Anarchism has had a special interest on the issue of education from the works of William Godwin and Max Stirner onwards.

A wide diversity of issues related to education have gained the attention of anarchist theorists and activists. They have included the role of education in social control and socialization, the rights and liberties of youth and children within educational contexts, the inequalities encouraged by current educational systems, the influence of state and religious ideologies in the education of people, the division between social and manual work and its relationship with education, sex education and art education.

Various alternatives to contemporary mainstream educational systems and their problems have been proposed by anarchists which have gone from alternative education systems and environments, self-education, advocacy of youth and children rights, and freethought activism.

Early anarchist views on education

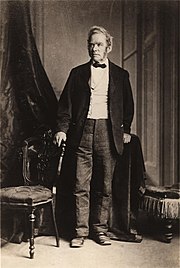

William Godwin

For English enlightenment anarchist William Godwin education was "the main means by which change would be achieved." Godwin saw that the main goal of education should be the promotion of happiness.

For Godwin, education had to have "A respect for the child’s autonomy

which precluded any form of coercion", "A pedagogy that respected this

and sought to build on the child’s own motivation and initiatives" and

"A concern about the child’s capacity to resist an ideology transmitted

through the school."

In his Political Justice he criticizes state sponsored schooling "on account of its obvious alliance with national government". For him the State "will not fail to employ it to strengthen its hands, and perpetuate its institutions.".

He thought "It is not true that our youth ought to be instructed to

venerate the constitution, however excellent; they should be instructed

to venerate truth; and the constitution only so far as it corresponded

with their independent deductions of truth.". A long work on the subject of education to consider is The Enquirer. Reflections On Education, Manners, And Literature. In A Series Of Essays.

Max Stirner

Max Stirner was a German philosopher linked mainly with the anarchist school of thought known as individualist anarchism who worked as a schoolteacher in a gymnasium for young girls. He examines the subject of education directly in his long essay The False Principle of our Education.

In it "we discern his persistent pursuit of the goal of individual

self-awareness and his insistence on the centering of everything around

the individual personality".

As such Stirner "in education, all of the given material has value only

in so far as children learn to do something with it, to use it".

In that essay he deals with the debates between realist and humanistic

educational commentators and sees that both "are concerned with the

learner as an object, someone to be acted upon rather than one

encouraged to move toward subjective self-realization and liberation"

and sees that "a knowledge which only burdens me as a belonging and a

possession, instead of having gone along with me completely so that the

free-moving ego, not encumbered by any dragging possessions, passes

through the world with a fresh spirit, such a knowledge then, which has

not become personal, furnishes a poor preparation for life".

He concludes this essay by saying that "the necessary decline of

non-voluntary learning and rise of the self-assured will which perfects

itself in the glorious sunlight of the free person may be expressed

somewhat as follows: knowledge must die and rise again as will and

create itself anew each day as a free person.".

Stirner thus saw education "is to be life and there, as outside of it,

the self-revelation of the individual is to be the task."

For him "pedagogy should not proceed any further towards civilizing,

but toward the development of free men, sovereign characters".

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist. "Where utopian projectors starting with Plato

entertained the idea of creating an ideal species through eugenics and

education and a set of universally valid institutions inculcating shared

identities, Warren wanted to dissolve such identities in a solution of

individual self-sovereignty. His educational experiments, for example,

possibly under the influence of the...Swiss educational theorist Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (via Robert Owen),

emphasized—as we would expect—the nurturing of the independence and the

conscience of individual children, not the inculcation of pre-conceived

values."

The classics and the late 19th century

Mikhail Bakunin

On "Equal Opportunity in Education" Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin

denounced what he saw as the social inequalities caused by the current

educational systems. He put this issue in this way "will it be feasible

for the working masses to know complete emancipation as long as the

education available to those masses continues to be inferior to that

bestowed upon the bourgeois, or, in more general terms, as long as there

exists any class, be it numerous or otherwise, which, by virtue of

birth, is entitled to a superior education and a more complete

instruction? Does not the question answer itself?..."

He also denounced that "Consequently while some study others must

labour so that they can produce what we need to live — not just

producing for their own needs, but also for those men who devote

themselves exclusively to intellectual pursuits.

As a solution to this Bakunin proposed that "Our answer to that is a

simple one: everyone must work and everyone must receive education...for

work's sake as much as for the sake of science, there must no longer be

this division into workers and scholars and henceforth there must be

only men. "

Peter Kropotkin

Russian anarcho-communist theorist Peter Kropotkin

suggested in "Brain Work and Manual Work" that "The masses of the

workmen do not receive more scientific education than their grandfathers

did; but they have been deprived of the education of even the small

workshop, while their boys and girls are driven into a mine, or a

factory, from the age of thirteen, and there they soon forget the little

they may have learned at school. As to the scientists, they despise

manual labour."

So for Kropotkin "We fully recognise the necessity of specialisation of

knowledge, but we maintain that specialisation must follow general

education, and that general education must be given in science and

handicraft alike. To the division of society into brainworkers and

manual workers we oppose the combination of both kinds of activities;

and instead of `technical education,' which means the maintenance of the

present division between brain work and manual work, we advocate the

éducation intégrale, or complete education, which means the

disappearance of that pernicious distinction."

The Early 20th century

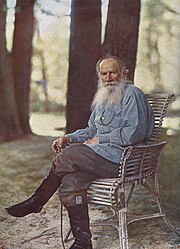

Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy, influential christian anarchist and anarcho pacifist theorist

The Russian christian anarchist and famous novelist Leo Tolstoy established a school for peasant children on his estate.

Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana and founded thirteen schools for

his serfs' children, based on the principles Tolstoy described in his

1862 essay "The School at Yasnaya Polyana".

Tolstoy's educational experiments were short-lived due to harassment by

the Tsarist secret police, but as a direct forerunner to A. S. Neill's Summerhill School, the school at Yasnaya Polyana can justifiably be claimed to be the first example of a coherent theory of democratic education.

Tolstoy differentiated between education and culture.

He wrote that "Education is the tendency of one man to make another

just like himself... Education is culture under restraint, culture is

free. [Education is] when the teaching is forced upon the pupil, and

when then instruction is exclusive, that is when only those subjects are

taught which the educator regards as necessary". For him "without compulsion, education was transformed into culture".

Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia and the Modern schools

Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia, Catalan anarchist pedagogue

In 1901, Catalan anarchist and free-thinker Francesc Ferrer established "modern" or progressive schools in Barcelona in defiance of an educational system controlled by the Catholic Church. The schools' stated goal was to "educate the working class

in a rational, secular and non-coercive setting". Fiercely

anti-clerical, Ferrer believed in "freedom in education", education free

from the authority of church and state. Murray Bookchin

wrote: "This period [1890s] was the heyday of libertarian schools and

pedagogical projects in all areas of the country where Anarchists

exercised some degree of influence. Perhaps the best-known effort in

this field was Francisco Ferrer's Modern School (Escuela Moderna), a

project which exercised a considerable influence on Catalan education

and on experimental techniques of teaching generally." La Escuela Moderna, and Ferrer's ideas generally, formed the inspiration for a series of Modern Schools in the United States,[15] Cuba, South America and London. The first of these was started in New York City in 1911. It also inspired the Italian newspaper Università popolare, founded in 1901.

Ferrer wrote an extensive work on education and on his educational experiments called The Origin and Ideals of the Modern School.

The Modern School movement in the United States

The NYC Modern School, ca. 1911–1912, Principal Will Durant and pupils. This photograph was the cover of the first issue of The Modern School magazine.

The Modern Schools, also called Ferrer Schools, were United States schools, established in the early twentieth century, that were modeled after the Escuela Moderna of Francesc Ferrer, the Catalan educator and anarchist. They were an important part of the anarchist, free schooling, socialist, and labor movements in the U.S., intended to educate the working-classes from a secular, class-conscious

perspective. The Modern Schools imparted day-time academic classes for

children, and night-time continuing-education lectures for adults.

The first, and most notable, of the Modern Schools was founded in

New York City, in 1911, two years after Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia's

execution for sedition in monarchist Spain on 18 October 1909. Commonly called the Ferrer Center, it was founded by notable anarchists — including Leonard Abbott, Alexander Berkman, Voltairine de Cleyre, and Emma Goldman — first meeting on St. Mark's Place, in Manhattan's Lower East Side, but twice moved elsewhere, first within lower Manhattan, then to Harlem. The Ferrer Center opened with only nine students, one being the son of Margaret Sanger, the contraceptives-rights activist. Starting in 1912, the school's principal was the philosopher Will Durant, who also taught there. Besides Berkman and Goldman, the Ferrer Center faculty included the Ashcan School painters Robert Henri and George Bellows, and its guest lecturers included writers and political activists such as Margaret Sanger, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair. Student Magda Schoenwetter, recalled that the school used Montessori methods and equipment, and emphasised academic freedom rather than fixed subjects, such as spelling and arithmetic. The Modern School magazine originally began as a newsletter for parents, when the school was in New York City, printed with the manual printing press

used in teaching printing as a profession. After moving to the Stelton

Colony, New Jersey, the magazine's content expanded to poetry, prose,

art, and libertarian education articles; the cover emblem and interior

graphics were designed by Rockwell Kent. Artists and writers, among them Hart Crane and Wallace Stevens, praised The Modern School as “the most beautifully printed magazine in existence.”

After the 4 July 1914 Lexington Avenue bombing,

the police investigated and several times raided the Ferrer Center and

other labor and anarchist organisations in New York City. Acknowledging the urban danger to their school, the organizers bought 68 acres (275,000 m²) in Piscataway Township, New Jersey, and moved there in 1914, becoming the center of the Stelton Colony. Moreover, beyond New York City, the Ferrer Colony and Modern School

was founded (ca. 1910–1915) as a Modern School-based community, that

endured some forty years. In 1933, James and Nellie Dick, who earlier

had been principals of the Stelton Modern School, founded the Modern

School in Lakewood, New Jersey, which survived the original Modern School, the Ferrer Center, becoming the final surviving such school, lasting until 1958.

Emma Goldman

In an essay entitled "The child and its enemies" Lithuanian-American anarcha-feminist Emma Goldman

manifested that "The child shows its individual tendencies in its

plays, in its questions, in its association with people and things. But

it has to struggle with everlasting external interference in its world

of thought and emotion. It must not express itself in harmony with its

nature, with its growing personality. It must become a thing, an object.

Its questions are met with narrow, conventional, ridiculous replies,

mostly based on falsehoods; and, when, with large, wondering, innocent

eyes, it wishes to behold the wonders of the world, those about it

quickly lock the windows and doors, and keep the delicate human plant in

a hothouse atmosphere, where it can neither breathe nor grow freely."

Goldman in the essay entitled "The Social Importance of the Modern

School" saw that "the school of today, no matter whether public,

private, or parochial...is for the child what the prison is for the

convict and the barracks for the soldier — a place where everything is

being used to break the will of the child, and then to pound, knead, and

shape it into a being utterly foreign to itself."

In this way "it will be necessary to realize that education of

children is not synonymous with herdlike drilling and training. If

education should really mean anything at all, it must insist upon the

free growth and development of the innate forces and tendencies of the

child. In this way alone can we hope for the free individual and

eventually also for a free community, which shall make interference and

coercion of human growth impossible."

Goldman in her essay on the Modern School also dealt with the issue of Sex education.

She denounced that "educators also know the evil and sinister results

of ignorance in sex matters. Yet, they have neither understanding nor

humanity enough to break down the wall which puritanism has built around

sex...If in childhood both man and woman were taught a beautiful

comradeship, it would neutralize the oversexed condition of both and

would help woman's emancipation much more than all the laws upon the

statute books and her right to vote."

Later 20th century and contemporary times

Experiments in Germany led to A. S. Neill founding what became Summerhill School in 1921. Summerhill is often cited as an example of anarchism in practice. British anarchists Stuart Christie and Albert Meltzer

manifested that "A.S. Neill is the modern pioneer of libertarian

education and of “hearts not heads in the school”. Although he has

denied being an anarchist, it would be hard to know how else to describe

his philosophy, though he is correct in recognising the difference

between revolution in philosophy and pedagogy, and the revolutionary

change of society. They are associated but not the same thing." However, although Summerhill and other free schools are radically libertarian, they differ in principle from those of Ferrer by not advocating an overtly political class struggle-approach.

Herbert Read

The English anarchist philosopher, art critic and poet, Herbert Read developed a strong interest in the subject of education and particularly in art education. Read's anarchism was influenced by William Godwin, Peter Kropotkin and Max Stirner.

Read "became deeply interested in children’s drawings and paintings

after having been invited to collect works for an exhibition of British

art that would tour allied and neutral countries during the Second World

War. As it was considered too risky to transport across the Atlantic

works of established importance to the national heritage, it was

proposed that children’s drawings and paintings should be sent instead.

Read, in making his collection, was unexpectedly moved by the expressive

power and emotional content of some of the younger artist’s works. The

experience prompted his special attention to their cultural value, and

his engagement of the theory of children’s creativity with seriousness

matching his devotion to the avant-garde. This work both changed

fundamentally his own life’s work throughout his remaining twenty-five

years and provided art education with a rationale of unprecedented

lucidity and persuasiveness. Key books and pamphlets resulted: Education through Art (Read, 1943); The Education of Free Men (Read, 1944); Culture and Education in a World Order (Read, 1948); The Grass Read, (1955); and Redemption of the Robot (1970)".

Read "elaborated a socio-cultural dimension of creative

education, offering the notion of greater international understanding

and cohesiveness rooted in principles of developing the fully balanced

personality through art education. Read argued in Education through Art

that "every child, is said to be a potential neurotic capable of being

saved from this prospect, if early, largely inborn, creative abilities

were not repressed by conventional Education. Everyone is an artist of

some kind whose special abilities, even if almost insignificant, must be

encouraged as contributing to an infinite richness of collective life.

Read’s newly expressed view of an essential ‘continuity’ of

child and adult creativity in everyone represented a synthesis' the two

opposed models of twentieth-century art education that had predominated

until this point...Read did not offer a curriculum but a theoretical

defence of the genuine and true. His claims for genuineness and truth

were based on the overwhelming evidence of characteristics revealed in

his study of child art...From 1946 until his death in 1968 he was

president of the Society for Education in Art (SEA), the renamed ATG, in

which capacity he had a platform for addressing UNESCO...On

the basis of such representation Read, with others, succeeded in

establishing the International Society for Education through Art (INSEA)

as an executive arm of UNESCO in 1954.

Paul Goodman

Paul Goodman was an important anarchist critic of contemporary educational systems as can be seen in his books Growing Up Absurd and Compulsory Mis-education.

Goodman believed that in contemporary societies "It is in the schools

and from the mass media, rather than at home or from their friends, that

the mass of our citizens in all classes learn that life is inevitably

routine, depersonalized, venally graded; that it is best to toe the mark

and shut up; that there is no place for spontaneity, open sexuality and

free spirit. Trained in the schools they go on to the same quality of

jobs, culture and politics. This is education, miseducation socializing

to the national norms and regimenting to the nation's "needs"

Goodman thought that a person's most valuable educational experiences

"occur outside the school. Participation in the activities of society

should be the chief means of learning. Instead of requiring students to

succumb to the theoretical drudgery of textbook learning, Goodman

recommends that education be transferred into factories, museums,

parks, department stores, etc, where the students can actively

participate in their education...The ideal schools would take the form

of small discussion groups of no more than twenty individuals. As has

been indicated, these groups would utilize any effective environment

that would be relevant to the interest of the group. Such education

would be necessarily non-compulsory, for any compulsion to attend places

authority in an external body disassociated from the needs and

aspirations of the students. Moreover, compulsion retards and impedes

the students' ability to learn."

As far as the current educational system Goodman thought that "The

basic intention behind the compulsory attendance laws is not only to

insure the socialization process but also to control the labour supply

quantitatively within an industrialized economy characterized by

unemployment and inflation. The public schools and universities have

become large holding tanks of potential workers."

Ivan Illich

The term deschooling was popularized by Ivan Illich,

who argued that the school as an institution is dysfunctional for

self-determined learning and serves the creation of a consumer society

instead.

Illich thought that "the dismantling of the public education system

would coincide with a pervasive abolition of all the suppressive

institutions of society".

Illich "charges public schooling with institutionalizing acceptable

moral and behavioral standards and with constitutionally violating the rights of young adults...IIlich

subscribes to Goodman's belief that most

of the useful education that people acquire is a by-product of work or

leisure and not of the school. Illich refers to this process as

"informal education". Only through this unrestricted and unregulated

form of learning can the individual

gain a sense of self-awareness and develop his creative capacity to its

fullest extent."

Illich thought that the main goals of an alternative education systems

should be "to provide access to available resources to all who want to

learn: to empower

all who want to share what they know; to find those who want to learn it

from them; to furnish all who want to present an issue to the public

with the opportunity to make their challenges known. The system of

learning webs is aimed at individual freedom and expression in education

by using society as the classroom. There would be reference services to

index items available for study in laboratories, theatres, airports,

libraries, etc.; skill exchanges which would permit people to list their

skills so that potential students could contact them; peer-matching,

which would communicate an individual's interest so that he or she could

find educational associates; reference services to educators at large,

which would be a central directory of professionals, para professionals

and freelancers.".

Colin Ward

English anarchist Colin Ward in his main theoretical publication Anarchy in Action

(1973) in a chapter called "Schools No Longer" "discusses the genealogy

of education and schooling, in particular examining the writings of Everett Reimer and Ivan Illich, and the beliefs of anarchist educator Paul Goodman. Many of Colin’s writings in the 1970s, in particular Streetwork: The Exploding School (1973, with Anthony Fyson), focused on learning practices and spaces outside of the school building. In introducing Streetwork,

Ward writes, “[this] is a book about ideas: ideas of the environment as

the educational resource, ideas of the enquiring school, the school

without walls…”. In the same year, Ward contributed to Education Without Schools

(edited by Peter Buckman) discussing ‘the role of the state’. He

argued that “one significant role of the state in the national education

systems of the world is to perpetuate social and economic injustice”".

In The Child in the City (1978), and later The Child in the Country

(1988), Ward "examined the everyday spaces of young people’s lives and

how they can negotiate and re-articulate the various environments they

inhabit. In his earlier text, the more famous of the two, Colin Ward

explores the creativity and uniqueness of children and how they

cultivate ‘the art of making the city work’. He argued that through

play, appropriation and imagination, children can counter adult-based

intentions and interpretations of the built environment. His later

text, The Child in the Country, inspired a number of social scientists,

notably geographer Chris Philo (1992), to call for more attention to be

paid to young people as a ‘hidden’ and marginalised group in society."

Bibliography

The Modern School magazine, Spring, 1920

- Archer, William. The Life, Trial, and Death of Francisco Ferrer. London: Chapman and Paul. 1911

- Avrich, Paul. The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States. AK Press, Jan 30, 2006

- Boyd, Carol. P. The Anarchists and education in Spain. (1868-1909). The Journal of Modern History. Vol. 48. No. 4. (Dec. 1976)

- Ferm, Elizabeth Byrne. Freedom in Education. New York: Lear Publishers. 1949

- Goodman, Paul. Compulsory Mis-Education. New York: Horizon. 1964

- Graubard, Allen. Free the Children: Radical Reform and the Free School Movement. New York: Pantheon. 1973

- Hemmings, Ray. Children’s Freedom: A. S. Neill and the Evolutions of the Summerhill Idea. London: Allen & Unwin. 1972

- Illich, Ivan. Deschooling Society. 1971. ISBN 0-06-012139-4.

- Jandric, Petar. "Wikipedia and education: anarchist perspectives and virtual practices." Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, vol.8. no.2

- Jensen, Derrick. Walking on Water: Reading, Writing, and Revolution, Chelsea Green, 2005, ISBN 978-1-931498-78-4

- Stirner, Max. "The False Principle of Our Education - or Humanism and Realism." . Rheinische Zeitung. April 1842

- Suissa, Judith. Anarchism and Education: a Philosophical Perspective. Routledge. New York. 2006

- Suissa, Judith. "Anarchy in the classroom". New Humanist. Volume 120. Issue 5 September/October 2005