Human intelligence is the intellectual prowess of humans, which is marked by complex cognitive feats and high levels of motivation and self-awareness. Through their intelligence, humans possess the cognitive abilities to learn, form concepts, understand, apply logic, and reason, including the capacities to recognize patterns, comprehend ideas, plan, solve problems, make decisions, retain information, and use language to communicate.

Correlates

As a construct and measured by intelligence tests, intelligence is considered to be one of the most useful concepts used in psychology,

because it correlates with lots of relevant variables, for instance the

probability of suffering an accident, earning a higher salary, and

more.

- Education

According to a 2018 metastudy

of educational effects on intelligence, education appears to be the

"most consistent, robust, and durable method" known for raising

intelligence.

- Myopia

A number of studies have shown a correlation between IQ and myopia.

Some suggest that the reason for the correlation is environmental,

whereby intelligent people are more likely to damage their eyesight with

prolonged reading, while others contend that a genetic link exists.

- Aging

There is evidence that aging causes decline in cognitive functions.

In one cross-sectional study, various cognitive functions measured

declines by about 0.8 in z-score from age 20 to age 50, the cognitive

functions included speed of processing, working memory and long term

memory.

Theories

Relevance of IQ tests

In psychology, human intelligence is commonly assessed by IQ

scores, determined by IQ tests. However, there are critics of IQ who do

not dispute the stability of IQ test scores, or the fact that they

predict certain forms of achievement rather effectively. They do argue,

however, that to base a concept of intelligence on IQ test scores alone

is to ignore many important aspects of mental ability.

On the other hand, Linda S. Gottfredson (2006) has argued that the results of thousands of studies support the importance of IQ for school and job performance

(see also the work of Schmidt & Hunter, 2004). She says that IQ

also predicts or correlates with numerous other life outcomes. In

contrast, empirical support for non-g intelligences is lacking or very poor.

Theory of multiple intelligences

Howard Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences is based on studies not only of normal children and adults, but also of gifted individuals (including so-called "savants"), of persons who have suffered brain damage, of experts and virtuosos,

and of individuals from diverse cultures. Gardner breaks intelligence

down into at least a number of different components. In the first

edition of his book Frames of Mind (1983), he described seven distinct types of intelligence—logical-mathematical, linguistic, spatial, musical, kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal.

In a second edition of this book, he added two more types of

intelligence—naturalist and existential intelligences. He argues that psychometric (IQ) tests address only linguistic and logical plus some aspects of spatial intelligence.

A major criticism of Gardner's theory is that it has never been tested,

or subjected to peer review, by Gardner or anyone else, and indeed that

it is unfalsifiable.

Others (e.g. Locke, 2005) have suggested that recognizing many specific

forms of intelligence (specific aptitude theory) implies a

political—rather than scientific—agenda, intended to appreciate the

uniqueness in all individuals, rather than recognizing potentially true

and meaningful differences in individual capacities. Schmidt and Hunter

(2004) suggest that the predictive validity of specific aptitudes over

and above that of general mental ability, or "g", has not received

empirical support. On the other hand, Jerome Bruner

agreed with Gardner that the intelligences were "useful fictions," and

went on to state that "his approach is so far beyond the data-crunching

of mental testers that it deserves to be cheered."

Howard Gardner describes his first seven intelligences as follows:

- Linguistic intelligence: People high in linguistic intelligence have an affinity for words, both spoken and written.

- Logical-mathematical intelligence: It implies logical and mathematical abilities.

- Spatial intelligence: The ability to form a mental model of a spatial world and to be able to maneuver and operate using that model.

- Musical intelligence: Those with musical intelligence have excellent pitch, and may even be absolute pitch.

- Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence: The ability to solve problems or to fashion products using one's whole body, or parts of the body. Gifted people in this intelligence may be good dancers, athletes, surgeons, craftspeople, and others.

- Interpersonal intelligence: The ability to see things from the perspective of others, or to understand people in the sense of empathy. Strong interpersonal intelligence would be an asset in those who are teachers, politicians, clinicians, religious leaders, etc.

- Intrapersonal intelligence: It is a capacity to form an accurate, veridical model of oneself and to be able to use that model to operate effectively in life.

Triarchic theory of intelligence

Robert Sternberg proposed the triarchic theory of intelligence

to provide a more comprehensive description of intellectual competence

than traditional differential or cognitive theories of human ability.

The triarchic theory describes three fundamental aspects of

intelligence. Analytic intelligence comprises the mental processes

through which intelligence is expressed. Creative intelligence is

necessary when an individual is confronted with a challenge that is

nearly, but not entirely, novel or when an individual is engaged in

automatizing the performance of a task. Practical intelligence is bound

in a sociocultural milieu and involves adaptation to, selection of, and

shaping of the environment to maximize fit in the context. The triarchic

theory does not argue against the validity of a general intelligence

factor; instead, the theory posits that general intelligence is part of

analytic intelligence, and only by considering all three aspects of

intelligence can the full range of intellectual functioning be fully

understood.

More recently, the triarchic theory has been updated and renamed as the Theory of Successful Intelligence by Sternberg. Intelligence is now defined as an individual's assessment of success in life by the individual's own (idiographic)

standards and within the individual's sociocultural context. Success is

achieved by using combinations of analytical, creative, and practical

intelligence. The three aspects of intelligence are referred to as

processing skills. The processing skills are applied to the pursuit of

success through what were the three elements of practical intelligence:

adapting to, shaping of, and selecting of one's environments. The

mechanisms that employ the processing skills to achieve success include

utilizing one's strengths and compensating or correcting for one's

weaknesses.

Sternberg's theories and research on intelligence remain contentious within the scientific community.

PASS theory of intelligence

Based on A. R. Luria's (1966) seminal work on the modularization of brain function, and supported by decades of neuroimaging research, the PASS Theory of Intelligence

proposes that cognition is organized in three systems and four

processes. The first process is the Planning, which involves executive

functions responsible for controlling and organizing behavior, selecting

and constructing strategies, and monitoring performance. The second is

the Attention process, which is responsible for maintaining arousal

levels and alertness, and ensuring focus on relevant stimuli. The next

two are called Simultaneous and Successive processing and they involve

encoding, transforming, and retaining information. Simultaneous

processing is engaged when the relationship between items and their

integration into whole units of information is required. Examples of

this include recognizing figures, such as a triangle within a circle vs.

a circle within a triangle, or the difference between 'he had a shower

before breakfast' and 'he had breakfast before a shower.' Successive

processing is required for organizing separate items in a sequence such

as remembering a sequence of words or actions exactly in the order in

which they had just been presented. These four processes are functions

of four areas of the brain. Planning is broadly located in the front

part of our brains, the frontal lobe. Attention and arousal are combined

functions of the frontal lobe and the lower parts of the cortex,

although the parietal lobes are also involved in attention as well.

Simultaneous processing and Successive processing occur in the posterior

region or the back of the brain. Simultaneous processing is broadly

associated with the occipital and the parietal lobes while Successive

processing is broadly associated with the frontal-temporal lobes. The

PASS (Planning/Attention/Simultaneous/Successive) theory is heavily

indebted to both Luria (1966, 1973), and studies in cognitive psychology involved in promoting a better look at intelligence.

Piaget's theory and Neo-Piagetian theories

In Piaget's theory of cognitive development

the focus is not on mental abilities but rather on a child's mental

models of the world. As a child develops, increasingly more accurate

models of the world are developed which enable the child to interact

with the world better. One example being object permanence where the child develops a model where objects continue to exist even when they cannot be seen, heard, or touched.

Piaget's theory described four main stages and many sub-stages in the development. These four main stages are:

- sensory motor stage (birth-2yrs);

- pre-operational stage (2yrs-7rs);

- concrete operational stage (7rs-11yrs); and

- formal operations stage (11yrs-16yrs)

Degree of progress through these stages are correlated, but not identical with psychometric IQ. Piaget conceptualizes intelligence as an activity more than a capacity.

One of Piaget's most famous studies focused purely on the

discriminative abilities of children between the ages of two and a half

years old, and four and a half years old. He began the study by taking

children of different ages and placing two lines of sweets, one with the

sweets in a line spread further apart, and one with the same number of

sweets in a line placed more closely together. He found that, "Children

between 2 years, 6 months old and 3 years, 2 months old correctly

discriminate the relative number of objects in two rows; between 3

years, 2 months and 4 years, 6 months they indicate a longer row with

fewer objects to have "more"; after 4 years, 6 months they again

discriminate correctly".

Initially younger children were not studied, because if at the age of

four years a child could not conserve quantity, then a younger child

presumably could not either. The results show however that children that

are younger than three years and two months have quantity conservation,

but as they get older they lose this quality, and do not recover it

until four and a half years old. This attribute may be lost temporarily

because of an overdependence on perceptual strategies, which correlates

more candy with a longer line of candy, or because of the inability for a

four-year-old to reverse situations.

By the end of this experiment several results were found. First, younger

children have a discriminative ability that shows the logical capacity

for cognitive operations exists earlier than acknowledged. This study

also reveals that young children can be equipped with certain qualities

for cognitive operations, depending on how logical the structure of the

task is. Research also shows that children develop explicit

understanding at age 5 and as a result, the child will count the sweets

to decide which has more. Finally the study found that overall quantity

conservation is not a basic characteristic of humans' native

inheritance.

Piaget's theory has been criticized for the age of appearance of a

new model of the world, such as object permanence, being dependent on

how the testing is done (see the article on object permanence).

More generally, the theory may be very difficult to test empirically

because of the difficulty of proving or disproving that a mental model

is the explanation for the results of the testing.

Neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development

expand Piaget's theory in various ways such as also considering

psychometric-like factors such as processing speed and working memory,

"hypercognitive" factors like self-monitoring, more stages, and more

consideration on how progress may vary in different domains such as

spatial or social.

Parieto-frontal integration theory of intelligence

Based on a review of 37 neuroimaging studies, Jung and Haier (2007) proposed that the biological basis of intelligence stems from how well the frontal and parietal regions of the brain communicate and exchange information with each other. Subsequent neuroimaging and lesion studies report general consensus with the theory.

A review of the neuroscience and intelligence literature concludes that

the parieto-frontal integration theory is the best available

explanation for human intelligence differences.

Investment theory

Based on the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory,

the tests of intelligence most often used in the relevant studies

include measures of fluid ability (Gf) and crystallized ability (Gc);

that differ in their trajectory of development in individuals. The 'investment theory' by Cattell states that the individual differences

observed in the procurement of skills and knowledge (Gc) are partially

attributed to the 'investment' of Gf, thus suggesting the involvement of

fluid intelligence in every aspect of the learning process.

It is essential to highlight that the investment theory suggests that

personality traits affect 'actual' ability, and not scores on an IQ test.

In association, Hebb's theory of intelligence suggested a bifurcation

as well, Intelligence A (physiological), that could be seen as a

semblance of fluid intelligence and Intelligence B (experiential), similar to crystallized intelligence.

Intelligence compensation theory (ICT)

The intelligence compensation theory (a term first coined by Wood and Englert, 2009)

states that individuals who are comparatively less intelligent work

harder, more methodically, become more resolute and thorough (more

conscientious) in order to achieve goals, to compensate for their 'lack

of intelligence' whereas more intelligent individuals do not require

traits/behaviours associated with the personality factor conscientiousness to progress as they can rely on the strength of their cognitive abilities as opposed to structure or effort.

The theory suggests the existence of a causal relationship between

intelligence and conscientiousness, such that the development of the

personality trait conscientiousness is influenced by intelligence. This

assumption is deemed plausible as it is unlikely that the reverse causal

relationship could occur; implying that the negative correlation would be higher between fluid intelligence (Gf) and conscientiousness. The justification being the timeline of development of Gf, Gc and personality, as crystallized intelligence

would not have developed completely when personality traits develop.

Subsequently, during school-going ages, more conscientious children

would be expected to gain more crystallized intelligence (knowledge)

through education, as they would be more efficient, thorough,

hard-working and dutiful.

This theory has recently been contradicted by evidence, that identifies compensatory sample selection.

Thus, attributing the previous findings to the bias in selecting

samples with individuals above a certain threshold of achievement.

Bandura's theory of self-efficacy and cognition

The

view of cognitive ability has evolved over the years, and it is no

longer viewed as a fixed property held by an individual. Instead, the

current perspective describes it as a general capacity, comprising not

only cognitive, but motivational, social and behavioural aspects as

well. These facets work together to perform numerous tasks. An essential

skill often overlooked is that of managing emotions, and aversive

experiences that can compromise one's quality of thought and activity.

The link between intelligence and success has been bridged by crediting

individual differences in self-efficacy.

Bandura's theory identifies the difference between possessing skills

and being able to apply them in challenging situations. Thus, the theory

suggests that individuals with the same level of knowledge and skill

may perform badly, averagely or excellently based on differences in

self-efficacy.

A key role of cognition is to allow for one to predict events and

in turn devise methods to deal with these events effectively. These

skills are dependent on processing of stimuli that is unclear and

ambiguous. To learn the relevant concepts, individuals must be able to

rely on the reserve of knowledge to identify, develop and execute

options. They must be able to apply the learning acquired from previous

experiences. Thus, a stable sense of self-efficacy is essential to stay

focused on tasks in the face of challenging situations.

To summarize, Bandura's theory of self-efficacy and intelligence

suggests that individuals with a relatively low sense of self-efficacy

in any field will avoid challenges. This effect is heightened when they

perceive the situations as personal threats. When failure occurs, they recover from it more slowly than others, and credit it to an insufficient aptitude.

On the other hand, persons with high levels of self-efficacy hold a task-diagnostic aim that leads to effective performance.

Process, personality, intelligence and knowledge theory (PPIK)

Predicted growth curves for Intelligence as process, crystallized intelligence, occupational knowledge and avocational knowledge based on Ackerman's PPIK Theory.

Developed by Ackerman, the PPIK (process, personality, intelligence

and knowledge) theory further develops the approach on intelligence as

proposed by Cattell, the Investment theory and Hebb, suggesting a distinction between intelligence as knowledge and intelligence as process (two concepts that are comparable and related to Gc and Gf

respectively, but broader and closer to Hebb's notions of "Intelligence

A" and "Intelligence B") and integrating these factors with elements

such as personality, motivation and interests.

Ackerman describes the difficulty of distinguishing process from

knowledge, as content cannot be entirely eliminated from any ability

test. Personality traits have not shown to be significantly correlated with the intelligence as process aspect except in the context of psychopathology. One exception to this generalization has been the finding of sex differences in cognitive abilities, specifically abilities in mathematical and spatial form.

On the other hand, the intelligence as knowledge factor has been associated with personality traits of Openness and Typical Intellectual Engagement, which also strongly correlate with verbal abilities (associated with crystallized intelligence).

Latent inhibition

It appears that Latent inhibition can influence one's creativity.

Improving

Because intelligence appears to be at least partly dependent on brain

structure and the genes shaping brain development, it has been proposed

that genetic engineering could be used to enhance the intelligence, a process sometimes called biological uplift in science fiction. Experiments on mice have demonstrated superior ability in learning and memory in various behavioral tasks.

IQ leads to greater success in education, but independently education raises IQ scores.

A 2017 meta-analysis suggests education increases IQ by 1-5 points per

year of education, or at least increases IQ test taking ability.

Attempts to raise IQ with brain training have led to increases on aspects related with the training tasks – for instance working memory – but it is yet unclear if these increases generalise to increased intelligence per se.

A 2008 research paper claimed that practicing a dual n-back task can increase fluid intelligence (Gf), as measured in several different standard tests. This finding received some attention from popular media, including an article in Wired.

However, a subsequent criticism of the paper's methodology questioned

the experiment's validity and took issue with the lack of uniformity in

the tests used to evaluate the control and test groups. For example, the progressive nature of Raven's Advanced Progressive Matrices

(APM) test may have been compromised by modifications of time

restrictions (i.e., 10 minutes were allowed to complete a normally

45-minute test).

Substances which actually or purportedly improve intelligence or other mental functions are called nootropics.

A meta analysis shows omega 3 fatty acids improves cognitive

performance among those with cognitive deficits, but not among healthy

subjects.

A meta-regression shows omega 3 fatty acids improve the moods of

patients with major depression (major depression is associated with

mental deficits). However, exercise, not just performance-enhancing drugs, enhances cognition for healthy and non healthy subjects as well.

On the philosophical front, conscious efforts to influence intelligence raise ethical issues. Neuroethics

considers the ethical, legal and social implications of neuroscience,

and deals with issues such as the difference between treating a human neurological disease and enhancing the human brain, and how wealth impacts access to neurotechnology. Neuroethical issues interact with the ethics of human genetic engineering.

Transhumanist theorists study the possibilities and consequences of developing and using techniques to enhance human abilities and aptitudes.

Eugenics is a social philosophy which advocates the improvement of human hereditary traits through various forms of intervention.

Eugenics has variously been regarded as meritorious or deplorable in

different periods of history, falling greatly into disrepute after the

defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Measuring

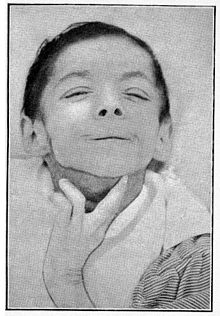

Score distribution chart for sample of 905 children tested on 1916 Stanford-Binet Test

The approach to understanding intelligence with the most supporters

and published research over the longest period of time is based on psychometric testing. It is also by far the most widely used in practical settings. Intelligence quotient (IQ) tests include the Stanford-Binet, Raven's Progressive Matrices, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale and the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children.

There are also psychometric tests that are not intended to measure

intelligence itself but some closely related construct such as

scholastic aptitude. In the United States examples include the SSAT, the SAT, the ACT, the GRE, the MCAT, the LSAT, and the GMAT.

Regardless of the method used, almost any test that requires examinees

to reason and has a wide range of question difficulty will produce

intelligence scores that are approximately normally distributed in the general population.

Intelligence tests are widely used in educational, business, and military settings because of their efficacy in predicting behavior. IQ and g

(discussed in the next section) are correlated with many important

social outcomes—individuals with low IQs are more likely to be divorced,

have a child out of marriage, be incarcerated, and need long-term

welfare support, while individuals with high IQs are associated with

more years of education, higher status jobs and higher income. Intelligence is significantly correlated with successful training and performance outcomes, and IQ/g is the single best predictor of successful job performance.

General intelligence factor or g

There are many different kinds of IQ tests using a wide variety of

test tasks. Some tests consist of a single type of task, others rely on a

broad collection of tasks with different contents (visual-spatial,

verbal, numerical) and asking for different cognitive processes (e.g.,

reasoning, memory, rapid decisions, visual comparisons, spatial imagery,

reading, and retrieval of general knowledge). The psychologist Charles Spearman early in the 20th century carried out the first formal factor analysis of correlations between various test tasks. He found a trend for all such tests to correlate positively with each other, which is called a positive manifold. Spearman found that a single common factor explained the positive correlations among tests. Spearman named it g for "general intelligence factor".

He interpreted it as the core of human intelligence that, to a larger

or smaller degree, influences success in all cognitive tasks and thereby

creates the positive manifold. This interpretation of g as a

common cause of test performance is still dominant in psychometrics.

(Although, an alternative interpretation was recently advanced by van

der Maas and colleagues. Their mutualism model

assumes that intelligence depends on several independent mechanisms,

none of which influences performance on all cognitive tests. These

mechanisms support each other so that efficient operation of one of them

makes efficient operation of the others more likely, thereby creating

the positive manifold.)

IQ tasks and tests can be ranked by how highly they load on the g factor. Tests with high g-loadings

are those that correlate highly with most other tests. One

comprehensive study investigating the correlations between a large

collection of tests and tasks has found that the Raven's Progressive Matrices have a particularly high correlation with most other tests and tasks. The Raven's

is a test of inductive reasoning with abstract visual material. It

consists of a series of problems, sorted approximately by increasing

difficulty. Each problem presents a 3 x 3 matrix of abstract designs

with one empty cell; the matrix is constructed according to a rule, and

the person must find out the rule to determine which of 8 alternatives

fits into the empty cell. Because of its high correlation with other

tests, the Raven's Progressive Matrices are generally acknowledged as a

good indicator of general intelligence. This is problematic, however,

because there are substantial gender differences on the Raven's, which are not found when g is measured directly by computing the general factor from a broad collection of tests.

General collective intelligence factor or c

A recent scientific understanding of collective intelligence, defined

as a group's general ability to perform a wide range of tasks,

expands the areas of human intelligence research applying similar

methods and concepts to groups. Definition, operationalization and

methods are similar to the psychometric approach of general individual

intelligence where an individual's performance on a given set of

cognitive tasks is used to measure intelligence indicated by the general intelligence factor g extracted via factor analysis. In the same vein, collective intelligence research aims to discover a ‘c factor’ explaining between-group differences in performance as well as structural and group compositional causes for it.

Historical psychometric theories

Several different theories of intelligence have historically been important for psychometrics. Often they emphasized more factors than a single one like in g factor.

Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory

Many of the broad, recent IQ tests have been greatly influenced by the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory.

It is argued to reflect much of what is known about intelligence from

research. A hierarchy of factors for human intelligence is used. g

is at the top. Under it there are 10 broad abilities that in turn are

subdivided into 70 narrow abilities. The broad abilities are:

- Fluid intelligence (Gf): includes the broad ability to reason, form concepts, and solve problems using unfamiliar information or novel procedures.

- Crystallized intelligence (Gc): includes the breadth and depth of a person's acquired knowledge, the ability to communicate one's knowledge, and the ability to reason using previously learned experiences or procedures.

- Quantitative reasoning (Gq): the ability to comprehend quantitative concepts and relationships and to manipulate numerical symbols.

- Reading & writing ability (Grw): includes basic reading and writing skills.

- Short-term memory (Gsm): is the ability to apprehend and hold information in immediate awareness and then use it within a few seconds.

- Long-term storage and retrieval (Glr): is the ability to store information and fluently retrieve it later in the process of thinking.

- Visual processing (Gv): is the ability to perceive, analyze, synthesize, and think with visual patterns, including the ability to store and recall visual representations.

- Auditory processing (Ga): is the ability to analyze, synthesize, and discriminate auditory stimuli, including the ability to process and discriminate speech sounds that may be presented under distorted conditions.

- Processing speed (Gs): is the ability to perform automatic cognitive tasks, particularly when measured under pressure to maintain focused attention.

- Decision/reaction time/speed (Gt): reflect the immediacy with which an individual can react to stimuli or a task (typically measured in seconds or fractions of seconds; not to be confused with Gs, which typically is measured in intervals of 2–3 minutes).

Modern tests do not necessarily measure of all of these broad

abilities. For example, Gq and Grw may be seen as measures of school

achievement and not IQ. Gt may be difficult to measure without special equipment.

g was earlier often subdivided into only Gf and Gc which

were thought to correspond to the nonverbal or performance subtests and

verbal subtests in earlier versions of the popular Wechsler IQ test.

More recent research has shown the situation to be more complex.

Controversies

While

not necessarily a dispute about the psychometric approach itself, there

are several controversies regarding the results from psychometric

research.

One criticism has been against the early research such as craniometry.

A reply has been that drawing conclusions from early intelligence

research is like condemning the auto industry by criticizing the

performance of the Model T.

Several critics, such as Stephen Jay Gould, have been critical of g, seeing it as a statistical artifact, and that IQ tests instead measure a number of unrelated abilities. The American Psychological Association's report "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" stated that IQ tests do correlate and that the view that g is a statistical artifact is a minority one.

Intelligence across cultures

Psychologists have shown that the definition of human intelligence is unique to the culture that one is studying. Robert Sternberg

is among the researchers who have discussed how one's culture affects

the person's interpretation of intelligence, and he further believes

that to define intelligence in only one way without considering

different meanings in cultural contexts may cast an investigative and

unintentionally egocentric view on the world. To negate this,

psychologists offer the following definitions of intelligence:

- Successful intelligence is the skills and knowledge needed for success in life, according to one's own definition of success, within one's sociocultural context.

- Analytical intelligence is the result of intelligence's components applied to fairly abstract but familiar kinds of problems.

- Creative intelligence is the result of intelligence's components applied to relatively novel tasks and situations.

- Practical intelligence is the result of intelligence's components applied to experience for purposes of adaption, shaping and selection.

Although typically identified by its western definition, multiple

studies support the idea that human intelligence carries different

meanings across cultures around the world. In many Eastern cultures,

intelligence is mainly related with one's social roles and

responsibilities. A Chinese conception of intelligence would define it

as the ability to empathize with and understand others — although this

is by no means the only way that intelligence is defined in China.

In several African communities, intelligence is shown similarly through a

social lens. However, rather than through social roles, as in many

Eastern cultures, it is exemplified through social responsibilities. For

example, in the language of Chi-Chewa, which is spoken by some ten

million people across central Africa,

the equivalent term for intelligence implies not only cleverness but

also the ability to take on responsibility. Furthermore, within American

culture there are a variety of interpretations of intelligence present

as well. One of the most common views on intelligence within American

societies defines it as a combination of problem-solving skills, deductive reasoning skills, and Intelligence quotient (IQ), while other American societies point out that intelligent people should have a social conscience, accept others for who they are, and be able to give advice or wisdom.