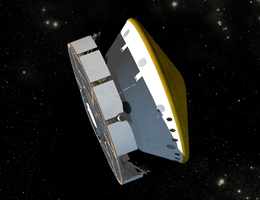

MSL cruise configuration

| |

| Mission type | Mars rover |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 2011-070A |

| SATCAT no. | 37936 |

| Website | http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl/ |

| Mission duration | Primary: 669 Martian sols (687 days) Elapsed: 2444 sols (2511 days) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | JPL, Lockheed Martin |

| Launch mass | 3,839 kg (8,463 lb) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | November 26, 2011, 15:02:00.211 UTC |

| Rocket | Atlas V 541 (AV-028) |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-41 |

| Contractor | United Launch Alliance |

| Mars rover | |

| Landing date | August 6, 2012, 05:17 UTC SCET MSD 49269 05:50:16 AMT |

| Landing site | "Bradbury Landing" in Gale Crater 4.5895°S 137.4417°E |

| |

Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) is a robotic space probe mission to Mars launched by NASA on November 26, 2011, which successfully landed Curiosity, a Mars rover, in Gale Crater on August 6, 2012. The overall objectives include investigating Mars' habitability, studying its climate and geology, and collecting data for a manned mission to Mars. The rover carries a variety of scientific instruments designed by an international team.

Overview

Hubble

view of Mars: Gale crater can be seen. Slightly left and south of

center, it's a small dark spot with dust trailing southward from it.

MSL successfully carried out the most accurate Martian landing of any

known spacecraft, hitting a small target landing ellipse of only 7 by

20 km (4.3 by 12.4 mi), in the Aeolis Palus

region of Gale Crater. In the event, MSL achieved a landing 2.4 km

(1.5 mi) east and 400 m (1,300 ft) north of the center of the target. This location is near the mountain Aeolis Mons (a.k.a. "Mount Sharp"). The rover mission is set to explore for at least 687 Earth days (1 Martian year) over a range of 5 by 20 km (3.1 by 12.4 mi).

The Mars Science Laboratory mission is part of NASA's Mars Exploration Program, a long-term effort for the robotic exploration of Mars that is managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of California Institute of Technology. The total cost of the MSL project is about US$2.5 billion.

Previous successful U.S. Mars rovers include Sojourner from the Mars Pathfinder mission and the Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity. Curiosity is about twice as long and five times as heavy as Spirit and Opportunity, and carries over ten times the mass of scientific instruments.

Goals and objectives

MSL self-portrait from Gale Crater sol 85 (October 31, 2012).

The MSL mission has four scientific goals: Determine the landing site's habitability including the role of water, the study of the climate and the geology of Mars. It is also useful preparation for a future manned mission to Mars.

To contribute to these goals, MSL has eight main scientific objectives:

- Biological

- (1) Determine the nature and inventory of organic carbon compounds

- (2) Investigate the chemical building blocks of life (carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur)

- (3) Identify features that may represent the effects of biological processes (biosignatures)

- Geological and geochemical

- (4) Investigate the chemical, isotopic, and mineralogical composition of the Martian surface and near-surface geological materials

- (5) Interpret the processes that have formed and modified rocks and soils

- Planetary process

- (6) Assess long-timescale (i.e., 4-billion-year) Martian atmospheric evolution processes

- (7) Determine present state, distribution, and cycling of water and carbon dioxide

- Surface radiation

- (8) Characterize the broad spectrum of surface radiation, including cosmic radiation, solar particle events and secondary neutrons. As part of its exploration, it also measured the radiation exposure in the interior of the spacecraft as it traveled to Mars, and it is continuing radiation measurements as it explores the surface of Mars. This data would be important for a future manned mission.

About one year into the surface mission, and having assessed that

ancient Mars could have been hospitable to microbial life, the MSL

mission objectives evolved to developing predictive models for the

preservation process of organic compounds and biomolecules; a branch of paleontology called taphonomy.

Specifications

Spacecraft

Mars Science Laboratory in final assembly

Diagram of the MSL spacecraft: 1- Cruise stage; 2- Backshell; 3- Descent stage; 4- Curiosity rover; 5- Heat shield; 6- Parachute

The spacecraft flight system had a mass at launch of 3,893 kg (8,583 lb), consisting of an Earth-Mars fueled cruise stage (539 kg (1,188 lb)), the entry-descent-landing (EDL) system (2,401 kg (5,293 lb) including 390 kg (860 lb) of landing propellant), and a 899 kg (1,982 lb) mobile rover with an integrated instrument package.

The MSL spacecraft includes spaceflight-specific instruments, in

addition to utilizing one of the rover instruments — Radiation

assessment detector (RAD) — during the spaceflight transit to Mars.

- MSL EDL Instrument (MEDLI): The MEDLI project's main objective is to measure aerothermal environments, sub-surface heat shield material response, vehicle orientation, and atmospheric density. The MEDLI instrumentation suite was installed in the heatshield of the MSL entry vehicle. The acquired data will support future Mars missions by providing measured atmospheric data to validate Mars atmosphere models and clarify the lander design margins on future Mars missions. MEDLI instrumentation consists of three main subsystems: MEDLI Integrated Sensor Plugs (MISP), Mars Entry Atmospheric Data System (MEADS) and the Sensor Support Electronics (SSE).

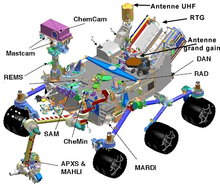

Rover

Color-coded rover diagram

Curiosity rover has a mass of 899 kg (1,982 lb), can travel up

to 90 m (300 ft) per hour on its six-wheeled rocker-bogie system, is

powered by a multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG), and communicates in both X band and UHF bands.

- Computers: The two identical on-board rover computers, called "Rover Compute Element" (RCE), contain radiation-hardened memory to tolerate the extreme radiation from space and to safeguard against power-off cycles. Each computer's memory includes 256 KB of EEPROM, 256 MB of DRAM, and 2 GB of flash memory.[30] This compares to 3 MB of EEPROM, 128 MB of DRAM, and 256 MB of flash memory used in the Mars Exploration Rovers.[31]

- The RCE computers use the RAD750 CPU (a successor to the RAD6000 CPU used in the Mars Exploration Rovers) operating at 200 MHz.[32][33][34] The RAD750 CPU is capable of up to 400 MIPS, while the RAD6000 CPU is capable of up to 35 MIPS. Of the two on-board computers, one is configured as backup, and will take over in the event of problems with the main computer.

- The rover has an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) that provides 3-axis information on its position, which is used in rover navigation. The rover's computers are constantly self-monitoring to keep the rover operational, such as by regulating the rover's temperature. Activities such as taking pictures, driving, and operating the instruments are performed in a command sequence that is sent from the flight team to the rover.

The rover's computers function on VxWorks, a real-time operating system from Wind River Systems.

During the trip to Mars, VxWorks ran applications dedicated to the

navigation and guidance phase of the mission, and also had a

pre-programmed software sequence for handling the complexity of the

entry-descent-landing. Once landed, the applications were replaced with

software for driving on the surface and performing scientific

activities.

Goldstone antenna can receive signals

Wheels of a working sibling to Curiosity. The Morse code pattern (for "JPL")

is represented by small (dot) and large (dash) holes in three

horizontal lines on the wheels. The code on each line is read from right

to left.

- Communications: Curiosity is equipped with several means of communication, for redundancy. An X band Small Deep Space Transponder for communication directly to Earth via the NASA Deep Space Network and a UHF Electra-Lite software-defined radio for communicating with Mars orbiters. The X-band system has one radio, with a 15 W power amplifier, and two antennas: a low-gain omnidirectional antenna that can communicate with Earth at very low data rates (15 bit/s at maximum range), regardless of rover orientation, and a high-gain antenna that can communicate at speeds up to 32 kbit/s, but must be aimed. The UHF system has two radios (approximately 9 W transmit power), sharing one omnidirectional antenna. This can communicate with the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter (ODY) at speeds up to 2 Mbit/s and 256 kbit/s, respectively, but each orbiter is only able to communicate with Curiosity for about 8 minutes per day. The orbiters have larger antennas and more powerful radios, and can relay data to Earth faster than the rover could do directly. Therefore, most of the data returned by Curiosity (MSL), is via the UHF relay links with MRO and ODY. The data return via the communication infrastructure as implemented at MSL, and observed during the first 10 days was approximately 31 megabytes per day.

- Typically 225 kbit/day of commands are transmitted to the rover directly from Earth, at a data rate of 1–2 kbit/s, during a 15-minute (900 second) transmit window, while the larger volumes of data collected by the rover are returned via satellite relay. The one-way communication delay with Earth varies from 4 to 22 minutes, depending on the planets' relative positions, with 12.5 minutes being the average.

- At landing, telemetry was monitored by the 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and ESA's Mars Express. Odyssey is capable of relaying UHF telemetry back to Earth in real time. The relay time varies with the distance between the two planets and took 13:46 minutes at the time of landing.

- Mobility systems: Curiosity is equipped with six wheels in a rocker-bogie suspension, which also served as landing gear for the vehicle, unlike its smaller predecessors. The wheels are significantly larger (50 centimeters (20 in) diameter) than those used on previous rovers. Each wheel has cleats and is independently actuated and geared, providing for climbing in soft sand and scrambling over rocks. The four corner wheels can be independently steered, allowing the vehicle to turn in place as well as execute arcing turns. Each wheel has a pattern that helps it maintain traction and leaves patterned tracks in the sandy surface of Mars. That pattern is used by on-board cameras to judge the distance traveled. The pattern itself is Morse code for "JPL" (•−−− •−−• •−••). Based on the center of mass, the vehicle can withstand a tilt of at least 50 degrees in any direction without overturning, but automatic sensors will limit the rover from exceeding 30-degree tilts.

Instruments

| Main instruments |

|---|

| APXS – Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer |

| ChemCam – Chemistry and Camera complex |

| CheMin – Chemistry and Mineralogy |

| DAN – Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons |

| Hazcam – Hazard Avoidance Camera |

| MAHLI – Mars Hand Lens Imager |

| MARDI – Mars Descent Imager |

| MastCam – Mast Camera |

| MEDLI – MSL EDL Instrument |

| Navcam – Navigation Camera |

| RAD – Radiation assessment detector |

| REMS – Rover Environmental Monitoring Station |

| SAM – Sample Analysis at Mars |

The shadow of Curiosity and Aeolis Mons ("Mount Sharp")

The general analysis strategy begins with high resolution cameras to

look for features of interest. If a particular surface is of interest, Curiosity

can vaporize a small portion of it with an infrared laser and examine

the resulting spectra signature to query the rock's elemental

composition. If that signature intrigues, the rover will use its long

arm to swing over a microscope and an X-ray spectrometer to take a closer look. If the specimen warrants further analysis, Curiosity can drill into the boulder and deliver a powdered sample to either the SAM or the CheMin analytical laboratories inside the rover.

- Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS): This device can irradiate samples with alpha particles and map the spectra of X-rays that are re-emitted for determining the elemental composition of samples.

- CheMin: CheMin is short for 'Chemistry and Mineralogy', and it is an X-ray diffraction and X-ray fluorescence analyzer. It will identify and quantify the minerals present in rocks and soil and thereby assess the involvement of water in their formation, deposition, or alteration. In addition, CheMin data will be useful in the search for potential mineral biosignatures, energy sources for life or indicators for past habitable environments.

- Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM): The SAM instrument suite will analyze organics and gases from both atmospheric and solid samples. This include oxygen and carbon isotope ratios in carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) in the atmosphere of Mars in order to distinguish between their geochemical or biological origin.

Comparison of Radiation Doses – includes the amount detected on the trip from Earth to Mars by the RAD on the MSL (2011–2013).

- Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD): This instrument was the first of ten MSL instruments to be turned on. Both en route and on the planet's surface, it will characterize the broad spectrum of radiation encountered in the Martian environment. Turned on after launch, it recorded several radiation spikes caused by the Sun. On May 31, 2013, NASA scientists reported that a possible manned mission to Mars may involve a great radiation risk based on the amount of energetic particle radiation detected by the RAD on the Mars Science Laboratory while traveling from the Earth to Mars in 2011–2012.

- Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN): A pulsed neutron source and detector for measuring hydrogen or ice and water at or near the Martian surface. On August 18, 2012 (sol 12) the Russian science instrument, DAN, was turned on, marking the success of a Russian-American collaboration on the surface of Mars and the first working Russian science instrument on the Martian surface since Mars 3 stopped transmitting over forty years ago. The instrument is designed to detect subsurface water.

- Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS): Meteorological package and an ultraviolet sensor provided by Spain and Finland. It measures humidity, pressure, temperatures, wind speeds, and ultraviolet radiation.

- Cameras: Curiosity has seventeen cameras overall. 12 engineering cameras (Hazcams and Navcams) and five science cameras. MAHLI, MARDI, and MastCam cameras were developed by Malin Space Science Systems and they all share common design components, such as on-board electronic imaging processing boxes, 1600×1200 CCDs, and a RGB Bayer pattern filter.

- MastCam: This system provides multiple spectra and true-color imaging with two cameras.

- Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI): This system consists of a camera mounted to a robotic arm on the rover, used to acquire microscopic images of rock and soil. It has white and ultraviolet LEDs for illumination.

- ChemCam: Designed by Roger Wiens is a system of remote sensing instruments used to erode the Martian surface up to 10 meters away and measure the different components that make up the land. The payload includes the first laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) system to be used for planetary science, and Curiosity's fifth science camera, the remote micro-imager (RMI). The RMI provides black-and-white images at 1024×1024 resolution in a 0.02 radian (1.1-degree) field of view. This is approximately equivalent to a 1500 mm lens on a 35 mm camera.

MARDI views the surface

- Mars Descent Imager (MARDI): During part of the descent to the Martian surface, MARDI acquired 4 color images per second, at 1600×1200 pixels, with a 0.9-millisecond exposure time. Images were taken 4 times per second, starting shortly before heatshield separation at 3.7 km altitude, until a few seconds after touchdown. This provided engineering information about both the motion of the rover during the descent process, and science information about the terrain immediately surrounding the rover. NASA descoped MARDI in 2007, but Malin Space Science Systems contributed it with its own resources. After landing it could take 1.5 mm (0.059 in) per pixel views of the surface, the first of these post-landing photos were taken by August 27, 2012 (sol 20).

- Engineering cameras: There are 12 additional cameras that support mobility:

- Hazard avoidance cameras (Hazcams): The rover has a pair of black and white navigation cameras (Hazcams) located on each of its four corners. These provide closed-up views of potential obstacles about to go under the wheels.

- Navigation cameras (Navcams): The rover uses two pairs of black and white navigation cameras mounted on the mast to support ground navigation. These provide a longer-distance view of the terrain ahead.

History

MSL's cruise stage on Earth

The Mars Science Laboratory was recommended by United States National

Research Council Decadal Survey committee as the top priority

middle-class Mars mission in 2003. NASA called for proposals for the rover's scientific instruments in April 2004, and eight proposals were selected on December 14 of that year. Testing and design of components also began in late 2004, including Aerojet's designing of a monopropellant engine with the ability to throttle from 15–100 percent thrust with a fixed propellant inlet pressure.

Cost overruns, delays, and launch

By November 2008 most hardware and software development was complete, and testing continued.

At this point, cost overruns were approximately $400 million. In the

attempts to meet the launch date, several instruments and a cache for

samples were removed and other instruments and cameras were simplified

to simplify testing and integration of the rover. The next month, NASA delayed the launch to late 2011 because of inadequate testing time.

Eventually the costs for developing the rover reached $2.47 billion,

that for a rover that initially had been classified as a medium-cost

mission with a maximum budget of $650 million, yet NASA still had to ask

for an additional $82 million to meet the planned November launch. As

of 2012, the project suffered an 84 percent overrun.

MSL launched on an Atlas V rocket from Cape Canaveral on November 26, 2011.

On January 11, 2012, the spacecraft successfully refined its trajectory

with a three-hour series of thruster-engine firings, advancing the

rover's landing time by about 14 hours. When MSL was launched, the

program's director was Doug McCuistion of NASA's Planetary Science Division.

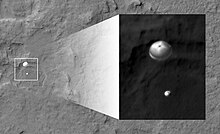

Curiosity successfully landed in the Gale Crater at 05:17:57.3 UTC on August 6, 2012, and transmitted Hazcam images confirming orientation. Due to the Mars-Earth distance at the time of landing and the limited speed of radio signals, the landing was not registered on Earth for another 14 minutes. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter sent a photograph of Curiosity descending under its parachute, taken by its HiRISE camera, during the landing procedure.

Six senior members of the Curiosity team presented a news conference a few hours after landing, they were: John Grunsfeld, NASA associate administrator; Charles Elachi, director, JPL; Peter Theisinger, MSL project manager; Richard Cook, MSL deputy project manager; Adam Steltzner, MSL entry, descent and landing (EDL) lead; and John Grotzinger, MSL project scientist.

Naming

Between

March 23–29, 2009, the general public ranked nine finalist rover names

(Adventure, Amelia, Journey, Perception, Pursuit, Sunrise, Vision,

Wonder, and Curiosity) through a public poll on the NASA website. On May 27, 2009, the winning name was announced to be Curiosity. The name had been submitted in an essay contest by Clara Ma, a then sixth-grader from Kansas.

Curiosity is the passion that drives us through our everyday lives. We have become explorers and scientists with our need to ask questions and to wonder.

— Clara Ma, NASA/JPL Name the Rover contest

Landing site selection

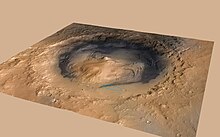

Aeolis Mons rises from the middle of Gale Crater – Green dot marks the Curiosity rover landing site in Aeolis Palus – North is down

Over 60 landing sites were evaluated, and by July 2011 Gale crater

was chosen. A primary goal when selecting the landing site was to

identify a particular geologic environment, or set of environments, that

would support microbial life. Planners looked for a site that could

contribute to a wide variety of possible science objectives. They

preferred a landing site with both morphologic and mineralogical

evidence for past water. Furthermore, a site with spectra indicating

multiple hydrated minerals was preferred; clay minerals and sulfate salts would constitute a rich site. Hematite, other iron oxides, sulfate minerals, silicate minerals, silica, and possibly chloride minerals were suggested as possible substrates for fossil preservation. Indeed, all are known to facilitate the preservation of fossil morphologies and molecules on Earth.

Difficult terrain was favored for finding evidence of livable

conditions, but the rover must be able to safely reach the site and

drive within it.

Engineering constraints called for a landing site less than 45°

from the Martian equator, and less than 1 km above the reference datum. At the first MSL Landing Site workshop, 33 potential landing sites were identified. By the end of the second workshop in late 2007, the list was reduced to six; in November 2008, project leaders at a third workshop reduced the list to these four landing sites:

| Name | Location | Elevation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eberswalde Crater Delta | 23.86°S 326.73°E | −1,450 m (−4,760 ft) | Ancient river delta. |

| Holden Crater Fan | 26.37°S 325.10°E | −1,940 m (−6,360 ft) | Dry lake bed. |

| Gale Crater | 4.49°S 137.42°E | −4,451 m (−14,603 ft) | Features 5 km (3.1 mi) tall mountain of layered material near center. Selected. |

| Mawrth Vallis Site 2 | 24.01°N 341.03°E | −2,246 m (−7,369 ft) | Channel carved by catastrophic floods. |

A fourth landing site workshop was held in late September 2010, and the fifth and final workshop May 16–18, 2011. On July 22, 2011, it was announced that Gale Crater had been selected as the landing site of the Mars Science Laboratory mission.

Launch

The MSL launched from Cape Canaveral.

Launch vehicle

The Atlas V launch vehicle is capable of launching up to 8,290 kg (18,280 lb) to geostationary transfer orbit. The Atlas V was also used to launch the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the New Horizons probe.

The first and second stages, along with the solid rocket motors, were stacked on October 9, 2011 near the launch pad. The fairing containing MSL was transported to the launch pad on November 3, 2011.

Launch event

MSL was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 41 on November 26, 2011, at 15:02 UTC via the Atlas V 541 provided by United Launch Alliance. This two stage rocket includes a 3.8 m (12 ft) Common Core Booster (CCB) powered by one RD-180 engine, four solid rocket boosters (SRB), and one Centaur second stage with a 5 m (16 ft) diameter payload fairing. The NASA Launch Services Program coordinated the launch via the NASA Launch Services (NLS) I Contract.

Cruise

Animation of Mars Science Laboratory's trajectory

Earth · Mars · Mars Science Laboratory

Earth · Mars · Mars Science Laboratory

Cruise stage

The

cruise stage carried the MSL spacecraft through the void of space and

delivered it to Mars. The interplanetary trip covered the distance of

352 million miles in 253 days. The cruise stage has its own miniature propulsion system, consisting of eight thrusters using hydrazine fuel in two titanium tanks. It also has its own electric power system, consisting of a solar array

and battery for providing continuous power. Upon reaching Mars, the

spacecraft stopped spinning and a cable cutter separated the cruise

stage from the aeroshell. Then the cruise stage was diverted into a separate trajectory into the atmosphere. In December 2012, the debris field from the cruise stage was located by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Since the initial size, velocity, density and impact angle of the

hardware are known, it will provide information on impact processes on

the Mars surface and atmospheric properties.

Mars transfer orbit

The MSL spacecraft departed Earth orbit and was inserted into a heliocentric Mars transfer orbit on November 26, 2011, shortly after launch, by the Centaur upper stage of the Atlas V launch vehicle. Prior to Centaur separation, the spacecraft was spin-stabilized at 2 rpm for attitude control during the 36,210 km/h (22,500 mph) cruise to Mars.

During cruise, eight thrusters arranged in two clusters were used as actuators to control spin rate and perform axial or lateral trajectory correction maneuvers. By spinning about its central axis, it maintained a stable attitude.

Along the way, the cruise stage performed four trajectory correction

maneuvers to adjust the spacecraft's path toward its landing site. Information was sent to mission controllers via two X-band antennas.

A key task of the cruise stage was to control the temperature of all

spacecraft systems and dissipate the heat generated by power sources,

such as solar cells and motors, into space. In some systems, insulating blankets kept sensitive science instruments warmer than the near-absolute zero temperature of space. Thermostats monitored temperatures and switched heating and cooling systems on or off as needed.

Entry, descent and landing (EDL)

EDL spacecraft system

Landing a large mass on Mars is particularly challenging as the atmosphere is too thin for parachutes and aerobraking alone to be effective, while remaining thick enough to create stability and impingement problems when decelerating with retrorockets. Although some previous missions have used airbags to cushion the shock of landing, Curiosity rover is too heavy for this to be an option. Instead, Curiosity

was set down on the Martian surface using a new high-accuracy entry,

descent, and landing (EDL) system that was part of the MSL spacecraft

descent stage. The mass of this EDM system, including parachute, sky

crane, fuel and aeroshell, is 2,401 kg (5,293 lb). The novel EDL system placed Curiosity within a 20 by 7 km (12.4 by 4.3 mi) landing ellipse, in contrast to the 150 by 20 km (93 by 12 mi) landing ellipse of the landing systems used by the Mars Exploration Rovers.

The entry-descent-landing (EDL) system differs from those used

for other missions in that it does not require an interactive,

ground-generated mission plan. During the entire landing phase, the

vehicle acts autonomously, based on pre-loaded software and parameters. The EDL system was based on a Viking-derived

aeroshell structure and propulsion system for a precision guided entry

and soft landing, in contrasts with the airbag landings that were used

in the mid-1990s by the Mars Pathfinder and Mars Exploration Rover

missions. The spacecraft employed several systems in a precise order,

with the entry, descent and landing sequence broken down into four parts—described below as the spaceflight events unfolded on August 6, 2012.

EDL event–August 6, 2012

Martian atmosphere entry events from cruise stage separation to parachute deployment

Despite its late hour, particularly on the east coast of the United States where it was 1:31 a.m.,

the landing generated significant public interest. 3.2 million watched

the landing live with most watching online instead of on television via NASA TV or cable news networks covering the event live.

The final landing place for the rover was less than 2.4 km (1.5 mi)

from its target after a 563,270,400 km (350,000,000 mi) journey. In addition to streaming and traditional video viewing, JPL made Eyes on the Solar System, a three-dimensional real time simulation of entry, descent and landing based on real data. Curiosity's touchdown time as represented in the software, based on JPL predictions, was less than 1 second different than reality.

The EDL phase of the MSL spaceflight mission to Mars took only

seven minutes and unfolded automatically, as programmed by JPL engineers

in advance, in a precise order, with the entry, descent and landing

sequence occurring in four distinct event phases.

Guided entry

The guided entry is the phase that allowed the spacecraft to steer with accuracy to its planned landing site

Precision guided entry made use of onboard computing ability to steer

itself toward the pre-determined landing site, improving landing

accuracy from a range of hundreds of kilometers to 20 kilometers

(12 mi). This capability helped remove some of the uncertainties of

landing hazards that might be present in larger landing ellipses. Steering was achieved by the combined use of thrusters and ejectable balance masses. The ejectable balance masses shift the capsule center of mass enabling generation of a lift vector during the atmospheric phase. A navigation computer integrated the measurements to estimate the position and attitude

of the capsule that generated automated torque commands. This was the

first planetary mission to use precision landing techniques.

The rover was folded up within an aeroshell that protected it during the travel through space and during the atmospheric entry

at Mars. Ten minutes before atmospheric entry the aeroshell separated

from the cruise stage that provided power, communications and propulsion

during the long flight to Mars. One minute after separation from the

cruise stage thrusters on the aeroshell fired to cancel out the

spacecraft's 2-rpm rotation and achieved an orientation with the heat

shield facing Mars in preparation for Atmospheric entry. The heat shield is made of phenolic impregnated carbon ablator (PICA). The 4.5 m (15 ft) diameter heat shield, which is the largest heat shield ever flown in space, reduced the velocity of the spacecraft by ablation against the Martian atmosphere,

from the atmospheric interface velocity of approximately 5.8 km/s

(3.6 mi/s) down to approximately 470 m/s (1,500 ft/s), where parachute

deployment was possible about four minutes later. One minute and 15

seconds after entry the heat shield experienced peak temperatures of up

to 2,090 °C (3,790 °F) as atmospheric pressure converted kinetic energy

into heat. Ten seconds after peak heating, that deceleration peaked out

at 15 g.

Much of the reduction of the landing precision error was

accomplished by an entry guidance algorithm, derived from the algorithm

used for guidance of the Apollo Command Modules returning to Earth in the Apollo program.

This guidance uses the lifting force experienced by the aeroshell to

"fly out" any detected error in range and thereby arrive at the targeted

landing site. In order for the aeroshell to have lift, its center of

mass is offset from the axial centerline that results in an off-center

trim angle in atmospheric flight. This is accomplished by a series of

ejectable ballast masses consisting of two 75 kg (165 lb) tungsten weights that were jettisoned minutes before atmospheric entry. The lift vector was controlled by four sets of two reaction control system

(RCS) thrusters that produced approximately 500 N (110 lbf) of thrust

per pair. This ability to change the pointing of the direction of lift

allowed the spacecraft to react to the ambient environment, and steer

toward the landing zone. Prior to parachute deployment the entry vehicle

ejected more ballast mass consisting of six 25 kg (55 lb) tungsten

weights such that the center of gravity offset was removed.

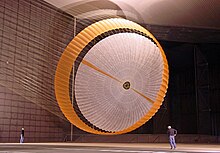

Parachute descent

MSL's parachute is 16 m (52 ft) in diameter.

NASA's Curiosity rover and its parachute were spotted by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter as the probe descended to the surface. August 6, 2012.

When the entry phase was complete and the capsule slowed to about

470 m/s (1,500 ft/s) at about 10 km (6.2 mi) altitude, the supersonic parachute deployed, as was done by previous landers such as Viking,

Mars Pathfinder and the Mars Exploration Rovers. The parachute has 80

suspension lines, is over 50 m (160 ft) long, and is about 16 m (52 ft)

in diameter. Capable of being deployed at Mach 2.2, the parachute can generate up to 289 kN (65,000 lbf) of drag force in the Martian atmosphere.

After the parachute was deployed, the heat shield separated and fell

away. A camera beneath the rover acquired about 5 frames per second

(with resolution of 1600×1200 pixels) below 3.7 km (2.3 mi) during a

period of about 2 minutes until the rover sensors confirmed successful

landing. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter team were able to acquire an image of the MSL descending under the parachute.

Powered descent

The powered descent stage

Following the parachute braking, at about 1.8 km (1.1 mi) altitude,

still travelling at about 100 m/s (220 mph), the rover and descent stage

dropped out of the aeroshell. The descent stage is a platform above the rover with eight variable thrust monopropellant hydrazine

rocket thrusters on arms extending around this platform to slow the

descent. Each rocket thruster, called a Mars Lander Engine (MLE), produces 400 to 3,100 N (90 to 697 lbf) of thrust and were derived from those used on the Viking landers.

A radar altimeter measured altitude and velocity, feeding data to the

rover's flight computer. Meanwhile, the rover transformed from its

stowed flight configuration to a landing configuration while being

lowered beneath the descent stage by the "sky crane" system.

Sky crane

Entry events from parachute deployment through powered descent ending at sky crane flyaway

Artist's conceptIon of Curiosity being lowered from the rocket-powered descent stage.

For several reasons, a different landing system was chosen for MSL compared to previous Mars landers and rovers. Curiosity was considered too heavy to use the airbag landing system as used on the Mars Pathfinder and Mars Exploration Rovers. A legged lander approach would have caused several design problems.

It would have needed to have engines high enough above the ground when

landing not to form a dust cloud that could damage the rover's

instruments. This would have required long landing legs that would need

to have significant width to keep the center of gravity low. A legged

lander would have also required ramps so the rover could drive down to

the surface, which would have incurred extra risk to the mission on the

chance rocks or tilt would prevent Curiosity from being able to

drive off the lander successfully. Faced with these challenges, the MSL

engineers came up with a novel alternative solution: the sky crane. The sky crane system lowered the rover with a 7.6 m (25 ft) tether to a soft landing—wheels down—on the surface of Mars.

This system consists of a bridle lowering the rover on three nylon

tethers and an electrical cable carrying information and power between

the descent stage and rover. As the support and data cables unreeled,

the rover's six motorized wheels snapped into position. At roughly 7.5 m

(25 ft) below the descent stage the sky crane system slowed to a halt

and the rover touched down. After the rover touched down, it waited two

seconds to confirm that it was on solid ground by detecting the weight

on the wheels and fired several pyros

(small explosive devices) activating cable cutters on the bridle and

umbilical cords to free itself from the descent stage. The descent stage

then flew away to a crash landing 650 m (2,100 ft) away. The sky crane concept had never been used in missions before.

Landing site

Gale Crater is the MSL landing site. Within Gale Crater is a mountain, named Aeolis Mons ("Mount Sharp"), of layered rocks, rising about 5.5 km (18,000 ft) above the crater floor, that Curiosity will investigate. The landing site is a smooth region in "Yellowknife" Quad 51 of Aeolis Palus

inside the crater in front of the mountain. The target landing site

location was an elliptical area 20 by 7 km (12.4 by 4.3 mi). Gale Crater's diameter is 154 km (96 mi).

The landing location for the rover was less than 2.4 km (1.5 mi)

from the center of the planned landing ellipse, after a 563,000,000 km

(350,000,000 mi) journey. NASA named the rover landing site Bradbury Landing on sol 16, August 22, 2012. According to NASA, an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 heat-resistant bacterial spores were on Curiosity at launch, and as much as 1,000 times that number may not have been counted.