| Diabetic neuropathy | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Diabetic neuropathies are nerve damaging disorders associated with diabetes mellitus. These conditions are thought to result from a diabetic microvascular injury involving small blood vessels that supply nerves (vasa nervorum) in addition to macrovascular conditions that can accumulate in diabetic neuropathy. Relatively common conditions which may be associated with diabetic neuropathy include third, fourth, or sixth cranial nerve palsy; mononeuropathy; mononeuropathy multiplex; diabetic amyotrophy; a painful polyneuropathy; autonomic neuropathy; and thoracoabdominal neuropathy.

Signs and symptoms

Illustration depicting areas affected by diabetic neuropathy

Diabetic neuropathy affects all peripheral nerves including sensory neurons, motor neurons, but rarely affects the autonomic nervous system.

Therefore, diabetic neuropathy can affect all organs and systems, as

all are innervated. There are several distinct syndromes based on the

organ systems and members affected, but these are by no means exclusive.

A patient can have sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathy or any other

combination. Signs and symptoms

vary depending on the nerve(s) affected and may include symptoms other

than those listed. Symptoms usually develop gradually over years.

Symptoms may include the following:

- Trouble with balance

- Numbness and tingling of extremities

- Dysesthesia (abnormal sensation to a body part)

- Diarrhea

- Erectile dysfunction

- Urinary incontinence (loss of bladder control)

- Facial, mouth and eyelid drooping

- Vision changes

- Dizziness

- Muscle weakness

- Difficulty swallowing

- Speech impairment

- Fasciculation (muscle contractions)

- Anorgasmia

- Retrograde ejaculation (in males)

- Burning or electric pain

Pathogenesis

The following factors are thought to be involved in the development of diabetic neuropathy:

Microvascular disease

Vascular and neural diseases are closely related and intertwined. Blood vessels depend on normal nerve function, and nerves depend on adequate blood flow. The first pathological change in the small blood vessels is narrowing of the blood vessels.

As the disease progresses, neuronal dysfunction correlates closely with

the development of blood vessel abnormalities, such as capillary basement membrane thickening and endothelial hyperplasia, which contribute to diminished oxygen tension and hypoxia. Neuronal ischemia is a well-established characteristic of diabetic neuropathy. Blood vessel opening agents (e.g., ACE inhibitors, α1-antagonists) can lead to substantial improvements in neuronal blood flow, with corresponding improvements in nerve conduction velocities.

Thus, small blood vessel dysfunction occurs early in diabetes,

parallels the progression of neural dysfunction, and may be sufficient

to support the severity of structural, functional, and clinical changes

observed in diabetic neuropathy.

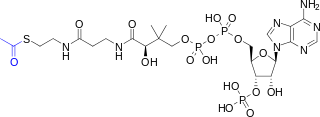

Advanced glycated end products

Elevated levels of glucose within cells cause a non-enzymatic covalent bonding with proteins,

which alters their structure and inhibits their function. Some of these

glycated proteins have been implicated in the pathology of diabetic

neuropathy and other long-term complications of diabetes.

Polyol pathway

Also called the sorbitol/aldose reductase pathway, the polyol pathway

appears to be implicated in diabetic complications, especially in

microvascular damage to the retina, kidney, and nerves.

Sensorimotor polyneuropathy

Longer

nerve fibers are affected to a greater degree than shorter ones because

nerve conduction velocity is slowed in proportion to a nerve's length.

In this syndrome, decreased sensation and loss of reflexes occurs first

in the toes on each foot, then extends upward. It is usually described

as a glove-stocking distribution of numbness, sensory loss, dysesthesia

and night time pain. The pain can feel like burning, pricking

sensation, achy or dull. A pins and needles sensation is common. Loss of

proprioception,

the sense of where a limb is in space, is affected early. These

patients cannot feel when they are stepping on a foreign body, like a

splinter, or when they are developing a callous from an ill-fitting

shoe. Consequently, they are at risk of developing ulcers and infections on the feet and legs, which can lead to amputation. Similarly, these patients can get multiple fractures of the knee, ankle or foot, and develop a Charcot joint. Loss of motor function results in dorsiflexion, contractures of the toes, loss of the interosseous muscle function that leads to contraction of the digits, so-called hammer toes.

These contractures occur not only in the foot but also in the hand

where the loss of the musculature makes the hand appear gaunt and

skeletal. The loss of muscular function is progressive.

Autonomic neuropathy

The autonomic nervous system is composed of nerves serving the heart, lungs, blood vessels, bone, adipose tissue, sweat glands, gastrointestinal system and genitourinary system. Autonomic neuropathy can affect any of these organ systems. The most commonly recognized autonomic dysfunction in diabetics is orthostatic hypotension, or becoming dizzy and possibly fainting

when standing up due to a sudden drop in blood pressure. In the case of

diabetic autonomic neuropathy, it is due to the failure of the heart

and arteries to appropriately adjust heart rate and vascular tone to

keep blood continually and fully flowing to the brain. This symptom is usually accompanied by a loss of respiratory sinus arrhythmia – the usual change in heart rate seen with normal breathing. These two findings suggest autonomic neuropathy.

GI tract manifestations include gastroparesis, nausea, bloating, and diarrhea.

Because many diabetics take oral medication for their diabetes,

absorption of these medicines is greatly affected by the delayed gastric

emptying. This can lead to hypoglycemia

when an oral diabetic agent is taken before a meal and does not get

absorbed until hours, or sometimes days later when there is normal or

low blood sugar already. Sluggish movement of the small intestine can cause bacterial overgrowth, made worse by the presence of hyperglycemia. This leads to bloating, gas and diarrhea.

Urinary symptoms include urinary frequency, urgency, incontinence and retention. Again, because of the retention of urine, urinary tract infections are frequent. Urinary retention can lead to bladder diverticula, stones, reflux nephropathy.

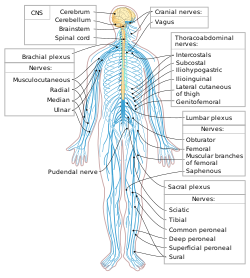

Cranial neuropathy

When cranial nerves are affected, neuropathies of the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve #3 or CNIII) are most common. The oculomotor nerve controls all the muscles that move the eye except for the lateral rectus and superior oblique muscles. It also serves to constrict the pupil

and open the eyelid. The onset of a diabetic third nerve palsy is

usually abrupt, beginning with frontal or pain around the eye and then double vision.

All the oculomotor muscles innervated by the third nerve may be

affected, but those that control pupil size are usually well-preserved

early on. This is because the parasympathetic

nerve fibers within CNIII that influence pupillary size are found on

the periphery of the nerve (in terms of a cross-sectional view), which

makes them less susceptible to ischemic damage (as they are closer to

the vascular supply). The sixth nerve, the abducens nerve,

which innervates the lateral rectus muscle of the eye (moves the eye

laterally), is also commonly affected but fourth nerve, the trochlear nerve, (innervates the superior oblique muscle, which moves the eye downward) involvement is unusual. Damage to a specific nerve of the thoracic or lumbar spinal nerves can occur and may lead to painful syndromes that mimic a heart attack, gallbladder inflammation, or appendicitis. Diabetics have a higher incidence of entrapment neuropathies, such as carpal tunnel syndrome.

Diagnosis

Diabetic

peripheral neuropathy is the most likely diagnosis for someone with

diabetes who has pain in a leg or foot, although it may also be caused

by vitamin B12 deficiency or osteoarthritis. A 2010 review in the Journal of the American Medical Association's

"Rational Clinical Examination Series" evaluated the usefulness of the

clinical examination in diagnosing diabetic peripheral neuropathy.

While the physician typically assesses the appearance of the feet,

presence of ulceration, and ankle reflexes, the most useful physical

examination findings for large fiber neuropathy are an abnormally

decreased vibration perception to a 128-Hz tuning fork (likelihood ratio

(LR) range, 16–35) or pressure sensation with a 5.07 Semmes-Weinstein

monofilament (LR range, 11–16). Normal results on vibration testing (LR

range, 0.33–0.51) or monofilament (LR range, 0.09–0.54) make large fiber

peripheral neuropathy from diabetes less likely. Combinations of signs

do not perform better than these 2 individual findings.

Nerve conduction tests may show reduced functioning of the peripheral

nerves, but seldom correlate with the severity of diabetic peripheral

neuropathy and are not appropriate as routine tests for the condition.

Classification

Diabetic neuropathy encompasses a series of different neuropathic syndromes which can be schematized in the following way:

- Focal and multifocal neuropathies:

- Mononeuropathy

- Amyotrophy, radiculopathy

- Multiple lesions "mononeuritis multiplex"

- Entrapment (e.g. median, ulnar, peroneal)

- Symmetrical neuropathies:

- Acute sensory

- Autonomic

- Distal symmetrical polyneuropathy (DSPN), the diabetic type of which is also known as diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) (most common presentation)

Prevention

Prevention is by good blood sugar control and exercise.

Treatment

Except for tight glucose control, treatments are for reducing pain and other symptoms.

Medication options for pain control include antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and capsaicin cream. About 10% of people who use capsaicin cream have a large benefit.

A systematic review concluded that "tricyclic antidepressants and traditional anticonvulsants are better for short term pain relief than newer generation anticonvulsants." A further analysis of previous studies showed that the agents carbamazepine, venlafaxine, duloxetine, and amitriptyline were more effective than placebo, but that comparative effectiveness between each agent is unclear.

The only three medications approved by the United States' Food and Drug Administration for diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) are the antidepressant duloxetine, the anticonvulsant pregabalin, and the long-acting opioid tapentadol ER. Before trying a systemic medication, some doctors recommend treating localized diabetic peripheral neuropathy with lidocaine patches.

Antiepileptic drugs

Multiple guidelines from medical organizations such as the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American Academy of Neurology, European Federation of Neurological Societies, and the National Institute of Clinical Excellence recommend AEDs, such as pregabalin, as first-line treatment for painful diabetic neuropathy. Pregabalin is supported by low-quality evidence as more effective than placebo for reducing diabetic neuropathic pain but its effect is small. Studies have reached differing conclusions about whether gabapentin relieves pain more effectively than placebo. Available evidence is insufficient to determine if zonisamide or carbamazepine are effective for diabetic neuropathy. The first metabolite of carbamazepine, known as oxcarbazepine, appears to have a small beneficial effect on pain. A 2014 systematic review and network meta-analysis concluded topiramate, valproic acid, lacosamide, and lamotrigine are ineffective for pain from diabetic peripheral neuropathy. The most common side effects associated with AED use include sleepiness, dizziness, and nausea.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

As

above, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

duloxetine and venlafaxine are recommended in multiple medical

guidelines as first or second-line therapy for DPN. A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials concluded there is moderate quality evidence that duloxetine and venlafaxine each provide a large benefit in reducing diabetic neuropathic pain. Common side effects include dizziness, nausea, and sleepiness.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

SSRIs include fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and citalopram

have been found to be no more efficacious than placebo in several

controlled trials and therefore are not recommended to treat painful

diabetic neuropathy. Side effects are rarely serious and do not cause

any permanent disabilities. They cause sedation and weight gain, which

can worsen a diabetic person's glycemic control. They can be used at

dosages that also relieve the symptoms of depression, a common comorbidity of diabetic neuropathy.

Tricyclic antidepressants

TCAs include imipramine, amitriptyline, desipramine, and nortriptyline. They are generally regarded as first or second-line treatment for DPN. Of the TCAs, imipramine has been the best studied. These medications are effective at decreasing painful symptoms but suffer from multiple side effects that are dose-dependent. One notable side effect is cardiac toxicity, which can lead to fatal abnormal heart rhythms. Additional common side effects include dry mouth, difficulty sleeping, and sedation. At low dosages used for neuropathy, toxicity is rare,

but if symptoms warrant higher doses, complications are more common.

Among the TCAs, amitriptyline is most widely used for this condition,

but desipramine and nortriptyline have fewer side effects.

Opioids

Typical opioid medications, such as oxycodone,

appear to be no more effective than placebo. In contrast, low-quality

evidence supports a moderate benefit from the use of atypical opioids

(e.g., tramadol and tapentadol), which also have SNRI properties. Opioid medications are recommended as second or third-line treatment for DPN.

Topical agents

Capsaicin

applied to the skin in a 0.075% concentration has not been found to be

more effective than placebo for treating pain associated with diabetic

neuropathy. There is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions for more

concentrated forms of capsaicin, clonidine, or lidocaine applied to the skin.

Other

Low-quality evidence supports a moderate-large beneficial effect of botulinum toxin injections. Dextromethorphan

does not appear to be effective in treating diabetic neuropathic pain.

There is insufficient evidence to draw firm conclusions for the utility

of the cannabinoids nabilone and nabiximols.

There are some in vitro studies indicating the beneficial effect of

erythropoietin on the diabetic neuropathy; however, one nerve conduction

study in mild-moderate diabetic individuals showed that erythropoietin alone or in combination with gabapentin does not have any beneficial effect on progression of diabetic neuropathy.

Medical devices

Monochromatic

infrared photo energy treatment (MIRE) has been shown to be an

effective therapy in reducing and often eliminating pain associated with

diabetic neuropathy. The studied wavelength of 890 nm is able to

penetrate into the subcutaneous tissue where it acts upon a specialized

part of the cell called the cytochrome C. The infrared light energy

prompts the cytochrome C to release nitric oxide into the cells. The

nitric oxide in turn promotes vasodilation which results in increased

blood flow that helps nourish damaged nerve cells. Once the nutrient

rich blood is able to reach the affected areas (typically the feet,

lower legs and hands) it promotes the regeneration of nerve tissues and

helps reduce inflammation thereby reducing and/or eliminating pain in

the area.

Physical therapy

Physical therapy

may help reduce dependency on pain relieving drug therapies. Certain

physiotherapy techniques can help alleviate symptoms brought on from

diabetic neuropathy such as deep pain in the feet and legs, tingling or burning sensation in extremities, muscle cramps, muscle weakness, sexual dysfunction, and diabetic foot.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and interferential current (IFC) use a painless electric current and the physiological effects from low frequency electrical stimulation to relieve stiffness, improve mobility, relieve neuropathic pain, reduce oedema, and heal resistant foot ulcers.

Gait training,

posture training, and teaching these patients the basic principles of

off-loading can help prevent and/or stabilize foot complications such as

foot ulcers. Off-loading techniques can include the use of mobility aids (e.g. crutches) or foot splints. Gait re-training would also be beneficial for individuals who have lost limbs, due to diabetic neuropathy, and now wear a prosthesis.

Exercise programs, along with manual therapy, will help to prevent muscle contractures, spasms and atrophy. These programs may include general muscle stretching to maintain muscle length and a person’s range of motion. General muscle strengthening exercises will help to maintain muscle strength and reduce muscle wasting.

Aerobic exercise such as swimming and using a stationary bicycle can

help peripheral neuropathy, but activities that place excessive pressure

on the feet (e.g. walking long distances, running) may be

contraindicated.

Heat, therapeutic ultrasound, hot wax are also useful for treating diabetic neuropathy. Pelvic floor muscle exercises can improve sexual dysfunction caused by neuropathy.

Tight glucose control

Treatment of early manifestations of sensorimotor polyneuropathy involves improving glycemic control.

Tight control of blood glucose can reverse the changes of diabetic

neuropathy, but only if the neuropathy and diabetes are recent in onset.

Conversely, painful symptoms of neuropathy in uncontrolled diabetics

tend to subside as the disease and numbness progress.

Prognosis

The

mechanisms of diabetic neuropathy are poorly understood. At present,

treatment alleviates pain and can control some associated symptoms, but

the process is generally progressive.

As a complication, there is an increased risk of injury to the feet because of loss of sensation. Small infections can progress to ulceration and this may require amputation.

Epidemiology

Globally diabetic neuropathy affects approximately 132 million people as of 2010 (1.9% of the population).

Diabetes is the leading known cause of neuropathy in developed

countries, and neuropathy is the most common complication and greatest

source of morbidity and mortality in diabetes. It is estimated that neuropathy affects 25% of people with diabetes. Diabetic neuropathy is implicated in 50–75% of nontraumatic amputations.

The main risk factor for diabetic neuropathy is hyperglycemia.

In the DCCT (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial, 1995) study,

the annual incidence of neuropathy was 2% per year but dropped to 0.56%

with intensive treatment of Type 1 diabetics. The progression of

neuropathy is dependent on the degree of glycemic control in both Type 1

and Type 2 diabetes. Duration of diabetes, age, cigarette smoking, hypertension, height, and hyperlipidemia are also risk factors for diabetic neuropathy.