Paleoclimatology is the study of changes in climate taken on the scale of the entire history of Earth. It uses a variety of proxy methods from the Earth and life sciences to obtain data previously preserved within things such as rocks, sediments, ice sheets, tree rings, corals, shells, and microfossils. It then uses the records to determine the past states of the Earth's various climate regions and its atmospheric

system. Studies of past changes in the environment and biodiversity

often reflect on the current situation, specifically the impact of

climate on mass extinctions and biotic recovery.

History

The scientific study field of paleoclimate began to form in the early

19th century, when discoveries about glaciations and natural changes in

Earth's past climate helped to understand the greenhouse effect.The

first observations which had a real scientific basis were probably

those by John Hardcastle in New Zealand, in the 1880s. He noted that the

loess deposits at Timaru in the South Island recorded changes in climate; he called the loess a 'climate register'.

Reconstructing ancient climates

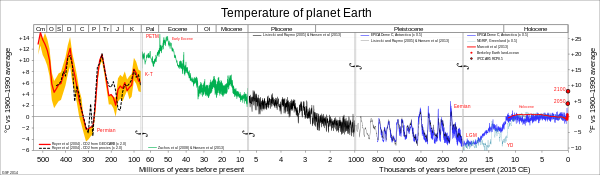

Palaeotemperature graphs compressed together

The oxygen content in the atmosphere over the last billion years

Paleoclimatologists employ a wide variety of techniques to deduce ancient climates.

Ice

Mountain glaciers and the polar ice caps/ice sheets provide much data in paleoclimatology. Ice-coring projects in the ice caps of Greenland and Antarctica have yielded data going back several hundred thousand years, over 800,000 years in the case of the EPICA project.

- Air trapped within fallen snow becomes encased in tiny bubbles as the snow is compressed into ice in the glacier under the weight of later years' snow. The trapped air has proven a tremendously valuable source for direct measurement of the composition of air from the time the ice was formed.

- Layering can be observed because of seasonal pauses in ice accumulation and can be used to establish chronology, associating specific depths of the core with ranges of time.

- Changes in the layering thickness can be used to determine changes in precipitation or temperature.

- Oxygen-18 quantity changes (δ18O) in ice layers represent changes in average ocean surface temperature. Water molecules containing the heavier O-18 evaporate at a higher temperature than water molecules containing the normal Oxygen-16 isotope. The ratio of O-18 to O-16 will be higher as temperature increases. It also depends on other factors such as the water's salinity and the volume of water locked up in ice sheets. Various cycles in those isotope ratios have been detected.

- Pollen has been observed in the ice cores and can be used to understand which plants were present as the layer formed. Pollen is produced in abundance and its distribution is typically well understood. A pollen count for a specific layer can be produced by observing the total amount of pollen categorized by type (shape) in a controlled sample of that layer. Changes in plant frequency over time can be plotted through statistical analysis of pollen counts in the core. Knowing which plants were present leads to an understanding of precipitation and temperature, and types of fauna present. Palynology includes the study of pollen for these purposes.

- Volcanic ash is contained in some layers, and can be used to establish the time of the layer's formation. Each volcanic event distributed ash with a unique set of properties (shape and color of particles, chemical signature). Establishing the ash's source will establish a range of time to associate with layer of ice.

Dendroclimatology

Climatic information can be obtained through an understanding of

changes in tree growth. Generally, trees respond to changes in climatic

variables by speeding up or slowing down growth, which in turn is

generally reflected by a greater or lesser thickness in growth rings.

Different species, however, respond to changes in climatic variables in

different ways. A tree-ring record is established by compiling

information from many living trees in a specific area.

Older intact wood that has escaped decay can extend the time

covered by the record by matching the ring depth changes to contemporary

specimens. By using that method, some areas have tree-ring records

dating back a few thousand years. Older wood not connected to a

contemporary record can be dated generally with radiocarbon techniques. A

tree-ring record can be used to produce information regarding

precipitation, temperature, hydrology, and fire corresponding to a

particular area.

Sedimentary content

On a longer time scale, geologists must refer to the sedimentary record for data.

- Sediments, sometimes lithified to form rock, may contain remnants of preserved vegetation, animals, plankton, or pollen, which may be characteristic of certain climatic zones.

- Biomarker molecules such as the alkenones may yield information about their temperature of formation.

- Chemical signatures, particularly Mg/Ca ratio of calcite in Foraminifera tests, can be used to reconstruct past temperature.

- Isotopic ratios can provide further information. Specifically, the δ18O record responds to changes in temperature and ice volume, and the δ13C record reflects a range of factors, which are often difficult to disentangle.

Sea

floor core sample labelled to identify the exact spot on the sea floor

where the sample was taken. Sediments from nearby locations can show

significant differences in chemical and biological composition.

- Sedimentary facies

- On a longer time scale, the rock record may show signs of sea level rise and fall, and features such as "fossilised" sand dunes can be identified. Scientists can get a grasp of long term climate by studying sedimentary rock going back billions of years. The division of earth history into separate periods is largely based on visible changes in sedimentary rock layers that demarcate major changes in conditions. Often, they include major shifts in climate.

Sclerochronology

- Corals (see also sclerochronology)

- Coral "rings" are similar to tree rings except that they respond to different things, such as the water temperature, freshwater influx, pH changes, and wave action. From there, certain equipment can be used to derive the sea surface temperature and water salinity from the past few centuries. The δ18O of coralline red algae provides a useful proxy of the combined sea surface temperature and sea surface salinity at high latitudes and the tropics, where many traditional techniques are limited.

Landscapes and landforms

Within climatic geomorphology one approach is to study relict landforms to infer ancient climates. Being often concerned about past climates climatic geomorphology is considered sometimes to be a theme of historical geology. Climatic geomorphology is of limited use to study recent (Quaternary, Holocene) large climate changes since there are seldom discernible in the geomorphological record.

Time Scale and Limitations

A multinational consortium, the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA), has drilled an ice core in Dome C on the East Antarctic ice sheet and retrieved ice from roughly 800,000 years ago.

The international ice core community has, under the auspices of

International Partnerships in Ice Core Sciences (IPICS), defined a

priority project to obtain the oldest possible ice core record from

Antarctica, an ice core record reaching back to or towards 1.5 million

years ago.

The deep marine record, the source of most isotopic data, exists only

on oceanic plates, which are eventually subducted: the oldest remaining

material is 200 million years old. Older sediments are also more prone to corruption by diagenesis. Resolution and confidence in the data decrease over time.

Notable climate events in Earth history

Knowledge of precise climatic events decreases as the record goes back in time, but some notable climate events are known:

- Faint young Sun paradox (start)

- Huronian glaciation (~2400 Mya Earth completely covered in ice probably due to Great Oxygenation Event)

- Later Neoproterozoic Snowball Earth (~600 Mya, precursor to the Cambrian Explosion)

- Andean-Saharan glaciation (~450 Mya)

- Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse (~300 Mya)

- Permian–Triassic extinction event (251.4 Mya)

- Oceanic anoxic events (~120 Mya, 93 Mya, and others)

- Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (66 Mya)

- Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (Paleocene–Eocene, 55Mya)

- Younger Dryas/The Big Freeze (~11,000 BC)

- Holocene climatic optimum (~7000–3000 BC)

- Extreme weather events of 535–536 (535–536 AD)

- Medieval Warm Period (900–1300)

- Little Ice Age (1300–1800)

- Year Without a Summer (1816)

History of the atmosphere

Earliest atmosphere

The first atmosphere would have consisted of gases in the solar nebula, primarily hydrogen. In addition, there would probably have been simple hydrides such as those now found in gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn, notably water vapor, methane, and ammonia. As the solar nebula dissipated, the gases would have escaped, partly driven off by the solar wind.

Second atmosphere

The next atmosphere, consisting largely of nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and inert gases, was produced by outgassing from volcanism, supplemented by gases produced during the late heavy bombardment of Earth by huge asteroids. A major part of carbon dioxide emissions were soon dissolved in water and built up carbonate sediments.

Water-related sediments have been found dating from as early as 3.8 billion years ago.

About 3.4 billion years ago, nitrogen was the major part of the then

stable "second atmosphere". An influence of life has to be taken into

account rather soon in the history of the atmosphere because hints of

early life forms have been dated to as early as 3.5 billion years ago.

The fact that it is not perfectly in line with the 30% lower solar

radiance (compared to today) of the early Sun has been described as the "faint young Sun paradox".

The geological record, however, shows a continually relatively warm surface during the complete early temperature record of Earth with the exception of one cold glacial phase about 2.4 billion years ago. In the late Archaean eon, an oxygen-containing atmosphere began to develop, apparently from photosynthesizing cyanobacteria which have been found as stromatolite fossils from 2.7 billion years ago. The early basic carbon isotopy (isotope ratio proportions) was very much in line with what is found today, suggesting that the fundamental features of the carbon cycle were established as early as 4 billion years ago.

Third atmosphere

The constant rearrangement of continents by plate tectonics

influences the long-term evolution of the atmosphere by transferring

carbon dioxide to and from large continental carbonate stores. Free

oxygen did not exist in the atmosphere until about 2.4 billion years

ago, during the Great Oxygenation Event, and its appearance is indicated by the end of the banded iron formations.

Until then, any oxygen produced by photosynthesis was consumed by

oxidation of reduced materials, notably iron. Molecules of free oxygen

did not start to accumulate in the atmosphere until the rate of

production of oxygen began to exceed the availability of reducing

materials. That point was a shift from a reducing atmosphere to an oxidizing atmosphere. O2 showed major variations until reaching a steady state of more than 15% by the end of the Precambrian. The following time span was the Phanerozoic eon, during which oxygen-breathing metazoan life forms began to appear.

The amount of oxygen in the atmosphere has fluctuated over the last 600 million years, reaching a peak of 35% during the Carboniferous period, significantly higher than today's 21%. Two main processes govern changes in the atmosphere: plants use carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, releasing oxygen and the breakdown of pyrite and volcanic eruptions release sulfur

into the atmosphere, which oxidizes and hence reduces the amount of

oxygen in the atmosphere. However, volcanic eruptions also release

carbon dioxide, which plants can convert to oxygen. The exact cause of

the variation of the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere is not known.

Periods with much oxygen in the atmosphere are associated with rapid

development of animals. Today's atmosphere contains 21% oxygen, which is

high enough for rapid development of animals.

Climate during geological ages

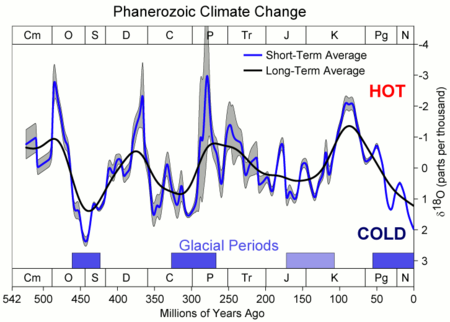

Timeline of glaciations, shown in blue

- The Huronian glaciation, is the first known glaciation in Earth's history, and lasted from 2400-2100 million years ago.

- The Cryogenian glaciation lasted from 720-635 million years ago.

- The Andean-Saharan glaciation lasted from 450–420 million years ago.

- The Karoo glaciation lasted from 360–260 million years ago.

- The Quaternary glaciation is the current glaciation period and began 2.58 million years ago.

Precambrian climate

The climate of the late Precambrian showed some major glaciation events spreading over much of the earth. At this time the continents were bunched up in the Rodinia supercontinent. Massive deposits of tillites and anomalous isotopic signatures are found, which gave rise to the Snowball Earth hypothesis. As the Proterozoic Eon

drew to a close, the Earth started to warm up. By the dawn of the

Cambrian and the Phanerozoic, life forms were abundant in the Cambrian explosion with average global temperatures of about 22 °C.

Phanerozoic climate

500 million years of climate change

Major drivers for the preindustrial ages have been variations of the

sun, volcanic ashes and exhalations, relative movements of the earth

towards the sun, and tectonically induced effects as for major sea

currents, watersheds, and ocean oscillations. In the early Phanerozoic,

increased atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations have been linked to

driving or amplifying increased global temperatures. Royer et al. 2004

found a climate sensitivity for the rest of the Phanerozoic which was

calculated to be similar to today's modern range of values.

The difference in global mean temperatures between a fully

glacial Earth and an ice free Earth is estimated at approximately 10 °C,

though far larger changes would be observed at high latitudes and

smaller ones at low latitudes.

One requirement for the development of large scale ice sheets seems to

be the arrangement of continental land masses at or near the poles. The

constant rearrangement of continents by plate tectonics

can also shape long-term climate evolution. However, the presence or

absence of land masses at the poles is not sufficient to guarantee

glaciations or exclude polar ice caps. Evidence exists of past warm

periods in Earth's climate when polar land masses similar to Antarctica were home to deciduous forests rather than ice sheets.

The relatively warm local minimum between Jurassic and Cretaceous goes along with an increase of subduction and mid-ocean ridge volcanism due to the breakup of the Pangea supercontinent.

Superimposed on the long-term evolution between hot and cold

climates have been many short-term fluctuations in climate similar to,

and sometimes more severe than, the varying glacial and interglacial

states of the present ice age. Some of the most severe fluctuations, such as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, may be related to rapid climate changes due to sudden collapses of natural methane clathrate reservoirs in the oceans.

A similar, single event of induced severe climate change after a meteorite impact has been proposed as reason for the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. Other major thresholds are the Permian-Triassic, and Ordovician-Silurian extinction events with various reasons suggested.

Quaternary climate

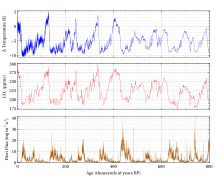

Ice

core data for the past 800,000 years (x-axis values represent "age

before 1950", so today's date is on the left side of the graph and older

time on the right). Blue curve is temperature, red curve is atmospheric CO2 concentrations, and brown curve is dust fluxes. Note length of glacial-interglacial cycles averages ~100,000 years.

The Quaternary sub-era includes the current climate. There has been a cycle of ice ages for the past 2.2–2.1 million years (starting before the Quaternary in the late Neogene Period).

Note in the graphic on the right the strong 120,000-year

periodicity of the cycles, and the striking asymmetry of the curves.

This asymmetry is believed to result from complex interactions of

feedback mechanisms. It has been observed that ice ages deepen by

progressive steps, but the recovery to interglacial conditions occurs in

one big step.

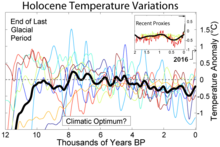

Holocene Temperature Variations

The graph on the left shows the temperature change over the past

12,000 years, from various sources. The thick black curve is an average.

Climate forcings

Radiative forcings, IPCC (2007)

Climate forcing is the difference between radiant energy (sunlight) received by the Earth and the outgoing longwave radiation back to space. Radiative forcing is quantified based on the CO2 amount in the tropopause, in units of watts per square meter to the Earth's surface. Dependent on the radiative balance

of incoming and outgoing energy, the Earth either warms up or cools

down. Earth radiative balance originates from changes in solar insolation and the concentrations of greenhouse gases and aerosols. Climate change may be due to internal processes in Earth sphere's and/or following external forcings.

Internal processes and forcings

The Earth's climate system involves the atmosphere, biosphere, cryosphere, hydrosphere, and lithosphere,

and the sum of these processes from Earth's spheres is what affects the

climate. Greenhouse gasses act as the internal forcing of the climate

system. Particular interests in climate science and paleoclimatology

focus on the study of Earth climate sensitivity, in response to the sum of forcings.

Examples:

- Thermohaline circulation (Hydrosphere)

- Life (Biosphere)

External forcings

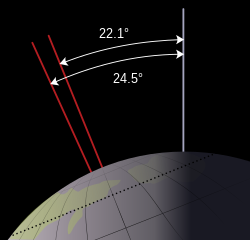

- The Milankovitch cycles determine Earth distance and position to the Sun. The solar insolation is the total amount of solar radiation received by Earth.

- Volcanic eruptions are considered an external forcing.

- Human changes of the composition of the atmosphere or land use.

Mechanisms

On timescales of millions of years, the uplift of mountain ranges and subsequent weathering processes of rocks and soils and the subduction of tectonic plates, are an important part of the carbon cycle. The weathering sequesters CO2, by the reaction of minerals with chemicals (especially silicate weathering with CO2) and thereby removing CO2 from the atmosphere and reducing the radiative forcing. The opposite effect is volcanism, responsible for the natural greenhouse effect, by emitting CO2 into the atmosphere, thus affecting glaciation (Ice Age) cycles.

Ice sheet

dynamics and continental positions (and linked vegetation changes) have

been important factors in the long term evolution of the earth's

climate. There is also a close correlation between CO2 and temperature, where CO2 has a strong control over global temperatures in Earth history.