| |

| Abbreviation | HRC |

|---|---|

| Motto | "Working for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Equal Rights" |

| Formation | 1980 |

| Founder | Steve Endean |

| Type | Nonprofit advocacy organization |

| Purpose | LGBTQ rights |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

President

| Chad Griffin |

| Affiliations | Human Rights Campaign Foundation, Human Rights Campaign PAC |

Revenue (2018)

| $45,636,641 |

| Expenses (2018) | $43,167,397 |

| Website | www |

The Human Rights Campaign (HRC) is the largest LGBTQ civil rights advocacy group and political lobbying organization in the United States. The organization focuses on protecting and expanding rights for LGBTQ individuals, most notably advocating for marriage equality, anti-discrimination and hate crimes legislation, and HIV/AIDS advocacy. The organization has a number of legislative initiatives as well as supporting resources for LGBTQ individuals.

Structure

HRC is an umbrella group of two separate non-profit organizations and a political action committee: the HRC Foundation, a 501(c)(3) organization that focuses on research, advocacy and education; the Human Rights Campaign, a 501(c)(4) organization that focuses on promoting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer

(LGBTQ) rights through lobbying Congress and state and local officials

for support of pro-LGBTQ bills, and mobilizing grassroots action amongst

its members; and the HRC Political Action Committee, a super PAC which supports and opposes political candidates.

Leadership

The Human Rights Campaign's leadership includes President Chad Griffin.

HRC's work is supported by three boards: the Board of Directors, which

is the governing body for the organization; the HRC Foundation Board,

which manages the foundation's finances and establishes official

policies governing the foundation; and the Board of Governors, which

manages the organization's local outreach nationwide.

History

Human Rights Campaign headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Steve Endean, who had worked with a previously established Gay Rights National Lobby from 1978, established the Human Rights Campaign Fund political action committee in 1980. The two groups eventually merged. In 1983, Vic Basile,

at the time one of the leading LGBT rights activists in Washington,

D.C., was elected as the first executive director. In October 1986, the

HRC Foundation (HRCF) was formed as a non-profit organization.

In January 1989, Basile announced his departure, and HRC

reorganized from serving mainly as a political action committee (PAC) to

broadening its function to encompass lobbying, research, education, and

media outreach.

HRC decided on a new Statement of Purpose: "For the promotion of the

social welfare of the gay and lesbian community by drafting, supporting

and influencing legislation and policy at the federal, state and local

level." Tim McFeeley, a Harvard Law School graduate, founder of the Boston Lesbian and Gay Political Alliance, and a co-chair of the New England HRC Committee, was elected the new executive director. Total membership was then approximately 25,000 members.

In 1992, HRC endorsed a presidential candidate for the first time, Bill Clinton. In March 1993, HRC began a new project, National Coming Out Day. From January 1995 until January 2004, Elizabeth Birch

served as the executive director of the HRC. Under her leadership, the

institution more than quadrupled its membership to 500,000 members.

In 1995, the organization dropped the word "Fund" from its name,

becoming the Human Rights Campaign. That same year, it underwent a

complete reorganization. The HRC Foundation added new programs such as

the Workplace Project and the Family Project, while HRC itself broadly

expanded its research, communications, and marketing/public relations

functions. The organization also unveiled a new logo, a yellow equal sign inside of a blue square.

The Human Rights Campaign often has a large presence at LGBT-related events such as the Chicago Pride Parade as seen above.

As part of the activities surrounding the Millennium March on Washington, the HRC Foundation sponsored a fundraising concert at Washington, D.C.'s RFK Stadium

on April 29, 2000. Billed as a concert to end hate crimes, "Equality

Rocks" honored hate crime victims and their families, such as featured

speakers Dennis and Judy Shepard, the parents of Matthew Shepard. The event included Melissa Etheridge, Garth Brooks, Pet Shop Boys, k.d. lang, Nathan Lane, Rufus Wainwright, Albita Rodríguez, and Chaka Khan.

Elizabeth Birch's successor, Cheryl Jacques,

resigned in November 2004 after only 11 months as executive director.

Jacques said she had resigned over "a difference in management

philosophy".

In March 2005, HRC announced the appointment of Joe Solmonese

as the president. He served in that position until stepping down in May

2012 to co-chair the Barack Obama presidential campaign.

HRC launched its Religion and Faith Program in 2005 to mobilize

clergy to advocate for LGBT people, and helped form DC Clergy United for

Marriage Equality, which was involved in the legalization of same-sex marriage in the District of Columbia. On March 10, 2010, the first legally recognized same-sex weddings in the District of Columbia were held at the headquarters of the Human Rights Campaign.

On August 9, 2007, HRC and Logo TV co-hosted a forum for 2008 Democratic presidential candidates dedicated specifically to LGBT issues.

In 2010, HRC lobbied for the repeal of the United States' ban on HIV-positive people's entry into the country for travel or immigration.

In September 2011, it was announced that Joe Solmonese would step

down as president of HRC following the end of his contract in 2012. Despite initial speculation that former Atlanta City Council president Cathy Woolard would be appointed, no replacement was announced until March 2, 2012, when American Foundation for Equal Rights co-founder Chad Griffin was announced as Solmonese's successor. Griffin took office on June 11, 2012.

In 2012, HRC said that it had raised and contributed $20 million to re-elect President Obama and to advance same-sex marriage.

In addition to the Obama re-election campaign, HRC spent money on

marriage-related ballot measures in Washington, Maine, Maryland and

Minnesota, and the election of Democratic Senator Tammy Baldwin in Wisconsin.

In 2013, HRC conducted a postcard campaign in support of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA).

In 2019, HRC joined with 42 other religious and allied organizations in issuing a statement opposing Project Blitz, an effort by a coalition of Christian right organizations to influence state legislation.

Executive Directors

| Years | Name |

|---|---|

| 1980–1983 | Steve Endean |

| 1983–1989 | Vic Basile |

| 1989–1995 | Tim McFeeley |

| 1995–2004 | Elizabeth Birch |

| 2004–2004 | Cheryl Jacques |

| 2005–2012 | Joe Solmonese |

| 2012–present | Chad Griffin |

Annual fundraisers

Each

year since 1997, HRC has hosted a national dinner that serves as the

organization's single largest annual fundraiser. In 2009, President Barack Obama

spoke at HRC's 13th Annual National Dinner. In his speech, President

Obama reaffirmed his pledge to repeal "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" and the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), as well as his commitment to passing the Employment Non-Discrimination Act.

He gave the keynote speech in 2011 as well, reiterating his pledge to

fight for DOMA repeal and for the passage of ENDA, and to combat

bullying of LGBT youth. Other featured speakers at past dinners have

included Bill Clinton, Maya Angelou, Kweisi Mfume, Joseph Lieberman, Hillary Clinton, Richard Gephardt, John Lewis, Rosie O'Donnell, Nancy Pelosi, Tim Gunn, Suze Orman, Sally Field, Cory Booker, Tammy Baldwin, and Betty DeGeneres.

HRC historical records

The historical records of the Human Rights Campaign are maintained in a collection at the Cornell University Library. Arriving at Cornell in 2004, the records include strategic planning documents, faxes, minutes, e-mails, press releases, posters, and campaign buttons. Taking up 84 cubic feet (2.4 m3),

the archive is the second largest in the library's Division of Rare and

Manuscript Collections, Human Sexuality Collection. In February 2007,

the archive was opened to scholars at the library, and selected records

were organized into an online exhibit called "25 Years of Political

Influence: The Records of the Human Rights Campaign".

Programs

According

to the organization, the Human Rights Campaign "is organized for the

charitable and educational purposes of promoting public education and

welfare for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community."

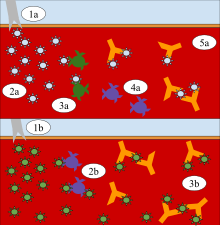

The HRC Foundation provides resources on coming out, transgender issues, LGBT-related healthcare topics, and information about workplace issues faced by LGBT people, including the Corporate Equality Index.

HRC has lobbied for the passage of anti-discrimination and hate crime laws. The organization supported the passage of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which expanded federal hate-crime law to allow the Justice Department to investigate and prosecute crimes motivated by a victim's actual or perceived gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability.

The organization's work on health issues traditionally focused on

responding to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In recent years, HRC has addressed

discrimination in health care settings for LGBT employees, patients and

their families. Since 2007, the Human Rights Campaign Foundation has

published the "Healthcare Equality Index", which rates hospitals on

issues such as patient and employee non-discrimination policies,

employee cultural competency training, and hospital visitation rights for LGBT patients' families.

Lobbyists from the Human Rights Campaign worked with the Obama administration to extend hospital visitation rights to same-sex partners. HRC lobbied extensively for the repeal of the Don't Ask Don't Tell (DADT) law, which barred gay and lesbian people from serving openly in the United States military.

Logo

The official logo of the HRC, adopted in 1995, consists of a yellow equals sign imposed onto a blue background. The logo was created in 1995 by design firm Stone Yamashita. The previous logo used by the HRC (then known as the HRCF) featured a stylized flaming torch. HRC uses the term Equality Flag for flags bearing their logo.

Same-sex marriage logo

The HRC equal sign logo reworked in red and pink to show particular support for same-sex marriage.

HRC shared a red version of its logo – selected by marketing director

Anastasia Khoo because the color is synonymous with love – on social network services

on March 25, 2013, and asked its supporters to do the same to show

support for same-sex marriage in light of two cases that were before the

U.S. Supreme Court (United States v. Windsor and Hollingsworth v. Perry). The logo went viral, and Facebook saw a 120% increase in the number of profile photo changes on March 26. Celebrities such as George Takei, Beyonce, Sophia Bush, Padma Lakshmi, Martha Stewart, Macklemore, Ryan Lewis and Ellen DeGeneres shared the logo with their millions of followers on social network services and politicians like Senator Claire McCaskill (D-MO), Jay Rockefeller (D-WV), and Kay Hagan (D-NC) did the same.

Brands and corporations showed their support for same-sex marriage with creative recreations of the red HRC logo. Supporters included Bud Light, Bonobos, Fab.com, Kenneth Cole, L'Occitane en Provence, Maybelline, Absolut, Marc Jacobs International, Smirnoff, Martha Stewart Weddings, and HBO's True Blood.

Major print and online news sources reported on the success of the viral campaign, including MSNBC, Time, Mashable, and The Wall Street Journal.

Controversies

Critics

have taken HRC to task for its working environment. In the fall of

2014, HRC commissioned outside consultants to conduct a series of focus

groups and surveys with the organization's staff. In the report, which

was obtained by BuzzFeed,

staff of the organization described the working environment at HRC as

"judgmental", "exclusionary", "sexist", and "homogenous". The report

stated that "Leadership culture is experienced as homogenous — gay,

white, male." Acknowledging the report, HRC president Chad Griffin said:

"Like many organizations and companies throughout our country, HRC has

embarked on a thoughtful and comprehensive diversity and inclusion

effort with the goals of better representing the communities we serve." In August 2015, Pride at Work, an LGBT affiliate of the AFL–CIO,

approved a resolution that calls on member organizations to stop

funding HRC until the group addresses what Pride at Work sees as

problems with HRC's Corporate Equality Index.

HRC has been accused of overstating the number of its actual members in order to appear more influential in politics.

Former HRC President Joe Solmonese responded, saying that "[m]embership

is about more than contributions ... [i]t's about sending e-mails to

elected officials, volunteering time or lobbying members of Congress"

and more than half of its members made contributions during the previous

two years. Earlier, HRC spokesperson Steven Fisher stated that its membership includes anyone who has donated at least $1.

HRC has also been criticized for exceedingly generous executive salaries.

Some transgender people have criticized the HRC for its stance on the 2007 version of ENDA, which at the time included sexual orientation as a protected category but not gender identity and expression. Once the legislation was submitted by Rep. Barney Frank, HRC officially neither opposed nor supported it. This followed a speech by former HRC President Joe Solmonese at the transgender Southern Comfort Conference the previous month, where he said that HRC "oppose[d] any legislation that is not absolutely inclusive".

HRC later explained that it could not actively support a non-inclusive

bill, but did not oppose it because the legislation would strategically

advance long-term efforts to pass a trans-inclusive ENDA. However, in a letter to U.S. Representatives,

HRC did express support for the bill, stating that while HRC is

"greatly disappointed that the current version of ENDA is not

fully-inclusive ... we appreciate the steadfast efforts of our ...

allies ... even when they are forced ... to make progress that is

measured by inches rather than yards."

Endorsement of Republican candidates

Critics of the HRC have accused the organization of favoring the Democratic Party. Andrew Sullivan, a gay political columnist and blogger, has been critical of the HRC, calling it "a patronage wing of the Democratic party."

It has received backlash and criticism for several nominations of

Republicans, when their Democratic opponents scored higher on HRC's own

index.

HRC was criticized for its endorsement of New York Republican Al D'Amato in his 1998 campaign for re-election to the U.S. Senate. HRC defended the endorsement because of D'Amato's support for the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) and the repeal of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell". However, many liberal LGBT leaders objected to D'Amato's conservative stances, including his opposition to affirmative action and abortion, and felt that HRC should have taken those positions into account when deciding on the endorsement.

In 2014, long-time supporter of same-sex marriage Shenna Bellows was nominated for a U.S. Senate seat in Maine. HRC endorsed her opponent, incumbent Republican Senator Susan Collins,

who had previously lacked a history of supporting marriage equality

initiatives. However, Collins later clarified her view in support of

LGBT marriage equality.

On March 11, 2016, HRC voted to endorse Republican US Senator Mark Kirk over his Democratic Party challenger Representative Tammy Duckworth in his re-election bid to the US Senate.

Though Kirk later announced his support for same-sex marriage, the

endorsement was met with widespread surprise and criticism in news media

and social media as HRC had given Kirk a score of 78 percent out of 100

percent on LGBT issues, while it had awarded Duckworth a score of 100

percent. David Nir at Daily Kos called the endorsement as "appalling as it is embarrassing" and "pathetic and stupid", while Slate observed that Democratic control of the Senate was effectively necessary for passing the Equality Act of 2015

and beneficial for many other LGBT equality issues, and thus it would

be in line with the organization's stated goals for Duckworth to be

elected rather than Kirk. Meanwhile, The New Republic

stated that, in light of a recent internal report revealing HRC's

"serious diversity problem", "Choosing the white male candidate in this

race over the Asian-American female candidate—someone who happens to

have a better voting record anyway—is probably the worst way of

convincing your detractors that you are taking a core problem

seriously." HRC president Chad Griffin defended the endorsement in a column published by the Independent Journal Review,

describing the senator's work on behalf of LGBT equality issues,

including co-sponsoring the Equality Act of 2015. Griffin stated: "The

truth is we need more cross party cooperation on issues of equality, not

less", adding "when members of Congress vote the right way and stand up

for equality — regardless of party — we must stand with them. We simply

cannot ask members of Congress to vote with us, and then turn around

and try to kick them out of office."

On October 28, 2016, on the day following Mark Kirk's controversial

debate comment on Tammy Duckworth's heritage, HRC explicitly stated

their endorsement of Kirk "remains unchanged" while asking him to

"rescind" his comment. Slate stated this proved HRC's "worst critics right" and that HRC "is simply irredeemable". On October 29, two days after the comment, HRC described Kirk's statement as "deeply offensive and racist," revoked its endorsement of Kirk, and instead endorsed Duckworth for the U.S. Senate.

2016 United States presidential endorsement

On January 19, 2016, the Human Rights Campaign's 32-person Board of Directors voted to endorse Hillary Clinton for president. This resulted in considerable controversy, causing thousands of users on HRC's Facebook page to post comments critical of the decision. Many cited HRC's own "congressional scorecard" (which records a 100% rating for her rival for the Democratic nomination, Bernie Sanders, while Clinton herself only scores 89%) as inconsistent with their endorsement.

Additional scrutiny was also placed upon the connections Clinton

herself has to the organization when it was revealed that HRC's

President, Chad Griffin, had previously been employed by Clinton's husband, former US President Bill Clinton.

2018 New York gubernatorial election endorsement

On January 31, 2018, the Human Rights Campaign endorsed incumbent governor Andrew Cuomo. However, Cynthia Nixon, who is bisexual, announced that she was running on March 25, 2018.

Despite this, HRC still supported Cuomo. In response, HRC received

criticism for not supporting an LGBTQ+ candidate, and supporting her

opponent instead. Jimmy Van Bramer,

a gay New York City Council Member who endorsed Nixon, said, "The HRC

endorsement hurts Cynthia Nixon's chances," and that "coming out against

a viable progressive queer woman is the wrong thing to do."