Racial inequality in the United States refers to social advantages and disparities that affect different races within the United States.

These inequities may be manifested in the distribution of wealth,

power, and life opportunities afforded to people based on their race or

ethnicity, both historic and modern. These can also be seen as a result

of historic oppression, inequality of inheritance, or overall prejudice, especially against minority groups.

Definitions

In

social science, racial inequality is typically analyzed as "imbalances

in the distribution of power, economic resources, and opportunities."

Racial inequalities have manifested in American society in ways ranging

from racial disparities in wealth, poverty rates, housing patterns,

educational opportunities, unemployment rates, and incarceration rates.

Some claim that current racial inequalities in the U.S. have their

roots in over 300 years of cultural, economic, physical, legal, and

political discrimination based on race.

Manifestations of racial inequality

There are vast differences in wealth across racial groups in the United States. The wealth gap

between white and African-American families nearly tripled from $85,000

in 1984 to $236,500 in 2009. There are many causes, including years of

home ownership, household income, unemployment, and education, but

inheritance might be the most important.

Health disparities

Racial wealth gap

A study by the Brandeis University

Institute on Assets and Social Policy which followed the same sets of

families for 25 years found that there are vast differences in wealth

across racial groups in the United States. The wealth gap between

Caucasian and African-American families studied nearly tripled, from

$85,000 in 1984 to $236,500 in 2009. The study concluded that factors

contributing to the inequality included years of home ownership (27%),

household income (20%), education (5%), and familial financial support

and/or inheritance (5%).

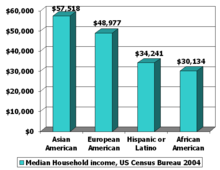

Median household income along ethnic lines in the United States.

Wealth

can be defined as "the total value of things families own minus their

debts." In contrast, income can be defined as, "earnings from work,

interest and dividends, pensions, and transfer payments."

Wealth is an important factor in determining the quality of both

individual and family life chances because it can be used as a tool to

secure a desired quality of life or class status and enables individuals

who possess it to pass their class status to their children. Family

inheritance, which is passed down from generation to generation, helps

with wealth accumulation. Wealth can also serve as a safety net against fluctuations in income and poverty.

There is a large gap between the wealth of minority households

and White households within the United States. The Pew Research Center's

analysis of 2009 government data says the median wealth of white

households is 20 times that of black households and 18 times that of

Hispanic households.

In 2009 the typical black household had $5,677 in wealth, the typical

Hispanic had $6,325, and the typical White household had $113,149.

Furthermore, 35% of African American and 31% of Hispanic households had

zero or negative net worth in 2009 compared to 15% of White households.

While in 2005 median Asian household wealth was greater than White

households at $168,103, by 2009 that changed when their net worth fell

54% to $78,066, partially due to the arrival of new Asian immigrants

since 2004; not including newly arrived immigrants, Asian net wealth

only dropped 31%. As shown on "Eurweb - Electronic Urban Report"

According to the Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, of the 14

million black households, only 5% have more than $350,000 in net worth

while nearly 30% of white families have more than this amount. Less than

1% of black families have over a million in net assets. while nearly

10% of white households, totaling over 8 million families have more than

1.3 million in net worth.

Lusardi states that African Americans and Hispanics are more

likely to face means-tested programs that discourage asset possession

due to higher poverty rates.

One-fourth of African Americans and Hispanics approach retirement with

less than $1,000 net worth (without considering pensions and Social

Security). Lower financial literacy is correlated with poor savings and

adjustment behavior. Education is a strong predictor for wealth.

One-fourth of African Americans and Hispanics that have less than a

high school education have no wealth, but even with increased education,

large differences in wealth remain.

Conley believes that the cause of Black-White wealth inequality

may be related to economic circumstances and poverty because the

economic disadvantages of African Americans can be effective in harming

efforts to accumulate wealth.

However, there is a five times greater chance of downward mobility from

the top quartile to the bottom quartile for African Americans than

there is for White Americans; correspondingly, African Americans rise to

the top quartile from the bottom quartile at half the rate of White

Americans. Bowles and Gintis conclude from this information that

successful African Americans do not transfer the factors for their

success as effectively as White Americans do.

Other factors to consider in the recent widening of the minority wealth gap are the mortgage crisis and credit crunch that began in 2007-2008. The Pew Research Center found that plummeting house values

were the main cause of the wealth change from 2005 to 2009. Hispanics

were hit the hardest by the housing market meltdown possibly because a

disproportionate share of Hispanics live in California, Florida, Nevada,

and Arizona, which are among the states with the steepest declines in

housing values.

From 2005 to 2009 Hispanic homeowners' home equity declined by Half,

from $99,983 to $49,145, with homeownership rate decreasing by 4% to

47%. A 2015 Measure of America study commissioned by the ACLU on the long-term consequences of discriminatory lending practices found that the financial crisis will likely widen the black-white wealth gap for the next generation.

History

Africans were first brought to the United States as slaves. While free African-Americans owned around $50 million by 1860, farm tenancy and sharecropping replaced slavery after the American Civil War

because newly freed African American farmers did not own land or

supplies and had to depend on the White Americans who rented the land

and supplies out to them. At the same time, southern Blacks were trapped

in debt and denied banking services while White citizens were given low

interest loans to set up farms in the Midwest and Western United

States. White homesteaders were able to go West and obtain unclaimed

land through government grants, while the land grants and rights of

African Americans were rarely enforced.

After the Civil War the Freedman's Bank

helped to foster wealth accumulation for African Americans. However, it

failed in 1874, partially because of suspicious high-risk loans to

White banks and the Panic of 1873.

This lowered the support African Americans had to open businesses and

acquire wealth. In addition, after the bank failed, taking the assets of

many African Americans with it, many African Americans did not trust

banks. There was also the threat of lynching to any African American who

achieved success.

In addition, when Social Security was first created during the Great Depression,

it exempted agricultural and domestic workers, which disproportionately

affected African Americans and Hispanics. Consequently, the savings of

retired or disabled African Americans was spent during old age instead

of handed down and households had to support poor elderly family

members. The Homeowner's Loan Corporation that helped homeowners during

the Great Depression gave African American neighborhoods the lowest

rating, ensuring that they defaulted at greater rates than White

Americans. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) and Veteran's Administration (VA) shut out African Americans by giving loans to suburbs instead of central cities after they were first founded.

Inheritance and parental financial assistance

Bowman

states that "in the United States, the most significant aspect of

multigenerational wealth distribution comes in the forms of gifts and

inheritances." However, the multigenerational absence of wealth and

asset attainment for African Americans makes it almost impossible for

them to make significant contributions of wealth to the next generation.

Data shows that financial inheritances could account for 10 to 20

percent of the difference between African American and White American

household wealth.

Using the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) of 1992 Avery and

Rendall estimated that only around one-tenth of African Americans

reported receiving inheritances or substantial inter vivo transfers

($5,000 or more) compared to one-third of White Americans. In addition,

the 1989 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) reported that the mean and

median values of those money transfers were significantly higher for

White American households: the mean was $148,578 households compared to

$85,598 for African American households and the median was $58,839 to

$42,478. The large differences in wealth in the parent-generations were a

dominant factor in prediction the differences between African American

and White American prospective inheritances.

Avery and Rendall used 1989 SCF data to discover that the mean value in

2002 of White Americans' inheritances was 5.46 times that of African

Americans', compared to 3.65 that of current wealth. White Americans

received a mean of $28,177 that accounted for 20.7% of their mean wealth

while African Americans received a mean of $5,165 that accounted for

13.9% of their mean current wealth. Non-inherited wealth was more

equally distributed than inherited wealth.

Avery and Rendall found that family attributes favored White

Americans when it came to factor influencing the amount of inheritances.

African Americans were 7.3% less likely to have live parents, 24.5%

more likely to have three or more siblings, and 30.6% less likely to be

married or cohabiting (meaning there are two people who could gain

inheritances to contribute to the household)

Keister discovered that large family size has a negative effect on

wealth accumulation. These negative effects are worse for the poor and

African Americans and Hispanics are more likely to be poor and have

large families. More children also decrease the amount of gifts parents

can give and the inheritance they leave behind for the children.

Angel's research into inheritance showed that older Mexican

American parents may give less financial assistance to their children

than non-Hispanic White Americans because of their relatively high

fertility rate so children have to compete for the available money.

There are studies that indicate that elderly Hispanic parents of all

backgrounds live with their adult children due to poverty and would

choose to do otherwise, even if they had the resources to do so. African

American and Latino families are less likely to financially aid adult

children than non-Hispanic White families.

Income effects

The racial wealth gap is visible in terms of dollar for dollar wage

and wealth comparisons. For example, middle-class Blacks earn seventy

cents for every dollar earned by similar middle-class Whites. Race can be seen as the "strongest predictor" of one's wealth.

Even at similar education levels, minorities typically earn less

than whites. Education may boost earnings less for minorities than for

whites, although all groups typically see benefits from additional

education.

Krivo and Kaufman found that information supporting the fact that

increases in income does not affect wealth as much for minorities as it

does for White Americans. For example, a $10,000 increase in income for

White Americans increases their home equity $17,770 while the same

increase only increase the home equities for Asians by $9,500, Hispanics

by $15,150, and African Americans by $15,900.

Financial decisions

Investments

Conley

states that differences between African American and White American

wealth begin because people with higher asset levels can take advantage

of riskier investment instruments with higher rates of returns. Unstable

income flows may lead to "cashing in" of assets or accumulation of debt

over time, even if the time-averaged streams of income and savings are

the same. African Americans may be less likely to invest in the stock

market because they have a smaller parental head-start and safety net.

Chong, Phillips and Phillips state that African Americans,

Hispanics, and Asians invest less heavily in stocks than White

Americans.

Hispanics and in some ways African Americans accumulate wealth slower

than White Americans because of preference for near-term saving,

favoring liquidity and low investment risk at the expense of higher

yielding assets. These preferences may be due to low financial literacy

leading to a lack of demand for investment services.

According to Lusardi, even though the stock market increased in value

in the 1990s, only 6-7% of African Americans and Hispanics held stocks,

so they did not benefit as much from the value increase.

Use of financial services

The

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in 2009 found that 7.7% of United

States households are "unbanked". Minorities are more likely than White

Americans to not have a banking account. 3.5% of Asians, 3.3% of White

Americans, 21.7% of African Americans and 19.3% of Hispanics and 15.6%

of remaining racial/ethnic categories do not have banking accounts.

Lusardi's research revealed that education increases one's

chances of having a banking account. A full high school education

increases the chance of having a checking account by 15% compared to

only an elementary education; having a parent with a high school

education rather than only an elementary education increases one's

chances of having a checking account by 2.8%. This difference in

education level may explain the large proportion of "unbanked"

Hispanics. The 2002 National Longitudinal Survey found that while only

3% of White Americans and 4% of African Americans had only an elementary

education, close to 20% of Hispanics did and 43% of Hispanics had less

than a high school education

Ibarra and Rodriguez believe that another factor that influences the

Hispanic use of banking accounts is credit. Latinos are also more likely

than White Americans or African Americans to have no or a thin credit

history: 22% of Latinos have no credit score in comparison to 4% of

White Americans and 3% of African Americans.

Not taking other variables into account, Chong, Phillips, and

Phillips survey of zip codes found that minority neighborhoods don't

have the same access to financial planning services as White

neighborhoods. There is also client segregation by investable assets.

More than 80% of financial advisors prefer that clients have at least

$100,000 in investable assets and more than 50% have a minimum asset

requirement of $500,000 or above. Because of this, financial planning is

possibly beyond the reach of those with low income, which comprises a

large portion of African-Americans and Hispanics.

Fear of discrimination is another possible factor. Minorities may be

distrustful of banks and lack of trust was commonly reported as why

minorities, people with low education, and the poor chose not to have

banking accounts.

Poverty

There are large differences in poverty rates

across racial groups. In 2009, the poverty rate was 9.9% for

non-Hispanic Whites, 12.1% for Asians, 26.6% for Hispanics, and 27.4%

for Blacks.

This data illustrates that Hispanics and Blacks experience

disproportionately high percentages of poverty in comparison to

non-Hispanics Whites and Asians. In discussing poverty, it is important

to distinguish between episodic poverty and chronic poverty.

Episodic poverty

The U.S. Census Bureau defines episodic poverty as living in poverty for less than 36 consecutive months.

From the period between 2004 and 2006 the episodic poverty rate was

22.6% for non-Hispanic Whites, 44.5% for Blacks, and 45.8% for

Hispanics. Blacks and Hispanics experience rates of episodic poverty that are nearly double the rates of non-Hispanic Whites.

Chronic poverty

The U.S. Census Bureau defines chronic poverty as living in poverty for 36 or more consecutive months.

From the period between 2004 and 2006 the chronic poverty rate was 1.4%

for non-Hispanic Whites, 4.5% for Hispanics, and 8.4% for Blacks. Hispanics and Blacks experience much higher rates of chronic poverty when compared to non-Hispanic Whites.

Length of poverty spell

The

U.S. Census Bureau defines length of poverty spell as the number of

months spent in poverty. The median length of poverty spells was 4

months for non-Hispanic Whites, 5.9 months for Blacks, and 6.2 months

for Hispanics.

The length of time spent in poverty varies by race. Non-Hispanic Whites

experience the shortest length of poverty spells when compared to

Blacks and Hispanics.

Housing

About 25% of African-Americans own a house in America.

Home ownership

Home ownership is a crucial means by which families can accumulate wealth. Over a period of time, homeowners accumulate home equity

in their homes. In turn, this equity can contribute substantially to

the wealth of homeowners. In summary, home ownership allows for the

accumulation of home equity, a source of wealth, and provides families

with insurance against poverty.

Ibarra and Rodriguez state that home equity is 61% of the net worth of

Hispanic homeowners, 38.5% of the net worth of White homeowners, and 63%

of the net worth of African-American homeowners.

Conley remarks that differences in rates of home ownership and housing

value accrual may lead to lower net worth in the parental generation,

which disadvantages the next.

There are large disparities in homeownership rates by race. In 2017, the home ownership rate was 72.5% for non-Hispanic Whites, 46.1% for Hispanics, and 42.0% for Blacks.

From this data, non-Hispanic Whites own homes at a much higher rate

that all other races, while Hispanics and Blacks own homes at much lower

rates. This means that a high percentage of Hispanic and Black

populations do not receive the benefits, such as wealth accumulation and

insurance against poverty, that owning a home provides.

Home equity

There

is a discrepancy in relation to race in terms of housing value. On

average, the economic value of Black-owned units is 35% less than

similar White-owned units. Thus, on average, Black-owned units sell for

35% less than similar White-owned units.

Krivo and Kaufman state that while median home value of White Americans

is at least $20,000 more than that of African Americans and Hispanics,

these differences are not a result of group differences in length of

residences because Asians have the most equity on their homes but have

lived in them for the shortest average period. African American and

Hispanic mortgage holders are 1.5 to 2.5 times more likely to pay 9% or

more on interest. Krivo and Kaufman calculate that the

African-American/White gap in mortgage interest rates is 0.39%, which

translates to a difference of $5,749 on the median home loan payment of a

30-year mortgage of a $53,882 home. The Hispanic/White gap (0.17%)

translates to Hispanics paying $3,441 more on a 30-year mortgage on the

median valued Hispanic home loan of $80,000. The authors conclude that

the extra money could have been reinvested into wealth accumulation.

Krivo and Kaufman also postulate that the types of mortgage loans

minorities obtain contributes to the differences in home equity. FHA

and VA loans make up one-third or more of primary loans for African

Americans and Hispanics, while only 18% for White Americans and 16% for

Asians. These loans require lower down payments and cost more than

conventional mortgages, which contributes to a slower accumulation of

equity. Asians and Hispanics have lower net equity on houses partly

because they are youngest on average, but age has only a small effect on

the Black-White gap in home equity. Previously owning a home can allow

the homeowner to use money from selling the previous home to invest and

increase the equity of later housing. Only 30% of African Americans in

comparison to 60% of White Americas had previously owned a home.

African-Americans, Asians, and Hispanics gain lower home equity returns

in comparison to White Americans with increases in income and education.

Residential segregation

Residential segregation can be defined as, "physical separation of the residential locations between two groups.

There are large discrepancies between races involving geographic

location of residence. In the United States, poverty and affluence have

become very geographically concentrated. Much residential segregation

has been a result of the discriminatory lending practice of Redlining, which delineated certain, primarily minority race neighborhoods, as risky for investment or lending.

The result has been neighborhoods with concentrated investment, and

others neighborhoods where banks are less inclined to invest. Most

notably, this geographic concentration of affluence and poverty can be

seen in the comparison between suburban and urban populations. The

suburbs have traditionally been primarily White populations, while the

majority of urban inner city populations have traditionally been composed of racial minorities.

Results from the last few censuses suggest that more and more

inner-ring suburbs around cities also are becoming home to racial

minorities as their populations grow. As of 2017, most residents of the

United States live in "radicalized and economically segregated

neighborhoods".

Education

In the United States, funding for public education relies greatly on

local property taxes. Local property tax revenues may vary between

different neighborhoods and school districts. This variance of property

tax revenues amongst neighborhoods and school districts leads to

inequality in education. This inequality manifests in the form of

available school financial resources which provide educational

opportunities, facilities, and programs to students.

Returning to the concept of residential segregation, it is known

that affluence and poverty have become both highly segregated and

concentrated in relation to race and location.

Residential segregation and poverty concentration is most markedly seen

in the comparison between urban and suburban populations in which

suburbs consist of majority White populations and inner-cities consist

of majority minority populations.

According to Barnhouse-Walters (2001), the concentration of poor

minority populations in inner-cities and the concentration of affluent

White populations in the suburbs, "is the main mechanism by which racial

inequality in educational resources is reproduced."

Unemployment rates

In

2016, the unemployment rate was 3.8% for Asians, 4.6% for non-Hispanic

Whites, 6.1% for Hispanics, and 9.0% for Blacks, all over the age of 16.

In terms of unemployment, it can be seen that there are two-tiers:

relatively low unemployment for Asians and Whites, relatively high

unemployment for Hispanics and Blacks.

Potential explanations

Several theories have been offered to explain the large racial gap in unemployment rates:

- Segregation and job decentralization

This theory argues that the effects of racial segregation pushed

Blacks and Hispanics into the central city during a time period in which

jobs and opportunities moved to the suburbs. This led to geographic

separation between minorities and job opportunities which was compounded

by struggles to commute to jobs in the suburbs due to lack of means of

transportation. This ultimately led to high unemployment rates among

minorities.

- White gains

This theory argues that the reason minority disadvantage exists is

because the majority group is able to benefit from it. For example, in

terms of the labor force, each job not taken by a Black person could be

job that gets occupied by a White person. This theory is based on the

view that the White population has the most to gain from the

discrimination of minority groups. In areas where there are large

minority groups, this view predicts high levels of discrimination to

occur for the reason that White populations stand to gain the most in

those situations.

- Job skill differentials

This theory argues that the unemployment disparity can be attributed

to lower rates of academic success among minority groups (especially

black Americans) leading to a lack of skills necessary for entering the

modern work force.

Crime rates and incarceration

In 2008, the prison population under federal and state correctional

jurisdiction was over 1,610,446 prisoners. Of these prisoners, 20% were

Hispanic (compared to 16.3% of the U.S. population that is Hispanic),

34% were White (compared to 63.7% of the U.S. population that is White),

and 38% were Black (compared to 12.6% of the U.S. population that is

Black). Additionally, Black males were imprisoned at a rate 6.5 times higher than that of their White male counterparts.

According to a 2012 study by the U.S. Census Bureau, "over half the

inmates incarcerated in our nation's jails is either black or Hispanic."

According to a report by the National Council of La Raza, research

obstacles undermine the census of Latinos in prison, and "Latinos in the

criminal justice system are seriously undercounted. The true extent of

the overrepresentation of Latinos in the system probably is

significantly greater than researchers have been able to document.

Consequences of a criminal record

After being released from prison, the consequences of having a criminal record

are immense. Over 40 percent who are released will return to prison

within the next few years. Those with criminal records who do not return

to prison face significant struggles to find quality employment and

income outcomes compared to those who do not have criminal records.

Potential causes

- Poverty

A potential cause of such disproportionately high incarceration rates

for Black Americans is that Black Americans are disproportionately

poor.

Conviction is a crucial part of the process that leads to either guilt

or innocence. There are two important factors that play a role in this

part of the process: the ability to make bail and the ability to access

high-quality legal counsel. Due to the fact that both of these important

factors cost money, it is unlikely that poor Black Americans are able

to afford them and benefit from them.

Sentencing is another crucial part of the process that determines how

long individuals will remain incarcerated. Several sociological studies

have found that poor offenders receive longer sentences for violent

crimes and crimes involving drug use, unemployed offenders are more

likely to be incarcerated than their employed counterparts, and then

even with similar crimes and criminal records minorities were imprisoned

more often than Whites.

- Racial profiling

Racial profiling is defined as,"any police-initiated action that

relies on the race, ethnicity, or national origin, rather than the

behavior of an individual or information that leads the police to a

particular individual who has been identified as being, or having been,

engaged in criminal activity." Another potential cause for the disproportionately high incarceration rates of Blacks and Hispanics

is that racial profiling occurs at higher rates for Blacks and

Hispanics. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva states that racial profiling can

perhaps explain the over representation of Blacks and Hispanics in U.S.

prisons. According to Michael L. Birzer, professor of criminal justice at Wichita State University

and director of its School of Community Affairs, "racial minorities,

particularly African Americans, have had a long and troubled history of

disparate treatment by United States Criminal Justice Authorities."

- Racial segregation

"Racial residential segregation is a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health".

Racial segregation can result in decreased opportunities for minority

groups in income, education, etc. While there are laws against racial

segregation, study conducted by D. R. Williams and C. Collins focuses

primarily on the impacts of racial segregation, which leads to

differences between races.

Police brutality

Significant racial discrepancies have been reported in the United

States involving police brutality. Police brutality in the United States

is defined as "the unwarranted or excessive and often illegal use of

force against civilians by U.S. police officers."

It can come in the form of murder, assault, mayhem, or torture, as well

as less physical means of violence including general harassment, verbal

abuse, and intimidation.

The origins of racial inequality by way of police brutality in America

date all the way back to colonial times. During this time when Africans

were enslaved by whites, enslavement became so widespread that slaves

began to outnumber whites in some colonies. Due to fear of rebellions,

insurrections, and slave riots, whites began to organize groups of

vigilantes who would use force to keep slaves from rebelling against

their owners. Men ages six to sixty were required to patrol slave

residences, searching for any slaves that needed to be kept under

control. When

the first American police department was established in 1838, African

Americans soon became the target of police brutality as they fled the

south. In 1929, the Illinois crime survey reported that although

African-Americans only made up five percent of Illinois's population,

they consisted of 30 percent of victims of police killings.

During the civil rights era, the existence of the racial

disparities surrounding police brutality only became more evident. As

protests against police brutality became more prevalent, police would

use tactics such as police dogs or fire hoses to control the protesters,

even if they were peacefully protesting. In 1991, video footage was

released of cab driver Rodney King

being hit over 50 times by multiple police with their batons. The

police were later acquitted for their actions. Allegations of police

brutality continue to plague American police. An alleged example includes Philando Castile,

a 32 year old black male who was pulled over for a broken taillight.

After being told by the police man, officer Yanez, to take out his

license and insurance, Castile let the officer know he had a firearm and

that he was reaching into his pocket to get his wallet. In a matter of

seconds the officer pulled out his gun and shot Castile 5 times, killing

him in front of his girlfriend and 4-year-old daughter. He claimed he

feared for his life because he believed Castile was pulling his own gun

from his pocket.

He was acquitted at trial, with one juror explaining that the decision

hinged on the specific wording of the law under which he was charged.

A study done by Joshua Correll at the University of Chicago shows what is called “The police officers dilemma,”

by setting up a video game in which police are given scenarios

involving both black and white men holding either a gun or

non-threatening objects such as cellphones. Their task is to only shoot

the men that are carrying guns. It was found in this experiment that

armed black men were shot more frequently than armed white men and were

also shot more quickly. The police would also often mistakenly shoot the

unarmed black targets, while neglecting to shoot the armed white

targets.

Cody T. Ross, a doctoral student studying anthropology concluded that

there is "evidence of a significant bias in the killing of unarmed black

Americans relative to unarmed white Americans, in that the probability

of being {black, unarmed, and shot by police} is about 3.49 times the

probability of being {white, unarmed, and shot by police} on average."

Color blind racism

It is hypothesized by some scholars, such as Michelle Alexander, that in the post-Civil Rights era, the United States has now switched to a new form of racism known as color blind racism. Color-blind racism refers to "contemporary racial inequality as the outcome of nonracial dynamics."

The types of practices that take place under color blind racism are "subtle, institutional, and apparently nonracial." These practices are not racially overt in nature such as racism under slavery, segregation, and Jim Crow laws.

Instead, color blind racism flourishes on the idea that race is no

longer an issue in this country and that there are non-racial

explanations for the state of inequality in the U.S. Eduardo

Bonilla-Silva writes that there are 4 frames of color-blind racism that

support this view:

- Abstract liberalism – Abstract liberalism uses ideas associated with political liberalism. This frame is based in liberal ideas such as equal opportunity, individualism, and choice. It uses these ideas as a basis to explain inequality.

- Naturalization – Naturalization explains racial inequality as a cause of natural occurrences. It claims that segregation is not the result of racial dynamics. Instead it is the result of the naturally occurring phenomena of individuals choosing likeness as their preference.

- Cultural racism – Cultural racism explains racial inequality through culture. Under this frame, racial inequalities are described as the result of stereotypical behavior of minorities. Stereotypical behavior includes qualities such as laziness and teenage pregnancy.

- Minimization of racism – Minimization of racism attempts to minimize the factor of race as a major influence in affecting the life chances of minorities. It writes off instances and situations that could be perceived as discrimination to be hypersensitivity to the topic of race.

Natural disasters

When

a disaster strikes--be it a hurricane, tornado, or fire--some people

are inherently more prepared than others. "While all members of

populations are affected by disasters, research findings show that

racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to evacuate and more

affected by disasters" than their Caucasian counterparts.

"During Hurricane Katrina, the large number of people seeking safety in

designated shelters were disproportionately black. In addition, the

mortality rate for blacks was 1.7 to 4 times higher than that of whites

for all people ≥ 18."

After Hurricane Katrina, many African Americans felt abandoned by the

United States Government. 66% of African Americans "said that 'the

government's response to [Katrina] would have been faster if most of the

victims had been white.'"

For a disproportionate share of the impoverished in New Orleans, many

had, and continue to have, a difficult time preparing for storms.

Factors such as "cultural ignorance, ethnic insensitivity, racial

isolation and racial bias in housing, information dissemination, and

relief assistance" all greatly contribute to the disparities in disaster

preparedness.