Solitary predator: A polar bear feeds on a bearded seal it has killed.

Social predators: Meat ants cooperate to feed on a cicada far larger than themselves.

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the host) and parasitoidism (which always does, eventually). It is distinct from scavenging on dead prey, though many predators also scavenge; it overlaps with herbivory, as a seed predator is both a predator and a herbivore.

Predators may actively search for prey or sit and wait for it.

When prey is detected, the predator assesses whether to attack it. This

may involve ambush or pursuit predation,

sometimes after stalking the prey. If the attack is successful, the

predator kills the prey, removes any inedible parts like the shell or

spines, and eats it.

Predators are adapted and often highly specialized for hunting, with acute senses such as vision, hearing, or smell. Many predatory animals, both vertebrate and invertebrate, have sharp claws or jaws to grip, kill, and cut up their prey. Other adaptations include stealth and aggressive mimicry that improve hunting efficiency.

Predation has a powerful selective effect on prey, and the prey develop antipredator adaptations such as warning coloration, alarm calls and other signals, camouflage, mimicry of well-defended species, and defensive spines and chemicals. Sometimes predator and prey find themselves in an evolutionary arms race, a cycle of adaptations and counter-adaptations. Predation has been a major driver of evolution since at least the Cambrian period.

Definition

Spider wasps paralyse and eventually kill their hosts, but are considered parasitoids, not predators.

At the most basic level, predators kill and eat other organisms.

However, the concept of predation is broad, defined differently in

different contexts, and includes a wide variety of feeding methods; and

some relationships that result in the prey's death are not generally

called predation. A parasitoid, such as an ichneumon wasp,

lays its eggs in or on its host; the eggs hatch into larvae, which eat

the host, and it inevitably dies. Zoologists generally call this a form

of parasitism,

though conventionally parasites are thought not to kill their hosts. A

predator can be defined to differ from a parasitoid in two ways: it

kills its prey immediately; and it has many prey, captured over its

lifetime, where a parasitoid's larva has just one, or at least has its

food supply provisioned for it on just one occasion.

Relation of predation to other feeding strategies

There are other difficult and borderline cases. Micropredators are small animals that, like predators, feed entirely on other organisms; they include fleas and mosquitoes that consume blood from living animals, and aphids

that consume sap from living plants. However, since they typically do

not kill their hosts, they are now often thought of as parasites. Animals that graze on phytoplankton

or mats of microbes are predators, as they consume and kill their food

organisms; but herbivores that browse leaves are not, as their food

plants usually survive the assault. However, when animals eat seeds (seed predation or granivory) or eggs (egg predation), they are consuming entire living organisms, which by definition makes them predators,

albeit unconventional ones: for instance, a mouse that eats grass seeds

has no adaptations for tracking, catching and subduing prey and its

teeth are not adapted to slicing through flesh.

Scavengers, organisms that only eat organisms found already dead, are not predators, but many predators such as the jackal and the hyena scavenge when the opportunity arises. Among invertebrates, social wasps (yellowjackets) are both hunters and scavengers of other insects.

Taxonomic range

While examples of predators among mammals and birds are well known, predators can be found in a broad range of taxa. They are common among insects, including mantids, dragonflies, lacewings and scorpionflies. In some species such as the alderfly,

only the larvae are predatory (the adults do not eat). Spiders are

predatory, as well as other terrestrial invertebrates such as scorpions; centipedes; some mites, snails and slugs; nematodes; and planarian worms. In marine environments, most cnidarians (e.g., jellyfish, hydroids), ctenophora (comb jellies), echinoderms (e.g., sea stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers) and flatworms are predatory. Among crustaceans, lobsters, crabs, shrimps and barnacles are predators, and in turn crustaceans are preyed on by nearly all cephalopods (including octopuses, squid and cuttlefish).

Paramecium, a predatory ciliate, feeding on bacteria

Seed predation is restricted to mammals, birds, and insects and is found in almost all terrestrial ecosystems. Egg predation includes both specialist egg predators such as some colubrid snakes and generalists such as foxes and badgers that opportunistically take eggs when they find them.

Some plants, like the pitcher plant, the Venus fly trap and the sundew, are carnivorous and consume insects. Some carnivorous fungi catch nematodes using either active traps in the form of constricting rings, or passive traps with adhesive structures.

Many species of protozoa (eukaryotes) and bacteria (prokaryotes) prey on other microorganisms; the feeding mode is evidently ancient, and evolved many times in both groups. Among freshwater and marine zooplankton, whether single-celled or multi-cellular, predatory grazing on phytoplankton and smaller zooplankton is common, and found in many species of nanoflagellates, dinoflagellates, ciliates, rotifers, a diverse range of meroplankton animal larvae, and two groups of crustaceans, namely copepods and cladocerans.

Foraging

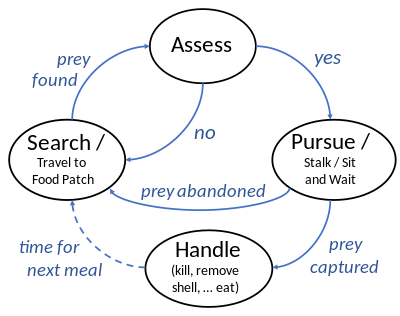

A basic foraging cycle for a predator, with some variations indicated

To feed, a predator must search for, pursue and kill its prey. These actions form a foraging cycle.

The predator must decide where to look for prey based on its

geographical distribution; and once it has located prey, it must assess

whether to pursue it or to wait for a better choice. If it chooses

pursuit, its physical capabilities determine the mode of pursuit (e.g.,

ambush or chase). Having captured the prey, it may also need to expend energy handling it (e.g., killing it, removing any shell or spines, and ingesting it).

Search

Predators have a choice of search modes ranging from sit-and-wait to active or widely foraging. The sit-and-wait method is most suitable if the prey are dense and mobile, and the predator has low energy requirements. Wide foraging expends more energy, and is used when prey is sedentary or sparsely distributed. There is a continuum of search modes with intervals between periods of movement ranging from seconds to months. Sharks, sunfish, Insectivorous birds and shrews are almost always moving while web-building spiders, aquatic invertebrates, praying mantises and kestrels rarely move. In between, plovers and other shorebirds, freshwater fish including crappies, and the larvae of coccinellid beetles (ladybirds), alternate between actively searching and scanning the environment.

The black-browed albatross regularly flies hundreds of kilometres across the nearly empty ocean to find patches of food.

Prey distributions are often clumped, and predators respond by looking for patches where prey is dense and then searching within patches.

Where food is found in patches, such as rare shoals of fish in a nearly

empty ocean, the search stage requires the predator to travel for a

substantial time, and to expend a significant amount of energy, to

locate each food patch. For example, the black-browed albatross

regularly makes foraging flights to a range of around 700 kilometres

(430 miles), up to a maximum foraging range of 3,000 kilometres (1,860

miles) for breeding birds gathering food for their young. With static prey, some predators can learn suitable patch locations and return to them at intervals to feed. The optimal foraging strategy for search has been modelled using the marginal value theorem.

Search patterns often appear random. One such is the Lévy walk, that tends to involve clusters of short steps with occasional long steps. It is a good fit to the behaviour of a wide variety of organisms including bacteria, honeybees, sharks and human hunter-gatherers.

Assessment

Seven-spot ladybirds select plants of good quality for their aphid prey.

Having found prey, a predator must decide whether to pursue it or

keep searching. The decision depends on the costs and benefits involved.

A bird foraging for insects spends a lot of time searching but

capturing and eating them is quick and easy, so the efficient strategy

for the bird is to eat every palatable insect it finds. By contrast, a

predator such as a lion or falcon finds its prey easily but capturing it

requires a lot of effort. In that case, the predator is more selective.

One of the factors to consider is size. Prey that is too small

may not be worth the trouble for the amount of energy it provides. Too

large, and it may be too difficult to capture. For example, a mantid

captures prey with its forelegs and they are optimized for grabbing prey

of a certain size. Mantids are reluctant to attack prey that is far

from that size. There is a positive correlation between the size of a

predator and its prey.

A predator may also assess a patch and decide whether to spend time searching for prey in it. This may involve some knowledge of the preferences of the prey; for example, ladybirds can choose a patch of vegetation suitable for their aphid prey.

Capture

To capture prey, predators have a spectrum of pursuit modes that range from overt chase (also known as pursuit predation) to a sudden strike on nearby prey (ambush predation). Another strategy in between ambush and pursuit is ballistic interception, where a predator observes and predicts a prey's motion and then launches its attack accordingly.

Ambush

Ambush or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals that capture

prey by stealth or surprise. In animals, ambush predation is

characterized by the predator's scanning the environment from a

concealed position until a prey is spotted, and then rapidly executing a

fixed surprise attack. Vertebrate ambush predators include frogs, fish such as the angel shark, the northern pike and the eastern frogfish. Among the many invertebrate ambush predators are trapdoor spiders on land and mantis shrimps in the sea.

Ambush predators often construct a burrow in which to hide, improving

concealment at the cost of reducing their field of vision. Some ambush

predators also use lures to attract prey within striking range. The capturing movement has to be rapid to trap the prey, given that the attack is not modifiable once launched.

Ballistic interception

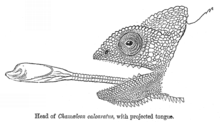

The chameleon attacks prey by shooting out its tongue.

Ballistic interception is the strategy where a predator observes the

movement of a prey, predicts its motion, works out an interception path,

and then attacks the prey on that path. This differs from ambush

predation in that the predator adjusts its attack according to how the

prey is moving.

Ballistic interception involves a brief period for planning, giving

the prey an opportunity to escape. Some frogs wait until snakes have

begun their strike before jumping, reducing the time available to the

snake to recalibrate its attack, and maximising the angular adjustment

that the snake would need to make to intercept the frog in real time. Ballistic predators include insects such as dragonflies, and vertebrates such as archerfish (attacking with a jet of water), chameleons (attacking with their tongues), and some colubrid snakes.

Pursuit

Humpback whales are lunge feeders, filtering thousands of krill from seawater and swallowing them alive.

In pursuit predation, predators chase fleeing prey. If the prey flees

in a straight line, capture depends only on the predator's being faster

than the prey.

If the prey manoeuvres by turning as it flees, the predator must react

in real time to calculate and follow a new intercept path, such as by parallel navigation, as it closes on the prey. Many pursuit predators use camouflage to approach the prey as close as possible unobserved (stalking) before starting the pursuit.

Pursuit predators include terrestrial mammals such as lions, cheetahs,

and wolves; marine predators such as dolphins and many predatory fishes,

such as tuna; predatory birds (raptors) such as falcons; and insects such as dragonflies.

An extreme form of pursuit is endurance or persistence hunting,

in which the predator tires out the prey by following it over a long

distance, sometimes for hours at a time. The method is used by human hunter-gatherers and in canids such as African wild dogs

and domestic hounds. The African wild dog is an extreme persistence

predator, tiring out individual prey by following them for many miles at

relatively low speed, compared for example to the cheetah's brief high-speed pursuit.

A specialised form of pursuit predation is the lunge feeding of baleen whales. These very large marine predators feed on plankton, especially krill,

diving and actively swimming into concentrations of plankton, and then

taking a huge gulp of water and filtering it through their feathery baleen plates.

Pursuit predators may be social, like the lion and wolf that hunt in groups, or solitary, like the cheetah.

Handling

Catfish has sharp dorsal and pectoral spines which it holds erect to discourage predators such as herons which swallow prey whole.

Once the predator has captured the prey, it has to handle it: very

carefully if the prey is dangerous to eat, such as if it possesses sharp

or poisonous spines, as in many prey fish. Some catfish such as the Ictaluridae have spines on the back (dorsal) and belly (pectoral)

which lock in the erect position; as the catfish thrashes about when

captured, these could pierce the predator's mouth, possibly fatally.

Some fish-eating birds like the osprey avoid the danger of spines by tearing up their prey before eating it.

Solitary versus social predation

In social predation, a group of predators cooperates to kill prey.

This makes it possible to kill creatures larger than those they could

overpower singly; for example, hyenas, and wolves collaborate to catch and kill herbivores as large as buffalo, and lions even hunt elephants.

It can also make prey more readily available through strategies like

flushing of prey and herding it into a smaller area. For example, when

mixed flocks of birds forage, the birds in front flush out insects that

are caught by the birds behind. Spinner dolphins form a circle around a school of fish and move inwards, concentrating the fish by a factor of 200. By hunting socially chimpanzees can catch colobus monkeys that would readily escape an individual hunter, while cooperating Harris hawks can trap rabbits.

Wolves, social predators, cooperate to hunt and kill bison.

Predators of different species sometimes cooperate to catch prey. In coral reefs, when fish such as the grouper and coral trout spot prey that is inaccessible to them, they signal to giant moray eels, Napoleon wrasses or octopuses. These predators are able to access small crevices and flush out the prey. Killer whales have been known to help whalers hunt baleen whales.

Social hunting allows predators to tackle a wider range of prey,

but at the risk of competition for the captured food. Solitary predators

have more chance of eating what they catch, at the price of increased

expenditure of energy to catch it, and increased risk that the prey will

escape. Ambush predators are often solitary to reduce the risk of becoming prey themselves. Of 245 terrestrial carnivores, 177 are solitary; and 35 of the 37 wild cats are solitary, including the cougar and cheetah. However, the solitary cougar does allow other cougars to share in a kill, and the coyote can be either solitary or social. Other solitary predators include the northern pike, wolf spiders and all the thousands of species of solitary wasps among arthropods, and many microorganisms and zooplankton.

Specialization

Physical adaptations

Under the pressure of natural selection, predators have evolved a variety of physical adaptations

for detecting, catching, killing, and digesting prey. These include

speed, agility, stealth, sharp senses, claws, teeth, filters, and

suitable digestive systems.

For detecting prey, predators have well-developed vision, smell, or hearing. Predators as diverse as owls and jumping spiders have forward-facing eyes, providing accurate binocular vision

over a relatively narrow field of view, whereas prey animals often have

less acute all-round vision. Animals such as foxes can smell their prey

even when it is concealed under 2 feet (60 cm) of snow or earth. Many

predators have acute hearing, and some such as echolocating bats hunt exclusively by active or passive use of sound.

Predators including big cats, birds of prey, and ants share powerful jaws, sharp teeth, or claws which they use to seize and kill their prey. Some predators such as snakes and fish-eating birds like herons and cormorants

swallow their prey whole; some snakes can unhinge their jaws to allow

them to swallow large prey, while fish-eating birds have long spear-like

beaks that they use to stab and grip fast-moving and slippery prey. Fish and other predators have developed the ability to crush or open the armoured shells of molluscs.

Many predators are powerfully built and can catch and kill

animals larger than themselves; this applies as much to small predators

such as ants and shrews as to big and visibly muscular carnivores like the cougar and lion.

- Skull of brown bear has large pointed canines for killing prey, and self-sharpening carnassial teeth at rear for cutting flesh with a scissor-like action

- Crab spider, an ambush predator with forward-facing eyes, catching another predator, a field digger wasp

Diet and behaviour

Size-selective predation: a lioness attacking a Cape buffalo, roughly twice her weight. Lions can attack much larger prey, including elephants, but do so much less often.

Predators are often highly specialized in their diet and hunting behaviour; for example, the Eurasian lynx only hunts small ungulates. Others such as leopards are more opportunistic generalists, preying on at least 100 species.

The specialists may be highly adapted to capturing their preferred

prey, whereas generalists may be better able to switch to other prey

when a preferred target is scarce. When prey have a clumped (uneven)

distribution, the optimal strategy for the predator is predicted to be

more specialized as the prey are more conspicuous and can be found more

quickly; this appears to be correct for predators of immobile prey, but is doubtful with mobile prey.

In size-selective predation, predators select prey of a certain size.

Large prey may prove troublesome for a predator, while small prey might

prove hard to find and in any case provide less of a reward. This has

led to a correlation between the size of predators and their prey. Size

may also act as a refuge for large prey. For example, adult elephants are relatively safe from predation by lions, but juveniles are vulnerable.

Camouflage and mimicry

Striated frogfish uses camouflage and aggressive mimicry in the form of a fishing rod-like lure on its head to attract prey.

Members of the cat family such as the snow leopard (treeless highlands), tiger (grassy plains, reed swamps), ocelot (forest), fishing cat (waterside thickets), and lion (open plains) are camouflaged with coloration and disruptive patterns suiting their habitats.

In aggressive mimicry, certain predators, including insects and fishes, make use of coloration and behaviour to attract prey. Female Photuris fireflies, for example, copy the light signals of other species, thereby attracting male fireflies, which they capture and eat. Flower mantises are ambush predators; camouflaged as flowers, such as orchids, they attract prey and seize it when it is close enough. Frogfishes are extremely well camouflaged, and actively lure their prey to approach using an esca,

a bait on the end of a rod-like appendage on the head, which they wave

gently to mimic a small animal, gulping the prey in an extremely rapid

movement when it is within range.

Venom

Many smaller predators such as the box jellyfish use venom to subdue their prey, and venom can also aid in digestion (as is the case for rattlesnakes and some spiders). The marbled sea snake that has adapted to egg predation has atrophied venom glands, and the gene for its three finger toxin contains a mutation (the deletion of two nucleotides) that inactives it. These changes are explained by the fact that its prey does not need to be subdued.

Physiology

Physiological adaptations to predation include the ability of predatory bacteria to digest the complex peptidoglycan polymer from the cell walls of the bacteria that they prey upon.

Carnivorous vertebrates of all five major classes (fishes, amphibians,

reptiles, birds, and mammals) have lower relative rates of sugar to amino acid transport than either herbivores or omnivores, presumably because they acquire plenty of amino acids from the animal proteins in their diet.

Antipredator adaptations

To counter predation, prey have a great variety of defences. They can

try to avoid detection. They can detect predators and warn others of

their presence. If detected, they can try to avoid being the target of

an attack, for example, by signalling that a chase would be unprofitable

or by forming groups. If they become a target, they can try to fend off

the attack with defences such as armour, quills, unpalatability or

mobbing; and they can escape an attack in progress by startling the predator, shedding body parts such as tails, or simply fleeing.

Avoiding detection

Prey

can avoid detection by predators with morphological traits and

coloration that make them hard to detect. They can also adopt behaviour

that avoids predators by, for example, avoiding the times and places

where predators forage.

Misdirection

Prey animals make use of a variety of mechanisms including camouflage and mimicry

to misdirect the visual sensory mechanisms of predators, enabling the

prey to remain unrecognized for long enough to give it an opportunity to

escape. Camouflage delays recognition through coloration, shape, and

pattern. Among the many mechanisms of camouflage are countershading and disruptive coloration. The resemblance can be to the biotic or non-living environment, such as a mantis resembling dead leaves, or to other organisms. In mimicry, an organism has a similar appearance to another species, as in the drone fly, which resembles a bee yet has no sting.

Behavioural mechanisms

Black woodpecker attending its chicks, relatively safe inside an excavated hole in a tree

Animals avoid predators with behavioural mechanisms such as changing

their habitats (particularly when raising young), reducing their

activity, foraging less and forgoing reproduction when they sense that

predators are about.

Eggs and nestlings are particularly vulnerable to predation, so birds take measures to protect their nests. Where birds locate their nests can have a large effect on the frequency of predation. It is lowest for those such as woodpeckers that excavate their own nests and progressively higher for those on the ground, in canopies and in shrubs.

To compensate, shrub nesters must have more broods and shorter nesting

times. Birds also choose appropriate habitat (e.g., thick foliage or

islands) and avoid forest edges and small habitats. Similarly, some

mammals raise their young in dens.

By forming groups, prey can often reduce the frequency of

encounters with predators because the visibility of a group does not

rise in proportion to its size. However, there are exceptions: for

example, human fishermen can only detect large shoals of fish with sonar.

Detecting predators

Recognition

Prey species use sight, sound and odor to detect predators, and they can be quite discriminating. For example, Belding's ground squirrel

can distinguish several aerial and ground predators from each other and

from harmless species. Prey also distinguish between the calls of

predators and non-predators. Some species can even distinguish between

dangerous and harmless predators of the same species. In the

northeastern Pacific Ocean, transient killer whales prey on seals, but

the local killer whales only eat fish. Seals rapidly exit the water if

they hear calls between transients. Prey are also more vigilant if they

smell predators.

Eurasian jay is constantly alert for predators, warning of their presence with loud alarm calls.

The abilities of prey to detect predators do have limits. Belding's ground squirrel cannot distinguish between harriers flying at different heights, although only the low-flying birds are a threat.

Wading birds sometimes take flight when there does not appear to be any

predator present. Although such false alarms waste energy and lose

feeding time, it can be fatal to make the opposite mistake of taking a

predator for a harmless animal.

Vigilance

Prey must remain vigilant, scanning their surroundings for

predators. This makes it more difficult to feed and sleep. Groups can

provide more eyes, making detection of a predator more likely and

reducing the level of vigilance needed by individuals. Many species, such as Eurasian jays, give alarm calls

warning of the presence of a predator; these give other prey of the

same or different species an opportunity to escape, and signal to the

predator that it has been detected.

Avoiding an attack

Signalling unprofitability

If predator and prey have spotted each other, the prey can signal to

the predator to decrease the likelihood of an attack. These honest signals may benefit both the prey and predator, because they save the effort of a fruitless chase. Signals that appear to deter attacks include stotting, for example by Thomson's gazelle; push-up displays by lizards; and good singing by skylarks after a pursuit begins.

Simply indicating that the predator has been spotted, as a hare does by

standing on its hind legs and facing the predator, may sometimes be

sufficient.

Many prey animals are aposematically coloured or patterned as a warning to predators that they are distasteful or able to defend themselves. Such distastefulness or toxicity is brought about by chemical defences, found in a wide range of prey, especially insects, but the skunk is a dramatic mammalian example.

Forming groups

By forming groups, prey can reduce attacks by predators. There are several mechanisms that produce this effect. One is dilution,

where, in the simplest scenario, if a given predator attacks a group of

prey, the chances of a given individual being the target is reduced in

proportion to the size of the group. However, it is difficult to

separate this effect from other group-related benefits such as increased

vigilance and reduced encounter rate. Other advantages include confusing predators such as with motion dazzle, making it more difficult to single out a target.

Fending off an attack

When attacked, many moths such as Spirama helicina open their wings to reveal eyespots, in a deimatic or bluffing display.

Chemical defences include toxins, such as bitter compounds in leaves

absorbed by leaf-eating insects, are used to dissuade potential

predators. Mechanical defences include sharp spines, hard shells and tough leathery skin or exoskeletons, all making prey harder to kill.

Some species mob predators cooperatively, reducing the likelihood of attack.

Escaping an attack

When a predator is approaching an individual and attack seems

imminent, the prey still has several options. One is to flee, whether by

running, jumping, climbing, burrowing or swimming. The prey can gain some time by startling the predator. Many butterflies and moths have eyespots, wing markings that resemble eyes. When a predator disturbs the insect, it reveals its hind wings in a in a deimatic or bluffing display, startling the predator and giving the insect time to escape. Some other strategies include playing dead and uttering a distress call.

Coevolution

Bats use echolocation to hunt moths at night.

Predators and prey are natural enemies, and many of their adaptations

seem designed to counter each other. For example, bats have

sophisticated echolocation

systems to detect insects and other prey, and insects have developed a

variety of defences including the ability to hear the echolocation

calls.

Many pursuit predators that run on land, such as wolves, have evolved

long limbs in response to the increased speed of their prey. Their adaptations have been characterized as an evolutionary arms race, an example of the coevolution of two species. In a gene centered view of evolution, the genes of predator and prey can be thought of as competing for the prey's body.

However, the "life-dinner" principle of Dawkins and Krebs predicts that

this arms race is asymmetric: if a predator fails to catch its prey, it

loses its dinner, while if it succeeds, the prey loses its life.

Eastern coral snake,

itself a predator, is venomous enough to kill predators that attack it,

so when they avoid it, this behaviour must be inherited, not learnt.

The metaphor of an arms race implies ever-escalating advances in

attack and defence. However, these adaptations come with a cost; for

instance, longer legs have an increased risk of breaking,

while the specialized tongue of the chameleon, with its ability to act

like a projectile, is useless for lapping water, so the chameleon must

drink dew off vegetation.

The "life-dinner" principle has been criticized on multiple

grounds. The extent of the asymmetry in natural selection depends in

part on the heritability of the adaptive traits. Also, if a predator loses enough dinners, it too will lose its life.

On the other hand, the fitness cost of a given lost dinner is

unpredictable, as the predator may quickly find better prey. In

addition, most predators are generalists, which reduces the impact of a

given prey adaption on a predator. Since specialization is caused by

predator-prey coevolution, the rarity of specialists may imply that

predator-prey arms races are rare.

It is difficult to determine whether given adaptations are truly

the result of coevolution, where a prey adaptation gives rise to a

predator adaptation that is countered by further adaptation in the prey.

An alternative explanation is escalation, where predators are adapting to competitors, their own predators or dangerous prey.

Apparent adaptations to predation may also have arisen for other

reasons and then been co-opted for attack or defence. In some of the

insects preyed on by bats, hearing evolved before bats appeared and was

used to hear signals used for territorial defence and mating.

Their hearing evolved in response to bat predation, but the only clear

example of reciprocal adaptation in bats is stealth echolocation.

A more symmetric arms race may occur when the prey are dangerous,

having spines, quills, toxins or venom that can harm the predator. The

predator can respond with avoidance, which in turn drives the evolution

of mimicry. Avoidance is not necessarily an evolutionary response as it

is generally learned from bad experiences with prey. However, when the

prey is capable of killing the predator (as can a coral snake

with its venom), there is no opportunity for learning and avoidance

must be inherited. Predators can also respond to dangerous prey with

counter-adaptations. In western North America, the common garter snake has developed a resistance to the toxin in the skin of the rough-skinned newt.

Role in ecosystems

Trophic level

Secondary consumer: a mantis (Tenodera aridifolia) eating a bee

One way of classifying predators is by trophic level. Carnivores that feed on herbivores are secondary consumers; their predators are tertiary consumers, and so forth. At the top of this food chain are apex predators such as lions. Many predators however eat from multiple levels of the food chain; a carnivore may eat both secondary and tertiary consumers.

Predators must also contend with intraguild predation, where other predators kill and eat them. For example, coyotes compete with and sometimes kill gray foxes and bobcats.

Biodiversity maintained by apex predation

Predators may increase the biodiversity of communities by preventing a single species from becoming dominant. Such predators are known as keystone species and may have a profound influence on the balance of organisms in a particular ecosystem.

Introduction or removal of this predator, or changes in its population

density, can have drastic cascading effects on the equilibrium of many

other populations in the ecosystem. For example, grazers of a grassland

may prevent a single dominant species from taking over.

Riparian willow recovery at Blacktail Creek, Yellowstone National Park, after reintroduction of wolves, the local keystone species and apex predator. Left, in 2002; right, in 2015

The elimination of wolves from Yellowstone National Park had profound impacts on the trophic pyramid.

In that area, wolves are both keystone species and apex predators.

Without predation, herbivores began to over-graze many woody browse

species, affecting the area's plant populations. In addition, wolves

often kept animals from grazing near streams, protecting the beavers'

food sources. The removal of wolves had a direct effect on the beaver

population, as their habitat became territory for grazing. Increased

browsing on willows and conifers

along Blacktail Creek due to a lack of predation caused channel

incision because the reduced beaver population was no longer able to

slow the water down and keep the soil in place. The predators were thus

demonstrated to be of vital importance in the ecosystem.

Population dynamics

Harvest of Canada lynx pelts from 1825 to 2002

In the absence of predators, the population of a species can grow exponentially until it approaches the carrying capacity of the environment. Predators limit the growth of prey both by consuming them and by changing their behavior.

Increases or decreases in the prey population can also lead to

increases or decreases in the number of predators, for example, through

an increase in the number of young they bear.

Cyclical fluctuations have been seen in populations of predator

and prey, often with offsets between the predator and prey cycles. A

well-known example is that of the snowshoe hare and lynx. Over a broad span of boreal forests

in Alaska and Canada, the hare populations fluctuate in near synchrony

with a 10-year period, and the lynx populations fluctuate in response.

This was first seen in historical records of animals caught by fur hunters for the Hudson Bay Company over more than a century.

Predator-prey population cycles in a Lotka‑Volterra model

A simple model of a system with one species each of predator and prey, the Lotka–Volterra equations, predicts population cycles.

However, attempts to reproduce the predictions of this model in the

laboratory have often failed; for example, when the protozoan Didinium nasutum is added to a culture containing its prey, Paramecium caudatum, the latter is often driven to extinction.

The Lotka-Volterra equations rely on several simplifying assumptions, and they are structurally unstable, meaning that any change in the equations can stabilize or destabilize the dynamics. For example, one assumption is that predators have a linear functional response

to prey: the rate of kills increases in proportion to the rate of

encounters. If this rate is limited by time spent handling each catch,

then prey populations can reach densities above which predators cannot

control them.

Another assumption is that all prey individuals are identical. In

reality, predators tend to select young, weak, and ill individuals,

leaving prey populations able to regrow.

Many factors can stabilize predator and prey populations.

One example is the presence of multiple predators, particularly

generalists that are attracted to a given prey species if it is abundant

and look elsewhere if it is not. As a result, population cycles are only found in northern temperate and subarctic ecosystems because the food webs are simpler. The snowshoe hare-lynx system is subarctic, but even this involves other predators, including coyotes, goshawks and great horned owls, and the cycle is reinforced by variations in the food available to the hares.

A range of mathematical models have been developed by relaxing

the assumptions made in the Lotka-Volterra model; these variously allow

animals to have geographic distributions, or to migrate; to have differences between individuals, such as sexes and an age structure, so that only some individuals reproduce; to live in a varying environment, such as with changing seasons; and analysing the interactions of more than just two species at once. Such models predict widely differing and often chaotic predator-prey population dynamics. The presence of refuge areas, where prey are safe from predators, may enable prey to maintain larger populations but may also destabilize the dynamics.

Evolutionary history

Predation predates the rise of commonly recognized carnivores by

hundreds of millions (perhaps billions) of years. Predation has evolved

repeatedly in different groups of organisms. The rise of eukaryotic

cells at around 2.7 Gya, the rise of multicellular organisms at about 2

Gya, and the rise of mobile predators (around 600 Mya - 2 Gya, probably

around 1 Gya) have all been attributed to early predatory behavior,and

many very early remains show evidence of boreholes or other markings

attributed to small predator species. It likely triggered major evolutionary transitions including the arrival of cells, eukaryotes, sexual reproduction, multicellularity, increased size, mobility (including insect flight) and armoured shells and exoskeletons.

The earliest predators were microbial organisms, which engulfed

or grazed on others. Because the fossil record is poor, these first

predators could date back anywhere between 1 and over 2.7 Gya (billion

years ago). Predation visibly became important shortly before the Cambrian period—around 550 million years ago—as evidenced by the almost simultaneous development of calcification in animals and algae, and predation-avoiding burrowing. However, predators had been grazing on micro-organisms since at least 1,000 million years ago, with evidence of selective (rather than random) predation from a similar time.

The fossil record

demonstrates a long history of interactions between predators and their

prey from the Cambrian period onwards, showing for example that some

predators drilled through the shells of bivalve and gastropod molluscs, while others ate these organisms by breaking their shells.

Among the Cambrian predators were invertebrates like the anomalocaridids with appendages suitable for grabbing prey, large compound eyes and jaws made of a hard material like that in the exoskeleton of an insect.

Some of the first fish to have jaws were the armoured and mainly predatory placoderms of the Silurian to Devonian periods, one of which, the 6 m (20 ft) Dunkleosteus, is considered the world's first vertebrate "superpredator", preying upon other predators.

Insects developed the ability to fly in the Early Carboniferous or Late Devonian, enabling them among other things to escape from predators.

Among the largest predators that have ever lived were the theropod dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus from the Cretaceous period. They preyed upon herbivorous dinosaurs such as hadrosaurs, ceratopsians and ankylosaurs.

- The Cambrian substrate revolution saw life on the sea floor change from minimal burrowing (left) to a diverse burrowing fauna (right), probably to avoid new Cambrian predators.

- Dunkleosteus, a Devonian placoderm, perhaps the world's first vertebrate superpredator, reconstruction

- Meganeura monyi, a predatory Carboniferous insect related to dragonflies, could fly to escape terrestrial predators. Its large size, with a wingspan of 65 cm (30 in), may reflect the lack of vertebrate aerial predators at that time.

- Tyrannosaurus, a large theropod dinosaur of the Jurassic and Cretaceous, reconstruction

In human society

San hunter, Botswana

Humans are to some extent predatory, using weapons and tools to fish, hunt and trap animals. They also use other predatory species such as dogs, cormorants, and falcons to catch prey for food or for sport.

Two mid-sized predators, dogs and cats, are the animals most often kept as pets in western societies.

Neolithic hunters, including the San of southern Africa, used persistence hunting, a form of pursuit predation where the pursuer may be slower than prey such as a kudu

antelope over short distances, but follows it in the midday heat until

it is exhausted, a pursuit that can take up to five hours.

In biological pest control,

predators (and parasitoids) from a pest's natural range are introduced

to control populations, at the risk of causing unforeseen problems.

Natural predators, provided they do no harm to non-pest species, are an

environmentally friendly and sustainable way of reducing damage to crops

and an alternative to the use of chemical agents such as pesticides.

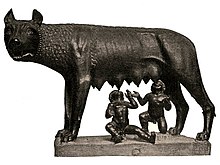

The Capitoline Wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, the mythical founders of Rome

In film, the idea of the predator as a dangerous if humanoid enemy is used in the 1987 science fiction horror action film Predator and its three sequels. A terrifying predator, a gigantic man-eating great white shark, is central, too, to Steven Spielberg's 1974 thriller Jaws.

In poetry, Ted Hughes's vigorous writings on animals, such as Pike, imaginatively explore a predator's consciousness.

In mythology and folk fable, predators such as the fox and wolf have mixed reputations.

The fox was a symbol of fertility in ancient Greece, but a weather

demon in northern Europe, and a creature of the devil in early

Christianity; the fox is sly, greedy, and cunning in fables from Aesop onwards. The big bad wolf is known to children in tales such as Little Red Riding Hood, but is a demonic figure in the Icelandic Edda sagas, where the wolf Fenrir appears in the apocalyptic ending of the world. In the middle ages, belief spread in werewolves, men transformed into wolves. In ancient Rome, and in ancient Egypt, the wolf was worshipped, the she-wolf appearing in the founding myth of Rome, suckling Romulus and Remus. More recently, in Rudyard Kipling's 1894 The Jungle Book, Mowgli is raised by the wolf pack. Attitudes to large predators in North America, such as wolf, grizzly bear

and cougar, have shifted from hostility or ambivalence, accompanied by

active persecution, towards positive and protective in the second half

of the 20th century.