1875 geological map of Europe, compiled by the Belgian geologist André Dumont. Colors indicate the distribution of different rock types across the continent, as they were known then.

Geology describes the structure of the Earth beneath its surface, and the processes that have shaped that structure. It also provides tools to determine the relative and absolute ages of rocks found in a given location, and also to describe the histories of those rocks. By combining these tools, geologists are able to chronicle the geological history of the Earth as a whole, and also to demonstrate the age of the Earth. Geology provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and the Earth's past climates.

Geologists use a wide variety of methods to understand the Earth's structure and evolution, including field work, rock description, geophysical techniques, chemical analysis, physical experiments, and numerical modelling. In practical terms, geology is important for mineral and hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation, evaluating water resources, understanding of natural hazards, the remediation of environmental problems, and providing insights into past climate change. Geology, a major academic discipline, also plays a role in geotechnical engineering.

Geologic materials

The

majority of geological data comes from research on solid Earth

materials. These typically fall into one of two categories: rock and

unconsolidated material.

Rock

This schematic diagram of the rock cycle shows the relationship between magma and sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous rock

The majority of research in geology is associated with the study of

rock, as rock provides the primary record of the majority of the

geologic history of the Earth. There are three major types of rock: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic. The rock cycle

illustrates the relationships among them (see diagram).

When a rock crystallizes from melt (magma or lava), it is an igneous rock. This rock can be weathered and eroded, then redeposited and lithified into a sedimentary rock. It can then be turned into a metamorphic rock by heat and pressure that change its mineral content, resulting in a characteristic fabric.

All three types may melt again, and when this happens, new magma is

formed, from which an igneous rock may once more crystallize.

Minerals

Tests

To study

all three types of rock, geologists evaluate the minerals of which they

are composed. Each mineral has distinct physical properties, and there

are many tests to determine each of them. The specimens can be tested

for:

- Luster: Measurement of the amount of light reflected from the surface. Luster is broken into metallic and nonmetallic.

- Color: Minerals are grouped by their color. Mostly diagnostic but impurities can change a mineral’s color.

- Streak: Performed by scratching the sample on a porcelain plate. The color of the streak can help name the mineral.

- Hardness: The resistance of a mineral to scratch.

- Breakage pattern: A mineral can either show fracture or cleavage, the former being breakage of uneven surfaces and the latter a breakage along closely spaced parallel planes.

- Specific gravity: the weight of a specific volume of a mineral.

- Effervescence: Involves dripping hydrochloric acid on the mineral to test for fizzing.

- Magnetism: Involves using a magnet to test for magnetism.

- Taste: Minerals can have a distinctive taste, like halite (which tastes like table salt).

- Smell: Minerals can have a distinctive odor. For example, sulfur smells like rotten eggs.

Unconsolidated material

Geologists also study unlithified materials (referred to as drift), which typically come from more recent deposits. These materials are superficial deposits that lie above the bedrock. This study is often known as Quaternary geology, after the Quaternary period of geologic history.

Whole-Earth structure

Plate tectonics

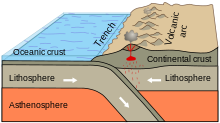

Oceanic-continental convergence resulting in subduction and volcanic arcs illustrates one effect of plate tectonics.

In the 1960s, it was discovered that the Earth's lithosphere, which includes the crust and rigid uppermost portion of the upper mantle, is separated into tectonic plates that move across the plastically deforming, solid, upper mantle, which is called the asthenosphere. This theory is supported by several types of observations, including seafloor spreading and the global distribution of mountain terrain and seismicity.

There is an intimate coupling between the movement of the plates on the surface and the convection of the mantle (that is, the heat transfer caused by bulk movement of molecules within fluids). Thus, oceanic plates and the adjoining mantle convection currents always move in the same direction – because the oceanic lithosphere is actually the rigid upper thermal boundary layer of the convecting mantle. This coupling between rigid plates moving on the surface of the Earth and the convecting mantle is called plate tectonics.

In this diagram, subducting slabs

are in blue and continental margins and a few plate boundaries are in

red. The blue blob in the cutaway section is the seismically imaged Farallon Plate, which is subducting beneath North America. The remnants of this plate on the surface of the Earth are the Juan de Fuca Plate and Explorer Plate, both in the northwestern United States and southwestern Canada, and the Cocos Plate on the west coast of Mexico.

The development of plate tectonics has provided a physical basis for

many observations of the solid Earth. Long linear regions of geologic

features are explained as plate boundaries. For example:

- Mid-ocean ridges, high regions on the seafloor where hydrothermal vents and volcanoes exist, are seen as divergent boundaries, where two plates move apart.

- Arcs of volcanoes and earthquakes are theorized as convergent boundaries, where one plate subducts, or moves, under another.

Transform boundaries, such as the San Andreas Fault system, resulted in widespread powerful earthquakes. Plate tectonics also has provided a mechanism for Alfred Wegener's theory of continental drift, in which the continents

move across the surface of the Earth over geologic time. They also

provided a driving force for crustal deformation, and a new setting for

the observations of structural geology. The power of the theory of plate

tectonics lies in its ability to combine all of these observations into

a single theory of how the lithosphere moves over the convecting

mantle.

Earth structure

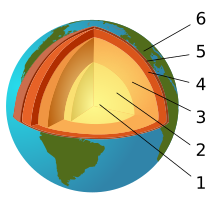

The Earth's

layered structure. (1) inner core; (2) outer core; (3) lower mantle;

(4) upper mantle; (5) lithosphere; (6) crust (part of the lithosphere)

Earth

layered structure. Typical wave paths from earthquakes like these gave

early seismologists insights into the layered structure of the Earth

Advances in seismology, computer modeling, and mineralogy and crystallography at high temperatures and pressures give insights into the internal composition and structure of the Earth.

Seismologists can use the arrival times of seismic waves in reverse to image the interior of the Earth. Early advances in this field showed the existence of a liquid outer core (where shear waves were not able to propagate) and a dense solid inner core. These advances led to the development of a layered model of the Earth, with a crust and lithosphere on top, the mantle below (separated within itself by seismic discontinuities

at 410 and 660 kilometers), and the outer core and inner core below

that. More recently, seismologists have been able to create detailed

images of wave speeds inside the earth in the same way a doctor images a

body in a CT scan. These images have led to a much more detailed view

of the interior of the Earth, and have replaced the simplified layered

model with a much more dynamic model.

Mineralogists have been able to use the pressure and temperature

data from the seismic and modelling studies alongside knowledge of the

elemental composition of the Earth to reproduce these conditions in

experimental settings and measure changes in crystal structure. These

studies explain the chemical changes associated with the major seismic

discontinuities in the mantle and show the crystallographic structures

expected in the inner core of the Earth.

Geologic time

The geologic time scale encompasses the history of the Earth. It is bracketed at the earliest by the dates of the first Solar System material at 4.567 Ga (or 4.567 billion years ago) and the formation of the Earth at

4.54 Ga

(4.54 billion years), which is the beginning of the informally recognized Hadean eon – a division of geologic time. At the later end of the scale, it is marked by the present day (in the Holocene epoch).

Time scale

The

following four timelines show the geologic time scale. The first shows

the entire time from the formation of the Earth to the present, but this

gives little space for the most recent eon. Therefore, the second

timeline shows an expanded view of the most recent eon. In a similar

way, the most recent era is expanded in the third timeline, and the most

recent period is expanded in the fourth timeline.

Important milestones

Geological time put in a diagram called a geological clock, showing the relative lengths of the eons of the Earth's history.

- 4.567 Ga (gigaannum: billion years ago): Solar system formation

- 4.54 Ga: Accretion, or formation, of Earth

- c. 4 Ga: End of Late Heavy Bombardment, first life

- c. 3.5 Ga: Start of photosynthesis

- c. 2.3 Ga: Oxygenated atmosphere, first snowball Earth

- 730–635 Ma (megaannum: million years ago): second snowball Earth

- 542 ± 0.3 Ma: Cambrian explosion – vast multiplication of hard-bodied life; first abundant fossils; start of the Paleozoic

- c. 380 Ma: First vertebrate land animals

- 250 Ma: Permian-Triassic extinction – 90% of all land animals die; end of Paleozoic and beginning of Mesozoic

- 66 Ma: Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction – Dinosaurs die; end of Mesozoic and beginning of Cenozoic

- c. 7 Ma: First hominins appear

- 3.9 Ma: First Australopithecus, direct ancestor to modern Homo sapiens, appear

- 200 ka (kiloannum: thousand years ago): First modern Homo sapiens appear in East Africa

Dating methods

Relative dating

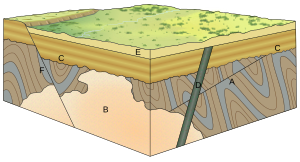

Cross-cutting relations can be used to determine the relative ages of rock strata and other geological structures. Explanations: A – folded rock strata cut by a thrust fault; B – large intrusion (cutting through A); C – erosional angular unconformity (cutting off A & B) on which rock strata were deposited; D – volcanic dyke (cutting through A, B & C); E – even younger rock strata (overlying C & D); F – normal fault (cutting through A, B, C & E).

Methods for relative dating were developed when geology first emerged as a natural science.

Geologists still use the following principles today as a means to

provide information about geologic history and the timing of geologic

events.

The principle of uniformitarianism

states that the geologic processes observed in operation that modify

the Earth's crust at present have worked in much the same way over

geologic time. A fundamental principle of geology advanced by the 18th century Scottish physician and geologist James Hutton

is that "the present is the key to the past." In Hutton's words: "the

past history of our globe must be explained by what can be seen to be

happening now."

The principle of intrusive relationships concerns crosscutting intrusions. In geology, when an igneous intrusion cuts across a formation of sedimentary rock,

it can be determined that the igneous intrusion is younger than the

sedimentary rock. Different types of intrusions include stocks, laccoliths, batholiths, sills and dikes.

The principle of cross-cutting relationships pertains to the formation of faults

and the age of the sequences through which they cut. Faults are younger

than the rocks they cut; accordingly, if a fault is found that

penetrates some formations but not those on top of it, then the

formations that were cut are older than the fault, and the ones that are

not cut must be younger than the fault. Finding the key bed in these

situations may help determine whether the fault is a normal fault or a thrust fault.

The principle of inclusions and components states that, with sedimentary rocks, if inclusions (or clasts)

are found in a formation, then the inclusions must be older than the

formation that contains them. For example, in sedimentary rocks, it is

common for gravel from an older formation to be ripped up and included

in a newer layer. A similar situation with igneous rocks occurs when xenoliths are found. These foreign bodies are picked up as magma

or lava flows, and are incorporated, later to cool in the matrix. As a

result, xenoliths are older than the rock that contains them.

The Permian through Jurassic stratigraphy of the Colorado Plateau area of southeastern Utah

is an example of both original horizontality and the law of

superposition. These strata make up much of the famous prominent rock

formations in widely spaced protected areas such as Capitol Reef National Park and Canyonlands National Park. From top to bottom: Rounded tan domes of the Navajo Sandstone, layered red Kayenta Formation, cliff-forming, vertically jointed, red Wingate Sandstone, slope-forming, purplish Chinle Formation, layered, lighter-red Moenkopi Formation, and white, layered Cutler Formation sandstone. Picture from Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

The principle of original horizontality

states that the deposition of sediments occurs as essentially

horizontal beds. Observation of modern marine and non-marine sediments

in a wide variety of environments supports this generalization (although

cross-bedding is inclined, the overall orientation of cross-bedded units is horizontal).

The principle of superposition states that a sedimentary rock layer in a tectonically

undisturbed sequence is younger than the one beneath it and older than

the one above it. Logically a younger layer cannot slip beneath a layer

previously deposited. This principle allows sedimentary layers to be

viewed as a form of vertical time line, a partial or complete record of

the time elapsed from deposition of the lowest layer to deposition of

the highest bed.

The principle of faunal succession

is based on the appearance of fossils in sedimentary rocks. As

organisms exist during the same period throughout the world, their

presence or (sometimes) absence provides a relative age of the

formations where they appear. Based on principles that William Smith

laid out almost a hundred years before the publication of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution,

the principles of succession developed independently of evolutionary

thought. The principle becomes quite complex, however, given the

uncertainties of fossilization, localization of fossil types due to

lateral changes in habitat (facies change in sedimentary strata), and that not all fossils formed globally at the same time.

Absolute dating

Geologists also use methods to determine the absolute age of rock

samples and geological events. These dates are useful on their own and

may also be used in conjunction with relative dating methods or to

calibrate relative methods.

At the beginning of the 20th century, advancement in geological

science was facilitated by the ability to obtain accurate absolute dates

to geologic events using radioactive isotopes

and other methods. This changed the understanding of geologic time.

Previously, geologists could only use fossils and stratigraphic

correlation to date sections of rock relative to one another. With

isotopic dates, it became possible to assign absolute ages

to rock units, and these absolute dates could be applied to fossil

sequences in which there was datable material, converting the old

relative ages into new absolute ages.

For many geologic applications, isotope ratios

of radioactive elements are measured in minerals that give the amount

of time that has passed since a rock passed through its particular closure temperature, the point at which different radiometric isotopes stop diffusing into and out of the crystal lattice. These are used in geochronologic and thermochronologic studies. Common methods include uranium-lead dating, potassium-argon dating, argon-argon dating and uranium-thorium dating. These methods are used for a variety of applications. Dating of lava and volcanic ash

layers found within a stratigraphic sequence can provide absolute age

data for sedimentary rock units that do not contain radioactive isotopes

and calibrate relative dating techniques. These methods can also be

used to determine ages of pluton

emplacement.

Thermochemical techniques can be used to determine temperature profiles

within the crust, the uplift of mountain ranges, and paleotopography.

Fractionation of the lanthanide series elements is used to compute ages since rocks were removed from the mantle.

Other methods are used for more recent events. Optically stimulated luminescence and cosmogenic radionuclide dating are used to date surfaces and/or erosion rates. Dendrochronology can also be used for the dating of landscapes. Radiocarbon dating is used for geologically young materials containing organic carbon.

Geological development of an area

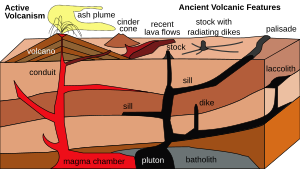

An originally horizontal sequence of sedimentary rocks (in shades of tan) are affected by igneous activity. Deep below the surface are a magma chamber and large associated igneous bodies. The magma chamber feeds the volcano, and sends offshoots of magma that will later crystallize into dikes and sills. Magma also advances upwards to form intrusive igneous bodies. The diagram illustrates both a cinder cone volcano, which releases ash, and a composite volcano, which releases both lava and ash.

An illustration of the three types of faults.

A. Strike-slip faults occur when rock units slide past one another.

B. Normal faults occur when rocks are undergoing horizontal extension.

C. Reverse (or thrust) faults occur when rocks are undergoing horizontal shortening.

A. Strike-slip faults occur when rock units slide past one another.

B. Normal faults occur when rocks are undergoing horizontal extension.

C. Reverse (or thrust) faults occur when rocks are undergoing horizontal shortening.

The geology of an area changes through time as rock units are

deposited and inserted, and deformational processes change their shapes

and locations.

Rock units are first emplaced either by deposition onto the surface or intrusion into the overlying rock. Deposition can occur when sediments settle onto the surface of the Earth and later lithify into sedimentary rock, or when as volcanic material such as volcanic ash or lava flows blanket the surface. Igneous intrusions such as batholiths, laccoliths, dikes, and sills, push upwards into the overlying rock, and crystallize as they intrude.

After the initial sequence of rocks has been deposited, the rock units can be deformed and/or metamorphosed. Deformation typically occurs as a result of horizontal shortening, horizontal extension, or side-to-side (strike-slip) motion. These structural regimes broadly relate to convergent boundaries, divergent boundaries, and transform boundaries, respectively, between tectonic plates.

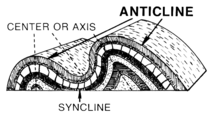

When rock units are placed under horizontal compression, they shorten and become thicker. Because rock units, other than muds, do not significantly change in volume, this is accomplished in two primary ways: through faulting and folding. In the shallow crust, where brittle deformation

can occur, thrust faults form, which causes deeper rock to move on top

of shallower rock. Because deeper rock is often older, as noted by the principle of superposition,

this can result in older rocks moving on top of younger ones. Movement

along faults can result in folding, either because the faults are not

planar or because rock layers are dragged along, forming drag folds as

slip occurs along the fault. Deeper in the Earth, rocks behave

plastically and fold instead of faulting. These folds can either be

those where the material in the center of the fold buckles upwards,

creating "antiforms", or where it buckles downwards, creating "synforms". If the tops of the rock units within the folds remain pointing upwards, they are called anticlines and synclines,

respectively. If some of the units in the fold are facing downward, the

structure is called an overturned anticline or syncline, and if all of

the rock units are overturned or the correct up-direction is unknown,

they are simply called by the most general terms, antiforms and

synforms.

Even higher pressures and temperatures during horizontal shortening can cause both folding and metamorphism of the rocks. This metamorphism causes changes in the mineral composition of the rocks; creates a foliation,

or planar surface, that is related to mineral growth under stress.

This can remove signs of the original textures of the rocks, such as bedding in sedimentary rocks, flow features of lavas, and crystal patterns in crystalline rocks.

Extension causes the rock units as a whole to become longer and thinner. This is primarily accomplished through normal faulting

and through the ductile stretching and thinning. Normal faults drop

rock units that are higher below those that are lower. This typically

results in younger units ending up below older units. Stretching of

units can result in their thinning. In fact, at one location within the Maria Fold and Thrust Belt, the entire sedimentary sequence of the Grand Canyon

appears over a length of less than a meter. Rocks at the depth to be

ductilely stretched are often also metamorphosed. These stretched rocks

can also pinch into lenses, known as boudins, after the French word for "sausage" because of their visual similarity.

Where rock units slide past one another, strike-slip faults develop in shallow regions, and become shear zones at deeper depths where the rocks deform ductilely.

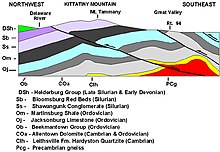

Geologic cross section of Kittatinny Mountain.

This cross section shows metamorphic rocks, overlain by younger

sediments deposited after the metamorphic event. These rock units were

later folded and faulted during the uplift of the mountain.

The addition of new rock units, both depositionally and intrusively,

often occurs during deformation. Faulting and other deformational

processes result in the creation of topographic gradients, causing

material on the rock unit that is increasing in elevation to be eroded

by hillslopes and channels. These sediments are deposited on the rock

unit that is going down. Continual motion along the fault maintains the

topographic gradient in spite of the movement of sediment, and continues

to create accommodation space

for the material to deposit. Deformational events are often also

associated with volcanism and igneous activity. Volcanic ashes and lavas

accumulate on the surface, and igneous intrusions enter from below. Dikes,

long, planar igneous intrusions, enter along cracks, and therefore

often form in large numbers in areas that are being actively deformed.

This can result in the emplacement of dike swarms, such as those that are observable across the Canadian shield, or rings of dikes around the lava tube of a volcano.

All of these processes do not necessarily occur in a single environment, and do not necessarily occur in a single order. The Hawaiian Islands, for example, consist almost entirely of layered basaltic lava flows. The sedimentary sequences of the mid-continental United States and the Grand Canyon in the southwestern United States contain almost-undeformed stacks of sedimentary rocks that have remained in place since Cambrian

time. Other areas are much more geologically complex. In the

southwestern United States, sedimentary, volcanic, and intrusive rocks

have been metamorphosed, faulted, foliated, and folded. Even older

rocks, such as the Acasta gneiss of the Slave craton in northwestern Canada, the oldest known rock in the world

have been metamorphosed to the point where their origin is

undiscernable without laboratory analysis. In addition, these processes

can occur in stages. In many places, the Grand Canyon in the

southwestern United States being a very visible example, the lower rock

units were metamorphosed and deformed, and then deformation ended and

the upper, undeformed units were deposited. Although any amount of rock

emplacement and rock deformation can occur, and they can occur any

number of times, these concepts provide a guide to understanding the geological history of an area.

Methods of geology

Geologists

use a number of field, laboratory, and numerical modeling methods to

decipher Earth history and to understand the processes that occur on and

inside the Earth. In typical geological investigations, geologists use

primary information related to petrology

(the study of rocks), stratigraphy (the study of sedimentary layers),

and structural geology (the study of positions of rock units and their

deformation). In many cases, geologists also study modern soils, rivers, landscapes, and glaciers; investigate past and current life and biogeochemical pathways, and use geophysical methods to investigate the subsurface. Sub-specialities of geology may distinguish endogenous and exogenous geology.

Field methods

A standard Brunton Pocket Transit, commonly used by geologists for mapping and surveying.

A typical USGS field mapping camp in the 1950s

Today, handheld computers with GPS and geographic information systems software are often used in geological field work (digital geologic mapping).

Geological field work varies depending on the task at hand. Typical fieldwork could consist of:

- Geological mapping

- Structural mapping: identifying the locations of major rock units and the faults and folds that led to their placement there.

- Stratigraphic mapping: pinpointing the locations of sedimentary facies (lithofacies and biofacies) or the mapping of isopachs of equal thickness of sedimentary rock

- Surficial mapping: recording the locations of soils and surficial deposits

- Surveying of topographic features

- compilation of topographic maps

- Work to understand change across landscapes, including:

- Patterns of erosion and deposition

- River-channel change through migration and avulsion

- Hillslope processes

- Subsurface mapping through geophysical methods

- These methods include:

- They aid in:

- High-resolution stratigraphy

- Measuring and describing stratigraphic sections on the surface

- Well drilling and logging

- Biogeochemistry and geomicrobiology

- Collecting samples to:

- determine biochemical pathways

- identify new species of organisms

- identify new chemical compounds

- and to use these discoveries to:

- understand early life on Earth and how it functioned and metabolized

- find important compounds for use in pharmaceuticals

- Collecting samples to:

- Paleontology: excavation of fossil material

- Collection of samples for geochronology and thermochronology

- Glaciology: measurement of characteristics of glaciers and their motion

Petrology

A petrographic microscope – an optical microscope fitted with cross-polarizing lenses, a conoscopic lens, and compensators (plates of anisotropic materials; gypsum plates and quartz wedges are common), for crystallographic analysis.

In addition to identifying rocks in the field (lithology),

petrologists identify rock samples in the laboratory. Two of the

primary methods for identifying rocks in the laboratory are through optical microscopy and by using an electron microprobe. In an optical mineralogy analysis, petrologists analyze thin sections of rock samples using a petrographic microscope,

where the minerals can be identified through their different properties

in plane-polarized and cross-polarized light, including their birefringence, pleochroism, twinning, and interference properties with a conoscopic lens.

In the electron microprobe, individual locations are analyzed for their

exact chemical compositions and variation in composition within

individual crystals. Stable and radioactive isotope studies provide insight into the geochemical evolution of rock units.

Petrologists can also use fluid inclusion data and perform high temperature and pressure physical experiments to understand the temperatures and pressures at which different mineral phases appear, and how they change through igneous

and metamorphic processes. This research can be extrapolated to the

field to understand metamorphic processes and the conditions of

crystallization of igneous rocks. This work can also help to explain processes that occur within the Earth, such as subduction and magma chamber evolution.

Structural geology

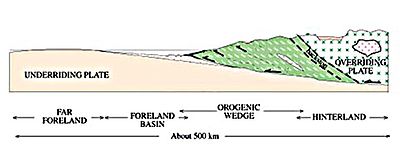

A diagram of an orogenic wedge. The wedge grows through faulting in the interior and along the main basal fault, called the décollement. It builds its shape into a critical taper,

in which the angles within the wedge remain the same as failures inside

the material balance failures along the décollement. It is analogous to

a bulldozer pushing a pile of dirt, where the bulldozer is the

overriding plate.

Structural geologists use microscopic analysis of oriented thin sections of geologic samples to observe the fabric

within the rocks, which gives information about strain within the

crystalline structure of the rocks. They also plot and combine

measurements of geological structures to better understand the

orientations of faults and folds to reconstruct the history of rock

deformation in the area. In addition, they perform analog and numerical experiments of rock deformation in large and small settings.

The analysis of structures is often accomplished by plotting the orientations of various features onto stereonets.

A stereonet is a stereographic projection of a sphere onto a plane, in

which planes are projected as lines and lines are projected as points.

These can be used to find the locations of fold axes, relationships

between faults, and relationships between other geologic structures.

Among the most well-known experiments in structural geology are those involving orogenic wedges, which are zones in which mountains are built along convergent tectonic plate boundaries.

In the analog versions of these experiments, horizontal layers of sand

are pulled along a lower surface into a back stop, which results in

realistic-looking patterns of faulting and the growth of a critically tapered (all angles remain the same) orogenic wedge.

Numerical models work in the same way as these analog models, though

they are often more sophisticated and can include patterns of erosion

and uplift in the mountain belt.

This helps to show the relationship between erosion and the shape of a

mountain range. These studies can also give useful information about

pathways for metamorphism through pressure, temperature, space, and

time.

Stratigraphy

Different colours shows the different minerals composing the mount Ritagli di Lecca seen from Fondachelli-Fantina, Sicily

In the laboratory, stratigraphers analyze samples of stratigraphic

sections that can be returned from the field, such as those from drill cores. Stratigraphers also analyze data from geophysical surveys that show the locations of stratigraphic units in the subsurface. Geophysical data and well logs

can be combined to produce a better view of the subsurface, and

stratigraphers often use computer programs to do this in three

dimensions. Stratigraphers can then use these data to reconstruct ancient processes occurring on the surface of the Earth, interpret past environments, and locate areas for water, coal, and hydrocarbon extraction.

In the laboratory, biostratigraphers analyze rock samples from outcrop and drill cores for the fossils found in them. These fossils help scientists to date the core and to understand the depositional environment

in which the rock units formed. Geochronologists precisely date rocks

within the stratigraphic section to provide better absolute bounds on

the timing and rates of deposition.

Magnetic stratigraphers look for signs of magnetic reversals in igneous rock units within the drill cores. Other scientists perform stable-isotope studies on the rocks to gain information about past climate.

Planetary geology

Surface of Mars as photographed by the Viking 2 lander December 9, 1977.

With the advent of space exploration

in the twentieth century, geologists have begun to look at other

planetary bodies in the same ways that have been developed to study the Earth. This new field of study is called planetary geology (sometimes known as astrogeology) and relies on known geologic principles to study other bodies of the solar system.

Although the Greek-language-origin prefix geo

refers to Earth, "geology" is often used in conjunction with the names

of other planetary bodies when describing their composition and internal

processes: examples are "the geology of Mars" and "Lunar geology". Specialised terms such as selenology (studies of the Moon), areology (of Mars), etc., are also in use.

Although planetary geologists are interested in studying all

aspects of other planets, a significant focus is to search for evidence

of past or present life on other worlds. This has led to many missions

whose primary or ancillary purpose is to examine planetary bodies for

evidence of life. One of these is the Phoenix lander, which analyzed Martian polar soil for water, chemical, and mineralogical constituents related to biological processes.

Applied geology

Economic geology

Economic geology is a branch of geology that deals with aspects of

economic minerals that humankind uses to fulfill various needs. Economic

minerals are those extracted profitably for various practical uses.

Economic geologists help locate and manage the Earth's natural resources, such as petroleum and coal, as well as mineral resources, which include metals such as iron, copper, and uranium.

Mining geology

Mining geology consists of the extractions of mineral resources from the Earth. Some resources of economic interests include gemstones, metals such as gold and copper, and many minerals such as asbestos, perlite, mica, phosphates, zeolites, clay, pumice, quartz, and silica, as well as elements such as sulfur, chlorine, and helium.

Petroleum geology

Mud log in process, a common way to study the lithology when drilling oil wells.

Petroleum geologists study the locations of the subsurface of the Earth that can contain extractable hydrocarbons, especially petroleum and natural gas. Because many of these reservoirs are found in sedimentary basins,

they study the formation of these basins, as well as their sedimentary

and tectonic evolution and the present-day positions of the rock units.

Engineering geology

Engineering geology is the application of the geologic principles to

engineering practice for the purpose of assuring that the geologic

factors affecting the location, design, construction, operation, and

maintenance of engineering works are properly addressed.

In the field of civil engineering,

geological principles and analyses are used in order to ascertain the

mechanical principles of the material on which structures are built.

This allows tunnels to be built without collapsing, bridges and

skyscrapers to be built with sturdy foundations, and buildings to be

built that will not settle in clay and mud.

Hydrology and environmental issues

Geology and geologic principles can be applied to various environmental problems such as stream restoration, the restoration of brownfields, and the understanding of the interaction between natural habitat and the geologic environment. Groundwater hydrology, or hydrogeology, is used to locate groundwater, which can often provide a ready supply of uncontaminated water and is especially important in arid regions, and to monitor the spread of contaminants in groundwater wells.

Geologists also obtain data through stratigraphy, boreholes, core samples, and ice cores. Ice cores and sediment cores are used to for paleoclimate reconstructions, which tell geologists about past and present temperature, precipitation, and sea level across the globe. These datasets are our primary source of information on global climate change outside of instrumental data.

Natural hazards

Geologists and geophysicists study natural hazards in order to enact safe building codes and warning systems that are used to prevent loss of property and life.

Examples of important natural hazards that are pertinent to geology (as

opposed those that are mainly or only pertinent to meteorology) are:

Rockfall in the Grand Canyon

History of geology

William Smith's geologic map of England, Wales, and southern Scotland. Completed in 1815, it was the second national-scale geologic map, and by far the most accurate of its time.

The study of the physical material of the Earth dates back at least to ancient Greece when Theophrastus (372–287 BCE) wrote the work Peri Lithon (On Stones). During the Roman period, Pliny the Elder wrote in detail of the many minerals and metals then in practical use – even correctly noting the origin of amber.

Some modern scholars, such as Fielding H. Garrison, are of the opinion that the origin of the science of geology can be traced to Persia after the Muslim conquests had come to an end. Abu al-Rayhan al-Biruni (973–1048 CE) was one of the earliest Persian geologists, whose works included the earliest writings on the geology of India, hypothesizing that the Indian subcontinent was once a sea. Drawing from Greek and Indian scientific literature that were not destroyed by the Muslim conquests, the Persian scholar Ibn Sina

(Avicenna, 981–1037) proposed detailed explanations for the formation

of mountains, the origin of earthquakes, and other topics central to

modern geology, which provided an essential foundation for the later

development of the science. In China, the polymath Shen Kuo

(1031–1095) formulated a hypothesis for the process of land formation:

based on his observation of fossil animal shells in a geological stratum in a mountain hundreds of miles from the ocean, he inferred that the land was formed by erosion of the mountains and by deposition of silt.

Nicolas Steno (1638–1686) is credited with the law of superposition, the principle of original horizontality, and the principle of lateral continuity: three defining principles of stratigraphy.

The word geology was first used by Ulisse Aldrovandi in 1603, then by Jean-André Deluc in 1778 and introduced as a fixed term by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure in 1779. The word is derived from the Greek γῆ, gê, meaning "earth" and λόγος, logos, meaning "speech".

But according to another source, the word "geology" comes from a

Norwegian, Mikkel Pedersøn Escholt (1600–1699), who was a priest and

scholar. Escholt first used the definition in his book titled, Geologia Norvegica (1657).

William Smith (1769–1839) drew some of the first geological maps and began the process of ordering rock strata (layers) by examining the fossils contained in them.

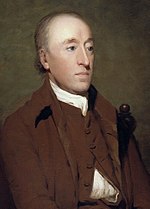

James Hutton is often viewed as the first modern geologist. In 1785 he presented a paper entitled Theory of the Earth to the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

In his paper, he explained his theory that the Earth must be much older

than had previously been supposed to allow enough time for mountains to

be eroded and for sediments

to form new rocks at the bottom of the sea, which in turn were raised

up to become dry land. Hutton published a two-volume version of his

ideas in 1795 (Vol. 1, Vol. 2).

Scotsman James Hutton, father of modern geology

Followers of Hutton were known as Plutonists because they believed that some rocks were formed by vulcanism, which is the deposition of lava from volcanoes, as opposed to the Neptunists, led by Abraham Werner, who believed that all rocks had settled out of a large ocean whose level gradually dropped over time.

The first geological map of the U.S. was produced in 1809 by William Maclure.

In 1807, Maclure commenced the self-imposed task of making a geological

survey of the United States. Almost every state in the Union was

traversed and mapped by him, the Allegheny Mountains being crossed and recrossed some 50 times. The results of his unaided labours were submitted to the American Philosophical Society in a memoir entitled Observations on the Geology of the United States explanatory of a Geological Map, and published in the Society's Transactions, together with the nation's first geological map. This antedates William Smith's geological map of England by six years, although it was constructed using a different classification of rocks.

Sir Charles Lyell first published his famous book, Principles of Geology, in 1830. This book, which influenced the thought of Charles Darwin, successfully promoted the doctrine of uniformitarianism. This theory states that slow geological processes have occurred throughout the Earth's history and are still occurring today. In contrast, catastrophism

is the theory that Earth's features formed in single, catastrophic

events and remained unchanged thereafter. Though Hutton believed in

uniformitarianism, the idea was not widely accepted at the time.

Much of 19th-century geology revolved around the question of the Earth's exact age. Estimates varied from a few hundred thousand to billions of years. By the early 20th century, radiometric dating

allowed the Earth's age to be estimated at two billion years. The

awareness of this vast amount of time opened the door to new theories

about the processes that shaped the planet.

Some of the most significant advances in 20th-century geology have been the development of the theory of plate tectonics

in the 1960s and the refinement of estimates of the planet's age. Plate

tectonics theory arose from two separate geological observations: seafloor spreading and continental drift. The theory revolutionized the Earth sciences. Today the Earth is known to be approximately 4.5 billion years old.