Artist's

impression of a major impact event. The collision between Earth and an

asteroid a few kilometres in diameter would release as much energy as

the simultaneous detonation of several million nuclear weapons.

Asteroid impact avoidance comprises a number of methods by which near-Earth objects (NEO) could be diverted, preventing destructive impact events. A sufficiently large impact by an asteroid or other NEOs would cause, depending on its impact location, massive tsunamis, multiple firestorms and an impact winter caused by the sunlight-blocking effect of placing large quantities of pulverized rock dust, and other debris, into the stratosphere.

A collision between the Earth and an approximately 10 kilometres

(6.2 miles)-wide object 66 million years ago is thought to have produced

the Chicxulub crater and the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, widely held responsible for the extinction of most dinosaurs.

While the chances of a major collision are low in the near term,

there is a high probability that one will happen eventually unless

defensive actions are taken. Recent astronomical events—such as the Shoemaker-Levy 9 impacts on Jupiter and the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor, along with the growing number of objects on the Sentry Risk Table—have drawn renewed attention to such threats. NASA warns that the Earth is unprepared for such an event.

In April 2018, the B612 Foundation reported "It's 100 per cent certain we'll be hit [by a devastating asteroid], but we're not 100 per cent sure when." Also in 2018, physicist Stephen Hawking,

in his final book Brief Answers to the Big Questions, considered an asteroid collision to be the biggest threat to the planet. In June 2018, the US National Science and Technology Council warned that America is unprepared for an asteroid impact event, and has developed and released the "National Near-Earth Object Preparedness Strategy Action Plan" to better prepare. According to expert testimony in the United States Congress in 2013, NASA would require at least five years of preparation before a mission to intercept an asteroid could be launched.

Deflection efforts

Known Near-Earth objects – as of January 2018

Video (0:55; July 23, 2018)

Video (0:55; July 23, 2018)

Most deflection efforts for a large object require from a year to

decades of warning, allowing time to prepare and carry out a collision

avoidance project, as no known planetary defense hardware has yet been

developed. It has been estimated that a velocity change of just 3.5/t × 10−2 m·s−1

(where t is the number of years until potential impact) is needed to

successfully deflect a body on a direct collision trajectory. In

addition, under certain circumstances, much smaller velocity changes are

needed. For example, it was estimated there was a high chance of 99942 Apophis swinging by Earth in 2029 with a 10−4

probability of passing through a 'keyhole' and returning on an impact

trajectory in 2035 or 2036. It was then determined that a deflection

from this potential return trajectory, several years before the

swing-by, could be achieved with a velocity change on the order of 10−6 ms−1.

An impact by a 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) asteroid on the Earth has historically caused an extinction-level event due to catastrophic damage to the biosphere. There is also the threat from comets entering the inner Solar System. The impact speed of a long-period comet would likely be several times greater than that of a near-Earth asteroid, making its impact much more destructive; in addition, the warning time is unlikely to be more than a few months.

Impacts from objects as small as 50 metres (160 ft) in diameter, which

are far more common, are historically extremely destructive regionally.

Finding out the material composition of the object is also

helpful before deciding which strategy is appropriate. Missions like the

2005 Deep Impact probe have provided valuable information on what to expect.

| “ | REP. STEWART: ... are we technologically capable of launching something that could intercept [an asteroid]? ... DR. A'HEARN: No. If we had spacecraft plans on the books already, that would take a year ... I mean a typical small mission ... takes four years from approval to start to launch ... | ” | |||

| — Rep. Chris Stewart (R, UT) and Dr. Michael F. A'Hearn, 10 April 2013, United States Congress | |||||

History of government mandates

The

1992 NASA-sponsored Near-Earth-Object Interception Workshop hosted by

Los Alamos National Laboratory evaluated issues involved in intercepting

celestial objects that could hit Earth. In a 1992 report to NASA, a coordinated Spaceguard

Survey was recommended to discover, verify and provide follow-up

observations for Earth-crossing asteroids. This survey was expected to

discover 90% of these objects larger than one kilometer within 25 years.

Three years later, another NASA report

recommended search surveys that would discover 60–70% of short-period,

near-Earth objects larger than one kilometer within ten years and obtain

90% completeness within five more years.

In 1998, NASA formally embraced the goal of finding and

cataloging, by 2008, 90% of all near-Earth objects (NEOs) with diameters

of 1 km or larger that could represent a collision risk to Earth. The

1 km diameter metric was chosen after considerable study indicated that

an impact of an object smaller than 1 km could cause significant local

or regional damage but is unlikely to cause a worldwide catastrophe. The impact of an object much larger than 1 km diameter could well result in worldwide damage up to, and potentially including, extinction of the human species.

The NASA commitment has resulted in the funding of a number of NEO

search efforts, which made considerable progress toward the 90% goal by

2008. However the 2009 discovery of several NEOs approximately 2 to 3

kilometers in diameter (e.g. 2009 CR2, 2009 HC82, 2009 KJ, 2009 MS and 2009 OG) demonstrated there were still large objects to be detected.

United States Representative George E. Brown, Jr. (D-CA) was quoted as voicing his support for planetary defense projects in Air & Space Power Chronicles,

saying "If some day in the future we discover well in advance that an

asteroid that is big enough to cause a mass extinction is going to hit

the Earth, and then we alter the course of that asteroid so that it does

not hit us, it will be one of the most important accomplishments in all

of human history."

Because of Congressman Brown's long-standing commitment to

planetary defense, a U.S. House of Representatives' bill, H.R. 1022, was

named in his honor: The George E. Brown, Jr. Near-Earth Object Survey

Act. This bill "to provide for a Near-Earth Object Survey program to

detect, track, catalogue, and characterize certain near-Earth asteroids

and comets" was introduced in March 2005 by Rep. Dana Rohrabacher (R-CA). It was eventually rolled into S.1281, the NASA Authorization Act of 2005, passed by Congress on December 22, 2005, subsequently signed by the President, and stating in part:

The U.S. Congress has declared that the general welfare and security of the United States require that the unique competence of NASA be directed to detecting, tracking, cataloguing, and characterizing near-Earth asteroids and comets in order to provide warning and mitigation of the potential hazard of such near-Earth objects to the Earth. The NASA Administrator shall plan, develop, and implement a Near-Earth Object Survey program to detect, track, catalogue, and characterize the physical characteristics of near- Earth objects equal to or greater than 140 meters in diameter in order to assess the threat of such near-Earth objects to the Earth. It shall be the goal of the Survey program to achieve 90% completion of its near-Earth object catalogue (based on statistically predicted populations of near-Earth objects) within 15 years after the date of enactment of this Act. The NASA Administrator shall transmit to Congress not later than 1 year after the date of enactment of this Act an initial report that provides the following: (A) An analysis of possible alternatives that NASA may employ to carry out the Survey program, including ground-based and space-based alternatives with technical descriptions. (B) A recommended option and proposed budget to carry out the Survey program pursuant to the recommended option. (C) Analysis of possible alternatives that NASA could employ to divert an object on a likely collision course with Earth.

The result of this directive was a report presented to Congress in early March 2007. This was an Analysis of Alternatives

(AoA) study led by NASA's Program Analysis and Evaluation (PA&E)

office with support from outside consultants, the Aerospace Corporation,

NASA Langley Research Center (LaRC), and SAIC (amongst others).

Ongoing projects

Number of NEOs detected by various projects.

NEOWISE – first four years of data starting in December 2013 (animated; April 20, 2018)

The Minor Planet Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts

has been cataloging the orbits of asteroids and comets since 1947. It

has recently been joined by surveys which specialize in locating the near-Earth objects

(NEO), many (as of early 2007) funded by NASA's Near Earth Object

program office as part of their Spaceguard program. One of the

best-known is LINEAR

that began in 1996. By 2004 LINEAR was discovering tens of thousands of

objects each year and accounting for 65% of all new asteroid

detections. LINEAR uses two one-meter telescopes and one half-meter telescope based in New Mexico.

Spacewatch, which uses a 90 centimeter telescope sited at the Kitt Peak Observatory

in Arizona, updated with automatic pointing, imaging, and analysis

equipment to search the skies for intruders, was set up in 1980 by Tom Gehrels and Robert S. McMillan of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory of the University of Arizona

in Tucson, and is now being operated by McMillan. The Spacewatch

project has acquired a 1.8 meter telescope, also at Kitt Peak, to hunt

for NEOs, and has provided the old 90 centimeter telescope with an

improved electronic imaging system with much greater resolution,

improving its search capability.

Other near-Earth object tracking programs include Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT), Lowell Observatory Near-Earth-Object Search (LONEOS), Catalina Sky Survey, Campo Imperatore Near-Earth Object Survey (CINEOS), Japanese Spaceguard Association, and Asiago-DLR Asteroid Survey. Pan-STARRS completed telescope construction in 2010, and it is now actively observing.

The Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System,

now in operation, conducts frequent scans of the sky with a view to

later-stage detection on the collision stretch of the asteroid orbit.

Those would be much too late for deflection, but still in time for

evacuation and preparation of the affected Earth region.

Another project, supported by the European Union, is NEOShield,

which analyses realistic options for preventing the collision of a NEO

with Earth. Their aim is to provide test mission designs for feasible

NEO mitigation concepts.The project particularly emphasises on two

aspects.

- The first one is the focus on technological development on essential techniques and instruments needed for guidance, navigation and control (GNC) in close vicinity of asteroids and comets. This will, for example, allow hitting such bodies with a high-velocity kinetic impactor spacecraft and observing them before, during and after a mitigation attempt, e.g., for orbit determination and monitoring.

- The second one focuses on refining Near Earth Object (NEO) characterisation. Moreover, NEOShield-2 will carry out astronomical observations of NEOs, to improve the understanding of their physical properties, concentrating on the smaller sizes of most concern for mitigation purposes, and to identify further objects suitable for missions for physical characterisation and NEO deflection demonstration.

"Spaceguard"

is the name for these loosely affiliated programs, some of which

receive NASA funding to meet a U.S. Congressional requirement to detect

90% of near-Earth asteroids over 1 km diameter by 2008.

A 2003 NASA study of a follow-on program suggests spending US$250–450

million to detect 90% of all near-Earth asteroids 140 meters and larger

by 2028.

NEODyS is an online database of known NEOs.

Sentinel Mission

The B612 Foundation is a private nonprofit foundation with headquarters in the United States, dedicated to protecting the Earth from asteroid strikes. It is led mainly by scientists, former astronauts and engineers from the Institute for Advanced Study, Southwest Research Institute, Stanford University, NASA and the space industry.

As a non-governmental organization

it has conducted two lines of related research to help detect NEOs that

could one day strike the Earth, and find the technological means to

divert their path to avoid such collisions. The foundation's current

goal is to design and build a privately financed asteroid-finding space telescope, Sentinel, to be launched in 2017–2018. The Sentinel's infrared telescope, once parked in an orbit similar to that of Venus,

will help identify threatening NEOs by cataloging 90% of those with

diameters larger than 140 metres (460 ft), as well as surveying smaller

Solar System objects.

Data gathered by Sentinel will help identify asteroids and other NEOs that pose a risk of collision with Earth, by being forwarded to scientific data-sharing networks, including NASA and academic institutions such as the Minor Planet Center. The foundation also proposes asteroid deflection of potentially dangerous NEOs by the use of gravity tractors to divert their trajectories away from Earth, a concept co-invented by the organization's CEO, physicist and former NASA astronaut Ed Lu.

Prospective projects

Orbit@home

intends to provide distributed computing resources to optimize search

strategy. On February 16, 2013, the project was halted due to lack of

grant funding.

However, on July 23, 2013, the orbit@home project was selected for

funding by NASA's Near Earth Object Observation program and was to

resume operations sometime in early 2014. As of July 13, 2018, the

project is offline according to its website.

The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, currently under construction, is expected to perform a comprehensive, high-resolution survey starting in the early 2020s.

Detection from space

On November 8, 2007, the House Committee on Science and Technology's Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics held a hearing to examine the status of NASA's Near-Earth Object survey program. The prospect of using the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer was proposed by NASA officials.

WISE surveyed the sky in the infrared band at a very high

sensitivity. Asteroids that absorb solar radiation can be observed

through the infrared band. It was used to detect NEOs, in addition to

performing its science goals. It is projected that WISE could detect 400

NEOs (roughly two percent of the estimated NEO population of interest)

within the one-year mission.

NEOSSat, the Near Earth Object Surveillance Satellite, is a microsatellite launched in February 2013 by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) that will hunt for NEOs in space. Further, Near-Earth Object WISE (NEOWISE), an extension of the WISE mission, started in September 2013, to hunt asteroids and comets close to the orbit of Earth.

Deep Impact

Research published in the March 26, 2009 issue of the journal Nature,

describes how scientists were able to identify an asteroid in space

before it entered Earth's atmosphere, enabling computers to determine

its area of origin in the Solar System as well as predict the arrival

time and location on Earth of its shattered surviving parts. The

four-meter-diameter asteroid, called 2008 TC3, was initially sighted by the automated Catalina Sky Survey telescope, on October 6, 2008. Computations correctly predicted that it would impact 19 hours after discovery and in the Nubian Desert of northern Sudan.

A number of potential threats have been identified, such as 99942 Apophis (previously known by its provisional designation 2004 MN4),

which in 2009 temporarily had an impact probability of about 3% for the

year 2029. Additional observations revised this probability down to

zero.

Impact probability calculation pattern

Why asteroid impact probability often goes up, then down.

The ellipses in the diagram on the right show the predicted position

of an example asteroid at closest Earth approach. At first, with only a

few asteroid observations, the error ellipse is very large and includes

the Earth. Further observations shrink the error ellipse, but it still

includes the Earth. This raises the predicted impact probability, since

the Earth now covers a larger fraction of the error region. Finally,

yet more observations (often radar observations, or discovery of a

previous sighting of the same asteroid on archival images) shrink the

ellipse revealing that the Earth is outside the error region, and the

impact probability is near zero.

For asteroids that are actually on track to hit Earth the

predicted probability of impact continues to increase as more

observations are made. This very similar pattern makes it difficult to

differentiate between asteroids which will only come close to Earth and

those which will actually hit it. This in turn makes it difficult to

decide when to raise an alarm as gaining more certainty takes time,

which reduces the time available to react to a predicted impact. However

raising the alarm too soon has the danger of causing a false alarm and creating a Boy Who Cried Wolf effect if the asteroid in fact misses Earth.

Collision avoidance strategies

Various

collision avoidance techniques have different trade-offs with respect

to metrics such as overall performance, cost, operations, and technology

readiness. There are various methods for changing the course of an asteroid/comet.

These can be differentiated by various types of attributes such as the

type of mitigation (deflection or fragmentation), energy source

(kinetic, electromagnetic, gravitational, solar/thermal, or nuclear),

and approach strategy (interception, rendezvous, or remote station).

Strategies fall into two basic sets: destruction and delay.

Fragmentation concentrates on rendering the impactor harmless by

fragmenting it and scattering the fragments so that they miss the Earth

or burn up in the atmosphere. Delay exploits the fact that both the

Earth and the impactor are in orbit. An impact occurs when both reach

the same point in space at the same time, or more correctly when some

point on Earth's surface intersects the impactor's orbit when the

impactor arrives. Since the Earth

is approximately 12,750 km in diameter and moves at approx. 30 km per

second in its orbit, it travels a distance of one planetary diameter in

about 425 seconds, or slightly over seven minutes. Delaying, or

advancing the impactor's arrival by times of this magnitude can,

depending on the exact geometry of the impact, cause it to miss the

Earth.

Collision avoidance strategies can also be seen as either direct,

or indirect and in how rapidly they transfer energy to the object. The

direct methods, such as nuclear explosives, or kinetic impactors,

rapidly intercept the bolide's path. Direct methods are preferred

because they are generally less costly in time and money. Their effects

may be immediate, thus saving precious time. These methods would work

for short-notice, and long-notice threats, and are most effective

against solid objects that can be directly pushed, but in the case of

kinetic impactors, they are not very effective against large loosely

aggregated rubble piles. The indirect methods, such as gravity tractors,

attaching rockets or mass drivers, are much slower and require

traveling to the object, time to change course up to 180 degrees to fly

alongside it, and then take much more time to change the asteroid's path

just enough so it will miss Earth.

Many NEOs are thought to be "flying rubble piles"

only loosely held together by gravity, and a typical spacecraft sized

kinetic-impactor deflection attempt might just break up the object or

fragment it without sufficiently adjusting its course.

If an asteroid breaks into fragments, any fragment larger than 35

meters across would not burn up in the atmosphere and itself could

impact Earth. Tracking the thousands of buckshot-like

fragments that could result from such an explosion would be a very

daunting task, although fragmentation would be preferable to doing

nothing and allowing the originally larger rubble body, which is

analogous to a shot and wax slug, to impact the Earth.

In Cielo

simulations conducted in 2011–2012, in which the rate and quantity of

energy delivery were sufficiently high and matched to the size of the

rubble pile, such as following a tailored nuclear explosion, results

indicated that any asteroid fragments, created after the pulse of energy

is delivered, would not pose a threat of re-coalescing (including for those with the shape of asteroid Itokawa) but instead would rapidly achieve escape velocity from their parent body (which for Itokawa is about 0.2 m/s) and therefore move out of an earth-impact trajectory.

Nuclear explosive device

In a similar manner to the earlier pipes filled with a partial pressure of helium, as used in the Ivy Mike test of 1952, the 1954 Castle Bravo test was likewise heavily instrumented with Line-of-Sight(LOS) pipes,

to better define and quantify the timing and energies of the x-rays and

neutrons produced by these early thermonuclear devices.

One of the outcomes of this diagnostic work resulted in this graphic

depiction of the transport of energetic x-ray and neutrons through a

vacuum line, some 2.3 km long, whereupon it heated solid matter at the

"station 1200" blockhouse and thus generated a secondary fireball.

Initiating a nuclear explosive device above, on, or slightly beneath,

the surface of a threatening celestial body is a potential deflection

option, with the optimal detonation height dependent upon the

composition and size of the object.

It does not require the entire NEO to be vaporized to mitigate an

impact threat. In the case of an inbound threat from a "rubble pile,"

the stand off,

or detonation height above the surface configuration, has been put

forth as a means to prevent the potential fracturing of the rubble pile. The energetic neutrons and soft X-rays released by the detonation, which do not appreciably penetrate matter, are converted into thermal heat upon encountering the object's surface matter, ablatively vaporizing all line of sight exposed surface areas of the object to a shallow depth, turning the surface material it heats up into ejecta, and, analogous to the ejecta from a chemical rocket engine exhaust, changing the velocity, or "nudging", the object off course by the reaction, following Newton's third law, with ejecta going one way and the object being propelled in the other. Depending on the energy of the explosive device, the resulting rocket exhaust

effect, created by the high velocity of the asteroid's vaporized mass

ejecta, coupled with the object's small reduction in mass, would produce

enough of a change in the object's orbit in order to avoid hitting the

Earth.

A Hypervelocity Asteroid Mitigation Mission for Emergency Response (HAMMER) has been proposed.

Stand-off approach

If

the object is very large but is still a loosely held together rubble

pile, a solution is to detonate one or a series of nuclear explosive

devices alongside the asteroid, at a 20-meter or greater stand-off

height above its surface, so as not to fracture the potentially loosely

held together object. Providing this stand-off

strategy was done far enough in advance, the force from a sufficient

number of nuclear blasts would be enough to alter the object's

trajectory to avoid an impact, according to computer simulations and

experimental evidence from meteorites exposed to the thermal X-ray pulses of the Z-machine.

The 1964 book Islands in Space calculates that the nuclear megatonnage necessary for several deflection scenarios exists.

In 1967, graduate students under Professor Paul Sandorff at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology were tasked with designing a method to prevent a hypothetical 18 month distant impact on Earth by the 1.4 kilometer wide asteroid 1566 Icarus, an object which makes regular close approaches to Earth, sometimes as close as 16 lunar distances.

To achieve the task within the timeframe and with limited material

knowledge of the asteroid's composition, a variable stand-off system was

conceived. This would have used a number of modified Saturn V

rockets sent on interception courses and the creation of a handful of

nuclear explosive devices in the 100 megaton energy

range—coincidentally, the maximum yield of the Soviets' 27 metric-tonne

mass, 1961 Tsar Bomba if a uranium tamper had been used—as each rocket vehicle's payload. The design study was later published as Project Icarus which served as the inspiration for the 1979 film Meteor.

A NASA analysis of deflection alternatives, conducted in 2007, stated:

Nuclear standoff explosions are assessed to be 10–100 times more effective than the non-nuclear alternatives analyzed in this study. Other techniques involving the surface or subsurface use of nuclear explosives may be more efficient, but they run an increased risk of fracturing the target NEO. They also carry higher development and operations risks.

In the same year NASA released a study where the asteroid Apophis (with a diameter ~300 m) was assumed to have a much lower rubble pile density (1,500 kg/m3)

and therefore mass than is now known, and in the study, it is assumed

to be on an impact trajectory with Earth for the year 2029. Under these

hypothetical conditions, the report determines that a "Cradle

spacecraft" would be sufficient to deflect it from Earth impact. This

conceptual spacecraft contains six B83 physics packages, each set for their maximum 1.2 megatonne yield that are bundled together and lofted by an Ares V vehicle sometime in the 2020s, with each B83 being fuzed

to detonate over the asteroid's surface at a height of 100 m ("1/3 of

the objects diameter" as its stand-off), one after the other, with hour

long intervals between each successive detonation. The results of this

study indicated that a single employment of this "option can deflect

NEOs of [100-500m diameter] two years before impact, and larger NEOs

with at least five years warning".

These effectiveness figures are considered to be "conservative" by its

authors and only the thermal X-ray output of the B83 devices was

considered, while neutron heating was neglected for ease of calculation

purposes.

Surface and subsurface use

The director of the Asteroid Deflection Research Center at Iowa State University, Wie, who had published kinetic impactor deflection studies in the past,

began in 2011 to study strategies that could deal with 50 to 500 meter

diameter objects when the time to Earth impact was under a year or so.

He concluded that to provide the required energy, a nuclear explosion or

other events that could deliver the same power, are the only methods

that can work against a very large asteroid within these time

constraints.

This work resulted in the creation of a conceptual Hypervelocity Asteroid Intercept Vehicle (HAIV), which combines a kinetic impactor to create an initial crater

for a follow-up subsurface nuclear detonation within that initial

crater, which would generate a high degree of efficiency in the

conversion of the nuclear energy that is released in the detonation into

propulsion energy to the asteroid.

Another proposed approach along similar lines is the use of a

surface detonating nuclear device, in place of the prior mentioned

kinetic impactor, in order to create the initial crater, with the

resulting crater that forms then again being used as a rocket nozzle to channel succeeding nuclear detonations.

At the 2014 NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts

(NIAC) conference, Wie and his colleagues stated that, "We have the

solution, using our baseline concept, to be able to mitigate the

asteroid-impact threat, with any range of warning." For example,

according to their computer models, with a warning time of 30 days a

1,000-foot-wide (300 m) asteroid would be neutralized by using a single

HAIV, with less than 0.1 percent of the destroyed object's mass

potentially striking Earth, which by comparison would be more than

acceptable.

As of 2015 Wie has collaborated with the Danish Emergency Asteroid Defence Project (EADP), which ultimately intends to crowdsource

sufficient funds to design, build and store a non-nuclear HAIV

spacecraft as planetary insurance. For threatening asteroids too large

and/or too close to Earth impact to effectively be deflected by the

non-nuclear HAIV approach, nuclear explosive devices with 5% of the

explosive yield in this configuration than when compared to the

stand-off strategy are intended to be swapped-in, under international

oversight, when conditions arise that necessitate it.

Comet deflection possibility

Following the 1994 Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet impacts with Jupiter, Edward Teller proposed to a collective of U.S. and Russian ex-Cold War weapons designers in a 1995 planetary defense workshop meeting at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), that they collaborate to design a 1 gigaton nuclear explosive device, which would be equivalent to the kinetic energy of a 1 km diameter asteroid. The theoretical 1 Gt device would weigh about 25–30 tons, light enough to be lifted on the Energia rocket and it could be used to instantaneously vaporize a 1 km asteroid, divert the paths of extinction event class asteroids

(greater than 10 km in diameter) within a few months of short notice,

while with 1-year notice, at an interception location no closer than Jupiter, it would also be capable of dealing with the even rarer short period comets which can come out of the Kuiper belt and transit past Earth orbit within 2 years. For comets of this class, with a maximum estimated 100 km diameter, Charon served as the hypothetical threat.

In 2013, the related National Laboratories of the US and Russia signed a deal that includes an intent to cooperate on defense from asteroids.

Present capability

An April 2014 GAO report notes that the NNSA is retaining canned subassemblies

(CSAs) " in an indeterminate state pending a senior-level government

evaluation of their use in planetary defense against earthbound

asteroids." In its FY2015 budget request, the NNSA noted that the 9 Mt B53

component disassembly was "delayed", leading some observers to conclude

they might be the warhead CSAs being retained for potential planetary

defense purposes. Following the total disassembly of all 25 Mt high yield B41s in 1976, the B53 is the highest yielding US device presently in the Enduring Stockpile.

Law

The use of nuclear explosive devices is an international issue and will need to be addressed by the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. The 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

technically bans nuclear weapons in space. However it is unlikely that a

nuclear explosive device, fuzed to be detonated only upon interception

with a threatening celestial object,

with the sole intent of preventing that celestial body from impacting

Earth would be regarded as an un-peaceful use of space, or that the

explosive device sent to mitigate an Earth impact, explicitly designed

to prevent harm to come to life would fall under the classification of a

"weapon".

Kinetic impact

The Deep Impact collision encounter with comet Tempel 1 (8 x 5 km in dimensions). The impact flash and resulting ejecta are clearly visible. The impactor delivered 19 gigajoules (the equivalent of 4.8 tons of TNT) upon impact. It generated a predicted 0.0001 mm/s velocity change in the comet's orbital motion and decreased its perihelion distance by 10 meters. After the impact, a newspaper reported that the orbit of comet Tempel 1 was changed by 10 cm (3.9 in)."

The impact of a massive object, such as a spacecraft or even another

near-Earth object, is another possible solution to a pending NEO impact.

An object with a high mass close to the Earth could be sent out into a

collision course with the asteroid, knocking it off course.

When the asteroid is still far from the Earth, a means of deflecting the asteroid is to directly alter its momentum by colliding a spacecraft with the asteroid.

A NASA analysis of deflection alternatives, conducted in 2007, stated:

Non-nuclear kinetic impactors are the most mature approach and could be used in some deflection/mitigation scenarios, especially for NEOs that consist of a single small, solid body.

The European Space Agency (ESA) is studying the preliminary design of two space missions for ~2020, named AIDA (formerly Don Quijote), and if flown, they would be the first intentional asteroid deflection mission ever designed. ESA's Advanced Concepts Team has also demonstrated theoretically that a deflection of 99942 Apophis could be achieved by sending a simple spacecraft weighing less than one ton to impact against the asteroid. During a trade-off study one of the leading researchers argued that a strategy called 'kinetic impactor deflection' was more efficient than others.

The European Union's NEOShield-2 Mission

is also primarily studying the Kinetic Impactor mitigation method. The

principle of the kinetic impactor mitigation method is that the NEO or

Asteroid is deflected following an impact from an impactor spacecraft.

The principle of momentum transfer is used, as the impactor crashes into

the NEO at a very high velocity of 10 km/s or more. The mass and

velocity of the impactor (the momentum) are transferred to the NEO,

causing a change in velocity and therefore making it deviate from its

course slightly.

As of mid-2018, the AIDA mission has been partly approved. The NASA Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART)

kinetic impactor spacecraft has entered phase C (detailed definition).

The goal os to impact the 180-m asteroidal moon of Near-Earth Asteroid 65803 Didymos, nicknamed Didymoon.

The impact will occur in October 2022 when Didymos is relatively close

to Earth, allowing Earth-based telescopes and planetary radar to

observe the event. The result of the impact will be to change the

orbital velocity and hence orbital period of Didymoon, by a large enough

amount that it can be measured from Earth. This will show for the first

time that it is possible to change the orbit of a small ~200m diameter

asteroid, around the size most likely to require active mitigation in

the future. The second part of the AIDA mission - the ESA HERA

spacecraft - has entered phase B (Preliminary Definition) and requires

approval by ESA member states in October 2019. If approved, it would

reach the Didymos system in 2024 and measure both the mass of Didymoon and the precise effect of the impact on that body, allowing much better extrapolation of the AIDA mission to other targets.

Asteroid gravity tractor

One more alternative to explosive deflection is to move the asteroid

slowly over a time. Tiny constant thrust accumulates to deviate an

object sufficiently from its predicted course. Edward T. Lu and Stanley G. Love

have proposed using a large heavy unmanned spacecraft hovering over an

asteroid to gravitationally pull the latter into a non-threatening

orbit. The spacecraft and the asteroid mutually attract one another. If

the spacecraft counters the force towards the asteroid by, e.g., an ion thruster,

the net effect is that the asteroid is accelerated towards the

spacecraft and thus slightly deflected from its orbit. While slow, this

method has the advantage of working irrespective of the asteroid

composition or spin rate – rubble pile

asteroids would be difficult to deflect by means of nuclear detonations

while a pushing device would be hard or inefficient to mount on a fast

rotating asteroid. A gravity tractor would likely have to spend several

years beside the asteroid to be effective.

A NASA analysis of deflection alternatives, conducted in 2007, stated:

"Slow push" mitigation techniques are the most expensive, have the lowest level of technical readiness, and their ability to both travel to and divert a threatening NEO would be limited unless mission durations of many years to decades are possible.

Ion beam shepherd

Another "contactless" asteroid deflection technique has been recently proposed by C.Bombardelli and J.Peláez from the Technical University of Madrid.

The method involves the use of a low divergence ion thruster pointed at

the asteroid from a nearby hovering spacecraft. The momentum

transmitted by the ions reaching the asteroid surface produces a slow

but continuous force that can deflect the asteroid in a similar way as

done by the gravity tractor but with a lighter spacecraft.

Use of focused solar energy

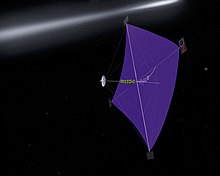

NASA study of a solar sail. The sail would be 0.5 km wide.

H. Jay Melosh proposed deflecting an asteroid or comet by focusing solar energy onto its surface to create thrust from the resulting vaporization of material, or to amplify the Yarkovsky effect. Over a span of months or years enough solar radiation can be directed onto the object to deflect it.

This method would first require the construction of a space station with a system of gigantic lenses. Then the station would be transported toward the Sun.

Mass driver

A mass driver

is an (automated) system on the asteroid to eject material into space

thus giving the object a slow steady push and decreasing its mass. A

mass driver is designed to work as a very low specific impulse system, which in general uses a lot of propellant, but very little power.

The idea is that when using local material as propellant, the

amount of propellant is not as important as the amount of power, which

is likely to be limited.

Another possibility is to use a mass driver on the Moon aimed at

the NEO to take advantage of the Moon's orbital velocity and

inexhaustible supply of "rock bullets".

Conventional rocket engine

Attaching any spacecraft propulsion

device would have a similar effect of giving a push, possibly forcing

the asteroid onto a trajectory that takes it away from Earth. An

in-space rocket engine that is capable of imparting an impulse of 106

N·s (E.g. adding 1 km/s to a 1000 kg vehicle), will have a relatively

small effect on a relatively small asteroid that has a mass of roughly a

million times more. Chapman, Durda, and Gold's white paper calculates deflections using existing chemical rockets delivered to the asteroid.

Such direct force rocket engines are typically proposed to use highly-efficient electrically powered spacecraft propulsion, such as ion thrusters or VASIMR.

Asteroid laser ablation

This early Asteroid Redirect Mission artist's impression is suggestive of another method of changing a large threatening celestial body's orbit by capturing

relatively smaller celestial objects and using those, and not the

usually proposed small bits of spacecraft, as the means of creating a

powerful kinetic impact, or alternatively, a stronger faster acting gravitational tractor, as some low-density asteroids such as 253 Mathilde can dissipate impact energy.

Similar to the effects of a nuclear device, it is thought possible to

focus sufficient laser energy on the surface of an asteroid to cause

flash vaporization / ablation to create either in impulse or to ablate

away the asteroid mass. This concept, called asteroid laser ablation was articulated in the 1995 SpaceCast 2020 white paper "Preparing for Planetary Defense", and the 1996 Air Force 2025 white paper "Planetary Defense: Catastrophic Health Insurance for Planet Earth".

Early publications include C. R. Phipps "ORION" concept from 1996,

Colonel Jonathan W. Campbell's 2000 monograph "Using Lasers in Space:

Laser Orbital Debris Removal and Asteroid Deflection", and NASA's 2005 concept Comet Asteroid Protection System (CAPS). Typically such systems require a significant amount of power, such as would be available from a Space-Based Solar Power Satellite.

The 1984 Strategic Defense Initiative concept of a generic space based Nuclear reactor pumped laser or a hydrogen fluoride laser satellite, firing on a target, causing a momentum change in the target object by laser ablation. With the proposed Space Station Freedom(ISS) in the background.

Another proposal is the Phillip Lubin's DE-STAR proposal.

- The DE-STAR project, proposed by researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, is a concept modular solar powered 1 µm, near infrared wavelength, laser array. The design calls for the array to eventually be approximately 1 km squared in size, with the modular design meaning that it could be launched in increments and assembled in space. In its early stages as a small array it could deal with smaller targets, assist solar sail probes and would also be useful in cleaning up space debris.

Other proposals

- Wrapping the asteroid in a sheet of reflective plastic such as aluminized PET film as a solar sail

- "Painting" or dusting the object with titanium dioxide (white) to alter its trajectory via increased reflected radiation pressure or with soot (black) to alter its trajectory via the Yarkovsky effect.

- Planetary scientist Eugene Shoemaker in 1996 proposed deflecting a potential impactor by releasing a cloud of steam in the path of the object, hopefully gently slowing it. Nick Szabo in 1990 sketched a similar idea, "cometary aerobraking", the targeting of a comet or ice construct at an asteroid, then vaporizing the ice with nuclear explosives to form a temporary atmosphere in the path of the asteroid.

- Coherent digger array multiple 1 ton flat tractors able to dig and expel asteroid soil mass as a coherent fountain array, coordinated fountain activity may propel and deflect over years.

- Attaching a tether and ballast mass to the asteroid to alter its trajectory by changing its center of mass.

- Magnetic Flux Compression to magnetically brake and or capture objects that contain a high percentage of meteoric iron by deploying a wide coil of wire in its orbital path and when it passes through, Inductance creates an electromagnet solenoid to be generated.

Deflection technology concerns

Carl Sagan, in his book Pale Blue Dot, expressed concern about deflection technology that any method capable of deflecting impactors away from Earth could also be abused to divert non-threatening bodies toward

the planet. Considering the history of genocidal political leaders and

the possibility of the bureaucratic obscuring of any such project's true

goals to most of its scientific participants, he judged the Earth at

greater risk from a man-made impact than a natural one. Sagan instead

suggested that deflection technology be developed only in an actual

emergency situation.

All low-energy delivery deflection technologies have inherent

fine control and steering capability, making it possible to add just the

right amount of energy to steer an asteroid originally destined for a mere close approach toward a specific Earth target.

According to Rusty Schweickart, the gravitational tractor

method is controversial because, during the process of changing an

asteroid's trajectory, the point on the Earth where it could most likely

hit would be slowly shifted across different countries. Thus, the

threat for the entire planet would be minimized at the cost of some

specific states' security. In Schweickart's opinion, choosing the way

the asteroid should be "dragged" would be a tough diplomatic decision.

Analysis of the uncertainty involved in nuclear deflection shows

that the ability to protect the planet does not imply the ability to

target the planet. A nuclear explosion that changes an asteroid's

velocity by 10 meters/second (plus or minus 20%) would be adequate to

push it out of an Earth-impacting orbit. However, if the uncertainty of

the velocity change was more than a few percent, there would be no

chance of directing the asteroid to a particular target.

Planetary defense timeline

- In their 1964 book, Islands in Space, Dandridge M. Cole and Donald W. Cox noted the dangers of planetoid impacts, both those occurring naturally and those that might be brought about with hostile intent. They argued for cataloging the minor planets and developing the technologies to land on, deflect, or even capture planetoids.

- In 1967, students in the Aeronautics and Astronautics department at MIT did a design study, "Project Icarus," of a mission to prevent a hypothetical impact on Earth by asteroid 1566 Icarus. The design project was later published in a book by the MIT Press and received considerable publicity, for the first time bringing asteroid impact into the public eye.

- In the 1980s NASA studied evidence of past strikes on planet Earth, and the risk of this happening at the current level of civilization. This led to a program that maps which objects in the Solar System both cross Earth's orbit and are large enough to cause serious damage if they ever hit.

- In the 1990s, US Congress held hearings to consider the risks and what needed to be done about them. This led to a US$3 million annual budget for programs like Spaceguard and the near-Earth object program, as managed by NASA and USAF.

- In 2005 a number of astronauts published an open letter through the Association of Space Explorers calling for a united push to develop strategies to protect Earth from the risk of a cosmic collision.

- It is currently (as of late 2007) estimated that there are approximately 20,000 objects capable of crossing Earth's orbit and large enough (140 meters or larger) to warrant concern. On the average, one of these will collide with Earth every 5,000 years, unless preventative measures are undertaken. It is now anticipated that by year 2008, 90% of such objects that are 1 km or more in diameter will have been identified and will be monitored. The further task of identifying and monitoring all such objects of 140m or greater is expected to be complete around 2020.

- The Catalina Sky Survey (CSS) is one of NASA´s four funded surveys to carry out a 1998 U.S. Congress mandate to find and catalog by the end of 2008, at least 90 percent of all near-Earth objects (NEOs) larger than 1 kilometer across. CSS discovered over 1150 NEOs in years 2005 to 2007. In doing this survey they discovered on November 20, 2007, an asteroid, designated 2007 WD5, which initially was estimated to have a chance of hitting Mars on January 30, 2008, but further observations during the following weeks allowed NASA to rule out an impact. NASA estimated a near miss by 26,000 kilometres (16,000 mi).

- In January 2012, after a near pass-by of object 2012 BX34, a paper entitled "A Global Approach to Near-Earth Object Impact Threat Mitigation," is released by researchers from Russia, Germany, the United States, France, Britain and Spain which discusses the "NEOShield" project.

Fictional representations

Asteroid or comet impacts are a common subgenre of disaster fiction,

and such stories typically feature some attempt—successful or

unsuccessful—to prevent the catastrophe. Most involve trying to destroy

or explosively redirect an object.

Film

- When Worlds Collide (1951): A science fiction film based on the 1933 novel; shot in Technicolor, directed by Rudolph Maté and the winner of the 1952 Academy Awards for special effects.

- 1979 film Meteor, based on the MIT Project Icarus study.

- Armageddon (1998): A pair of modified Space Shuttle orbiters, called "X-71s", and the Mir are used to drill a hole in an asteroid and plant a nuclear bomb.

- Deep Impact (1998): A manned spacecraft, the Messiah, based on Project Orion, plants a number of nuclear bombs on a comet.

- Melancholia (2011): The film's story revolves around two sisters, one of whom is preparing to marry, as a rogue planet is about to collide with Earth.

- Seeking A Friend For The End Of The World (2012): After several unsuccessful attempts to stop an asteroid, humanity is given only three weeks to live, sending the world into sheer chaos, and bringing two unlikely people together in the wake of annihilation.

- These Final Hours (2013): Two lovers and the inhabitants of Perth, Australia await a cataclysmic firestorm caused by the impact of an asteroid in the North Atlantic.

- Tik Tik Tik (2018): There is space station with a nuclear missile that can destroy the rogue asteroid. The in-charge of that space station seems to be in a quarrel with India. So, they enlist the service of a local magician to go into space and save the lives of millions of Indians

Literature

- Lucifer's Hammer (1977): A comet, which was initially thought unlikely to strike, hits the Earth, resulting in the end of civilization and a decline into tribal warfare over food and resources. Written by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle.

- The Hammer of God (1993): A spacecraft is sent to divert a massive asteroid by using thrusters. Written by Arthur C. Clarke.

- Titan (1997): The Chinese, to retaliate for biological attacks by the US, cause a huge explosion next to an asteroid (2002OA), with the aim of deflecting it into Earth orbit and threatening the world with targeted precision strikes in the future. Unfortunately, their calculations are wrong as they didn't take into account the size of the asteroid which could cause a Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. The asteroid strikes Earth, critically damaging the planetary ecosystem. Written by Stephen Baxter.

- Moonfall (1998): A comet is in collision course with the Moon. After the collision, the debris start falling on Earth. Written by Jack McDevitt.

- Nemesis (1998): The US government gathers a small team, including a British astronomer, with instructions to find and deflect an asteroid already targeted at North America by the Russians. Written by British astronomer Bill Napier.

Television

- Star Trek: In "The Paradise Syndrome" (1968), an amnesiac Kirk finds a centuries-old obelisk which has a deflector beam built in to deflect an asteroid coming to wipe out a primitive race.

- Horizon: Hunt for the Doomsday Asteroid (1994), a BBC documentary, part of the Horizon science series, Season 30, Episode 7.

- NOVA: Doomsday Asteroid (1995), a PBS NOVA science documentary, Series 23, Episode 4.

- Futurama: The episode "A Big Piece of Garbage" (1999), features a large space object on a collision course with Earth which turns out to be a giant ball of garbage launched into space by New York City around 2052. Residents of New New York first try blowing up the ball to destroy it but fail as the rocket is absorbed by the ball. They then deflect it using a newly created near-identical garbage ball.

- Defenders of the Planet (2001), a three-part British TV mini-series discussing the individuals and organizations working to defend the Earth against killer asteroids and other extraterrestrial threats; broadcast on The Learning Channel.[127]

- Danny Phantom: In the series finale episodes "Phantom Planet" an asteroid is on a collision course with Earth. Danny convinces Earth's ghosts to turn the Earth intangible, avoiding disaster.

- The Sarah Jane Adventures: In "Whatever Happened to Sarah Jane?" (2007), a meteor on a collision course with the Earth is ultimately deflected back into space by Sarah Jane's alien computer, Mr. Smith.

- You, Me and the Apocalypse: In this series, a comet is on a collision course with the Earth and collides after a failed attempt to deflect said comet.

- One-Punch Man: The episode "The Ultimate Disciple" features the superheroes Genos and Metal Knight attempting to destroy a meteor on a collision course with a city. After failing to do so, the titular superhero Saitama destroys the meteor in one punch, inadvertently causing the meteor to shatter in smaller pieces, devastating the city.

- Salvation (2017) centers on the ramifications of the discovery of an asteroid that will impact the Earth in just six months and the attempts to prevent it.

Video games

- Ace Combat 04: Shattered Skies (2001): In this combat flight simulator for the PlayStation 2 by Namco, a railgun battery is used in an attempt to destroy a massive asteroid with limited success.

- Mass Effect (2007): The "Bring Down the Sky" expansion features an alien extremist group that attempts to hijack an asteroid station and set it on a collision course with a human colony.

- Outpost (1994): The game's plot mentions how an attempt to divert the path of the asteroid Vulcan's Hammer, in collision course with Earth, using a nuclear weapon fails and instead causes it to break in two large pieces that strike Earth.

- In Terminal Velocity, the aggressors install an ion drive on Ceres to direct it towards Earth.