| Neanderthal | |

|---|---|

| |

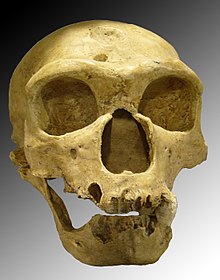

| Late Neanderthal skull (La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1) | |

| |

| An approximate reconstruction of a Neanderthal skeleton. The central rib cage, including the sternum, and parts of the pelvis are from modern humans. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: |

†H. neanderthalensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo neanderthalensis

King, 1864

| |

| |

| Known Neanderthal range in Europe (blue), Southwest Asia (orange), Uzbekistan (green), and the Altai mountains (violet). | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Homo stupidus (Haeckel 1866) Homo mousteriensis (Klaatsch 1909) Palaeoanthropus neanderthalensis | |

Neanderthals, Homo neanderthalensis or Homo sapiens neanderthalensis) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans in the genus Homo, who lived within Eurasia from circa 400,000 until 40,000 years ago.

Currently the earliest fossils of Neanderthals in Europe are dated between 450,000 and 430,000 years ago, and thereafter Neanderthals expanded into Southwest and Central Asia. They are known from numerous fossils, as well as stone tool assemblages. Almost all assemblages younger than 160,000 years are of the so-called Mousterian techno-complex, which is characterised by tools made out of stone flakes. The type specimen is Neanderthal 1, found in Neander Valley in the German Rhineland, in 1856.

Compared to modern humans, Neanderthals were stockier, with shorter legs and bigger bodies. In conformance with Bergmann's rule, as well as Allen's rule, this was likely was an adaptation to preserve heat in cold climates. Male and female Neanderthals had cranial capacities averaging 1,600 cm3 (98 cu in) and 1,300 cm3 (79 cu in), respectively, within the range of the values for anatomically modern humans. Average males stood around 164 to 168 cm (65 to 66 in) and females 152 to 156 cm (60 to 61 in) tall.

There has been growing evidence for admixture between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans, reflected in the genomes of all modern non-African populations but not in the genomes of most sub-Saharan Africans. This suggests that interbreeding between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans took place after the recent "out of Africa" migration, around 70,000 years ago. Recent admixture analyses have added to the complexity, finding that Eastern Neanderthals derived up to 2% of their ancestry from anatomically modern humans who left Africa some 100,000 years ago.

Name and classification

Neanderthals are named after one of the first sites where their fossils were discovered in the mid-19th century in the Neander Valley, just east of Düsseldorf, at the time in the Rhine Province of the Kingdom of Prussia (now in Northrhine-Westphalia, Germany). The valley itself was named for Joachim Neander, Neander being the graecicized form of the surname Neumann ("new man"). The German spelling of Thal "Valley" was current in the 19th century (contemporary German Tal).Neanderthal 1 was known as the "Neanderthal cranium" or "Neanderthal skull" in anthropological literature, and the individual reconstructed on the basis of the skull was occasionally called "the Neanderthal man". The binomial name Homo neanderthalensis—extending the name "Neanderthal man" from the individual type specimen to the entire group—was first proposed by the Anglo-Irish geologist William King in a paper read to the British Association in 1863, although in the following year he stated that the specimen was not human and rejected the name. King's name had priority over the proposal put forward in 1866 by Ernst Haeckel, Homo stupidus. Popular English usage of "Neanderthal" as shorthand for "Neanderthal man", as in "the Neanderthals" or "a Neanderthal", emerged in the popular literature of the 1920s.

Since the historical spelling -th- in German represents the phoneme /t/ or /tʰ/, not the fricative /θ/, standard British pronunciation of "Neanderthal" is with /t/ (IPA: /niːˈændərtɑːl/). Because of the usual sound represented by digraph ⟨th⟩ in English, "Neanderthal" is also pronounced with the voiceless fricative /θ/, at least in "layman's American English" (as /niːˈændərθɔːl/).

The spelling Neandertal is occasionally seen in English, even in scientific publications. Since "Neanderthal", or "Neandertal", is a common name, there is no authoritative prescription on its spelling, unlike the spelling of the binominal name H. neanderthalensis, which is predicated by King 1864. The common name in German is always invariably Neandertaler (lit. "of the valley of Neander"), not Neandertal, but the spelling of the name of the Neander Valley itself (Neandertal vs. Neanderthal) has been affected by the species name, the names of the Neanderthal Museum and of Neanderthal station persisting with pre-1900 orthography.

Ever since the discovery of the Neanderthal fossils, expert opinion has been divided as to whether Neanderthals should be considered a separate species (Homo neanderthalensis) or a subspecies (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis) relative to modern humans. Pääbo (2014) described such "taxonomic wars" as unresolveable in principle, "since there is no definition of species perfectly describing the case." The question depends on the definition of Homo sapiens as a chronospecies, which has also been in flux throughout the 20th century. Authorities preferring classification of Neanderthals as subspecies have introduced the subspecies name Homo sapiens sapiens for the anatomically modern Cro-Magnon population which lived in Europe at the same time as Neanderthals, while authorities preferring classification as separate species use Homo sapiens as equivalent to "anatomically modern humans".

During the early 20th century, a prevailing view of Neanderthals as "simian", influenced by Arthur Keith and Marcellin Boule, tended to exaggerate the anatomical differences between Neanderthals and Cro Magnon. Beginning in the 1930s, revised reconstructions of Neanderthals increasingly emphasized the similarity rather than differences from modern humans. From the 1940s throughout the 1970s, it was increasingly common to use the subspecies classification of Homo sapiens neanderthalensis vs. Homo sapiens sapiens. The hypothesis of "multiregional origin" of modern man was formulated in the 1980s on such grounds, arguing for the presence of an unbroken succession of fossil sites in both Europe and Asia. Hybridization between Neanderthals and Cro Magnon had been suggested on skeletal and craniological grounds since the early 20th century, and found increasing support in the later 20th century, until Neanderthal admixture was found to be present in modern populations genetics in the 2010s.

Evolution

Stage 4: Classic European Neanderthal (La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1, 50 ka)

The evolution of Neanderthals according to the accretion model.

Both Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans were initially thought to have evolved from Homo erectus between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago. H. erectus had emerged around 1.8 million years ago, and had long been present, in various subspecies throughout Eurasia.

The divergence time between the Neanderthal and archaic Homo sapiens lineages is estimated to be between 800,000 and 400,000 years ago. The more recent time depth has been suggested by Endicott et al. (2010) and Rieux et al. (2014).

The time of divergence between archaic Homo sapiens and ancestors of Neanderthals and Denisovans caused by a population bottleneck of the latter was dated at 744,000 years ago, combined with repeated early admixture events and Denisovans diverging from Neanderthals 300 generations after their split from Homo sapiens, was calculated by Rogers et al. (2017).

Homo heidelbergensis, dated 600,000 to 300,000 years ago, has long been thought to be a likely candidate for the last common ancestor of the Neanderthal and modern human lineages. However, genetic evidence from the Sima de los Huesos fossils published in 2016 seems to suggest that H. heidelbergensis in its entirety should be included in the Neanderthal lineage, as "pre-Neanderthal" or "early Neanderthal", while the divergence time between the Neanderthal and modern lineages has been pushed back to before the emergence of H. heidelbergensis, to about 600,000 to 800,000 years ago, the approximate age of Homo antecessor.

The taxonomic distinctions between H. heidelbergensis and Neanderthals is mostly due to a fossil gap in Europe between 300,000 and 243,000 years ago (MIS 8). "Neanderthals", by conventions, are fossils which date to after this gap. The quality of the fossil record greatly increases from 130,000 years ago onwards. Specimens younger than this date make up the bulk of known Neanderthal skeletons and were the first whose anatomy was comprehensively studied. In morphological studies, the term "classic Neanderthal" may be used in a narrower sense for Neanderthals younger than 71,000 years old (MIS 4 and 3).

Microbiome

Neanderthals lived along-side humans until their extinction between 40,000-30,000 years ago, and share a common ancestor which could tell us more about how our microbiome evolved. Using dental calculus, calcified bone that traps microorganism, researchers have been able to look into how ancient human microbiomes may have existed. Based on a 16s shotgun sequence of dental calculus found in neanderthal specimens, researchers have found a large portion of neanderthal oral microbiome contains Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, much like modern humans; however, neanderthals also had, Euryarchaeota, fungi and some oral pathogens that modern humans lack.Diet of neanderthals depend on the environment they live in. Neanderthal remains recovered from Spy Cave, Belgium and examined them using dental calculus which indicated neanderthals in this area had meat based diet, including woolly rhinoceros and wild sheep. This is compared to neanderthal remains found in Spain. In El Sidrón Cave, Spain, they examined remains indicating a large amount of plant material such as nuts and moss, as well as mushrooms. Researchers determined that the difference in diets contributed to the neanderthal microbiota, and meat based diet caused the most variation. According to fecal biomarkers, neanderthals were able to convert cholesterol to coprostanol at a high rate, much like modern humans, because of the bacteria present in their gut.

Habitat and range

Approximate Neanderthal range; pre-Neanderthal and early Neanderthal range shown in magenta, late Neanderthal range in blue.

Sites where "classic Neanderthal" fossils (70–40 ka) have been found. Ice sheets of the last glacial maximum are indicated (partly ice-free during the Eemian interglacial)

Early Neanderthals, living before the Eemian interglacial

(130 ka), are poorly known and come mostly from European sites. From

130 ka onwards, the quality of the fossil record increases dramatically.

From then on, Neanderthal remains are found in Western, Central,

Eastern, and Mediterranean Europe, as well as Southwest, Central, and Northern Asia up to the Altai Mountains in Siberia. No Neanderthal has ever been found outside Central to Western Eurasia, namely neither to the south of 30°N (Shuqba, Levant), nor east of 85°E (Denisova, Siberia).

The limit of their northern range appears to have been south of

53°N (Bontnewydd, Wales),

although it is difficult to assess because glacial advances destroy most

human remains, the Bontnewydd tooth being exceptional. Middle

Palaeolithic artefacts have been found up to 60°N on the Russian plains.

Total Neanderthal effective population

size has been estimated at close to 15,000 individuals (corresponding

to a total population of roughly 150,000 individuals), living in small,

isolated, inbred groups.

Anatomy

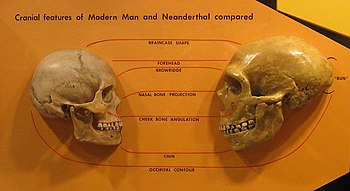

Anatomical comparison of skulls of Homo sapiens (Oase 1, left) and Homo neanderthalensis (right)

(Cleveland Museum of Natural History).

(Cleveland Museum of Natural History).

Features compared are the braincase shape, forehead, browridge, nasal bone projection, cheek bone angulation, chin and occipital contour.

Comparison of faces of early European Homo sapiens (left) and Homo neanderthalensis (right) based on forensic facial reconstructions exhibited at the Neanderthal Museum.

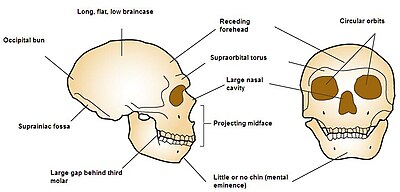

Neanderthal anatomy differed from modern humans in that they had a more robust build and distinctive morphological features, especially on the cranium, which gradually accumulated more derived aspects as it was described by Marcellin Boule,

particularly in certain isolated geographic regions. These include

shorter limb proportions, a wider, barrel-shaped rib cage, a reduced

chin, sloping forehead, and a large nose, being at the modern human

higher end in both width and length,

and started somewhat higher on the face than in modern humans. The

Neanderthal skull is typically more elongated and less globular than

that of anatomically modern humans, and features a notable occipital bun. Inherited Neanderthal DNA variants may subtly influence the skull shape of living people.

Neanderthals were much stronger than modern humans, with particularly strong arms and hands, while they were comparable in height;

based on 45 long bones from 14 males and 7 females, three different

methods of estimating height produced averages for Neanderthal males

from 164 to 168 cm (65 to 66 in) and 152 to 156 cm (60 to 61 in) for

females. Samples of 26 specimens found an average weight of 77.6 kg (171 lb) for males and 66.4 kg (146 lb) for females.

Neanderthals are known for their large cranial capacity, which at 1,600 cm3 (98 cu in) is larger on average than that of modern humans. One study has found that drainage of the dural venous sinuses

(low pressure blood vessels that run between the meninges and skull

leading down through the skull) in the occipital lobe region of

Neanderthal brains appears more asymmetric than other hominid brains.

Three-dimensional computer-assisted reconstructions of Neanderthal

infants based on fossils from Russia and Syria indicated that

Neanderthal and modern human brains were the same size at birth, but

that by adulthood, the Neanderthal brain was larger than the modern

human brain. They had almost the same degree of encephalisation (i.e. brain-to-body-size ratio) as modern humans.

Three-dimensional reconstructions of nasal cavities and computational fluid dynamics

techniques have found that Neanderthals and modern humans both adapted

their noses (independently and in a convergent way) to help breathe in

cold and dry conditions. The large nose seen in Neanderthals, as well as Homo heidelbergensis, affected the shape of the skull and the muscle attachments, and gave them a weaker bite force than in modern humans. Larger eye sockets and larger areas of the brain devoted to vision suggest that their eyesight may have been better than that of modern humans.

Dental remains from two Italian sites indicate that Neanderthal dental

features had evolved by around 450,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene epoch.

Two Neanderthal specimens from Italy and Spain were found to have an allele of the melanocortin 1 receptor

(MC1R) with reduced activity. This receptor plays a role in mammalian

pigmentation, and the activity of the novel allele in Neanderthals was

found to be reduced sufficiently to allow for visibly lighter pigment

expression.

Although not found in the small European sample studied by Lalueza et

al., a larger study found that the derived variant was present at 70%

frequency in Taiwanese Aborigines, 50% frequency in Cheyenne Native

Americans, 30% frequency in Han Chinese, and 5% frequency in Europeans.

It is therefore unclear whether this loss-of-function variant is

responsible for any other traits other than lightening the skin (such as

red or blonde hair). This allele was not found in the Croatian or Altai

Neanderthal specimens subjected to whole-genome sequencing, nor have

the MC1R variants known to cause red hair in modern humans, though the

Altai specimen was polymorphic for another variant MC1R allele of

unknown effect.

Genomic analysis of three Croatian specimens for the alleles of

numerous genes that affect pigment in modern humans showed the

Neanderthals to have more dark-pigment-producing alleles than those

producing reduced pigmentation. Based on this they concluded these

Neanderthals had darker hair, skin and eye coloration than modern

Europeans. Skin pigmentation prediction for archaic humans is a

controversial field, as there are no living samples to confirm or

identify novel SNPs.

The overall shorter limbs and in general more stout body

proportions of Neanderthals may have been an adaptation to colder

climates. In comparison to modern humans, Neanderthals were more suited

for sprinting and pouncing activities rather than endurance running,

which would have been adaptive in the forests and woodlands that seem to

have been their preferred environment. Genomic evidence possibly points

to a higher proportion of fast-twitch muscle fiber in the Neanderthal. Evidence suggests that Neanderthals walked upright much like modern humans.

Behaviour

Levallois point – Beuzeville, France

Neanderthals made stone tools, used fire,

and were hunters. This is the extent of the consensus on their

behaviour. It had long been debated whether Neanderthals were hunters or

scavengers, but the discovery of the pre-Neanderthal Schöningen wooden spears in Germany helped settle the debate in favour of hunting. A Levallois point embedded in the vertebrae of a wild ass indicated that a javelin had been thrown with a parabolic trajectory to disable the animal. Most available evidence suggests they were apex predators, and fed on red deer, reindeer, ibex, wild boar, aurochs and on occasion mammoth, straight-tusked elephant and rhinoceros. They appear to have occasionally used vegetables as fall-back food, revealed by isotope analysis of their teeth and study of their coprolites (fossilised faeces). Dental analysis of specimens from Spy, Belgium and El Sidrón, Spain

suggested that these Neanderthals had a wide-ranging diet, with no

evidence at all that the El Sidrón Neanderthals were carnivorous,

instead living on "a mixture of forest moss, pine nuts and a mushroom

known as split gill". Nonetheless, isotope

studies of Neanderthals from two French sites showed similar profiles

to other carnivores, suggesting that these populations may have eaten meat.

The Neanderthal skeleton suggests they consumed 100 to 350 kcal (420

to 1,460 kJ) more per day than modern male humans of 68.5 kg (151 lb)

and females of 59.2 kg (131 lb).

The size and distribution of Neanderthal sites, along with

genetic evidence, suggests Neanderthals lived in much smaller and more

sparsely distributed groups than anatomically-modern Homo sapiens. The bones of twelve Neanderthals were discovered at El Sidrón cave in northwestern Spain. They are thought to have been a group killed and butchered about 50,000 years ago. Analysis of the mtDNA

showed that the three adult males belonged to the same maternal

lineage, while the three adult females belonged to different ones. This

suggests a social structure where males remained in the same social

group and females "married out".

The bones of the El Sidrón group show signs of defleshing, suggesting that they were victims of cannibalism.

The St. Césaire 1 skeleton from La Roche à Pierrot, France, showed a

healed fracture on top of the skull apparently caused by a deep blade

wound, suggesting interpersonal violence.

Shanidar 3, an adult male dated to the late middle Paleolithic, was

found to have a rib lesion characteristic of projectile weapon injuries,

which some anthropologists consider evidence for interspecies conflict.

Neanderthals suffered a high rate of traumatic injury, with by

some estimates 79% of specimens showing evidence of healed major trauma.

It was thus theorized that Neanderthals employed a riskier and possibly

less sophisticated hunting strategy. However, rates of cranial trauma

are not significantly different between Neanderthal and middle

paleolithic Anatomically Modern Human samples. Both populations evidently cared for the injured and had some degree of medical knowledge.

Claims that Neanderthals deliberately buried their dead, and if they did, whether such burials had any symbolic meaning, are heavily contested. The debate on deliberate Neanderthal burials has been active since the 1908 discovery of the well-preserved Chapelle-aux-Saints 1

skeleton in a small hole in a cave in southwestern France. In this

controversy's most recent installment, a team of French researchers

reinvestigated the Chapelle-aux-Saints cave and in January 2014 reasserted the century-old claim that the 1908 Neanderthal specimen had been deliberately buried, and this has in turn been heavily criticised.

According to archaeologist John F. Hoffecker:

Neanderthal sites show no evidence of tools for making tailored clothing. There are only hide scrapers, which might have been used to make blankets or ponchos. This is in contrast to Upper Paleolithic (modern human) sites, which have an abundance of eyed bone needles and bone awls. Moreover, microwear analysis of Neanderthal hide scrapers shows that they were used only for the initial phases of hide preparation, and not for the more advanced phases of clothing production.

— John F. Hoffecker, The Spread of Modern Humans in Europe

Culture

Whether Neanderthals created art and used adornments, which would

indicate a capability for complex symbolic thought, remains unresolved. A

2010 paper on radiocarbon dates cast doubt on the association of Châtelperronian beads with Neanderthals, and Paul Mellars considered the evidence for symbolic behaviour to have been refuted. This conclusion, however, is controversial, and others such as Jean-Jacques Hublin and colleagues have re-dated material associated with the Châtelperronian artifacts and used proteomic evidence to restate the challenged association with Neanderthals.

Artist's reconstruction of a Neanderthal man with child

A large number of other claims of Neanderthal art, adornment, and

structures have been made. These are often taken by the media as showing

Neanderthals were capable of symbolic thought, or were "mental equals" to anatomically modern humans. As evidence of symbolism, none of them are widely accepted, although the same is true for Middle Palaeolithic anatomically modern humans. Among many others:

- Flower pollen on the body of pre-Neanderthal Shanidar 4, Iraq, had in 1975 been argued to be a flower burial. Once popular, this theory is no longer accepted.

- Bird bones were argued to show evidence for feather plucking in a 2012 study examining 1,699 ancient sites across Eurasia, which the authors controversially took to mean Neanderthals wore bird feathers as personal adornments.

- Deep scratches were found in 2012 on a cave floor underlying Neanderthal layer in Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, which some have controversially interpreted as art.

- Two 176,000-year-old stalagmite ring structures, several metres wide, were reported in 2016 more than 300 metres from the entrance within Bruniquel Cave, France. The authors claim artificial lighting would have been required as this part of the cave is beyond the reach of daylight and that the structures had been made by early Neanderthals, the only humans in Europe at this time.

- In 2015, a study argued that a number of 130,000-year-old eagle talons found in a cache near Krapina, Croatia along with Neanderthal bones, had been modified to be used as jewellery.

All of these appeared only in single locations. Yet in 2018, using uranium-thorium dating methods,

red painted symbols comprising a scalariform (ladder shape), a negative

hand stencil, and red lines and dots on the cave walls of three Spanish

caves 700 km (430 mi) apart were dated to at least 64,000 years old.

If the dating is correct, they were painted before the time

anatomically modern humans are thought to have arrived in Europe.

Paleoanthropologist John D. Hawks

argues these findings demonstrate Neanderthals were capable of symbolic

behaviour previously thought to be unique to modern humans.

Interbreeding with archaic and modern humans

Chris Stringer's hypothesis of the family tree of genus Homo, published 2012 in Nature – the horizontal axis represents geographic location, and the vertical axis represents time in millions of years ago.

An alternative to extinction is that Neanderthals were absorbed into the Cro-Magnon population by interbreeding. This would be counter to strict versions of the recent African origin theory, since it would imply that at least part of the genome of Europeans would descend from Neanderthals.

Pre-2010 interbreeding hypotheses

Until the early 1950s, most scholars thought Neanderthals were not in the ancestry of living humans.

Nevertheless, Thomas H. Huxley in 1904 saw among Frisians the presence

of what he suspected to be Neanderthaloid skeletal and cranial

characteristics as an evolutionary development from Neanderthal rather

than as a result of interbreeding, saying that "the blond long-heads may

exhibit one of the lines of evolution of the men of the Neanderthaloid

type," yet he raised the possibility that the Frisians alternatively

"may be the result of the admixture of the blond long-heads with

Neanderthal men," thus separating "blond" from "Neanderthaloid."

Hans Peder Steensby proposed interbreeding in 1907 in the article Race studies in Denmark. He strongly emphasised that all living humans are of mixed origins.

He held that this would best fit observations, and challenged the

widespread idea that Neanderthals were ape-like or inferior. Basing his

argument primarily on cranial data, he noted that the Danes, like the

Frisians and the Dutch, exhibit some Neanderthaloid characteristics, and

felt it was reasonable to "assume something was inherited" and that

Neanderthals "are among our ancestors."

Carleton Stevens Coon in 1962 found it likely, based upon

evidence from cranial data and material culture, that Neanderthal and

Upper Paleolithic peoples either interbred or that the newcomers

reworked Neanderthal implements "into their own kind of tools."

Christopher Thomas Cairney in 1989 went further, laying out a rationale

for hybridisation and adding a broader discussion of physical

characteristics as well as commentary on interbreeding and its

importance to adaptive European phenotypes. Cairney specifically

discussed the "intermixture of racial elements" and "hybridisation."

By the early 2000s, the majority of scholars supported the Out of Africa hypothesis,

according to which anatomically modern humans left Africa about 50,000

years ago and replaced Neanderthals with little or no interbreeding.

Yet some scholars still argued for hybridisation with Neanderthals. The

most vocal proponent of the hybridisation hypothesis was Erik Trinkaus of Washington University. Trinkaus claimed various fossils as products of hybridised populations, including the skeleton of a child found at Lagar Velho in Portugal and the Peștera Muierii skeletons from Romania.

Genetic evidence

In 2010, geneticists announced that interbreeding had likely taken place, a result confirmed in 2012. The genomes of all non-Africans include portions that are of Neanderthal origin, a share estimated in 2014 to 1.5–2.1%. This DNA is absent in Sub-Saharan Africans (Yoruba people and San subjects). Ötzi the iceman, Europe's oldest preserved mummy, was found to possess an even higher percentage of Neanderthal ancestry.

The two percent of Neanderthal DNA in Europeans and Asians is not the

same in all Europeans and Asians: in all, approximately 20% of the

Neanderthal genome appears to survive in the modern human gene pool.

Genomic studies suggest that modern humans mated with at least two groups of archaic humans: Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Some researchers suggest admixture of 3.4–7.9% in modern humans of

non-African ancestry, rejecting the hypothesis of ancestral population

structure.

Detractors have argued and continue to argue that the signal of

Neanderthal interbreeding may be due to ancient African substructure,

meaning that the similarity is only a remnant of a common ancestor of

both Neanderthals and modern humans and not the result of interbreeding. John D. Hawks

has argued that the genetic similarity to Neanderthals may indeed be

the result of both structure and interbreeding, as opposed to just one

or the other.

An approximately 40,000 year old anatomically-modern human skeleton from Peștera cu Oase,

Romania, was found in 2015 to have a much larger proportion of DNA

matching the Neanderthal genome than seen in humans of today, and this

was estimated to have resulted from an interbreeding event as few as

four generations earlier. However, this hybrid Romania population does

not appear to have made a substantial contribution to the genomes of

later Europeans.

While some modern human nuclear DNA has been linked to the extinct Neanderthals, no mitochondrial DNA of Neanderthal origin has been detected, which in primates is almost always maternally transmitted.

This observation has prompted the hypothesis that whereas female humans

interbreeding with male Neanderthals were able to generate fertile

offspring, the progeny of female Neanderthals who mated with male humans

were either rare, absent or sterile.

However, Eastern Neanderthals derive significant portions of

their ancestry from an earlier dispersal of modern humans unrelated to

the one that gave rise to Eurasians today.

It is estimated that they split off shortly after the Khoisan

divergence some 200 kya. Such unidirectional flow is significant given

the current scenario of no Eurasian admixture in Western European

Neanderthals. This is not contradictory to the Out-of-Africa model,

which claims a single-dispersal to give rise to all Eurasians today. A

signal of an early dispersal is present in the genome of New Guineans,

who derive up to 2% of their ancestry from this group that apparently

diverged from other Africans 120 kya.

However, it is noted that the Denisovans do not carry this early human

dispersal signal. Pagani et al. therefore argue that the admixture

between this early modern human group, modern Eurasians, and

Neanderthals took place in Southern Arabia or the Levant and that the

latter group consisted of migrants from the Middle East into Siberia.

Interbreeding with Denisovans

Sequencing of the genome of a Denisovan, a distinct but related

archaic hominin, from the Denisova cave in the Siberian Altai region has

shown that 17% of its genome represents Neanderthal DNA.

Unsurprisingly, the genome from a 120,000 year old Neanderthal bone

found in the same cave more closely resembled the Neanderthal DNA

present in the Denisovan genome than that of Neanderthals from the Vindija cave in Croatia or the Mezmaiskaya cave in the Caucasus, suggesting that the gene flow came from a local interbreeding. However, the complete genome sequencing of DNA from a 90,000 year old bone fragment, Denisova 11,

showed it to have belonged to a Denisovan-Neanderthal hybrid, whose

father was a typical Denisovan with the Altai Neanderthal component

dating to an interbreeding more than 300 generations earlier, but the

specimen's mother was a Neanderthal belonging to a population more

closely related to the Vindija Neanderthal than to the sequenced Altai

Neanderthal genome. This suggests mobility or turnover among the

distinct Neanderthal populations.

Extinction

According to a 2014 study by Thomas Higham and colleagues of organic samples from European sites, Neanderthals died out in Europe between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago.

New dating in Iberia, where Neanderthal dates as late as 24,000 years

had been reported before, now suggests evidence of Neanderthal survival

in the peninsula after 42,000 years ago is almost non-existent.

Anatomically modern humans arrived in Mediterranean Europe

between 45,000 and 43,000 years ago, so the two different human

populations shared Europe for several thousand years. The exact nature of biological and cultural interaction between Neanderthals and other human groups is contested.

Possible scenarios for the extinction of the Neanderthals are:

- Neanderthals were a separate species from modern humans, and became extinct (because of climate change or interaction with modern humans) and were replaced by modern humans moving into their habitat between 45,000 and 40,000 years ago. Jared Diamond has suggested a scenario of violent conflict and displacement.

- Neanderthals were a contemporary subspecies that bred with modern humans and disappeared through absorption (interbreeding theory).

- Volcanic catastrophe: see Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption

mtDNA-based simulation of modern human expansion in Europe starting 1,600 generations ago. Neanderthal range in light grey

Climate change

About 55,000 years ago, the climate began to fluctuate wildly from

extreme cold conditions to mild cold and back in a matter of decades.

Neanderthal bodies were well-suited for survival in a cold climate—their

stocky chests and limbs stored body heat better than the Cro-Magnons.

Neanderthals died out in Europe between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago,

coinciding with the start of a very cold period.

Raw material sourcing and the examination of faunal remains found in the southern Caucasus

suggest that modern humans may have had a survival advantage, being

able to use social networks to acquire resources from a greater area. In

both the Late Middle Palaeolithic and Early Upper Palaeolithic more

than 95% of stone artifacts were drawn from local material, suggesting

Neanderthals restricted themselves to more local sources.

Coexistence with modern humans

Skeleton and restoration model of the La Ferrassie 1 Neanderthal man (National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo, 2013 photograph)

In November 2011 tests conducted at the Oxford Radiocarbon

Accelerator Unit in England on what were previously thought to be

Neanderthal baby teeth, which had been unearthed in 1964 from the Grotta

del Cavallo in Italy, were identified as the oldest modern human

remains discovered anywhere in Europe, dating from between 43,000 and

45,000 years ago.

Given that the 2014 study by Thomas Higham of Neanderthal bones and

tools indicates that Neanderthals died out in Europe between 41,000 and

39,000 years ago, the two different human populations shared Europe for

as long as 5,000 years.

Nonetheless, the exact nature of biological and cultural interaction

between Neanderthals and other human groups has been contested.

Modern humans co-existed with them in Europe starting around

45,000 years ago and perhaps even earlier. Neanderthals inhabited that

continent long before the arrival of modern humans. These modern humans

may have introduced a disease that contributed to the extinction of

Neanderthals, and that may be added to other recent explanations for

their extinction. When Neanderthal ancestors left Africa potentially as

early as over 800,000 years ago they adapted to the pathogens in their

European environment, unlike modern humans, who adapted to African

pathogens. This transcontinental movement is known as the Out of Africa model.

If contact between humans and Neanderthals occurred in Europe and Asia

the first contact may have been devastating to the Neanderthal

population, because they would have had little, if any, immunity to the

African pathogens. More recent historical events in Eurasia and the

Americas show a similar pattern, where the unintentional introduction of

viral or bacterial pathogens to unprepared populations has led to mass

mortality and local population extinction. The most well-known example of this is the arrival of Christopher Columbus

to the New World, which brought and introduced foreign diseases when he

and his crew arrived to a native population who had no immunity.

Anthropologist Pat Shipman, of Pennsylvania State University, suggested that domestication of the dog could have played a role in Neanderthals' extinction.

History of research

Neanderthal fossils were first discovered in 1829 in the Engis caves (the partial skull dubbed Engis 2), in what is now Belgium by Philippe-Charles Schmerling and the Gibraltar 1 skull in 1848 in the Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar. These finds were not, at the time,

recognized as representing an archaic form of humans.

The first discovery which was recognized as representing an archaic form of humans was made in August 1856, three years before Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published.

This was the discovery of the type specimen, Neanderthal 1, in a limestone quarry (Feldhofer Cave), located in Neandertal Valley in the German Rhineland, about 12 km (7 mi) east of Düsseldorf).

The find consisted of a skull cap, two femora, three bones of the right arm, two of the left arm, parts of the left ilium, fragments of a scapula,

and ribs. The workers who recovered the objects originally thought them

to be the remains of a cave bear. However, they eventually gave the

material to amateur naturalist Johann Carl Fuhlrott, who turned the fossils over to anatomist Hermann Schaaffhausen.

To date, the bones of over 400 Neanderthals have been found.

- 1829: A damaged skull of a Neanderthal child, Engis 2, is discovered in Engis, Netherlands (now Belgium).

- 1848: A female Neanderthal skull, Gibraltar 1, is found in Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar, but its importance is not recognised.

- 1856: Limestone miners discover the Neanderthal-type specimen, Neanderthal 1, in Neandertal, western Prussia (now Germany).

- 1864: William King is the first to recognise Neanderthal 1 as belonging to a separate species, for which he gives the scientific name Homo neanderthalensis. He then changed his mind on placing it in the genus Homo, arguing that the upper skull was different enough to warrant a separate genus since, to him, it had likely been "incapable of moral and theistic conceptions."

- 1880: The mandible of a Neanderthal child is discovered in a secure context in Šipka cave, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now the Czech Republic), associated with cultural debris, including hearths, Mousterian tools, and bones of extinct animals.

- 1886: Two well-preserved Neanderthal skeletons are found at Spy, Belgium, making the hypothesis that Neanderthal 1 was only a diseased modern human difficult to sustain.

- 1899: Sand excavation workers find hundreds of fragmentary Neanderthal remains representing at least 12 and likely as much as 70 individuals on a hill in Krapina, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Croatia).

- 1908: A very well preserved Neanderthal, La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1, is found in its eponymous site in France, said by the excavators to be a burial, a claim still heatedly contested. For historical reasons it remains the most famous Neanderthal skeleton.

- 1912: Marcellin Boule publishes his now discredited influential study of Neanderthal skeletal morphology based on La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1.

- 1953–1957: Ten Neanderthal skeletons are excavated in Shanidar Cave, Iraqi Kurdistan, by Ralph Solecki and colleagues.

- 1975: Erik Trinkaus's study of Neanderthal feet strongly argues that Neanderthals walked like modern humans.

- 1981: The site of Bontnewydd, Wales yielded an early Neanderthal tooth, the most north-western Neanderthal remain ever.

- 1987: Israeli Neanderthal Kebara 2 is dated (by TL and ESR) to 60,000 BP, thus later than the Israeli anatomically modern humans dated to 90,000 and 80,000 BP at Qafzeh and Skhul.

- 1997: Matthias Krings et al. are the first to amplify Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) using a specimen from Feldhofer grotto in the Neander valley.

- 2005: The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and associated institutions launch the Neanderthal genome project to sequence the Neanderthal nuclear genome.

- 2010: Discovery of Neanderthal admixture in the genome of modern populations.

- 2014: A comprehensive dating of Neanderthal bones and tools from hundreds of sites in Europe dates the disappearance of Neanderthals to 41,000 and 39,000 years ago.

- 2018: Report on the complete genomic sequence of Denisova 11, a first generation of Neanderthal-Denisovan hybrid.

Specimens

Notable European Neanderthals

Remains of more than 300 European Neanderthals have been found.- Neanderthal 1: The first human bones recognised as showing a non-modern anatomy. Discovered in 1856 in a limestone quarry at the Feldhofer grotto in Neanderthal, Germany, they consist of a skull cap, the two femora, the three right arm bones, two left arm bones, the ilium, and fragments of a scapula and ribs.

- La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1: Called the Old Man, a fossilised skull discovered in La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France, by A. and J. Bouyssonie, and L. Bardon in 1908. Characteristics include a low vaulted cranium and large browridge typical of Neanderthals. Estimated to be about 60,000 years old, the specimen was severely arthritic and had lost all his teeth long before death, leading some to suggest he was cared for by others.

- La Ferrassie 1: A fossilised skull discovered in La Ferrassie, France, by R. Capitan in 1909. It is estimated to be 70,000 years old. Its characteristics include a large occipital bun, low-vaulted cranium and heavily worn teeth.

- Le Moustier 1: One of the rare nearly complete Neanderthal skeletons to be discovered, it was excavated by a German team in 1908, at Peyzac-le-Moustier, France. Sold to a Berlin museum, the post cranial skeleton was bombed and mostly destroyed in 1945, and parts of the mid face were lost sometime after then. The skull, estimated to be less than 45,000 years old, includes a large nasal cavity and a less developed brow ridge and occipital bun than seen in other Neanderthals. The Mousterian tool techno-complex is named after its discovery site.

Notable Southwest Asian Neanderthals

Remains of more than 70 Southwest Asian Neanderthals have been found.

- Shanidar 1 to 10: Eight Neanderthals and two pre-Neanderthals (Shanidar 2 and 4) were discovered in the Zagros Mountains in Iraqi Kurdistan. One of the skeletons, Shanidar 4, was once thought to have been buried with flowers, a theory no longer accepted. To Paul B. Pettitt the "deliberate placement of flowers has now been convincingly eliminated", since "[a] recent examination of the microfauna from the strata into which the grave was cut suggests that the pollen was deposited by the burrowing rodent Meriones tersicus, which is common in the Shanidar microfauna and whose burrowing activity can be observed today".

- Amud 1: A male adult Neanderthal, dated to roughly 55,000 BP, and one of several found in a cave at Nahal Amud, Israel. At 178 cm (70 in), it is the tallest known Neanderthal. It also has the largest cranial capacity of all extinct hominins: 1,736 cm3.

- Kebara 2: A male adult post-cranial skeleton, dated to roughly 60,000 BP, that was discovered in 1983 in Kebara Cave, Israel. It has been studied extensively, for its hyoid, ribcage, and pelvis are much better preserved than in all other Neanderthal specimens.

Notable Central Asian Neanderthal

- Teshik-Tash 1: An 8–11-year-old skeleton discovered in Uzbekistan by Okladnikov in 1938. This is the only fairly complete skeleton discovered to the east of Iraq. Okladnikov claimed it was a deliberate burial, but this is debated.

Chronology

This section describes bones with Neanderthal traits in chronological order.

Mixed with H. heidelbergensis traits

- older than 350 ka: Sima de los Huesos c. 500:350 ka ago

- 350–200 ka: Pontnewydd 225 ka ago.

- 200–135 ka: Atapuerca, Vértesszőlős, Ehringsdorf, Casal de'Pazzi, Biache, La Chaise, Montmaurin, Prince, Lazaret, Fontéchevade

H. neanderthalensis fossils

- 130–50 ka: Krapina, Saccopastore skulls, Malarnaud, Altamura, Gánovce, Denisova, Okladnikov, Pech de l'Azé, Tabun 120–100±5 ka, Shanidar 1 to 9 80–60 ka, La Ferrassie 1 70 ka, Kebara 60 ka, Régourdou, Mt. Circeo, Combe Grenal, Erd 50 ka, La Chapelle-aux Saints 1 60 ka, Amud I 53±8 ka, Teshik-Tash.

- In radiocarbon range, > 50 ka: Le Moustier, Feldhofer, La Quina, l'Hortus, Kulna, Šipka, Saint Césaire, Bacho Kiro, El Castillo, Bañolas, El Sidrón (48±3 cal ka), Arcy-sur-Cure, Châtelperron, Figueira Brava, Mezmaiskaya (41±1 cal ka), Zafarraya, Vindija, Velika Pećina.

H. s. sapiens with traits reminiscent of Neanderthals

- younger than 35 Peștera cu Oase 37-42 ka, Mladeč 31 ka, Pestera Muierii 30 ka (n/s), Lagar Velho 1 24.5 ka.

In popular culture

Neanderthals have been portrayed in popular culture including

appearances in literature, visual media and comedy. Early 20th century

artistic interpretations often presented Neanderthals as beastly

creatures, emphasising hairiness and a rough, dark complexion.