From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Zen | |

| Chinese name | |

|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 禪 |

| Simplified Chinese | 禅 |

| Vietnamese name | |

|---|---|

| Vietnamese | Thiền |

| Hán-Nôm | 禪 |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 선 |

| Hanja | 禪 |

| Japanese name | |

|---|---|

| Kanji | 禅 |

| Sanskrit name | |

|---|---|

| Sanskrit | ध्यान (dhyāna) |

Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China during the Tang dynasty as the Chan school (Chánzong) of Chinese Buddhism and later developed into various schools. Chán Buddhism was also influenced by Taoist philosophy, especially Neo-Daoist thought. From China, Chán spread south to Vietnam and became Vietnamese Thiền, northeast to Korea to become Seon Buddhism, and east to Japan, becoming Japanese Zen.

The term Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (Chán), which traces its roots to the Indian practice of dhyāna ("meditation"). Zen emphasizes rigorous self-control, meditation-practice, insight into the nature of things (Ch. jianxing, Jp. kensho, "perceiving the true nature"), and the personal expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of sutras and doctrine and favors direct understanding through spiritual practice and interaction with an accomplished teacher.

The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahayana thought, especially Yogachara, the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras and the Huayan school, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, and the Bodhisattva-ideal. The Prajñāpāramitā literature as well as Madhyamaka thought have also been influential in the shaping of the apophatic and sometimes iconoclastic nature of Zen rhetoric.

Etymology

The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna (ध्यान ), which can be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative state".

The actual Chinese term for the "Zen school" is Chánzong, while "Chan" just refers to the practice of meditation itself (xichan) or the study of meditation (chanxue) though it is often used as an abbreviated form of Chánzong.

Practice

Meditation

The practice of dhyana or meditation, especially sitting meditation (Ch. zuòchán, Jp. zazen) is a central part of Zen Buddhism.

The practice of Buddhist meditation first entered China through the translations of An Shigao (fl. c. 148–180 CE), and Kumārajīva (334–413 CE), who both translated Dhyāna sutras, which were influential early meditation texts mostly based on the Yogacara (yoga praxis) teachings of the Kashmiri Sarvāstivāda circa 1st–4th centuries CE. Among the most influential early Chinese meditation texts include the Anban Shouyi Jing (Sutra on ānāpānasmṛti), the Zuochan Sanmei Jing (Sutra of sitting dhyāna samādhi) and the Damoduolo Chan Jing (Dharmatrata dhyāna sutra).

While dhyāna in a strict sense refers to the four dhyānas, in Chinese Buddhism, dhyāna may refer to various kinds of meditation techniques and their preparatory practices, which are necessary to practice dhyāna. The five main types of meditation in the Dhyāna sutras are ānāpānasmṛti (mindfulness of breathing); paṭikūlamanasikāra meditation (mindfulness of the impurities of the body); maitrī meditation (loving-kindness); the contemplation on the twelve links of pratītyasamutpāda; and contemplation on the Buddha. According to the modern Chan master Sheng Yen,

these practices are termed the "five methods for stilling or pacifying

the mind" and serve to focus and purify the mind, and can lead to the dhyana absorptions. Chan also shares the practice of the four foundations of mindfulness and the Three Gates of Liberation (śūnyatā, signlessness or animitta and wishlessness or apraṇihita) with early Buddhism and classic Mahayana.

Early Chan texts also teach forms of meditation that are unique to Mahayana Buddhism, for example, the Treatise on the Essentials of Cultivating the Mind which depicts the teachings of the 7th-century East Mountain school teaches a visualization of a sun disk, similar to that taught in the Sutra of the Contemplation of the Buddha Amitáyus.

Later Chinese Buddhists developed their own meditation manuals and texts, one of the most influential being the works of the Tiantai patriarch, Zhiyi.

His works seemed to have exerted some influence on the earliest

meditation manuals of the Chán school proper, an early work being the

widely imitated and influential Tso-chan-i (Principles of sitting meditation, c. 11th century).

Common meditation forms

Mindfulness of breathing

The 'meditation hall' (Jp. zendō, Ch. chántáng) of Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-Ji

During sitting meditation (坐禅, Ch. zuòchán, Jp. zazen, Ko. jwaseon), practitioners usually assume a position such as the lotus position, half-lotus, Burmese, or seiza, often using the dhyāna mudrā. Often, a square or round cushion placed on a padded mat is used to sit on; in some other cases, a chair may be used.

To regulate the mind, Zen students are often directed towards

counting breaths. Either both exhalations and inhalations are counted,

or one of them only. The count can be up to ten, and then this process

is repeated until the mind is calmed. Zen teachers like Omori Sogen teach a series of long and deep exhalations and inhalations as a way to prepare for regular breath meditation. Attention is usually placed on the energy center (dantian) below the navel. Zen teachers often promote diaphragmatic breathing, stating that the breath must come from the lower abdomen (known as hara or tanden in Japanese), and that this part of the body should expand forward slightly as one breathes. Over time the breathing should become smoother, deeper and slower.

When the counting becomes an encumbrance, the practice of simply

following the natural rhythm of breathing with concentrated attention is

recommended.

Silent Illumination and Just Sitting

Another common form of sitting meditation is called "Silent illumination" (Ch. mòzhào, Jp. mokushō). This practice was traditionally promoted by the Caodong school of Chinese Chan and is associated with Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091—1157) who wrote various works on the practice. This method derives from the Indian Buddhist practice of the union (Skt. yuganaddha) of śamatha and vipaśyanā.

In Hongzhi's practice of "nondual objectless meditation" the

mediator strives to be aware of the totality of phenomena instead of

focusing on a single object, without any interference, conceptualizing, grasping, goal seeking, or subject-object duality.

This practice is also popular in the major schools of Japanese Zen, but especially Sōtō, where it is more widely known as Shikantaza (Ch. zhǐguǎn dǎzuò, "Just sitting").

Considerable textual, philosophical, and phenomenological justification

of the practice can be found throughout the work of the Japanese Sōtō Zen thinker Dōgen, especially in his Shōbōgenzō, for example in the "Principles of Zazen" and the "Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen". While the Japanese and the Chinese forms are similar, they are distinct approaches.

Hua Tou and Kōan contemplation

Calligraphy of "Mu" (Hanyu Pinyin: wú) by Torei Enji. It figures in the famous Zhaozhou's dog kōan

During the Tang dynasty, gōng'àn (Jp. kōan)

literature became popular. Literally meaning "public case", they were

stories or dialogues, describing teachings and interactions between Zen masters

and their students. These anecdotes give a demonstration of the

master's insight. Kōan are meant to illustrate the non-conceptual

insight (prajña) that the Buddhist teachings point to. During the Sòng dynasty, a new meditation method was popularized by figures such as Dahui, which was called kanhua chan ("observing the phrase" meditation) which referred to contemplation on a single word or phrase (called the huatou, "critical phrase") of a gōng'àn. In Chinese Chan and Korean Seon, this practice of "observing the huatou" (hwadu in Korean) is a widely practiced method. It was taught by the influential Seon master Chinul (1158–1210), and modern Chinese masters like Sheng Yen and Xuyun.

In the Japanese Rinzai school, kōan introspection developed its own formalized style, with a standardized curriculum of kōans which must be studies and "passed" in sequence. This process includes standardized "checking questions" (sassho) and common sets of "capping phrases" (jakugo) or poetry citations that are memorized by students as answers. The Zen student's mastery of a given kōan is presented to the teacher in a private interview (referred to in Japanese as dokusan, daisan, or sanzen).

While there is no unique answer to a kōan, practitioners are expected

to demonstrate their spiritual understanding through their responses.

The teacher may approve or disapprove of the answer and guide the

student in the right direction. The interaction with a teacher is

central in Zen, but makes Zen practice also vulnerable to

misunderstanding and exploitation. Kōan-inquiry may be practiced during zazen (sitting meditation), kinhin (walking meditation), and throughout all the activities of daily life. The goal of the practice is often termed kensho (seeing one's true nature).

Kōan practice is particularly emphasized in Rinzai, but it also occurs in other schools or branches of Zen depending on the teaching line.

Nianfo chan

Nianfo (Jp. nembutsu, from Skt. buddhānusmṛti "recollection of the Buddha") refers to the recitation of the Buddha's name, in most cases the Buddha Amitabha. In Chinese Chan, the Pure Land practice of nianfo based on the phrase Nāmó Āmítuófó (Homage to Amitabha) is a widely practiced form of Zen meditation. This practice was adopted from Pure land Buddhism and syncretized with Chan meditation by Chinese figures such as Yongming Yanshou, Zhongfen Mingben, and Tianru Weize. During the late Ming, the harmonization of Pure land practices with Chan meditation was continued by figures such as Yunqi Zhuhong and Hanshan Deqing.

This practice, as well as its adaptation into the "nembutsu kōan" was also used by the Japanese Ōbaku school of Zen.

Pointing to the nature of the mind

According

to Charles Luk, in the earliest traditions of Chán, there was no fixed

method or formula for teaching meditation, and all instructions were

simply heuristic methods, to point to the true nature of the mind, also

known as Buddha-nature. According to Luk, this method is referred to as the "Mind Dharma", and exemplified in the story (in the Flower Sermon) of Śākyamuni Buddha holding up a flower silently, and Mahākāśyapa smiling as he understood.

A traditional formula of this is, "Chán points directly to the human

mind, to enable people to see their true nature and become buddhas."

Bodhisattva virtues and vows

Victoria Zen Centre Jukai ceremony, January 2009.

Since Zen is a form of Mahayana Buddhism, it is grounded on the schema of the bodhisattva path which is based on the practice of the "transcendent virtues" or "perfections" (Skt. pāramitā, Ch. bōluómì, Jp. baramitsu) as well as the taking of the bodhisattva vows. The most widely used list of six virtues is: generosity, moral training (incl. five precepts), patient endurance, energy or effort, meditation (dhyana), wisdom. An important source for these teachings is the Avatamsaka sutra, which also outlines the grounds (bhumis) or levels of the bodhisattva path. The pāramitās are mentioned in early Chan works such as Bodhidharma's Two entrances and four practices and are seen as an important part of gradual cultivation (jianxiu) by later Chan figures like Zongmi.

An important element of this practice is the formal and ceremonial taking of refuge in the three jewels, bodhisattva vows and precepts. Various sets of precepts are taken in Zen including the five precepts, "ten essential precepts", and the sixteen bodhisattva precepts. This is commonly done in an initiation ritual (Ch. shòu jiè, Jp. Jukai, Ko. sugye, "receiving the precepts") which is also undertaken by lay followers and marks a layperson as a formal Buddhist.

The Chinese Buddhist practice of fasting (zhai), especially during the uposatha days (Ch. zhairi, "days of fasting") can also be an element of Chan training. Chan masters may go on extended absolute fasts, as exemplified by master Hsuan Hua's 35 day fast which he undertook during the Cuban missile crisis for the generation of merit.

The arts and physical culture

Hakuin Ekaku, 'Hotei in a Boat', Yale University Art Gallery.

The kare-sansui (dry landscape) zen garden at Ryōan-ji

Two grandmasters of the Shaolin Temple of Chinese Chan, Shi DeRu and Shi DeYang.

Certain arts such as painting, calligraphy, poetry, gardening, flower arrangement, tea ceremony and others have also been used as part of zen training and practice. Classical Chinese arts like brush painting and calligraphy were used by Chan monk painters such as Guanxiu and Muqi Fachang to communicate their spiritual understanding in unique ways to their students. Zen paintings are sometimes termed zenga in Japanese. Hakuin is one Japanese Zen master who was known to create a large corpus of unique sumi-e (ink and wash paintings) and Japanese calligraphy to communicate zen in a visual way. His work and that of his disciples were widely influential in Japanese Zen. Another example of Zen arts can be seen in the short lived Fuke sect of Japanese Zen which practiced a unique form of "blowing zen" (suizen) by playing the shakuhachi bamboo flute.

Traditional martial arts, like Japanese archery, other forms of Japanese budō and Chinese martial arts (gōngfu) have also been seen as forms of zen praxis. This tradition goes back to the influential Shaolin Monastery in Henan, which developed the first institutionalized form of gōngfu. By the late Ming, Shaolin gōngfu

was very popular and widespread, as evidenced by mentions in various

forms of Ming literature (featuring staff wielding fighting monks like Sun Wukong)

and historical sources which also speak of Shaolin's impressive

monastic army that rendered military service to the state in return for

patronage. These Shaolin practices,

which began to develop around the 12th century, were also traditionally

seen as a form of Chan Buddhist inner cultivation (today called wuchan, "martial chan"). The Shaolin arts also made use of Taoist physical exercises (taoyin) breathing and energy cultivation (qìgōng) practices. They were seen as therapeutic practices which improved "internal strength" (neili), health and longevity (lit. "nourishing life" yangsheng), as well as means to spiritual liberation.

The influence of these Taoist practices can be seen in the work of Wang

Zuyuan (ca. 1820–after 1882), a scholar and minor bureaucrat who

studied at Shaolin. Wang's Illustrated Exposition of Internal Techniques (Neigong tushuo) shows how Shaolin exercises were drawn from Taoist methods like those of the Yi jin jing and Eight pieces of brocade, possibly influenced by the Ming dynasty's spirit of religious syncretism. According to the modern Chan master Sheng Yen, Chinese Buddhism has adopted internal cultivation exercises from the Shaolin tradition

as ways to "harmonize the body and develop concentration in the midst

of activity." This is because, "techniques for harmonizing the vital energy are powerful assistants to the cultivation of samadhi and spiritual insight."

Korean Seon also has developed a similar form of active physical training, termed Sunmudo.

In Japan, the classic combat arts (budō) and zen practice have been in contact since the embrace of Rinzai Zen by the Hōjō clan in the 13th century, who applied zen discipline to their martial practice. One influential figure in this relationship was the Rinzai priest Takuan Sōhō who was well known for his writings on zen and budō addressed to the samurai class (especially his The Unfettered Mind). The Rinzai school also adopted certain Taoist energy practices. They were introduced by Hakuin

(1686–1769) who learned various techniques from a hermit named Hakuyu

who helped Hakuin cure his "Zen sickness" (a condition of physical and

mental exhaustion).

Intensive group practice

Intensive group meditation may be practiced occasionally in some temples. In the Japanese language, this practice is called sesshin.

While the daily routine may require monks to meditate for several hours

each day, during the intensive period they devote themselves almost

exclusively to zen practice. The numerous 30–50 minute long sitting

meditation (zazen) periods are interwoven with rest breaks, ritualized formal meals (Jp. oryoki), and short periods of work (Jp. samu) that are to be performed with the same state of mindfulness. In modern Buddhist practice in Japan, Taiwan,

and the West, lay students often attend these intensive practice

sessions or retreats. These are held at many Zen centers or temples.

Zen chanting and rituals

Chanting The Buddhist Scriptures, by Taiwanese painter Li Mei-shu.

Most Zen monasteries, temples and centers perform various rituals, services and ceremonies (such as initiation ceremonies and funerals) which are always accompanied by the chanting of verses, poems or sutras. There are also ceremonies which are specifically for the purpose of sutra recitation (Ch. niansong, Jp. nenju) itself. Zen schools may have an official sutra book which collects these writings (in Japanese, these are called kyohon). Practitioners may chant major Mahayana sutras such as the Heart Sutra and chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra (often called the "Avalokiteśvara Sutra"). Dhāraṇīs and Zen poems may also be part of a Zen temple liturgy, including texts like the Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi, the Sandokai, the Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī, and the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra.

The butsudan is the altar in a monastery, temple or a lay person's home, where offerings are made to the images of the Buddha, bodhisattvas and deceased family members and ancestors. Rituals usually center on major Buddhas or bodhisattvas like Avalokiteśvara (see Guanyin), Kṣitigarbha and Manjushri.

An important element in Zen ritual practice is the performance of ritual prostrations (Jp. raihai) or bows.

One popular form of ritual in Japanese Zen is Mizuko kuyō (Water child) ceremonies, which are performed for those who have had a miscarriage, stillbirth, or abortion. These ceremonies are also performed in American Zen Buddhism. A widely practiced ritual in Chinese Chan is variously called the "Rite for releasing the hungry ghosts" or the "Releasing flaming mouth". The ritual might date back to the Tang dynasty, and was very popular during the Ming and Qing dynasties, when Chinese Esoteric Buddhist practices became diffused throughout Chinese Buddhism. The Chinese holiday of the Ghost Festival

might also be celebrated with similar rituals for the dead. These ghost

rituals are a source of contention in modern Chinese Chan, and masters

such as Sheng Yen criticize the practice for not having "any basis in Buddhist teachings".

Another important type of ritual practiced in Zen are various repentance or confession rituals (Jp. zange)

which were widely practiced in all forms of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism.

One popular Chan text on this is known as the Emperor Liang Repentance

Ritual, composed by Chan master Baozhi. Dogen also wrote a treatise on repentance, the Shushogi. Other rituals could include rites dealing with local deities (kami in Japan), and ceremonies on Buddhist holidays such as Buddha's Birthday.

Funerals

are also an important ritual and are a common point of contact between

Zen monastics and the laity. Statistics published by the Sōtō school

state that 80 percent of Sōtō laymen visit their temple only for reasons

having to do with funerals and death. Seventeen percent visit for

spiritual reasons and 3 percent visit a Zen priest at a time of personal

trouble or crisis.

Esoteric practices

Depending on the tradition, esoteric methods such as mantra and dhāraṇī

are also used for different purposes including meditation practice,

protection from evil, invoking great compassion, invoking the power of

certain bodhisattvas, and are chanted during ceremonies and rituals. In the Kwan Um school of Zen for example, a mantra of Guanyin (“Kwanseum Bosal”) is used during sitting meditation. The Heart Sutra Mantra is also another mantra that is used in Zen during various rituals. Another example is the Mantra of Light (kōmyō shingon), which is common in Japanese Soto Zen and was derived from the Shingon sect.

The usage of esoteric mantras in Zen goes back to the Tang dynasty, and there is evidence that Chan Buddhists adopted practices from Esoteric Buddhism in findings from Dunhuang. According to Henrik Sørensen, several successors of Shenxiu (such as Jingxian and Yixing) were also students of the Zhenyan (Mantra) school. Influential esoteric dhāraṇī, such as the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra, also begin to be cited in the literature of the Baotang school during the Tang dynasty.

There is also documentation that monks living at Shaolin temple

during the eighth century performed esoteric practices there such as

mantra and dharani, and that these also influenced Korean Seon Buddhism. During the Joseon dynasty,

the Seon school was not only the dominant tradition in Korea, but it

was also highly inclusive and ecumenical in its doctrine and practices,

and this included Esoteric Buddhist lore and rituals (which appear in

Seon literature from the 15th century onwards). According to Sørensen,

the writings of several Seon masters (such as Hyujeong) reveal they were esoteric adepts.

In Japanese Zen, the use of esoteric practices within Zen is sometimes termed "mixed Zen" (kenshū zen 兼修禪), and the figure of Keizan Jōkin (1264–1325) is seen as introducing this into the Soto school. The Japanese founder of the Rinzai school, Myōan Eisai (1141–1215) was also a well known practitioner of esoteric Buddhism and wrote various works on the subject.

According to William Bodiford, a very common dhāraṇī in Japanese Zen is the Śūraṅgama spell (Ryōgon shu

楞嚴呪; T. 944A), which is repeatedly chanted during summer training

retreats as well as at "every important monastic ceremony throughout the

year" in Zen monasteries. Some Zen temples also perform esoteric rituals, such as the homa ritual which is performed at the Soto temple of Eigen-ji. As Bodiford writes "perhaps the most notable examples of this phenomenon is the ambrosia gate (kanro mon 甘露門) ritual performed at every Sōtō Zen temple", which is associated feeding hungry ghosts, ancestor memorial rites and the ghost festival. Bodiford also notes that formal Zen rituals of Dharma transmission often involve esoteric initiations

Doctrine

A Dharma talk by Seon nun Daehaeng Kun Sunim, Hanmaum Seon Center, South Korea.

Though Zen-narrative states that it is a "special transmission outside scriptures" which "did not stand upon words", Zen does have a rich doctrinal background, which is firmly grounded in the Buddhist tradition. It was thoroughly influenced by Mahayana teachings on the bodhisattva path, Chinese Madhyamaka (Sānlùn), Yogacara (Wéishí), Prajñaparamita, the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, and other Buddha nature texts. The influence of Madhyamaka and Prajñaparamita can be discerned in the stress on non-conceptual wisdom (prajña) and the apophatic language of Zen literature.

The philosophy of the Huayan school also had an influence on Chinese Chan. One example is the Huayan doctrine of the interpenetration of phenomena which also makes use of native Chinese philosophical concepts such as principle (li) and phenomena (shi). The Huayan theory of the Fourfold Dharmadhatu also influenced the Five Ranks of Dongshan Liangjie (806–869), the founder of the Caodong Chan lineage.

Zen teachings can be likened to "the finger pointing at the moon". Zen teachings point to the moon, awakening, "a realization of the unimpeded interpenetration of the dharmadhatu". But the Zen-tradition also warns against taking its teachings, the pointing finger, to be this insight itself.

Various Zen traditions have varying views on awakening or enlightenment (bodhi). According to Stuart Lachs, one view is that one's mind is already enlightened, this is termed pen chueh in Chinese Buddhism and hongaku in Japanese Zen. Another view is that there is an actual point in time in which one passes from ignorance to realization (Ch. shih-chueh).

Another important issue widely debated in Zen is that of how awakening happens. Beginning with the combative figure of Shenhui (684–758), the idea that there were two ways to enlightenment emerged. One was a sudden way

(McRae: "the position that enlightenment occurs in a single

transformation that is both total and instantaneous") while the other

was the gradual or progressive way (which Shenhui saw as inferior). The issue is discussed in the Platform Sutra, which attempts to resolve the conflict, as well as by later Chan writers.

Caodong\Soto

Japanese Buddhist monk from the Sōtō Zen sect

Sōtō is the Japanese line of the Chinese Caodong school, which was founded during the Tang Dynasty by Dongshan Liangjie. The Sōtō-school has de-emphasized kōans since Gentō Sokuchū (circa 1800), and instead emphasized on shikantaza.

Dogen, the founder of Soto in Japan, emphasized that practice and

awakening cannot be separated. By practicing shikantaza, attainment and

Buddhahood are already being expressed. For Dogen, zazen, or shikantaza, is the essence of Buddhist practice. Gradual cultivation was also recognized by Dongshan Liangjie.

Linji\Rinzai

The Rinzai school is the Japanese lineage of the Chinese Linji school, which was founded during the Tang dynasty by Linji Yixuan.The Rinzai school emphasizes kensho, insight into one's true nature. This is followed by so-called post-satori practice, further practice to attain Buddhahood.

Other Zen-teachers have also expressed sudden insight followed by gradual cultivation. Jinul, a 12th-century Korean Seon

master, followed Zongmi, and also emphasized that insight into our true

nature is sudden, but is to be followed by practice to ripen the

insight and attain full buddhahood. This is also the standpoint of the

contemporary Sanbo Kyodan, according to whom kenshō is at the start of the path to full enlightenment.

To attain this primary insight and to deepen it, zazen and

kōan-study is deemed essential. This trajectory of initial insight

followed by a gradual deepening and ripening is expressed by Linji in

his Three Mysterious Gates and Hakuin Ekaku's Four Ways of Knowing. Another example of depiction of stages on the path are the Ten Bulls, which detail the steps on the path.

Zen scripture

Archaeologist Aurel Stein’s 1907 view of Mogao Cave 16, with altar and sutra scrolls.

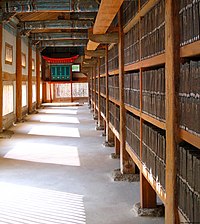

Tablets of the Tripiṭaka Koreana, an early edition of the Chinese Buddhist canon, in Haeinsa Temple, South Korea.

The role of scripture in Zen

Contrary

to the popular image, literature does play a role in the Zen training.

Zen is deeply rooted in the teachings and doctrines of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Classic Zen texts, such as the Platform sutra, contain numerous references to Buddhist canonical sutras. Unsui (Zen-monks), "are expected to become familiar with the classics of the Zen canon".

A review of the early historical documents and literature of early Zen

masters clearly reveals that they were well versed in numerous Mahāyāna sūtras, as well as Mahayana Buddhist philosophy such as Madhyamaka.

Nevertheless, Zen is often pictured as anti-intellectual. This picture of Zen emerged during the Song Dynasty

(960–1297), when Chán became the dominant form of Buddhism in China,

and gained great popularity among the educated and literary classes of

Chinese society. The use of koans, which are highly stylized literary texts, reflects this popularity among the higher classes. The famous saying "do not establish words and letters", attributed in this period to Bodhidharma

...was taken not as a denial of the recorded words of the Buddha or the doctrinal elaborations by learned monks, but as a warning to those who had become confused about the relationship between Buddhist teaching as a guide to the truth and mistook it for the truth itself.

What the Zen tradition emphasizes is that the enlightenment of the Buddha came not through conceptualization but rather through direct insight. But direct insight has to be supported by study and understanding (hori) of the Buddhist teachings and texts. Intellectual understanding without practice is called yako-zen, "wild fox Zen", but "one who has only experience without intellectual understanding is a zen temma, 'Zen devil'".

Grounding Chán in scripture

The early Buddhist schools in China were each based on a specific sutra. At the beginning of the Tang Dynasty, by the time of the Fifth Patriarch Hongren (601–674), the Zen school became established as a separate school of Buddhism. It had to develop a doctrinal tradition of its own to ascertain its position and to ground its teachings in a specific sutra. Various sutras were used for this even before the time of Hongren: the Śrīmālādevī Sūtra (Huike), Awakening of Faith (Daoxin), the Lankavatara Sutra (East Mountain School), the Diamond Sutra (Shenhui), and the Platform Sutra. None of these sutras were decisive though, since the school drew inspiration from a variety of sources.

Subsequently, the Zen tradition produced a rich corpus of written

literature which has become a part of its practice and teaching. Other

influential sutras are the Vimalakirti Sutra, Avatamsaka Sutra, the Shurangama Sutra, and the Mahaparinirvana Sutra.

Zen literature

The Zen-tradition developed a rich textual tradition, based on the

interpretation of the Buddhist teachings and the recorded sayings of

Zen-masters. Important texts are the Platform Sutra (8th century), attributed to Huineng ; the Chán transmission records, teng-lu, such as The Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (Ching-te ch'uan-teng lu), compiled by Tao-yün and published in 1004; the "yü-lü" genre

consisting of the recorded sayings of the masters, and the encounter

dialogues; the koan-collections, such as the "Gateless Gate" and the

"Blue Cliff Record".

Zen organization and institutions

Religion is not only an individual matter, but "also a collective endeavour". Though individual experience and the iconoclastic picture of Zen

are emphasised in the Western world, the Zen-tradition is maintained

and transferred by a high degree of institutionalisation and hierarchy. In Japan, modernity has led to criticism of the formal system and the commencement of lay-oriented Zen-schools such as the Sanbo Kyodan and the Ningen Zen Kyodan. How to organize the continuity of the Zen-tradition in the West, constraining charismatic authority and the derailment it may bring on the one hand, and maintaining the legitimacy and authority by limiting the number of authorized teachers on the other hand, is a challenge for the developing Zen-communities in the West.

Zen narratives

The Chán of the Tang Dynasty, especially that of Mazu and Linji with its emphasis on "shock techniques", in retrospect was seen as a golden age of Chán. This picture has gained great popularity in the West in the 20th century, especially due to the influence of D.T. Suzuki, and further popularized by Hakuun Yasutani and the Sanbo Kyodan. This picture has been challenged, and complemented, since the 1970s by modern scientific research on Zen.

Modern scientific research on the history of Zen discerns three

main narratives concerning Zen, its history and its teachings:

Traditional Zen Narrative (TZN), Buddhist Modernism (BM), Historical and Cultural Criticism (HCC). An external narrative is Nondualism, which claims Zen to be a token of a universal nondualist essence of religions.

History

Chinese Chán

Huike Offering His Arm to Bodhidharma, Sesshū Tōyō (1496).

Zen (Chinese: Chán

禪) Buddhism as we know it today is the result of a long history, with

many changes and contingent factors. Each period had different types of

Zen, some of which remained influential while others vanished. The history of Chán in China

is divided into various periods by different scholars, who generally

distinguish a classical phase and a post-classical period. One way to

outline the history of the Chinese classical period is McRae's division

into four phases or periods: Proto, Early, Middle and Song Dynasty Chán. The post-classical period can also be divided in multiple phases and would also include forms of Chán Buddhist modernisms arising as a reaction to Western imperialism.

Proto-Chán

Proto-Chán (c. 500–600) encompasses the Southern and Northern Dynasties period (420 to 589) and Sui Dynasty (589–618 CE). In this phase, Chán developed in multiple locations in northern China. It was based on the practice of dhyana and is connected to the figures of Bodhidharma and Huike,

though there is little actual historical information about these early

figures and most legendary stories about their life come from later,

mostly Tang sources. An important text from this period is the Two Entrances and Four Practices, found in Dunhuang, and attributed to Bodhidharma. Later sources mention that these figures taught using the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra though there is no direct evidence of this from the earliest sources.

Early Chán

Early Chán refers to early Tang Dynasty (618–750) Chán. The fifth patriarch Daman Hongren (601–674), and his dharma-heir Yuquan Shenxiu (606?–706) were influential in founding the first Chan institution in Chinese history, known as the “East Mountain school” (Dongshan famen). Shenxiu was the most influential and charismatic student of Hongren, he was even invited to the Imperial Court by Empress Wu. Shenxiu also became the target of much criticism by Shenhui (670–762), for his "gradualist" teachings. Shenhui instead promoted the "sudden" teachings of his teacher Huineng (638–713) as well as what later became a very influential Chán classic called the Platform Sutra. Shenhui's propaganda campaign eventually succeeded in elevating Huineng to the status of sixth patriarch of Chinese Chán. The sudden vs. gradual debate that developed in this era came to define later forms of Chan Buddhism.

Middle Chán

The Middle Chán (c. 750–1000) period runs from the An Lushan Rebellion (755–763) to the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960/979). This phase saw the development new schools of Chan. The most important of these schools is the Hongzhou school of Mazu Daoyi (709–788), to which also belong Shitou, Baizhang, and Huangbo.

This school is sometimes seen as the archetypal expression of Chán,

with its emphasis on the personal expression of insight, and its

rejection of positive statements, as well as the importance it placed on

spontaneous and unconventional "questions and answers during an

encounter" (linji wenda) between master and disciple.

However, modern scholars have seen much of the literature which

presents these "iconoclastic" encounters as being later revisions during

the Song era,

and instead see the Hongzhou masters as not being very radical, instead

promoting pretty conservative ideas, such as keeping precepts,

accumulating good karma and practicing meditation.

However, the school did produce innovative teachings and perspectives

such as Mazu's views that "this mind is Buddha" and that "ordinary mind

is the way", which were also critiqued by later figures, such as the

influential Guifeng Zongmi (780–841), for failing to differentiate between ignorance and enlightenment.

By the end of the late Tang, the Hongzhou school was gradually superseded by various regional traditions, which became known as the Five Houses of Chán. Shitou Xiqian (710–790) is regarded as the Patriarch of Cáodòng (Jp. Sōtō) school, while Linji Yixuan (died 867) is regarded as the founder of Línjì (Jp. Rinzai)

school. Both of these traditions were quite influential both in and

outside of China. Another influential Chán master of the late Tang was Xuefeng Yicun.

During the later Tang, the practice of the "encounter dialogue" reached

its full maturity. These formal dialogues between master and disciple

used absurd, illogical and iconoclastic language as well as non-verbal

forms of communication such as the drawing of circles and physical gestures like shouting and hitting. It was also common to write fictional encounter dialogues and attribute them to previous Chán figures. An important text from this period is the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (952), which gives many "encounter-stories", as well as establishing a genealogy of the Chán school.

The Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution

in 845 was devastating for metropolitan Chan, but the Chan school of

Mazu survived, and took a leading role in the Chan of the later Tang.

Song Dynasty Chán

Dahui introduced the method of kan huatou, or "inspecting the critical phrase", of a kōan story. This method was called the "Chan of kōan introspection" (Kanhua Chan).

During Song Dynasty Chán (c. 950–1300), Chán Buddhism took its definitive shape, developed the use of koans for individual study and meditation and formalized its own idealized history with the legend of the Tang "golden age". During the Song, Chán became the largest sect of Chinese Buddhism

and had strong ties to the imperial government which led to the

development of a highly organized system of temple rank and

administration. The dominant form of Song Chán was the Linji school due to support from the scholar-official class and the imperial court. This school developed the study of gong'an

("public case") literature which depicted stories of master student

encounters that were seen as demonstrations of the awakened mind.

During the 12th century, a rivalry emerged between the Linji and the Caodong schools for the support of the scholar-official class. Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091–1157) of the Caodong school emphasized silent illumination or serene reflection (mòzhào) as a means for solitary practice, which could be undertaken by lay-followers. The Linji school's Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) meanwhile, introduced k'an-hua chan ("observing the word-head" chan) which involved meditation on the crucial phrase or "punch line" (hua-tou) of a gong'an.

The Song also saw the syncretism of Chán and Pure Land Buddhism by Yongming Yanshou (904–975) which would later become extremely influential. Yongming also echoed Zongmi's

work in indicating that the values of Taoism and Confucianism could

also be embraced and integrated into Buddhism. Chán also influenced Neo-Confucianism as well as certain forms of Taoism, such as the Quanzhen school.

The classic Chan koan collections, such as the Blue Cliff Record and the Gateless barrier were assembled in this period, which reflect the learned influence of the highly intellectual scholar-official class or "literati" on the development of Chán. In this phase Chán is transported to Japan, and exerts a great influence on Korean Seon via Jinul.

Post-Classical Chán

During the Ming Dynasty, the Chán school was so dominant that all Chinese monks were affiliated with either the Linji school or the Caodong school.

Some scholars see the post-classical phase as being an "age of syncretism." The post-classical period saw the increasing popularity of the dual practice of Chán and Pure Land Buddhism (known as nianfo Chan), as seen in the teachings of Zhongfeng Mingben (1263–1323) and the great reformer Hanshan Deqing

(1546–1623). This became a widespread phenomenon and in time much of

the distinction between them was lost, with many monasteries teaching

both Chán meditation and the Pure Land practice of nianfo. The Ming dynasty

saw increasing efforts by figures such as Yunqi Zhuhong (1535–1615) and

Daguan Zhenke (1543–1603) to revive and reconcile Chan Buddhism with

the practice of scriptural study and writing.

In the beginning of the Qing Dynasty,

Chán was "reinvented", by the "revival of beating and shouting

practices" by Miyun Yuanwu (1566–1642), and the publication of the Wudeng yantong

("The strict transmission of the five Chan schools") by Feiyin

Tongrong’s (1593–1662), a dharma heir of Miyun Yuanwu. The book placed

self-proclaimed Chan monks without proper Dharma transmission in the

category of "lineage unknown" (sifa weixiang), thereby excluding several prominent Caodong-monks.

Modern era

Xuyun was one of the most influential Chán Buddhists of the 19th and 20th centuries.

After further centuries of decline during the Qing Dynasty

(1644–1912), Chán activity was revived again in the 19th and 20th

centuries by a flurry of modernist activity. This period saw the rise of

worldly Chan activism, what is sometimes called Humanistic Buddhism (or more literally "Buddhism for human life", rensheng fojiao), promoted by figures like Jing'an (1851–1912), Yuanying (1878–1953), Taixu (1890–1947), Xuyun (1840–1959) and Yinshun

(1906–2005). These figures promoted social activism to address issues

such as poverty and social injustice, as well as participation in

political movements. They also promoted modern science and scholarship,

including the use of the methods of modern critical scholarship to study

the history of Chan.

Many Chán teachers today trace their lineage back to Xuyun, including Sheng-yen and Hsuan Hua, who have propagated Chán in the West where it has grown steadily through the 20th and 21st centuries.

Chán Buddhism was repressed in China during the 1960s in the Cultural Revolution, but in the subsequent reform and opening up period in the 1970s, a revival of Chinese Buddhism has been taking place on the mainland, while Buddhism has a significant following in Taiwan and Hong Kong as well as among Overseas Chinese.

Spread outside of China

Vietnamese Thiền

Thích Nhất Hạnh leading a namo avalokiteshvaraya chanting session with monastics from his Order of Interbeing, Germany 2010.

Chan was introduced to Vietnam during the early Chinese occupation periods (111 BCE to 939 CE) as Thiền. During the Lý (1009–1225) and Trần

(1225 to 1400) dynasties, Thiền rose to prominence among the elites and

the royal court and a new native tradition was founded, the Trúc Lâm ("Bamboo Grove") school, which also contained Confucian and Taoist influences. In the 17th century, the Linji school was brought to Vietnam as the Lâm Tế, which also mixed Chan and Pure land. Lâm Tế remains the largest monastic order in the country today.

Modern Vietnamese Thiền is influenced by Buddhist modernism. Important figures include Thiền master Thích Thanh Từ (1924–), the activist and popularizer Thích Nhất Hạnh (1926–) and the philosopher Thích Thiên-Ân. Vietnamese Thiền is eclectic and inclusive, bringing in many practices such as breath meditation, nianfo, mantra, Theravada influences, chanting, sutra recitation and engaged Buddhism activism.

Korean Seon

Jogyesa is the headquarters of the Jogye Order. The temple was first established in 1395, at the dawn of the Joseon Dynasty.

Seon (선) was gradually transmitted into Korea during the late Silla period (7th through 9th centuries) as Korean monks began to travel to China to learn the newly developing Chan tradition of Mazu Daoyi and returned home to establish the Chan school. They established the initial Seon schools of Korea which were known as the "nine mountain schools" (九山, gusan).

Seon received its most significant impetus and consolidation from the Goryeo monk Jinul (1158–1210), who is considered the most influential figure in the formation of the mature Seon school. He founded the Jogye Order, which remains the largest Seon tradition in Korea today. Jinul founded the Songgwangsa

temple as a new center of Seon study and practice. Jinul also wrote

extensive works on Seon, developing a comprehensive system of thought

and practice. From Dahui Zonggao, Jinul adopted the hwadu method, which remains the main meditation form taught in Seon today.

Buddhism was mostly suppressed during the strictly Confucian Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), and the number of monasteries and clergy sharply declined. The period of Japanese occupation

also brought numerous modernist ideas and changes to Korean Seon. Some

monks began to adopt the Japanese practice of marrying and having

families, while others such as Yongseong, worked to resist the Japanese occupation. Today, the largest Seon school, the Jogye, enforces celibacy, while the second largest, the Taego Order, allows for married priests. Important modernist figures which influenced contemporary Seon include Seongcheol and Gyeongheo. Seon has also been transmitted to West, with new traditions such as the Kwan Um School of Zen.

Japanese Zen

Zen was not introduced as a separate school until the 12th century, when Myōan Eisai traveled to China and returned to establish a Linji lineage, which eventually perished. Decades later, Nanpo Shōmyō (南浦紹明) (1235–1308) also studied Linji teachings in China before founding the Japanese Otokan lineage, the most influential and only surviving lineage of Rinzai in Japan. In 1215, Dōgen, a younger contemporary of Eisai's, journeyed to China himself, where he became a disciple of the Caodong master Tiantong Rujing. After his return, Dōgen established the Sōtō school, the Japanese branch of Caodong.

The three traditional schools of Zen in contemporary Japan are the Sōtō (曹洞), Rinzai (臨済), and Ōbaku (黃檗).

Of these, Sōtō is the largest, and Ōbaku the smallest, with Rinzai in

the middle. These schools are further divided into subschools by head

temple, with two head temples for Sōtō (Sōji-ji and Eihei-ji, with Sōji-ji having a much larger network), fourteen head temples for Rinzai, and one head temple (Manpuku-ji)

for Ōbaku, for a total of 17 head temples. The Rinzai head temples,

which are most numerous, have substantial overlap with the traditional Five Mountain System, and include Myoshin-ji, Nanzen-ji, Tenryū-ji, Daitoku-ji, and Tofuku-ji, among others.

Besides these traditional organizations, there are modern Zen

organisations which have especially attracted Western lay followers,

namely the Sanbo Kyodan and the FAS Society.

Zen in the West

Although it is difficult to trace the precise moment when the West

first became aware of Zen as a distinct form of Buddhism, the visit of Soyen Shaku, a Japanese Zen monk, to Chicago during the World Parliament of Religions

in 1893 is often pointed to as an event that enhanced the profile of

Zen in the Western world. It was during the late 1950s and the early

1960s that the number of Westerners other than the descendants of Asian

immigrants who were pursuing a serious interest in Zen began to reach a

significant level. Japanese Zen has gained the greatest popularity in the West. The various books on Zen by Reginald Horace Blyth, Alan Watts, Philip Kapleau and D. T. Suzuki

published between 1950 and 1975, contributed to this growing interest

in Zen in the West, as did the interest on the part of beat poets such

as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder. In 1958, the literary magazine Chicago Review played a significant role in introducing Zen to the American literary community when it published a special issue on Zen featuring the aforementioned beat poets and works in translation.