Thermal oxidizers purify industrial air flows.

Pollution is the introduction of contaminants into the natural environment that cause adverse change. Pollution can take the form of chemical substances or energy, such as noise, heat or light. Pollutants,

the components of pollution, can be either foreign substances/energies

or naturally occurring contaminants. Pollution is often classed as point source or nonpoint source pollution.

In 2015, pollution killed 9 million people in the world.

Major forms of pollution include: Air pollution, light pollution, littering, noise pollution, plastic pollution, soil contamination, radioactive contamination, thermal pollution, visual pollution, water pollution.

History

Air pollution has always accompanied civilizations. Pollution started from prehistoric times, when man created the first fires. According to a 1983 article in the journal Science, "soot"

found on ceilings of prehistoric caves provides ample evidence of the

high levels of pollution that was associated with inadequate ventilation

of open fires." Metal forging appears to be a key turning point in the creation of significant air pollution levels outside the home. Core samples of glaciers in Greenland indicate increases in pollution associated with Greek, Roman, and Chinese metal production.

Urban pollution

Air pollution in the US, 1973

The burning of coal and wood, and the presence of many horses in

concentrated areas made the cities the primary sources of pollution. The

Industrial Revolution brought an infusion of untreated chemicals and wastes into local streams that served as the water supply. King Edward I of England banned the burning of sea-coal by proclamation in London in 1272, after its smoke became a problem;

the fuel was so common in England that this earliest of names for it

was acquired because it could be carted away from some shores by the wheelbarrow.

It was the industrial revolution that gave birth to environmental

pollution as we know it today. London also recorded one of the earlier

extreme cases of water quality problems with the Great Stink on the Thames of 1858, which led to construction of the London sewerage system soon afterward. Pollution issues escalated as population growth far exceeded viability of neighborhoods to handle their waste problem. Reformers began to demand sewer systems and clean water.

In 1870, the sanitary conditions in Berlin were among the worst in Europe. August Bebel recalled conditions before a modern sewer system was built in the late 1870s:

Waste-water from the houses collected in the gutters running alongside the curbs and emitted a truly fearsome smell. There were no public toilets in the streets or squares. Visitors, especially women, often became desperate when nature called. In the public buildings the sanitary facilities were unbelievably primitive....As a metropolis, Berlin did not emerge from a state of barbarism into civilization until after 1870.

The primitive conditions were intolerable for a world national capital, and the Imperial German

government brought in its scientists, engineers, and urban planners to

not only solve the deficiencies, but to forge Berlin as the world's

model city. A British expert in 1906 concluded that Berlin represented

"the most complete application of science, order and method of public

life," adding "it is a marvel of civic administration, the most modern

and most perfectly organized city that there is."

The emergence of great factories and consumption of immense quantities of coal gave rise to unprecedented air pollution and the large volume of industrial chemical discharges added to the growing load of untreated human waste. Chicago and Cincinnati

were the first two American cities to enact laws ensuring cleaner air

in 1881. Pollution became a major issue in the United States in the

early twentieth century, as progressive reformers

took issue with air pollution caused by coal burning, water pollution

caused by bad sanitation, and street pollution caused by the 3 million

horses who worked in American cities in 1900, generating large

quantities of urine and manure.

As historian Martin Melosi notes, The generation that first saw

automobiles replacing the horses saw cars as "miracles of cleanliness.". By the 1940s, however, automobile-caused smog was a major issue in Los Angeles.

Other cities followed around the country until early in the 20th

century, when the short lived Office of Air Pollution was created under

the Department of the Interior. Extreme smog events were experienced by the cities of Los Angeles and Donora, Pennsylvania in the late 1940s, serving as another public reminder.

Air pollution would continue to be a problem in England,

especially later during the industrial revolution, and extending into

the recent past with the Great Smog of 1952.

Awareness of atmospheric pollution spread widely after World War II,

with fears triggered by reports of radioactive fallout from atomic

warfare and testing. Then a non-nuclear event – the Great Smog of 1952 in London – killed at least 4000 people. This prompted some of the first major modern environmental legislation: the Clean Air Act of 1956.

Pollution began to draw major public attention in the United States

between the mid-1950s and early 1970s, when Congress passed the Noise Control Act, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act.

Smog Pollution in Taiwan

Severe incidents of pollution helped increase consciousness. PCB dumping in the Hudson River resulted in a ban by the EPA on consumption of its fish in 1974. National news stories in the late 1970s – especially the long-term dioxin contamination at Love Canal starting in 1947 and uncontrolled dumping in Valley of the Drums – led to the Superfund legislation of 1980. The pollution of industrial land gave rise to the name brownfield, a term now common in city planning.

The development of nuclear science introduced radioactive contamination, which can remain lethally radioactive for hundreds of thousands of years. Lake Karachay – named by the Worldwatch Institute as the "most polluted spot" on earth – served as a disposal site for the Soviet Union throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Chelyabinsk, Russia, is considered the "Most polluted place on the planet".

Nuclear weapons continued to be tested in the Cold War,

especially in the earlier stages of their development. The toll on the

worst-affected populations and the growth since then in understanding

about the critical threat to human health posed by radioactivity has also been a prohibitive complication associated with nuclear power. Though extreme care is practiced in that industry, the potential for disaster suggested by incidents such as those at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl pose a lingering specter of public mistrust. Worldwide publicity has been intense on those disasters. Widespread support for test ban treaties has ended almost all nuclear testing in the atmosphere.

International catastrophes such as the wreck of the Amoco Cadiz oil tanker off the coast of Brittany in 1978 and the Bhopal disaster

in 1984 have demonstrated the universality of such events and the scale

on which efforts to address them needed to engage. The borderless

nature of atmosphere and oceans inevitably resulted in the implication

of pollution on a planetary level with the issue of global warming. Most recently the term persistent organic pollutant (POP) has come to describe a group of chemicals such as PBDEs and PFCs

among others. Though their effects remain somewhat less well understood

owing to a lack of experimental data, they have been detected in

various ecological habitats far removed from industrial activity such as

the Arctic, demonstrating diffusion and bioaccumulation after only a relatively brief period of widespread use.

Plastic Pollution in Ghana, 2018

A much more recently discovered problem is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a huge concentration of plastics, chemical sludge and other debris which has been collected into a large area of the Pacific Ocean by the North Pacific Gyre.

This is a less well known pollution problem than the others described

above, but nonetheless has multiple and serious consequences such as

increasing wildlife mortality, the spread of invasive species and human

ingestion of toxic chemicals. Organizations such as 5 Gyres have researched the pollution and, along with artists like Marina DeBris, are working toward publicizing the issue.

Pollution introduced by light at night is becoming a global

problem, more severe in urban centers, but nonetheless contaminating

also large territories, far away from towns.

Growing evidence of local and global pollution and an increasingly informed public over time have given rise to environmentalism and the environmental movement, which generally seek to limit human impact on the environment.

Forms of pollution

The Lachine Canal in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Blue

drain and yellow fish symbol used by the UK Environment Agency to raise

awareness of the ecological impacts of contaminating surface drainage.

The major forms of pollution are listed below along with the particular contaminant relevant to each of them:

- Air pollution: the release of chemicals and particulates into the atmosphere. Common gaseous pollutants include carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and nitrogen oxides produced by industry and motor vehicles. Photochemical ozone and smog are created as nitrogen oxides and hydrocarbons react to sunlight. Particulate matter, or fine dust is characterized by their micrometre size PM10 to PM2.5.

- Light pollution: includes light trespass, over-illumination and astronomical interference.

- Littering: the criminal throwing of inappropriate man-made objects, unremoved, onto public and private properties.

- Noise pollution: which encompasses roadway noise, aircraft noise, industrial noise as well as high-intensity sonar.

- Plastic pollution: involves the accumulation of plastic products and microplastics in the environment that adversely affects wildlife, wildlife habitat, or humans.

- Soil contamination occurs when chemicals are released by spill or underground leakage. Among the most significant soil contaminants are hydrocarbons, heavy metals, MTBE, herbicides, pesticides and chlorinated hydrocarbons.

- Radioactive contamination, resulting from 20th century activities in atomic physics, such as nuclear power generation and nuclear weapons research, manufacture and deployment. (See alpha emitters and actinides in the environment.)

- Thermal pollution, is a temperature change in natural water bodies caused by human influence, such as use of water as coolant in a power plant.

- Visual pollution, which can refer to the presence of overhead power lines, motorway billboards, scarred landforms (as from strip mining), open storage of trash, municipal solid waste or space debris.

- Water pollution, by the discharge of wastewater from commercial and industrial waste (intentionally or through spills) into surface waters; discharges of untreated domestic sewage, and chemical contaminants, such as chlorine, from treated sewage; release of waste and contaminants into surface runoff flowing to surface waters (including urban runoff and agricultural runoff, which may contain chemical fertilizers and pesticides; also including human feces from open defecation – still a major problem in many developing countries); groundwater pollution from waste disposal and leaching into the ground, including from pit latrines and septic tanks; eutrophication and littering.

Pollutants

A pollutant is a waste material that pollutes air, water, or soil.

Three factors determine the severity of a pollutant: its chemical

nature, the concentration and the persistence.

Cost of pollution

Pollution has a cost. Manufacturing activities that cause air pollution

impose health and clean-up costs on the whole of society, whereas the

neighbors of an individual who chooses to fire-proof his home may

benefit from a reduced risk of a fire spreading to their own homes. A

manufacturing activity that causes air pollution is an example of a

negative externality

in production. A negative externality in production occurs “when a

firm’s production reduces the well-being of others who are not

compensated by the firm."

For example, if a laundry firm exists near a polluting steel

manufacturing firm, there will be increased costs for the laundry firm

because of the dirt and smoke produced by the steel manufacturing firm.

If external costs exist, such as those created by pollution, the

manufacturer will choose to produce more of the product than would be

produced if the manufacturer were required to pay all associated

environmental costs. Because responsibility or consequence for

self-directed action lies partly outside the self, an element of externalization is involved. If there are external benefits, such as in public safety,

less of the good may be produced than would be the case if the producer

were to receive payment for the external benefits to others. However,

goods and services that involve negative externalities in production,

such as those that produce pollution, tend to be over-produced and

underpriced since the externality is not being priced into the market.

Pollution can also create costs for the firms producing the

pollution. Sometimes firms choose, or are forced by regulation, to

reduce the amount of pollution that they are producing. The associated

costs of doing this are called abatement costs, or marginal abatement costs if measured by each additional unit. In 2005 pollution abatement capital expenditures and operating costs in the US amounted to nearly $27 billion.

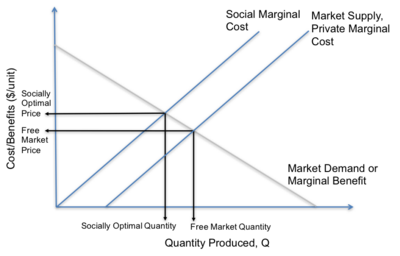

Socially optimal level of pollution

Society derives some indirect utility

from pollution, otherwise there would be no incentive to pollute. This

utility comes from the consumption of goods and services that create

pollution. Therefore, it is important that policymakers attempt to

balance these indirect benefits with the costs of pollution in order to

achieve an efficient outcome.

A visual comparison of the free market and socially optimal outcomes.

It is possible to use environmental economics

to determine which level of pollution is deemed the social optimum. For

economists, pollution is an “external cost and occurs only when one or

more individuals suffer a loss of welfare,” however, there exists a

socially optimal level of pollution at which welfare is maximized. This is because consumers derive utility from the good or service manufactured, which will outweigh the social cost of pollution until a certain point. At this point the damage of one extra unit of pollution to society, the marginal cost of pollution, is exactly equal to the marginal benefit of consuming one more unit of the good or service.

In markets with pollution, or other negative externalities in production, the free market equilibrium will not account for the costs of pollution on society.

If the social costs of pollution are higher than the private costs

incurred by the firm, then the true supply curve will be higher. The

point at which the social marginal cost and market demand

intersect gives the socially optimal level of pollution. At this point,

the quantity will be lower and the price will be higher in comparison

to the free market equilibrium. Therefore, the free market outcome could be considered a market failure because it “does not maximize efficiency”.

This model can be used as a basis to evaluate different methods of internalizing the externality. Some examples include tariffs, a carbon tax and cap and trade systems.

Sources and causes

Air pollution comes from both natural and human-made (anthropogenic)

sources. However, globally human-made pollutants from combustion,

construction, mining, agriculture and warfare are increasingly

significant in the air pollution equation.

Motor vehicle emissions are one of the leading causes of air pollution. China, United States, Russia, India Mexico, and Japan are the world leaders in air pollution emissions. Principal stationary pollution sources include chemical plants, coal-fired power plants, oil refineries, petrochemical plants, nuclear waste disposal activity, incinerators, large livestock farms (dairy cows, pigs, poultry, etc.), PVC factories, metals production factories, plastics factories, and other heavy industry.

Agricultural air pollution comes from contemporary practices which

include clear felling and burning of natural vegetation as well as

spraying of pesticides and herbicides.

About 400 million metric tons of hazardous wastes are generated each year. The United States alone produces about 250 million metric tons. Americans constitute less than 5% of the world's population, but produce roughly 25% of the world’s CO2, and generate approximately 30% of world’s waste. In 2007, China has overtaken the United States as the world's biggest producer of CO2, while still far behind based on per capita pollution – ranked 78th among the world's nations.

In February 2007, a report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change (IPCC), representing the work of 2,500 scientists, economists,

and policymakers from more than 120 countries, said that humans have

been the primary cause of global warming since 1950. Humans have ways to

cut greenhouse gas emissions and avoid the consequences of global

warming, a major climate report concluded. But to change the climate,

the transition from fossil fuels like coal and oil needs to occur within

decades, according to the final report this year from the UN's

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Some of the more common soil contaminants are chlorinated hydrocarbons (CFH), heavy metals (such as chromium, cadmium – found in rechargeable batteries, and lead – found in lead paint, aviation fuel and still in some countries, gasoline), MTBE, zinc, arsenic and benzene. In 2001 a series of press reports culminating in a book called Fateful Harvest

unveiled a widespread practice of recycling industrial byproducts into

fertilizer, resulting in the contamination of the soil with various

metals. Ordinary municipal landfills

are the source of many chemical substances entering the soil

environment (and often groundwater), emanating from the wide variety of

refuse accepted, especially substances illegally discarded there, or

from pre-1970 landfills that may have been subject to little control in

the U.S. or EU. There have also been some unusual releases of polychlorinated dibenzodioxins, commonly called dioxins for simplicity, such as TCDD.

Pollution can also be the consequence of a natural disaster. For example, hurricanes often involve water contamination from sewage, and petrochemical spills from ruptured boats or automobiles. Larger scale and environmental damage is not uncommon when coastal oil rigs or refineries are involved. Some sources of pollution, such as nuclear power plants or oil tankers, can produce widespread and potentially hazardous releases when accidents occur.

In the case of noise pollution the dominant source class is the motor vehicle, producing about ninety percent of all unwanted noise worldwide.

Effects

Human health

Overview of main health effects on humans from some common types of pollution.

Adverse air quality can kill many organisms including humans. Ozone pollution can cause respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, throat inflammation, chest pain, and congestion. Water pollution causes approximately 14,000 deaths per day, mostly due to contamination of drinking water by untreated sewage in developing countries. An estimated 500 million Indians have no access to a proper toilet, Over ten million people in India fell ill with waterborne illnesses in 2013, and 1,535 people died, most of them children. Nearly 500 million Chinese lack access to safe drinking water. A 2010 analysis estimated that 1.2 million people died prematurely each year in China because of air pollution. The high smog levels China has been facing for a long time can do damage to civilians bodies and generate different diseases The WHO estimated in 2007 that air pollution causes half a million deaths per year in India. Studies have estimated that the number of people killed annually in the United States could be over 50,000.

Oil spills can cause skin irritations and rashes. Noise pollution induces hearing loss, high blood pressure, stress, and sleep disturbance. Mercury has been linked to developmental deficits in children and neurologic symptoms. Older people are majorly exposed to diseases induced by air pollution. Those with heart or lung disorders are at additional risk. Children and infants are also at serious risk. Lead and other heavy metals have been shown to cause neurological problems. Chemical and radioactive substances can cause cancer and as well as birth defects.

An October 2017 study by the Lancet Commission on Pollution and

Health found that global pollution, specifically toxic air, water, soils

and workplaces, kill nine million people annually, which is triple the

number of deaths caused by AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria combined, and

15 times higher than deaths caused by wars and other forms of human

violence. The study concluded that "pollution is one of the great existential challenges of the Anthropocene

era. Pollution endangers the stability of the Earth’s support systems

and threatens the continuing survival of human societies."

Environment

Pollution has been found to be present widely in the environment. There are a number of effects of this:

- Biomagnification describes situations where toxins (such as heavy metals) may pass through trophic levels, becoming exponentially more concentrated in the process.

- Carbon dioxide emissions cause ocean acidification, the ongoing decrease in the pH of the Earth's oceans as CO2 becomes dissolved.

- The emission of greenhouse gases leads to global warming which affects ecosystems in many ways.

- Invasive species can out compete native species and reduce biodiversity. Invasive plants can contribute debris and biomolecules (allelopathy) that can alter soil and chemical compositions of an environment, often reducing native species competitiveness.

- Nitrogen oxides are removed from the air by rain and fertilize land which can change the species composition of ecosystems.

- Smog and haze can reduce the amount of sunlight received by plants to carry out photosynthesis and leads to the production of tropospheric ozone which damages plants.

- Soil can become infertile and unsuitable for plants. This will affect other organisms in the food web.

- Sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides can cause acid rain which lowers the pH value of soil.

- Organic pollution of watercourses can deplete oxygen levels and reduce species diversity.

Environmental health information

The Toxicology and Environmental Health Information Program (TEHIP) at the United States National Library of Medicine

(NLM) maintains a comprehensive toxicology and environmental health web

site that includes access to resources produced by TEHIP and by other

government agencies and organizations. This web site includes links to

databases, bibliographies, tutorials, and other scientific and

consumer-oriented resources. TEHIP also is responsible for the

Toxicology Data Network (TOXNET) an integrated system of toxicology and environmental health databases that are available free of charge on the web.

TOXMAP

is a Geographic Information System (GIS) that is part of TOXNET. TOXMAP

uses maps of the United States to help users visually explore data from

the United States Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) Toxics Release Inventory and Superfund Basic Research Programs.

School outcomes

A 2019 paper linked pollution to adverse school outcomes for children.

Worker productivity

A number of studies show that pollution has an adverse effect on the productivity of both indoor and outdoor workers.

Regulation and monitoring

To protect the environment from the adverse effects of pollution,

many nations worldwide have enacted legislation to regulate various

types of pollution as well as to mitigate the adverse effects of

pollution.

Pollution control

A litter trap catches floating waste in the Yarra River, east-central Victoria, Australia

Air pollution control system, known as a Thermal oxidizer, decomposes hazard gases from industrial air streams at a factory in the United States of America.

A dust collector in Pristina, Kosovo

Gas nozzle with vapor recovery

A Mobile Pollution Check Vehicle in India.

Pollution control is a term used in environmental management. It means the control of emissions and effluents into air, water or soil. Without pollution control, the waste products from overconsumption,

heating, agriculture, mining, manufacturing, transportation and other

human activities, whether they accumulate or disperse, will degrade the environment. In the hierarchy of controls, pollution prevention and waste minimization are more desirable than pollution control. In the field of land development, low impact development is a similar technique for the prevention of urban runoff.

Practices

Pollution control devices

- Air pollution control

- Dust collection systems

- Scrubbers

- Sewage treatment

- Sedimentation (Primary treatment)

- Activated sludge biotreaters (Secondary treatment; also used for industrial wastewater)

- Aerated lagoons

- Constructed wetlands (also used for urban runoff)

- Industrial wastewater treatment

- Vapor recovery systems

- Phytoremediation

Perspectives

The earliest precursor of pollution generated by life forms would

have been a natural function of their existence. The attendant

consequences on viability and population levels fell within the sphere

of natural selection.

These would have included the demise of a population locally or

ultimately, species extinction. Processes that were untenable would have

resulted in a new balance brought about by changes and adaptations. At

the extremes, for any form of life, consideration of pollution is

superseded by that of survival.

For humankind, the factor of technology is a distinguishing and

critical consideration, both as an enabler and an additional source of

byproducts. Short of survival, human concerns include the range from

quality of life to health hazards. Since science holds experimental

demonstration to be definitive, modern treatment of toxicity or

environmental harm involves defining a level at which an effect is

observable. Common examples of fields where practical measurement is

crucial include automobile emissions control, industrial exposure (e.g. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) PELs), toxicology (e.g. LD50), and medicine (e.g. medication and radiation doses).

"The solution to pollution is dilution", is a dictum which

summarizes a traditional approach to pollution management whereby

sufficiently diluted pollution is not harmful. It is well-suited to some other modern, locally scoped applications such as laboratory safety procedure and hazardous material

release emergency management. But it assumes that the dilutant is in

virtually unlimited supply for the application or that resulting

dilutions are acceptable in all cases.

Such simple treatment for environmental pollution on a wider

scale might have had greater merit in earlier centuries when physical

survival was often the highest imperative, human population and

densities were lower, technologies were simpler and their byproducts

more benign. But these are often no longer the case. Furthermore,

advances have enabled measurement of concentrations not possible before.

The use of statistical methods in evaluating outcomes has given

currency to the principle of probable harm in cases where assessment is

warranted but resorting to deterministic models is impractical or

infeasible. In addition, consideration of the environment beyond direct

impact on human beings has gained prominence.

Yet in the absence of a superseding principle, this older

approach predominates practices throughout the world. It is the basis by

which to gauge concentrations of effluent for legal release, exceeding

which penalties are assessed or restrictions applied. One such

superseding principle is contained in modern hazardous waste laws in

developed countries, as the process of diluting hazardous waste to make

it non-hazardous is usually a regulated treatment process.

Migration from pollution dilution to elimination in many cases can be

confronted by challenging economical and technological barriers.

Greenhouse gases and global warming

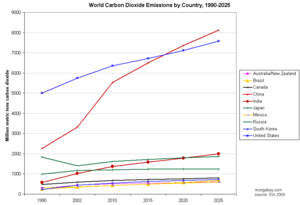

Historical and projected CO2 emissions by country (as of 2005).

Source: Energy Information Administration.

Source: Energy Information Administration.

Carbon dioxide, while vital for photosynthesis,

is sometimes referred to as pollution, because raised levels of the gas

in the atmosphere are affecting the Earth's climate. Disruption of the

environment can also highlight the connection between areas of pollution

that would normally be classified separately, such as those of water

and air. Recent studies have investigated the potential for long-term

rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide to cause slight but critical

increases in the acidity of ocean waters, and the possible effects of this on marine ecosystems.

Most polluting industries

The Pure Earth,

an international non-for-profit organization dedicated to eliminating

life-threatening pollution in the developing world, issues an annual

list of some of the world's most polluting industries.

- Lead-Acid Battery Recycling

- Industrial Mining and Ore Processing

- Lead Smelting

- Tannery Operations

- Artisanal Small-Scale Gold Mining

- Industrial/Municipal Dumpsites

- Industrial Estates

- Chemical Manufacturing

- Product Manufacturing

- Dye Industry

World’s worst polluted places

The Pure Earth issues an annual list of some of the world's worst polluted places.