| Hominoids or Apes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Parvorder: | Catarrhini |

| Superfamily: | Hominoidea Gray, 1825 |

| Type species | |

| Homo sapiens | |

| Families | |

|

†Chororapithecidae †Proconsulidae †Afropithecidae †Pliobatidae Hylobatidae Hominidae sister: Cercopithecoidea | |

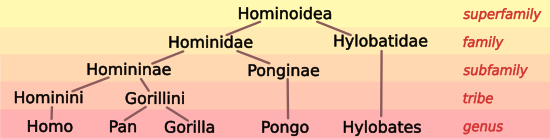

Apes (Hominoidea) are a branch of Old World tailless simians native to Africa and Southeast Asia. They are the sister group of the Old World monkeys, together forming the catarrhine clade. They are distinguished from other primates by a wider degree of freedom of motion at the shoulder joint as evolved by the influence of brachiation. In traditional and non-scientific use, the term "ape" excludes humans, and is thus not equivalent to the scientific taxon Hominoidea. There are two extant branches of the superfamily Hominoidea: the gibbons, or lesser apes; and the hominids, or great apes.

- The family Hylobatidae, the lesser apes, include four genera and a total of sixteen species of gibbon, including the lar gibbon and the siamang, all native to Asia. They are highly arboreal and bipedal on the ground. They have lighter bodies and smaller social groups than great apes.

- The family Hominidae (hominids), the great apes, includes three extant species of orangutans and their subspecies, two extant species of gorillas and their subspecies, two extant species of chimpanzees and their subspecies, and one extant species of humans in a single extant subspecies.

Most non-human hominoids are rare or endangered. The chief threat to most of the endangered species is loss of tropical rainforest habitat, though some populations are further imperiled by hunting for bushmeat. The great apes of Africa are also facing threat from the Ebola virus. Currently considered to be the greatest threat to survival of African apes, Ebola is responsible for the death of at least one third of gorillas and chimpanzees since 1990.

Historical and modern terminology

"Ape", from Old English apa, is a word of uncertain origin. The term has a history of rather imprecise usage—and of comedic or punning usage in the vernacular. Its earliest meaning was generally of any non-human anthropoid primate, as is still the case for its cognates in other Germanic languages. Later, after the term "monkey" had been introduced into English, "ape" was specialized to refer to a tailless (therefore exceptionally human-like) primate. Thus, the term "ape" obtained two different meanings, as shown in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica entry: it could be used as a synonym for "monkey" and it could denote the tailless human-like primate in particular.Some, or recently all, hominoids are also called "apes", but the term is used broadly and has several different senses within both popular and scientific settings. "Ape" has been used as a synonym for "monkey" or for naming any primate with a human-like appearance, particularly those without a tail. Biologists have traditionally used the term "ape" to mean a member of the superfamily Hominoidea other than humans, but more recently to mean all members of Hominoidea. So "ape"—not to be confused with "great ape"—now becomes another word for hominoid including humans.

The term hominoid is not to be confused with hominids, the family of great apes; or with the hominins, the tribe of humans also known as the human clade; or with other very similar terms of primate taxa.

The distinction between apes and monkeys is complicated by the traditional paraphyly of monkeys: Apes emerged as a sister group of Old World Monkeys in the catarhines, which are a sister group of New World Monkeys. Therefore, cladistically, apes, catarrhines and related contemporary extinct groups such as Parapithecidaea are monkeys as well, for any consistent definition of "monkey". "Old World Monkey" may also legitimately be taken to be meant to include all the catarrhines, including apes and extinct species such as Aegyptopithecus, in which case the apes, Cercopithecoidea and Aegyptopithecus emerged within the Old World Monkeys.

The primates called "apes" today became known to Europeans after the 18th century. As zoological knowledge developed, it became clear that taillessness occurred in a number of different and otherwise distantly related species. Sir Wilfrid Le Gros Clark was one of those primatologists who developed the idea that there were trends in primate evolution and that the extant members of the order could be arranged in an ".. ascending series", leading from "monkeys" to "apes" to humans. Within this tradition "ape" came to refer to all members of the superfamily Hominoidea except humans. As such, this use of "apes" represented a paraphyletic grouping, meaning that, even though all species of apes were descended from a common ancestor, this grouping did not include all the descendant species, because humans were excluded from being among the apes.

Traditionally, humans were considered neither apes nor great apes, but today they are recognized as having emerged deep in the phylogenetic tree of apes.

Thus, there are at least three common, or traditional, uses of the term "ape": non-specialists may not distinguish between "monkeys" and "apes", that is, they may use the two terms interchangeably; or they may use "ape" for any tailless monkey or non-human hominoid; or they may use the term "ape" to just mean the non-human hominoids.

Modern biologists and primatologists use monophyletic groups for taxonomic classification; that is, they use only those groups that include all descendants of a common ancestor. The superfamily Hominoidea is such a group—also known as a clade. Some scientists now use the term "ape" to mean all members of the superfamily Hominoidea, including humans. For example, in his 2005 book, Benton wrote "The apes, Hominoidea, today include the gibbons and orang-utan ... the gorilla and chimpanzee ... and humans". Modern biologists and primatologists refer to apes that are not human as "non-human" apes. Scientists broadly, other than paleoanthropologists, may use the term "hominin" to identify the human clade, replacing the term "hominid".

Biology

Like those of the orangutan, the shoulder joints of hominoids are adapted to brachiation, or movement by swinging in tree branches.

The lesser apes are the gibbon family, Hylobatidae, of sixteen

species; all are native to Asia. Their major differentiating

characteristic is their long arms, which they use to brachiate through trees. Their wrists are ball and socket joints as an evolutionary adaptation to their arboreal lifestyle. Generally smaller than the African apes, the largest gibbon, the siamang, weighs up to 14 kg (31 lb); in comparison, the smallest "great ape", the bonobo, is 34 to 60 kg (75 to 132 lb).

Formerly, all the great apes except humans were classified as the family Pongidae, which conveniently provided for separating the human family from the apes; see The "great apes" in Pongidae. As noted above, such a definition would make a paraphyletic

grouping of the Pongidae great apes. Current evidence indicates that

humans share a common ancestor with the chimpanzee line—from which they

separated more recently than from the gorilla line. The superfamily Hominoidea falls within the parvorder Catarrhini,

which also includes the Old World monkeys of Africa and Eurasia. Within

this grouping, the two families Hylobatidae and Hominidae can be

distinguished from Old World monkeys by the number of cusps on their molars; hominoids have five in the "Y-5" molar pattern, whereas Old World monkeys have only four in a bilophodont pattern.

Further, in comparison with Old World monkeys, hominoids are

noted for: more mobile shoulder joints and arms due to the dorsal

position of the scapula;

broader ribcages that are flatter front-to-back; and a shorter, less

mobile spine, with greatly reduced caudal (tail) vertebrae—resulting in

complete loss of the tail in living hominoid species. These are

anatomical adaptations, first, to vertical hanging and swinging

locomotion (brachiation) and, later, to developing balance in a bipedal pose. Note there are primates in other families that also lack tails, and at least one, the pig-tailed langur,

is known to walk significant distances bipedally. The front of the ape

skull is characterised by its sinuses, fusion of the frontal bone, and

by post-orbital constriction.

Although the hominoid fossil record is still incomplete and

fragmentary, there is now enough evidence to provide an outline of the evolutionary history of humans.

Previously, the divergence between humans and other living hominoids

was thought to have occurred 15 to 20 million years ago, and several

species of that time period, such as Ramapithecus, were once thought to be hominins and possible ancestors of humans. But, later fossil finds indicated that Ramapithecus

was more closely related to the orangutan; and new biochemical evidence

indicates that the last common ancestor of humans and non-hominins

(that is, the chimpanzees) occurred between 5 and 10 million years ago,

and probably nearer the lower end of that range; see Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor (CHLCA).

Diet

Apart from humans and gorillas, apes eat a predominantly frugivorous diet, mostly fruit, but supplemented with a variety of other foods. Gorillas are predominately folivorous,

eating mostly stalks, shoots, roots and leaves with some fruit and

other foods. Non-human apes usually eat a small amount of raw animal

foods such as insects or eggs. In the case of humans, migration and the

invention of hunting tools and cooking has led to an even wider variety

of foods and diets, with many human diets including large amounts of

cooked tubers (roots) or legumes.

Other food production and processing methods including animal husbandry

and industrial refining and processing have further changed human

diets. Humans and other apes occasionally eat other primates. Some of these primates are now close to extinction with habitat loss being the underlying cause.

Behaviour and cognition

A series of images showing a gorilla utilizing a small tree trunk as a tool to maintain balance as she fished for aquatic herbs

Although there had been earlier studies, the scientific investigation

of behaviour and cognition in non-human members of the superfamily

Hominoidea expanded enormously during the latter half of the twentieth

century. Major studies of behaviour in the field were completed on the

three better-known "great apes", for example by Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Birute Galdikas.

These studies have shown that in their natural environments, the

non-human hominoids show sharply varying social structure: gibbons are

monogamous, territorial pair-bonders, orangutans are solitary, gorillas

live in small troops with a single adult male leader, while chimpanzees

live in larger troops with bonobos exhibiting promiscuous sexual

behaviour. Their diets also vary; gorillas are foliovores, while the others are all primarily frugivores, although the common chimpanzee does some hunting for meat. Foraging behaviour is correspondingly variable.

All the non-human hominoids are generally thought of as highly

intelligent, and scientific study has broadly confirmed that they

perform very well on a wide range of cognitive tests—though there is

relatively little data on gibbon cognition. The early studies by Wolfgang Köhler demonstrated exceptional problem-solving abilities in chimpanzees, which Köhler attributed to insight. The use of tools

has been repeatedly demonstrated; more recently, the manufacture of

tools has been documented, both in the wild and in laboratory tests. Imitation is much more easily demonstrated in "great apes" than in other primate species. Almost all the studies in animal language acquisition

have been done with "great apes", and though there is continuing

dispute as to whether they demonstrate real language abilities, there is

no doubt that they involve significant feats of learning. Chimpanzees

in different parts of Africa have developed tools that are used in food

acquisition, demonstrating a form of animal culture.

Distinction from monkeys

Cladistically, apes, catarrhines, and extinct species such as Aegyptopithecus and Parapithecidaea, are monkeys, so one can only specify ape features not present in other monkeys.

Apes do not possess a tail, unlike most monkeys.

Monkeys are more likely to be in trees and use their tails for balance.

While the great apes are considerably larger than monkeys, gibbons

(lesser apes) are smaller than some monkeys. Apes are considered to be

more intelligent than monkeys, which are considered to have more

primitive brains.

History of hominoid taxonomy

The history of hominoid taxonomy is complex and somewhat confusing.

Recent evidence has changed our understanding of the relationships

between the hominoids, especially regarding the human lineage; and the

traditionally used terms have become somewhat confused. Competing

approaches to methodology and terminology are found among current

scientific sources. Over time, authorities have changed the names and

the meanings of names of groups and subgroups as new evidence—that is,

new discoveries of fossils and tools and of observations in the field,

plus continual comparisons of anatomy and DNA sequences—has changed the

understanding of relationships between hominoids. There has been a

gradual demotion of humans from being 'special' in the taxonomy to being

one branch among many. This recent turmoil (of history) illustrates the

growing influence on all taxonomy of cladistics, the science of classifying living things strictly according to their lines of descent.

Today, there are eight extant genera of hominoids. They are the four genera in the family Hominidae, namely Homo, Pan, Gorilla, and Pongo; plus four genera in the family Hylobatidae (gibbons): Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus and Symphalangus. (The two subspecies of hoolock gibbons were recently moved from the genus Bunopithecus to the new genus Hoolock and re-ranked as species; a third species was described in January 2017).)

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus, relying on second- or third-hand accounts, placed a second species in Homo along with H. sapiens: Homo troglodytes

("cave-dwelling man"). Although the term "Orang Outang" is listed as a

variety - Homo sylvestris - under this species, it is nevertheless not

clear to which animal this name refers, as Linnaeus had no specimen to

refer to, hence no precise description. Linnaeus may have based Homo Troglodytes on reports of mythical creatures, then-unidentified simians, or Asian natives dressed in animal skins. Linnaeus named the orangutan Simia satyrus ("satyr monkey"). He placed the three genera Homo, Simia and Lemur in the order of Primates.

The troglodytes name was used for the chimpanzee by Blumenbach in 1775, but moved to the genus Simia. The orangutan was moved to the genus Pongo in 1799 by Lacépède.

Linnaeus's inclusion of humans in the primates with monkeys and

apes was troubling for people who denied a close relationship between

humans and the rest of the animal kingdom. Linnaeus's Lutheran

archbishop had accused him of "impiety". In a letter to Johann Georg Gmelin dated 25 February 1747, Linnaeus wrote:

It is not pleasing to me that I must place humans among the primates, but man is intimately familiar with himself. Let's not quibble over words. It will be the same to me whatever name is applied. But I desperately seek from you and from the whole world a general difference between men and simians from the principles of Natural History. I certainly know of none. If only someone might tell me one! If I called man a simian or vice versa I would bring together all the theologians against me. Perhaps I ought to, in accordance with the law of Natural History.

Accordingly, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in the first edition of his Manual of Natural History (1779), proposed that the primates be divided into the Quadrumana (four-handed, i.e. apes and monkeys) and Bimana (two-handed, i.e. humans). This distinction was taken up by other naturalists, most notably Georges Cuvier. Some elevated the distinction to the level of order.

However, the many affinities between humans and other primates — and

especially the "great apes" — made it clear that the distinction made no

scientific sense. In The Descent of Man, Charles Darwin wrote:

The greater number of naturalists who have taken into consideration the whole structure of man, including his mental faculties, have followed Blumenbach and Cuvier, and have placed man in a separate Order, under the title of the Bimana, and therefore on an equality with the orders of the Quadrumana, Carnivora, etc. Recently many of our best naturalists have recurred to the view first propounded by Linnaeus, so remarkable for his sagacity, and have placed man in the same Order with the Quadrumana, under the title of the Primates. The justice of this conclusion will be admitted: for in the first place, we must bear in mind the comparative insignificance for classification of the great development of the brain in man, and that the strongly marked differences between the skulls of man and the Quadrumana (lately insisted upon by Bischoff, Aeby, and others) apparently follow from their differently developed brains. In the second place, we must remember that nearly all the other and more important differences between man and the Quadrumana are manifestly adaptive in their nature, and relate chiefly to the erect position of man; such as the structure of his hand, foot, and pelvis, the curvature of his spine, and the position of his head.

Changes in taxonomy and terminology ("hominid" v "hominin")

| Humans the non-apes: Until about 1960, taxonomists typically divided the superfamily Hominoidea into two families. The science community treated humans and their extinct relatives as the outgroup within the superfamily; that is, humans were considered as quite distant from kinship with the "apes". Humans were classified as the family Hominidae and were known as the "hominids". All other hominoids were known as "apes" and were referred to the family Pongidae. | |

| The "great apes" in Pongidae: The 1960s saw the methodologies of molecular biology applied to primate taxonomy. Goodman's 1964 immunological study of serum proteins led to re-classifying the hominoids into three families: the humans in Hominidae; the great apes in Pongidae; and the "lesser apes" (gibbons) in Hylobatidae. However, a trichotomy—Pan, Gorilla, and Pongo—of the "great apes" in Pongidae presented a puzzle; scientists wanted to know which genus speciated first from the common hominoid ancestor. | |

| Gibbons the outgroup: New studies indicated that gibbons, not humans, are the outgroup within the superfamily Hominoidea, meaning: the rest of the hominoids are more closely related to each other than (any of them) are to the gibbons. With this splitting, the gibbons (Hylobates, et al.) were isolated after moving the great apes into the same family as humans. Now the term "hominid" encompassed a larger collective taxa within the family Hominidae. The trichotomy still required scientists to learn which genus is 'least' related to the others. | |

| Orangutans the outgroup: Investigations comparing humans and the three other hominid genera disclosed that the African apes (chimpanzees and gorillas) and humans are more closely related to each other than any of them are to the Asian orangutans (Pongo); that is, the orangutans, not humans, are the outgroup within the family Hominidae. This led to reassigning the African apes to the subfamily Homininae with humans—which presented a new three-way split (trichotomy), Homo, Pan, Gorilla. | |

| Hominins: In an effort to resolve the trichotomy, while preserving the "outgroup" status of humans, the subfamily Homininae was divided into two tribes: Gorillini, comprising genus Pan and genus Gorilla; and Hominini, comprising genus Homo (the humans). Humans and close relatives now began to be known as "hominins", that is, of the tribe Hominini. Thus, the term "hominin" succeeded to the previous use of "hominid", which meaning had changed with changes in Hominidae (see above: 3rd graphic, "Gibbons the outgroup"). | |

| Gorillas the outgroup: New DNA comparisons now provided evidence that gorillas, not humans, are the outgroup in the subfamily Homininae; this suggested that chimpanzees should be grouped with humans in the tribe Hominini, but in separate subtribes. Now the name "hominin" delineated Homo plus those earliest Homo relatives and ancestors that arose after the divergence from the chimpanzees. (Humans are no longer an outgroup, but are a branch, deep in the tree of the pre-1960s ape group.) | |

| Speciation of gibbons: Later DNA comparisons disclosed previously unknown speciation of genus Hylobates (gibbons) into four genera: Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus, and Symphalangus. |

Classification and evolution

Skeletons of members of the ape superfamily, Hominoidea. There are two extant families: Hominidae, the "great apes"; and Hylobatidae, the gibbons, or "lesser apes".

As discussed above, hominoid taxonomy has undergone several changes.

Genetic analysis combined with fossil evidence indicates that hominoids

diverged from the Old World monkeys about 25 million years ago (mya), near the Oligocene-Miocene boundary. The gibbons split from the rest about 18 mya, and the hominid splits happened 14 mya (Pongo), 7 mya (Gorilla), and 3–5 mya (Homo & Pan). In 2015, a new genus and species were described, Pliobates cataloniae, which lived 11.6 mya, and appears to predate the split between Hominidae and Hylobatidae.

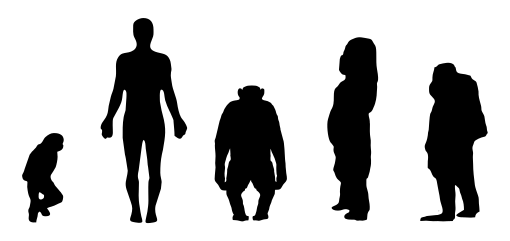

From

left: Comparison of size of gibbon, human, chimpanzee, gorilla and

orangutan. Non-human apes do not normally stand upright as their normal

posture.

The families, and extant genera and species of hominoids are:

- Superfamily Hominoidea

- Family Hominidae: hominids ("great apes")

- Genus Pongo: orangutans

- Bornean orangutan, P. pygmaeus

- Sumatran orangutan, P. abelii

- Tapanuli orangutan, P. tapanuliensis

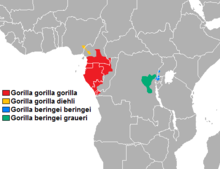

- Genus Gorilla: gorillas

- Western gorilla, G. gorilla

- Eastern gorilla, G. beringei

- Genus Homo: humans

- Human, H. sapiens

- Genus Pan: chimpanzees

- Common chimpanzee, P. troglodytes

- Bonobo, P. paniscus

- Genus Pongo: orangutans

- Family Hylobatidae: gibbons ("lesser apes")

- Genus Hylobates

- Lar gibbon or white-handed gibbon, H. lar

- Bornean white-bearded gibbon, H. albibarbis

- Agile gibbon or black-handed gibbon, H. agilis

- Müller's Bornean gibbon or grey gibbon, H. muelleri

- Silvery gibbon, H. moloch

- Pileated gibbon or capped gibbon, H. pileatus

- Kloss's gibbon or Mentawai gibbon or bilou, H. klossii

- Genus Hoolock

- Western hoolock gibbon, H. hoolock

- Eastern hoolock gibbon, H. leuconedys

- Skywalker hoolock gibbon, H. tianxing

- Genus Symphalangus

- Siamang, S. syndactylus

- Genus Nomascus

- Northern buffed-cheeked gibbon, N. annamensis

- Black crested gibbon, N. concolor

- Eastern black crested gibbon, N. nasutus

- Hainan black crested gibbon, N. hainanus

- Southern white-cheeked gibbon N. siki

- White-cheeked crested gibbon, N. leucogenys

- Yellow-cheeked gibbon, N. gabriellae

- Genus Hylobates

- Family Hominidae: hominids ("great apes")