Marxism uses a methodology, now known as historical materialism, to analyze and critique the development of class society and especially of capitalism as well as the role of class struggles in systemic economic, social, and political change.

According to Marxist theory, in capitalist societies, class conflict arises due to contradictions between the material interests of the oppressed and exploited proletariat—a class of wage labourers employed to produce goods and services—and the bourgeoisie—the ruling class that owns the means of production and extracts its wealth through appropriation of the surplus product produced by the proletariat in the form of profit.

This class struggle that is commonly expressed as the revolt of a society's productive forces against its relations of production, results in a period of short-term crises as the bourgeoisie struggle to manage the intensifying alienation of labor experienced by the proletariat, albeit with varying degrees of class consciousness.

In periods of deep crisis, the resistance of the oppressed can culminate in a proletarian revolution which, if victorious, leads to the establishment of socialism—a socioeconomic system based on social ownership of the means of production, distribution based on one's contribution and production organized directly for use. As the productive forces continued to advance, Marx hypothesized that socialism would ultimately be transformed into a communist society: a classless, stateless, humane society based on common ownership and the underlying principle: "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs".

Marxism has developed into many different branches and schools of thought, with the result that there is now no single definitive Marxist theory. Different Marxian schools place a greater emphasis on certain aspects of classical Marxism while rejecting or modifying other aspects. Many schools of thought have sought to combine Marxian concepts and non-Marxian concepts, which has then led to contradicting conclusions. However, lately there is movement toward the recognition that historical materialism and dialectical materialism remains the fundamental aspect of all Marxist schools of thought.

Marxism has had a profound impact on global academia and has influenced many fields such as archaeology, anthropology, media studies, political science, theater, history, sociology, art history and theory, cultural studies, education, economics, ethics, criminology, geography, literary criticism, aesthetics, film theory, critical psychology and philosophy.

According to Marxist theory, in capitalist societies, class conflict arises due to contradictions between the material interests of the oppressed and exploited proletariat—a class of wage labourers employed to produce goods and services—and the bourgeoisie—the ruling class that owns the means of production and extracts its wealth through appropriation of the surplus product produced by the proletariat in the form of profit.

This class struggle that is commonly expressed as the revolt of a society's productive forces against its relations of production, results in a period of short-term crises as the bourgeoisie struggle to manage the intensifying alienation of labor experienced by the proletariat, albeit with varying degrees of class consciousness.

In periods of deep crisis, the resistance of the oppressed can culminate in a proletarian revolution which, if victorious, leads to the establishment of socialism—a socioeconomic system based on social ownership of the means of production, distribution based on one's contribution and production organized directly for use. As the productive forces continued to advance, Marx hypothesized that socialism would ultimately be transformed into a communist society: a classless, stateless, humane society based on common ownership and the underlying principle: "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs".

Marxism has developed into many different branches and schools of thought, with the result that there is now no single definitive Marxist theory. Different Marxian schools place a greater emphasis on certain aspects of classical Marxism while rejecting or modifying other aspects. Many schools of thought have sought to combine Marxian concepts and non-Marxian concepts, which has then led to contradicting conclusions. However, lately there is movement toward the recognition that historical materialism and dialectical materialism remains the fundamental aspect of all Marxist schools of thought.

Marxism has had a profound impact on global academia and has influenced many fields such as archaeology, anthropology, media studies, political science, theater, history, sociology, art history and theory, cultural studies, education, economics, ethics, criminology, geography, literary criticism, aesthetics, film theory, critical psychology and philosophy.

Etymology

The term "Marxism" was popularized by Karl Kautsky, who considered himself an "orthodox" Marxist during the dispute between the orthodox and revisionist followers of Marx. Kautsky's revisionist rival Eduard Bernstein also later adopted use of the term. Engels did not support the use of the term "Marxism" to describe either Marx's or his views. Engels claimed that the term was being abusively used as a rhetorical qualifier by those attempting to cast themselves as "real" followers of Marx while casting others in different terms, such as "Lassallians". In 1882, Engels claimed that Marx had criticized self-proclaimed "Marxist" Paul Lafargue, by saying that if Lafargue's views were considered "Marxist", then "one thing is certain and that is that I am not a Marxist".Overview

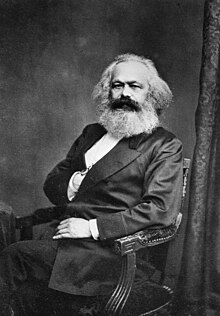

Karl Marx (1818–1883)

Marxism analyzes the material conditions and the economic activities required to fulfill human material needs to explain social phenomena within any given society.

It assumes that the form of economic organization, or mode of production,

influences all other social phenomena—including wider social relations,

political institutions, legal systems, cultural systems, aesthetics,

and ideologies. The economic system and these social relations form a base and superstructure.

As forces of production, i.e. technology, improve, existing forms of organizing production become obsolete and hinder further progress. As Karl Marx

observed: "At a certain stage of development, the material productive

forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of

production or—this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms—with

the property relations within the framework of which they have operated

hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these

relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social

revolution".

These inefficiencies manifest themselves as social contradictions in

society which are, in turn, fought out at the level of the class struggle.

Under the capitalist mode of production, this struggle materializes between the minority (the bourgeoisie) who own the means of production and the vast majority of the population (the proletariat) who produce goods and services. Starting with the conjectural premise that social change occurs because of the struggle between different classes within society who are under contradiction against each other, a Marxist would conclude that capitalism exploits and oppresses the proletariat, therefore capitalism will inevitably lead to a proletarian revolution.

Marxian economics

and its proponents view capitalism as economically unsustainable and

incapable of improving the living standards of the population due to its

need to compensate for falling rates of profit by cutting employee's wages, social benefits and pursuing military aggression. The socialist system would succeed capitalism as humanity's mode of production through workers' revolution. According to Marxian crisis theory, socialism is not an inevitability, but an economic necessity.

In a socialist society, private property—in

the form of the means of production—would be replaced by co-operative

ownership. A socialist economy would not base production on the creation

of private profits, but on the criteria of satisfying human needs—that

is, production would be carried out directly for use. As Friedrich Engels

said: "Then the capitalist mode of appropriation in which the product

enslaves first the producer, and then appropriator, is replaced by the

mode of appropriation of the product that is based upon the nature of

the modern means of production; upon the one hand, direct social

appropriation, as means to the maintenance and extension of production

on the other, direct individual appropriation, as means of subsistence

and of enjoyment".

Historical materialism

The discovery of the materialist conception of history, or rather, the consistent continuation and extension of materialism into the domain of social phenomenon, removed two chief defects of earlier historical theories. In the first place, they at best examined only the ideological motives of the historical activity of human beings, without grasping the objective laws governing the development of the system of social relations ... in the second place, the earlier theories did not cover the activities of the masses of the population, whereas historical materialism made it possible for the first time to study with the accuracy of the natural sciences the social conditions of the life of the masses and the changes in these conditions.— Russian Marxist theoretician and revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, 1913

Society does not consist of individuals, but expresses the sum of interrelations, the relations within which these individuals stand.

— Karl Marx, Grundrisse, 1858

The materialist theory of history

analyses the underlying causes of societal development and change from

the perspective of the collective ways that humans make their living.

All constituent features of a society (social classes, political

pyramid, ideologies) are assumed to stem from economic activity, an idea

often portrayed with the metaphor of the base and superstructure.

The base and superstructure metaphor describes the totality of

social relations by which humans produce and re-produce their social

existence. According to Marx: "The sum total of the forces of production

accessible to men determines the condition of society" and forms a

society's economic base. The base includes the material forces of

production, that is the labour and material means of production and

relations of production, i.e., the social and political arrangements

that regulate production and distribution. From this base rises a

superstructure of legal and political "forms of social consciousness" of

political and legal institutions that derive from the economic base

that conditions the superstructure and a society's dominant ideology.

Conflicts between the development of material productive forces and the

relations of production provokes social revolutions and thus the

resultant changes to the economic base will lead to the transformation

of the superstructure.

This relationship is reflexive, as at first the base gives rise to the

superstructure and remains the foundation of a form of social

organization, hence that formed social organization can act again upon

both parts of the base and superstructure so that the relationship is

not static but a dialectic,

expressed and driven by conflicts and contradictions. As Engels

clarified: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history

of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and

serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed,

stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on uninterrupted,

now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a

revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin

of the contending classes".

Marx considered class conflicts as the driving force of human

history since these recurring conflicts have manifested themselves as

distinct transitional stages of development in Western Europe.

Accordingly, Marx designated human history as encompassing four stages

of development in relations of production:

- Primitive communism: as in co-operative tribal societies.

- Slave society: a development of tribal to city-state; aristocracy is born.

- Feudalism: aristocrats are the ruling class; merchants evolve into capitalists.

- Capitalism: capitalists are the ruling class, who create and employ the proletariat.

Criticism of capitalism

According to the Marxist theoretician and revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, "the principal content of Marxism" was "Marx's economic doctrine".

Marx believed that the capitalist bourgeois and their economists were

promoting what he saw as the lie that "the interests of the capitalist

and of the worker are ... one and the same", therefore he believed that

they did this by purporting the concept that "the fastest possible

growth of productive capital" was best not only for the wealthy capitalists but also for the workers because it provided them with employment.

Exploitation is a matter of surplus labour—the

amount of labour one performs beyond what one receives in goods.

Exploitation has been a socioeconomic feature of every class society and

is one of the principal features distinguishing the social classes. The

power of one social class to control the means of production enables its exploitation of the other classes.

In capitalism, the labour theory of value is the operative concern; the value of a commodity equals the socially necessary labour time required to produce it. Under that condition, surplus value

(the difference between the value produced and the value received by a

labourer) is synonymous with the term "surplus labour", thus capitalist

exploitation is realised as deriving surplus value from the worker.

In pre-capitalist economies, exploitation of the worker was

achieved via physical coercion. In the capitalist mode of production,

that result is more subtly achieved and because workers do not own the

means of production, they must voluntarily enter into an exploitive work

relationship with a capitalist in order to earn the necessities of

life. The worker's entry into such employment is voluntary in that they

choose which capitalist to work for. However, the worker must work or

starve, thus exploitation is inevitable and the "voluntary" nature of a

worker participating in a capitalist society is illusory.

Alienation is the estrangement of people from their humanity (German: Gattungswesen,

"species-essence", "species-being"), which is a systematic result of

capitalism. Under capitalism, the fruits of production belong to the

employers, who expropriate the surplus created by others and so generate

alienated labourers.

In Marx's view, alienation is an objective characterization of the

worker's situation in capitalism—his or her self-awareness of this

condition is not prerequisite.

Social classes

Marx distinguishes social classes on the basis of two criteria: ownership of means of production and control over the labour power of others. Following this criterion of class based on property relations, Marx identified the social stratification of the capitalist mode of production with the following social groups:

- Proletariat: "[...] the class of modern wage labourers who, having no means of production of their own, are reduced to selling their labour power in order to live." The capitalist mode of production establishes the conditions enabling the bourgeoisie to exploit the proletariat because the workers' labour generates a surplus value greater than the workers' wages.

- Bourgeoisie:

those who "own the means of production" and buy labour power from the

proletariat, thus exploiting the proletariat. They subdivide as

bourgeoisie and the petite bourgeoisie.

- Petite bourgeoisie are those who work and can afford to buy little labour power i.e. small business owners, peasant landlords, trade workers and the like. Marxism predicts that the continual reinvention of the means of production eventually would destroy the petite bourgeoisie, degrading them from the middle class to the proletariat.

- Lumpenproletariat: the outcasts of society such as the criminals, vagabonds, beggars, or prostitutes without any political or class consciousness. Having no interest in international or national economics affairs, Marx claimed that this specific sub-division of the proletariat would play no part in the eventual social revolution.

- Landlords: a historically important social class who retain some wealth and power.

- Peasantry and farmers: a scattered class incapable of organizing and effecting socio-economic change, most of whom would enter the proletariat while some would become landlords.

Class consciousness

denotes the awareness—of itself and the social world—that a social

class possesses and its capacity to rationally act in their best

interests, hence class consciousness is required before they can effect a

successful revolution and thus the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Without defining ideology,

Marx used the term to describe the production of images of social

reality. According to Engels, "ideology is a process accomplished by the

so-called thinker consciously, it is true, but with a false consciousness.

The real motive forces impelling him remain unknown to him; otherwise

it simply would not be an ideological process. Hence he imagines false

or seeming motive forces".

Because the ruling class controls the society's means of production,

the superstructure of society (the ruling social ideas), are determined

by the best interests of the ruling class. In The German Ideology,

he says "[t]he ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling

ideas, i.e., the class which is the ruling material force of society,

is, at the same time, its ruling intellectual force."

The term "political economy"

initially referred to the study of the material conditions of economic

production in the capitalist system. In Marxism, political economy is

the study of the means of production, specifically of capital and how

that manifests as economic activity.

Marxism taught me what society was. I was like a blindfolded man in a forest, who doesn't even know where north or south is. If you don't eventually come to truly understand the history of the class struggle, or at least have a clear idea that society is divided between the rich and the poor, and that some people subjugate and exploit other people, you're lost in a forest, not knowing anything. — Cuban revolutionary and Marxist–Leninist politician Fidel Castro on discovering Marxism, 2009

This new way of thinking was invented because socialists believed

that common ownership of the "means of production" (that is the

industries, the land, the wealth of nature, the trade apparatus, the

wealth of the society, etc.) will abolish the exploitative working

conditions experienced under capitalism. Through working class

revolution, the state (which Marxists see as a weapon for the

subjugation of one class by another) is seized and used to suppress the

hitherto ruling class of capitalists and by implementing a

commonly-owned, democratically controlled workplace create the society

of communism, which Marxists see as true democracy. An economy based on

co-operation on human need and social betterment, rather than

competition for profit of many independently acting profit seekers,

would also be the end of class society, which Marx saw as the

fundamental division of all hitherto existing history.

Marx saw work, the effort by humans to transform the environment for their needs, as a fundamental feature of human kind. Capitalism,

in which the product of the worker's labor is taken from them and sold

at market rather than being part of the worker's life, is therefore

alienating to the worker. Additionally, the worker is compelled by

various means (some nicer than others) to work harder, faster and for

longer hours. While this is happening, the employer is constantly trying

to save on labor costs: pay the workers less, figure out how to use

cheaper equipment, etc. This allows the employer to extract the largest

mount of work (and therefore potential wealth) from their workers. The

fundamental nature of capitalist society is no different from that of

slave society: one small group of society exploiting the larger group.

Through common ownership of the means of production, the profit motive

is eliminated and the motive of furthering human flourishing is

introduced. Because the surplus produced by the workers is property of

the society as whole, there are no classes of producers and

appropriators. Additionally, the state, which has its origins in the

bands of retainers hired by the first ruling classes to protect their

economic privilege, will disappear as its conditions of existence have disappeared.

Revolution, socialism and communism

Leftist protester wielding a red flag with a raised fist, both are symbols of revolutionary socialism.

According to orthodox Marxist theory, the overthrow of capitalism by a socialist revolution

in contemporary society is inevitable. While the inevitability of an

eventual socialist revolution is a controversial debate among many

different Marxist schools of thought, all Marxists believe socialism is a

necessity, if not inevitable. Marxists believe that a socialist society

is far better for the majority of the populace than its capitalist

counterpart. Prior to the Russian revolution

of 1917, Lenin wrote: "The socialization of production is bound to lead

to the conversion of the means of production into the property of

society ... This conversion will directly result in an immense increase

in productivity of labour, a reduction of working hours, and the

replacement of the remnants, the ruins of small-scale, primitive,

disunited production by collective and improved labour".

The failure of the 1905 revolution and the failure of socialist

movements to resist the outbreak of World War One led to renewed

theoretical effort and valuable contributions from Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg towards an appreciation of Marx's crisis theory and efforts to formulate a theory of imperialism.

Classical Marxism

"Classical Marxism" denotes the collection of socio-eco-political

theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. "Marxism", as Ernest Mandel

remarked, "is always open, always critical, always self-critical". As

such, classical Marxism distinguishes between "Marxism" as broadly

perceived and "what Marx believed", thus in 1883 Marx wrote to the

French labour leader Jules Guesde and to Marx's son-in-law Paul Lafargue—both

of whom claimed to represent Marxist principles—accusing them of

"revolutionary phrase-mongering" and of denying the value of reformist

struggle.

From Marx's letter derives the paraphrase:

"If that is Marxism, then I am not a Marxist".

American Marxist scholar Hal Draper responded to this comment by saying:

"There are few thinkers in modern history whose thought has been so badly misrepresented, by Marxists and anti-Marxists alike".

On the other hand, the book Communism: The Great Misunderstanding

argues that the source of such misrepresentations lies in ignoring the

philosophy of Marxism, which is dialectical materialism. In large, this

was due to the fact that The German Ideology, in which Marx and Engels developed this philosophy, did not find a publisher for almost one hundred years.

Academic Marxism

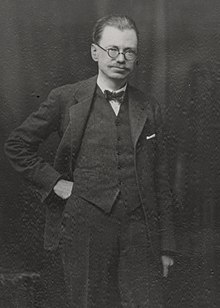

One of the 20th century's most prominent Marxist academics, the Australian archaeologist V. Gordon Childe

Marxism has been adopted by a large number of academics and other scholars working in various disciplines.

The theoretical development of Marxist archaeology

was first developed in the Soviet Union in 1929, when a young

archaeologist named Vladislav I. Ravdonikas (1894–1976) published a

report entitled "For a Soviet history of material culture". Within this

work, the very discipline of archaeology as it then stood was criticised

as being inherently bourgeois, therefore anti-socialist and so, as a

part of the academic reforms instituted in the Soviet Union under the

administration of Premier Joseph Stalin, a great emphasis was placed on the adoption of Marxist archaeology throughout the country.

These theoretical developments were subsequently adopted by

archaeologists working in capitalist states outside of the Leninist

bloc, most notably by the Australian academic V. Gordon Childe (1892–1957), who used Marxist theory in his understandings of the development of human society.

Marxist sociology is the study of sociology from a Marxist perspective. Marxist sociology is "a form of conflict theory associated with ... Marxism's objective of developing a positive (empirical) science of capitalist society as part of the mobilization of a revolutionary working class". The American Sociological Association has a section dedicated to the issues of Marxist sociology that is "interested in examining how insights from Marxist methodology and Marxist analysis can help explain the complex dynamics of modern society". Influenced by the thought of Karl Marx, Marxist sociology emerged during the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. As well as Marx, Max Weber and Émile Durkheim are considered seminal influences in early sociology. The first Marxist school of sociology was known as Austro-Marxism, of which Carl Grünberg and Antonio Labriola were among its most notable members. During the 1940s, the Western Marxist school became accepted within Western academia, subsequently fracturing into several different perspectives such as the Frankfurt School or critical theory. Due to its former state-supported position, there has been a backlash against Marxist thought in post-communist states (see sociology in Poland) but it remains dominant in the sociological research sanctioned and supported by those communist states that remain (see sociology in China).

Marxian economics refers to a school of economic thought tracing its foundations to the critique of classical political economy first expounded upon by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxian economics concerns itself with the analysis of crisis in capitalism, the role and distribution of the surplus product and surplus value in various types of economic systems, the nature and origin of economic value, the impact of class and class struggle on economic and political processes, and the process of economic evolution. Although the Marxian school is considered heterodox,

ideas that have come out of Marxian economics have contributed to

mainstream understanding of the global economy. Certain concepts of

Marxian economics, especially those related to capital accumulation and the business cycle, such as creative destruction, have been fitted for use in capitalist systems.

Marxist historiography is a school of historiography influenced by Marxism. The chief tenets of Marxist historiography are the centrality of social class and economic constraints in determining historical outcomes. Marxist historiography has made contributions to the history of the working class, oppressed nationalities, and the methodology of history from below. Friedrich Engels' most important historical contribution was Der deutsche Bauernkrieg (The German Peasants' War), which analysed social warfare in early Protestant Germany in terms of emerging capitalist classes. The German Peasants' War indicate the Marxist interest in history from below and class analysis, and attempts a dialectical analysis. Engels' short treatise The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 (1870s) was salient in creating the socialist impetus in British politics. Marx's most important works on social and political history include The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, The Communist Manifesto, The German Ideology, and those chapters of Das Kapital dealing with the historical emergence of capitalists and proletarians from pre-industrial English society. Marxist historiography suffered in the Soviet Union, as the government requested overdetermined historical writing. Notable histories include the Short Course History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolshevik), published in the 1930s to justify the nature of Bolshevik party life under Joseph Stalin. A circle of historians inside the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) formed in 1946. While some members of the group (most notably Christopher Hill and E. P. Thompson) left the CPGB after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the common points of British Marxist historiography continued in their works. Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class is one of the works commonly associated with this group. Eric Hobsbawm's Bandits is another example of this group's work. C. L. R. James was also a great pioneer of the 'history from below' approach. Living in Britain when he wrote his most notable work The Black Jacobins (1938), he was an anti-Stalinist Marxist and so outside of the CPGB. In India, B. N. Datta and D. D. Kosambi are considered the founding fathers of Marxist historiography. Today, the senior-most scholars of Marxist historiography are R. S. Sharma, Irfan Habib, Romila Thapar, D. N. Jha and K. N. Panikkar, most of whom are now over 75 years old.

Marxist literary criticism is a loose term describing literary criticism

based on socialist and dialectic theories. Marxist criticism views

literary works as reflections of the social institutions from which they

originate. According to Marxists, even literature itself is a social

institution and has a specific ideological function, based on the

background and ideology of the author. Notable marxist literary critics

include Mikhail Bakhtin, Walter Benjamin, Terry Eagleton and Fredric Jameson. Marxist aesthetics is a theory of aesthetics based on, or derived from, the theories of Karl Marx. It involves a dialectical and materialist, or dialectical materialist,

approach to the application of Marxism to the cultural sphere,

specifically areas related to taste such as art, beauty, etc. Marxists

believe that economic and social conditions, and especially the class

relations that derive from them, affect every aspect of an individual's

life, from religious beliefs to legal systems to cultural frameworks.

Some notable Marxist aestheticians include Anatoly Lunacharsky, Mikhail Lifshitz, William Morris, Theodor W. Adorno, Bertolt Brecht, Herbert Marcuse, Walter Benjamin, Antonio Gramsci, Georg Lukács, Louis Althusser, Jacques Rancière, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Raymond Williams.

According to a 2007 survey of American professors by Neil Gross

and Solon Simmons, 17.6% of social science professors and 5.0% of

humanities professors identify as Marxists, while between 0 and 2% of

professors in all other disciplines identify as Marxists.

History

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

Karl Marx (5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political economist and socialist revolutionary who addressed the matters of alienation and exploitation of the working class, the capitalist mode of production

and historical materialism. He is famous for analysing history in terms

of class struggle, summarised in the initial line introducing The Communist Manifesto (1848): "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles".

Friedrich Engels (28 November 1820 – 5 August 1895) was a German political philosopher

who together with Marx co-developed communist theory. Marx and Engels

first met in September 1844. Discovering that they had similar views of

philosophy and socialism, they collaborated and wrote works such as Die heilige Familie (The Holy Family). After Marx was deported from France in January 1845, they moved to Belgium, which then permitted greater freedom of expression than other European countries. In January 1846, they returned to Brussels to establish the Communist Correspondence Committee.

In 1847, they began writing The Communist Manifesto (1848), based on Engels' The Principles of Communism. Six weeks later, they published the 12,000-word pamphlet in February 1848. In March, Belgium expelled them and they moved to Cologne, where they published the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, a politically radical

newspaper. By 1849, they had to leave Cologne for London. The Prussian

authorities pressured the British government to expel Marx and Engels,

but Prime Minister Lord John Russell refused.

After Marx's death in 1883, Engels became the editor and translator of Marx's writings. With his Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884) – analysing monogamous marriage

as guaranteeing male social domination of women, a concept analogous,

in communist theory, to the capitalist class's economic domination of

the working class—Engels made intellectually significant contributions to feminist theory and Marxist feminism.

Late 20th century

Fidel Castro at the UN General Assembly, 1960

In 1959, the Cuban Revolution led to the victory of Fidel Castro and his July 26 Movement. Although the revolution was not explicitly socialist, upon victory Castro ascended to the position of Prime Minister and adopted the Leninist model of socialist development, forging an alliance with the Soviet Union. One of the leaders of the revolution, the Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara (1928–1967), subsequently went on to aid revolutionary socialist movements in Congo-Kinshasa and Bolivia, eventually being killed by the Bolivian government, possibly on the orders of the Central Intelligence Agency

(CIA), though the CIA agent sent to search for Guevara, Felix

Rodriguez, expressed a desire to keep him alive as a possible bargaining

tool with the Cuban government. He would posthumously go on to become

an internationally recognised icon.

In the People's Republic of China, the Maoist government undertook the Cultural Revolution from 1966 through to 1976 to ameliorate capitalist elements of Chinese society and achieve socialism. However, upon Mao Zedong's death, his rivals seized political power and under the Premiership of Deng Xiaoping (1978–1992), many of Mao's Cultural Revolution era policies were revised or abandoned and much of the state sector privatised.

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the collapse of most of those socialist states that had professed a Marxist–Leninist ideology. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the emergence of the New Right and neoliberal capitalism as the dominant ideological trends in western politics—championed by U.S. President Ronald Reagan and U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher—led

the west to take a more aggressive stand against the Soviet Union and

its Leninist allies. Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union the reformist Mikhael Gorbachev became Premier in March 1985 and sought to abandon Leninist models of development towards social democracy. Ultimately, Gorbachev's reforms, coupled with rising levels of popular ethnic nationalism in the Soviet Union, led to the state's dissolution

in late 1991 into a series of constituent nations, all of which

abandoned Marxist–Leninist models for socialism, with most converting to

capitalist economies.

21st century

Hugo Chavez casting a vote in 2007

At the turn of the 21st century, China, Cuba, Laos, North Korea and

Vietnam remained the only officially Marxist–Leninist states remaining,

although a Maoist government led by Prachanda was elected into power in Nepal in 2008 following a long guerrilla struggle.

The early 21st century also saw the election of socialist

governments in several Latin American nations, in what has come to be

known as the "pink tide". Dominated by the Venezuelan government of Hugo Chávez, this trend also saw the election of Evo Morales in Bolivia, Rafael Correa in Ecuador and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua. Forging political and economic alliances through international organisations like the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas,

these socialist governments allied themselves with Marxist–Leninist

Cuba and although none of them espoused a Leninist path directly, most

admitted to being significantly influenced by Marxist theory.

For Italian Marxist Gianni Vattimo in his 2011 book Hermeneutic Communism,

"this new weak communism differs substantially from its previous Soviet

(and current Chinese) realization, because the South American countries

follow democratic electoral procedures and also manage to decentralize

the state bureaucratic system through the Bolivarian missions.

In sum, if weakened communism is felt as a specter in the West, it is

not only because of media distortions but also for the alternative it

represents through the same democratic procedures that the West

constantly professes to cherish but is hesitant to apply".

Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping has announced a deepening commitment of the Communist Party of China

to the ideas of Marx. At an event celebrating the 200th anniversary of

Marx's birth, Xi said “We must win the advantages, win the initiative,

and win the future. We must continuously improve the ability to use

Marxism to analyse and solve practical problems...” also adding

“powerful ideological weapon for us to understand the world, grasp the

law, seek the truth, and change the world,”. Xi has further stressed the

importance of examining and continuing the tradition of the CPC and embrace its revolutionary past.

Criticism

Criticisms of Marxism have come from various political ideologies and

academic disciplines. These include general criticisms about lack of

internal consistency, criticisms related to historical materialism, that

it is a type of historical determinism, the necessity of suppression of

individual rights, issues with the implementation of communism and

economic issues such as the distortion or absence of price signals and

reduced incentives. In addition, empirical and epistemological problems

are frequently identified.

Some Marxists have criticised the academic institutionalisation of Marxism for being too shallow and detached from political action. For instance, Zimbabwean Trotskyist Alex Callinicos, himself a professional academic, stated: "Its practitioners remind one of Narcissus,

who in the Greek legend fell in love with his own reflection ...

Sometimes it is necessary to devote time to clarifying and developing

the concepts that we use, but indeed for Western Marxists this has

become an end in itself. The result is a body of writings

incomprehensible to all but a tiny minority of highly qualified

scholars".

Additionally, there are intellectual critiques of Marxism that

contest certain assumptions prevalent in Marx's thought and Marxism

after him, without exactly rejecting Marxist politics.

Other contemporary supporters of Marxism argue that many aspects of

Marxist thought are viable, but that the corpus is incomplete or

outdated in regards to certain aspects of economic, political or social theory. They may therefore combine some Marxist concepts with the ideas of other theorists such as Max Weber—the Frankfurt School is one example.

General criticisms

Philosopher and historian of ideas Leszek Kołakowski

pointed out that "Marx's theory is incomplete or ambiguous in many

places, and could be 'applied' in many contradictory ways without

manifestly infringing its principles". Specifically, he considers "the

laws of dialectics" as fundamentally erroneous, stating that some are

"truisms with no specific Marxist content", others "philosophical dogmas

that cannot be proved by scientific means" and some just "nonsense". He

believes that some Marxist laws can be interpreted differently, but

that these interpretations still in general fall into one of the two

categories of error.

Okishio's theorem

shows that if capitalists use cost-cutting techniques and real wages do

not increase, the rate of profit must rise, which casts doubt on Marx's

view that the rate of profit would tend to fall.

The allegations of inconsistency have been a large part of Marxian economics and the debates around it since the 1970s. Andrew Kliman

argues that this undermines Marx's critiques and the correction of the

alleged inconsistencies, because internally inconsistent theories cannot

be right by definition.

Epistemological and empirical critiques

Marx's predictions have been criticized because they have allegedly

failed, with some pointing towards the GDP per capita increasing

generally in capitalist economies compared to less market oriented

economics, the capitalist economies not suffering worsening economic

crises leading to the overthrow of the capitalist system and communist

revolutions not occurring in the most advanced capitalist nations, but

instead in undeveloped regions.

In his books The Poverty of Historicism and Conjectures and Refutations, philosopher of science Karl Popper, criticized the explanatory power and validity of historical materialism.

Popper believed that Marxism had been initially scientific, in that

Marx had postulated a genuinely predictive theory. When these

predictions were not in fact borne out, Popper argues that the theory

avoided falsification

by the addition of ad hoc hypotheses that made it compatible with the

facts. Because of this, Popper asserted, a theory that was initially

genuinely scientific degenerated into pseudoscientific dogma.

Socialist critiques

Democratic socialists

and social democrats reject the idea that socialism can be accomplished

only through extra-legal class conflict and a proletarian revolution.

The relationship between Marx and other socialist thinkers and

organizations—rooted in Marxism's "scientific" and anti-utopian

socialism, among other factors—has divided Marxists from other

socialists since Marx's life.

After Marx's death and with the emergence of Marxism, there have

also been dissensions within Marxism itself—a notable example is the

splitting of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party into Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. Orthodox Marxists became opposed to a less dogmatic, more innovative, or even revisionist Marxism.

Anarchist and libertarian critiques

Anarchism

has had a strained relationship with Marxism since Marx's life.

Anarchists and many non-Marxist libertarian socialists reject the need

for a transitory state phase, claiming that socialism can only be established through decentralized, non-coercive organization. Anarchist Mikhail Bakunin criticized Marx for his authoritarian bent. The phrases "barracks socialism" or "barracks communism" became a shorthand for this critique, evoking the image of citizens' lives being as regimented as the lives of conscripts in a barracks. Noam Chomsky

is critical of Marxism's dogmatic strains and the idea of Marxism

itself, but still appreciates Marx's contributions to political thought.

Unlike some anarchists, Chomsky does not consider Bolshevism "Marxism

in practice", but he does recognize that Marx was a complicated figure

who had conflicting ideas, while he also acknowledges the latent

authoritarianism in Marx he also points to the libertarian strains that

developed into the council communism of Rosa Luxemburg and Anton Pannekoek.

However, his commitment to libertarian socialism has led him to

characterize himself as an anarchist with radical Marxist leanings.

Libertarian Marxism refers to a broad scope of economic and political philosophies that emphasize the anti-authoritarian aspects of Marxism. Early currents of libertarian Marxism, known as left communism, emerged in opposition to Marxism–Leninism and its derivatives such as Stalinism, Ceaușism and Maoism. Libertarian Marxism is also often critical of reformist positions, such as those held by social democrats. Libertarian Marxist currents often draw from Marx and Engels' later works, specifically the Grundrisse and The Civil War in France, emphasizing the Marxist belief in the ability of the working class to forge its own destiny without the need for a revolutionary party or state to mediate or aid its liberation. Along with anarchism, libertarian Marxism is one of the main currents of libertarian socialism.

Economic critiques

Other critiques come from an economic standpoint. Vladimir Karpovich Dmitriev writing in 1898, Ladislaus von Bortkiewicz writing in 1906–1907 and subsequent critics have alleged that Marx's value theory and law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall

are internally inconsistent. In other words, the critics allege that

Marx drew conclusions that actually do not follow from his theoretical

premises. Once these alleged errors are corrected, his conclusion that

aggregate price and profit are determined by and equal to aggregate

value and surplus value no longer holds true. This result calls into

question his theory that the exploitation of workers is the sole source

of profit.

Both Marxism and socialism have received considerable critical analysis from multiple generations of Austrian economists in terms of scientific methodology, economic theory and political implications. During the marginal revolution, subjective value theory was rediscovered by Carl Menger, a development that fundamentally undermined the British cost theories of value. The restoration of subjectivism and praxeological methodology previously used by classical economists including Richard Cantillon, Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, Jean-Baptiste Say and Frédéric Bastiat led Menger to criticise historicist methodology in general. Second-generation Austrian economist Eugen Böhm von Bawerk

used praxeological and subjectivist methodology to attack the law of

value fundamentally. Non-Marxist economists have regarded his criticism

as definitive, with Gottfried Haberler

arguing that Böhm-Bawerk's critique of Marx's economics was so thorough

and devastating that as of the 1960s no Marxian scholar had

conclusively refuted it. Third-generation Austrian Ludwig von Mises rekindled debate about the economic calculation problem

by identifying that without price signals in capital goods, all other

aspects of the market economy are irrational. This led him to declare

that "rational economic activity is impossible in a socialist commonwealth".

Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson

argue that Marx's economic theory was fundamentally flawed because it

attempted to simplify the economy into a few general laws that ignored

the impact of institutions on the economy.