Clarence Darrow

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 18, 1857 |

| Died | March 13, 1938 (aged 80) |

| Alma mater | Allegheny College University of Michigan |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

Clarence Seward Darrow (/ˈdæroʊ/; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of the American Civil Liberties Union, and a prominent advocate for Georgist economic reform.

Called a "sophisticated country lawyer", Darrow's wit and eloquence made him one of the most prominent attorneys and civil libertarians in the nation. He defended high-profile clients in many famous trials of the early 20th century, including teenage thrill killers Leopold and Loeb for murdering 14-year-old Robert "Bobby" Franks (1924); teacher John T. Scopes in the Scopes "Monkey" Trial (1925), in which he opposed statesman and orator William Jennings Bryan; and Ossian Sweet in a racially charged self-defense case (1926).

Early life

Clarence Darrow was born in the small town of Farmdale, Ohio, on April 18, 1857, the fifth son of Amirus and Emily Darrow (née Eddy). Both the Darrow and Eddy families had deep roots in colonial New England, and several of Darrow's ancestors served in the American Revolution. Darrow's father was an ardent abolitionist and a proud iconoclast and religious freethinker. He was known throughout the town as the "village infidel". Emily Darrow was an early supporter of female suffrage and a women's rights advocate.

The young Clarence attended Allegheny College and the University of Michigan Law School, but did not graduate from either institution. He attended Allegheny College for only one year before the Panic of 1873

struck, and Darrow was determined not to be a financial burden to his

father any longer. Over the next three years he taught in the winter at

the district school in a country community. While teaching, Darrow

started to study the law

on his own, and by the end of his third year of teaching, his family

urged him to enter the law department at Ann Arbor. Darrow only studied

there a year when he decided that it would be much more cost-effective

to work and study in an actual law office. When he felt that he was

ready, he took the Ohio bar exam and passed. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1878. The Clarence Darrow Octagon House, his childhood home in Kinsman, contains a memorial to him.

Marriages and child

Darrow

married Jessie Ohl in April 1880. They had one child, Paul Edward

Darrow, in 1883. They were divorced in 1897. Darrow later married Ruby

Hammerstrom, a journalist 16 years his junior, in 1903. They had no

children.

Legal career

Darrow opened his first little law office in Andover, Ohio,

a small farming town just ten miles from Kinsman. Having little to no

experience, he started off slowly and gradually built up his career by

dealing with the everyday complaints and problems of a farming

community. After two years Darrow felt he was ready to take on new and

different cases and moved his practice to Ashtabula, Ohio, which had a population of 5,000 people and was the largest city in the county. There he became involved in Democratic Party politics and served as the town counsel.

In 1880, he married Jessie Ohl, and eight years later he moved to

Chicago with his wife and young son, Paul. He did not have much

business when he first moved to Chicago, and spent as little as

possible. He joined the Henry George Club and made some friends and

connections in the city. Being part of the club also gave him an

opportunity to speak for the Democratic Party on the upcoming election.

He slowly made a name for himself through these speeches, eventually

earning the standing to speak in whatever hall he liked. He was offered

work as an attorney for the city of Chicago. Darrow worked in the city

law department for two years when he resigned and took a position as a

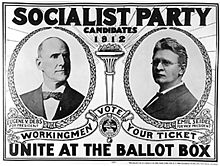

lawyer at the Chicago and North-Western Railway Company. In 1894, Darrow represented Eugene V. Debs, the leader of the American Railway Union, who was prosecuted by the federal government for leading the Pullman Strike

of 1894. Darrow severed his ties with the railroad to represent Debs,

making a financial sacrifice. He saved Debs in one trial but could not

keep him from being jailed in another.

Also in 1894, Darrow took on the first murder case of his career, defending Patrick Eugene Prendergast, the "mentally deranged drifter" who had confessed to murdering Chicago mayor Carter Harrison, Sr.

Darrow's "insanity defense" failed and Prendergast was executed that

same year. Among fifty defenses in murder cases throughout the whole of

Darrow's career, the Prendergast case would prove to be the only one

resulting in an execution, though Darrow did not join the defense team

until after Prendergast's conviction and sentence, in an effort to spare

him the noose.

From corporate lawyer to labor lawyer

Darrow soon became one of America's leading labor attorneys. He helped organize the Populist Party in Illinois and then ran for U.S. Congress as a Democrat in 1895 but lost to Hugh R. Belknap. In 1897, his marriage to Jessie Ohl ended in divorce. He joined the Anti-Imperialist League in 1898 in opposition to the U.S. annexation of the Philippines. He represented the woodworkers of Wisconsin in a notable case in Oshkosh in 1898 and the United Mine Workers in Pennsylvania in the great anthracite coal strike of 1902.

He flirted with the idea of running for mayor of Chicago in 1903 but

ultimately decided against it. The following year, in July, Darrow

married Ruby Hammerstrom, a young Chicago journalist. His former mentor, Governor John Peter Altgeld, joined Darrow's firm following his Chicago mayoral electoral defeat in 1899 and worked with Darrow until his death in 1902.

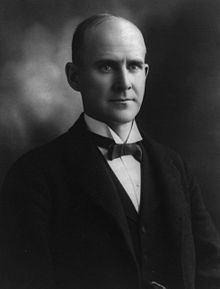

Clarence Darrow in 1902

From 1906 to 1908, Darrow represented the Western Federation of Miners leaders William "Big Bill" Haywood, Charles Moyer, and George Pettibone when they were arrested and charged with conspiring to murder former Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg in 1905. Haywood and Pettibone were found not guilty in separate trials, and the charges against Moyer were then dropped.

In 1911, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) called on Darrow to defend the McNamara brothers, John and James, who were charged in the Los Angeles Times bombing on October 1, 1910, during the bitter struggle over the open shop

in Southern California. The bomb had been placed in an alley behind the

building, and although the explosion itself did not bring the building

down, it ignited nearby ink barrels and natural gas main lines. In the

ensuing fire, 20 people were killed. The AFL appealed to local, state,

regional and national unions to donate 25 cents per capita to the

defense fund, and set up defense committees in larger cities throughout

the nation to accept donations.

In the weeks before the jury was seated, Darrow became

increasingly concerned about the outcome of the trial and began

negotiations for a plea bargain to spare the defendants' lives. During

the weekend of November 19–20, 1911, he discussed with pro-labor

journalist Lincoln Steffens and newspaper publisher E.W. Scripps the possibility of reaching out to the Times

about the terms of a plea agreement. The prosecution had demands of its

own, however, including an admission of guilt in open court and longer

sentences than the defense proposed.

The defense's position weakened when, on November 28, Darrow was

accused of orchestrating to bribe a prospective juror. The juror

reported the offer to police, who set up a sting and observed the

defense team's chief investigator, Bert Franklin, delivering $4,000 to

the juror two blocks away from Darrow's office. After making payment,

Franklin walked one block in the direction of Darrow's office before

being arrested right in front of Darrow himself, who had just walked to

that very intersection after receiving a phone call in his office. With

Darrow himself on the verge of being discredited, the defense's hope for

a simple plea agreement ended.

On December 1, 1911, the McNamara brothers changed their pleas to

guilty, in open court. The plea bargain Darrow helped arrange earned

John fifteen years and James life imprisonment. Despite sparing the

brothers the death penalty, Darrow was accused by many in organized

labor of selling the movement out.

Two months later, Darrow was charged with two counts of

attempting to bribe jurors in both cases. He faced two lengthy trials.

In the first, defended by Earl Rogers, he was acquitted. Rogers became ill during the second trial and rarely came to court. Darrow served as his own attorney for the remainder of the trial, which ended with a hung jury.

A deal was struck in which the district attorney agreed not to retry

Darrow if he promised not to practice law again in California. Darrow's early biographers, Irving Stone

and Arthur and Lila Weinberg, asserted that he was not involved in the

bribery conspiracy, but more recently, Geoffrey Cowan and John A.

Farrell, with the help of new evidence, concluded that he almost

certainly was. In the biography of Earl Rogers by his daughter Adela,

she wrote: "I never had any doubts, even before one of my father's

private conversations with Darrow included an admission of guilt to his

lawyer."

From labor lawyer to criminal lawyer

Darrow in 1913

As a consequence of the bribery charges, most labor unions dropped

Darrow from their list of preferred attorneys. This effectively put

Darrow out of business as a labor lawyer, and he switched to civil and

criminal cases. He took the latter because he had become convinced that

the criminal justice system could ruin people's lives if they were not

adequately represented.

Throughout his career, Darrow devoted himself to opposing the death penalty, which he felt to be in conflict with humanitarian

progress. In more than 100 cases, Darrow only lost one murder case in

Chicago. He became renowned for moving juries and even judges to tears

with his eloquence. Darrow had a keen intellect often hidden by his

rumpled, unassuming appearance.

A July 23, 1915, article in the Chicago Tribune describes Darrow's effort on behalf of J.H. Fox, an Evanston, Illinois,

landlord, to have Mary S. Brazelton committed to an insane asylum

against the wishes of her family. Fox alleged that Brazelton owed him

rent money, although other residents of Fox's boarding house testified

to her sanity.

National renown

Leopold and Loeb

In the summer of 1924, Darrow took on the case of Nathan Leopold Jr. and Richard Loeb, the teenage sons of two wealthy Chicago families who were accused of kidnapping and killing Bobby Franks, a 14-year-old boy, from their stylish southside Kenwood neighborhood. Leopold was a law student at the University of Chicago about to transfer to Harvard Law School,

and Loeb was the youngest graduate ever from the University of

Michigan; they were 18 and 17, respectively, when they were arrested.

When asked why they committed the crime, Leopold told his captors: "The

thing that prompted Dick to want to do this thing and prompted me to

want to do this thing was a sort of pure love of excitement... the

imaginary love of thrills, doing something different... the satisfaction

and the ego of putting something over."

Chicago newspapers labeled the case the "Trial of the Century"

and Americans around the country wondered what could drive the two

young men, blessed with everything their society could offer, to commit

such a depraved act. The killers had been arrested after a passing

workman spotted the victim's body in an isolated nature preserve near

the Indiana border just half a day after it was hidden, before they

could collect a $10,000 ransom. Nearby were Leopold's eyeglasses with

their distinctive, traceable frames, which he had dropped at the scene.

Leopold and Loeb made full confessions and took police on a hunt

around Chicago to collect the evidence that would be used against them.

The state's attorney told the press that he had a "hanging case" for

sure. Darrow stunned the prosecution when he had his clients plead

guilty in order to avoid a vengeance-minded jury and place the case

before a judge. The trial, then, was actually a long sentencing hearing

in which Darrow contended, with the help of expert testimony, that

Leopold and Loeb were mentally diseased.

Darrow's closing argument lasted 12 hours. He repeatedly stressed

the ages of the "boys" (before the Vietnam War, the age of majority was

21) and noted that "never had there been a case in Chicago where on a

plea of guilty a boy under 21 had been sentenced to death." His plea was

designed to soften the heart of Judge John Caverly, but also to mold

public opinion, so that Caverly could follow precedent without too huge

an uproar. Darrow succeeded. Caverly sentenced Leopold and Loeb to life

in prison plus 99 years. Darrow's closing argument was published in

several editions in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and was reissued at

the time of his death.

The Leopold and Loeb case raised, in a well-publicized trial,

Darrow's lifelong contention that psychological, physical, and

environmental influences—not a conscious choice between right and

wrong—control human behavior. Darrow's psychiatric expert witnesses

testified that both boys "were decidedly deficient in emotion". Darrow

later argued that emotion is necessary for the decisions that people

make. When someone tries to go against a certain law or custom that is

forbidden, he wrote, he should feel a sense of revulsion. As neither

Leopold nor Loeb had a working emotional system, they did not feel

revolted.

During the trial, the newspapers claimed that Darrow was

presenting a "million dollar defense" for the two wealthy families. Many

ordinary Americans were angered at his apparent greed. He had the

families issue a statement insisting that there would be no large legal

fees and that his fees would be determined by a committee composed of

officers from the Chicago Bar Association.

After trial, Darrow suggested $200,000 would be reasonable. After

lengthy negotiations with the defendants' families, he ended up getting

some $70,000 in gross fees, which, after expenses and taxes, netted

Darrow $30,000, worth over $375,000 in 2016.

Scopes Trial

Clarence Darrow circa 1925

In 1925, Darrow defended John T. Scopes in the State of Tennessee v. Scopes trial. It has often been called the "Scopes Monkey Trial," a title popularized by author and journalist H.L. Mencken. The trial, which was deliberately staged to bring publicity to the issue at hand, pitted Darrow against William Jennings Bryan in a court case that tested Tennessee's Butler Act, which had been passed on March 21, 1925. The act forbade the teaching of "the Evolution Theory"

in any state-funded educational establishment. More broadly, it

outlawed in state-funded schools (including universities) the teaching

of "any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals."

During the trial, Darrow requested that Bryan be called to the stand as an expert witness on the Bible. Over the other prosecutor's objection, Bryan agreed. Popular media at the time portrayed the following exchange as the deciding factor that turned public opinion against Bryan in the trial:

Darrow: "You have given considerable study to the Bible, haven't you, Mr. Bryan?"

Bryan: "Yes, sir; I have tried to.... But, of course, I have studied it more as I have become older than when I was a boy." Darrow: "Do you claim then that everything in the Bible should be literally interpreted?"

Bryan: "I believe that everything in the Bible should be accepted as it is given there; some of the Bible is given illustratively. For instance: 'Ye are the salt of the earth.' I would not insist that man was actually salt, or that he had flesh of salt, but it is used in the sense of salt as saving God's people."

After about two hours, Judge John T. Raulston

cut the questioning short and on the following morning ordered that the

whole session (which in any case the jury had not witnessed) be

expunged from the record, ruling that the testimony had no bearing on

whether Scopes was guilty of teaching evolution. Scopes was found guilty

and ordered to pay the minimum fine of $100.

A year later, the Tennessee Supreme Court

reversed the decision of the Dayton court on a procedural

technicality—not on constitutional grounds, as Darrow had hoped.

According to the court, the fine should have been set by the jury, not

Raulston. Rather than send the case back for further action, however,

the Tennessee Supreme Court dismissed the case. The court commented,

"Nothing is to be gained by prolonging the life of this bizarre case."

The event led to a change in public sentiment and an increased

discourse on the creation claims of religious teachers versus those of

secular scientists — i.e., creationism compared to evolutionism — that still exists. It also became popularized in a play based loosely on the trial, Inherit the Wind, which has been adapted several times on film and television.

Ossian Sweet

On September 9, 1925, a white

mob in Detroit attempted to drive a black family out of the home they

had purchased in a white neighborhood. During the struggle, a white man

was killed, and the eleven black men in the house were later arrested

and charged with murder. Ossian Sweet, a doctor, and three members of his family were brought to trial, and after an initial deadlock, Darrow argued to the all-white jury:

"I insist that there is nothing but prejudice in this case; that if it

was reversed and eleven white men had shot and killed a black man while

protecting their home and their lives against a mob of blacks, nobody

would have dreamed of having them indicted. They would have been given

medals instead...."

Following a mistrial, it was agreed that each of the eleven

defendants would be tried individually. Darrow, alongside Thomas Chawke,

would first defend Ossian's brother Henry, who had confessed to firing

the shot on Garland Street. Henry was found not guilty on grounds of self-defense, and the prosecution determined to drop the charges on the remaining ten. The trials were presided over by Frank Murphy, who went on to become Governor of Michigan and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Darrow's closing statement, which lasted over seven hours, is seen as a landmark in the Civil Rights movement and was included in the book Speeches that Changed the World

(given the name "I Believe in the Law of Love"). The two closing

arguments of Clarence Darrow, from the first and second trials, show how

he learned from the first trial and reshaped his remarks.

Massie Trial

The

Scopes Trial and the Sweet trial were the last big cases that Darrow

took on before he retired from full-time practice at the age of 68. He

still took on a few cases such as the 1932 Massie Trial in Hawaii.

In his last headline-making case, the Massie Trial, Darrow, devastated by the Great Depression, was hired by Eva Stotesbury, the wife of Darrow's old family friend Edward T. Stotesbury, to come to the defense of Grace Fortescue, Edward J. Lord, Deacon Jones, and Thomas Massie, Fortescue's son-in-law, who were accused of murdering Joseph Kahahawai. Kahahawai had been accused, along with four other men, of raping and beating Thalia Massie,

Thomas's wife and Fortescue's daughter; the resulting 1931 case ended

in a hung jury (though the charges were later dropped and repeated

investigation has shown them to be innocent). Enraged, Fortescue and

Massie then orchestrated the murder of Kahahawai in order to extract a

confession and were caught by police officers while transporting his

dead body.

Darrow entered the racially charged atmosphere as the lawyer for the defendants. Darrow reconstructed the case as a justified honor killing by Thomas Massie. Considered by The New York Times

to be one of Darrow's three most compelling trials (along with the

Scopes Trial and the Leopold and Loeb case), the case captivated the

nation and most of white America strongly supported the honor killing

defense. In fact, the final defense arguments were transmitted to the

mainland through a special radio hookup. In the end, the jury came back

with a unanimous verdict of guilty, but on the lesser crime of

manslaughter.

As to Darrow's closing, one juror commented, "[h]e talked to us like a

bunch of farmers. That stuff may go over big in the Middle West, but not

here." Governor Lawrence Judd later commuted the sentences to one hour in his office. Years later Deacon admitted to shooting Kahahawai; Massie was found "not Guilty" in a posthumous trial.

Religious beliefs

"Why I Am An Agnostic"

As

part of a public symposium on belief held in Columbus, Ohio, Darrow

delivered a speech, later titled "Why I Am An Agnostic", on agnosticism, skepticism, belief, and religion. In the speech, Darrow thoroughly discussed the meaning of being an agnostic and questioned the doctrines of Christianity and the Bible.

He concluded that "the fear of God is not the beginning of wisdom. The

fear of God is the death of wisdom. Skepticism and doubt lead to study

and investigation, and investigation is the beginning of wisdom."

Mecca Temple Debate

In January 1931 Darrow had a debate with English writer G. K. Chesterton

during the latter's second trip to America. This was held at New York

City's Mecca Temple. The topic was "Will the World Return to Religion?".

At the end of the debate those in the hall were asked to vote for the

man they thought had won the debate. Darrow received 1,022 votes while

Chesterton received 2,359 votes. There is no known transcript of what

was said except for third party accounts published later on. The

earliest of these was that of February 4, 1931, issue of The Nation with an article written by Henry Hazlitt.

Position on eugenics

In the edition of November 18, 1915 of The Washington Post,

Darrow stated: “Chloroform unfit children. Show them the same mercy

that is shown beasts that are no longer fit to live.” However, Darrow

was also critical of some eugenics advocates.

By the 1920s, the eugenics movement was very powerful and Darrow was a

pointed critic of that movement. In the years immediately before the

Supreme Court of the United States would endorse eugenics through Buck v. Bell (1927),

Darrow wrote multiple essays criticizing the illogic of the

eugenicists, especially the confirmation bias in eugenicist arguments. In a 1925 essay, “The Edwardses and the Jukeses,” he imitated the

eugenicists’ tracking of pedigrees as a way to demonstrate that their

retrospective centuries-long family tree studies were omitting literally

thousands of relatives whose lives did not support the researchers’

preconceptions. Eugenicist arguments about the eminent Edwards family

(of the theologian Jonathan Edwards) ignored that family’s mediocre

relatives, and even ignored some immediately related murderers.

Eugenicist arguments about the Jukes family did just the opposite,

leaving ignored or untraced many functional and law-abiding relatives. In Darrow’s subsequent essay, “The Eugenics Cult” (1926), he attacked the reasoning of eugenicists.

“On the basis of what biological principles, and by what psychological

hocus-pocus [Dr. William McDougall] reaches the conclusion that the

ability to read intelligently denotes a good germ-plasm and desirable

citizens I cannot say,” he wrote.

Darrow also criticized the idea that humanity even knows what qualities

it would take to make humanity “better,” and compared humanity’s

biology experiments unfavorably to those of Nature.

Death

Darrow died on March 13, 1938, of pulmonary heart disease.

Legacy

Today,

Clarence Darrow is remembered for his reputation as a fierce litigator

who, in many cases, championed the cause of the underdog; because of

this, he is generally regarded as one of the greatest criminal defense

lawyers in American history.

Henry Drummond (left), a fictionalized version of Clarence Darrow, as portrayed by Spencer Tracy in Inherit the Wind.

According to legend, before he died, Darrow declared that if there was an afterlife, he would return on the small bridge (now known as the Clarence Darrow Memorial Bridge) located just south of the Museum of Science and Industry in Hyde Park, Chicago

on the date of his death. Darrow was skeptical of a belief in life

after death (he is reported to have said: "Every man knows when his life

began... If I did not exist in the past, why should I, or could I,

exist in the future?") but he made this promise to dissuade mediums from charging people money to "talk" to his spirit. People still gather on the bridge in the hopes of seeing his ghost.

Plays

- Darrow, a full-length one-man play created after his death, featuring Darrow's reminiscences about his career. Originated by Henry Fonda, many actors (including Leslie Nielsen and David Canary) have since taken on the role of Darrow in this play, which was adapted as Darrow, a film starring Kevin Spacey and released by American Playhouse in 1991.

- Inherit the Wind, a play (later adapted to the screen) which is a broadly fictionalized account of the Scopes Trial. Though the authors note that the 1925 trial was "clearly the genesis" of their play, they insist that the characters had "life and language of their own." They also mention that the issues raised in the play "have acquired new dimension and meaning", a possible reference to the political controversies of the 1950s. Still, they finish their foreword by inviting a more universal reading of the play: "It might have been yesterday. It could be tomorrow." Spencer Tracy played the Darrow character ("Henry Drummond") in the film, and Jason Robards plays him in a TV remake in 1988.

- Malice Aforethought: The Sweet Trials is a play written by Arthur Beer, based on the trials of Ossian and Henry Sweet, and derived from Kevin Boyle's Arc of Justice.[42]

- My Name is Ossian Sweet, a docudrama written by Gordon C. Bennett, based on the Sweet trials in which the black family was defended by Darrow against a charge of murder in Detroit 1925. Published (2011) at HeartlandPlays.com.

- Clarence Darrow by David W. Rintels, where Kevin Spacey again portrayed Darrow in this one-man performance in 2014 and 2015.

- Clarence Darrow Tonight! written and performed by Laurence Luckinbill, debuted at The Ensemble Theater in NYC and performed throughout the country, including at President Bill Clinton's second inaugural in 1996. Winner of the 1996 Silver Gavel Award for Theater, given by the American Bar Association.

- During a police interrogation at the police station in the 1949 movie Holiday Affair, the character, Connie Ennis (Janet Leigh) said to the lieutenant (Harry Morgan), "Your honor, I think I can clear this all up." The lieutenant said, "Go ahead, if Clarence Darrow here doesn't have any objections." He was referring to her fiancé in the movie Carl Davis, played by Wendell Corey.

Film and television

- Compulsion, 1959 film. Fictionalized account of the Leopold and Loeb trial. Orson Welles played the role of the defense attorney, based on Darrow.

- Alleged, starring Brian Dennehy and Fred Thompson

- The episode, "Defendant: Clarence Darrow" (January 13, 1963), with Tol Avery playing Darrow, in the CBS anthology series, GE True, hosted by Jack Webb. In the storyline, Darrow is charged in 1912 with attempted bribery of a juror. He is defended by Earl Rogers, played by Robert Vaughn. Darrow and Rogers argue passionately over legal procedures.[45]

- Darrow is mentioned in the sixth season of Mad Men (episode 11: "Favors")

- Darrow is mentioned in the third season of Better Call Saul (episode 6: "Off Brand")

- Darrow is mentioned by Max Durocher (Jamie Foxx) in Collateral, 2004 film.

Publications

Non-fiction

- Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned by John A. Farrell, published by Doubleday in June 2011; includes new material opened to the public in June 2010 by the University of Minnesota Law Library through the Clarence Darrow Digital Collection

- The Angel of Darkness, with Darrow as a main character in the fictional Caleb Carr novel

- Arc of Justice (Owl Books, 2004) by Kevin Boyle; in-depth look at the Ossian Sweet trial

- Clarence Darrow for the Defense, a biography by historical novelist Irving Stone

- Compulsion (1956), Darrow was the inspiration for the character of Jonathan Wilk in the novel, a thinly fictionalized account of the Leopold and Loeb case. In 1959, the novel was adapted into a film of the same name, starring Orson Welles as Wilk. Welles, whose 3.day closing Address to the Judge on a guilty plea for mercy is abbreviated to the longest monologue ever committed to film at that time, shared the Best Actor award with co-stars Bradford Dillman and Dean Stockwell at that year's Cannes Film Festival.

- The People v. Clarence Darrow (ISBN 978-0-8129-2179-3) by Geoffrey Cowan; the history of the California criminal case against Darrow for attempting to bribe a juror while defending the McNamara brothers, two labor organizers accused of planting a bomb which destroyed the printing plant of the Los Angeles Times and killed 21 workers.

- "Is Religion Necessary" (Haldeman-Julius Publications); a transcript of the debate between Clarence Darrow and Rev. Robert MacGovern, 1931.

Fiction

- Damned In Paradise, a Nate Heller novel by Max Allan Collins features a fictionalized account of the Massie Trial.

Other

- The Clarence Darrow Memorial Bridge is located in Chicago, just south of the Museum of Science & Industry. The Clarence Darrow Commemorative Committee holds an annual event to honor Darrow's life and work.

- The complete collection of Clarence Darrow's personal papers is housed at the University of Minnesota Libraries.

- Darrow is mentioned in "The Gift", a 1967 song by Lou Reed as performed by The Velvet Underground on their 1968 album White Light/White Heat.

- The chapter of Phi Alpha Delta Law Fraternity, International located at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law is named the Clarence Darrow Chapter.

- A statue of Darrow stands outside the Rhea County Courthouse in Dayton Tennessee, site of the 1925 Scopes Trial. The statue was erected in July 14, 2017, and stands just a few feet away from a statue of Darrow's Scopes Trial opponent, William Jennings Bryan, erected in 2005.

- Darrow was reported to have distracted juries during the closing arguments of his opponents with a cigar trick. He allegedly inserted a thin piano wire into his cigar, which he lit up in the courtroom, to prevent the cigar ash from falling. The jury was reportedly distracted by the fact that the ashes, held together by the wire, never fell from Darrow's cigar.

Books by Darrow

A volume of Darrow's boyhood reminiscences, entitled Farmington, was published in Chicago in 1903 by McClurg and Company.

Darrow shared offices with Edgar Lee Masters, who achieved more fame for his poetry, in particular, the Spoon River Anthology, than for his advocacy.

The papers of Clarence Darrow are located at the Library of Congress and the University of Minnesota Libraries. The Riesenfeld Rare Books Research Center of the University of Minnesota Law School

has the largest collection of Clarence Darrow material including

personal letters to and from Darrow. Many of these letters and other

material are available on the U of M's Clarence Darrow Digital

Collection website.

List of books

- An Eye for an Eye

- Crime: Its Cause and Treatment

- Persian Pearl

- The Story of My Life

- Farmington

- Resist Not Evil

- Marx vs Tolstoy

- Closing Arguments on Religion, Law and Society

- The Myth of the Soul