perceive the rope gives rise to the false perception of the snake. Once the darkness is removed, the rope alone remains; the snake disappears.

- Sakti adher jevarhee bhram chookaa nihchal siv ghari vaasaa.

In the darkness of māyā, I mistook the rope for the snake, but that is over, and now I dwell in the eternal home of the Lord.

(Sri Guru Granth Sahib 332). - Raaj bhuiang prasang jaise hahi ab kashu maram janaaiaa.

Like the story of the rope mistaken for a snake, the mystery has now been explained to me. Like the many bracelets, which I mistakenly thought were gold; now, I do not say what I said then. (Sri Guru Granth Sahib 658).

- Janam baritha jāṯ rang mā▫i▫ā kai. ||1|| rahā▫o.

You are squandering this life uselessly in the love of māyā.

Sri Guru Granth Sahib M.5 Guru Arjan Dev ANG 12

- Mā▫i▫ā mohi visāri▫ā jagaṯ piṯā parṯipāl.

In attachment to māyā, they have forgotten the Father, the Cherisher of the World.

Sri Guru Granth Sahib M3 Guru Amar Das ANG 30 - Ih sarīr mā▫i▫ā kā puṯlā vicẖ ha▫umai ḏustī pā▫ī.

This body is the puppet of māyā. The evil of egotism is within it.

Sri Guru Granth Sahib M3 Guru Amar Das - Bābā mā▫i▫ā bẖaram bẖulā▫e.

O Baba, māyā deceives with its illusion.

Sri Guru Granth Sahib M1 Guru Nanak Dev ANG 60 - "For that which we cannot see, feel, smell, touch, or understand, we

do not believe. For this, we are merely fools walking on the grounds of

great potential with no comprehension of what is."

Buddhist monk quotation