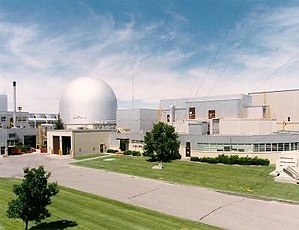

Experimental Breeder Reactor II, which served as the prototype for the Integral Fast Reactor

The integral fast reactor (IFR, originally advanced liquid-metal reactor) is a design for a nuclear reactor using fast neutrons and no neutron moderator (a "fast" reactor). IFR would breed more fuel and is distinguished by a nuclear fuel cycle that uses reprocessing via electrorefining at the reactor site.

IFR development began in 1984 and the U.S. Department of Energy built a prototype, the Experimental Breeder Reactor II.

On April 3, 1986, two tests demonstrated the inherent safety of the IFR

concept. These tests simulated accidents involving loss of coolant

flow. Even with its normal shutdown devices disabled, the reactor shut

itself down safely without overheating anywhere in the system. The IFR

project was canceled by the US Congress in 1994, three years before completion.

The proposed Generation IV Sodium-Cooled Fast Reactor is its closest surviving fast breeder reactor design. Other countries have also designed and operated fast reactors.

S-PRISM (from SuperPRISM), also called PRISM (Power Reactor Innovative Small Module), is the name of a nuclear power plant design by GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy (GEH) based on the Integral Fast Reactor.

Overview

The IFR is cooled by liquid sodium or lead and fueled by an alloy of uranium and plutonium. The fuel is contained in steel cladding with liquid sodium filling in the space between the fuel and the cladding. A void above the fuel allows helium and radioactive xenon

to be collected safely without significantly increasing pressure inside

the fuel element, and also allows the fuel to expand without breaching

the cladding, making metal rather than oxide fuel practical.

The advantage of lead as opposed to sodium is that it is not

reactive chemically, especially with water or air. The disadvantages

are that liquid lead is far more viscous than liquid sodium (increasing

pumping costs), and there are numerous radioactive neutron activation

products, while there are essentially none from sodium.

Basic design decisions

Metallic fuel

Metal

fuel with a sodium-filled void inside the cladding to allow fuel

expansion has been demonstrated in EBR-II. Metallic fuel makes

pyroprocessing the reprocessing technology of choice.

Fabrication of metallic fuel is easier and cheaper than ceramic (oxide) fuel, especially under remote handling conditions.

Metallic fuel has better heat conductivity and lower heat capacity than oxide, which has safety advantages.

Sodium coolant

Use

of liquid metal coolant removes the need for a pressure vessel around

the reactor. Sodium has excellent nuclear characteristics, a high heat

capacity and heat transfer capacity, low viscosity, a reasonably low

melting point and a high boiling point, and excellent compatibility with

other materials including structural materials and fuel. The high heat

capacity of the coolant and the elimination of water from the core

increase the inherent safety of the core.

Pool design rather than loop

Containing all of the primary coolant in a pool produces several safety and reliability advantages.

Onsite reprocessing using pyroprocessing

Reprocessing

is essential to achieve most of the benefits of a fast reactor,

improving fuel usage and reducing radioactive waste each by several

orders of magnitude.

Onsite processing is what makes the IFR integral. This and the use of pyroprocessing both reduce proliferation risk.

Pyroprocessing (using an electrorefiner) has been demonstrated at EBR-II as practical on the scale required. Compared to the PUREX

aqueous process, it is economical in capital cost, and is unsuitable

for production of weapons material, again unlike PUREX which was

developed for weapons programs.

Pyroprocessing makes metallic fuel the fuel of choice. The two decisions are complementary.

Summary

The

four basic decisions of metallic fuel, sodium coolant, pool design, and

onsite reprocessing by electrorefining, are complementary, and produce a

fuel cycle that is proliferation resistant and efficient in fuel usage,

and a reactor with a high level of inherent safety, while minimizing

the production of high-level waste. The practicality of these decisions

has been demonstrated over many years of operation of EBR-II.

Advantages

- Breeder reactors (such as the IFR) could in principle extract almost all of the energy contained in uranium or thorium, decreasing fuel requirements by nearly two orders of magnitude compared to traditional once-through reactors, which extract less than 0.65% of the energy in mined uranium, and less than 5% of the enriched uranium with which they are fueled. This could greatly dampen concern about fuel supply or energy used in mining.

- Fast reactors can "burn" long lasting nuclear transuranic waste (TRU) waste components (actinides: reactor-grade plutonium and minor actinides), turning liabilities into assets. Another major waste component, fission products (FP), would stabilize at a lower level of radioactivity than the original natural uranium ore it was attained from in two to four centuries, rather than tens of thousands of years. The fact that 4th generation reactors are being designed to use the waste from 3rd generation plants could change the nuclear story fundamentally—potentially making the combination of 3rd and 4th generation plants a more attractive energy option than 3rd generation by itself would have been, both from the perspective of waste management and energy security.

- The use of a medium-scale reprocessing facility onsite, and the use of pyroprocessing rather than aqueous reprocessing, is claimed to considerably reduce the proliferation potential of possible diversion of fissile material as the processing facility is in-situ/integral.

Safety

In traditional light water reactors

(LWRs) the core must be maintained at a high pressure to keep the water

liquid at high temperatures. In contrast, since the IFR is a liquid metal cooled reactor, the core could operate at close to ambient pressure, dramatically reducing the danger of a loss-of-coolant accident. The entire reactor core, heat exchangers

and primary cooling pumps are immersed in a pool of liquid sodium or

lead, making a loss of primary coolant extremely unlikely. The coolant

loops are designed to allow for cooling through natural convection,

meaning that in the case of a power loss or unexpected reactor

shutdown, the heat from the reactor core would be sufficient to keep the

coolant circulating even if the primary cooling pumps were to fail.

The IFR also has passive safety advantages as compared with conventional LWRs. The fuel and cladding

are designed such that when they expand due to increased temperatures,

more neutrons would be able to escape the core, thus reducing the rate

of the fission chain reaction. In other words, an increase in the core

temperature will act as a feedback mechanism that decreases the core

power. This attribute is known as a negative temperature coefficient of reactivity.

Most LWRs also have negative reactivity coefficients; however, in an

IFR, this effect is strong enough to stop the reactor from reaching core

damage without external action from operators or safety systems. This

was demonstrated in a series of safety tests on the prototype. Pete

Planchon, the engineer who conducted the tests for an international

audience quipped "Back in 1986, we actually gave a small [20 MWe]

prototype advanced fast reactor a couple of chances to melt down. It

politely refused both times."

Liquid sodium presents safety problems because it ignites

spontaneously on contact with air and can cause explosions on contact

with water. This was the case at the Monju Nuclear Power Plant

in a 1995 accident and fire. To reduce the risk of explosions following

a leak of water from the steam turbines, the IFR design (as with other sodium-cooled fast reactors)

includes an intermediate liquid-metal coolant loop between the reactor

and the steam turbines. The purpose of this loop is to ensure that any

explosion following accidental mixing of sodium and turbine water would

be limited to the secondary heat exchanger and not pose a risk to the

reactor itself. Alternative designs use lead instead of sodium as the

primary coolant. The disadvantages of lead are its higher density and

viscosity, which increases pumping costs, and radioactive activation

products resulting from neutron absorption. A lead-bismuth eutectate,

as used in some Russian submarine reactors, has lower viscosity and

density, but the same activation product problems can occur.

Efficiency and fuel cycle

| Prop: Unit: |

t½ (a) |

Yield (%) |

Q * (keV) |

βγ * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 155Eu | 4.76 | 0.0803 | 252 | βγ |

| 85Kr | 10.76 | 0.2180 | 687 | βγ |

| 113mCd | 14.1 | 0.0008 | 316 | β |

| 90Sr | 28.9 | 4.505 | 2826 | β |

| 137Cs | 30.23 | 6.337 | 1176 | βγ |

| 121mSn | 43.9 | 0.00005 | 390 | βγ |

| 151Sm | 88.8 | 0.5314 | 77 | β |

The goals of the IFR project were to increase the efficiency of uranium usage by breeding plutonium and eliminating the need for transuranic isotopes ever to leave the site. The reactor was an unmoderated design running on fast neutrons, designed to allow any transuranic isotope to be consumed (and in some cases used as fuel).

Compared to current light-water reactors with a once-through fuel

cycle that induces fission (and derives energy) from less than 1% of

the uranium found in nature, a breeder reactor like the IFR has a very

efficient (99.5% of uranium undergoes fission) fuel cycle.

The basic scheme used pyroelectric separation, a common method in other

metallurgical processes, to remove transuranics and actinides from the

wastes and concentrate them. These concentrated fuels were then

reformed, on site, into new fuel elements.

The available fuel metals were never separated from the plutonium isotopes nor from all the fission products,

and therefore relatively difficult to use in nuclear weapons. Also,

plutonium never had to leave the site, and thus was far less open to

unauthorized diversion.

Another important benefit of removing the long half-life transuranics from the waste cycle is that the remaining waste becomes a much shorter-term hazard. After the actinides (reprocessed uranium, plutonium, and minor actinides) are recycled, the remaining radioactive waste isotopes are fission products, with half-life of 90 years (Sm-151) or less or 211,100 years (Tc-99) and more; plus any activation products from the non-fuel reactor components.

Comparisons to light-water reactors

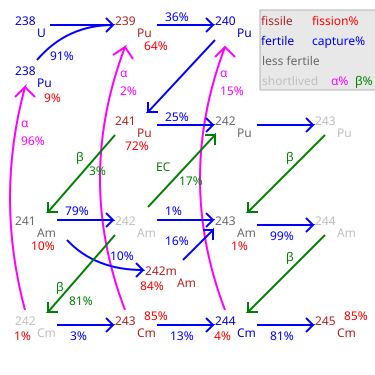

Buildup of heavy actinides in current thermal-neutron fission reactors,

which cannot fission actinide nuclides that have an even number of

neutrons, and thus these build up and are generally treated as Transuranic waste after conventional reprocessing. An argument for fast reactors is that they can fission all actinides.

Nuclear waste

IFR-style reactors produce much less waste than LWR-style reactors, and can even utilize other waste as fuel.

The primary argument for pursuing IFR-style technology today is

that it provides the best solution to the existing nuclear waste problem

because fast reactors can be fueled from the waste products of existing

reactors as well as from the plutonium used in weapons, as is the case

in the operating, as of 2014, BN-800 reactor. Depleted uranium (DU) waste can also be used as fuel in fast reactors.

The waste products of IFR reactors either have a short half-life,

which means that they decay quickly and become relatively safe, or a

long halflife, which means that they are only slightly radioactive. Due

to pyroprocessing the total volume of true waste/fission products

is 1/20th the volume of spent fuel produced by a light water plant of

the same power output, and is often all considered to be waste. 70% of

fission products are either stable or have half lives under one year.

Technetium-99 and iodine-129, which constitute 6% of fission products,

have very long half lives but can be transmuted

to isotopes with very short half lives (15.46 seconds and 12.36 hours)

by neutron absorption within a reactor, effectively destroying them (see

more Long-lived fission products).

Zirconium-93, another 5% of fission products, could in principle be

recycled into fuel-pin cladding, where it does not matter that it is

radioactive. Excluding the contribution from Transuranic waste (TRU) - which are isotopes produced when U-238 captures a slow thermal neutron in a LWR but does not fission, all the remaining high level waste/fission products("FP") left over from reprocessing out the TRU fuel, is less radiotoxic (in Sieverts) than natural uranium (in a gram to gram comparison) within 400 years, and it continues its decline following this.

Edwin Sayre has estimated that a ton of fission products(which also include the very weakly radioactive Palladium-107 etc.) reduced to metal, has a market value of $16 million.

The two forms of IFR waste produced, contain no plutonium or other actinides. The radioactivity of the waste decays to levels similar to the original ore in about 300–400 years.

The on-site reprocessing of fuel means that the volume of high

level nuclear waste leaving the plant is tiny compared to LWR spent

fuel.

In fact, in the U.S. most spent LWR fuel has remained in storage at the

reactor site instead of being transported for reprocessing or placement

in a geological repository. The smaller volumes of high level waste from reprocessing could stay at reactor sites for some time, but are intensely radioactive from medium-lived fission products (MLFPs) and need to be stored securely, like in the present Dry cask storage vessels. In its first few decades of use, before the MLFP's decay to lower heat producing levels, geological repository capacity is constrained not by volume but by heat generation, and decay heat generation from medium-lived fission products is about the same per unit power from any kind of fission reactor, limiting early repository emplacement.

The potential complete removal of plutonium from the waste stream

of the reactor reduces the concern that presently exists with spent

nuclear fuel from most other reactors that arises with burying or

storing their spent fuel in a geological repository, as they could

possibly be used as a plutonium mine at some future date. "Despite the million-fold reduction in radiotoxicity offered by this scheme, some believe that actinide removal would offer few if any significant advantages for disposal in a geologic repository because some of the fission product nuclides of greatest concern in scenarios such as groundwater leaching

actually have longer half-lives than the radioactive actinides. These

concerns do not consider the plan to store such materials in insoluble Synroc,

and do not measure hazards in proportion to those from natural sources

such as medical x-rays, cosmic rays, or natural radioactive rocks (such

as granite). These persons are concerned with radioactive fission products such as technetium-99, iodine-129, and cesium-135 with half-lives between 213,000 and 15.7 million years" Some of which are being targeted for transmutation to belay even these comparatively low concerns, for example the IFR's positive void coefficient could be reduced to an acceptable level by adding technetium to the core, helping destroy the long-lived fission product technetium-99 by nuclear transmutation in the process.

Efficiency

IFRs

use virtually all of the energy content in the uranium fuel whereas a

traditional light water reactor uses less than 0.65% of the energy in

mined uranium, and less than 5% of the energy in enriched uranium.

Carbon dioxide

Both IFRs and LWRs do not emit CO2 during operation, although construction and fuel processing result in CO2 emissions, if energy sources which are not carbon neutral (such as fossil fuels), or CO2 emitting cements are used during the construction process.

A 2012 Yale University review published in the Journal of Industrial Ecology analyzing CO2 life cycle assessment emissions from nuclear power determined that:

The collective LCA literature indicates that life cycle GHG [ greenhouse gas ] emissions from nuclear power are only a fraction of traditional fossil sources and comparable to renewable technologies.

Although the paper primarily dealt with data from Generation II reactors, and did not analyze the CO2 emissions by 2050 of the presently under construction Generation III reactors, it did summarize the Life Cycle Assessment findings of in development reactor technologies.

Theoretical FBRs [ Fast Breeder Reactors ] have been evaluated in the LCA literature. The limited literature that evaluates this potential future technology reports median life cycle GHG emissions... similar to or lower than LWRs[ light water reactors ] and purports to consume little or no uranium ore.

Actinides and fission products by half-life

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinides by decay chain | Half-life range (y) |

Fission products of 235U by yield | ||||||

| 4n | 4n+1 | 4n+2 | 4n+3 | |||||

|

|

4.5–7% | 0.04–1.25% | <0 .001="" span=""> | |||||

| 228Ra№ |

|

|

|

4–6 | † |

|

155Euþ |

|

| 244Cmƒ | 241Puƒ | 250Cf | 227Ac№ | 10–29 | 90Sr | 85Kr | 113mCdþ | |

| 232Uƒ |

|

238Puƒ | 243Cmƒ | 29–97 | 137Cs | 151Smþ | 121mSn | |

| 248Bk[20] | 249Cfƒ | 242mAmƒ |

|

141–351 |

No fission products have a half-life in the range of 100–210 k years ... | |||

|

|

241Amƒ |

|

251Cfƒ | 430–900 | ||||

|

|

|

226Ra№ | 247Bk | 1.3 k – 1.6 k | ||||

| 240Pu | 229Th | 246Cmƒ | 243Amƒ | 4.7 k – 7.4 k | ||||

|

|

245Cmƒ | 250Cm |

|

8.3 k – 8.5 k | ||||

|

|

|

|

239Puƒ | 24.1 k | ||||

|

|

|

230Th№ | 231Pa№ | 32 k – 76 k | ||||

| 236Npƒ | 233Uƒ | 234U№ |

|

150 k – 250 k | ‡ | 99Tc₡ | 126Sn | |

| 248Cm |

|

242Pu |

|

327 k – 375 k |

|

79Se₡ | ||

|

|

|

|

|

1.53 M | 93Zr | |||

|

|

237Npƒ |

|

|

2.1 M – 6.5 M | 135Cs₡ | 107Pd | ||

| 236U |

|

|

247Cmƒ | 15 M – 24 M |

|

129I₡ | ||

| 244Pu№ |

|

|

|

80 M |

... nor beyond 15.7 M years

| |||

| 232Th№ | 238U№ | 235Uƒ№ | 0.7 G – 14.1 G | |||||

|

Legend for superscript symbols ₡ has thermal neutron capture cross section in the range of 8–50 barns ƒ fissile m metastable isomer № primarily a naturally occurring radioactive material (NORM) þ neutron poison (thermal neutron capture cross section greater than 3k barns) † range 4–97 y: Medium-lived fission product ‡ over 200,000 y: Long-lived fission product | ||||||||

Fuel cycle

Fast reactor fuel must be at least 20% fissile, greater than the low enriched uranium used in LWRs.

The fissile material could initially include highly enriched uranium or plutonium, from LWR spent fuel, decommissioned nuclear weapons, or other sources. During operation the reactor breeds more fissile material from fertile material, at most about 5% more from uranium, and 1% more from thorium.

The fertile material in fast reactor fuel can be depleted uranium (mostly U-238), natural uranium, thorium, or reprocessed uranium from spent fuel from traditional light water reactors, and even include nonfissile isotopes of plutonium and minor actinide

isotopes.

Assuming no leakage of actinides to the waste stream during

reprocessing, a 1GWe IFR-style reactor would consume about 1 ton of

fertile material per year and produce about 1 ton of fission products.

The IFR fuel cycle's reprocessing by pyroprocessing (in this case, electrorefining) does not need to produce pure plutonium free of fission product radioactivity as the PUREX

process is designed to do. The purpose of reprocessing in the IFR fuel

cycle is simply to reduce the level of those fission products that are neutron poisons;

even those need not be completely removed.

The electrorefined spent fuel is highly radioactive, but because new

fuel need not be precisely fabricated like LWR fuel pellets but can

simply be cast, remote fabrication can be used, reducing exposure to

workers.

Like any fast reactor, by changing the material used in the

blankets, the IFR can be operated over a spectrum from breeder to

self-sufficient to burner. In breeder mode (using U-238

blankets) it will produce more fissile material than it consumes. This

is useful for providing fissile material for starting up other plants.

Using steel reflectors instead of U-238 blankets, the reactor operates

in pure burner mode and is not a net creator of fissile material; on

balance it will consume fissile and fertile material and, assuming

loss-free reprocessing, output no actinides but only fission products and activation products.

Amount of fissile material needed could be a limiting factor to very

widespread deployment of fast reactors, if stocks of surplus weapons

plutonium and LWR spent fuel plutonium are not sufficient. To maximize

the rate at which fast reactors can be deployed, they can be operated in

maximum breeding mode.

Because the current cost of enriched uranium

is low compared to the expected cost of large-scale pyroprocessing and

electrorefining equipment and the cost of building a secondary coolant

loop, the higher fuel costs of a thermal reactor over the expected operating lifetime of the plant are offset by increased capital cost.

(Currently in the United States, utilities pay a flat rate of 1/10 of a

cent per kilowatt hour to the Government for disposal of high level

radioactive waste by law under the Nuclear Waste Policy Act.

If this charge were based on the longevity of the waste, closed fuel

cycles might become more financially competitive. As the planned

geological repository in the form of Yucca Mountain

is not going ahead, this fund has collected over the years and

presently $25 billion has piled up on the Government's doorstep for

something they have not delivered, that is, reducing the hazard posed by

the waste.

Reprocessing nuclear fuel using pyroprocessing and

electrorefining has not yet been demonstrated on a commercial scale, so

investing in a large IFR-style plant may be a higher financial risk than a conventional light water reactor.

IFR concept (color), an animation of the pyroprocessing cycle is also available.

IFR concept (Black and White with clearer text)

Passive safety

The

IFR uses metal alloy fuel (uranium/plutonium/zirconium) which is a good

conductor of heat, unlike the LWR's (and even some fast breeder

reactors') uranium oxide

which is a poor conductor of heat and reaches high temperatures at the

center of fuel pellets. The IFR also has a smaller volume of fuel, since

the fissile material is diluted with fertile material by a ratio of 5

or less, compared to about 30 for LWR fuel. The IFR core requires more

heat removal per core volume during operation than the LWR core; but on

the other hand, after a shutdown, there is far less trapped heat that is

still diffusing out and needs to be removed. However, decay heat

generation from short-lived fission products and actinides is

comparable in both cases, starting at a high level and decreasing with

time elapsed after shutdown. The high volume of liquid sodium primary

coolant in the pool configuration is designed to absorb decay heat

without reaching fuel melting temperature. The primary sodium pumps are

designed with flywheels so they will coast down slowly (90 seconds) if

power is removed. This coast-down further aids core cooling upon

shutdown. If the primary cooling loop were to be somehow suddenly

stopped, or if the control rods were suddenly removed, the metal fuel

can melt as accidentally demonstrated in EBR-I, however the melting fuel

is then extruded up the steel fuel cladding tubes and out of the active

core region leading to permanent reactor shutdown and no further

fission heat generation or fuel melting. With metal fuel, the cladding is not breached and no radioactivity is released even in extreme overpower transients.

Self-regulation of the IFR's power level depends mainly on

thermal expansion of the fuel which allows more neutrons to escape,

damping the chain reaction. LWRs have less effect from thermal expansion of fuel (since much of the core is the neutron moderator) but have strong negative feedback from Doppler broadening (which acts on thermal and epithermal neutrons, not fast neutrons) and negative void coefficient

from boiling of the water moderator/coolant; the less dense steam

returns fewer and less-thermalized neutrons to the fuel, which are more

likely to be captured by U-238 than induce fissions. However, the IFR's

positive void coefficient could be reduced to an acceptable level by

adding technetium to the core, helping destroy the long-lived fission product technetium-99 by nuclear transmutation in the process.

IFRs are able to withstand both a loss of flow without SCRAM and loss of heat sink without SCRAM.

In addition to passive shutdown of the reactor, the convection current

generated in the primary coolant system will prevent fuel damage (core

meltdown). These capabilities were demonstrated in the EBR-II. The ultimate goal is that no radioactivity will be released under any circumstance.

The flammability of sodium is a risk to operators. Sodium burns

easily in air, and will ignite spontaneously on contact with water. The

use of an intermediate coolant loop between the reactor and the

turbines minimizes the risk of a sodium fire in the reactor core.

Under neutron bombardment, sodium-24 is produced. This is highly radioactive, emitting an energetic gamma ray of 2.7 MeV

followed by a beta decay to form magnesium-24. Half-life is only 15

hours, so this isotope is not a long-term hazard. Nevertheless, the

presence of sodium-24 further necessitates the use of the intermediate

coolant loop between the reactor and the turbines.

Proliferation

IFRs and Light water reactors (LWRs) both produce reactor grade plutonium, and even at high burnups remains weapons usable, but the IFR fuel cycle has some design features that would make proliferation more difficult than the current PUREX recycling of spent LWR fuel. For one thing, it may operate at higher burnups and therefore increase the relative abundance of the non-fissile, but fertile, isotopes Plutonium-238, Plutonium-240 and Plutonium-242.

Unlike PUREX reprocessing, the IFR's electrolytic reprocessing of spent fuel

did not separate out pure plutonium, and left it mixed with minor

actinides and some rare earth fission products which make the

theoretical ability to make a bomb directly out of it considerably

dubious.

Rather than being transported from a large centralized reprocessing

plant to reactors at other locations, as is common now in France, from La Hague to its dispersed nuclear fleet of LWRs, the IFR pyroprocessed fuel would be much more resistant to unauthorized diversion. The material with the mix of plutonium isotopes in an IFR would stay at the reactor site and then be burnt up practically in-situ,

alternatively, if operated as a breeder reactor, some of the

pyroprocessed fuel could be consumed by the same or other reactors

located elsewhere. However, as is the case with conventional aqueous

reprocessing, it would remain possible to chemically extract all the

plutonium isotopes from the pyroprocessed/recycled fuel and would be

much easier to do so from the recycled product than from the original

spent fuel, although compared to other conventional recycled nuclear

fuel, MOX, it would be more difficult, as the IFR recycled fuel contains more fission products than MOX and due to its higher burnup, more proliferation resistant Pu-240 than MOX.

An advantage of the IFRs actinides removal and burn up (actinides

include plutonium) from its spent fuel, is to eliminate concerns about

leaving the IFRs spent fuel or indeed conventional, and therefore

comparatively lower burnup, spent fuel - which can contain weapons usable plutonium isotope concentrations in a geological repository(or the more common dry cask storage) which then might be mined sometime in the future for the purpose of making weapons."

Because reactor-grade plutonium contains isotopes of plutonium with high spontaneous fission rates, and the ratios of these troublesome isotopes-from a weapons manufacturing point of view, only increases as the fuel is burnt up

for longer and longer, it is considerably more difficult to produce

fission nuclear weapons which will achieve a substantial yield from

higher-burnup spent fuel than from conventional, moderately burnt up, LWR spent fuel.

Therefore, proliferation risks are considerably reduced with the

IFR system by many metrics, but not entirely eliminated. The plutonium

from ALMR recycled fuel would have an isotopic composition similar to that obtained from other high burnt up spent nuclear fuel

sources. Although this makes the material less attractive for weapons

production, it could be used in weapons at varying degrees of

sophistication/with fusion boosting.

The U.S. government detonated a nuclear device in 1962 using then defined "reactor-grade plutonium", although in more recent categorizations it would instead be considered as fuel-grade plutonium, typical of that produced by low burn up magnox reactors.

Plutonium produced in the fuel of a breeder reactor generally has a higher fraction of the isotope plutonium-240, than that produced in other reactors, making it less attractive for weapons use, particularly in first generation nuclear weapon designs similar to Fat Man.

This offers an intrinsic degree of proliferation resistance, but the

plutonium made in the blanket of uranium surrounding the core, if such a

blanket is used, is usually of a high Pu-239 quality, containing very little Pu-240, making it highly attractive for weapons use.

"Although some recent proposals for the future of the ALMR/IFR

concept have focused more on its ability to transform and irreversibly

use up plutonium, such as the conceptual PRISM (reactor) and the in operation(2014) BN-800 reactor

in Russia, the developers of the IFR acknowledge that it is

'uncontested that the IFR can be configured as a net producer of

plutonium'."

As mentioned above, if operated not as a burner, but as a

breeder, the IFR has a clear proliferation potential "if instead of

processing spent fuel, the ALMR system were used to reprocess irradiated fertile (breeding) material

(that is if a blanket of breeding U-238 was used), the resulting

plutonium would be a superior material, with a nearly ideal isotope

composition for nuclear weapons manufacture."

Reactor design and construction

A commercial version of the IFR, S-PRISM, can be built in a factory and transported to the site. This small modular

design (311 MWe modules) reduces costs and allows nuclear plants of

various sizes (311 MWe and any integer multiple) to be economically

constructed.

Cost assessments taking account of the complete life cycle show

that fast reactors could be no more expensive than the most widely used

reactors in the world – water-moderated water-cooled reactors.

Liquid metal Na coolant

Unlike reactors that use relatively slow low energy (thermal) neutrons, fast-neutron reactors need nuclear reactor coolant that does not moderate or block neutrons (like water does in an LWR) so that they have sufficient energy to fission actinide isotopes that are fissionable but not fissile.

The core must also be compact and contain as small amount of material

that might act as neutron moderators as possible. Metal sodium (Na)

coolant in many ways has the most attractive combination of properties

for this purpose. In addition to not being a neutron moderator,

desirable physical characteristics include:

- Low melting temperature

- Low vapor pressure

- High boiling temperature

- Excellent thermal conductivity

- Low viscosity

- Light weight

- Thermal and radiation stability

Other benefits: Abundant and low cost material. Cleaning with chlorine produces

non-toxic table salt. Compatible with other materials used in the core

(does not react or dissolve stainless steel) so no special corrosion

protection measures needed. Low pumping power (from light weight and

low viscosity). Maintains an oxygen (and water) free environment by

reacting with trace amounts to make sodium oxide or sodium hydroxide and

hydrogen, thereby protecting other components from corrosion. Light

weight (low density) improves resistance to seismic inertia events

(earthquakes.)

Drawbacks include: Extreme fire hazard with any significant amounts of air (oxygen)

and spontaneous combustion with water, rendering sodium leaks and

flooding dangerous. This was the case at the Monju Nuclear Power Plant in a 1995 accident and fire. Reactions with water produce hydrogen which can be explosive. Sodium activation product (isotope) 24Na

releases dangerous energetic photons when it decays (however it has a

very short half-life of 15 hours). Reactor design keeps 24Na

in the reactor pool and carries away heat for power production using a

secondary sodium loop, adding costs to construction and maintenance.

History

Research on the reactor began in 1984 at Argonne National Laboratory in Argonne, Illinois. Argonne is a part of the U.S. Department of Energy's national laboratory system, and is operated on a contract by the University of Chicago.

Argonne previously had a branch campus named "Argonne West" in Idaho Falls, Idaho that is now part of the Idaho National Laboratory. In the past, at the branch campus, physicists from Argonne had built what was known as the Experimental Breeder Reactor II

(EBR II). In the mean time, physicists at Argonne had designed the IFR

concept, and it was decided that the EBR II would be converted to an

IFR. Charles Till, a Canadian physicist from Argonne, was the head of

the IFR project, and Yoon Chang was the deputy head. Till was positioned

in Idaho, while Chang was in Illinois.

With the election of President Bill Clinton in 1992, and the appointment of Hazel O'Leary as the Secretary of Energy, there was pressure from the top to cancel the IFR. Sen. John Kerry

(D-MA) and O'Leary led the opposition to the reactor, arguing that it

would be a threat to non-proliferation efforts, and that it was a

continuation of the Clinch River Breeder Reactor Project that had been canceled by Congress.

Simultaneously, in 1994 Energy Secretary O'Leary awarded the lead

IFR scientist with $10,000 and a gold medal, with the citation stating

his work to develop IFR technology provided "improved safety, more

efficient use of fuel and less radioactive waste."

IFR opponents also presented a report

by the DOE's Office of Nuclear Safety regarding a former Argonne

employee's allegations that Argonne had retaliated against him for

raising concerns about safety, as well as about the quality of research

done on the IFR program. The report received international attention,

with a notable difference in the coverage it received from major

scientific publications. The British journal Nature entitled its

article "Report backs whistleblower", and also noted conflicts of

interest on the part of a DOE panel that assessed IFR research. In contrast, the article that appeared in Science was entitled "Was Argonne Whistleblower Really Blowing Smoke?".

Remarkably, that article did not disclose that the Director of Argonne

National Laboratories, Alan Schriesheim, was a member of the Board of

Directors of Science's parent organization, the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Despite support for the reactor by then-Rep. Richard Durbin (D-IL) and U.S. Senators Carol Moseley Braun (D-IL) and Paul Simon (D-IL), funding for the reactor was slashed, and it was ultimately canceled in 1994 by S.Amdt. 2127 to H.R. 4506,

at greater cost than finishing it. When this was brought to President

Clinton's attention, he said "I know; it's a symbol." By this time

Senator Kerry and the majority of democrats had switched to supporting

the continuation of the program. The final count was to 52 to 46 to

terminate the program, with 36 republicans and 16 democrats voting for

its termination, while just 8 republicans and 38 democrats voted for its

continuation.

In 2001, as part of the Generation IV

roadmap, the DOE tasked a 242-person team of scientists from DOE, UC

Berkeley, MIT, Stanford, ANL, LLNL, Toshiba, Westinghouse, Duke, EPRI,

and other institutions to evaluate 19 of the best reactor designs on 27

different criteria. The IFR ranked #1 in their study which was released

April 9, 2002.

At present there are no Integral Fast Reactors in commercial

operation, however a very similar fast reactor, operated as a burner of

plutonium stockpiles, the BN-800 reactor, became commercially operational in 2014.