| Confucianism | |

| Chinese name | |

|---|---|

| Chinese | 儒家 |

| Literal meaning | "ru school of thought" |

| Vietnamese name | |

|---|---|

| Vietnamese alphabet | Nho giáo |

| Chữ Hán | 儒教 |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 유교 |

| Hanja | 儒教 |

| Japanese name | |

|---|---|

| Kanji | 儒教 |

| Kana | じゅきょう |

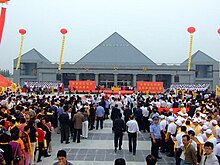

Temple of Confucius of Jiangyin, Wuxi, Jiangsu. This is a wénmiào (文庙), that is to say a temple where Confucius is worshipped as Wéndì (文帝), "God of Culture".

Confucianism, also known as Ruism, is described as

tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic

religion, a way of governing, or simply a way of life. Confucianism developed from what was later called the Hundred Schools of Thought from the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE), who considered himself a recodifier and retransmitter of the theology and values inherited from the Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE) and Zhou dynasties (c. 1046–256 BCE). In the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), Confucian approaches edged out the "proto-Taoist" Huang–Lao as the official ideology, while the emperors mixed both with the realist techniques of Legalism.

A Confucian revival began during the Tang dynasty (618–907). In the late Tang, Confucianism developed in response to Buddhism and Taoism and was reformulated as Neo-Confucianism. This reinvigorated form was adopted as the basis of the imperial exams and the core philosophy of the scholar official class in the Song dynasty (960–1297). The abolition of the examination system in 1905 marked the end of official Confucianism. The intellectuals of the New Culture Movement

of the early twentieth century blamed Confucianism for China's

weaknesses. They searched for new doctrines to replace Confucian

teachings; some of these new ideologies include the "Three Principles of the People" with the establishment of the Republic of China, and then Maoism under the People's Republic of China. In the late twentieth century Confucian work ethic has been credited with the rise of the East Asian economy.

With particular emphasis on the importance of the family and

social harmony, rather than on an otherworldly source of spiritual

values, the core of Confucianism is humanistic. According to Herbert Fingarette's conceptualisation of Confucianism as a religion which regards "the secular as sacred",

Confucianism transcends the dichotomy between religion and humanism,

considering the ordinary activities of human life—and especially human

relationships—as a manifestation of the sacred, because they are the expression of humanity's moral nature (xìng 性), which has a transcendent anchorage in Heaven (Tiān 天) and unfolds through an appropriate respect for the spirits or gods (shén) of the world. While Tiān has some characteristics that overlap the category of godhead, it is primarily an impersonal absolute principle, like the Dào (道) or the Brahman. Confucianism focuses on the practical order that is given by a this-worldly awareness of the Tiān. Confucian liturgy (called 儒 rú, or sometimes 正統/正统 zhèngtǒng, meaning 'orthoprax') led by Confucian priests or "sages of rites" (禮生/礼生 lǐshēng) to worship the gods in public and ancestral Chinese temples is preferred on certain occasions, by Confucian religious groups and for civil religious rites, over Taoist or popular ritual.

The worldly concern of Confucianism rests upon the belief that

human beings are fundamentally good, and teachable, improvable, and

perfectible through personal and communal endeavor, especially

self-cultivation and self-creation. Confucian thought focuses on the

cultivation of virtue in a morally organised world. Some of the basic

Confucian ethical concepts and practices include rén, yì, and lǐ, and zhì. Rén

(仁, 'benevolence' or 'humaneness') is the essence of the human being

which manifests as compassion. It is the virtue-form of Heaven. Yì (義/义) is the upholding of righteousness and the moral disposition to do good. Lǐ

(禮/礼) is a system of ritual norms and propriety that determines how a

person should properly act in everyday life in harmony with the law of

Heaven. Zhì (智) is the ability to see what is right and fair, or

the converse, in the behaviors exhibited by others. Confucianism holds

one in contempt, either passively or actively, for failure to uphold the

cardinal moral values of rén and yì.

Traditionally, cultures and countries in the Chinese cultural sphere are strongly influenced by Confucianism, including mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, as well as various territories settled predominantly by Chinese people, such as Singapore. Today, it has been credited for shaping East Asian societies and Chinese communities, and to some extent, other parts of Asia. In the last decades there have been talks of a "Confucian Revival" in the academic and the scholarly community, and there has been a grassroots proliferation of various types of Confucian churches. In late 2015 many Confucian personalities formally established a national Holy Confucian Church (孔聖會/孔圣会 Kǒngshènghuì) in China to unify the many Confucian congregations and civil society organisations.

Terminology

Olden versions of the grapheme 儒 rú, meaning "scholar", "refined one", "Confucian". It is composed of 人 rén ("man") and 需 xū ("to await"), itself composed of 雨 yǔ ("rain", "instruction") and 而 ér ("sky"), graphically a "man under the rain". Its full meaning is "man receiving instruction from Heaven". According to Kang Youwei, Hu Shih, and Yao Xinzhong, they were the official shaman-priests (wu) experts in rites and astronomy of the Shang, and later Zhou, dynasty.

Strictly speaking, there is no term in Chinese which directly

corresponds to "Confucianism". In the Chinese language, the character rú

儒 meaning "scholar" or "learned" or "refined man" is generally used

both in the past and the present to refer to things related to

Confucianism. The character rú in ancient China had diverse meanings. Some examples include "to tame", "to mould", "to educate", "to refine".

Several different terms, some of which with modern origin, are used in

different situations to express different facets of Confucianism,

including:

- Chinese: 儒 家; pinyin: Rújiā – "ru school of thought";

- Chinese: 儒 教; pinyin: Rújiào – "ru religion" in the sense of "ru doctrine";

- traditional Chinese: 儒 學; simplified Chinese: 儒 学; pinyin: Rúxué – "Ruology" or "ru learning";

- Chinese: 孔 教; pinyin: Kǒngjiào – "Confucius's doctrine";

- Chinese: 孔 家 店; pinyin: Kǒngjiādiàn – "Kong family's business", a pejorative phrase used in the New Culture Movement and the Cultural Revolution.

Three of them use rú. These names do not use the name

"Confucius" at all, but instead focus on the ideal of the Confucian man.

The use of the term "Confucianism" has been avoided by some modern

scholars, who favor "Ruism" and "Ruists" instead. Robert Eno argues that

the term has been "burdened... with the ambiguities and irrelevant

traditional associations". Ruism, as he states, is more faithful to the

original Chinese name for the school.

According to Zhou Youguang, 儒 rú

originally referred to shamanic methods of holding rites and existed

before Confucius's times, but with Confucius it came to mean devotion to

propagating such teachings to bring civilisation to the people.

Confucianism was initiated by Confucius, developed by Mencius

(~372–289 BCE) and inherited by later generations, undergoing constant

transformations and restructuring since its establishment, but

preserving the principles of humaneness and righteousness at its core.

Five Classics (五经, Wǔjīng) and the Confucian vision

Confucius in a fresco from a Western Han tomb in Dongping, Shandong

Traditionally, Confucius was thought to be the author or editor of the Five Classics which were the basic texts of Confucianism. The scholar Yao Xinzhong

allows that there are good reasons to believe that Confucian classics

took shape in the hands of Confucius, but that "nothing can be taken for

granted in the matter of the early versions of the classics". Professor

Yao says that perhaps most scholars today hold the "pragmatic" view

that Confucius and his followers, although they did not intend to create

a system of classics, "contributed to their formation". In any case, it

is undisputed that for most of the last 2,000 years, Confucius was

believed to have either written or edited these texts.

The scholar Tu Weiming explains these classics as embodying "five visions" which underlie the development of Confucianism:

- I Ching or Classic of Change or Book of Changes, generally held to be the earliest of the classics, shows a metaphysical vision which combines divinatory art with numerological technique and ethical insight; philosophy of change sees cosmos as interaction between the two energies yin and yang; universe always shows organismic unity and dynamism.

- Classic of Poetry or Book of Songs is the earliest anthology of Chinese poems and songs. It shows the poetic vision in the belief that poetry and music convey common human feelings and mutual responsiveness.

- Book of Documents or Book of History Compilation of speeches of major figures and records of events in ancient times embodies the political vision and addresses the kingly way in terms of the ethical foundation for humane government. The documents show the sagacity, filial piety, and work ethic of Yao, Shun, and Yu. They established a political culture which was based on responsibility and trust. Their virtue formed a covenant of social harmony which did not depend on punishment or coercion.

- Book of Rites describes the social forms, administration, and ceremonial rites of the Zhou Dynasty. This social vision defined society not as an adversarial system based on contractual relations but as a community of trust based on social responsibility. The four functional occupations are cooperative (farmer, scholar, artisan, merchant).

- Spring and Autumn Annals chronicles the period to which it gives its name, Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BCE) and these events emphasise the significance of collective memory for communal self-identification, for reanimating the old is the best way to attain the new.

Doctrines

Theory and theology

Zhou dynasty oracular version of the grapheme for Tiān, representing a man with a head informed by the north celestial pole

Confucianism revolves around the pursuit of the unity of the individual self and the God of Heaven (Tiān 天), or, otherwise said, around the relationship between humanity and Heaven. The principle of Heaven (Lǐ 理 or Dào 道), is the order of the creation and the source of divine authority, monistic in its structure. Individuals may realise their humanity and become one with Heaven through the contemplation of such order. This transformation of the self may be extended to the family and society to create a harmonious fiduciary community. Joël Thoraval studied Confucianism as a diffused civil religion

in contemporary China, finding that it expresses itself in the

widespread worship of five cosmological entities: Heaven and Earth (Di 地), the sovereign or the government (jūn 君), ancestors (qīn 親) and masters (shī 師).

Heaven is not some being pre-existing the temporal world. According to the scholar Stephan Feuchtwang, in Chinese cosmology, which is not merely Confucian but shared by all Chinese religions, "the universe creates itself out of a primary chaos of material energy" (hundun 混沌 and qi 氣), organising through the polarity of yin and yang which characterises any thing and life. Creation is therefore a continuous ordering; it is not a creation ex nihilo.

Yin and yang are the invisible and visible, the receptive and the

active, the unshaped and the shaped; they characterise the yearly cycle

(winter and summer), the landscape (shady and bright), the sexes (female

and male), and even sociopolitical history (disorder and order).

Confucianism is concerned with finding "middle ways" between yin and

yang at every new configuration of the world.

Confucianism conciliates both the inner and outer polarities of

spiritual cultivation, that is to say self-cultivation and world

redemption, synthesised in the ideal of "sageliness within and

kingliness without". Rén,

translated as "humaneness" or the essence proper of a human being, is

the character of compassionate mind; it is the virtue endowed by Heaven

and at the same time the means by which man may achieve oneness with

Heaven comprehending his own origin in Heaven and therefore divine

essence. In the Dàtóng shū (《大同書/大同书》) it is defined as "to form

one body with all things" and "when the self and others are not

separated ... compassion is aroused".

Tiān and the gods

Like other symbols such as the swastika, wàn 卍 ("all things") in Chinese, the Mesopotamian 𒀭 Dingir/An ("Heaven"), and also the Chinese 巫 wū ("shaman"; in Shang script represented by the cross potent ☩), Tiān refers to the northern celestial pole (北極 Běijí), the pivot and the vault of the sky with its spinning constellations. Here is an approximate representation of the Tiānmén 天門 ("Gate of Heaven") or Tiānshū 天樞 ("Pivot of Heaven") as the precessional north celestial pole, with α Ursae Minoris as the pole star, with the spinning Chariot constellations in the four phases of time. According to Reza Assasi's theories, the wan may not only be centred in the current precessional pole at α Ursae Minoris, but also very near to the north ecliptic pole if Draco (Tiānlóng 天龙) is conceived as one of its two beams.

Tiān (天), a key concept in Chinese thought, refers to the God of Heaven, the northern culmen of the skies and its spinning stars,

earthly nature and its laws which come from Heaven, to "Heaven and

Earth" (that is, "all things"), and to the awe-inspiring forces beyond

human control. There are such a number of uses in Chinese thought that it is not possible to give one translation into English.

Confucius used the term in a mystical way. He wrote in the Analects

(7.23) that Tian gave him life, and that Tian watched and judged (6.28;

9.12). In 9.5 Confucius says that a person may know the movements of

the Tian, and this provides with the sense of having a special place in

the universe. In 17.19 Confucius says that Tian spoke to him, though not

in words. The scholar Ronnie Littlejohn warns that Tian has not to be

interpreted as personal God comparable to that of the Abrahamic faiths,

in the sense of an otherworldly or transcendent creator. Rather it is similar to what Taoists meant by Dao: "the way things are" or "the regularities of the world", which Stephan Feuchtwang equates with the ancient Greek concept of physis, "nature" as the generation and regenerations of things and of the moral order. Tian may also be compared to the Brahman of Hindu and Vedic traditions.

The scholar Promise Hsu, in the wake of Robert B. Louden, explained

17:19 ("What does Tian ever say? Yet there are four seasons going round

and there are the hundred things coming into being. What does Tian

say?") as implying that even though Tian is not a "speaking person", it

constantly "does" through the rhythms of nature, and communicates "how

human beings ought to live and act", at least to those who have learnt

to carefully listen to it.

Zigong,

a disciple of Confucius, said that Tian had set the master on the path

to become a wise man (9.6). In 7.23 Confucius says that he has no doubt

left that the Tian gave him life, and from it he had developed right

virtue (德 dé). In 8.19 he says that the lives of the sages are interwoven with Tian.

Regarding personal gods (shén, energies who emanate from and reproduce the Tian) enliving nature, in the Analects Confucius says that it is appropriate (義/义 yì) for people to worship (敬 jìng) them, though through proper rites (禮/礼 lǐ), implying respect of positions and discretion. Confucius himself was a ritual and sacrificial master.

Answering to a disciple who asked whether it is better to sacrifice to

the god of the stove or to the god of the family (a popular saying), in

3.13 Confucius says that in order to appropriately pray gods one should

first know and respect Heaven. In 3.12 he explains that religious

rituals produce meaningful experiences,

and one has to offer sacrifices in person, acting in presence,

otherwise "it is the same as not having sacrificed at all". Rites and

sacrifices to the gods have an ethical importance: they generate good life, because taking part in them leads to the overcoming of the self.

Analects 10.11 tells that Confucius always took a small part of his

food and placed it on the sacrificial bowls as an offering to his ancestors.

Other movements, such as Mohism which was later absorbed by Taoism, developed a more theistic idea of Heaven.

Feuchtwang explains that the difference between Confucianism and Taoism

primarily lies in the fact that the former focuses on the realisation

of the starry order of Heaven in human society, while the latter on the

contemplation of the Dao which spontaneously arises in nature.

Social morality and ethics

Worship at the Great Temple of Lord Zhang Hui (张挥公大殿 Zhāng Huī gōng dàdiàn), the cathedral ancestral shrine of the Zhang lineage corporation, at their ancestral home in Qinghe, Hebei

As explained by Stephan Feuchtwang, the order coming from Heaven

preserves the world, and has to be followed by humanity finding a

"middle way" between yin and yang forces in each new configuration of

reality. Social harmony or morality is identified as patriarchy, which

is expressed in the worship of ancestors and deified progenitors in the

male line, at ancestral shrines.

Confucian ethical codes are described as humanistic.

They may be practiced by all the members of a society. Confucian ethics

is characterised by the promotion of virtues, encompassed by the Five

Constants, Wǔcháng (五常) in Chinese, elaborated by Confucian scholars out of the inherited tradition during the Han dynasty. The Five Constants are:

- Rén (仁, benevolence, humaneness);

- Yì (義/义, righteousness or justice);

- Lǐ (禮/礼, proper rite);

- Zhì (智, knowledge);

- Xìn (信, integrity).

These are accompanied by the classical Sìzì (四字), that singles out four virtues, one of which is included among the Five Constants:

- Zhōng (忠, loyalty);

- Xiào (孝, filial piety);

- Jié (節/节, contingency);

- Yì (義/义, righteousness).

There are still many other elements, such as chéng (誠/诚, honesty), shù (恕, kindness and forgiveness), lián (廉, honesty and cleanness), chǐ (恥/耻, shame, judge and sense of right and wrong), yǒng (勇, bravery), wēn (溫/温, kind and gentle), liáng (良, good, kindhearted), gōng (恭, respectful, reverent), jiǎn (儉/俭, frugal), ràng (讓/让, modestly, self-effacing).

Humaneness

Rén (Chinese: 仁) is the Confucian virtue denoting the good feeling a virtuous human experiences when being altruistic.

It is exemplified by a normal adult's protective feelings for children.

It is considered the essence of the human being, endowed by Heaven, and

at the same time the means by which man may act according to the

principle of Heaven (天理, Tiān lǐ) and become one with it.

Yán Huí, Confucius's most outstanding student, once asked his master to describe the rules of rén and Confucius replied, "one should see nothing improper, hear nothing improper, say nothing improper, do nothing improper." Confucius also defined rén

in the following way: "wishing to be established himself, seeks also to

establish others; wishing to be enlarged himself, he seeks also to

enlarge others."

Another meaning of rén is "not to do to others as you would not wish done to yourself." Confucius also said, "rén is not far off; he who seeks it has already found it." Rén is close to man and never leaves him.

Rite and centering

Temple of Confucius in Dujiangyan, Chengdu, Sichuan

Korean Confucian rite in Jeju

Li (禮/礼) is a classical Chinese word which finds its most extensive use in Confucian and post-Confucian Chinese philosophy. Li is variously translated as "rite" or "reason," "ratio" in the pure sense of Vedic ṛta ("right," "order") when referring to the cosmic law, but when referring to its realisation in the context of human social behaviour it has also been translated as "customs", "measures" and "rules", among other terms. Li also means religious rites which establish relations between humanity and the gods.

According to Stephan Feuchtwang, rites are conceived as "what

makes the invisible visible", making possible for humans to cultivate

the underlying order of nature. Correctly performed rituals move society

in alignment with earthly and heavenly (astral) forces, establishing

the harmony of the three realms—Heaven, Earth and humanity. This

practice is defined as "centering" (央 yāng or 中 zhōng).

Among all things of creation, humans themselves are "central" because

they have the ability to cultivate and centre natural forces.

Li embodies the entire web of interaction between humanity, human objects, and nature. Confucius includes in his discussions of li such diverse topics as learning, tea drinking, titles, mourning, and governance. Xunzi

cites "songs and laughter, weeping and lamentation... rice and millet,

fish and meat... the wearing of ceremonial caps, embroidered robes, and

patterned silks, or of fasting clothes and mourning clothes... spacious

rooms and secluded halls, soft mats, couches and benches" as vital parts

of the fabric of li.

Confucius envisioned proper government being guided by the principles of li. Some Confucians proposed that all human beings may pursue perfection by learning and practising li. Overall, Confucians believe that governments should place more emphasis on li and rely much less on penal punishment when they govern.

Loyalty

Loyalty (Chinese: 忠, zhōng)

is particularly relevant for the social class to which most of

Confucius's students belonged, because the most important way for an

ambitious young scholar to become a prominent official was to enter a

ruler's civil service.

Confucius himself did not propose that "might makes right," but

rather that a superior should be obeyed because of his moral rectitude.

In addition, loyalty does not mean subservience to authority. This is

because reciprocity is demanded from the superior as well. As Confucius

stated "a prince should employ his minister according to the rules of

propriety; ministers should serve their prince with faithfulness

(loyalty)."

Similarly, Mencius

also said that "when the prince regards his ministers as his hands and

feet, his ministers regard their prince as their belly and heart; when

he regards them as his dogs and horses, they regard him as another man;

when he regards them as the ground or as grass, they regard him as a

robber and an enemy."

Moreover, Mencius indicated that if the ruler is incompetent, he should

be replaced. If the ruler is evil, then the people have the right to

overthrow him. A good Confucian is also expected to remonstrate with his superiors when necessary.

At the same time, a proper Confucian ruler should also accept his

ministers' advice, as this will help him govern the realm better.

In later ages, however, emphasis was often placed more on the

obligations of the ruled to the ruler, and less on the ruler's

obligations to the ruled. Like filial piety, loyalty was often subverted

by the autocratic regimes in China. Nonetheless, throughout the ages,

many Confucians continued to fight against unrighteous superiors and

rulers. Many of these Confucians suffered and sometimes died because of

their conviction and action. During the Ming-Qing era, prominent Confucians such as Wang Yangming promoted individuality and independent thinking as a counterweight to subservience to authority.

The famous thinker Huang Zongxi also strongly criticised the autocratic

nature of the imperial system and wanted to keep imperial power in

check.

Many Confucians also realised that loyalty and filial piety have

the potential of coming into conflict with one another. This may be true

especially in times of social chaos, such as during the period of the

Ming-Qing transition.

Filial piety

Fourteenth of The Twenty-four Filial Exemplars

In Confucian philosophy, filial piety (Chinese: 孝, xiào)

is a virtue of respect for one's parents and ancestors, and of the

hierarchies within society: father–son, elder–junior and male–female. The Confucian classic Xiaojing

("Book of Piety"), thought to be written around the Qin-Han period, has

historically been the authoritative source on the Confucian tenet of xiào. The book, a conversation between Confucius and his student Zeng Shen (曾參, also known as Zengzi 曾子), is about how to set up a good society using the principle of xiào.

In more general terms, filial piety means to be good to one's

parents; to take care of one's parents; to engage in good conduct not

just towards parents but also outside the home so as to bring a good

name to one's parents and ancestors; to perform the duties of one's job

well so as to obtain the material means to support parents as well as

carry out sacrifices to the ancestors; not be rebellious;

show love, respect and support; display courtesy; ensure male heirs,

uphold fraternity among brothers; wisely advise one's parents, including

dissuading them from moral unrighteousness, for blindly following the

parents' wishes is not considered to be xiao; display sorrow for their sickness and death; and carry out sacrifices after their death.

Filial piety is considered a key virtue in Chinese culture, and it is the main concern of a large number of stories. One of the most famous collections of such stories is "The Twenty-four Filial Exemplars" (Ershi-si xiao 二十四孝).

These stories depict how children exercised their filial piety in the

past. While China has always had a diversity of religious beliefs,

filial piety has been common to almost all of them; historian Hugh D.R.

Baker calls respect for the family the only element common to almost all

Chinese believers.

Relationships

Social harmony results in part from every individual knowing his or

her place in the natural order, and playing his or her part well.

Reciprocity or responsibility (renqing) extends beyond filial piety and involves the entire network of social relations, even the respect for rulers. When Duke Jing of Qi asked about government, by which he meant proper administration so as to bring social harmony, Confucius replied:

There is government, when the prince is prince, and the minister is minister; when the father is father, and the son is son. (Analects XII, 11, tr. Legge)

Particular duties arise from one's particular situation in relation

to others. The individual stands simultaneously in several different

relationships with different people: as a junior in relation to parents

and elders, and as a senior in relation to younger siblings, students,

and others. While juniors are considered in Confucianism to owe their

seniors reverence, seniors also have duties of benevolence and concern

toward juniors. The same is true with the husband and wife relationship

where the husband needs to show benevolence towards his wife and the

wife needs to respect the husband in return. This theme of mutuality

still exists in East Asian cultures even to this day.

The Five Bonds are: ruler to ruled, father to son, husband to

wife, elder brother to younger brother, friend to friend. Specific

duties were prescribed to each of the participants in these sets of

relationships. Such duties are also extended to the dead, where the

living stand as sons to their deceased family. The only relationship

where respect for elders isn't stressed was the friend to friend

relationship, where mutual equal respect is emphasised instead. All

these duties take the practical form of prescribed rituals, for instance

wedding and death rituals.

Junzi

The junzi (Chinese: 君子, jūnzǐ, "lord's son") is a Chinese philosophical term often translated as "gentleman" or "superior person" and employed by Confucius in his works to describe the ideal man. In the I Ching it is used by the Duke of Wen.

In Confucianism, the sage or wise is the ideal personality;

however, it is very hard to become one of them. Confucius created the

model of junzi, gentleman, which may be achieved by any individual. Later, Zhu Xi defined junzi as second only to the sage. There are many characteristics of the junzi: he may live in poverty, he does more and speaks less, he is loyal, obedient and knowledgeable. The junzi disciplines himself. Ren is fundamental to become a junzi.

As the potential leader of a nation, a son of the ruler is raised

to have a superior ethical and moral position while gaining inner peace

through his virtue. To Confucius, the junzi sustained the

functions of government and social stratification through his ethical

values. Despite its literal meaning, any righteous man willing to

improve himself may become a junzi.

On the contrary, the xiaoren (小人, xiăorén, "small or petty person") does not grasp the value of virtues and seeks only immediate gains. The petty person is egotistic and does not consider the consequences of his action in the overall scheme of things. Should the ruler be surrounded by xiaoren as opposed to junzi, his governance and his people will suffer due to their small-mindness. Examples of such xiaoren individuals may range from those who continually indulge in sensual and emotional pleasures all day to the politician who is interested merely in power and fame; neither sincerely aims for the long-term benefit of others.

The junzi enforces his rule over his subjects by acting virtuously himself. It is thought that his pure virtue would lead others to follow his example. The ultimate goal is that the government behaves much like a family, the junzi being a beacon of filial piety.

Rectification of names

Priest paying homage to Confucius's tablet, c. 1900

Confucius believed that social disorder often stemmed from failure to perceive, understand, and deal with reality.

Fundamentally, then, social disorder may stem from the failure to call

things by their proper names, and his solution to this was zhèngmíng (Chinese: 正名; pinyin: zhèngmíng; literally: 'rectification of terms'). He gave an explanation of zhengming to one of his disciples.

Zi-lu said, "The vassal of Wei has been waiting for you, in order with you to administer the government. What will you consider the first thing to be done?"

The Master replied, "What is necessary to rectify names."

"So! indeed!" said Zi-lu. "You are wide off the mark! Why must there be such rectification?"

The Master said, "How uncultivated you are, Yu! The superior man [Junzi] cannot care about the everything, just as he cannot go to check all himself!

If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things.

If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.

When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music do not flourish.

When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be properly awarded.

When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know how to move hand or foot.

Therefore a superior man considers it necessary that the names he uses may be spoken appropriately, and also that what he speaks may be carried out appropriately. What the superior man requires is just that in his words there may be nothing incorrect."

(Analects XIII, 3, tr. Legge)

Xun Zi chapter (22) "On the Rectification of Names" claims the ancient sage-kings chose names (Chinese: 名; pinyin: míng) that directly corresponded with actualities (Chinese: 實; pinyin: shí),

but later generations confused terminology, coined new nomenclature,

and thus could no longer distinguish right from wrong. Since social harmony

is of utmost importance, without the proper rectification of names,

society would essentially crumble and "undertakings [would] not [be]

completed."

History

The dragon is one of the oldest symbols of Chinese religious culture. It symbolises the supreme godhead, Di or Tian, at the north ecliptic pole, around which it coils itself as the homonymous constellation. It is a symbol of the "protean" supreme power which has in itself both yin and yang.

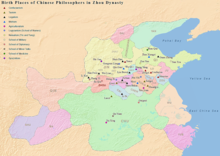

Birth

places of notable Chinese philosophers of the Hundred Schools of

Thought in Zhou dynasty. Confucians are marked by triangles in dark red.

According to He Guanghu, Confucianism may be identified as a continuation of the Shang-Zhou (~1600–256 BCE) official religion, or the Chinese aboriginal religion which has lasted uninterrupted for three thousand years. Both the dynasties worshipped the supreme godhead, called Shangdi (上帝 "Highest Deity") or simply Dì (帝) by the Shang and Tian (天 "Heaven") by the Zhou. Shangdi was conceived as the first ancestor of the Shang royal house, an alternate name for him being the "Supreme Progenitor" (上甲 Shàngjiǎ). In Shang theology, the multiplicity of gods of nature and ancestors were viewed as parts of Di, and the four 方 fāng ("directions" or "sides") and their 風 fēng ("winds") as his cosmic will. With the Zhou dynasty, which overthrew the Shang, the name for the supreme godhead became Tian (天 "Heaven").

While the Shang identified Shangdi as their ancestor-god to assert

their claim to power by divine right, the Zhou transformed this claim

into a legitimacy based on moral power, the Mandate of Heaven.

In Zhou theology, Tian had no singular earthly progeny, but bestowed

divine favour on virtuous rulers. Zhou kings declared that their victory

over the Shang was because they were virtuous and loved their people,

while the Shang were tyrants and thus were deprived of power by Tian.

John C. Didier and David Pankenier relate the shapes of both the ancient Chinese characters

for Di and Tian to the patterns of stars in the northern skies, either

drawn, in Didier's theory by connecting the constellations bracketing

the north celestial pole as a square, or in Pankenier's theory by connecting some of the stars which form the constellations of the Big Dipper and broader Ursa Major, and Ursa Minor (Little Dipper).

Cultures in other parts of the world have also conceived these stars or

constellations as symbols of the origin of things, the supreme godhead,

divinity and royal power. The supreme godhead was also identified with the dragon, symbol of unlimited power (qi), of the "protean" primordial power which embodies both yin and yang in unity, associated to the constellation Draco which winds around the north ecliptic pole, and slithers between the Little and Big Dipper.

By the 6th century BCE the power of Tian and the symbols that

represented it on earth (architecture of cities, temples, altars and

ritual cauldrons, and the Zhou ritual system) became "diffuse" and

claimed by different potentates in the Zhou states to legitimise

economic, political, and military ambitions. Divine right no longer was

an exclusive privilege of the Zhou royal house, but might be bought by

anyone able to afford the elaborate ceremonies and the old and new rites

required to access the authority of Tian.

Besides the waning Zhou ritual system, what may be defined as "wild" (野 yě)

traditions, or traditions "outside of the official system", developed

as attempts to access the will of Tian. The population had lost faith in

the official tradition, which was no longer perceived as an effective

way to communicate with Heaven. The traditions of the 九野 ("Nine Fields")

and of the Yijing flourished. Chinese thinkers, faced with this challenge to legitimacy, diverged in a "Hundred Schools of Thought", each proposing its own theories for the reconstruction of the Zhou moral order.

Confucius

(551–479 BCE) appeared in this period of political decadence and

spiritual questioning. He was educated in Shang-Zhou theology, which he

contributed to transmit and reformulate giving centrality to

self-cultivation and agency of humans, and the educational power of the self-established individual in assisting others to establish themselves (the principle of 愛人 àirén, "loving others").

As the Zhou reign collapsed, traditional values were abandoned

resulting in a period of moral decline. Confucius saw an opportunity to

reinforce values of compassion and tradition into society. Disillusioned

with the widespread vulgarisation of the rituals to access Tian, he

began to preach an ethical interpretation of traditional Zhou religion.

In his view, the power of Tian is immanent, and responds positively to

the sincere heart driven by humaneness and rightness, decency and

altruism. Confucius conceived these qualities as the foundation needed

to restore socio-political harmony. Like many contemporaries, Confucius

saw ritual practices as efficacious ways to access Tian, but he thought

that the crucial knot was the state of meditation that participants enter prior to engage in the ritual acts. Confucius amended and recodified the classical books inherited from the Xia-Shang-Zhou dynasties, and composed the Spring and Autumn Annals.

Philosophers in the Warring States period,

both "inside the square" (focused on state-endorsed ritual) and

"outside the square" (non-aligned to state ritual) built upon

Confucius's legacy, compiled in the Analects,

and formulated the classical metaphysics that became the lash of

Confucianism. In accordance with the Master, they identified mental

tranquility as the state of Tian, or the One (一 Yī), which in

each individual is the Heaven-bestowed divine power to rule one's own

life and the world. Going beyond the Master, they theorised the oneness

of production and reabsorption into the cosmic source, and the

possibility to understand and therefore reattain it through meditation.

This line of thought would have influenced all Chinese individual and

collective-political mystical theories and practices thereafter.

Organisation and liturgy

Temple of the Filial Blessing (孝佑宫 Xiàoyòugōng), an ancestral temple of a lineage church, in Wenzhou, Zhejiang

Since the 2000s, there has been a growing identification of the Chinese intellectual class with Confucianism.

In 2003, the Confucian intellectual Kang Xiaoguang published a

manifesto in which he made four suggestions: Confucian education should

enter official education at any level, from elementary to high school;

the state should establish Confucianism as the state religion by law;

Confucian religion should enter the daily life of ordinary people

through standardisation and development of doctrines, rituals,

organisations, churches and activity sites; the Confucian religion

should be spread through non-governmental organisations. Another modern proponent of the institutionalisation of Confucianism in a state church is Jiang Qing.

In 2005, the Center for the Study of Confucian Religion was established, and guoxue

started to be implemented in public schools on all levels. Being well

received by the population, even Confucian preachers have appeared on

television since 2006.

The most enthusiastic New Confucians proclaim the uniqueness and

superiority of Confucian Chinese culture, and have generated some

popular sentiment against Western cultural influences in China.

The idea of a "Confucian Church" as the state religion of China has roots in the thought of Kang Youwei,

an exponent of the early New Confucian search for a regeneration of the

social relevance of Confucianism, at a time when it was

de-institutionalised with the collapse of the Qing dynasty and the Chinese empire.

Kang modeled his ideal "Confucian Church" after European national

Christian churches, as a hierarchic and centralised institution, closely

bound to the state, with local church branches, devoted to the worship

and the spread of the teachings of Confucius.

In contemporary China, the Confucian revival has developed into

various interwoven directions: the proliferation of Confucian schools or

academies (shuyuan 书院), the resurgence of Confucian rites (chuántǒng lǐyí 传统礼仪), and the birth of new forms of Confucian activity on the popular level, such as the Confucian communities (shèqū rúxué 社区儒学). Some scholars also consider the reconstruction of lineage churches and their ancestral temples,

as well as cults and temples of natural and national gods within

broader Chinese traditional religion, as part of the renewal of

Confucianism.

Other forms of revival are salvationist folk religious movements groups with a specifically Confucian focus, or Confucian churches, for example the Yidan xuetang (一耽学堂) of Beijing, the Mengmutang (孟母堂) of Shanghai, Confucian Shenism (儒宗神教 Rúzōng Shénjiào) or the phoenix churches, the Confucian Fellowship (儒教道坛 Rújiào Dàotán) in northern Fujian which has spread rapidly over the years after its foundation, and ancestral temples of the Kong kin (the lineage of the descendants of Confucius himself) operating as Confucian-teaching churches.

Also, the Hong Kong Confucian Academy,

one of the direct heirs of Kang Youwei's Confucian Church, has expanded

its activities to the mainland, with the construction of statues of

Confucius, Confucian hospitals, restoration of temples and other

activities.

In 2009, Zhou Beichen founded another institution which inherits the

idea of Kang Youwei's Confucian Church, the Holy Hall of Confucius (孔圣堂 Kǒngshèngtáng) in Shenzhen, affiliated with the Federation of Confucian Culture of Qufu City. It was the first of a nationwide movement of congregations and civil organisations that was unified in 2015 in the Holy Confucian Church (孔圣会 Kǒngshènghuì). The first spiritual leader of the Holy Church is the renowned scholar Jiang Qing, the founder and manager of the Yangming Confucian Abode (阳明精舍 Yángmíng jīngshě), a Confucian academy in Guiyang, Guizhou.

Chinese folk religious temples and kinship ancestral shrines may, on peculiar occasions, choose Confucian liturgy (called 儒 rú or 正统 zhèngtǒng, "orthoprax") led by Confucian ritual masters (礼生 lǐshēng) to worship the gods, instead of Taoist or popular ritual. "Confucian businessmen" (儒商人 rúshāngrén,

also "refined businessman") is a recently rediscovered concept defining

people of the economic-entrepreneurial elite who recognise their social

responsibility and therefore apply Confucian culture to their business.

Governance

Yushima Seidō in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan

To govern by virtue, let us compare it to the North Star: it stays in its place, while the myriad stars wait upon it. (Analects 2.1)

A key Confucian concept is that in order to govern others one must

first govern oneself according to the universal order. When actual, the

king's personal virtue (de) spreads beneficent influence throughout the kingdom. This idea is developed further in the Great Learning, and is tightly linked with the Taoist concept of wu wei (simplified Chinese: 无为; traditional Chinese: 無為; pinyin: wú wéi):

the less the king does, the more gets done. By being the "calm center"

around which the kingdom turns, the king allows everything to function

smoothly and avoids having to tamper with the individual parts of the

whole.

This idea may be traced back to the ancient shamanic beliefs of the king being the axle between the sky, human beings, and the Earth. The emperors of China were considered agents of Heaven, endowed with the Mandate of Heaven.

They hold the power to define the hierarchy of divinities, by bestowing

titles upon mountains, rivers and dead people, acknowledging them as

powerful and therefore establishing their cults.

Meritocracy

In teaching, there should be no distinction of classes. (Analects 15.39)

Although Confucius claimed that he never invented anything but was only transmitting ancient knowledge (Analects 7.1), he did produce a number of new ideas. Many European and American admirers such as Voltaire and H.G. Creel point to the revolutionary idea of replacing nobility of blood with nobility of virtue. Jūnzǐ

(君子, lit. "lord's child"), which originally signified the younger,

non-inheriting, offspring of a noble, became, in Confucius's work, an

epithet having much the same meaning and evolution as the English

"gentleman."

A virtuous commoner who cultivates his qualities may be a

"gentleman", while a shameless son of the king is only a "small man."

That he admitted students of different classes as disciples is a clear

demonstration that he fought against the feudal structures that defined

pre-imperial Chinese society.

Another new idea, that of meritocracy, led to the introduction of the imperial examination

system in China. This system allowed anyone who passed an examination

to become a government officer, a position which would bring wealth and

honour to the whole family. The Chinese imperial examination system

started in the Sui dynasty.

Over the following centuries the system grew until finally almost

anyone who wished to become an official had to prove his worth by

passing a set of written government examinations. The practice of

meritocracy still exists today in across China and East Asia today.

Influence

In 17th-century Europe

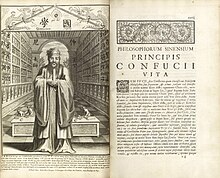

"Life and works of Confucius, by Prospero Intorcetta, 1687

The works of Confucius were translated into European languages through the agency of Jesuit scholars stationed in China. Matteo Ricci was among the very earliest to report on the thoughts of Confucius, and father Prospero Intorcetta wrote about the life and works of Confucius in Latin in 1687.

Translations of Confucian texts influenced European thinkers of the period, particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Western civilisation.

Confucianism influenced Gottfried Leibniz,

who was attracted to the philosophy because of its perceived similarity

to his own. It is postulated that certain elements of Leibniz's

philosophy, such as "simple substance" and "preestablished harmony,"

were borrowed from his interactions with Confucianism. The French philosopher Voltaire was also influenced by Confucius, seeing the concept of Confucian rationalism as an alternative to Christian dogma. He praised Confucian ethics and politics, portraying the sociopolitical hierarchy of China as a model for Europe.

Confucius has no interest in falsehood; he did not pretend to be prophet; he claimed no inspiration; he taught no new religion; he used no delusions; flattered not the emperor under whom he lived...

— Voltaire

On Islamic thought

From the late 17th century onwards a whole body of literature known as the Han Kitab developed amongst the Hui Muslims of China who infused Islamic thought with Confucianism. Especially the works of Liu Zhi such as Tiānfāng Diǎnlǐ(天方典禮)sought to harmonise Islam with not only Confucianism but also with Taoism and is considered to be one of the crowning achievements of the Chinese Islamic culture.

In modern times

Important military and political figures in modern Chinese history

continued to be influenced by Confucianism, like the Muslim warlord Ma Fuxiang. The New Life Movement in the early 20th century was also influenced by Confucianism.

Referred to variously as the Confucian hypothesis and as a

debated component of the more all-encompassing Asian Development Model,

there exists among political scientists and economists a theory that

Confucianism plays a large latent role in the ostensibly non-Confucian

cultures of modern-day East Asia, in the form of the rigorous work ethic

it endowed those cultures with. These scholars have held that, if not

for Confucianism's influence on these cultures, many of the people of

the East Asia region would not have been able to modernise and

industrialise as quickly as Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and even China have done.

For example, the impact of the Vietnam War

on Vietnam was devastating, but over the last few decades Vietnam has

been re-developing in a very fast pace. Most scholars attribute the

origins of this idea to futurologist Herman Kahn's World Economic Development: 1979 and Beyond.

Other studies, for example Cristobal Kay's Why East Asia Overtook Latin America: Agrarian Reform, Industrialization, and Development,

have attributed the Asian growth to other factors, for example the

character of agrarian reforms, "state-craft" (state capacity), and

interaction between agriculture and industry.

On Chinese martial arts

After Confucianism had become the official 'state religion' in China,

its influence penetrated all walks of life and all streams of thought

in Chinese society for the generations to come. This did not exclude

martial arts culture. Though in his own day, Confucius had rejected the

practice of Martial Arts (with the exception of Archery), he did serve

under rulers who used military power extensively to achieve their goals.

In later centuries, Confucianism heavily influenced many educated

martial artists of great influence, such as Sun Lutang,

especially from the 19th century onwards, when bare-handed martial arts

in China became more widespread and had begun to more readily absorb

philosophical influences from Confucianism, Buddhism and Daoism. Some argue therefore that despite Confucius's disdain with martial culture, his teachings became of much relevance to it.

Criticism

Confucius and Confucianism were opposed or criticised from the start, including Laozi's philosophy and Mozi's critique, and Legalists such as Han Fei

ridiculed the idea that virtue would lead people to be orderly. In

modern times, waves of opposition and vilification showed that

Confucianism, instead of taking credit for the glories of Chinese

civilisation, now had to take blame for its failures. The Taiping Rebellion described Confucianism sages as well as gods in Taoism and Buddhism as devils. In the New Culture Movement, Lu Xun criticised Confucianism for shaping Chinese people into the condition they had reached by the late Qing Dynasty: his criticisms are dramatically portrayed in "A Madman's Diary," which implies that Confucian society was cannibalistic. Leftists during the Cultural Revolution described Confucius as the representative of the class of slave owners.

In South Korea,

there has long been criticism. Some South Koreans believe Confucianism

has not contributed to the modernisation of South Korea. For example,

South Korean writer Kim Kyong-il wrote an essay entitled "Confucius Must Die For the Nation to Live" (공자가 죽어야 나라가 산다, gongjaga jug-eoya naraga sanda). Kim said that filial piety

is one-sided and blind, and if it continues social problems will

continue as government keeps forcing Confucian filial obligations onto

families.

Women in Confucian thought

Confucianism "largely defined the mainstream discourse on gender in China from the Han dynasty onward." The gender roles prescribed in the Three Obediences and Four Virtues

became a cornerstone of the family, and thus, societal stability.

Starting from the Han period, Confucians began to teach that a virtuous

woman was supposed to follow the males in her family: the father before

her marriage, the husband after she marries, and her sons in widowhood.

In the later dynasties, more emphasis was placed on the virtue of

chastity. The Song dynasty Confucian Cheng Yi stated that: "To starve to death is a small matter, but to lose one's chastity is a great matter." Chaste widows were revered and memorialised during the Ming and Qing periods. This "cult of chastity" accordingly condemned many widows to poverty and loneliness by placing a social stigma on remarriage.

For years, many modern scholars have regarded Confucianism as a

sexist, patriarchal ideology that was historically damaging to Chinese

women.

It has also been argued by some Chinese and Western writers that the

rise of neo-Confucianism during the Song dynasty had led to a decline of

status of women. Some critics have also accused the prominent Song neo-Confucian scholar Zhu Xi for believing in the inferiority of women and that men and women need to be kept strictly separate, while Sima Guang also believed that women should remain indoor and not deal with the matters of men in the outside world. Finally, scholars have discussed the attitudes toward women in Confucian texts such as Analects. In a much-discussed passage, women are grouped together with xiaoren

(小人, literally "small people", meaning people of low status or low

moral) and described as being difficult to cultivate or deal with.

Many traditional commentators and modern scholars have debated over the

precise meaning of the passage, and whether Confucius referred to all

women or just certain groups of women.

Further analysis suggests, however, that women's place in Confucian society may be more complex. During the Han dynasty period, the influential Confucian text Lessons for Women (Nüjie), was written by Ban Zhao

(45–114 CE) to instruct her daughters how to be proper Confucian wives

and mothers, that is, to be silent, hard-working, and compliant. She

stresses the complementarity and equal importance of the male and female

roles according to yin-yang theory, but she clearly accepts the

dominance of the male. However, she does present education and literary

power as important for women. In later dynasties, a number of women took

advantage of the Confucian acknowledgment of education to become

independent in thought.

Indeed, as Joseph A. Adler points out, "Neo-Confucian writings do

not necessarily reflect either the prevailing social practices or the

scholars' own attitudes and practices in regard to actual women."

Matthew Sommers has also indicated that the Qing dynasty government

began to realise the utopian nature of enforcing the "cult of chastity"

and began to allow practices such as widow remarrying to stand. Moreover, some Confucian texts like the Chunqiu Fanlu 春秋繁露 have passages that suggest a more equal relationship between a husband and his wife. More recently, some scholars have also begun to discuss the viability of constructing a "Confucian feminism."

Catholic controversy over Chinese rites

Ever since Europeans first encountered Confucianism, the issue of how

Confucianism should be classified has been subject to debate. In the

16th and the 17th centuries, the earliest European arrivals in China,

the Christian Jesuits, considered Confucianism to be an ethical system, not a religion, and one that was compatible with Christianity. The Jesuits, including Matteo Ricci, saw Chinese rituals as "civil rituals" that could co-exist alongside the spiritual rituals of Catholicism.

By the early 18th century, this initial portrayal was rejected by the Dominicans and Franciscans, creating a dispute among Catholics in East Asia that was known as the "Rites Controversy." The Dominicans and Franciscans argued that Chinese ancestral worship was a form of idolatry that was contradictory to the tenets of Christianity. This view was reinforced by Pope Benedict XIV, who ordered a ban on Chinese rituals.

Some critics view Confucianism as definitely pantheistic and nontheistic, in that it is not based on the belief in the supernatural or in a personal god existing separate from the temporal plane.

Confucius views about Tiān 天 and about the divine providence ruling the

world, can be found above (in this page) and in Analects 6:26, 7:22,

and 9:12, for example. On spirituality, Confucius said to Chi Lu, one of

his students: "You are not yet able to serve men, how can you serve

spirits?" Attributes such as ancestor worship, ritual, and sacrifice were advocated by Confucius as necessary for social harmony; these attributes may be traced to the traditional Chinese folk religion.

Scholars recognise that classification ultimately depends on how

one defines religion. Using stricter definitions of religion,

Confucianism has been described as a moral science or philosophy.

But using a broader definition, such as Frederick Streng's

characterisation of religion as "a means of ultimate transformation," Confucianism could be described as a "sociopolitical doctrine having religious qualities."

With the latter definition, Confucianism is religious, even if

non-theistic, in the sense that it "performs some of the basic

psycho-social functions of full-fledged religions."