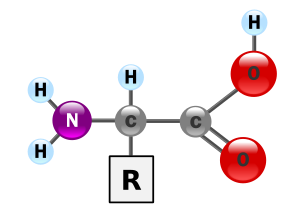

The structure of an alpha amino acid in its un-ionized form

Amino acids are organic compounds containing amine (-NH2) and carboxyl (-COOH) functional groups, along with a side chain (R group) specific to each amino acid. The key elements of an amino acid are carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), and nitrogen

(N), although other elements are found in the side chains of certain

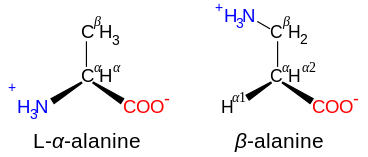

amino acids. About 500 naturally occurring amino acids are known (though

only 20 appear in the genetic code) and can be classified in many ways. They can be classified according to the core structural functional groups' locations as alpha- (α-), beta- (β-), gamma- (γ-) or delta- (δ-) amino acids; other categories relate to polarity, pH level, and side chain group type (aliphatic, acyclic, aromatic, containing hydroxyl or sulfur, etc.). In the form of proteins, amino acid residues form the second-largest component (water is the largest) of human muscles and other tissues. Beyond their role as residues in proteins, amino acids participate in a number of processes such as neurotransmitter transport and biosynthesis.

In biochemistry, amino acids having both the amine and the carboxylic acid groups attached to the first (alpha-) carbon atom have particular importance. They are known as 2-, alpha-, or α-amino acids (generic formula H2NCHRCOOH in most cases, where R is an organic substituent known as a "side chain"); often the term "amino acid" is used to refer specifically to these. They include the 22 proteinogenic ("protein-building") amino acids, which combine into peptide chains ("polypeptides") to form the building-blocks of a vast array of proteins. These are all L-stereoisomers ("left-handed" isomers), although a few D-amino acids ("right-handed") occur in bacterial envelopes, as a neuromodulator (D-serine), and in some antibiotics.

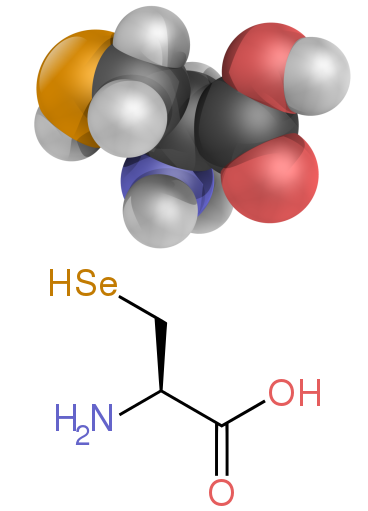

Twenty of the proteinogenic amino acids are encoded directly by triplet codons in the genetic code and are known as "standard" amino acids. The other two ("non-standard" or "non-canonical") are selenocysteine (present in many prokaryotes as well as most eukaryotes, but not coded directly by DNA), and pyrrolysine (found only in some archea and one bacterium). Pyrrolysine and selenocysteine are encoded via variant codons; for example, selenocysteine is encoded by stop codon and SECIS element. N-formylmethionine (which is often the initial amino acid of proteins in bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts) is generally considered as a form of methionine rather than as a separate proteinogenic amino acid. Codon–tRNA combinations not found in nature can also be used to "expand" the genetic code and form novel proteins known as alloproteins incorporating non-proteinogenic amino acids.

Many important proteinogenic and non-proteinogenic amino acids have biological functions. For example, in the human brain, glutamate (standard glutamic acid) and gamma-amino-butyric acid ("GABA", non-standard gamma-amino acid) are, respectively, the main excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters. Hydroxyproline, a major component of the connective tissue collagen, is synthesised from proline. Glycine is a biosynthetic precursor to porphyrins used in red blood cells. Carnitine is used in lipid transport.

Nine proteinogenic amino acids are called "essential" for humans because they cannot be produced from other compounds by the human body and so must be taken in as food. Others may be conditionally essential for certain ages or medical conditions. Essential amino acids may also differ between species.

Because of their biological significance, amino acids are important in nutrition and are commonly used in nutritional supplements, fertilizers, feed, and food technology. Industrial uses include the production of drugs, biodegradable plastics, and chiral catalysts.

History

The first few amino acids were discovered in the early 19th century. In 1806, French chemists Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin and Pierre Jean Robiquet isolated a compound in asparagus that was subsequently named asparagine, the first amino acid to be discovered. Cystine was discovered in 1810, although its monomer, cysteine, remained undiscovered until 1884. Glycine and leucine were discovered in 1820. The last of the 20 common amino acids to be discovered was threonine in 1935 by William Cumming Rose, who also determined the essential amino acids and established the minimum daily requirements of all amino acids for optimal growth.

The unity of the chemical category was recognized by Wurtz in 1865, but he gave no particular name to it. Usage of the term "amino acid" in the English language is from 1898, while the German term, Aminosäure, was used earlier. Proteins were found to yield amino acids after enzymatic digestion or acid hydrolysis. In 1902, Emil Fischer and Franz Hofmeister

independently proposed that proteins are formed from many amino acids,

whereby bonds are formed between the amino group of one amino acid with

the carboxyl group of another, resulting in a linear structure that

Fischer termed "peptide".

General structure

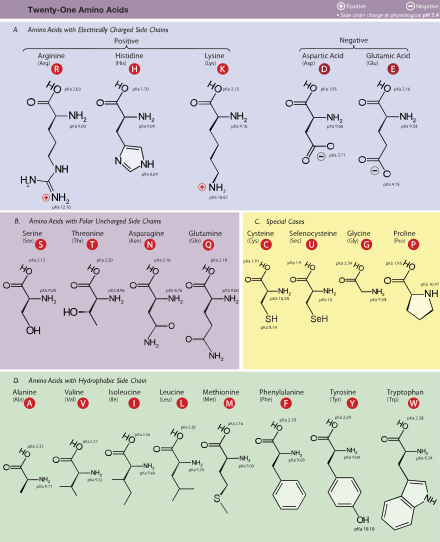

The 21 proteinogenic α-amino acids found in eukaryotes, grouped according to their side chains' pKa values and charges carried at physiological pH (7.4)

In the structure shown at the top of the page, R represents a side chain specific to each amino acid. The carbon atom next to the carboxyl group (which is therefore numbered 2 in the carbon chain starting from that functional group) is called the α–carbon. Amino acids containing an amino group bonded directly to the alpha carbon are referred to as alpha amino acids. These include amino acids such as proline which contain secondary amines, which used to be often referred to as "imino acids".

Isomerism

The alpha amino acids are the most common form found in nature, but only when occurring in the L-isomer. The alpha carbon is a chiral carbon atom, with the exception of glycine which has two indistinguishable hydrogen atoms on the alpha carbon. Therefore, all alpha amino acids but glycine can exist in either of two enantiomers, called L or D amino acids, which are mirror images of each other (see also Chirality). While L-amino acids represent all of the amino acids found in proteins during translation in the ribosome, D-amino acids are found in some proteins produced by enzyme posttranslational modifications after translation and translocation to the endoplasmic reticulum, as in exotic sea-dwelling organisms such as cone snails. They are also abundant components of the peptidoglycan cell walls of bacteria, and D-serine may act as a neurotransmitter in the brain. D-amino acids are used in racemic crystallography

to create centrosymmetric crystals, which (depending on the protein)

may allow for easier and more robust protein structure determination. The L and D

convention for amino acid configuration refers not to the optical

activity of the amino acid itself but rather to the optical activity of

the isomer of glyceraldehyde from which that amino acid can, in theory, be synthesized (D-glyceraldehyde is dextrorotatory; L-glyceraldehyde is levorotatory).

In alternative fashion, the (S) and (R) designators are used to indicate the absolute stereochemistry. Almost all of the amino acids in proteins are (S) at the α carbon, with cysteine being (R) and glycine non-chiral. Cysteine has its side chain in the same geometric position as the other amino acids, but the R/S terminology is reversed because of the higher atomic number of sulfur

compared to the carboxyl oxygen gives the side chain a higher priority,

whereas the atoms in most other side chains give them lower priority.

Side chains

Lysine with carbon atoms labeled by position

In amino acids that have a carbon chain attached to the α–carbon (such as lysine, shown to the right) the carbons are labeled in order as α, β, γ, δ, and so on. In some amino acids, the amine group is attached to the β or γ-carbon, and these are therefore referred to as beta or gamma amino acids.

Amino acids are usually classified by the properties of their side chain into four groups. The side chain can make an amino acid a weak acid or a weak base, and a hydrophile if the side chain is polar or a hydrophobe if it is nonpolar. The chemical structures of the 22 standard amino acids, along with their chemical properties, are described more fully in the article on these proteinogenic amino acids.

The phrase "branched-chain amino acids" or BCAA refers to the amino acids having aliphatic side chains that are non-linear; these are leucine, isoleucine, and valine. Proline is the only proteinogenic

amino acid whose side-group links to the α-amino group and, thus, is

also the only proteinogenic amino acid containing a secondary amine at

this position. In chemical terms, proline is, therefore, an imino acid, since it lacks a primary amino group, although it is still classed as an amino acid in the current biochemical nomenclature, and may also be called an "N-alkylated alpha-amino acid".

Zwitterions

An amino acid in its (1) un-ionized and (2) zwitterionic forms

The α-carboxylic acid group of amino acids is a weak acid, meaning that it releases a hydron (such as a proton) at moderate pH values. In other words, carboxylic acid groups (−CO2H) can be deprotonated to become negative carboxylates (−CO2− ). The negatively charged carboxylate ion predominates at pH values greater than the pKa

of the carboxylic acid group (mean for the 20 common amino acids is

about 2.2, see the table of amino acid structures above). In a

complementary fashion, the α-amine of amino acids is a weak base, meaning that it accepts a proton at moderate pH values. In other words, α-amino groups (NH2−) can be protonated to become positive α-ammonium groups (+NH3−).

The positively charged α-ammonium group predominates at pH values less

than the pKa of the α-ammonium group (mean for the 20 common α-amino

acids is about 9.4).

Because all amino acids contain amine and carboxylic acid functional groups, they share amphiprotic properties.

Below pH 2.2, the predominant form will have a neutral carboxylic acid

group and a positive α-ammonium ion (net charge +1), and above pH 9.4, a

negative carboxylate and neutral α-amino group (net charge −1). But at

pH between 2.2 and 9.4, an amino acid usually contains both a negative

carboxylate and a positive α-ammonium group, as shown in structure (2)

on the right, so has net zero charge. This molecular state is known as a

zwitterion, from the German Zwitter meaning "hermaphrodite" or "hybrid".

The fully neutral form (structure (1) on the left) is a very minor

species in aqueous solution throughout the pH range (less than 1 part in

107). Amino acids exist as zwitterions also in the solid

phase, and crystallize with salt-like properties unlike typical organic

acids or amines.

Isoelectric point

Composite of titration curves of twenty proteinogenic amino acids grouped by side chain category

The variation in titration curves when the amino acids can be grouped by category.[clarification needed] With the exception of tyrosine, using titration to distinguish among hydrophobic amino acids is problematic.

At pH values between the two pKa values, the zwitterion predominates, but coexists in dynamic equilibrium

with small amounts of net negative and net positive ions. At the exact

midpoint between the two pKa values, the trace amount of net negative

and trace of net positive ions exactly balance, so that average net

charge of all forms present is zero. This pH is known as the isoelectric point pI, so pI = ½(pKa1 + pKa2).

The individual amino acids all have slightly different pKa values, so

have different isoelectric points. For amino acids with charged side

chains, the pKa of the side chain is involved. Thus for Asp, Glu with

negative side chains, pI = ½(pKa1 + pKaR), where pKaR is the side chain pKa. Cysteine also has potentially negative side chain with pKaR

= 8.14, so pI should be calculated as for Asp and Glu, even though the

side chain is not significantly charged at neutral pH. For His, Lys, and

Arg with positive side chains, pI = ½(pKaR + pKa2).

Amino acids have zero mobility in electrophoresis at their isoelectric

point, although this behaviour is more usually exploited for peptides

and proteins than single amino acids. Zwitterions have minimum

solubility at their isoelectric point and some amino acids (in

particular, with non-polar side chains) can be isolated by precipitation

from water by adjusting the pH to the required isoelectric point.

Occurrence and functions in biochemistry

The amino acid selenocysteine

Proteinogenic amino acids

Amino acids are the structural units (monomers) that make up proteins. They join together to form short polymer chains called peptides or longer chains called either polypeptides or proteins.

These polymers are linear and unbranched, with each amino acid within

the chain attached to two neighboring amino acids. The process of making

proteins encoded by DNA/RNA genetic material is called translation and involves the step-by-step addition of amino acids to a growing protein chain by a ribozyme that is called a ribosome. The order in which the amino acids are added is read through the genetic code from an mRNA template, which is an RNA copy of one of the organism's genes.

Twenty-two amino acids are naturally incorporated into polypeptides and are called proteinogenic or natural amino acids. Of these, 20 are encoded by the universal genetic code. The remaining 2, selenocysteine and pyrrolysine, are incorporated into proteins by unique synthetic mechanisms. Selenocysteine is incorporated when the mRNA being translated includes a SECIS element, which causes the UGA codon to encode selenocysteine instead of a stop codon. Pyrrolysine is used by some methanogenic archaea in enzymes that they use to produce methane. It is coded for with the codon UAG, which is normally a stop codon in other organisms. This UAG codon is followed by a PYLIS downstream sequence.

Non-proteinogenic amino acids

Aside from the 22 proteinogenic amino acids, many non-proteinogenic amino acids are known. Those either are not found in proteins (for example carnitine, GABA, levothyroxine) or are not produced directly and in isolation by standard cellular machinery (for example, hydroxyproline and selenomethionine).

Non-proteinogenic amino acids that are found in proteins are formed by post-translational modification,

which is modification after translation during protein synthesis. These

modifications are often essential for the function or regulation of a

protein. For example, the carboxylation of glutamate allows for better binding of calcium cations, and collagen contains hydroxyproline, generated by hydroxylation of proline. Another example is the formation of hypusine in the translation initiation factor EIF5A, through modification of a lysine residue.

Such modifications can also determine the localization of the protein,

e.g., the addition of long hydrophobic groups can cause a protein to

bind to a phospholipid membrane.

Some non-proteinogenic amino acids are not found in proteins. Examples include 2-aminoisobutyric acid and the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid. Non-proteinogenic amino acids often occur as intermediates in the metabolic pathways for standard amino acids – for example, ornithine and citrulline occur in the urea cycle, part of amino acid catabolism (see below). A rare exception to the dominance of α-amino acids in biology is the β-amino acid beta alanine (3-aminopropanoic acid), which is used in plants and microorganisms in the synthesis of pantothenic acid (vitamin B5), a component of coenzyme A.

D-amino acid natural abundance

D-isomers are uncommon in live organisms. For instance, gramicidin is a polypeptide made up from mixture of D- and L-amino acids. Other compounds containing D-amino acid are tyrocidine and valinomycin. These compounds disrupt bacterial cell walls, particularly in Gram-positive bacteria. Only 837 D-amino acids were found in Swiss-Prot database (187 million amino acids analyzed).

Non-standard amino acids

The 20 amino acids that are encoded directly by the codons of the universal genetic code are called standard or canonical amino acids. A modified form of methionine (N-formylmethionine)

is often incorporated in place of methionine as the initial amino acid

of proteins in bacteria, mitochondria and chloroplasts. Other amino

acids are called non-standard or non-canonical. Most of

the non-standard amino acids are also non-proteinogenic (i.e. they

cannot be incorporated into proteins during translation), but two of

them are proteinogenic, as they can be incorporated translationally into

proteins by exploiting information not encoded in the universal genetic

code.

The two non-standard proteinogenic amino acids are selenocysteine (present in many non-eukaryotes as well as most eukaryotes, but not coded directly by DNA) and pyrrolysine (found only in some archaea and one bacterium).

The incorporation of these non-standard amino acids is rare. For

example, 25 human proteins include selenocysteine (Sec) in their primary

structure, and the structurally characterized enzymes (selenoenzymes) employ Sec as the catalytic moiety in their active sites. Pyrrolysine and selenocysteine are encoded via variant codons. For example, selenocysteine is encoded by stop codon and SECIS element.

In human nutrition

Share

of amino acid in different human diets and the resulting mix of amino

acids in human blood serum. Glutamate and glutamine are the most

frequent in food at over 10%, while alanine, glutamine, and glycine are

the most common in blood.

When taken up into the human body from the diet, the 20 standard

amino acids either are used to synthesize proteins and other

biomolecules or are oxidized to urea and carbon dioxide as a source of energy. The oxidation pathway starts with the removal of the amino group by a transaminase; the amino group is then fed into the urea cycle. The other product of transamidation is a keto acid that enters the citric acid cycle. Glucogenic amino acids can also be converted into glucose, through gluconeogenesis. Of the 20 standard amino acids, nine (His, Ile, Leu, Lys, Met, Phe, Thr, Trp and Val) are called essential amino acids because the human body cannot synthesize them from other compounds at the level needed for normal growth, so they must be obtained from food. In addition, cysteine, taurine, tyrosine, and arginine

are considered semiessential amino-acids in children (though taurine is

not technically an amino acid), because the metabolic pathways that

synthesize these amino acids are not fully developed.

The amounts required also depend on the age and health of the

individual, so it is hard to make general statements about the dietary

requirement for some amino acids. Dietary exposure to the non-standard

amino acid BMAA has been linked to human neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS.

Diagram of the molecular signaling cascades that are involved in myofibrillar muscle protein synthesis and mitochondrial biogenesis in response to physical exercise and specific amino acids or their derivatives (primarily L-leucine and HMB). Many amino acids derived from food protein promote the activation of mTORC1 and increase protein synthesis by signaling through Rag GTPases.

Resistance

training stimulates muscle protein synthesis (MPS) for a period of up

to 48 hours following exercise (shown by lighter dotted line).

Ingestion of a protein-rich meal at any point during this period will

augment the exercise-induced increase in muscle protein synthesis (shown

by solid lines).

Non-protein functions

In humans, non-protein amino acids also have important roles as metabolic intermediates, such as in the biosynthesis of the neurotransmitter gamma-amino-butyric acid (GABA). Many amino acids are used to synthesize other molecules, for example:

- Tryptophan is a precursor of the neurotransmitter serotonin.

- Tyrosine (and its precursor phenylalanine) are precursors of the catecholamine neurotransmitters dopamine, epinephrine and norepinephrine and various trace amines.

- Phenylalanine is a precursor of phenethylamine and tyrosine in humans. In plants, it is a precursor of various phenylpropanoids, which are important in plant metabolism.

- Glycine is a precursor of porphyrins such as heme.

- Arginine is a precursor of nitric oxide.

- Ornithine and S-adenosylmethionine are precursors of polyamines.

- Aspartate, glycine, and glutamine are precursors of nucleotides. However, not all of the functions of other abundant non-standard amino acids are known.

Some non-standard amino acids are used as defenses against herbivores in plants. For example, canavanine is an analogue of arginine that is found in many legumes, and in particularly large amounts in Canavalia gladiata (sword bean).

This amino acid protects the plants from predators such as insects and

can cause illness in people if some types of legumes are eaten without

processing. The non-protein amino acid mimosine is found in other species of legume, in particular Leucaena leucocephala. This compound is an analogue of tyrosine and can poison animals that graze on these plants.

Uses in industry

Amino acids are used for a variety of applications in industry, but their main use is as additives to animal feed. This is necessary, since many of the bulk components of these feeds, such as soybeans, either have low levels or lack some of the essential amino acids: lysine, methionine, threonine, and tryptophan are most important in the production of these feeds.

In this industry, amino acids are also used to chelate metal cations in

order to improve the absorption of minerals from supplements, which may

be required to improve the health or production of these animals.

The food industry is also a major consumer of amino acids, in particular, glutamic acid, which is used as a flavor enhancer, and aspartame (aspartyl-phenylalanine-1-methyl ester) as a low-calorie artificial sweetener.

Similar technology to that used for animal nutrition is employed in the

human nutrition industry to alleviate symptoms of mineral deficiencies,

such as anemia, by improving mineral absorption and reducing negative

side effects from inorganic mineral supplementation.

The chelating ability of amino acids has been used in fertilizers

for agriculture to facilitate the delivery of minerals to plants in

order to correct mineral deficiencies, such as iron chlorosis. These

fertilizers are also used to prevent deficiencies from occurring and

improving the overall health of the plants. The remaining production of amino acids is used in the synthesis of drugs and cosmetics.

Similarly, some amino acids derivatives are used in pharmaceutical industry. They include 5-HTP (5-hydroxytryptophan) used for experimental treatment of depression, L-DOPA (L-dihydroxyphenylalanine) for Parkinson's treatment, and eflornithine drug that inhibits ornithine decarboxylase and used in the treatment of sleeping sickness.

Expanded genetic code

Since 2001, 40 non-natural amino acids have been added into protein

by creating a unique codon (recoding) and a corresponding

transfer-RNA:aminoacyl – tRNA-synthetase pair to encode it with diverse

physicochemical and biological properties in order to be used as a tool

to exploring protein structure and function or to create novel or enhanced proteins.

Nullomers

Nullomers are codons that in theory code for an amino acid, however

in nature there is a selective bias against using this codon in favor of

another, for example bacteria prefer to use CGA instead of AGA to code

for arginine.

This creates some sequences that do not appear in the genome. This

characteristic can be taken advantage of and used to create new

selective cancer-fighting drugs and to prevent cross-contamination of DNA samples from crime-scene investigations.

Chemical building blocks

Amino acids are important as low-cost feedstocks. These compounds are used in chiral pool synthesis as enantiomerically pure building-blocks.

Amino acids have been investigated as precursors chiral catalysts, e.g., for asymmetric hydrogenation reactions, although no commercial applications exist.

Biodegradable plastics

Amino acids are under development as components of a range of biodegradable polymers. These materials have applications as environmentally friendly packaging and in medicine in drug delivery and the construction of prosthetic implants. These polymers include polypeptides, polyamides,

polyesters, polysulfides, and polyurethanes with amino acids either

forming part of their main chains or bonded as side chains. These

modifications alter the physical properties and reactivities of the

polymers. An interesting example of such materials is polyaspartate, a water-soluble biodegradable polymer that may have applications in disposable diapers and agriculture. Due to its solubility and ability to chelate metal ions, polyaspartate is also being used as a biodegradeable anti-scaling agent and a corrosion inhibitor. In addition, the aromatic amino acid tyrosine is being developed as a possible replacement for toxic phenols such as bisphenol A in the manufacture of polycarbonates.

Reactions

As amino acids have both a primary amine group and a primary carboxyl group, these chemicals can undergo most of the reactions associated with these functional groups. These include nucleophilic addition, amide bond formation, and imine formation for the amine group, and esterification, amide bond formation, and decarboxylation for the carboxylic acid group. The combination of these functional groups allow amino acids to be effective polydentate ligands for metal-amino acid chelates.

The multiple side chains of amino acids can also undergo chemical reactions.

The types of these reactions are determined by the groups on these side

chains and are, therefore, different between the various types of amino

acid.

Chemical synthesis

The Strecker amino acid synthesis

Several methods exist to synthesize amino acids. One of the oldest methods begins with the bromination at the α-carbon of a carboxylic acid. Nucleophilic substitution with ammonia then converts the alkyl bromide to the amino acid. In alternative fashion, the Strecker amino acid synthesis involves the treatment of an aldehyde with potassium cyanide

and ammonia, this produces an α-amino nitrile as an intermediate.

Hydrolysis of the nitrile in acid then yields an α-amino acid.

Using ammonia or ammonium salts in this reaction gives unsubstituted

amino acids, whereas substituting primary and secondary amines will

yield substituted amino acids. Likewise, using ketones, instead of aldehydes, gives α,α-disubstituted amino acids. The classical synthesis gives racemic mixtures of α-amino acids as products, but several alternative procedures using asymmetric auxiliaries or asymmetric catalysts have been developed.

At the current time, the most-adopted method is an automated synthesis on a solid support (e.g., polystyrene beads), using protecting groups (e.g., Fmoc and t-Boc) and activating groups (e.g., DCC and DIC).

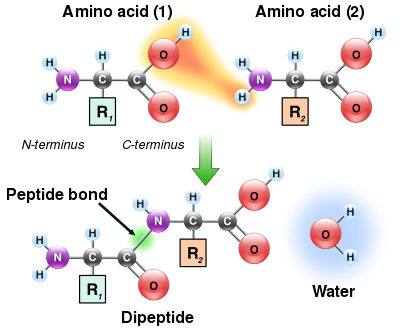

Peptide bond formation

The condensation of two amino acids to form a dipeptide through a peptide bond

As both the amine and carboxylic acid groups of amino acids can react

to form amide bonds, one amino acid molecule can react with another and

become joined through an amide linkage. This polymerization of amino acids is what creates proteins. This condensation reaction yields the newly formed peptide bond

and a molecule of water. In cells, this reaction does not occur

directly; instead, the amino acid is first activated by attachment to a transfer RNA molecule through an ester bond. This aminoacyl-tRNA is produced in an ATP-dependent reaction carried out by an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase. This aminoacyl-tRNA is then a substrate for the ribosome, which catalyzes the attack of the amino group of the elongating protein chain on the ester bond.

As a result of this mechanism, all proteins made by ribosomes are

synthesized starting at their N-terminus and moving toward their

C-terminus.

However, not all peptide bonds are formed in this way. In a few

cases, peptides are synthesized by specific enzymes. For example, the

tripeptide glutathione

is an essential part of the defenses of cells against oxidative stress.

This peptide is synthesized in two steps from free amino acids. In the first step, gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase condenses cysteine and glutamic acid

through a peptide bond formed between the side chain carboxyl of the

glutamate (the gamma carbon of this side chain) and the amino group of

the cysteine. This dipeptide is then condensed with glycine by glutathione synthetase to form glutathione.

In chemistry, peptides are synthesized by a variety of reactions. One of the most-used in solid-phase peptide synthesis

uses the aromatic oxime derivatives of amino acids as activated units.

These are added in sequence onto the growing peptide chain, which is

attached to a solid resin support. The ability to easily synthesize vast numbers of different peptides by varying the types and order of amino acids (using combinatorial chemistry) has made peptide synthesis particularly important in creating libraries of peptides for use in drug discovery through high-throughput screening.

Biosynthesis

In plants, nitrogen is first assimilated into organic compounds in the form of glutamate, formed from alpha-ketoglutarate and ammonia in the mitochondrion. In order to form other amino acids, the plant uses transaminases

to move the amino group to another alpha-keto carboxylic acid. For

example, aspartate aminotransferase converts glutamate and oxaloacetate

to alpha-ketoglutarate and aspartate. Other organisms use transaminases for amino acid synthesis, too.

Nonstandard amino acids are usually formed through modifications to standard amino acids. For example, homocysteine is formed through the transsulfuration pathway or by the demethylation of methionine via the intermediate metabolite S-adenosyl methionine, while hydroxyproline is made by a posttranslational modification of proline.

Microorganisms and plants can synthesize many uncommon amino acids. For example, some microbes make 2-aminoisobutyric acid and lanthionine, which is a sulfide-bridged derivative of alanine. Both of these amino acids are found in peptidic lantibiotics such as alamethicin. However, in plants, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid is a small disubstituted cyclic amino acid that is a key intermediate in the production of the plant hormone ethylene.

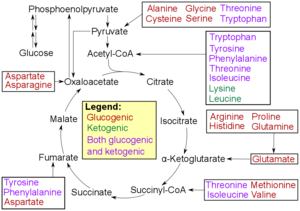

Catabolism

Catabolism

of proteinogenic amino acids. Amino acids can be classified according

to the properties of their main products as either of the following:

* Glucogenic, with the products having the ability to form glucose by gluconeogenesis

* Ketogenic, with the products not having the ability to form glucose. These products may still be used for ketogenesis or lipid synthesis.

* Amino acids catabolized into both glucogenic and ketogenic products.

* Glucogenic, with the products having the ability to form glucose by gluconeogenesis

* Ketogenic, with the products not having the ability to form glucose. These products may still be used for ketogenesis or lipid synthesis.

* Amino acids catabolized into both glucogenic and ketogenic products.

Amino acids must first pass out of organelles and cells into blood circulation via amino acid transporters,

since the amine and carboxylic acid groups are typically ionized.

Degradation of an amino acid, occurring in the liver and kidneys, often

involves deamination by moving its amino group to alpha-ketoglutarate, forming glutamate.

This process involves transaminases, often the same as those used in

amination during synthesis. In many vertebrates, the amino group is then

removed through the urea cycle and is excreted in the form of urea. However, amino acid degradation can produce uric acid or ammonia instead. For example, serine dehydratase converts serine to pyruvate and ammonia.

After removal of one or more amino groups, the remainder of the

molecule can sometimes be used to synthesize new amino acids, or it can

be used for energy by entering glycolysis or the citric acid cycle, as detailed in image at right.

Physicochemical properties of amino acids

The

20 amino acids encoded directly by the genetic code can be divided into

several groups based on their properties. Important factors are charge,

hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity, size, and functional groups. These properties are important for protein structure and protein–protein interactions.

The water-soluble proteins tend to have their hydrophobic residues

(Leu, Ile, Val, Phe, and Trp) buried in the middle of the protein,

whereas hydrophilic side chains are exposed to the aqueous solvent.

(Note that in biochemistry, a residue refers to a specific monomer within the polymeric chain of a polysaccharide, protein or nucleic acid.) The integral membrane proteins tend to have outer rings of exposed hydrophobic amino acids that anchor them into the lipid bilayer. In the case part-way between these two extremes, some peripheral membrane proteins

have a patch of hydrophobic amino acids on their surface that locks

onto the membrane. In similar fashion, proteins that have to bind to

positively charged molecules have surfaces rich with negatively charged

amino acids like glutamate and aspartate, while proteins binding to negatively charged molecules have surfaces rich with positively charged chains like lysine and arginine. There are different hydrophobicity scales of amino acid residues.

Some amino acids have special properties such as cysteine, that can form covalent disulfide bonds to other cysteine residues, proline that forms a cycle to the polypeptide backbone, and glycine that is more flexible than other amino acids.

Many proteins undergo a range of posttranslational modifications, when additional chemical groups are attached to the amino acids in proteins. Some modifications can produce hydrophobic lipoproteins, or hydrophilic glycoproteins.

These type of modification allow the reversible targeting of a protein

to a membrane. For example, the addition and removal of the fatty acid palmitic acid to cysteine residues in some signaling proteins causes the proteins to attach and then detach from cell membranes.

![Amine reaction with carboxylic acids {\displaystyle {\underbrace {\ce {H-\!\!{\overset {\displaystyle R1 \atop |}{\underset {| \atop \displaystyle R2}{N}}}\!\!\!\!:}} _{amine}+\underbrace {\ce {R3-{\overset {\displaystyle O \atop \|}{C}}-OH}} _{\text{carboxylic acid}}->}\ \underbrace {\ce {{H-{\overset {\displaystyle R1 \atop |}{\underset {| \atop \displaystyle R2}{N+}}}-H}+R3-COO^{-}}} _{{\text{substituted-ammonium}} \atop {\text{carboxylate salt}}}{\ce {->[heat][dehydration]}}{\underbrace {\ce {{\overset {\displaystyle R1 \atop |}{\underset {| \atop \displaystyle R2}{N}}}\!\!-{\overset {\displaystyle O \atop \|}{C}}-R3}} _{amide}+\underbrace {\ce {H2O}} _{water}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ed9e4ee62efb585271572cbf0fd9149c90a400fd)